Summary

Workshop on Chromosome Replication to Cell Division: 40 Years Anniversary of the Replicon Theory

Introduction

F. Jacob (Paris, France), co-creator of the replicon hypothesis and the operon model, opened the workshop with his memories of a summer 40 years ago. In the early morning, he and Sydney Brenner would accompany their eight children to the beach so that the ladies of the two families could sleep. As the two men talked, they illustrated their thoughts by drawing models in the sand. The issues were how the replication of DNA could be regulated and coupled to cell growth—problems that are still largely unsolved. They reasoned that, because of its extreme precision and specificity, replication could not be regulated merely by the pool of available precursors. They postulated that autonomous replication of a bacterial plasmid or a chromosome might be governed by a cis-acting sequence, the replicator, present on each DNA molecule, and a gene encoding a trans-acting initiator protein that could bind specifically to the replicator. These two elements would constitute a replication unit, the replicon, that could ensure the regulated duplication of the DNA contiguous with the replicator (Fig. 1; Jacob et al., 1963). Four decades later, the replicon model continues to provide a fruitful framework for the exploration of increasingly complex cis- and trans-acting regulatory elements, and these were a main focus of the workshop. Other topics of interest were the relationship between replication and genomic stability, and the links between the replication and segregation of daughter chromosomes. Some of the most exciting new work presented at the meeting is discussed in this report.

Figure 1.

A drawing in the sand of a replicon as presented in Jacob et al. (1963). The main circle represents the replicon, the square box represents the replicator, and the arrow indicates where the initiator protein is encoded, which, when synthesized, binds to the replicator. (Figure provided by M. Méchali.)

The EMBO workshop 'Chromosome Replication to Cell Division', organized by S.D. Ehrlich, A. Falaschi, G. Buttin, F. Cuzin, L. Jannière, M. Kohiyama, G. Pierron and J. Rouvière-Yaniv, took place in Villefranche-sur-mer, France, on 18–22 January 2003.

Initiators and more

A common theme that has emerged in prokaryotes and eukaryotes is that initiators of DNA replication act as replisome organizers to load helicase, primase and polymerase enzymes onto DNA in a stepwise manner, which leads to a correctly configured nucleoprotein complex at each origin. In eukaryotes, these initiators include the origin replication complex (ORC), Cdc6/Cdc18, Cdt1 and the six minichromosome maintenance (MCM) proteins, which all assemble on the chromatin at the end of mitosis to form the pre-replication complex (pre-RC). The subsequent activation of at least two protein kinases and the binding of the Cdc45 protein to the MCM complex are followed by DNA unwinding and the recruitment of DNA polymerases, but the mechanisms regulating this pathway are still unknown. S. Kearsey (Oxford, UK) provided new insight by using fluorescently labelled proteins to show that the essential MCM10 protein is not required to load the MCM2–7 complex in fission yeast but rather at the later step of Cdc45 loading. In addition, H. Takisawa (Osaka, Japan) reported that his group has identified five other novel proteins required for Cdc45 loading in Xenopus using in vitro assays.

A general problem for the cell is how to ensure that all chromosome segments are replicated once per cell cycle, but not twice. Eukaryotic origins are normally 'licensed' for initiation as the cells exit mitosis. In budding yeast, the frequency of licensing is limited by cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity. These enzymes phosphorylate some of the MCM proteins, which are prime candidates for supplying DNA helicase activity at the replication fork. J. Diffley (London, UK), showed that phosphorylated MCM components cannot be loaded into pre-RCs and, in addition, the phosphorylated forms are exported from the nucleus. However, inhibition of cyclin activity to reduce CDK activity in the G2 phase allows the formation of pre-RCs and, subsequently, untimely initiation of DNA replication. A large fraction of cancer cells have deregulated cyclin levels, which might cause aberrant DNA replication and contribute to chromosome instability. Overproduction of the initiator protein CDT1 in human cells can lead to genomic instability due to the re-replication of some regions (A. Dutta, Boston, MA, USA). These regions are replicated first in a normal S phase. Overreplication can be inhibited by geminin, which is a known inhibitor of DNA replication in higher eukaryotes, and only occurs in cells that lack p53, a protein known as the 'guardian of the genome'. Presumably, the mechanism that prevents multiple rounds of replication operates through DNA-damage-sensing pathways that activate p53 and lead to induction of the Cdk2 inhibitor p21.

