Abstract

The asymmetric distribution of proteins to basolateral and apical membranes is an important feature of epithelial cell polarity. To investigate how basolateral LAP proteins (LRR (for leucine-rich repeats) and PDZ (for PSD-95/Discs-large/ZO-1), which play key roles in cell polarity, reach their target membrane, we carried out a structure–function study of three LAP proteins: Caenorhabditis elegans LET-413, human Erbin and human Scribble (hScrib). Deletion and point mutation analyses establish that their LRR domain is crucial for basolateral membrane targeting. This property is specific to the LRR domain of LAP proteins, as the non-LAP protein SUR-8 does not localize at the basolateral membrane of epithelial cells, despite having a closely related LRR domain. Importantly, functional studies of LET-413 in C. elegans show that although its PDZ domain is dispensable during embryogenesis, its LRR domain is essential. Our data establish a novel paradigm for protein localization by showing that a subset of LRR domains direct subcellular localization in polarized cells.

Introduction

The specific subcellular localization of proteins and messenger RNA is crucial for the proper functioning of polarized cells. In particular, the maintenance of epithelial cell polarity requires the specific targeting of membrane and peripheral proteins to apical and basolateral membrane domains (Nelson & Yeaman, 2001). Although the mechanisms of targeting integral basolateral membrane proteins are well documented, very little is known about those of targeting peripheral basolateral proteins (Myat et al., 1998). It is likely that anchorage of peripheral proteins relies on protein modules that can interact with peptides or lipids (Lee et al., 2002), but for most of the basolateral proteins these modules have not yet been identified.

Recent studies have identified a family of peripheral proteins—LAP (LRR (for leucine-rich repeats) and PDZ (for PSD-95/Discs-large/ZO-1)) proteins—that are involved in establishing epithelial cell polarity. Members of this protein family contain 16 LRRs at their amino termini and none, one or four PDZ domains at their carboxy termini. They are characterized by the presence of two LAP-specific domains (LAPSDa and LAPSDb; Santoni et al., 2002). The family includes four mammalian proteins (hScrib, Erbin, Densin-180 and Lano), one Drosophila melanogaster (Scribble) protein and one Caenorhabditis elegans (LET-413) protein. In scribble and let-413 mutants, cell–cell junctions are not positioned properly, resulting in severe polarity defects (Bilder & Perrimon, 2000; Borg et al., 2000; Legouis et al., 2000). Erbin was so named because it can interact through its PDZ domain with ERBB2, an epidermal growth factor receptor-related protein (Borg et al., 2000). Interestingly, LAP proteins are found at the basolateral membrane or associated with lateral junctions in polarized epithelial cells of worms, flies and humans.

Although biochemical studies have revealed a diversity of ligands for LAP proteins (Santoni et al., 2002 and references therein), the mechanisms that mediate their basolateral localization remain unknown. We report that the LRRs of LET-413 and Erbin, but not the PDZ, are essential for the basolateral localization of these proteins in epithelial cells. Moreover, we show that the LRR domain but not the PDZ domain is necessary for LET-413 to function during embryogenesis. Our data reveal a new function for LRR domains and provide in vivo evidence that proper basolateral localization is required for LAP proteins to function.

Results and Discussion

The LRRs of LAP proteins mediate basolateral localization

We generated a series of truncated LET-413 proteins and analysed their intracellular localization (Fig. 1), as well as their ability to rescue the embryonic lethality of let-413 mutants. A deletion within the LRRs (ΔLRR7–9) abolishes LET-413 membrane localization, as the protein was detected in the cytoplasm of all epithelial cells at all stages of development (Fig. 1K). Conversely, deletion of the PDZ domain (ΔPDZ), the LAPSDa (ΔLAPSDa) and the LAPSDb plus interdomain (ΔLAPSDb) did not alter the membrane localization of LET-413–GFP (green fluorescent protein; Fig. 1E,J and data not shown). In addition, the LRR domain alone was capable of driving much of the protein basolaterally (Fig. 1C).

