Summary

Zoonoses, diseases that jump from animals to humans, are a growing health problem around the world. Understanding their causes and their effects on humans have therefore become an important topic for global public health

In their 1975 satire on the King Arthur saga, the movie 'Monty Python and the Holy Grail', the British comedy group Monty Python included a scene with a dangerous animal. While on their search for the Holy Grail, King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table have to enter the Cave of Caerbannog. But Tim, a Scottish sorcerer, warns them of the fierce rabbit that guards the cave's entrance: “That's the most foul, cruel and bad-tempered rodent you ever set eyes on.” Arthur does not believe a word and loses about a dozen of his knights in the fight against the killer rabbit. If you overlook the grisly details, this is a wonderful joke that attributes the characteristics of a deadly predator to a cute and cuddly animal. The US government did not take any chances with cute animals earlier this year. In June, it prohibited the import, sale and distribution of six African rodent species after more than 50 people in the USA became infected with monkeypox virus that was most likely transmitted from rodents imported from Africa as pets. On June 11 of this year, it also recommended smallpox vaccinations to curtail further human-to-human transmission of monkeypox, which is closely related to smallpox and fatal in up to 10% of cases. Only one day later, health officials in Wisconsin confirmed that a health-care worker was infected with the virus as a result of human-to-human transmission.

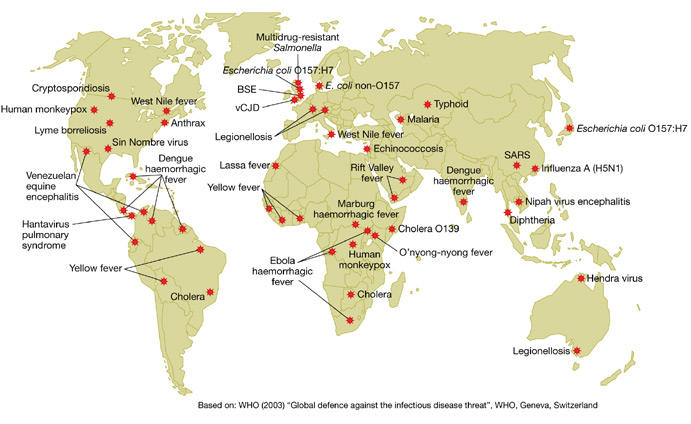

Monkeypox, the recent SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome, caused by a previously unknown strain of coronavirus) epidemic, the spread of West Nile virus across North America and the 1997 avian flu outbreak in Hong Kong that killed six people, highlight the danger of zoonoses, which are pathogens that lurk in animals and are able to make the species-jump to infect humans. And it seems that zoonoses are increasing, with more than 200 known zoonotic diseases that have emerged and re-emerged all over the globe (Fig. 1; Table 1). “It is just a continuing trend,” Harvey Artsob, Chief of Zoonotic Diseases at Health Canada's National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg, Manitoba, commented, “There has been an increase over the last 30 years.” What makes scientists and health officials worry most, however, are not the diseases they already know, but those that are new and unknown. “Something new will happen and it will be unexpected,” Robin Weiss, Chairman of the Windeyer Institute of Medical Sciences at University College London, UK, and Director of its Wohl Viron Centre, said: “Who could have predicted something like SARS?” For experts such as Weiss or Artsob, it is not the question of 'if', but 'when' the next zoonotic disease will strike. Consequently, much research is now focused on what makes viruses, microorganisms and parasites cross the species barrier from their animal host to humans, what effects this host change may have on humans, how such diseases spread and how they might be controlled before they become a global epidemic.

What makes scientists and health officials worry most, however, are not the diseases they already know, but those that are new and unknown

Figure 1.

Global outbreaks of zoonoses. BSE, bovine spongiform encephalopathy; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; vCJD, variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease.

Table 1.

Examples of zoonotic outbreaks over the past 30 years

| Pathogen | Animal reservoir | Location | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillius anthracis | Cattle | USA | 2001 |

| Borrelia burgdorferi | Deer, mice | USA | Endemic |

| BSE/vCJD | Cattle | UK | 1996 |

| CCH | Sheep, hare | Bulgaria | 1994 |

| Ebola virus | Unknown | Sudan/DRC | 1976 |

| DRC | 1995 | ||

| Gabon | 1996 | ||

| Uganda | 2000 | ||

| Escherichia coli O157:H7 | Cattle | UK | 1996 |

| Sin Nombre virus | Rodent | USA | 1993 |

| Hendravirus | Bat | Australia | 1997 |

| HIV | Monkey | Global | Endemic |

| Influenza H5N1 | Duck, quail | Hong Kong | 1997 |

| Lassa fever virus | Rodent | Liberia/Sierra Leone | 1977 |

| Marburg virus | Monkey | Germany | 1975 |

| Monkeypox | Rodent | USA | 2003 |

| Nipah virus | Bat | Malaysia | 1998 |

| Sabia virus | Unknown | Brazil | 1994 |

| SARS | Mammals | Southern China | 2002 |

| Toxocara canis | Dog | Worldwide | Sporadic |

| VEE | Horse | Mexico | 1995 |

| West Nile virus | Bird | USA | 1999 |

| Yellow fever virus | Monkey | Africa | Endemic |

| Yersinia pestis | Rodent | India | 1994 |

BSE, bovine spongiform encephalopathy; CCH, Crimean–Congo haemorrhagic fever; DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; vCJD, variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease; VEE, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus.