In bacteria, DnaA is the initiator protein, which is able to initiate replication only when ATP is bound. A process called RIDA (regulatory inactivation of DnaA) stimulates the hydrolysis of DnaA–ATP, and this leads to its inactivation (T. Katayama, Kyushu, Japan). RIDA involves the replicative polymerase (Pol III), its sliding clamp (β), and a recently discovered factor called Hda (homologous to DnaA; Kato & Katayama, 2001). New data presented by W. Firshein (Middletown, CT, USA) show that Hda is associated with the membrane and also interacts with the RK2 plasmid initiator, TrfA. This controlled inactivation of DnaA ensures that initiation is coupled to polymerase loading and elongation at the replication fork. As the replication fork progresses, the active DnaA is converted to the inactive form.

Although there is little data to support the membrane attachment of nascent DNA that was originally postulated as part of the replicon model, DNA–membrane interactions are certainly involved in regulating DNA replication. M. Salas (Madrid, Spain) showed that the replication proteins p1 and p16.7 of the Bacillus subtilis phage φ29 are located at the host membrane. Protein p1 assembles in multimeric structures that associate with the membrane and probably provide an anchor for the terminal protein (TP) and the rest of the replication machinery. Protein p16.7 is an integral membrane protein that forms multimers of dimers and interacts with both single-stranded (ss)DNA and TP, which suggests that p16.7 links TP and the newly synthesized ssDNA with the membrane.

Replicators: flexible and elusive

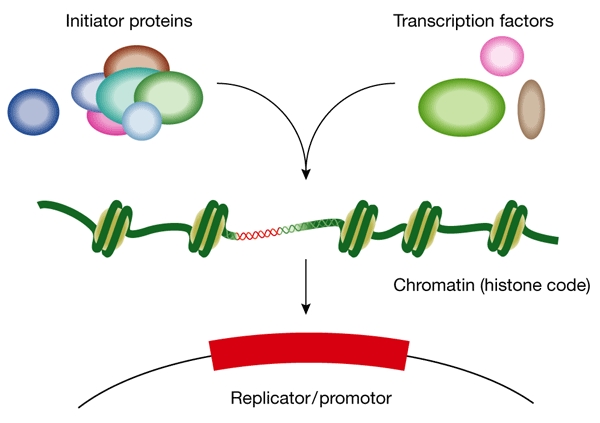

The regulation of replicator usage in eukaryotes and the timing of firing are influenced by the developmental stage of the organism, the differentiation state of the cell, gene expression, DNA damage and the perturbation of replication fork progression (Fig. 2). The existence of metazoan replicator elements that are analogous to those of prokaryotes has remained controversial and, even in yeast, the requirement for replicators is being questioned. C. Newlon (Newark, NJ, USA) has constructed a budding yeast chromosome that lacks all known replicators but is nevertheless maintained as a stable chromosome. Her data show that the ends of the chromosome have a crucial role in chromosome maintenance and indicate the existence of a novel replication mechanism. T. Kelly (New York, NY, USA) presented evidence indicating that the ORC initiator proteins can bind to any intergenic fission yeast DNA sequence with a sufficiently AT-rich region and that many such sequences function as replicator elements in yeast plasmids. Moreover, Xenopus egg extracts reconstituted with human ORC were shown to assemble functional pre-replication complexes with equal efficiency on bacterial vector DNA and on metazoan DNA thought to contain an origin on the basis of biochemical evidence. M. DePamphilis (Bethesda, MD, USA) showed that Orc4 from fission yeast competes with Xenopus ORC for chromatin binding, thereby inhibiting DNA replication in the egg extract. By contrast, Orc4 that lacks the AT-rich DNA-binding domain does not affect ORC binding or replication activity. Kelly speculated that the genomes of prokaryotes and budding yeast, which are densely packed with genes, might have evolved to rely on specific intergenic DNA sequences to act as replicators, whereas the huge intergenic regions of metazoan genomes offer these species more flexibility and might make the presence of replicators unnecessary.

