Cherubs, Citizens and Titian

The (excellent) audio programme for this exhibition refers to Scotland as a European country and to the ‘embracing of other cultures’. It suggests that the ‘luscious and sensuous Titian’ paintings would, even on a ‘Scottish dreicha January day’, be heartwarming. The day I saw it was in August and, atypically for this August, it was not dreich but the paintings were, indeed, exhilarating and heartwarming.

Tiziano Vicellio lived between about 1485 and 1576 and trained with Bellini. When Bellini died, Titian was in his late twenties and became the official painter of Venice. The Venetian painters affected the transition between the Gothic style of the late middle ages and the logic and realism of Renaissance narrative. Venice was a bridge between east and west and Venetian art reflected that; the colours were brilliant and the fabrics and textures rich. Wealth was founded on trade in the near east and the colonies in the Adriatic, Greece and the eastern Mediterranean. The city state was governed by a merchant elite as a republic and the Venetians were very proud of a republican constitution, which they believed gave them a liberty and justice denied to citizens of virtually every other state of the period. They saw it as a divine gift bestowed on them as a people specially favoured by God.

The power of the church is evident in the subject matter of the paintings and the way in which the church often dictated what was appropriate to be included. The painter of a work depicting the last supper had to rapidly rename it when it became clear that the church authorities considered some of the characters to be too frivolous for such a serious subject. The historical and social context is fascinatingly described in the exhibition's commentary. Portraits of women were rare in Venetian art and, until Titian, they tended to have little power in the composition. The wonderful Venus Anadyomene (‘Venus rising from the sea’) shows her dominating the landscape, lost in her own thoughts and unconcerned by us, the viewers.

The techniques used to combine images, long predating digital photography, achieve results that modern photographers admire and emulate. In Three Ages of Man, the one canvas contains images of (cherubic) infancy, young love with the near-naked lovers staring into each other's eyes and holding, but not playing, flutes and old age with an old man in the distance holding two skulls. Music is the food of love but playing is deferred since the theme, the transience of human life and love, is too serious. All this in a sublime pastoral setting gives further information about Venetian values and the importance that they attached to the countryside.

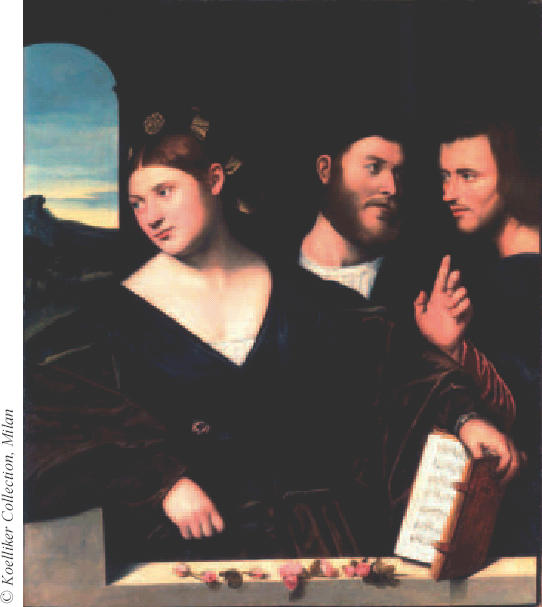

As in consultations, there are often shadowy figures in the background. Who is not, or had previously been, in the composition, is often fascinating. Alongside one painting is the painting of the head of another character who was not included in the final painting's story. The most interesting action may be in the corner of the frame and, for instance, involve, not the king bringing the gift to the infant Christ, but the interaction between two soldiers. In An allegory of love, by Bernardino Licinio, the main figure gazes out of the side of the frame. The main action appears to be somewhere else, often the perception gained in interactions with patients and a technique used to good effect by several contemporary photographers.The contrasting styles of different painters of the age are illustrated. Erotic themes were treated in a delicate and poetic manner by Titian. Later, Bordon, for instance, dealt with them in a more explicitly sensual way. Some painters have chosen muted colours, some, like Andrea Schiavone in the Infancy of Jupiter, have chosen glorious ones.

This beautiful exhibition gives satisfying and fascinating insight into the social, political and artistic context of the city state of Venice in the 15th and 16th centuries. It pulls together paintings from a wide range of sources, some never seen in public before. Go whenever you can, be the day dreich or otherwise …

Bernardino Licinio, Allegory of Love, c. 1520.

Footnotes

a Dreich = dreary.