Abstract

The Drosophila melanogaster gene Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Alk) is homologous to mammalian Alk, which encodes a member of the Alk/Ltk family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). In humans, the t(2;5) translocation, which involves the ALK locus, produces an active form of ALK, which is the causative agent in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The physiological function of the Alk RTK, however, is unknown. In this paper, we describe loss-of-function mutants in the Drosophila Alk gene that cause a complete failure of the development of the gut. We propose that the main function of Drosophila Alk during early embryogenesis is in visceral mesoderm development.

Introduction

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Alk) encodes a novel receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK), which was first described in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in humans (Fujimoto et al., 1996; Morris et al., 1994). ALK has since been shown to be involved in many other translocations in anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL), as well as in other cancers, such as inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours (IMTs; Duyster et al., 2001; Falini, 2001). Despite the identification of the mouse Alk RTK in 1997 (Iwahara et al., 1997; Morris et al., 1997), the function of Alk in vivo has remained elusive. This is also true of leukocyte tyrosine kinase (Ltk) RTK, the related Alk/Ltk family member in mice and humans. Recently, we identified an Alk relative in Drosophila (Loren et al., 2001), which seems to encode just one member of the Alk/Ltk RTK family in its genome. The molecular similarity between Drosophila Alk and mammalian Alks suggests that mutants of Alk in flies may affect similar processes. In this paper, we report that the Drosophila Alk RTK has a crucial function in gut development in vivo.

Results and Discussion

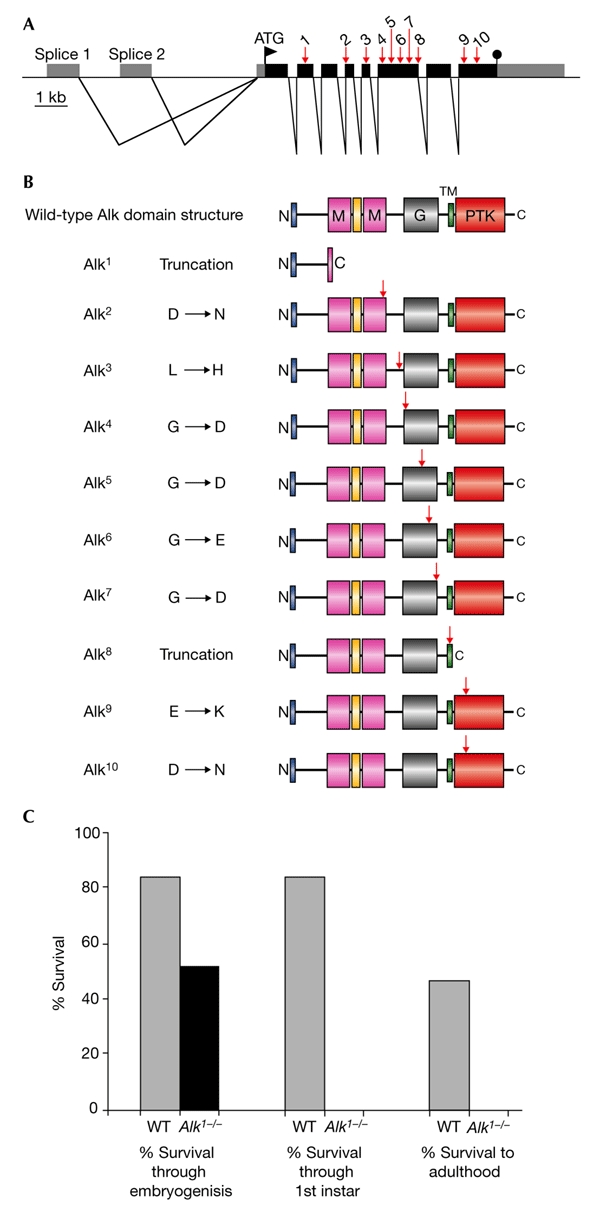

We were initially interested in the physiological function of the Alk RTK. To investigate this, we set out to mutate the Alk locus in Drosophila, first by creation of a designer deletion over the Alk53 locus (for details, see supplementary information online), which was subsequently used in an ethylmethane sulphonate (EMS) screen with the aim of identifying Alk mutant animals. Eleven independent Alk mutants were identified using this approach, and each showed similar phenotypes, as described below. The Alk mutations (Alk1 to Alk10 ) and their associated molecular characteristics are shown in Fig. 1. Significantly, all the mutations identified were located in amino acids that are conserved between Drosophila, mouse and human Alk. The Alk11 mutant line carried several amino-acid mutations and will not be discussed further.