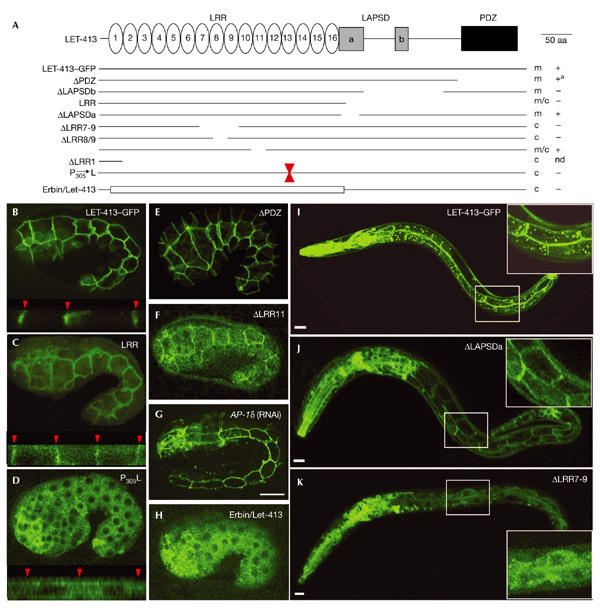

Figure 1.

The leucine-rich repeat domain of LET-413 is necessary for membrane localization. (A) Structure–function analysis of LET-413 (679 amino acids). The regions separating LAPSDa (LAP-specific domain) from LAPSDb and LAPSDb from PDZ (PSD-95/Discs-large/ZO-1) are 48 and 90 amino acids long, respectively, with no obvious motif. The coordinates of deleted amino acids are: ΔPDZ (574–679), ΔLAPSDb (423–530), LRR (393–679), ΔLAPSDa (386–427), ΔLRR7–9 (159–219), ΔLRR8/9 (192–214) and ΔLRR11 (244–266). All constructs are translational fusions with the green fluorescent (GFP) protein at the carboxy terminus. + and − indicate when a rescue of the let-413 embryonic lethality was observed. a, egg laying defect at adult stage; c, cytoplasmic localization; m, membrane localization; nd, not done. (B–K) Confocal microscopy of LET-413–GFP fusion proteins in embryos (B–H) or L2 larvae (I–K). LET-413–GFP (B, I), ΔPDZ (E) and ΔLAPSDa (J) are localized at the basolateral membrane of epithelial cells, whereas LRR (C) and ΔLRR11 (F) present both membrane and cytoplasmic localization. Quantification of confocal sections indicates that membrane-associated fluorescence is 64.8% for LET-413–GFP (B) and 45.2% for LRR (C). In P305L (D), ΔLRR7–9 (K) and Erbin/LET-413 (H) a cytoplasmic fluorescence is observed in all epithelial cells, with no vesicular localization. B–H are epidermal views of embryos at the beginning of elongation, except G which is a terminal phenotype of AP-1δ (F29G9.3RNAi). The lower parts of B, C and D are transverse views showing the epidermal cells and the lateral membranes (red arrowheads). Insets in I, J and K are intestinal cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. LAP, LRR (leucine-rich repeats) and PDZ.

We next explored whether a specific repeat or the entire LRR domain was important for targeting. We created two 23 amino acid (aa) deletions within the LRR domain: ΔLRR8/9, which deletes 6 aa of LRR8 and 17 aa of LRR9; and ΔLRR11, which removes LRR11 (23 aa). ΔLRR8/9 resulted in a complete loss of membrane localization (data not shown), but interestingly, ΔLRR11 was still partially localized to the basolateral plasma membrane (Fig. 1F). We also introduced the proline 305 to leucine substitution within LRR13 that corresponds to the let-413(s128) mutation, which is likely to be a null allele (Legouis et al., 2000). This mutation abolished membrane localization of the fusion protein (Fig. 1D). Given that this proline is present in most repeats of the C. elegans LRR protein Sur-8 and is mutated to a leucine in three out of six known mutations (Selfors et al., 1998), we suggest that this residue must be critical for the structure of the LRR domain.

