Abstract

Gaucher disease, the most common lysosomal storage disease, is caused by mutations in the gene that encodes acid-β-glucosidase (GlcCerase). Type 1 is characterized by hepatosplenomegaly, and types 2 and 3 by early or chronic onset of severe neurological symptoms. No clear correlation exists between the ∼200 GlcCerase mutations and disease severity, although homozygosity for the common mutations N370S and L444P is associated with non- neuronopathic and neuronopathic disease, respectively. We report the X-ray structure of GlcCerase at 2.0 Å resolution. The catalytic domain consists of a (β/α)8 TIM barrel, as expected for a member of the glucosidase hydrolase A clan. The distance between the catalytic residues E235 and E340 is consistent with a catalytic mechanism of retention. N370 is located on the longest α-helix (helix 7), which has several other mutations of residues that point into the TIM barrel. Helix 7 is at the interface between the TIM barrel and a separate immunoglobulin-like domain on which L444 is located, suggesting an important regulatory or structural role for this non-catalytic domain. The structure provides the possibility of engineering improved GlcCerase for enzyme-replacement therapy, and for designing structure-based drugs aimed at restoring the activity of defective GlcCerase.

Introduction

Acid-β-glucosidase (GlcCerase; otherwise known as D-glucosyl-N-acylsphingosine glucohydrolase; IUBMB enzyme nomenclature number EC 3.2.1.45) is a peripheral membrane protein that hydrolyses the β-glucosyl linkage of glucosylceramide (GlcCer; Fig. 1) in lysosomes, and requires the coordinated action of saposin C and negatively-charged lipids for maximal activity (Beutler & Grabowski, 2001; Grabowski et al., 1990).

Figure 1.

Reaction catalysed by acid-β-glucosidase. Acid-β-glucosidase (GlcCerase) hydrolyses the β-glucosyl linkage of glucosylceramide (GlcCer), to yield ceramide and glucose.

On the basis of sequence similarity, GlcCerase was classified as a member of glycoside hydrolase family 30, which is a member of the glycoside hydrolase A (GH-A) clan. Inherited defects in GlcCerase result in lysosomal GlcCer accumulation and, as a consequence, Gaucher disease, the most common lysosomal storage disease (Meikle et al., 1999), which occurs at a frequency of 1 in 40,000 to 1 in 60,000 in the general population, and 1 in 500 to 1 in 1,000 among Ashkenazi Jews (Beutler & Grabowski, 2001; Charrow et al., 2000). Enzyme-replacement therapy using Cerezyme®, a recombinant human GlcCerase (Grabowski et al., 1995), is the main treatment for type 1 Gaucher disease. Although attempts at structural prediction have been made (Fabrega et al., 2000, 2002), the lack of an experimental three-dimensional structure of GlcCerase has hampered attempts to establish its catalytic mechanism and analyse the relationship between the mutations, levels of residual enzyme activity and disease severity. We now report the X-ray structure of GlcCerase at 2.0 Å resolution and discuss how the common mutations may affect enzyme activity.