Figure 1.

Molecular organization of the Drosophila Anaplastic lymphoma kinase locus and characterization of mutant alleles. (A) Schematic representation of the genomic structure of the Drosophila Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Alk) locus at 53C showing the intron–exon structure and open reading frame. Black and grey boxes represent coding and non-coding sequences, respectively. The locations of ethylmethane sulphonate (EMS) mutations in Alk (Alk1 to Alk10 ) are indicated by arrows. (B) Schematic representation of domain alterations in Alk alleles. The wild-type Alk domain structure is shown at the top, including the MAM (named after mephrins, A-5 protein and receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase mu) domains (M), the glycine-rich domain (G), the transmembrane domain (TM) and the protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) domains. The locations of EMS mutations in Alk are indicated by arrows. (C) Effect of the Alk 1 mutation on viability.

The Drosophila Alk mutants are highly informative about Alk RTK function. The mutations can be divided into three groups: truncations (Alk1 and Alk8 ), point mutations within the extracellular domain (Alk2 to Alk7 ) and point mutations within the protein tyrosine-kinase (PTK) domain (Alk9 and Alk10 ). Alk1 is a mutation of Gln 306 at the beginning of the first MAM (named after mephrins, A-5 protein and receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase mu) domain, which creates a stop codon and results in a truncated protein. This protein is estimated to have a molecular weight of ∼33 kDa and, consistent with this, analyses of heterozygous Alk1 mutant animals showed the presence of a truncated protein (see supplementary information online). The Alk1 protein lacks any recognizable domain, and we consider this allele to be an Alk RTK functional null. The second mutation that causes a truncation, Alk8 , arises from a splice-donor-site mutation and is predicted to generate a truncation just after the transmembrane domain. As no Alk mutant phenotypes are seen in Alk8 heterozygous animals, it seems that the mutant protein expressed does not act in the predicted dominant-negative manner, at least when expressed at endogenous levels. Interesting conclusions about the functional importance of the various Alk extracellular regions can be made from the Alk point mutations that lie within the extracellular domain.

Alk is the only RTK that contains a MAM domain in its extracellular region (Loren et al., 2001). MAM domains are comprised of ∼160 amino acids, and are present in transmembrane proteins such as the meprins and receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatases, in which they seem to function in cell–cell interactions (Beckmann & Bork, 1993; Jiang et al., 1993). In Drosophila Alk, the second MAM domain seems to be important, as Alk2 was identified as a mutation of Asp 681 in this domain. More surprisingly, the Drosophila Alk mutant screen underscores the importance of the glycine-rich region, a region that contains stretches of up to six glycines in a row, which the Alk RTK shares with its relative, Ltk. In Alk4 , Alk5 , Alk6 and Alk7 mutants, a single glycine within the glycine-rich domain is mutated to an acidic amino acid. All of the glycines that are mutated in the Drosophila Alk mutants are conserved not only between the Drosophila and human Alks, but also in the Ltk RTK, thus suggesting an important role for this domain and highlighting the intolerance of an acidic residue in the stretches of glycine in this domain.

