Abstract

The antiviral efficacies and cytotoxicities of 2′,3′- and 4′-substituted 2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxycytidine analogs were evaluated. All compounds were tested (i) against a wild-type human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) isolate (strain xxBRU) and lamivudine-resistant HIV-1 isolates, (ii) for their abilities to inhibit hepatitis B virus (HBV) production in the inducible HepAD38 cell line, and (iii) for their abilities to inhibit bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) production in acutely infected Madin-Darby bovine kidney cells. Some compounds demonstrated potent antiviral activities against the wild-type HIV-1 strain (range of 90% effective concentrations [EC90s], 0.14 to 5.2 μM), but marked increases in EC90s were noted when the compounds were tested against the lamivudine-resistant HIV-1 strain (range of EC90s, 53 to >100 μM). The β-l-enantiomers of both classes of compounds were more potent than the corresponding β-d-enantiomers. None of the compounds showed antiviral activity in the assay that determined their abilities to inhibit BVDV, while two compounds inhibited HBV production in HepAD38 cells (EC90, 0.25 μM). The compounds were essentially noncytotoxic in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and HepG2 cells. No effect on mitochondrial DNA levels was observed after a 7-day incubation with the nucleoside analogs at 10 μM. These studies demonstrate that (i) modification of the sugar ring of cytosine nucleoside analogs with a 4′-thia instead of an oxygen results in compounds with the ability to potently inhibit wild-type HIV-1 but with reduced potency against lamivudine-resistant virus and (ii) the antiviral activity of β-d-2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxy-5-fluorocytidine against wild-type HIV-1 (EC90, 0.08 μM) and lamivudine-resistant HIV-1 (EC90 = 0.15 μM) is markedly reduced by introduction of a 3′-fluorine in the sugar (EC90s of compound 2a, 37.5 and 494 μM, respectively).

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is a retrovirus belonging to the family Lentiviridae, while hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the prototype member of the family Hepadnaviridae. A characteristic feature common to both families is that they replicate over a RNA-cDNA intermediate through the virally encoded reverse transcriptase (RT) enzyme, although the mechanisms are different. In order to control the course of the disease in infected individuals, highly active antiretroviral therapies are commonly prescribed. At present, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved for use seven nucleoside analogs that target the HIV-1 RT, and one of these nucleoside analogues, lamivudine (Epivir), is also approved for use against HBV. However, due to the ongoing replication of the virus, antiviral drug resistance develops, eventually leading to the failure of therapy (15, 22). Therefore, there is a continuing need for more potent anti-HIV-1 and anti-HBV drugs.

Mitochondrial toxicity is clearly recognized as an adverse effect of the long-term use of highly active antiretroviral therapies and, in particular, certain nucleoside RT inhibitors (3, 8). The clinical features of this mitochondrial toxicity vary depending on the tissues that are affected and are largely dependent on the aerobic metabolism needed for the energy supply required for that particular tissue. Most toxic events are reversible at an early stage; however, lactic acidosis is often irreversible and in severe cases can result in death (7, 18). Since the mitochondrial dysfunction develops over months and symptoms are initially mild, it is important to develop sensitive cell-based assays that allow determination of the enzyme activity and inhibition by the selected antiviral agent. Equally important, new candidate antiviral agents need to be evaluated for their unfavorable DNA polymerase γ-inhibiting capacities in human cells.

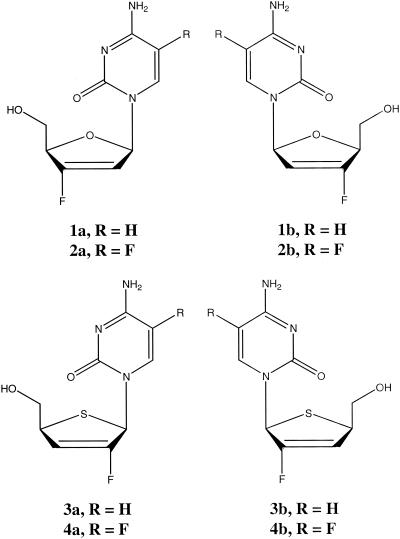

In the search for antiviral compounds related to β-d-2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxy-5-fluorocytidine (d-D4FC; Reverset), a drug that is in clinical trials (24), two related new classes of nucleoside compounds, namely, 2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxy-2′-fluoro-4′-thiacytidine and modified 2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-fluorocytidine were synthesized in the d and l configurations and evaluated for their antiviral activities (Fig. 1). The rationale for the synthesis was to acid stabilize the glycosidic bond. To rank the antiviral potencies, three quantitative PCR assays were designed (Taqman 7700 chemistry; PE Applied BioSystems): one for HIV-1 genotype B (quantitative RT-PCR [Q-RT-PCR]) and one for HBV (quantitative PCR [Q-PCR]), which were designed essentially as described previously (21), and one for bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) (Q-RT-PCR). BVDV is often used as a model for hepatitis C virus (14, 19). The Q-RT-PCR results for HIV-1 were compared with those of a previously established cell-based antiviral drug evaluation assay (an assay for endogenous HIV-1 RT polymerization activity in cell supernatant) (23). Finally, the Q-PCR technology was also used to evaluate potential mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ inhibition related to treatment with these new compounds in relevant human cells.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of the nucleoside analogues evaluated in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds.