Results and Discussion

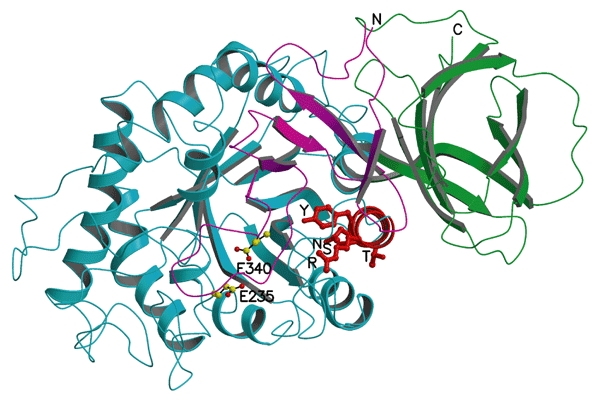

The refined X-ray structure of GlcCerase at 2.0 Å (R-factor 19.5%; R-free 23.0%) contains two GlcCerase molecules per asymmetric unit (Tables 1,2). Its overall fold comprises three domains (Fig. 2). Domain I (residues 1–27 and 383–414) consists of one main threestranded, anti-parallel β-sheet that is flanked by a perpendicular amino-terminal strand and a loop. It contains two disulphide bridges (residues 4–16 and 18–23), which may be required for correct folding (Beutler & Grabowski, 2001). Glycosylation, which is essential for catalytic activity in vivo (Berg-Fussman et al., 1993), is seen in the crystal structure at residue N19. Domain II (residues 30–75 and 431–497) consists of two closely associated βsheets that form an independent domain, which resembles an immunoglobulin (Ig) fold (Orengo et al., 1997; Westhead et al., 1999). Domain III (residues 76–381 and 416–430) is a (β/α)8 TIM barrel, which contains the catalytic site, consistent with homology to GH-A clan members (Fabrega et al., 2002; Henrissat & Bairoch, 1996). It contains three free cysteines (at positions 126, 248 and 342). Domains II and III seem to be connected by a flexible hinge, whereas domain I tightly interacts with domain III.

Table 1.

Data collection statistics

| Hg inflection | Hg peak | Hg remote | Native | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0092 | 1.0075 | 1.0015 | 0.8856 |

| Unit cell (Å) | 109.2, 286.1, 91.5 | 109.2, 286.7, 91.5 | 108.9, 284.1, 91.2 | 107.7, 285.2, 91.8 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 26–2.35 | 26–2.27 | 26–2.27 | 14.4–2.00 |

| Number of unique reflections | 58,766 | 64,819 | 64,311 | 93,248 |

| Completeness (%) 1 | 97.1 (98.3) | 96.1 (87.8) | 97.5 (99.1) | 98.4 (98.3) |

| I/σ(I) 1 | 9.6 (2.6) | 9.52 (2.1) | 9.1 (2.3) | 7.4 (1.6) |

| R sym(I) (%) 1 | 7.0 (24.7) | 7.2 (29.0) | 7.7 (29.4) | 8.4 (37.3) |

1Data for outer shell are in parentheses

Table 2.

Refinement and model statistics

| Resolution range (Å) |

14.4–2.0 |

| Number of reflections | 88,501 |

| R-factor work, free (%) | 19.5, 23.0 |

| Number of atoms: | |

| Protein (994 residues) | 7,859 |

| Hetero atoms (carbohydrate, solvent) | 1,056 |

| Average B-factors (Å2) | 28.4 |

| RMSD from ideal values: | |

| Bond length (Å) | 0.005 |

| Bond angle (°) | 1.3 |

| Dihedral angles (°) | 23.8 |

| Improper torsion angles (°) | 0.86 |

| Estimated coordinate error: | |

| Low resolution cutoff (Å) | 5.0 |

| ESD from Luzzati plot (Å) | 0.23 |

| ESD from SIGMAA (Å) | 0.32 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 3.1 |

Figure 2.

The refined X-ray structure of acid-β-glucosidase. (A) Domain I is shown in magenta and contains the two disulphide bridges, the sulphur atoms of which are shown as green balls. The glycosylation site at N19 is shown as a ball-and-stick model. Domain II, which is an immunoglobulin-like domain, is shown in green. The catalytic domain (domain III), which is a TIM barrel, is shown in blue, and the active-site residues E235 and E340 are shown as ball-and-stick models. The six most common acid-β-glucosidase (GlcCerase) mutations are shown as balls, with those that cause predisposition to severe (types 2 and 3) and mild (type 1) disease in red and yellow, respectively. (B) Two-dimensional topology of GlcCerase. The diagram is consistent with a three-dimensional view, looking down the opening of the active-site pocket, as in (A). All connecting loops in the diagram are of an arbitrary length. α-Helices and β-strands of domain III are numbered according to their position in the sequence. For clarity, sequence numbers for certain positions are shown in the connecting loops, and secondary structural elements that consist of four residues or less are not shown. NAG, N-acetylglucosamine.