The third class of Alk mutants have point mutations in the intracellular domain. It is interesting to note that no mutations were found in the six potential phosphotyrosine motifs that lie outside the PTK domain, and although this may simply be due to chance, it may also indicate some plasticity in the signalling pathways downstream of the Drosophila Alk receptor. Both Alk9 and Alk10 have mutations that lie in the conserved PTK catalytic domain of the receptor, thus indicating that in the case of Drosophila Alk, the PTK activity of the receptor is indeed essential for its in vivo action. This is an important observation, as PTK activity is not essential for at least one RTK in Drosophila (Yoshikawa et al., 2001). Alk9 is a mutation in the conserved sub-domain III of the kinase domain, in which the invariant glutamate (Glu 1244 in Drosophila Alk) in the C-helix, which is responsible for stabilizing the catalytic lysine and the α- and β-phosphates of Mg-ATP, is mutated to lysine. Last, Alk10 has a mutation of the aspartic acid (Asp 1347 in Drosophila Alk) of the highly conserved triplet Asp-Phe-Gly (DFG), in subdomain VII, to asparagine. This aspartic acid is an invariant residue in protein kinases and is essential for activity, functioning to orientate the γ-phosphate of Mg-ATP for transfer to the substrate. Thus, from the ten Alk mutant alleles we have identified, we can infer the importance of the different domains in the Drosophila Alk RTK: functionally, the second MAM domain, the glycine-rich domain and the PTK domain are of crucial importance for Drosophila Alk function.

Fifty per cent of animals homozygous for Alk mutations died as embryos, and the rest died as first-instar larvae (Fig. 1C). In no case did an Alk mutant animal survive past the first-instar larval stage. Despite expression of Alk in the brain in mice and flies (Iwahara et al., 1997; Loren et al., 2001; Morris et al., 1997), the central nervous system of mutant larvae seems to be generally normal, as visualized by staining with monoclonal antibody 22C10 (data not shown). Both human and Drosophila Alk have been reported to be expressed in the gut (Loren et al., 2001; Morris et al., 1994), with Drosophila Alk being highly expressed in the developing visceral mesoderm during embryogenesis (Loren et al., 2001).

Visceral muscles are important components of many internal organ systems, particularly the gastrointestinal and urogenital tracts, respiratory tract and vascular system. In Drosophila, the visceral musculature is less diverse and primarily consists of the musculature of the digestive tract. Following the early subdivision of the mesoderm in the embryo, cells are specified to contribute to distinct tissues, which then perform coordinated migrations to form organs. The Drosophila visceral mesoderm is composed of two sets of muscles, an inner layer of circular muscles derived from cells along the trunk of the embryo, and an outer layer of longitudinal muscles derived from the posterior end of the embryo (Campos-Ortega & Hartenstein, 1997). The presumptive visceral mesoderm can first be identified as 12 metameric clusters. The cells of these clusters migrate longitudinally to form two parallel bands along most of the length of the embryo, then ventrally and dorsally to form a closed tube, which is lined by endoderm (Nguyen & Xu, 1998). Longitudinal visceral-muscle precursors migrate over the circular muscle cells.

