Abstract

Resistance of Helicobacter pylori to clarithromycin occurs with a prevalence ranging from 0 to 15%. This has an important clinical impact on dual and triple therapies, in which clarithromycin seems to be the better choice to achieve H. pylori eradication. In order to evaluate the possibility of new mechanisms of clarithromycin resistance, a PCR assay that amplified a portion of 23S rRNA from H. pylori isolates was used. Gastric tissue biopsy specimens from 230 consecutive patients were cultured for H. pylori isolation. Eighty-six gastric biopsy specimens yielded H. pylori-positive results, and among these 12 isolates were clarithromycin resistant. The latter were studied to detect mutations in the 23S rRNA gene. Sequence analysis of the 1,143-bp PCR product (portion of the 23S rRNA gene) did not reveal mutation such as that described at position 2142 to 2143. On the contrary, our findings show, for seven isolates, a T-to-C transition at position 2717. This mutation conferred a low level of resistance, equivalent to the MIC for the isolates, selected using the E-test as well as using the agar dilution method: 1 μg/ml. Moreover, T2717C transition is located in a highly conserved region of the 23S RNA associated with functional sites: domain VI. This fact has a strong effect on the secondary structure of the 23S RNA and on its interaction with macrolide. Mutation at position 2717 also generated an HhaI restriction site; therefore, restriction analysis of the PCR product also permits a rapid detection of resistant isolates.

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative rod involved in gastric diseases such as gastritis, peptic ulcer, and gastric carcinoma (21, 26). The National Institutes of Health in the United States, the Maastricht Consensus in Europe, and the Canadian Consensus recommend treatment of these digestive diseases with antibiotics (21). Therapies, including two antimicrobials (clarithromycin plus amoxicillin or metronidazole) plus a proton pump inhibitor, are currently used [7, 14, 25; R. Cayla, F. Zerbib, P. Talbi, F. Mégraud, and H. Lamouliatte, abstract, Gut 37(Suppl. 1):A55, 1995]. Although H. pylori is susceptible to most antimicrobial agents in vitro, in vivo eradication of this pathogen has been difficult (13-16, 25). The increased prevalence of antibiotic-resistant H. pylori strains has serious implications as, apart from patient compliance, antimicrobial resistance is the most important factor determining the outcome of antibiotic treatment. A large number of studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of H. pylori resistance in various countries ranges from 10 to 90% for metronidazole and from 0 to 15% for clarithromycin (3, 25) Resistance against clarithromycin and metronidazole is also frequently associated and is of particular clinical importance as these drugs are used in almost all standard H. pylori eradication regimens (15, 16). Particularly, the development of clarithromycin resistance among H. pylori strains, has become a predominant cause of failure of therapy including this drug (2, 15, 16, 25, 31). Until today most findings show that the main mechanism responsible for clarithromycin resistance is a mutation such as an adenine-to-guanine transition at either position 2143 or an adenine-to-cytosine transversion at position 2143 of 23S rRNA [1, 22, 24; Cayla et al., Gut 37(Suppl. 1):A55, 1995]. The mechanism of resistance to clarithromycin in H. pylori seems to be a decrease in binding of macrolide to ribosome associated with point mutations of the 23S rRNA gene (5). In the present study we have examined the DNA sequences of the 23S rRNA genes from 12 H. pylori clinical isolates. In spite of clarithromycin resistance exhibited in vitro by our strains (MIC ≥ 1 μg/ml) the sequence analysis of 23S rRNA did not confirm these data. No mutations were found at positions 2142 and 2143. The aim of our work was to look for other sites or single mutation points which could be associated with clarithromycin resistance of our clinical isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

A total of 230 adult patients (median age, 45 years; range 22 to 68 years) presenting upper gastrointestinal symptoms were enrolled in the study, and all patients gave informed consent. Most patients had not been submitted to eradication therapy in the previous 3 months. The only exceptions were 21 subjects who referred to previous eradication therapy, which, for 12 of them, included clarithromycin.