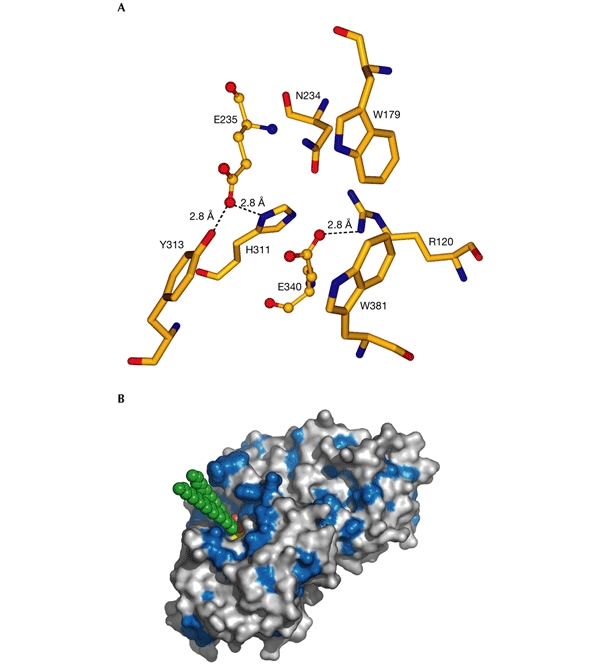

Site-directed mutagenesis and homology modelling of GlcCerase (Fabrega et al., 2000, 2002) suggest that E235 is the acid/base catalyst, and tandem mass spectrometry identified E340 as the nucleophile (Miao et al., 1994). These two residues (Fig. 3A) are located near the carboxyl termini of strands 4 and 7 (Fig. 2B) in domain III, with an average distance between their carboxyl oxygens of 5.2 Å for the two GlcCerase molecules in the structure, consistent with retention of the anomeric carbon upon cleavage, rather than inversion (Davies & Henrissat, 1995). Residues D443 and D445, which are located in the Ig-like domain (Fig. 2), cannot be directly involved in catalysis, although they seem to be covalently labelled (Dinur et al., 1986) by the irreversible GlcCerase inhibitor, conduritol-B-epoxide (Legler, 1977). Substrate docking shows that only the glucose moiety and the adjacent glycoside bond of GlcCer fit within the activesite pocket (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the two GlcCer hydrocarbon chains either remain embedded in the lipid bilayer during catalysis or interact with saposin C. In addition, an annulus of hydrophobic residues surrounds the entrance to the active site (Fig. 3B) and may facilitate interaction of GlcCerase with the lysosomal membrane or with saposin C (Wilkening et al., 1998).

Figure 3.

Active site of acid-β-glucosidase. (A) The catalytic and glucone-binding site of acid-β-glucosidase (GlcCerase). The catalytic glutamates are shown as ball-and-stick models and amino-acid residues nearby are shown as sticks. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines for those residues close enough to contact the glutamates. These residues may be involved directly in catalysis or may modulate the protonation states of the carboxyl groups. The others residues are near the docked glucosyl moiety (see (B)), and these may thus stabilize its interaction with GlcCerase. (B) Three-dimensional surface diagram of GlcCerase (created using PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org)), with a model of the docked substrate (based on the coordinates of galactosylceramide (Nyholm et al., 1990) and modified for GlcCer). Hydrophobic residues (W, F, Y, L, I, V, M and C; Hopp & Woods, 1981) are shown in blue, and the activesite residues (E235 and E340) in yellow. GlcCer is shown in CPK format (carbon atoms in green, and oxygen atoms in red).