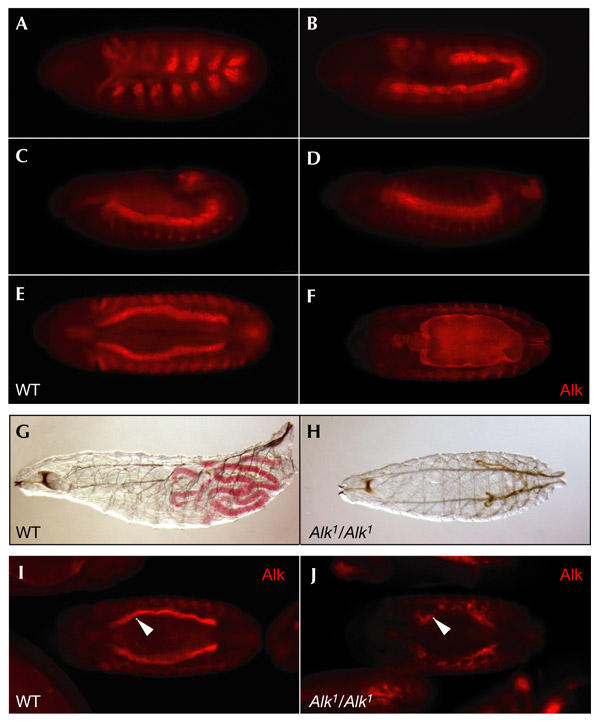

Using immunohistochemistry, we examined the expression of Alk protein in the developing visceral mesoderm in detail (Fig. 2A–F). Alk expression is first detected at germband extension (stage 10) as two Alk-positive cell groups per segment in the metameric clusters that correspond to presumptive visceral mesoderm (Fig. 2A). During germband retraction (stage 11), the clusters on each side of the embryo fuse into a continuous band (Fig. 2B). At the end of germband retraction (stage 13), Alk is expressed in a broad band of visceral mesoderm on each side of the embryo (Fig. 2C,D). During stage 14, these two bilateral bands begin their expansion (Fig. 2E). By late embryogenesis, the cells of the visceral mesoderm have spread out dorsally and ventrally to encircle the entire gut (Fig. 2F). Alk mutant animals that survived to first-instar stages were analysed using a gut-coloration assay. Whereas heterozygous sibling animals were robust, with healthy appetites (Fig. 2G), Alk mutant animals did not seem to ingest food (Fig. 2, compare G and H). On fine dissection, these animals were found to lack discernable intestinal structures (data not shown). Further analysis of the developing gut in Alk mutant animals showed that the Alk-positive visceral mesoderm was severely disrupted and that no functional midgut was formed (Fig. 2, compare I and J).

Figure 2.

A role for Drosophila Anaplastic lymphoma kinase during gut development. (A–F) In wild-type (WT) embryos Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Alk) protein is expressed throughout visceral mesoderm development, as visualized by anti-Alk polyclonal antibodies. (A) Stage 10, lateral view. (B) Stage 11, lateral view. (C) Stage 12, lateral view. (D) Stage 13, lateral view. (E) Stage 14, ventral view. (F) Stage 15, ventral view. (G,H) Alk mutants are unable to eat. (G) Heterozygous sibling first-instar larva. (H) Alk1 mutant first-instar larva. Alk mutants were identified by the absence of Kruppel–GFP (green fluorescent protein). (I,J) Alk mutants show severe visceral mesoderm defects. (I) Heterozygous sibling embryo, stage 15, ventral view. (J) Alk1 mutant embryo, stage 15, ventral view. Alk mutant embryos were identified by the absence of a lacZ balancer. Embryos are orientated with the anterior to the left.