Eight compounds belonging to two structurally different groups with (i) variations on the d4-2′-F-4′-S-C motif and (ii) variations on the d4-3′-F-C motif were synthesized (Fig. 1). For both of these motifs, d- and l-enantiomers were tested, as was the 5-fluoro modification in the cytosine base. The synthesis of the compounds will be described elsewhere (C. K. Chu et al., unpublished data). As control compounds, 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine (AZT; zidovudine), lamivudine [(−)-β-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine; 3TC)], β-d-2′,3′-dideoxycytidine (d-ddC), ribavirin (1-β-d-ribofuranosyl-1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide), (+)-β-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine [(+)-BCH-189], 1-(2-deoxy-2-fluoro-1-β-d-arabinofuranosyl)-5-iodocytosine (FIAU; fialuridine), β-d-2′,3′-didehydro-3′-deoxythymidine (d4T), 9-(2-hydroxyethoxymethyl)guanine, and d-D4FC were included in the experiments described here.

HIV-1 cell culture.

Human peripheral blood mononuclear (PBM) cells (107 cells/T25 flask) were stimulated with phytohemagglutinin for 2 or 3 days and infected with either a wild-type HIV-1 strain (strain LAI or xxBRU) or a lamivudine-resistant HIV-1 strain (strain xxBRU-184V) at 100 50% tissue culture infective doses, as described previously (23). The culture was kept for 5 days in the presence of test compounds at serial 1-log dilutions. Subsequently, human PBM cells were removed from the culture supernatant by centrifugation (400 × g, 10 min, 4°C). This clarified supernatant was tested by either the RT assay or the Q-RT-PCR assay.

HIV-1 RT assay.

The virus particles present in a 1-ml aliquot of culture supernatant were concentrated by high-speed centrifugation (20,000 × g, 2 h, 4°C). The supernatant was then removed and the virus pellet was dissolved in 100 μl of virus solubilization buffer (0.5% Triton X-100, 0.8 M NaCl, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20% glycerol, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8]). A 10-μl aliquot of virus solubilization buffer was mixed with 75 μl of RT cocktail [60 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 12 mM MgCl2, 6 mM dithiothreitol, 6 μg of poly(rA)n-oligo(dT)10-12 per ml, 1.2 mM dATP, 80 μCi of [3H]TTP per ml] and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Subsequently, 100 μl of 10% trichloroacetic acid was added, and the total amount of [3H]TTP incorporated was determined.

HIV-1 Q-RT-PCR assay with human PBM cells.

The viral RNA present in the culture supernatant was prepared by using commercially available columns (QIAamp viral RNA mini kit; Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). Five microliters of viral RNA was detected by real-time RT-PCR (Q-RT-PCR; TaqMan 7700 chemistry; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The TaqMan probe and primers were designed by using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems); they covered conserved sequences complementary to an 81-bp fragment from the HIV-1 RT gene between codons 230 and 257 of the group M HIV-1 genome (sense primer, 5′-TGGGTTATGAACTCCATCCTGAT-3′; probe, 5′-6-carboxyfluorescein [6-FAM]-TTTCTGGCAGCACTATAGGCTGTACTGTCCATT-6-carboxytetra-methylrhodamine [TAMRA]-3′; antisense primer, 5′-TGTCATTGACAGTCCAGCGTCT-3′). This Q-RT-PCR protocol was linear over 6 log units of virus dilution (data not shown).

HBV Q-PCR assay with HepAD38 cells.

The HepAD38 cell line replicates HBV under conditions that can be regulated with tetracycline (11, 13). In the presence of this drug, the cell supernatant is virtually free of viral DNA, but upon the removal of tetracycline from the culture medium, these cells secrete HBV-like particles into the supernatant (11). HepAD38 cells were seeded at 5 × 104 cells/well in a 96-well plate in seeding medium (Dulbecco's minimal essential medium and F12 medium [DMEM-F12] plus 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 50 μg of kanamycin per ml, 400 μg of G418 per ml, 0.3 μg of tetracycline per ml) and incubated for 2 days at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humid atmosphere. The seeding medium was removed and the cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline. The cells were then incubated with 200 μl of assay medium (DMEM-F12, 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 IU of penicillin per ml, 10 μg of streptomycin per ml, 50 μg of kanamycin per ml) containing no compound, test compound, or control drugs at concentrations of 10 μM. After a 5-day incubation, the cell supernatant was collected and stored at −70°C until the HBV DNA was quantified. HBV DNA was extracted from the supernatant with QiaAmp DNA. The TaqMan probe and primers were designed by using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems); their sequences cover highly conserved sequences complementary to the DNA sequences present in HBsAg (21). A total of 5 μl of DNA was amplified by using the reagents and conditions described by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems). The standard curve showed a dynamic range of at least 6 log units (data not shown).