Figure 2.

Initiation of DNA replication in eukaryotes is regulated by the presence of initiator proteins and transcription factors and depends on nucleosome localization. (Figure provided by A. Altman.)

However, genetic evidence was also presented for the existence of replicators in metazoan genomes: when certain metazoan DNA fragments that contain a replication start site are placed at ectopic chromosomal sites, they are sufficient to direct local initiation of replication. M. Aladjem (Bethesda, MD, USA) identified two independent replicators from an 8-kb segment of the human β-globin locus that direct initiation when placed at an ectopic chromosomal site in monkey cells. The same defined parts of the segment were essential for activity at both the ectopic site and in the β-globin locus. A. Falaschi (Trieste, Italy) presented new data showing that a 1.2-kb segment containing the human lamin B2 start site functions as a replicator in ectopic chromosomal sites. A novel laser-crosslinking method combined with biochemical approaches revealed that Orc2 and other pre-replication proteins reside near the start site of replication in G1 phase, but that Orc2 shifts to a new position in S phase. G. Wahl (La Jolla, CA) reported that a sequence of only 109 bp from the origin-β start site at the hamster dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) locus was sufficient to direct initiation when placed in an ectopic chromosomal site, and its deletion from the endogenous locus reduced local initiation. E. Fanning (Nashville, TN, USA) discussed a distal AT-rich element in the ectopic DHFR origin-β that, when deleted, almost completely abolished both initiation activity and ORC binding near the start site. Replacement of this element by a human ORC binding site restored both ORC binding and replicator activity.

Semi-conservative DNA replication was first shown by the classical experiment of Meselson and Stahl, in which bacteria were grown in medium containing heavy nitrogen to density-label the DNA, then were transferred to medium with light nitrogen. The newly replicated DNA was shown to have a hybrid density (Meselson & Stahl, 1958). By using a densityshift technique to select newly replicated DNA and then hybridizing these molecules to genomic microarrays, B. Brewer (Seattle, WA, USA) has developed a powerful method to study the timing of activation of replication origins in vivo in the whole yeast genome. Several factors that affect origin firing in budding yeast, such as the Ku protein, the Clb5 cyclin and histone acetylation were identified, and the method holds promise for identifying further factors that regulate initiation from individual start sites. Furthermore, this method can also be used to measure the rate of replication fork movement in any chromosomal region.

When replication forks are challenged

Replication forks do not always progress at the same rate from an origin of replication through an entire replicon, but might stall or break down when they encounter damage in the template DNA or when there is a limited supply of deoxyribonucleotide precursors. These events normally activate checkpoint signalling and cell-cycle delay, and promote genetic instability if left unchecked. P. Plevani (Milan, Italy) described a dominant mutation of primase that prevents checkpoint activation by stalled forks in S phase, which raises questions about the nature of the signal that activates checkpoint kinases. He also reported a mutant that fails to activate the Rad53 checkpoint kinase, specifically after ultraviolet (UV) irradiation. The mutation affected Rad14, a component of the nucleotide-excision-repair pathway, indicating that this pathway has an active role in sensing UV damage that activates the checkpoint, as well as in its subsequent repair.

E. Schwob (Montpellier, France) reported that premature activation of S phase in yeast cells that lack the CDK-inhibitor Sic1 caused an increase in inter-origin spacing, due to fewer origins firing, and to fewer replication forks compared with wild-type cells. The lack of Sic1 also led to a marked increase in the incidence of double-stranded breaks, which gave rise to genetic instability in the mutant cells. E. Boye (Oslo, Norway) found that UV irradiation of fission yeast cells in G1 phase inhibited the formation of pre-RCs, and initiation of replication from early replicators was delayed. Surprisingly, this delay was not dependent on known checkpoint proteins or on phosphorylation of the CDK Cdc2, which is the target of the other DNA damage checkpoints in fission yeast. A delay in the synthesis of proteins that are required for pre-RC formation was reported, indicating that translation could be involved in this novel mechanism.