All patients enrolled in the study underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Three biopsy specimens for each patient, taken from the antrum, the gastric body, and the duodenal mucosa using a disinfected endoscope, were placed in 0.1 ml of sterile saline solution and sent to the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory of the University of Rome “Tor Vergata.” Samples were microbiologically processed within 3 h. A rapid test for the detection of urease activity was performed on biopsy samples (8, 17). Eighty-six H. pylori isolates from different patients were obtained by culturing the biopsy specimens. Among the isolates, 12 H. pylori strains determined to be clarithromycin resistant were studied.

Bacteria and culture conditions.

Biopsy samples were cultured on H. pylori selective medium Dent agar plates (Oxoid Ltd., London, England) supplemented with 7% fresh horse blood. Plates were incubated at 37°C in a microaerobic atmosphere and 98% humidity for 7 to 14 days for primary culture. Every 2 to 3 days isolates were subcultured in nonselective medium such as brain heart infusion agar containing 7% defibrinated horse blood (28). Strains were identified according to colony morphology, Gram stain, urease, catalase, oxidase, and biochemical properties, which were studied by using API CAMPY (bioMérieux, Les Balmas, France) (11, 17).

In the study a strain from the American Type Culture Collection, namely, H. pylori ATCC 43504, was also employed. The isolates, as well as the standard reference strains, were stored at 80°C in 0.5 ml of defibrinated horse blood.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities and natural transformation.

E-test (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) determinations of MICs were performed on Mueller-Hinton agar plates (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) supplemented with 5% sheep blood. A sterile swab was dipped into a bacterial suspension equivalent to a no. 2 McFarland standard. After swabbing the entire plate surface with inoculum, sterile E-test strips, impregnated with clarithromycin ranging in concentration from 0.016 to 256 μg/ml, were placed on the agar surface (12, 29). Plates were incubated at 37°C under microaerobic conditions and 98% humidity for 3 to 4 days. MICs were determined as described by Glupczynski et al. (10). Isolates were classified as clarithromycin resistant if the MIC exceeded 1 μg/ml (19, 20).

As suggested by Osato et al., strains determined to be clarithromycin resistant were confirmed by the agar dilution procedure approved methodology recommended by the NCCLS (20, 23). Isolates were classified as clarithromycin resistant if the MIC exceeded 1 μg/ml [19, 20; Cayla et al., Gut 37(Suppl. 1):A55, 1995]. A susceptible quality control reference strain, H. pylori ATCC 43504, as well as the susceptible isolate H. pylori−CS were used throughout the testing.

Introduction of the clarithromycin-resistant determinants into a susceptible strain by natural transformation was performed on a BHI-YE agar surface as described by Taylor et al. (24). Briefly, recipient cells were heavily inoculated onto cold BHI-YE agar plates and were grown for 4 to 10 h; this was followed by the addition of 0.5 to 1 μg of donor DNA to the bacterial lawn (that is, the PCR fragment containing the site-specific mutation of 1,143 bp). Subsequently, the cells grew for 3 days, and Clar transformants were selected on BHI-YE agar plates containing clarithromycin at 0.5 and 1 μg/ml (kindly provided by Claudio Grandi from Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, Ill.).

Bacterial lysate preparations.

Bacteria were cultivated on nonselective medium until confluent growth had been reached. Cells, collected from the surface of a plate cultured for 3 days, were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline solution and centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 × g. The supernatant was then discarded, and 300 μl of extraction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.5% Tween 20) was added to the pellet. The pellet was resuspended, and 7.5 μl of proteinase K solution (10 mg/ml) was added. The mixture was incubated for 1 h at 60°C. Finally, the proteinase was inactivated by heating the samples at 98°C for 10 min (18). Ten microliters of supernatant from these crude lysates was added to each PCR amplification reaction mixture. A positive control for the PCR assay, a crude lysate of H. pylori ATCC 43504, prepared following the same procedure described for the isolates, was routinely used in each PCR assay. As a reference control for the susceptible strains we chose one of the susceptible isolates for which the MIC was 0.016 μg/ml (H. pylori−CS).

Detection of mutations.