We examined whether the AP-1 adaptor protein complex, which is essential for differential sorting of basolateral integral proteins, might be required for LET-413 basolateral targeting. Indeed, the loss of C. elegans clathrin AP-1 subunits leads to morphogenetic defects similar to those of let-413 mutants (Shim et al., 2000). When we used RNA interference to eliminate AP-1 expression, we obtained 100% embryonic lethality with consistent elongation defects but did not observe any change in LET-413 localization (Fig. 1G). This indicates that the LET-413 basolateral targeting is AP-1 independent.

To map the regions involved in membrane localization of Erbin, a human homologue of LET-413 (Borg et al., 2000), we expressed various GFP–Erbin constructs (Fig. 2A) in mammalian cells (Fig. 2B–D). Only the LRR domain was associated with the plasma membrane and colocalized with endogenous Erbin. The other constructs were cytoplasmic (Interdomain 1), nuclear (Interdomain 2) or both (PDZ; Fig. 2C,D). Moreover, ΔLRR, a deletion construct lacking the LRRs and the LAPSDa, was nuclear and cytoplasmic (data not shown). Identical results were obtained using HA-tagged versions of Erbin (data not shown).

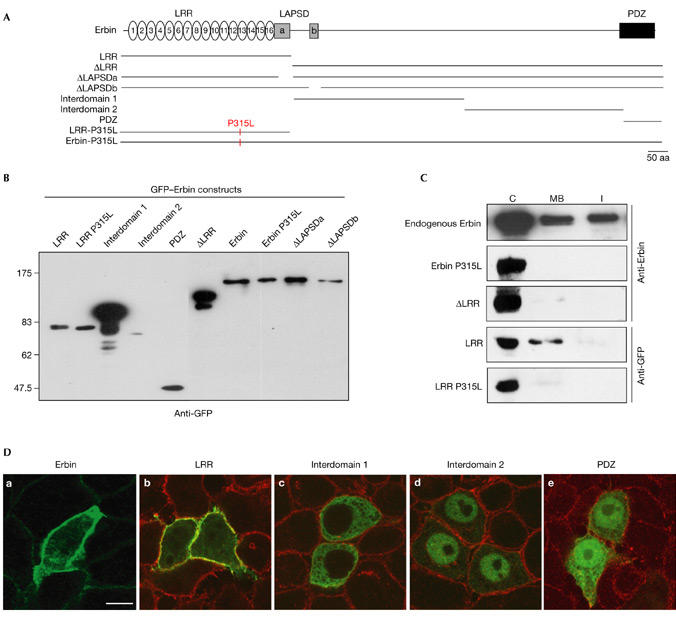

Figure 2.

Conservation of leucine-rich repeat function in the localization of Erbin. Green fluorescent protein (GFP)–Erbin constructs (A) were transiently expressed in COS-7 (B) or HeLa (C, D) cells. (C) The amounts of endogenous Erbin and GFP constructs were compared in cytosolic (C), Triton X-100-soluble membrane (MB), and Triton X-100-insoluble fractions (I). In this cellular system, endogenous Erbin is membrane associated and cytosolic. Erbin LRR shows the same localization as endogenous Erbin, whereas ΔLRR, LRR P315L and Erbin P315L are cytosolic only. (D) Confocal XY section of HeLa cells transfected with GFP Erbin fusions (green) and stained with anti-Erbin antibody (green in a; red in b, c, d) or anti-DLG (human Discs-large) antibodies (red in e). GFP–Erbin and LRR are mainly membrane associated. Other constructs are excluded from the plasma membrane: Interdomain 1 is cytosolic, Interdomain 2 is nuclear, and PDZ is cytosolic and nuclear. Scale bar, 10 μm. LRR, leucine-rich repeat; PDZ, PSD-95/Discs-large/ZO-1.