BVDV Q-RT-PCR assay with MDBK cells.

Madin-Darby bovine kidney (MDBK) cells were maintained in DMEM-F12 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated horse serum at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. The cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 5 × 103 cells/well and incubated for 1 h. BVDV (strain NADL) was used to infect the cells in a monolayer at a multiplicity of infection of 0.02. After 45 min of infection, the viral inoculum was removed and the cells were washed twice. Medium containing test compounds (or no drug as a control) was added to these cells, followed by 24 h of incubation. The cell supernatants were collected and clarified by centrifugation (3,000 × g, 2 min, room temperature), and viral RNA was prepared (QIAamp Viral RNA mini kit; Qiagen). Viral RNA was detected by Q-RT-PCR. The primers and probe (sense primer, 5′-AGCCTTCAGTTTCTTGCTGATGT-3′; probe, 5′-6-FAM-AAATCCTCCTAACAAGCGGGTTCCAGG-TAMRA-3′; antisense primer, 5′-TGTTGCGAAAGGACCAACAG-3′) were designed to be specific for the BVDV NS5B region by using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems). A standard curve with a linear range of at least 6 log units was obtained (data not shown). Ribavirin (Schering-Plough, Raritan, N.J.) was used as the positive control in these experiments.

Q-PCR assay for mitochondrial DNA and rRNA gene.

Low-passage-number HepG2 cells, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.), were seeded at 5,000 cells/well in collagen-coated 96-well plates. Test compounds were added to the medium to obtain final concentrations of 10 μM. On culture day 7, cellular nucleic acids were prepared by using commercially available columns (RNeasy 96 kit; Qiagen). These kits copurify RNA and DNA, and hence, total nucleic acids were eluted from columns in 140 μl of water. The mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit II (COXII) gene and the β-actin or rRNA gene were amplified from 5 μl by a multiplex Q-PCR protocol that uses suitable primers and probes for both target and reference amplifications (designed with Primer Express software [Applied Biosystems]): for COXII, sense primer, 5′-TGCCCGCCATCATCCTA-3′; probe, 5′-tetrachloro-6-carboxyfluorescein-TCCTCATCGCCCTCCCATCCC-TAMRA-3′; and antisense probe, 5′-CGTCTGTTATGTAAAGGATGCGT-3′; for exon 3 of the β-actin gene (GenBank accession number E01094), sense primer, 5′-GCGCGGCTACAGCTTCA-3′; probe, 5′-6-FAM-CACCACGGCCGAGCGGGA-TAMRA-3′; and antisense probe, 5′-TCTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGAT-3′. The primers and probes for the rRNA gene were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Standard curves obtained with 1 log of diluted total HepG2 DNA were linear over more than 5 log units. In addition, the efficiencies of the target (COXII DNA) and reference (β-actin DNA or rRNA gene) amplifications were approximately equal, because the slope of the line for the change in the cycle threshold (CT; CT for β-actin minus CT for mitochondrial DNA [ΔCT]) was less than 0.1 (data not shown). Since equal amplification efficiencies were obtained for both genes, the comparative CT method was used to investigate potential inhibition of mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ. The comparative CT method uses arithmetic formulas in which the amount of target (COXII gene) is normalized to the amount of an endogenous reference (the β-actin or rRNA gene) and is relative to a calibrator (a control with no drug at day 7). The arithmetic formula for this approach is given by  , where ΔΔCT is (CT for average target test sample − CT for target control) − (CT for average reference test −CT for reference control) (User Bulletin 2; Applied Biosystems) (10).

, where ΔΔCT is (CT for average target test sample − CT for target control) − (CT for average reference test −CT for reference control) (User Bulletin 2; Applied Biosystems) (10).

Cytotoxicity assays.

HepG2 and human PBM cells (5 × 104 cells per well) were seeded in 96-well plates in the presence of increasing concentrations of the test compound and incubated in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. After a 3-day incubation for HepG2 cells or a 5-day incubation for human PBM cells, cell viability was measured using the CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution cell proliferation assay (Promega, Madison, Wis.).

RESULTS

Anti-HIV-1 activity (Q-RT-PCR versus RT assay).