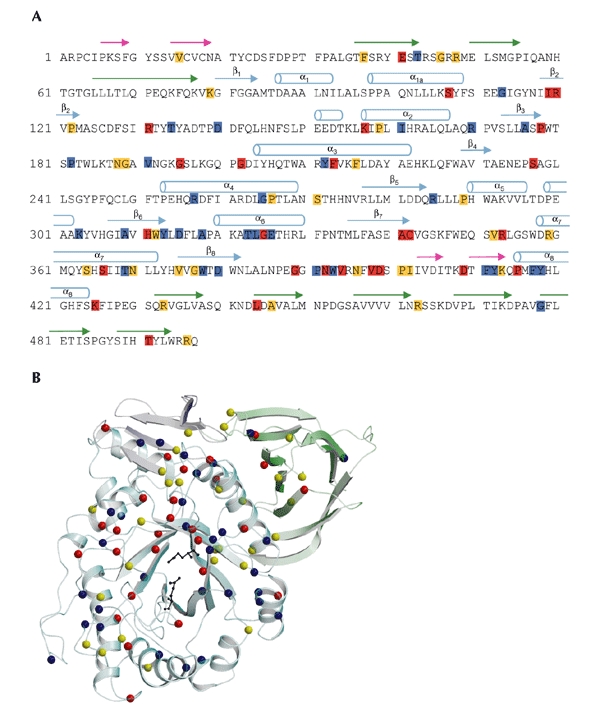

Of the ∼200 known GlcCerase mutations (Fig. 4), many are rare and restricted to a few individuals. Most mutations either partially or completely abolish catalytic activity (Meivar-Levy et al., 1994) or are thought to reduce GlcCerase stability (Grace et al., 1994). The most common mutation, N370S, accounts for 70% of mutant alleles in Ashkenazi Jews and 25% in non-Jewish patients (Table 3). N370S causes predisposition to type-1 disease and precludes neurological involvement, suggesting that it causes relatively minor changes in GlcCerase structure and, therefore, catalytic activity. Consistent with this is the localization of N370 to the longest α-helix (helix 7) in GlcCerase, which is located at the interface of domains II and III, but too far from the active site to participate directly in catalysis. Interestingly, several other mutations are found in this helix, all of which seem to point into the TIM barrel (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Mutations in acid-β-glucosidase. (A) The sequence of the 497 residues of acid-β-glucosidase (GlcCerase). Mutations reported to cause severe disease (http://www.tau.ac.il/~racheli/genedis/gaucher/gaucher.html) are shown in red, those that cause mild disease in yellow, and those for which clinical data documenting severity of the disease are lacking in blue. Only single amino-acid substitutions are included, with frameshifts and splices excluded as the enzyme is not expressed in most of these cases. Helices are indicated by cylinders, and β-strands are indicated by arrows of colours corresponding to those of the domains shown in Fig. 2. (B) Distribution in the three-dimensional structure of GlcCerase of single amino-acid substitutions that lead to Gaucher disease. Colour coding is the same as in (A). In some cases, assignment of phenotypes as mild (type 1) or severe (types 2 and 3) is based on a few individuals, and sometimes only on one. The phenotypes of several mutations are not known, as the mutations were detected in genomic DNA, and data about disease severity may not have been available. The activesite glutamate residues are shown as black sticks. Cerezyme® differs from GlcCerase by a single amino-acid substitution at residue 495 (His for Arg).

Table 3.

Most common single amino-acid substitutions in acid-β-glucosidase that cause Gaucher disease

| Mutation | Phenotype | Features | Enzyme activity | Structural features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N370S | Mild | 70% of mutant alleles in Ashkenazi Jews; invariably predisposes to mild (type 1) disease | Reduced activity; stable protein | Located on longest helix in protein (helix 7), at interface of domains II and III. Several other mutations are found on this helix (see Fig. 5) |

| V394L | Severe | – | Reduced activity; stable protein | Near aromatic residues that line one side of the active-site pocket; may disrupt this lining and, therefore, catalytic activity |

| D409H | Severe | – | Greatly reduced activity; unstable protein | Located on domain I, suggesting it is a regulatory or structural domain |

| L444P | Severe | Most common mutation that predisposes to severe (types 2 and 3) disease | Reduced activity; unstable protein | Hydrophobic core of Ig-like domain (domain II), which may lead to protein instability due to disruption of the hydrophobic core and altered folding of this domain |

| R463C | Mild | – | Reduced activity; stable protein | Located on Ig-like domain, distant from the active site |

| R496H | Mild | – | – | Located on Ig-like domain, distant from the active site |

For references about the mutations, see Beutler & Grabowski (2001). Ig, immunoglobulin.

Figure 5.

A cluster of mutations in α-helix 7 that cause Gaucher disease. Transparent ribbon diagram showing the three domains of acid-β-glucosidase as in Fig. 1A, but rotated ∼90° around the x axis to look down helix 7, which is shown in red. The amino acids on this helix that are mutated in Gaucher disease (R359, Y363, S366, T369 and N370) are shown as red balls and sticks. E235 and E340 (the activesite residues) are shown with carbon atoms as yellow balls and oxygen atoms as red balls.