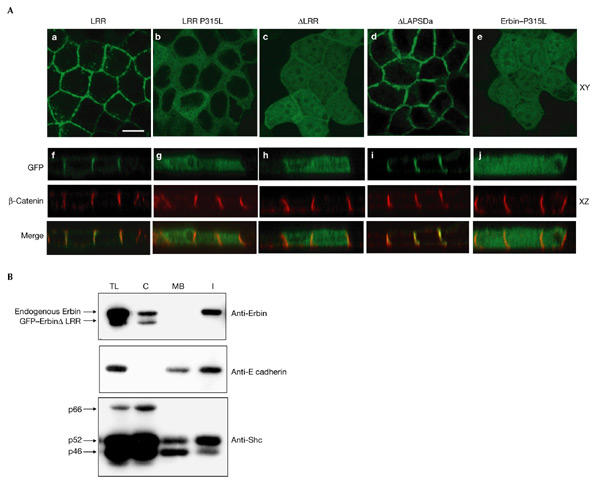

To determine the localization of these constructs in polarized epithelial cells, we produced stable Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) transfectants. Again, only the LRR domain, ΔLAPSDa and ΔLAPSDb were targeted to the basolateral membrane (Fig. 3A and data not shown). Moreover, these proteins colocalized with endogenous Erbin and with β-catenin, another marker of basolateral membranes, when polarized cells were examined in Z sections (Fig. 3A). Immunolocalization and cell fractionation experiments showed that ΔLRR mainly had a cytoplasmic and nuclear localization compared with endogenous Erbin (Fig. 3). Changing the conserved proline residue into a leucine (Erbin P315L) at a position equivalent to LET-413 proline 305 also abolished membrane localization of full-length Erbin or the LRR domain.

Figure 3.

The basolateral localization of Erbin is mediated by its leucine-rich repeats. (A) XY (a–e) and XZ (f–j) confocal sections of Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP)–Erbin constructs (green) compared with endogenous β-catenin expression (red). Leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) and ΔLAPSDa are basolateral, whereas LRR–P315L, ΔLRR and Erbin P315L present a diffuse staining. Scale bar, 15 μm. (B) The amounts of endogenous Erbin and GFP constructs in MDCK cells were assessed in total lysate (TL), cytosolic (C), Triton X-100-soluble membrane (MB) and Triton X-100-insoluble (I) fractions using anti-Erbin antibody. An important fraction of endogenous Erbin is found in the membrane Triton X-100-insoluble fractions in polarized MDCK, whereas ΔLRR is mainly cytosolic. Controls: E-cadherin is found in the membrane fraction (Triton X-100-soluble and -insoluble) and Shc proteins are mainly cytosolic.

Erbin is found in Triton-X100-insoluble fractions in Hela cells (18% of total Erbin), as well as in the Triton-X100-soluble fractions, (21%) and the cytosol (61%; Fig. 2C). In polarized MDCK cells, a smaller proportion of Erbin is cytosolic (39%) and the rest (61%) is recovered in the Triton-X100-insoluble fraction (Fig. 3B). This difference is probably caused by the engagement of Erbin in Triton-X100-insoluble rafts (Foster et al., 2003) or cytoskeleton-associated protein networks in polarized epithelial cells. The LRR domain (73% cytosolic and 27% in the Triton-X100-soluble fractions in Hela cells) lacks association to Triton-X100-insoluble compartments, suggesting that other parts of Erbin participate in this recruitment.

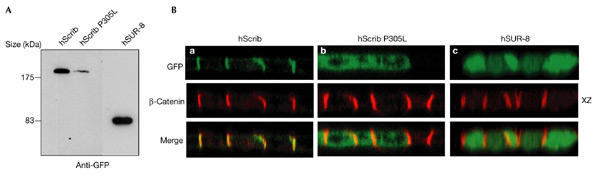

To assess whether related LRR domains from non-LAP proteins also mediate basolateral targeting, we examined the behaviour of human SUR-8, which contains an LRR domain similar to Erbin LRRs (30% identity). When expressed as a GFP fusion in MDCK cells, SUR-8 was not localized at the plasma membrane (Fig. 4). This result emphasizes the specific function of the LRR domain of LAP proteins.