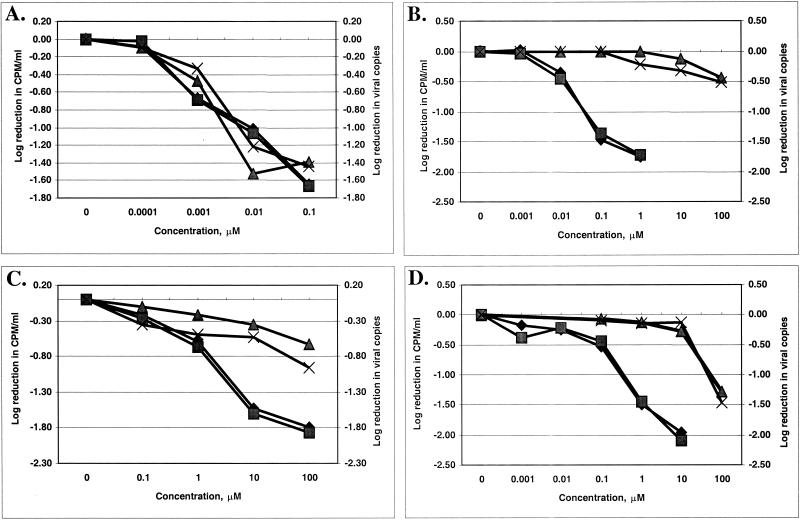

The activities of the eight candidate antiviral compounds against three HIV-1 strains (LAI, xxBRU, and lamivudine-resistant strain xxBRU-184V) were compared to those of AZT, lamivudine, and d-D4FC in a 5-day assay with phytohemagglutinin-stimulated human PBM cells. The culture supernatants were tested for HIV-1 at day 5 by two different methodologies: (i) the Q-RT-PCR, with the results presented as the log number of copies per milliliter, and (ii) the endogenous viral RT assay with cell supernatants, with the results presented as the log number of counts per minute per milliliter. Some representative results are shown in Fig. 2. Although the two methodologies measured different parameters (viral RNA versus active RT enzyme), the results were not markedly different from each other (Fig. 2). A summary of the data, expressed as the effective concentration required to reduce the viral RNA level or the RT activity by 90% (EC90) for the three HIV-1 strains, is given in Table 1. All compounds were tested by routine MTT or MTS toxicity assays and had 50% inhibitory concentrations equal to or greater than 87 μM for the cells evaluated (HepG2 and human PBM cells).

FIG. 2.

Dose-response curves for anti-HIV-1 activities of test compounds. (A) AZT; (B) lamivudine; (C) compound 3b; (D) compound 1b. ⧫, RT assay with strain xxBRU; ▪, Q-RT-PCR with strain xxBRU; ▴, RT assay with strain xxBRU-184V; ×, Q-RT-PCR with strain xxBRU-184V.

TABLE 1.

Anti-HIV-1 activities of nucleosides in acutely infected human PBM cells

| Compound | RT assaya

|

HIV-1 Q-RT-PCR assaya

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC90 (μM)

|

FIb | EC90 (μM)

|

FI | |||||

| LAI | xxBRU | xxBRU-184V | LAI | xxBRU | xxBRU-184V | |||

| 1a | 25.3 | 35.5 | 572 | 16.1 | 50.6 | 35.4 | >100 | >2.8 |

| 2a | 34.5 | 37.5 | 494 | 13.2 | 36.3 | 34.8 | >100 | >2.8 |

| 1b | 0.67 | 0.14 | 82.0 | 586 | 0.92 | 0.60 | 68.4 | 115 |

| 2b | 0.12 | 0.14 | 67.0 | 479 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 53.0 | 333 |

| 3a | 11.9 | 5.0 | 125 | 25.0 | 24.6 | 5.2 | 65.8 | 12.8 |

| 4a | >100 | 119 | >100 | <1 | >100 | 73.9 | >100 | >1.4 |

| 3b | 3.3 | 1.4 | 1,569 | 1,121 | 4.1 | 2.1 | >100 | >50 |

| 4b | 2.6 | 1.1 | >100 | >100 | 4.3 | 0.94 | >100 | >100 |

| AZT | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.00 |

| Lamivudine | 0.13 | 0.08 | 535 | 6,688 | 0.37 | 0.06 | >100 | >1,562 |

| D-D4FC | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 1.9 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.97 |

The supernatant was used in all assays to quantify viral production.

FI, fold increase (EC90 for HIV-1xxBRU-184V/EC90 for HIV-1xxBRU).

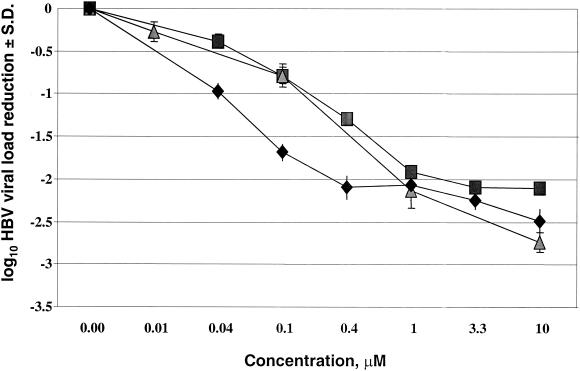

Results of assays for anti-HBV (Q-PCR) and anti-BVDV (Q-RT-PCR) activities.

The time course of HBV induction in HepAD38 cells was investigated. Following suppression of HBV for 2 days (with medium containing tetracycline) and a 5-day period without viral suppression (with tetracycline-free medium), the following observations were made: (i) shortly after the seeding of HBV, viral DNA was detected in the cell supernatant, but the quantities in the seeding medium did not change over the three sampling times (days 0, 1, and 2). In addition, it was noted that (ii) tetracycline completely shut down HBV DNA expression, and (iii) at 5 days after the removal of tetracycline, there was an increase in the HBV DNA level in the cell supernatant of approximately 2.5 log units.