Seven aromatic side chains (F128, W179, Y244, F246, Y313, W381 and F397) line one side of the active-site pocket, and may be involved in substrate recognition, as in other β-glycosidases (Chi et al., 1999; Henrissat & Bairoch, 1993). The common mutation V394L (Table 3) might perturb this lining, as the bulkier leucine side-chain could cause a conformational change in two residues of the lining, Y244 and F246. Several other mutations (H311R, A341T and C342G; Fig. 4) occur near the active site and may directly affect catalytic activity. By contrast, two relatively common mutations (Table 3), R463C and R496H, which cause predisposition to mild disease (Beutler & Grabowski, 2001), are located in the Ig-like domain, at a considerable distance from the active site (Fig. 2A). L444, which is mutated relatively frequently to proline or arginine and invariably causes predisposition to severe neuronopathic disease (Beutler & Grabowski, 2001; Erikson et al., 1997), is located in the hydrophobic core of the Ig-like domain (Fig. 2). Either of the two L444 mutations might cause a local conformational change by disrupting the hydrophobic core, resulting in altered folding of this domain (Morel et al., 1999). This is consistent with the assumption that these mutations produce unstable proteins (Grace et al., 1994). This suggests an important regulatory or structural function for domain II, perhaps in interacting with saposin C and/or acidic phospholipids. Interestingly, β-hexosaminidase and other family-20 glycosidases have a similar non-catalytic domain, the function of which is unknown (Mark et al., 2001). The structure of saposin C has recently been determined by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code ), but its coordinates have not yet been released to the public. However, the structure of its homologue, saposin B (Ahn et al., 2003), shows that the putative active form is a dimer in which a large hydrophobic cavity sequesters the acyl chains of cerebroside sulphate, and may serve to present it appropriately for hydrolysis by arysulphatase A. We cannot yet determine whether such a mechanism would explain the role of saposin C as an activator of GlcCerase, as the limited sequence homology (<14%) between saposins B and C does not allow accurate modelling of the latter. However, the Ig-like domain of GlcCerase may regulate the interaction of GlcCerase with either the lipid bilayer, saposin C or both. Finally, there are no known viable mutations in residues 14–20 of domain I and in the connecting strand (residues 1–10) and loop (residues 21–27), with the exception of the conserved mutation V15L. However, there are seven known mutations in the C-terminal strand of this domain (residues 401–414), including the common severe mutation D409H, which results in unstable protein (Beutler & Grabowski, 2001; Table 3). This suggests that domain I also has an important regulatory or structural role.

In summary, the GlcCerase structure will allow detailed and systematic analysis of the relationship between disease severity and perturbations in enzyme structure for each of the mutations (Fig. 4). It will also allow the structure-based design of small molecules that may interact with misfolded GlcCerase and stabilize the structure of some common mutations, such as N370S. The feasibility of the latter approach has recently been shown by use of a chemical chaperone to enhance GlcCerase activity in cultured cells and in in vitro assays (Sawkar et al., 2002). Such an approach, together with the mechanistic information that can now be deduced from the GlcCerase structure, paves the way for new and improved therapeutic approaches for treating Gaucher disease.

Methods

Deglycosylation, crystallization and data collection.

Cerezyme® (5 mg) was dialysed overnight against PBS (pH 7.0) and deglycosylated using N-glycosidase F (150 units; for 88 h at 25 °C). Deglycosylation was monitored by determining the reduction in molecular mass by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and mass spectrometry showed the removal of 7–14 sugar residues. Deglycosylated Cerezyme® was concentrated to 10 mg ml−1 in 1 mM MES, pH 6.6, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.02% NaN3, using a Centricon YM-10 centrifugal filter device, with a relative molecular mass cut-off of ∼10 kDa. Crystals were obtained in hanging drops at 19 °C. The drops contained 1.5 μl Cerezyme® and 1.5 μl mother liquor (1 M (NH2)2SO4, 0.17 M guanidine HCl, 0.02 M KCl, 0.1 M acetate, pH 4.6). Crystals were cryoprotected with a gradient of 5–25% glycerol. A heavy-atom derivative was obtained by soaking for three days in KHgI2 liquid (diluted 1:125,000 in mother liquor). X-ray data were collected at 100 K at three wavelengths around the Hg LIII absorption edge on beamline ID14-4, and a native data set on beamline BM14 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF). Cerezyme® crystallized in a C2221 spacegroup with two molecules in the asymmetric unit. Data were processed with MOSFLM/SCALA (Leslie, 1992) and Denzo/Scalepack (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997). See Table 1 for data collection statistics. The spacegroup and cell dimensions are similar to those recently reported for crystals of intact Cerezyme®, which diffracted, however, to significantly lower resolution (Roeber et al., 2003).

Structure determination and refinement.