Figure 4.

Basolateral localization by the leucine-rich repeat domain is a characteristic of the LAP family. (A) Western blot analysis of green fluorescent protein (GFP)–hScrib (wild-type or mutant P305L) and GFP–human SUR-8 expressed in Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells. Proteins were detected with an anti-GFP antibody. (B) Confocal XZ section of GFP–hScrib constructs (green) compared with that of endogenous β-catenin (red). The proline 305 mutation in Scribble LRRs abolishes membrane localization (compare a and b). GFP–hSUR-8 is cytoplasmic. LAP, LRR (leucine-rich repeat) and PDZ (PSD-95/Discs-large/ZO-1).

Lano, a mammalian LAP protein that only contains 16 LRRs and two LAPSDs (Saito et al., 2001) is localized basolaterally, which is consistent with our findings. Furthermore, mutation of the conserved proline within the LRR13 of hScrib and Lano also affects the basolateral localization of these proteins (Fig. 4B and data not shown). Together, our results strongly suggest that the basolateral localization mediated by their 16 LRRs is a general feature of LAP proteins.

LET-413 domains required for LET-413 embryonic function

To test whether the deletions described above affect LET-413 function, we introduced the LET-413–GFP constructs in a let-413-deficient background (see Methods). None of the constructs that prevent membrane localization (ΔLRR7–9, ΔLRR8/9 and P305L; Fig. 1) could rescue, with arrested embryos presenting the characteristic phenotypes of let-413 null mutants. These data support the idea that membrane localization of LET-413 is necessary for the protein to function normally. Although the LRR domain was sufficient to drive some of the protein to the basolateral membrane, it did not rescue let-413-deficient embryos (Fig. 1), suggesting that other domains of the protein might be essential for its function. Indeed, the ΔLAPSDb construct could not rescue the let-413 mutants, indicating that this region, which is not necessary for LET-413 localization, is nevertheless crucial for its activity. By contrast, ΔLAPSDa could rescue the phenotype of let-413-deficient animals. This is surprising because this motif is very well conserved between LET-413 and other LAP proteins (60% identity). Likewise, ΔPDZ, which totally removes the PDZ domain, was able to rescue the embryonic lethality of let-413-deficient animals. Although let-413 mutant animals that are transgenic for the ΔPDZ construct developed normally until the adult stage, they presented egg-laying defects (data not shown).

To test whether the LRRs of Erbin could replace the LRRs of LET-413, we constructed a chimeric LAP by replacing the LRR domain of LET-413 by that of Erbin. The Erbin/LET-413 was found exclusively in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1H) and could not rescue the let-413 phenotype, confirming the strict relationship between membrane localization and function. Similarly, the expression of LET-413 in MDCK cells showed that the worm protein is not localized to the plasma membrane in mammalian cells (data not shown). Several hypotheses can explain why Erbin LRRs cannot substitute for LET-413 LRRs. LET-413 is the most divergent member of the LAP family and its identity with Erbin LRR domain is only 40%, which could preclude the binding of an orthologous interacting protein. Alternatively, Erbin, which is one of several human LAP proteins, could have a different LRR-binding partner than does LET-413.