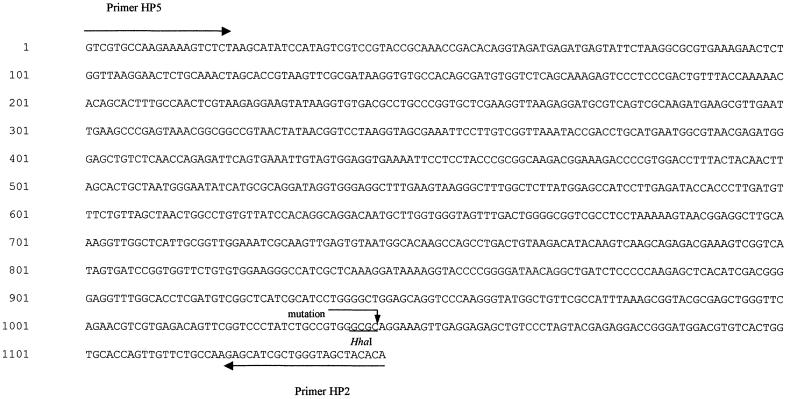

Mutations were identified by PCR amplification methods of a portion of 23S rRNA and subsequent nucleotide sequencing of the 1,143-bp PCR product. The PCR amplifications, using crude lysates, were performed with primers derived from a known sequence of the 23S rRNA gene: Hp5 forward, 5′-GTC-GTG-CCA-AGA-AAA-GCG-TCT-3′ (positions 1672 to 1693; GenBank accession number U27270), and Hp2 reverse, 5′-TGT-GTG-CTA-CCC-AGC-GAT-GCT-C-3′ (positions 2811 to 2790; GenBank accession number U27270). PCR product resulted in 1,143 bp. Amplification reaction mixtures (50 μl) contained 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 9.0), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl, 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.), 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 50 pmol of each primer, and 10 μl of crude bacterial lysate. Amplification was carried out in a DNA thermal cycler (model 9700; Perkin-Elmer Corporation, Norwalk, Conn.). Thirty cycles, each 45 s at 95°C, 30 s at 58°C, and 1 min at 72°C, were performed after 2 min of denaturation at 95°C. Cycles were followed by a final elongation at 72°C for 4 min. Ten-microliter portions of the PCR products were then analyzed by electrophoresis within a 1.5% agarose gel in Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) buffer stained with ethidium bromide in parallel with a molecular weight marker: Gene ruler 100-bp DNA ladder (MBI Fermentas; Vilnius, Lithuania). The PCR product was purified by spin column QIAQuick (QIAGEN, GmbH, Germany) and cycle sequenced by using the ABI PRISM Big Dye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, Calif.).

In the sequencing primers Hp-5, Hp-2, and an internal primer, Hp-3 (5′-CGC-GGC-AAG-ACG-GAA-AG-3′) (positions 2130 to 2150; GenBank accession number U27270) and Hp-1 (5′-CCA-CAG-CGA-TGT-GGT-CTC-AG-3′) (positions 1820 to 1840; GenBank accession number U27270) were used. DNA sequences were carried out by using an automatic sequencer, ABI PRISM 310, version 3.4.1 (Applied Biosystem). The resulting nucleotide sequence of the 1,143-bp region of the 23S rRNA gene was aligned using the Sequence Navigator software package (Applied Biosystem).

Restricion analysis of PCR products.

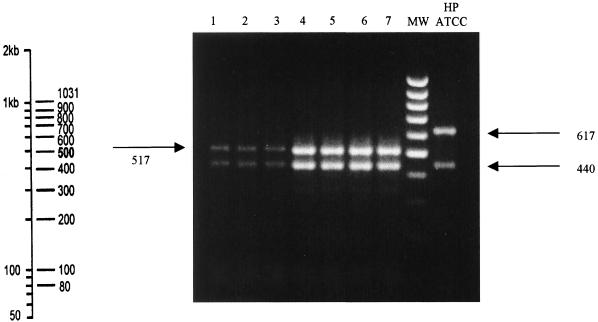

For rapid detection of the T2717C mutation, 5 U of HhaI (Amersham Pharmacia) was added to 10 μl of each amplicon and digestion was performed at 37°C for 2 h, as recommended by the manufacturer. Digested PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, in TAE buffer.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial susceptibility.