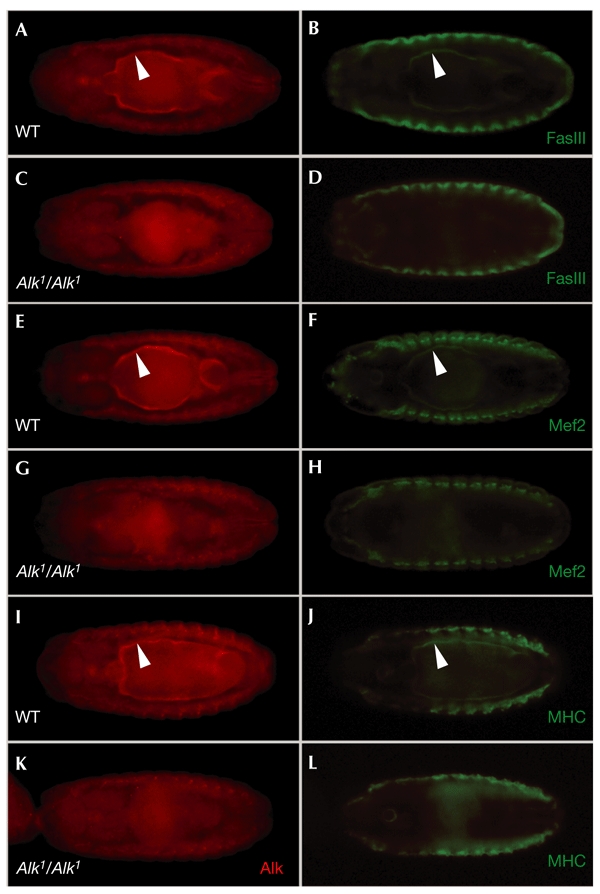

The function of Alk in visceral mesoderm development was further analysed using the immunoglobulin domain adhesion molecule Fasciclin III (FasIII), which is a marker for differentiated visceral mesoderm in the Drosophila embryo. In wild-type embryos, Alk and FasIII expression patterns overlap perfectly in the visceral mesoderm as the midgut forms (Fig. 3A,B). Further analysis of Alk mutant embryos shows that there was a complete loss of Alk-positive and FasIII-positive cells, whereas FasIII staining in the epidermis was normal (Fig. 3, compare B and D). Similar results were obtained when antibodies to Drosophila Myocyte enhancer factor 2 (Mef2), which is produced in all muscle lineages of the Drosophila embryo (Lilly et al., 1994; Nguyen et al., 1994), were used (Fig. 3E–H). Furthermore, anti-myosin-heavy-chain (MHC) staining, which showed the thin layer of gut mesoderm in wild-type embryos (Fig. 3J), was absent from Alk mutant animals (Fig. 3L).

Figure 3.

Drosophila Anaplastic lymphoma kinase is crucial for visceral mesoderm development. Visceral mesoderm does not form in Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Alk) mutant animals, as visualized by loss of several visceral mesoderm markers. Ventral views of stage 15 embryos are shown. (A) Wild-type (WT) embryo stained with anti-Alk. (B) WT embryo stained with anti-Fasciclin III (FasIII). (C) Alk1 mutant embryo stained with anti-Alk. (D) Alk1 mutant embryo stained with anti-FasIII. (E) WT embryo stained with anti-Alk. (F) WT embryo stained with anti-Mef2 (Myocyte enhancer factor 2). (G) Alk1 mutant embryo stained with anti-Alk. (H) Alk1 mutant embryo stained with anti-Mef2. (I) WT embryo stained with anti-Alk. (J) WT embryo stained with anti-MHC (mysosin heavy chain). (K) Alk1 mutant embryo stained with anti-Alk. (L) Alk1 mutant embryo stained with anti-MHC. Alk mutant embryos were identified by the absence of a lacZ balancer.