Whether the current increase in zoonoses is due to previously unknown or to re-emerging pathogens is a topic of much debate. “I am sceptical that the rate of [new] zoonotic events has rated up,” Weiss cautioned. “There has certainly been an increase in fashion,” he said, but pointed out that many outbreaks were caused by re-emerging pathogens. “How do we know it never happened before?” he asked. Indeed, if SARS had taken place during Marco Polo's travels to China, he said, it would have been mostly a local outbreak and gone largely unnoticed. Daniel S. Shapiro, Director of the Clinical Microbiology and Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory at the Boston Medical Center and Associate Professor of Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine (MA, USA), also questioned if there is a real increase, or just better disease surveillance and new molecular methods to detect pathogens. But most agree that zoonotic diseases in general are on the rise. “Certainly the conditions are such that we might anticipate more zoonotic events,” Shapiro commented. And according to Weiss, “the really big question is how can we determine which will peter out and which will become a global epidemic?” It is indeed an important question, given that zoonoses not only cause an enormous amount of human death and suffering, but also lead to considerable economic costs as well—the SARS outbreak is estimated to have cost US $100 billion globally.

The main cause of zoonoses is activity that brings humans into closer contact with animals. According to Herbert Schmitz, head of the Department of Virology at the Bernhard Nocht Institute of Tropical Medicine in Hamburg, Germany, any such contact could potentially create a new disease, and the more intense the contact, the higher the probability. “If there are enough virus particles and the mutation rate is high enough, particularly with RNA viruses, then one in a million is able to infect humans under certain circumstances,” he said. Regions with large biodiversity, such as the Amazon basin and the rainforests of Africa and Southeast Asia, are the most risky areas in this regard, he said, adding “and at the same time, these are regions where man increasingly invades.” Human encroachment into formerly wild habitats is therefore one of the main reasons for emerging zoonoses. The Ebola and Marburg viruses infected bushmeat hunters and wood gatherers who invaded African rainforests. The outbreak of Nipah virus in Malaysia in 1998 was a result of pig farmers moving nearer to and into forests. The virus, normally found in bats, first infected domesticated pigs, and then jumped to farmers. But it is not only exotic animals in rainforests that cause zoonoses. Expanding suburbs in the USA and recreational activity in North American forests bring humans into closer contact with deer and ticks, the latter being the vector for Borrelia burgdorferi, which infects more than 16,000 Americans each year.

For experts such as Weiss or Artsob, it is not the question of 'if', but 'when' the next zoonotic disease will strike

In addition, international trade provides new opportunities for pathogens to infect humans; the recent outbreak of monkeypox in the USA is a prime example. “This makes me wonder,” Schmitz commented, “The Americans have very strict rules and controls and then they go on and import whole living animals that are known to harbour monkeypox virus.” Equally, the spread of West Nile virus in the USA, which first arrived on the continent in 1999, was most likely caused by birds or mosquitoes that somehow hitchhiked to the USA. Even more important is the role of human travel. “To some extent, we have increased risks with travel,” Artsob said. SARS was only able to spread throughout the world with the helping hand of travellers, and, ironically, it may have been the severity of the disease that prevented a greater epidemic. “It was an advantage that these people were severely ill and did not take the subway or the plane but went to a hospital,” Schmitz said. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) may have jumped on several occasions from chimpanzees to humans in past centuries, but it became a global problem when human travel spread the virus around the world. And it may become an even larger problem as more people travel to more obscure locations. “I think there are a lot of animal viruses in Africa but fortunately not many people there travel by plane,” Schmitz said.

Given that it is the close contact between humans and animals that gives a pathogen the opportunity to jump species, changes in agricultural practices also increase the risk of zoonoses. During human history, many pathogens, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis or influenza virus, have easily crossed the barriers between humans and domestic animals. The recent SARS outbreak originated in southern China, where farmers are in close contact with animals. And new farming methods increase these chances even more. Shapiro pointed to bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) as a result of “factory farming” as he called it, and of feeding practices that allowed infectious prions to jump from sheep to cattle and subsequently to humans.

SARS was only able to spread throughout the world with the helping hand of travellers...