Of the 86 H. pylori isolates, 74 strains were susceptible to clarithromycin (MIC, 0.016 to 0.125 μg/ml), and the remaining 12 were resistant to clarithromycin. Among these resistant strains, five presented a high level of resistance (MIC, 32 to 256 μg/ml), while seven isolates showed a low level of clarithromycin resistance, being inhibited by clarithromycin at 1 μg/ml. No differences in MICs were found for all the resistant strains when these were tested by E-test as well as by the agar dilution method reported by Osato et al., who affirm that both methods can reliably determine clarithromycin resistance (23).

PCR amplification of 23S rRNA and sequence analysis.

Primers Hp-5 and Hp-2, designed to amplify 23S rRNA fragment from H. pylori, yielded a 1,143-bp PCR product. Amplicons were obtained for all the 86 H. pylori isolates examined.

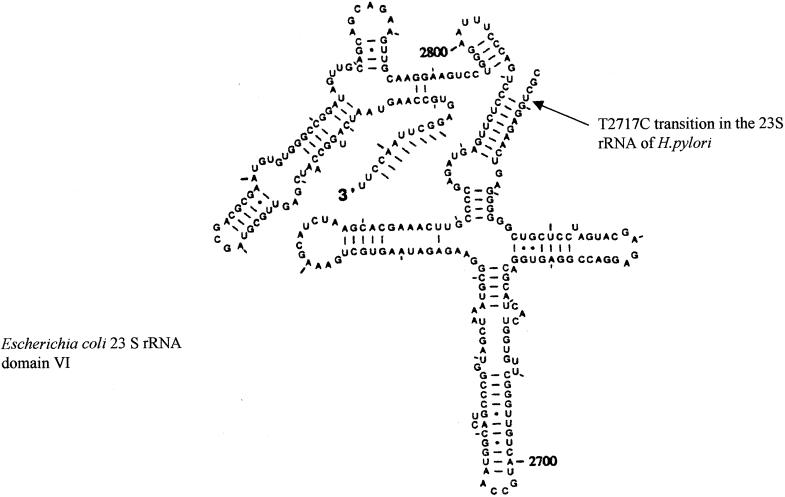

To examine the genetic basis of these resistant phenotypes, we analyzed the nucleotide sequence, for all the resistant isolates, of the 1,143-bp PCR product of the 23S rRNA gene, and we compared these sequences with those obtained for the standard reference strain (H. pylori ATCC 43504) as well as with that of the susceptible isolate, namely, H. pylori−CS. None of the our isolates showed the mutation described at positions 2142 and 2143 (4, 29). Particularly, the sequence analysis of seven resistant isolates, showing a low level of clarithromycin resistance (MIC = 1 μg/ml), presented a single mutation point: the transversion of T to C at position 2717. In Fig. 1 the nucleotide sequence of one low-level-resistant strain is reported, while in Fig. 2 was indicated by an arrow the position of T2717C mutation in the model of the 23S rRNA domain VI (6).

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence of the 1,143-bp amplicon from the 23S rRNA gene from an H. pylori-resistant isolate. The arrow indicates a single point mutation, that is, a T2717C transition. The underline indicates the HhaI restriction site position. Arrows from the 5′ to 3′ termini indicate primer sequences.

FIG. 2.

Model of domain VI of 23S rRNA from E. coli, reproduced from reference 6 with permission. An arrow indicates the position of the low-level Clar determinant in H. pylori consisting of a T2717C transition.

The remaining five isolates, for which the MICs ranged from 32 to 256 μg/ml, did not present T2717C transition.

Apart from nucleotide sequence analysis, resistant strains could also be easily differentiated from susceptible ones using HhaI restriction analysis. The presence of a T2717C mutation creates four HhaI restriction sites in the 23S rRNA gene amplicon and yields digestion products of 86, 440, 517, and 100 bp. The absence of such mutation in the susceptible isolates (that at position 2717) causes the absence of one restriction site. Therefore, the amplicons, obtained from the susceptible isolate, were only digested into three bands of 86, 440, and 617 bp, respectively. Figure 3 illustrates the digestion pattern of the amplicons obtained from our resistant strains compared with that of standard reference strains H. pylori ATCC 43504. Fragments of 86 and 440 bp are equally present in amplicon from resistant as well as susceptible isolates, so they are not useful in distinguishing the mutation, while the different migration of 517- or 617-bp fragments are easily distinguishable. The 100-bp fragment, present only in mutated amplicon, comigrates with the 86-bp fragment and is therefore unhelpful in recognizing resistant strains.