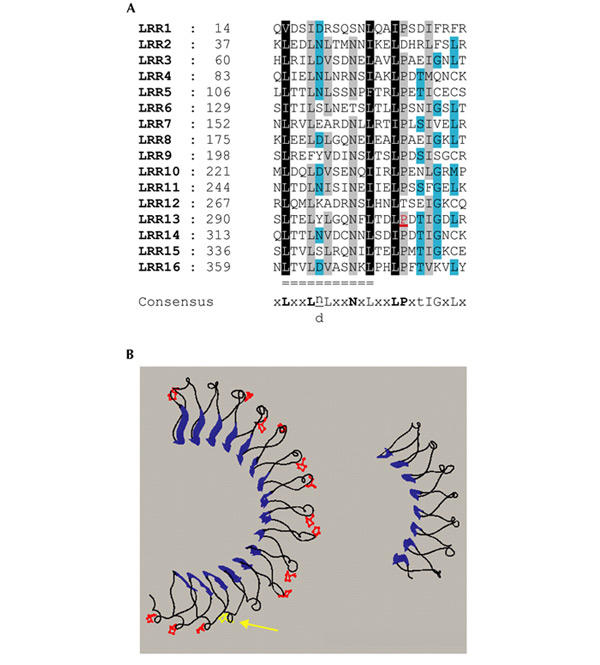

Molecular modelling of LET-413 leucine-rich repeats

Recently, crystal structures of several LRR-containing proteins have been reported (Kajava & Kobe, 2002). They show that all β-strands and α-helices are parallel to a common axis and form a horseshoe-like structure, with β-strands forming the inner circumference and α-helices forming the outside surface. On the basis of their leucine skeleton, LRRs can be assigned to different subfamilies (Kajava & Kobe, 2002). We defined a 23-aa consensus sequence for the 16 LRRs of LET-413 (xLxxLnLxxNxLxxLPxtIGxLx; Fig. 5A). Because no crystal structure of the 23-aa classical LRR family has yet been established, we generated a structural model for the LET-413 LRR domain (Fig. 5B) using internalin B (InlB) as a template for modelling (Marino et al., 1999). Our model suggests that the proline 305 is located at the external surface of the helicoidal part of the structure. The crystal structures of LRR domains with their ligands clearly show binding of the ligand in the concave part of the domain. We suggest, therefore, that the P305L mutation affects the local structure of the helicoidal part of LRR13, and in turn the binding potential of the entire domain. However, we cannot exclude that the LRRs of LAP proteins bind to interacting proteins by their external surface.

Figure 5.

A structural model for LET-413 leucine-rich repeats. (A) Alignments of leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) of LET-413 were obtained with Clustal X, using the BLOSUM 35 matrix. Black squares denote 100% of residues with the same properties, grey more than 80% and turquoise more than 60%. Bold uppercase letters in the consensus indicate more than an 80% occurrence of a given residue, normal uppercase letters indicate more than 50% and lowercase letters indicate more than 30%. Double lines indicate the 11 residues corresponding to the invariant part of the LRR forming the β-strand and loop region. The proline residue in red is transformed into a leucine by the mutation let-413(s128). (B) Structural model of the LET-413 LRR domain (left) using as template the internalin B protein (right; PDB ). The β-strands are shown as large blue arrows, the conserved proline residues are in red and the residue P305 is in yellow (arrow).

Our data suggest a model whereby the localization of LAP proteins depends on LRR-binding proteins localized at the plasma membrane. We cannot rule out the possibility that the LRRs bind directly to a lipid such as phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, in a similar way to pleckstrin homology (PH) and PDZ domains (Cullen et al., 2001; Zimmermann et al., 2002). However, the tests for this type of binding were negative (P. Zimmermann & G. David, personal communication). Because none of the LET-413 or Erbin constructs were observed at the apical membrane, we hypothesize that proteins tethering the LRR domain of LAP proteins to the plasma membrane are themselves restricted to the basolateral domain. Despite the great variety of LRR ligands, several observations designate small GTPases to be good candidates as interacting partners. In particular, there is good similarity between the LRRs of LET-413 and SUR-8, which binds the GTPase Ras (Goshima et al., 1999; Sieburth et al., 1998). Furthermore, small GTPases can provide membrane tethering through different motifs (Choy et al., 1999). Two-hybrid tests in yeast failed to reveal any interaction between Erbin and the small GTPases Ras, Rap, Ral, Arf6, Cdc42, Rac and Rho (data not shown), leaving the identity of the putative GTPase interacting with LAP proteins to be discovered.

In summary, we have uncovered a new paradigm for basolateral localization, which operates in differentiating epithelial cells. The identification of the interacting partners of the LAP LRR domains will help to understand the process involved in their basolateral localization and elucidate the pathway responsible for the establishment of cell–cell junctions in epithelial tissues.