The EC90s of the eight candidate compounds for HBV were determined in HepAD38 cells. Potent inhibition of HBV production by lamivudine (EC90, 0.05 μM), compound 1b (EC90, 0.25 μM), and compound 2b (EC90, 0.25 μM) was seen (Fig. 3), while all other compounds were considered inactive (EC90s, >50 μM).

FIG. 3.

Dose-dependent suppression of HBV production in AD38 cells. ⧫, lamivudine; ▪, compound 1b; ▴, compound 2b.

The compounds shown in Fig. 1 were also tested for their potential to block the production of BVDV in MDBK cell supernatants. Ribavirin showed potent inhibition (EC90, 5 μM), but none of the test compounds prevented release of virus from the infected cells (EC90s, >200 μM).

Testing for mitochondrial DNA by Q-PCR.

In order to study the consequences of the possible inhibitory effects of these compounds on host DNA polymerases, nuclear and mitochondrial DNA levels were quantified and compared to those for the controls that received no treatment. Cells were incubated for 7 days with each compound at a concentration of 10 μM, followed by total nucleic acid extractions and multiplex Q-PCR of the rRNA gene and the mitochondrial COXII gene. Nucleic acids from cells exposed to the control compounds were also amplified by the multiplex Q-PCR for detection of mitochondrial DNA and the β-actin gene. The results, which were obtained by the comparative CT method, are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Relative quantitation of cellular gene products by the comparative CT method with HepG2 cells treated with various antiviral agents

| Compound | Avg ± SD ΔCTa

|

Avg ± SD ΔΔCTb

|

COXIIN for rRNA gene relative to levels for controlc | COXIIN for β-actin DNA relative to levels for controlc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COXII DNA | rRNA gene | β-Actin DNA | COXII DNA- rRNA gene | COXII DNA-β- actin gene | rRNA gene-β- actin gene | |||

| Control | 0 ± 0.42 | 0 ± 0.98 | 0 ± 0.65 | 0 ± 0.87 | 0 ± 0.57 | 0 ± 0.87 | 1 (0.59-1.69) | 1 (0.68-1.48) |

| Zalcitabine | 2.27 ± 0.26d | 0.18 ± 0.53 | −0.62 ± 0.21d | 2.09 ± 0.65d | 2.9 ± 0.23d | 0.81 ± 0.59 | 0.23 (0.15-0.37) | 0.13 (0.11-0.16) |

| AZT | 0.25 ± 0.13 | 0.86 ± 0.55 | 0.10 ± 0.38 | −0.61 ± 0.56 | 0.16 ± 0.44 | 0.76 ± 0.87 | 1.52 (1.03-2.24) | 0.90 (0.66-1.22) |

| Lamivudine | 0.08 ± 0.33 | 0.47 ± 0.51 | 0.11 ± 0.23 | −0.39 ± 0.50 | −0.02 ± 0.43 | 0.36 ± 0.66 | 1.31 (0.92-1.88) | 1.02 (0.75-1.37) |

| (+)-BCH-189 | 2.16 ± 0.32d | −0.14 ± 0.61 | −0.36 ± 0.31 | 2.3 ± 0.66d | 2.53 ± 0.36d | 0.23 ± 0.39 | 0.20 (0.13-0.32) | 0.17 (0.14-0.22) |

| FIAL | 0.09 ± 0.17 | NDe | 0.23 ± 0.01 | ND | −0.14 ± 0.12 | ND | ND | 1.10 (1.01-1.20) |

| d4T | 0.29 ± 0.01 | ND | 0.05 ± 0.06 | ND | 0.23 ± 0.04 | ND | ND | 0.85 (0.79-0.88) |

| Acyclovir | −0.37 ± 0.08 | ND | 0.17 ± 0.01 | ND | −0.54 ± 0.06 | ND | ND | 1.45 (1.34-1.52) |

| 1a | −0.29 ± 0.19 | −0.08 ± 0.50 | ND | −0.21 ± 0.51 | ND | ND | 1.16 (0.81-1.64) | ND |

| 2a | −0.49 ± 0.31 | −0.44 ± 0.31 | ND | −0.05 ± 0.37 | ND | ND | 1.04 (1.34-0.80) | ND |

| 1b | −0.16 ± 0.17 | −0.51 ± 0.35 | ND | 0.36 ± 0.41 | ND | ND | 0.78 (0.59-1.04) | ND |

| 2b | −0.3 ± 0.46 | 0.19 ± 0.56 | ND | −0.49 ± 0.60 | ND | ND | 1.40 (0.93-2.13) | ND |

| 3a | −0.14 ± 0.10 | 0.81 ± 0.60 | ND | −0.96 ± 0.56 | ND | ND | 1.94 (1.31-2.87) | ND |

| 4a | −0.39 ± 0.43 | −0.45 ± 0.60 | ND | 0.06 ± 0.29 | ND | ND | 0.96 (0.78-1.17) | ND |

| 3b | −0.05 ± 0.16 | 0.49 ± 0.77 | ND | −0.55 ± 0.75 | ND | ND | 1.46 (0.87-2.47) | ND |

| 4b | −0.06 ± 0.24 | 0.10 ± 0.44 | ND | −0.16 ± 0.56 | ND | ND | 1.12 (0.76-1.64) | ND |

Value obtained by subtracting the average control CT value (n = 18 datum points) from the average CT value (n = 6 datum points).