FIG. 3.

HhaI restriction analysis of 1,143-bp amplicons from 23S RNA gene. Lanes 1 to 7, the digestion products of seven Clar isolates showing two fragments, respectively, of 440 and 517 bp. Lane HP ATCC, with two clearly distinguishable bands of 440 and 617 bp, corresponds to restriction analysis of the susceptible isolates. Lane MW, molecular weight marker 100-bp DNA ladder, whose fragment size has been reported on the left of the figure.

The sequence analysis of the five remaining strains exhibiting a high level of resistance shows neither the mutation described at positions 2142 and 2143 nor our mutation [4, 28; J. Versalovic, M. Osato, K. Spakovsky, M. P. Dore, R. Reddy, G. G. Stone, D. Shortridge, R. K. Flamm, and S. K. Tanaka, abstract, Gut 39(Suppl. 2):A9, 1996].

Natural transformation.

A PCR fragment of 1,143 bp from Clar strains was used to transform H. pylori−CS. Clar H. pylori−CS transformants were selected on BHI-YE agar supplemented with 0.5 and 1 μg of clarithromycin per ml. Single colonies, from three obtained, were used for MIC testing, and it was found that the MIC of clarithromycin was the same for the transformants. The relevant mutation (T2717C) in transformants was confirmed by DNA sequencing to be the same as that in the donor strains. Subculturing of the colonies, Clar phenotypes of these clones were shown to be stable. This suggests that the mutation was incorporated into chromosome.

DISCUSSION

Early studies of the genomic physical and genetic maps of various H. pylori strains have demonstrated that H. pylori clarithromycin resistance is associated to a common single mutation point [28, 29; Versalovic et al., Gut 39(Suppl. 2):A9, 1996]. This mutation most frequently affects positions A2058 and A2059 in Escherichia coli and A2142 or A2143 in H. pylori [9, 28, 29; Stone, G. G., D. Shortridge, R. K. Flamm, J. Versalovic, J. Beyer, A. T. Ghoneim, D. Y. Graham, and S. K. Tanaka, abstract, Gut 39(Suppl. 2):A9, 1996; Versalovic et al.]. Particularly, mutation at position 2143 is usually associated with H. pylori phenotype expressing different levels of resistance, MIC ranged from 2 to 256 μg/ml, while strains with mutation at position 2142 frequently exhibited a MIC ≥ 64 μg/ml.

On the contrary, our resistant strains, on the basis of their clarithromycin susceptibility, can be divided into two groups showing different phenotypes and genotypes.

The first group is composed of seven low-level-resistant strains (MIC, 0.5 to 1 μg/ml) which do not show mutations at position 2142 or 2143 but that present a new mutation point, never described before. This mutation is the transition T2717C.

The second group is composed of strains exhibiting a high level of resistance (MIC ≥ 64 μg/ml), which presents neither mutations such as A2142G and A2143C nor the mutation described herein. This fact is not surprising, as other researchers have also reported that for some H. pylori strains, the mechanism of resistance remains undetermined (29). Further studies considering other possible, albeit unusual, mechanisms of resistance will be planned to investigate these five strains. It is relevant to note that the seven low-level-resistant strains were cultured from gastric biopsy specimens from different patients who had previously received a therapy including clarithromycin. This is in agreement with reports from other authors, who also affirm that resistance to this drug occurs frequently during therapy and this is the predominant reason for therapy failure (4). This evidence—in addition to the facts that (i) the isolates present a single point mutation at position 2717, which is not present in the susceptible strain nor in other high-level-resistant strains; (ii) the MICs for natural transformant clones, obtained by introducing Clar determinants from the donor Clar H. pylori isolates into the Clas strain H. pylori−CS, were the same MICs as those for as resistant strains and these transformants had acquired the same mutation (T2717C) as the resistant strains; and (iii) the T2717C transition, which falls in a highly conserved region of the 23S rRNA associated with functional sites, domain VI (which is the elongation factor binding site), has a strong effect on the secondary structure of the 23S RNA and with its interaction with macrolide (30)—suggests that the T-to-C transition at position 2717 may be responsible for clarithromycin resistance.