Climate change is another factor that helps to increase contact between humans and animals. An unusually high amount of rain in southwest USA after global climatic changes in 1993/94 and 1998/99 boosted vegetation growth and allowed for a rise in the rodent population. At the same time, there was an outbreak of Sin Nombre virus, a hantavirus, in humans in the same areas. The virus spread from its rodent reservoir to humans when humans came into contact with infected rodent faeces. And experts fear that global warming, now widely acknowledged, will contribute to more zoonotic events as animals, particularly mosquitoes, are able to invade new areas.

The next question, then, is which of these new diseases will survive in humans and spread, and which will dissipate? “The real public health problem arises when the species jump is followed by very efficient spread among the human population,” Shapiro said. As Weiss pointed out, in some cases, the symptoms of an infection can be directly translated into transmission among humans, such as the shed of the Ebola virus through blood and faeces or the release of influenza virus through coughing. Other viruses are not so successful. Outbreaks of monkeypox in Africa have shown that this virus loses its ability to infect humans with subsequent human-to-human transmission. Finally, some pathogens, such as the rabies-causing Lyssavirus or B. burgdorferi, are primary zoonoses that act only through animal–human contact. In addition, pathogenesis and virulence have a role. Because HIV acts slowly, an infected person can remain undiagnosed for a long time and thus spread the virus efficiently. Conversely, Ebola is so virulent, with a mortality rate of more than 90%, that various outbreaks in Africa died out before the virus was able to spread further. Also, because it acts so quickly and causes severe symptoms, health officials are able to react in time and enforce quarantine measures to contain the virus. In addition to subsequent human-to-human transmission, there is the additional danger that new zoonoses will establish a foothold in their new location “just as West Nile virus has entered many new species in the Western hemisphere,” Shapiro said. One concern during the recent monkeypox outbreak in the USA was the possibility that pet owners would release infected rodents into the wild, where they potentially could infect local rodents and establish monkeypox among native American rodents, he said.

Given the catastrophic consequences of many zoonotic diseases, experts think that public health officials should pay much more attention to improving the surveillance of wild and domestic animals. The World Health Organization (WHO) set up its Global Influenza Surveillance Network to monitor new flu strains in birds and pigs and to make recommendations for new vaccines. This network also proved to be immensely helpful during the SARS epidemic and largely contributed to the WHO's success in containing the disease. Equally, Europe now demands mandatory BSE tests of cattle to keep the disease under control. Some states in the USA use sentinel chickens to screen for West Nile virus and other diseases on the basis of the observation that the outbreak of the virus in New York was preceded by a large number of bird deaths. But many zoonoses still remain unmonitored. The political situation in Central Africa, particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo, prevents any surveillance of the Ebola or Marburg viruses and AIDS/HIV is far from being efficiently monitored in Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe. Schmitz also pointed to better surveillance of imported animals, citing the 1975 outbreak of Marburg virus in Germany, when one infected monkey transmitted the virus to other monkeys during transportation, which was then sufficient to infect some of the animal keepers.

But the real fear is about the unknown pathogens that still lurk in the wild. Indeed, “a good measure is just knowing what we are dealing with”, Schmitz said. Shapiro pointed out that systematic ways of looking for new diseases are one preventive measure. “There are limited attempts to define the sea of microorganisms that we swim in,” Shapiro said, such as molecular analysis of animals and their viruses in the Amazon basin. Other projects search for relatives of known pathogens to try and analyse them on a molecular level, or investigate the deaths of persons who died of unknown causes. But although “these settings are examples where the science runs well ahead of the clinical data,” he thinks that, inevitably, finding new diseases is an impossible task.

Consequently, public health is left to deal with new outbreaks and so clearly more awareness of zoonoses is needed. “Both veterinary public health and human public health makes sense in this context,” Shapiro said. As human trade and travel can quickly turn a local outbreak into a global epidemic, a better global awareness of the problem is needed as well. “I think we need to do a few things: one is that the international boundaries in public health surveillance have to be recognized as a major problem,” Shapiro said, “You need to have a barrier-free situation when we're dealing with infectious diseases.” In addition, more research into new vaccines and drugs is required, particularly to counter the threat of viral zoonoses. Given that vaccine and antiviral research are not high priorities for the pharmaceutical industry, Shapiro thus pointed to public–private partnerships as a possible solution to developing treatments against new diseases. Nevertheless, these partnerships rely on the goodwill of politicians for support, so a better awareness of the threat of zoonotic diseases among public-health officials and politicians is certainly necessary. But the complexity of the problem, its global extent and the many factors that have a role in emerging diseases make it almost impossible to predict and counter them efficiently. “We couldn't have a strategy to predict all these things. We could only react,” Artsob said. “I don't know how you can stop some of these diseases from emerging.”