Value obtained by subtraction of average ΔCT from the values for the indicated parameters.

COXIIN normalized COXII DNA levels relative to the levels for the control, as given by the expression 2−ΔΔCT; the values in parentheses are the ranges of between ΔΔCT plus the standard deviation and ΔΔCT minus the standard deviation.

Significantly different from the value for the control; P values were obtained from a two-tailed distribution two-sample unequal variance t test; significance was set at 0.005 (boldface).

ND, not determined.

Treatment with d-ddC and (+)-BCH-189 caused significant reductions in COXII DNA levels (ΔCT values, 2.27 and 2.16, respectively), while treatment with none of the test compounds resulted in significant decreases in COXII DNA levels. In tests for the rRNA gene, there were no significant differences in the ΔCT values obtained with the test compounds compared to those obtained with the controls. In tests for the β-actin gene, a minor but significant increase (ΔCT, −0.62) in the amount of DNA in d-ddC-treated cultures was noted, but this increase was most likely attributed to a PCR-primer effect.

After normalization of the values and relative to the values for the controls that received no treatment, d-ddC and (+)-BCH-189 significantly reduced the total amount of COXII DNA by more than 2 ΔΔCT, while none of the eight new test compounds caused any significant reduction in the amount of COXII DNA.

DISCUSSION

During the course of this study, the Q-RT-PCR technology was used for the first time to design a platform of assays that allows evaluation of candidate antiviral compounds and that simultaneously scores the effect on host nucleic acid levels. These assays included (i) an assay for the HIV-1 genotype B load, (ii) an assay for the HBV load, (iii) an assay for the BVDV load, (iv) an assay for human β-actin gene, (v) an assay for the mitochondrial COXII gene, and (vi) an assay for the rRNA gene. The advantage of the technology is that several of these assays can be used simultaneously through the multiplex PCR method, combined with the powerful comparative CT method. Such an approach increased the throughput and eliminated the adverse effects of variations introduced as a consequence of the use of dilutions for external standard curves. However, in order to amplify a target and an endogenous control in the same tube, limiting primer concentrations that do not affect CT values should be identified. The significant increase in the CT value observed for β-actin DNA in tests with d-ddC is most likely a consequence of the multiplex reaction, in which the β-actin gene is more efficiently amplified as a consequence of a reduced amount of the COXII DNA template. Since it remains unexplained why this increase in CT was not observed with (+)-BCH-189, more fine-tuning of the β-actin gene-COXII DNA multiplex condition is needed, but the effect of d-ddC on cellular DNA levels also needs to be further studied.

The Q-PCR and Q-RT-PCR methodologies are excellent tools for reliable evaluation of antiviral agents in cell-based protocols. Two new classes of antiviral compounds were evaluated side by side with a selection of antiviral compounds that are approved for use by the FDA or that are in clinical trials. For the experiments with HIV-1 (Table 1 and Fig. 2), the level of virus production in this system was very high, with a total of up to 3 × 108 copies/ml in the untreated samples (data not shown) (23). Upon addition of antiviral compounds to the culture medium, a dose-related decrease in the level of virus production was observed.

The following general conclusions for this series of nucleoside analogues can be made: (i) the β-l-enantiomers were more potent than the corresponding β-d-enantiomers; (ii) compounds were less potent against lamivudine-resistant HIV-1 strains, indicating cross-resistance with lamivudine-selected xxBRU-184V viral strains; (iii) the antiviral activity of d-D4FC was strongly reduced by introducing a 3′-fluorine in the sugar moiety; (iv) the 5-fluorocytosine base modification did not improve the antiviral activity and did not change the toxicity pattern significantly (50% inhibitory concentrations, >87 μM for all compounds tested); (v) modifications in the sugar ring of cytosine nucleoside analogs with a 4′-thia instead of an oxygen (especially compounds 3b and 4b) resulted in compounds with reduced potencies against lamivudine-resistant virus; and (vi) the one-step Q-RT-PCR assay gave results comparable to those obtained by the endogenous RT assay, eliminating the need for experiments that use radioactive compounds and a shorter turnaround time.