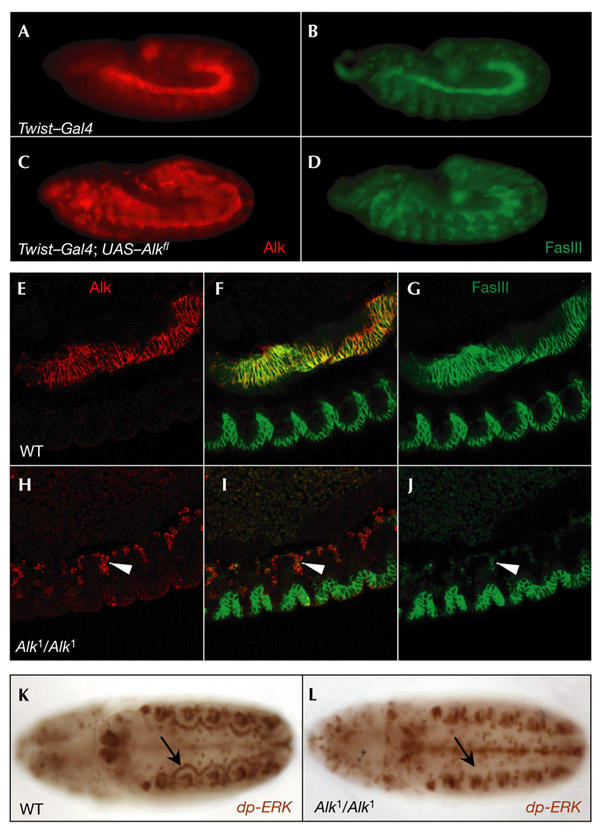

To test whether Alk is sufficient for FasIII activation, we expressed UAS–Alk (an Alk transgene under the control of the yeast Gal4 upstream activating sequence) using the mesodermal twist–Gal4 driver. Indeed, we found that Alk induced ectopic expression of FasIII (Fig. 4, compare B and D), supporting the idea that Alk controls FasIII expression. This is an exciting possibility, as the forkhead-domain transcription factor, Drosophila FoxF/Biniou, has been reported to drive expression of visceral mesoderm markers, including FasIII (Perez Sanchez et al., 2002; Zaffran et al., 2001), and Drosophila FoxF/Biniou could potentially be activated by an Alk RTK signalling pathway, as Alk is a member of the Insulin receptor RTK superfamily (Loren et al., 2001). As we saw induction of FasIII expression on Alk expression, we carefully re-examined Alk mutant embryos. Using confocal microscopy, we were able to locate scattered Alk-positive cells in Alk1 mutant animals (Fig. 4H). This is possible as the anti-Alk antibodies are raised against the extreme amino-terminal end of Alk and therefore detect the Alk1 truncated protein (see supplementary information online). On closer inspection, these cells are also seen to be weakly FasIII-positive (Fig. 4J). Thus, although FasIII expression seems to be significantly reduced in visceral mesoderm cells in Alk mutants, it is not absent. Nevertheless, full FasIII expression may still require Alk signalling through a FoxF/Biniou-mediated pathway, especially as it has been reported that there may be a positive-feedback pathway that reinforces FasIII expression (Zaffran et al., 2001).

Figure 4.

Drosophila Anaplastic lymphoma kinase regulation of Fasciclin III and extracellular-signal-related kinase in the visceral mesoderm. (A–D) Animals overexpressing Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Alk) show induction of ectopic Fasciclin III (FasIII). Lateral views of stage 12 embryos are shown. (A) Twist–Gal4 embryo stained with anti-Alk. (B) WT embryo stained with anti-FasIII. (C) Twist–Gal4; UAS–Alk embryo stained with anti-Alk (red). (D) Twist–Gal4; UAS–Alk embryo stained with anti-FasIII. (E–J) Alk-positive cells are scattered in Alk 1 mutant embryos. (E) WT embryo stained with anti-Alk. (G) WT embryo stained with anti-FasIII. (F) Merge of (E) and (G). (H) Alk1 mutant embryo stained with anti-Alk. (J) Alk1 mutant embryo stained with anti-FasIII. (I) Merge of (H) and (J). (K–L) diphospho-extracellular-signal-related kinase (dp-ERK) staining of stage 11 embryos. (K) WT embryo. (L) Alk 1 mutant embryo. ERK activation was detected in the arches of the visceral mesoderm in WT embryos but not in the Alk1 mutant embryos (indicated by arrows). Ventral views are shown. Alk mutant embryos were identified by the absence of a lacZ balancer. UAS, yeast Gal4 upstream activating sequence.

In previous work, we proposed that Drosophila Alk is the RTK responsible for the activation of extracellular-signal-related protein kinase (ERK) that is seen in the visceral mesoderm (Gabay et al., 1997; Loren et al., 2001). The availability of Alk mutant embryos allowed us to formally test this. Analysis of Alk mutants showed that diphospho-ERK (dp-ERK) is absent from the visceral arches at stage 11 (Fig. 4, compare K and L). Thus, we conclude that the Drosophila Alk RTK is indeed crucial for ERK activation and for downstream ERK-mediated events in the visceral mesoderm.

We have shown here that the endogenous Alk RTK has a function in controlling gut development in Drosophila. The targets of Alk-mediated signalling remain to be discovered. The exciting possibility exists that Alk is the receptor for the newly discovered Jelly belly protein, which has been shown to be required for mesoderm migration and differentiation (Weiss et al., 2001). Exploring these Alk pathways and targets is an important task for the future.

Methods

Fly stocks.

Standard Drosophila husbandry procedures were followed. All Drosophila strains were maintained on standard cornmeal–molasses medium. The UAS–Alk transgenic fly line has been described previously (Loren et al., 2001). The following stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center: E10-2-40 (stock number 10815), l(2)06503, P{neoFRT}42D (stock number 2120), Twist–Gal4 (stock number 2517), w;TM3SbΔ23/Dr, CyO Kr–GFP (stock number 5194) and CyO Wg–LacZ.

Isolation of Alk mutants.

Df(2R)AlkΔ21 was isolated using a designer-deletion approach (Cooley et al., 1990). Briefly, two transposable elements flanking the Alk locus (10815 and l(2)06503) were recombined onto the same chromosome using standard genetic techniques. P-element mobilization followed by quantitational Southern blot analysis was used to identify deletion of the Alk locus, resulting in the creation of an Alk deficiency, Df(2R)AlkΔ21.