Three Hg sites were located on the basis of their anomalous difference using SHELXD (Uson & Sheldrick, 1999). The Hg sites were refined and experimental phases to 2.3 Å were calculated from the multi-wavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD) data using SHARP (Fortelle & Bricogne, 1997), resulting in an overall figure of merit (FOM) of 0.403. Phases were improved by applying solvent-flipping density modification with SOLOMON (Abrahams & Leslie, 1996), resulting in an overall FOM of 0.851. An automated tracing procedure in ARP/wARP (Perrakis et al., 1999), using native amplitudes to 2.0 Å, coupled to the experimental phases, resulted in tracing of ∼95% of the two polypeptide chains. The SIGMAA map shows all 497 residues in both molecules. Final tracing was performed manually in the program O (Jones et al., 1991). Refinement of the two molecules was performed in REFMAC (Murshudov et al., 1999) and CNS (Brunger et al., 1998) at 2.0 Å, with an overall RMSD of 0.29 Å for Cα atoms between the two molecules. The maps show a single glycosylation site at N19, with one N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) on one molecule and two on the other. Nine-hundred and twenty-eight water molecules, 15 sulphate ions and 3 NAG molecules were assigned. See Table 2 for refinement and model statistics. Coordinates and structure factors for native GlcCerase were deposited in PDB (accession code ).

Acknowledgments

We thank Genzyme Israel, Ltd, for generously supplying Cerezyme®, the staff at beamlines ID14-4 and BM14 at the ESRF, and O. Yifrach for help with data collection. This work was supported by the Yeda fund of the Weizmann Institute, the Kimmelman Center for Biomolecular Structure and Assembly, and the Benoziyo Center for Neurosciences. I.S. is the Bernstein–Mason Professor of Neurochemistry, J.L.S. is the Morton and Gladys Pickman Professor of Structural Biology and A.H.F. is the Joseph Meyerhoff Professor of Biochemistry.

References

- Abrahams J.P. & Leslie A.G. (1996) Methods used in the structure determination of bovine mitochondrial F1 ATPase. Acta Crystallogr. D, 52, 30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn V.E., Faull K.F., Whitelegge J.P., Fluharty A.L. & Privé G.G. (2003) Crystal structure of saposin B reveals a dimeric shell for lipid binding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 38–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg-Fussman A., Grace M.E., Ioannou Y. & Grabowski G.A. (1993) Human acid β-glucosidase. N-glycosylation site occupancy and the effect of glycosylation on enzymatic activity. J. Biol. Chem., 268 14861–14866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler E. & Grabowski G.A. (2001) in The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease (eds Scriver, C.R., Sly, W.S., Childs, B., Beaudet, A.L., Valle, D., Kinzler, K.W. & Vogelstein, B), 3635–3668. McGraw-Hill, Inc., New York, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Brunger A.T. et al. (1998) Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr., 54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrow J. et al. (2000) The Gaucher registry: demographics and disease characteristics of 1,698 patients with Gaucher disease. Arch. Intern. Med., 160, 2835–2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Y.I., Martinez-Cruz L.A., Jancarik J., Swanson R.V., Robertson D.E. & Kim S.H. (1999) Crystal structure of the β-glycosidase from the hyperthermophile Thermosphaera aggregans: insights into its activity and thermostability. FEBS Lett., 445, 375–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies G. & Henrissat B. (1995) Structures and mechanisms of glycosyl hydrolases. Structure, 3, 853–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinur T., Osiecki K.M., Legler G., Gatt S., Desnick R.J. & Grabowski G.A. (1986) Human acid β-glucosidase: isolation and amino acid sequence of a peptide containing the catalytic site. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 83, 1660–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson A., Bembi B. & Schiffmann R. (1997) in Gaucher's Disease (ed. Zimran, A.), 711–723. Bailliere Tindall, London, UK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrega S. et al. (2000) Human glucocerebrosidase: heterologous expression of active site mutants in murine null cells. Glycobiology, 10, 1217–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrega S., Durand P., Mornon J.P. & Lehn P. (2002) The active site of human glucocerebrosidase: structural predictions and experimental validations. J. Soc. Biol., 196, 151–160. (In French.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortelle E. & Bricogne G. (1997) Heavy-atom parameter refinement for multiple isomorphous replacement and multiwavelength anomalous diffraction methods. Methods Enzymol., 276, 472–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski G.A., Gatt S. & Horowitz M. (1990) Acid β-Glucosidase: enzymology and molecular biology of Gaucher disease. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol., 25, 385–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski G.A., Barton N.W., Pastores G., Dambrosia J.M., Banerjee T.K., McKee M.A., Parker C., Schiffmann R., Hill S.C. & Brady R.O. (1995) Enzyme therapy in type 1 Gaucher disease: comparative efficacy of mannose-terminated glucocerebrosidase from natural and recombinant sources. Ann. Intern. Med., 122, 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace M.E., Newman K.M., Scheinker V., Berg-Fussman A. & Grabowski G.A. (1994) Analysis of human acid β-glucosidase by site-directed mutagenesis and heterologous expression. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 2283–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrissat B. & Bairoch A. (1993) New families in the classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem. J., 293, 781–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrissat B. & Bairoch A. (1996) Updating the sequence-based classification of glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem. J., 316, 695–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopp T.P. & Woods K.R. (1981) Prediction of protein antigenic determinants from amino acid sequences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 78, 3824–3828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T.A., Zou J.-Y., Cowan S.W. & Kjeldgaard M. (1991) Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A, 47, 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legler G. (1977) Glucosidases. Methods Enzymol., 46, 368–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie A.G.W. (1992) Recent changes to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Joint CCP4 & ESF-EAMCB Newslett. Protein Crystallogr., 26. [Google Scholar]