Many studies on the anti-HBV activities of test compounds have used the HepG2.2.15 cell system with a semiquantitative HBV Southern blot technology (1, 12). When we used the HepG2.2.15 system and the Q-PCR technology, we found that there was a very narrow dynamic range, with a maximal reduction of 0.6 log for 10 μM lamivudine. Therefore, the HepAD38 system (11, 13) was evaluated, and a dynamic range of virus production of approximately 2.5 log units of HBV DNA in the cell supernatant was observed. Compared to the technology with HepG2.2.15 cells, the Q-PCR approach with HepAD38 cells gave a broader dynamic range and shorter incubation time. The eight candidate compounds and lamivudine were tested with HepAD38 cells, and as expected, lamivudine was potent and caused a large reduction in the amount of HBV DNA in the cell supernatant (EC90, 0.05 μM). The only test nucleoside analogs that were able to reduce the HBV DNA levels in the cell supernatant were compounds 1b and 2b (which were as potent as lamivudine, with EC90s of 0.25 μM). However, in the HIV-1 RT assay, these compounds were found 586- and 479-fold less potent, respectively, against a lamivudine-resistant HIV-1 strain (Table 1). Since both compounds are l-nucleosides (25), these data indicate that the β-l-2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-fluoro sugar configuration has activity and a resistance profile against HIV-1 similar to those of compounds with the β-l-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thia configuration (e.g., lamivudine).

To date, seven nucleoside analogs have received approval from FDA for the treatment of HIV infection, and two (lamivudine and, recently, adefovir) have received approval for the treatment of HBV infection. The general symptoms of nucleoside analog toxicity in patients resemble those of inherited mitochondrial diseases (i.e., hepatitic steatosis, lactic acidosis, myopathy, nephrotoxicity, peripheral neuropathy, multiple symmetric lipomatosis, and pancreatitis) (2, 16). HIV-infected individuals undergoing prolonged antiviral treatment have shown symptoms that include peripheral neuropathy (seen with the d-enantiomers d4T, dideoxyinosine [ddI], and ddC), myopathy and bone marrow suppression (seen with AZT), and pancreatitis (seen with ddI) (3). Since all these compounds in the 5′-triphosphate form lack a 3′-OH and stop virus replication by chain termination, there is a concern that these nucleoside analogues are also substrates for the human DNA polymerase γ, resulting in inhibition of mitochondrial DNA replication and, subsequently, toxic side effects (9, 17). The hierarchy of the activities of the established approved nucleoside analogs for mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ inhibition is as follows: d-ddC > ddI > d4T > lamivudine > AZT > carbovir (9). Differences in toxicity may result from a combination of cellular uptake, transport to the mitochondria, phosphorylation, rates of incorporation into and removal from replicating mitochondrial DNA, and impairment of mitochondrial enzymes (4). However, there is often a disconnect between the inhibition of DNA polymerase γ in cell-free systems and the levels of synthesis in cell-associated systems (4). In an attempt to directly provide data on intracellular mitochondrial DNA levels, a Q-PCR technology was designed and the relative amounts of COXII DNA were calculated by using the comparative CT method. d-ddC and (+)-BCH-189 served as positive controls and were confirmed to reduce mitochondrial COXII DNA levels (6). Also, in agreement with previous observations, no changes in normalized mitochondrial DNA levels were observed after FIAU and D4T treatment (5, 7, 20). None of the eight test nucleoside analogs caused any significant reductions in COXII DNA levels. However, the Q-PCR technology described herein does not predict the potential incorporation of the inhibitor into mitochondrial DNA or other mitochondrial aberrations such as mitochondrial morphology changes (e.g., loss of cristae), lactic acid production, and lipid droplet formation. Prior to clinical development, it is recommended that the effects of these compounds on those parameters be investigated.

In conclusion, a platform of quantitative assays with uniform antiviral agents and cell lines was designed and used to evaluate two groups of potential antiviral nucleosides. Some of these compounds showed potent and selective anti-HIV activities but reduced sensitivities when they were used against a lamivudine-resistant HIV-1 strain.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by NIH grants 1R37AI-41890 and 1RO1AI-32351 and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

