Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is a sexually transmitted infection that is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis types L1, L2, and L3.1 Although endemic in some tropical countries, lymphogranuloma venereum is usually uncommon in the United Kingdom.1 The classical presentation of LGV is with genital ulceration (which may be asymptomatic or transient) and associated painful inguinal lymphadenopathy (or bubo), but it may also present with proctitis, extragenital lymphadenopathy, and systemic symptoms, including fever.1 Response to treatment of early infection is usually excellent. Untreated infection, however, can result in lymphatic obstruction and fibrosis, leading to genital elephantiasis, or, if involving the rectum, the formation of strictures and fistulas.

In January 2004, genitourinary doctors in Europe were alerted to the existence of a cluster of cases of lymphogranuloma venereum presenting as a rectal syndrome in men who have sex with men with HIV infection.2 We describe three cases of LGV for which diagnosis was considerably delayed because the possibility of this infection was not considered.

Case reports

Case 1

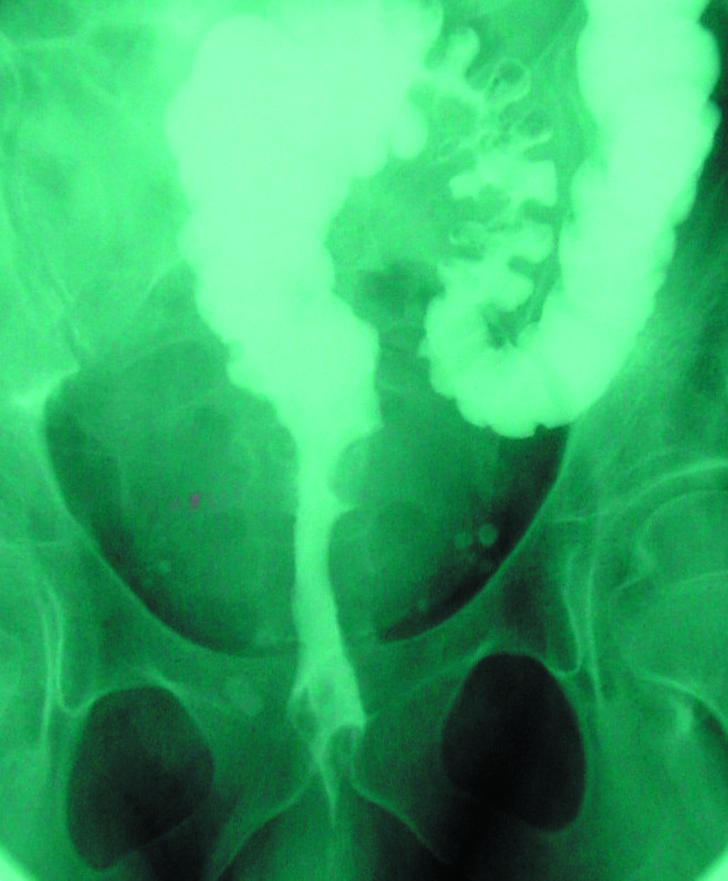

A 33 year old HIV positive man who has sex with men presented to his general practitioner in May 2003 with a short history of perianal pain accompanied by discomfort on sitting. His HIV disease was well controlled with antiretroviral therapy, and his CD4 lymphocyte count was 799 × 109/l. His symptoms persisted and he developed rectal bleeding accompanied by the passage of mucus, with alternating diarrhoea and constipation and lower abdominal discomfort. We referred him for investigation, and he had colonoscopy and biopsy, which showed an ulcerative proctitis with a fibrotic stricture 7 cm from the anal margin (figure). The histology of the biopsies was consistent with active ulcerative colitis, and he was treated with oral prednisolone and mesalazine. His symptoms failed to resolve: he developed constant overflow diarrhoea and faecal incontinence. He was examined under anaesthesia with repeat biopsies. Analysis of a rectal biopsy using a nucleic acid amplification test showed evidence of Chlamydia infection. The possible importance of this was not recognised. Surgical excision of the rectal stricture was planned, but in January 2005 we considered the possibility of LGV. Serology for Chlamydia using a whole inclusion immunofluorescence assay showed a titre of 1: > 4000 for antibody to C trachomatis serovar L2, and a complement fixation test for psittacosis/LGV showed a titre of 1:512, supporting the clinical diagnosis of LGV. We treated the man with 100 mg of doxycycline twice daily for six weeks, with some improvement in his tenesmus, rectal bleeding, and the passage of mucus. He is still likely to need surgical management of his rectal stricture.

Figure 1.