Subsequently, Alk mutants were isolated as follows: EMS mutagenesis of P{neoFRT}42D flies was carried out as described in Grigliatti (1998). Male flies were starved for 12 h before treatment with 25 mM EMS/1% sucrose for 12 h, and were mated to ES/cy virgin females. After 3–4 days, mutagenized males were discarded to ensure that only postmeiotic chromosomes were tested. Male w+ /cy progeny (each being potentially mutagenized within the deficiency region) were mated with virgin females of genotype Df(2R)AlkΔ21. In total, 4,760 w+ /cy males were tested. Sixty-eight fly strains were obtained that failed to complement Df(2R)AlkΔ21.

Complementation analysis was performed between the 68 fly strains obtained, leading to the identification of 8 independent complementation groups. Alk mutants were identified by sequence analysis. Genomic DNA from heterozygous adult flies was prepared, and sequence analysis was carried out. Alk mutants were identified from double peaks in the sequencing trace, and this was subsequently confirmed by cloning into the TOPO vector (Invitrogen) followed by further sequence analysis with vector-specific primers. These sequences showed single peaks in the sequencing trace, corresponding to either mutant or wild-type DNA.

Larval eating-assay.

Alk mutant fly lines were balanced over Cyo Kr–GFP (which carries a fusion of Kruppel (Kr) to the gene encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP)) to allow the identification of mutant first-instar larvae. Embryos were collected and raised on food that had been pre-coloured with food dye. Alk mutant larvae were identified by the absence of Kr–GFP expression.

Immunostaining.

Embryos and larval brains were fixed and immunostained as described in Loren et al. (2001). The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-β-galactosidase (diluted 1:1,500; Cappel), mouse anti-FasIII (monoclonal antibody 7G10; diluted 1:50) and monoclonal antibody 22C10 (diluted 1:20), the latter two from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, rabbit anti-Mef2 (diluted 1:500; kindly provided by B. Paterson), mouse anti-MHC (diluted 1:5) and mouse anti-dp-ERK (diluted 1:500; Sigma). The following secondary antibodies were used: biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (diluted 1:1,000), Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-guinea-pig (diluted 1:200), Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (diluted 1:1,000), Cy2-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (diluted 1:1,000, all from Jackson Laboratories), and Cy2-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (diluted 1:1,000; Amersham). Signals were developed using the Vectastain Elite ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories). Embryos were cleared in methyl salicylate (Sigma) before visualization. Embryo staging was carried out according to Campos-Ortega & Hartenstein (1997).

Anti-Alk antibodies.

DNA encoding Drosophila Alk amino acids 30–316 was subcloned into pHIS8-3 to generate a 39-kDa extracellular HIS8–Alk fusion protein. The HIS8–Alk fusion protein was induced and purified from Escherichia coli (BL21(DE3)) bacterial lysates by standard protocols using Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen). The resulting eluted HIS8–Alk recombinant protein was used for rabbit and guinea-pig immunizations. Polyclonal antibodies against HIS8–Alk were used at 1:1,000 for immunofluorescence analysis.

Other methods.

SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was carried out according to Laemmli (1970). Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford (1976). Standard molecular techniques were used for DNA manipulation (Sambrook et al., 1989).

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.nature.com/embor/journal/vaop/ncurrent/extref/4-embor897-s1.pdf).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information

Acknowledgments

R.H.P. is the recipient of grant 621-2001-1624 from the Swedish Research Council. This work was also supported by: the Swedish Society for Medical Research (SSMF), Åke Wibergs Fund, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Lars Hiertas Minne Fund and the Cancer Research Fund of Northern Sweden. T.H. is a Frank and Else Schilling American Cancer Society Research Professor.

References

- Beckmann G. & Bork P. ( 1993) An adhesive domain detected in functionally diverse receptors. Trends Biochem. Sci., 18, 40–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M.M. ( 1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem., 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Ortega J.A. & Hartenstein V. ( 1997) The Embryonic Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Springer, Berlin, Germany.