Analysis of pulse-labelled replicating DNA by molecular combing and fluorescence in situ hybridization now allows the determination of origin usage and replication fork progression at specific sites in single DNA fibres from mammalian cells. M. Debatisse (Paris, France) used this approach to show that one dominant origin in a cluster of mammalian origins was usually activated in every cell cycle. However, cells exposed to unbalanced nucleotide pools responded by decreasing the rate of fork progression and activation of the dominant origin, and by increasing the use of normally dormant origins. P. Pasero (Montpellier, France) also applied molecular combing to show that the loss of the Sgs1 helicase, an enzyme thought to participate in the repair of stalled forks in budding yeast, causes the rate of replication fork progression to increase, and might explain the enhanced genetic instability found in sgs1 mutants.

Chromatin rules

Several speakers presented promising strategies for exploring the effect of chromatin modification and transcriptional-control elements on origin selection and replication timing. M. Aladjem showed that insertion of a selectable transgene into a heterochromatic, and therefore normally late-replicating, region in mouse cells caused the region to replicate early in S phase. However, transcription might not correlate with the control of replication, as a silent transgene carrying the β-globin locus control region but no promoter also induced the late-replicating region to replicate early. The early timing of replication correlated with histone H3 and H4 acetylation of the transgene rather than with its transcription.

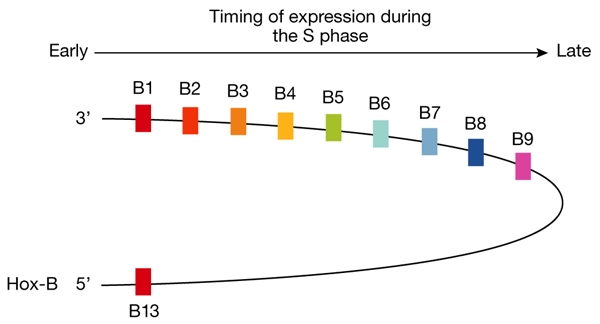

In early Xenopus development, replication can begin at any DNA sequence, but at the mid-blastula transition, the nucleus is reorganized into transcriptionally programmed chromatin domains that greatly restrict the number of replication start sites (Méchali, 2001). M. Méchali (Montpellier, France) described an intriguing correlation between the expression of the ten genes in the large Hox-B domain (B1–B9 and B13; Fig. 3) and their replication. After the mid-blastula transition, the temporal sequence of gene transcription in the domain is the same as their timing of replication, starting with the B1 gene at the 3′ end and continuing through to the B9 gene at the 5′ end of the transcription unit. Furthermore, when replication fork progression was inhibited, transcription of the B1 and B13 genes was maintained, whereas expression of the intervening genes was reduced, as if their expression depended on replication fork progression through the domain. By contrast, expression of the B1 and B13 genes seemed to depend on the passage of the cell through mitosis. These data suggest that the Hox-B genes might reside in a 'chromo-replicon' with the B1 and B13 genes near the base of a chromatin loop (Fig. 3). Méchali postulated that this represents a metazoan replicon that is linked to developmentally regulated gene expression through epigenetic modifications.

Figure 3.

Timing of expression of the Hox-B genes correlates with genomic position and with the timing of replication of the individual genes. (Figure provided by M. Méchali.)

Replicating and delivering chromosomes

During the past 40 years, the insightful suggestion that “what is moving during replication might not be the enzyme system along the DNA, but rather the DNA through the enzyme system” (Jacob et al., 1963), has been validated by accumulating evidence for a 'factory' model of replication (Lemon & Grossman, 1998; Sawitzke & Austin, 2001). This model acts as a framework for current studies that aim to link replication to cell division, and these comprised some of the most exciting presentations at the workshop.

In his keynote lecture, B. Stillman (Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA) noted that some eukaryotic initiator proteins link replication with cytokinesis (Bell, 2002; Pflumm, 2002). The human ORC6 subunit, for example, is essential for DNA replication in human cells, but at mitosis it appears in reticular structures at the cell periphery and also colocalizes with proteins of the outer kinetochore. However, during cytokinesis, ORC6 is localized in the Fleming body, the narrow connection that forms between dividing cells, and small-interfering-RNA-mediated silencing of ORC6 causes aberrant replication and cell division. Furthermore, ORC2 silencing leads to aberrant condensation and segregation of chromosomes, indicating that these proteins have several roles, and might link the pathways of replication, segregation and cytokinesis.