Methods

Molecular biology.

LET-413 constructs were generated from pML801, a plasmid containing a functional translational fusion of the entire let-413 gene with the GFP cDNA (Legouis et al., 2000). In-frame deletions were obtained either by restriction enzyme digestion and religation or by long-range PCR. The P305L mutation was obtained by a two-step PCR procedure with the Expand High-Fidelity PCR System (Roche).

Full-length or truncated versions of human erbin produced by PCR were cloned into the GFP–C1 (Clontech) or pCDNA–HA (Stratagene) vectors. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuickChange kit (Stratagene). All constructs were sequenced by Genome Express (Grenoble, France).

Caenorhabditis elegans techniques.

Animals were manipulated and microinjected as described previously (Legouis et al., 2000). Strains used in this studies were: N2, let-413(s128)unc-42(e270)/dpy-11(e224) and dpy-11(e224)let-413(s1455)/unc-42(e270)rol-3(e754). For each construct, at least three independent strains were observed by microscopy. Confocal observations were done on 3–5 embryos and larvae. The rescuing ability of deleted constructs was tested either by injection into let-413 mutants and/or by 3′-untranslated region (UTR) RNA interference (RNAi) experiments (McMahon et al., 2001). Double-stranded RNA corresponding to the 3′UTR of let-413 was injected into transgenic strains carrying the different LET-413–GFP deletions. Because GFP constructs contain the unc-54 3′UTR sequence and not that of let-413, transcripts produced from the transgene remained resistant to RNAi. For each strain, the numbers in brackets indicate the percentage of transgene transmission and the percentage of survival after RNAi: wild-type (0/0.2), LET-413–GFP (100/97.3), ΔLAPSDa (55/42.7), ΔLAPSDb (100/0.6), LRR (60/0.4), ΔLRR11 (65/54.6), ΔLRR8/9 (60/6.0), ΔLRR7–9 (68/12.0), P305L (60/1.4), ΔPDZ (65/59) and LET-413(ErbinLRR) (35/1.8).

Quantification of cytoplasmic and membrane signals for LET-413–GFP and LRR was performed using Metamorph software. Five embryos were used for both LET-413–GFP and LRR, and 85 and 78 confocal sections were obtained, respectively, with no signal saturation, and which correspond to 745 and 774 cell sections. Areas corresponding to the whole cell or the cytoplasmic compartment were determined manually and then quantified.

Cell culture.

Culture, transfection and immunocytochemistry on Hela and MDCK cells were done as previously described (Borg et al., 2000). For each construct, at least three independent experiments have been performed. Several hundreds of GFP-positive cells were observed, of which more than 75% presented a similar phenotype. Antibodies used were rabbit polyclonal anti-Erbin, monoclonal anti-β-catenin and Discs-large (Transduction Laboratories).

Cell fractionation.

After lysis in hypotonic buffer, sucrose was added to the homogenate to a final concentration of 0.25 M, and non-homogenized debris were removed by centrifugation at 1,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 138,000g for 1 h at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and was termed the cytosolic fraction. The pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, and the insoluble fraction was isolated by centrifugation at 16,000g for 30 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was termed the membrane fraction.

Leucine-rich-repeat domain modelling.

Blast2 alignments showed that among LRR-containing proteins present in Protein Data Bank, the LRR of internalin B precursor is the most closely related to LET-413. It was thus used as a template for modelling with the Swiss-pdb-Viewer program. The invariant part of the motif was manually aligned to the template structure. Because LET-413 repeats are one residue longer than internalin repeats, a gap was introduced in the helicoidal domain of the internalin template. The position of the gap was chosen according to Kajava & Kobe (2002).