Particularly the HhaI restriction analysis of the amplified products and subsequent sequencing analysis allowed a rapid screening of the isolates. The rapid detection of the presence, or absence, of resistance markers could help to direct the treatment regimen for the patient, avoiding treatment failure.

In conclusion, our findings not only confirm the usefulness of testing the isolates for susceptibility, in order to reduce therapeutic failure, but also underline the importance of continuing to study the genetic relationship between any single point mutation and drug resistance (27). This is particularly true and helpful for those strains not categorized in a previously known and worldwide genotype (but which can be relatively common in some small countries). We therefore propose a further molecular analysis of macrolide resistant H. pylori. We are, in fact, studying other strains of H. pylori, showing lower sensibility to clarithromycin (MIC, 0.25 to 0.5 μg/ml), for which until now it has not been possible to clearly associate a mutation with a particular phenotype of susceptibility.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the excellent technical collaboration of Francesca Capalbo, Enrico Salvatore Pistoia, and Daniele Marino. We are grateful to Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, Ill., for donating the clarithromycin powder. We thank A. Inglis for her helpful linguistic revision of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grant Cofinanziamento 1999 entitled Dispepsia ed Helicobacter pylori: identificazione di pazienti ad alto rischio per lo sviluppo di ulcera peptica from M.U.R.S.T.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alarcon, T., D. Domingo, N. Prieto, and M. Lopez-Brea. 2000. PCR using 3′-mismatched primer to detect A2142 C mutation in 23S rRNA conferring resistance to clarithromycin in Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:923-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burucoa, A., V. Lhomme, and J. L. Fauchere. 1999. Performance criteria of DNA fingerprinting methods for typing of Helicobacter pylori isolates: experimental results and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:4071-4080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Debets-Ossenkopp, Y. J., A. J. Herscheid, R. G. Pot., E. J. Kuipers, J. G. Kusters, and C. M. Vandenbroucke-Grauls. 1999. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori resistance to metronidazole, clarithromycin, amoxycillin, tetracycline and trovafloxacin in the Netherlands. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43:511-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debets-Ossenkopp, Y. J., M. Sparrius, J. G. Kusters, J. J. Kolkmann, and C. M. J. E. Vandenbroucke-Grauls. 1996. Mechanism of clarithromycin resistance in clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 142:37-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doi, R. H. 1991. Regulation of gene expression. p. 15-39. In U. N. Streips and R. E. Yasbin (ed.), Modern microbial genetics. Wiley-Liss, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 6.Egebjerg, J., N. Larsen, and R. A. Garret. 1990. Structural map of 23S rRNA, p. 168-179. In W. E. Hill, A. Dahlberg, R. A. Garrett, P. B. Moore, D. Schleissinger, and J. R. Warner (ed.), The ribosome: structure, function and evolution. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 7.European Helicobacter pylori Study Group. 1997. Current European concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut 41:8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fontana, C., A. Pietroiusti, A. Mastino, E. S. Pistoia, D. Marino, A. Magrini, A. Galante, and C. Favalli. 2000. Comparison of an enzyme immunoassay versus a rapid latex test for serodiagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:239-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujimura, S. 2000. Clarithromycin-susceptible Helicobacter pylori with mutation in 23S rRNA gene by PCR-RFLP method. J. Gastroenterol 35:315-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Arata, M. I., F. Baquero, L. De Rafael, C. M. De Argila, J. P. Gisbert, F. Bermejo, D. Boixeda, and R. Cantòn. 1999. Mutations in 23S rRNA in Helicobacter pylori conferring resistance to erythromycin do not always confer resistance to clarithromycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:374-376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Germani, Y., C. Dauga, P. Duval, M. Huerre, M. Levy, G. Pialoux, P. Sansonetti, and P. A. D. Grimont. 1997. Strategy for the detection of Helicobacter pylori species by amplification of 16S rRNA genes and identification of H. felis in human gastric biopsy. Res. Microbiol. 148:315-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glupczynski, Y., M. Labbè, W. Hansen, F. Crokaert, and E. Yourassowsky. 1991. Evaluation of the E-test for quantitative antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Helicobacter pylori. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:2072-2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goddard, A. F., and R. P. H. Logan. 