R. F. Schinazi is founder of Pharmasset Ltd., and his particulars have been reviewed by Emory University's Conflict of Interest Committee. R. F. Schinazi's group received no funding from Pharmasset to perform this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balakrishna Pai, S., S. H. Liu, Y. L. Zhu, C. K. Chu, and Y. C. Cheng. 1996. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus by a novel l-nucleoside, 2′-fluoro-5- methyl-β-l-arabinofuranosyl uracil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:380-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinkman, K., J. A. Smeitink, J. A. Romijn, and P. Reiss. 1999. Mitochondrial toxicity induced by nucleoside-analogue reverse-transcriptase inhibitors is a key factor in the pathogenesis of antiretroviral-therapy-related lipodystrophy. Lancet 354:1112-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinkman, K., H. J. ter Hofstede, D. M. Burger, J. A. Smeitink, and P. P. Koopmans. 1998. Adverse effects of reverse transcriptase inhibitors: mitochondrial toxicity as common pathway. AIDS 12:1735-1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang, C. N., V. Skalski, J. H. Zhou, and Y.-C. Cheng. 1992. Biochemical pharmacology of (+)- and (−)-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine as anti-hepatitis B virus agents. J. Biol. Chem. 267:22414-22420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colacino, J. M. 1996. Mechanisms for the anti-hepatitis B virus activity and mitochondrial toxicity of fialuridine (FIAU). Antivir. Res. 29:125-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui, L., R. F. Schinazi, G. Gosselin, J. L. Imbach, C. K. Chu, R. F. Rando, G. R. Revankar, and J.-P. Sommadossi. 1996. Effect of beta-enantiomeric and racemic nucleoside analogues on mitochondrial functions in HepG2 cells. Implications for predicting drug hepatotoxicity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 52:1577-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cui, L., S. Yoon, R. F. Schinazi, and J.-P. Sommadossi. 1995. Cellular and molecular events leading to mitochondrial toxicity of 1-(2-deoxy-2-fluoro-1-beta-d-arabinofuranosyl)-5-iodouracil in human liver cells. J. Clin. Investig. 95:555-563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng, J. Y., A. A. Johnson, K. A. Johnson, and K. S. Anderson. 2001. Insights into the molecular mechanism of mitochondrial toxicity by AIDS drugs. J. Biol. Chem. 276:23832-23837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson, A. A., A. S. Ray, J. W. Hanes, Z. Suo, J. M. Colacino, K. S. Anderson, and K. A. Johnson. 2001. Toxicity of nucleoside analogs and the human mitochondrial DNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:40847-40857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson, M. R., K. Wang, J. B. Smith, M. J. Heslin, and R. B. Diasio. 2000. Quantitation of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase expression by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Anal. Biochem. 278:175-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King, R. W., and S. K. Ladner. 2000. Hep AD38 assay: a high-throughput, cell-based screen for the evaluation of compounds against hepatitis B virus. Humana Press Inc., Totowa, N.J. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Korba, B. E., and J. L. Gerin. 1992. Use of a standardized cell culture assay to assess activities of nucleoside analogs against hepatitis B virus replication. Antivir. Res. 19:55-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ladner, S. K., M. J. Otto, C. S. Barker, K. Zaifert, G. H. Wang, J. T. Guo, C. Seeger, and R. W. King. 1997. Inducible expression of human hepatitis B virus (HBV) in stably transfected hepatoblastoma cells: a novel system for screening potential inhibitors of HBV replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1715-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai, V. C., W. Zhong, A. Skelton, P. Ingravallo, V. Vassilev, R. O. Donis, Z. Hong, and J. Y. Lau. 2000. Generation and characterization of a hepatitis C virus NS3 protease-dependent bovine viral diarrhea virus. J. Virol. 74:6339-6347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larder, B. 2001. Mechanisms of HIV-1 drug resistance. AIDS 15:S27-S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis, W., and M. C. Dalakas. 1995. Mitochondrial toxicity of antiviral drugs. Nat. Med. 1:417-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin, J. L., C. E. Brown, N. Matthews-Davis, and J. E. Reardon. 1994. Effects of antiviral nucleoside analogs on human DNA polymerases and mitochondrial DNA synthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:2743-2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKenzie, R., M. W. Fried, R. Sallie, H. Conjeevaram, A. M. Di Bisceglie, Y. Park, B. Savarese, D. Kleiner, M. Tsokos, and C. Luciano. 1995. Hepatic failure and lactic acidosis due to fialuridine (FIAU), an investigational nucleoside analogue for chronic hepatitis B. N. Engl. J. Med. 333:1099-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nam, J. H., J. Bukh, R. H. Purcell, and S. U. Emerson. 2001. High-level expression of hepatitis C virus (HCV) structural proteins by a chimeric HCV/BVDV genome propagated as a BVDV pseudotype. J. Virol. Methods 97:113-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan-Zhou, X. R., L. Cui, X. J. Zhou, J.-P. Sommadossi, and V. M. Darley-Usmar. 2000. Differential effects of antiretroviral nucleoside analogs on mitochondrial function in HepG2 cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:496-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pas, S. D., E. Fries, R. A. De Man, A. D. Osterhaus, and H. G. Niesters. 2000. Development of a quantitative real-time detection assay for hepatitis B virus DNA and comparison with two commercial assays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2897-2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schinazi, R. F., B. A. Larder, and J. W. Mellors. 2000. Mutations in retroviral genes associated with drug resistance: 2000-2001 update. Int. Antivir. News 8:65-91. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schinazi, R. F., R. M. J. Lloyd, M. H. Nguyen, D. L. Cannon, A. McMillan, N. Ilksoy, C. K. Chu, D. C. Liotta, H. Z. Bazmi, and J. W. Mellors. 1993. Characterization of human immunodeficiency viruses resistant to oxathiolane-cytosine nucleosides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:875-881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schinazi, R. F., J. W. Mellors, H. Z. Bazmi, S. Diamond, S. Garber, K. Gallagher, R. Geleziunas, R. Klabe, M. Pierce, M. Rayner, J.-T. Wu, H. Zhang, J. Hammond, L. Bacheler, D. J. Manion, M. J. Otto, L. J. Stuyver, G. Trainor, D. C. Liotta, and S. Erickson-Viitanen. 2002. DPC 817: a cytidine nucleoside analog with activity against zidovudine- and lamivudine-resistant viral variants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1394-1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schinazi, R. F., S. Schlueter-Wirtz, and L. J. Stuyver. 2001. Early detection of mixed mutations selected by antiretroviral agents in HIV-infected primary human lymphocytes. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 12:61-65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]