A thought-provoking model of how DNA replication and cell division could be coordinated was presented by N. Kleckner (Cambridge, MA, USA). The model, which could apply to all organisms, involves a mechanism of cell-cycle control that is dependent on chromosome structure and is based on several findings, such as: replication forks move more slowly when chromosome structure has been perturbed; more time is spent in meiosis compared with mitosis, presumably caused by extensive recombination in meiosis; and the inhibition of replication fork progression in Escherichia coli inhibits the initiation of replication. Kleckner suggested that the origins are licensed to initiate by the parting of the sister chromosomes. Such a control mechanism would explain the precise synchrony of initiation observed at E. coli chromosomal origins.

K. Nasmyth (Vienna, Austria) presented new data in support of a model in which yeast cohesin 'embraces' sister chromatids during metaphase (Haering et al., 2002). In this model, the two head domains of the Smc1/Smc3 dimer of cohesin are clasped together by specific contacts with the carboxy- and amino-terminal domains of another cohesin subunit, Scc1, and this ring encircles the two sister chromatids. Scc1 cleavage by the Esp1 protease releases the chromatids, and this event is required for the transition from metaphase to anaphase. A fascinating parallel with the prokaryotic world is represented by the ScpA protein of B. subtilis. ScpA interacts with proteins of the structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) family and forms a complex that might encircle two segments of the same chromosome, holding them together at the base of a loop to mediate their compaction (P. Graumann, Marburg, Germany).

To explore the dynamics of replication and segregation in bacteria, D. Sherratt (Oxford, UK) tagged the E. coli replication factory, the origin and the terminus with different fluorochromes, which allowed their positions to be visualized in real-time by video microscopy. Rapidly growing cells initiated at two origins per cell. Newly replicated origins separated soon after replication, initially remaining close together and later migrating away from each other along the longitudinal axis of the cell. In the dividing cell, with four origins, a single terminus was asymmetrically positioned in one incipient daughter. As the cell divided, two termini were visualized, and one of them rapidly moved through the septum into the sister cell. This process is facilitated by the FtsK protein, which interacts with the terminus and 'pumps' the DNA through the closing septum. The data indicate that a translocase activity of FtsK can impose directionality in vivo and convert catenanes to unknotted dimers that are then resolved to free monomers, allowing chromosome separation.

The mechanism of bacterial chromosome segregation and the question over the existence of bacterial sister chromosome cohesion were the subjects of a spirited debate. S. Hiraga (Kumamoto, Japan), a pioneer in the field of bacterial chromosome segregation, showed that newly replicated origins, as well as other regions of the chromosome, colocalize for most of the cell cycle, probably through sister cohesion. This interpretation was supported by data from Kleckner's group, whereas Sherratt and S. Austin (Frederick, MD, USA) found no evidence of cohesion. In addition, L. Shapiro (Stanford, CA, USA) reported that in Caulobacter the origins were physically separated immediately after initiation.

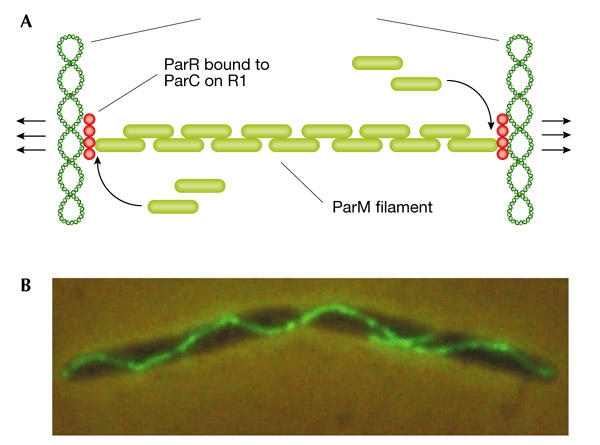

K. Gerdes (Odense, Denmark) presented evidence that prokaryotes can assemble cytoskeletal structures. The ParM protein, encoded by the E. coli plasmid R1, forms actin-like filaments that ensure correct partitioning of daughter plasmids. ParR protein that is bound to a centromere-like parC site interacts with ParM and seems to nucleate ParM polymerization. Sister plasmid parC regions are initially paired by ParR in the middle of the cell. The continuous insertion of ParM monomers at the ParR ends of a filament provides a means of 'pushing' the two sister molecules towards opposite poles (Fig. 4). The ATP form of ParM is required for filament assembly; ATP hydrolysis takes place within the filament and is required for depolymerization.