1996. Antimicrobial resistance and Helicobacter pylori. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 37:639-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham, D. Y., W. A. de Boer, and J. T. Tytgat. 1996. Choosing the best anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy: effect of antimicrobial resistance. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 91:1072-1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuster, J. G., and and E. J. Kuipeers. 2001. Antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori. Symp. Ser. Soc. Appl. Microbiol. 30:134S-144S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Logan, R. P. H., P. A. Gummett, H. D. Schaufelberger, R. R. F. H. Greaves, G. M. Mendelson, and M. M. Walker. 1994. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori with clarithromycin and omoprazole. Gut 35:323-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mirza, S. H., A. Hannan, and F. Rizvi. 1993. Helicobacter pylori: isolation from gastric biopsy specimens. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 87:483-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monteiro, L., J. Cabrita, and F. Mégraud. 1997. Evaluation of performances of three DNA enzyme immunoassays for detection of Helicobacter pylori PCR products from biopsy specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2931-2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility test for bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed.; approved standard M7-A3. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 20.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1999. Performance standard antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 5th informational supplement. M100S9. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 21.NIH Consensus Conference. 1994. Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease. JAMA 272:65-69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Occhialini, A., M. Urdaci, F. Doucet-Populaire, C. M. Bebear, H. Lamouliatte, and F. Mégraud. 1997. Macrolide resistance in Helicobacter pylori: rapid detection of point mutations and assays of macrolide binding to ribosome. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2724-2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osato, M. S. R. Reddy, S. G. Reddy, R. L. Penland, and D. Y. Graham. 2001. Comparison of the E-test and the NCCLS-approved agar dilution method to detect metronidazole and clarithromycin resistant Helicobacter pylori. Intern. J. Antimicrob. Agents 17:39-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor, D. E., G. Zhongming, D. Purych, T. Lo, and K. Hiratsuka. 1997. Cloning and sequence analysis of two copies of the 23S rRNA gene from Helicobacter pylori and association of clarithromycin resistance with 23S rRNA mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2621-2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torracchio, S., L. Cellini, E. Di Campli, G. Cappello, M. G. Malatesta, A. Ferri, A. F. Ciccaglione, L. Grossi, and L. Marzio. 2000. Role of antimicrobial susceptibility testing on efficacy of triple therapy in Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 14:1639-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaira, D., J. Holton, M. Miglioli, M. Menegatti, P. Mule, and L. Barbara. 1994. Peptic ulcer disease and Helicobacter pylori infection. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 10:98-104. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Der Ende, A., L. J. Van Doorn, S. Rooijakkers, M. Feller, G. N. Tytgat, and J. Dankert. 2001. Clarithromycin-susceptible and -resistant Helicobacter pylori isolates with identical randomly amplified polymorphic DNA-PCR genotypes cultured from single gastric biopsy specimens prior to antibiotic therapy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2647-2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Versalovic, D. Shortridge, K. Kimbler, M. V. Griffy, J. Beyer, R. K. Flamm, S. K. Tanaka, D. Y. Graham, and M. F. Go. 1996. Mutations in 23S rRNA are associated with clarithromycin resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:477-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Versalovic, J., M. S. Osato, K. Spakovsky, M. P. Dore, R. Reddy, G. G. Stone, D. Shortridge, R. K. Flamm, S. K. Tanaka, and D. Y. Graham. 1997. Point mutations in the 23S rRNA gene of Helicobacter pylori associated with different levels of clarithromycin resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:283-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vester, B., and S. Douhwaite. 2001. Macrolide resistance conferred by base substitutions in the 23S rRNA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, G., and D. Taylor. 1998. Site-specific mutations in the 23S rRNA gene of Helicobacter pylori confer two types of resistance to Macrolide-lincosamide-Streptogramin B Antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1952-1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]