Water soluble enema showing rectal stricture with ulceration

Case 2

A 39 year old man who has sex with men and was HIV positive with a CD4 lymphocyte count of 492 × 109/l on no antiretroviral treatment presented to his general practitioner in October 2004 with diarrhoea followed by increasing constipation, faecal incontinence, and severe rectal pain. He also complained of the passage of blood and mucus from his rectum. His doctor referred him to hospital for further investigation. He had been diagnosed as having hepatitis C in April 2004. At colonoscopy, he had extensive rectal ulceration. Biopsies showed severe non-specific inflammation. He was referred to the genitourinary medicine clinic for screening for sexually transmitted causes of his symptoms. A rectal swab was positive for Chlamydia, which was confirmed as LGV. His symptoms improved rapidly with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for three weeks.

Case 3

A 37 year old man who has sex with men was seen by his general practitioner in August 2004. The patient had a history of diarrhoea one month before that date, but it had settled spontaneously. He had then developed increasing constipation with pain on defecation, associated with the passage of blood and mucus, and ribbon-like stools. He was referred for investigation and had a technically unsuccessful colonoscopy. In December 2004 he tested positive for HIV antibody at his general practitioner's surgery, as part of an insurance medical examination. While he was waiting for a repeat colonoscopy, he was admitted to hospital for drainage of a perianal abscess. At his first HIV outpatient visit he had a CD4 lymphocyte count of 1006 × 109/l. In view of his continuing rectal symptoms, the possibility of LGV was considered. A rectal swab was positive for Chlamydia, which was confirmed as LGV. We treated him with 100 mg of doxycycline twice daily for three weeks, and his symptoms resolved.

Discussion

In December 2003, a cluster of cases of LGV presenting with anorectal symptoms only, in men who have sex with men, was reported in Rotterdam, and subsequently cases have been reported in Paris, Antwerp, Stockholm, and Hamburg. Although no cases had been reported in the UK by October 2004, the Health Protection Agency set up increased surveillance for LGV.3 By 1 November 2005, 245 cases of LGV in men who have sex with men had been reported to the agency; eight of these were in patients who had presented before October 2004, and the diagnosis was made retrospectively on stored samples (Iona Martin, personal communication, 2005). Of cases reported to date in Europe, most have been in HIV positive men who have sex with men. Concomitant sexually transmitted infections were common, and a number of patients were found to have seroconverted recently for hepatitis C and HIV. Diagnostic delay was also common, as seen in all of the cases that we report here, as many doctors may be unfamiliar with the condition. Untreated LGV can cause severe pathology.1 In addition, ulcerative sexually transmitted diseases increase the transmission of HIV.4 For these reasons it is important that the diagnosis of LGV is considered in men presenting with anorectal symptoms; the symptoms of infection may be relatively minor in early infection. The diagnosis can be made by taking a rectal swab for Chlamydia, which should be processed using a nucleic acid amplification test. Positive samples can be confirmed using molecular techniques, by referring the sample to the Health Protection Agency.5 Serology for Chlamydia may also be of value, although it is less specific.1 Treatment with 100 mg of oral doxycycline twice daily for three weeks is effective.6 Infection with LGV has spread rapidly throughout Europe in the past 18 months,7 and increasing numbers of cases are likely to be seen in the UK. Awareness of this unusual infection among those to whom it is likely to present—that is, general practitioners, gastroenterologists, general physicians, and surgeons—is essential if patients are to be correctly diagnosed. Patients with confirmed or suspected LGV should be referred to genitourinary medicine clinics for management, including partner notification, and for screening for other sexually transmitted infections, particularly HIV, hepatitis C, and syphilis.

Editorial by Collins et al

Use a rectal swab to test men who have sex with men presenting with anorectal symptoms for Chlamydia

Contributors: Both authors cared for the patients and wrote and reviewed the manuscript. DC is guarantor.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Mabey D, Peeling RW. Lymphogranuloma venereum. Sex Transm Infect 2002;78: 90-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gotz H, Nieuwenheis R, Ossewaarde T, Bing Thio H, Van der Meijden W, Dees J, et al. Preliminary report of an outbreak of lymphogranuloma venereum in homosexual men in the Netherlands, with implications for other countries in Western Europe. Eurosurveillance Weekly 2004;8. www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2004/040122.asp (accessed 9 Sep 2005).

- 3.Enhanced surveillance of lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) in England. CDR Weekly 2004;14: 3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galvin SR, Cohen MS. The role of sexually transmitted diseases in HIV transmission. Nat Rev Microbiol 2004;2: 33-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Health Protection Agency. LGV (lymphogranuloma venereum). London: HPA. www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/hiv_and_sti/LGV/lgv.htm (accessed 9 Sep 2005).

- 6.British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. Clinical effectiveness guidelines. London: Royal Society of Medicine. www.bashh.org/guidelines/ceguidelines.htm (accessed 13 April 2005).

- 7.Simms I, Macdonald N, Ison C, Martin I, Alexander S, Lowndes C, et al. Enhanced surveillance of lymphogranuloma (LGV) begins in the UK. Eurosurveillance Weekly 2004;8. www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2004/041007.asp#4 (accessed 9 Sep 2005).