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to G. Truan for the molecular modelling of LET-413. We thank X. Gauthereau, S. Sookhareea, J. Camonis, P. Chavrier, D. Isnardon and R. Galindo for technical help and reagents, and P. Follette and R. Karess for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Hopitaux Universitaires de Strasbourg, the INSERM APEX programme (M.L. and J.P.B.), grants from the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (M.L.), the Action Concertée Incitative Jeune Chercheur (R.L. and J.P.B.), the Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale (R.L.), la Fondation de France, Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer and Institut Paoli-Calmettes (J.P.B.). F.J.B. is a recipient of a Ministere de la Recherche et de la Technologie fellowship and C.N. of a Conseil General/Ipsogen fellowship.

References

- Bilder D. & Perrimon N. ( 2000) Localization of apical epithelial determinants by the basolateral PDZ protein Scribble. Nature, 403, 676–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg J.P. et al. ( 2000) ERBIN: a basolateral PDZ protein that interacts with the mammalian ERBB2/HER2 receptor. Nature Cell Biol., 2, 407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy E. et al. ( 1999) Endomembrane trafficking of ras: the CAAX motif targets proteins to the ER and Golgi. Cell, 98, 69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen P.J., Cozier G.E., Banting G. & Mellor H. ( 2001) Modular phosphoinositide-binding domains—their role in signalling and membrane trafficking. Curr. Biol., 11, R882–R893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster L.J., De Hoog C.L. & Mann M. ( 2003) Unbiased quantitative proteomics of lipid rafts reveals high specificity for signaling factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 5813–5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshima M. et al. ( 1999) Characterization of a novel Ras-binding protein Ce-FLI-1 comprising leucine-rich repeats and gelsolin-like domains. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 257, 111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajava A.V. & Kobe B. ( 2002) Assessment of the ability to model proteins with leucine-rich repeats in light of the latest structural information. Protein Sci., 11, 1082–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Fan S., Makarova O., Straight S. & Margolis B. ( 2002) A novel and conserved protein–protein interaction domain of mammalian Lin-2/CASK binds and recruits SAP97 to the lateral surface of epithelia. Mol. Cell. Biol., 22, 1778–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legouis R. et al. ( 2000) LET-413 is a basolateral protein required for the assembly of adherens junctions in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature Cell Biol., 2, 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino M., Braun L., Cossart P. & Ghosh P. ( 1999) Structure of the lnlB leucine-rich repeats, a domain that triggers host cell invasion by the bacterial pathogen L. monocytogenes . Mol. Cell, 4, 1063–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon L., Legouis R., Vonesch J.L. & Labouesse M. ( 2001) Assembly of C. elegans apical junctions involves positioning and compaction by LET-413 and protein aggregation by the MAGUK protein DLG-1. J. Cell Sci., 114, 2265–2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myat M.M., Chang S., Rodriguez-Boulan E. & Aderem A. ( 1998) Identification of the basolateral targeting determinant of a peripheral membrane protein, MacMARCKS, in polarized cells. Curr. Biol., 8, 677–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson W.J. & Yeaman C. ( 2001) Protein trafficking in the exocytic pathway of polarized epithelial cells. Trends Cell Biol., 11, 483–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H. et al. ( 2001) Lano, a novel LAP protein directly connected to MAGUK proteins in epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 32051–32055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoni M.J., Pontarotti P., Birnbaum D. & Borg J.P. ( 2002) The LAP family: a phylogenetic point of view. Trends Genet., 18, 494–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selfors L.M., Schutzman J.L., Borland C.Z. & Stern M.J. ( 1998) soc-2 encodes a leucine-rich repeat protein implicated in fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 6903–6908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim J., Sternberg P.W. & Lee J. ( 2000) Distinct and redundant functions of mu1 medium chains of the AP-1 clathrin-associated protein complex in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell, 11, 2743–2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieburth D.S., Sun Q. & Han M. ( 1998) SUR-8, a conserved Ras-binding protein with leucine-rich repeats, positively regulates Ras-mediated signaling in C. elegans . Cell, 94, 119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P. et al. ( 2002) PIP(2)-PDZ domain binding controls the association of syntenin with the plasma membrane. Mol. Cell, 9, 1215–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]