Figure 4.

The actin-like ParM protein ensures correct partitioning of R1 plasmids in Escherichia coli. (A) Insertion of new ParM monomers (green bricks) occurs at the interface with ParR (red circles), which is bound to the R1 parC sites. This insertion pushes the R1 plasmids apart. (B) Elongated E. coli cell contaning fluorescent ParM filaments. (Figure provided by K. Gerdes.)

How can cells divide exactly in the middle?

In E. coli, the MinC, MinD and MinE proteins direct the formation of the contractile FtsZ ring in the middle of the cell. The MinD protein binds to the inner membrane of one half of the cell and then oscillates between the two halves. MinE binds to the edge of the MinD-covered area, at mid-cell, and 'chases' the edge of the MinD-covered area from the centre of the cell, first towards one pole, and then towards the other. Therefore, MinE excludes MinD from the middle of the cell. MinC inhibits FtsZ-ring formation and, through its binding to MinD, is positioned mainly at the poles by the MinDE oscillator. Consequently, the only place where an FtsZ ring can form is in the middle of the cell. P. de Boer (Cleveland, OH, USA) presented a movie of a computer simulation, based on pattern formation theory, of how MinE chases MinD towards one of the poles. The molecular basis for the oscillator seems to be that ATP-bound MinD dimerizes and has a high affinity for the membrane, whereas ADP–MinD is a cytoplasmic monomer. MinE causes the hydrolysis of MinD-bound ATP, which results in the release of MinD from the membrane. J. Lutkenhaus, (Kansas City, KS, USA) showed that the MinD ATPase was stimulated both by MinE and phospholipids, which might explain why MinE is preferentially situated at the rim of the MinD area.

Perspectives

The meeting represented an unusual merger of ideas from the prokaryotic and eukaryotic worlds. Initiation mechanisms and initiators seem to be more similar than previously thought and even the process of segregation might have common themes in different organisms. The congenial atmosphere of the workshop, the stimulating conversations and environment, and the exciting presentations should inspire the participants to draw new circles in the sand in pursuit of the mechanisms of chromosome duplication and transmission.

Acknowledgments

The meeting was sponsored by EMBO with financial support from the Pasteur Institute, Centre National de la Récherche Scientifique, Societé Francaise de Biochemie et Biologie Moléculaire, and Institut National de la Récherche Agronomique. We thank the speakers for permission to cite their work and apologize to those whose work was omitted due to space constraints. The authors are supported by the Norwegian Cancer Society and the Norwegian Research Council (K.S. and E.B.), the European Union (K.S.), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences/National Institutes of Health and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, USA (E.F.).

References

- Bell S.P. (2002) The origin recognition complex: from simple origins to complex functions. Genes Dev., 16, 659–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob F., Brenner S. & Cuzin F. (1963) On the regulation of DNA replication in bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol., 28, 329–348. [Google Scholar]

- Haering C.H., Lowe J., Hochwagen A. & Nasmyth K. (2002) Molecular architecture of SMC proteins and the yeast cohesion complex. Mol. Cell, 9, 773–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato J. & Katayama T. (2001) Hda, a novel DnaA-related protein, regulates the replication cycle in Escherichia coli. EMBO J., 20, 4253–4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon K.P. & Grossman A.D. (1998) Localization of bacterial DNA polymerase: evidence for a factory model of replication. Science, 282, 1516–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Méchali M. (2001) DNA replication origins: from sequence specificity to epigenetics. Nature Rev. Genet., 2, 640–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meselson M. & Stahl F. (1958) The replication of DNA in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 44, 671–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflumm M.F. (2002) The role of DNA replication in chromosome condensation. BioEssays, 24, 411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawitzke J. & Austin S. (2001) An analysis of the factory model for chromosome replication and segregation in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol., 40, 786–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]