- Cooley L., Thompson D. & Spradling A.C. ( 1990) Constructing deletions with defined endpoints in Drosophila . Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 3170–3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyster J., Bai R.Y. & Morris S.W. ( 2001) Translocations involving anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). Oncogene, 20, 5623–5637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falini B. ( 2001) Anaplastic large cell lymphoma: pathological, molecular and clinical features. Br. J. Haematol., 114, 741–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto J., Shiota M., Iwahara T., Seki N., Satoh H., Mori S. & Yamamoto T. ( 1996) Characterization of the transforming activity of p80, a hyperphosphorylated protein in a Ki-1 lymphoma cell line with chromosomal translocation t(2;5). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 4181–4186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay L., Seger R. & Shilo B.Z. ( 1997) MAP kinase in situ activation atlas during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development, 124, 3535–3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigliatti T.A. ( 1998) in Drosophila: A Practical Approach (ed. Roberts, D.B.), 55–84. Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Iwahara T., Fujimoto J., Wen D., Cupples R., Bucay N., Arakawa T., Mori S., Ratzkin B. & Yamamoto T. ( 1997) Molecular characterization of ALK, a receptor tyrosine kinase expressed specifically in the nervous system. Oncogene, 14, 439–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.P., Wang H., D'Eustachio P., Musacchio J.M., Schlessinger J. & Sap J. ( 1993) Cloning and characterization of R-PTP-κ, a new member of the receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase family with a proteolytically cleaved cellular adhesion molecule-like extracellular region. Mol. Cell. Biol., 13, 2942–2951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U.K. ( 1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly B., Galewsky S., Firulli A.B., Schulz R.A. & Olson E.N. ( 1994) D-MEF2: a MADS box transcription factor expressed in differentiating mesoderm and muscle cell lineages during Drosophila embryogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 5662–5666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loren C.E., Scully A., Grabbe C., Edeen P.T., Thomas J., McKeown M., Hunter T. & Palmer R.H. ( 2001) Identification and characterization of DAlk: a novel Drosophila melanogaster RTK which drives ERK activation in vivo . Genes Cells, 6, 531–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris S.W., Kirstein M.N., Valentine M.B., Dittmer K.G., Shapiro D.N., Saltman D.L. & Look A.T. ( 1994) Fusion of a kinase gene, ALK, to a nucleolar protein gene, NPM, in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Science, 263, 1281–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris S.W., Naeve C., Mathew P., James P.L., Kirstein M.N., Cui X. & Witte D.P. ( 1997) ALK, the chromosome 2 gene locus altered by the t(2;5) in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, encodes a novel neural receptor tyrosine kinase that is highly related to leukocyte tyrosine kinase (LTK). Oncogene, 14, 2175–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H.T. & Xu X. ( 1998) Drosophila mef2 expression during mesoderm development is controlled by a complex array of cis-acting regulatory modules. Dev. Biol., 204, 550–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H.T., Bodmer R., Abmayr S.M., McDermott J.C. & Spoerel N.A. ( 1994) D-mef2: a Drosophila mesoderm-specific MADS box-containing gene with a biphasic expression profile during embryogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 7520–7524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Sanchez C., Casas-Tinto S., Sanchez L., Rey-Campos J. & Granadino B. ( 2002) DmFoxF, a novel Drosophila fork head factor expressed in visceral mesoderm. Mech. Dev., 111, 163–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch E. & Maniatis T. ( 1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss J.B., Suyama K.L., Lee H.H. & Scott M.P. ( 2001) Jelly belly: a Drosophila LDL receptor repeat-containing signal required for mesoderm migration and differentiation. Cell, 107, 387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa S., Bonkowsky J.L., Kokel M., Shyn S. & Thomas J.B. ( 2001) The derailed guidance receptor does not require kinase activity in vivo . J. Neurosci., 21, RC119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaffran S., Kuchler A., Lee H.H. & Frasch M. ( 2001) Biniou (FoxF), a central component in a regulatory network controlling visceral mesoderm development and midgut morphogenesis in Drosophila . Genes Dev., 15, 2900–2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information