- Mark B.L., Vocadlo D.J., Knapp S., Triggs-Raine B.L., Withers S.G. & James M.N. (2001) Crystallographic evidence for substrate-assisted catalysis in a bacterial β-hexosaminidase. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 10330–10337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meikle P.J., Hopwood J.J., Clague A.E. & Carey W.F. (1999) Prevalence of lysosomal storage disorders. J. Am. Med. Soc., 281, 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meivar-Levy I., Horowitz M. & Futerman A.H. (1994) Analysis of glucocerebrosidase activity using N-(1-[14C]hexanoyl)-D-erythro-glucosylsphingosine demonstrates a correlation between levels of residual enzyme activity and the type of Gaucher disease. Biochem. J., 303 377–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao S., McCarter J.D., Grace M.E., Grabowski G.A., Aebersold R. & Withers S.G. (1994) Identification of Glu340 as the active-site nucleophile in human glucocerebrosidase by use of electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 10975–10978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel N., Bon S., Greenblatt H., Wodak S., Sussman J.L., Massoulié J. & Silman I. (1999) Effect of mutations in the peripheral anionic site on the stability of acetylcholinesterase. Mol. Pharmacol., 55, 982–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov G.N., Vagin A.A., Lebedev A., Wilson K.S. & Dodson E.J. (1999) Efficient anisotropic refinement of macromolecular structures using FFT. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr., 55, 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyholm P.G., Pascher I. & Sundell S. (1990) The effect of hydrogen bonds on the conformation of glycosphingolipids. Methylated and unmethylated cerebroside studied by X-ray single crystal analysis and model calculations. Chem. Phys. Lipids, 52, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orengo C.A., Michie A.D., Jones S., Jones D.T., Swindells M.B. & Thornton J.M. (1997) CATH–a hierarchic classification of protein domain structures. Structure, 5, 1093–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. & Minor W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol., 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrakis A., Morris R. & Lamzin V.S. (1999) Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nature Struct. Biol., 6, 458–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeber D., Achari A., Manavalan P., Edmunds T. & Scott D.L. (2003) Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of recombinant human acid β-glucocerebrosidase, a treatment for Gaucher's disease. Acta Crystallogr. D, 59, 343–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawkar A.R., Cheng W.C., Beutler E., Wong C.H., Balch W.E. & Kelly J.W. (2002) Chemical chaperones increase the cellular activity of N370S β-glucosidase: a therapeutic strategy for Gaucher disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 15428–15433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uson I. & Sheldrick G.M. (1999) Advances in direct methods for protein crystallography. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 9, 643–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westhead D.R., Slidel T.W.F., Flores T.P.J. & Thornton J.M. (1999) Protein structural topology: automated analysis, diagrammatic representation and database searching. Protein Sci., 8, 897–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkening G., Linke T. & Sandhoff K. (1998) Lysosomal degradation on vesicular membrane surfaces–enhanced glucosylceramide degradation by lysosomal anionic lipids and activators. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 30271–30278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]