Abstract

A chromosome-encoded β-lactamase gene, cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli from Kluyvera georgiana reference strain CUETM 4246-74 (DSM 9408), encoded the extended-spectrum β-lactamase KLUG-1, which shared 99% amino acid identity with the plasmid-mediated β-lactamase CTX-M-8. This work provides further evidence that Kluyvera spp. may be the progenitor(s) of CTX-M-type β-lactamases.

Plasmid-mediated CTX-M-type extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) are being increasingly reported worldwide in enterobacterial isolates (20). They may be grouped according to their amino acid identity in four clusters: CTX-M-1 (CTX-M-1, -3, -10, -11, -12, -15, and -22), CTX-M-2 (CTX-M-2, -4, -5, -6, -7, and -20 and Toho-1), CTX-M-8, and CTX-M-9 (CTX-M-9, -13, -14/-18, -16, -19, and -21 and Toho-2) (2-4, 6, 10, 11, 13, 15-18, 20) (GenBank accession no. AY080894). These β-lactamases do not hydrolyze ceftazidime at a high level except for CTX-M-15, CTX-M-16, and CTX-M-19 (2, 10, 15). The natural producers of CTX-M enzymes have been identified in rare cases. The chromosome-encoded β-lactamases KLUC-1 from Kluyvera cryocrescens (5) and KLUA-1 from K. ascorbata (8) share 86 and 99% amino acid identity with the plasmid-borne CTX-M-1 and CTX-M-2 subgroups, respectively.

To elucidate further natural producers of CTX-M-type β-lactamase genes, we studied the β-lactamase content of K. georgiana, which belongs to the genus Kluyvera, which includes such species as K. cochleae, K. ascorbata, and K. cryocrescens (12). Kluyvera spp. have been rarely reported from clinical specimens (19). Detailed susceptibility of K. georgiana to β-lactams is not known and a preliminary disk diffusion antibiogram indicated that reference strain K. georgiana CUETM 4246-74 displayed a weakly expressed clavulanic acid-inhibited penicillinase phenotype (data not shown).

Cloning and sequencing identified a chromosomally encoded Ambler class A enzyme that shared 99% identity with CTX-M-8, the single representative of one of the four CTX-M clusters.

Bacterial strains and plasmid analysis.

K. georgiana reference strain CUETM 4246-74 (DSM 9408) has been identified previously (12). The Escherichia coli DH10B reference strain was used for cloning experiments. Plasmid DNA extractions, performed according to several methods as described previously (10, 14), failed to identify a plasmid.

Cloning and sequence analysis of the β-lactamase gene from K. georgiana.

Whole-cell DNA of K. georgiana CUETM 4246-74 was extracted as described previously (14), digested with Sau3AI restriction enzyme, and ligated into the BamHI site of pBK-CMV phagemid (14). Ten E. coli DH10B recombinant clones were obtained after selection onto Mueller-Hinton plates containing 30 μg of kanamycin and 50 μg of amoxicillin per ml. The recombinant plasmid (pKG-2) that had the shortest insert (1,781 bp) was sequenced as described previously (14).

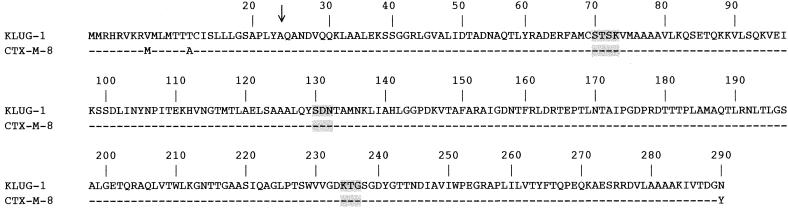

An open reading frame of 876 bp was identified. Within the deduced protein of this open reading frame (291 amino acids), named KLUG-1 (for “Kluyvera georgiana”), characteristic elements of Ambler class A β-lactamases were identified (Fig. 1) (9). Computer analysis indicated a putative cleavage site for the mature protein located at the same position compared to that of β-lactamase KLUC-1 of K. cryocrescens (Fig. 1) (9). Isoelectric focusing analysis, performed as previously reported (14), showed that homogenates of K. georgiana 4246-74 and of E. coli DH10B (pKG-2) gave a single and identical β-lactamase with a pI value of 7.6.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the KLUG-1 amino acid sequence with that of CTX-M-8 from C. amalonaticus (3). The numbering is according to the scheme of Ambler et al. (1). Dashes represent identical amino acid residues. The vertical arrow is the putative cleavage site of the leader peptide of the mature β-lactamase KLUG-1. Three structural elements characteristic of class A β-lactamases are boxed in gray (9).

The β-lactamase KLUG-1 shared 99% amino acid identity with the plasmid-mediated CTX-M-8 enzyme identified in Brazilian isolates of Citrobacter amalonaticus, Enterobacter cloacae, and Enterobacter aerogenes (3) (Fig. 1). Only one amino acid change (290) was noted between CTX-M-8 and KLUG-1 sequences that was located in the C termini. In addition, two amino acid changes were identified in the leader peptide sequence (Fig. 1). KLUG-1 shared 83 and 77% amino acid identity with the chromosomally encoded β-lactamases KLUA-1 from K. ascorbata (8) and KLUC-1 from K. cryocrescens (5).

Just upstream of blaKLUG-1, a 533-bp DNA fragment was identified from recombinant plasmid pKG-2. Within this fragment, the 389-bp 5′-end located sequence shared 87% identity with DNA sequence upstream of blaKLUA-1 (8), whereas the 336-bp 5′-end located sequence shared 88% identity with DNA sequence upstream of blaKLUC-1 (data not shown) (5). This result indicated similarities in the DNA sequences surrounding the β-lactamases genes in some Kluyvera species that may constitute similar loci.

A Southern transfer of an agarose gel containing whole-cell DNA of K. georgiana CUETM 4246-74 was performed (18) and hybridized with a PCR-generated 800-bp internal fragment of blaKLUG-1 (primer KLUG-1a, 5′-GATGAGACATGCGTTAAGC-3′; primer KLUG-1b, 5′-CTAATTACCGTCAGTGACG-3′) as a labeled probe (15). A positive signal was detected at the chromosomal migration position indicating the chromosomal origin of blaKLUG-1 (data not shown).

Susceptibility testing.

MICs of selected β-lactams were determined as described previously (14). K. georgiana CUETM 4246-74 was of intermediate susceptibility to amoxicillin, ticarcillin, and cephalothin (Table 1). It was susceptible to the other β-lactam antibiotics tested. Once cloned in pBK-CMV (pKG-2) and expressed in E. coli DH10B (Table 1), KLUG-1 conferred, in addition, resistance or reduced susceptibility to piperacillin, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, cefepime, cefpirome, and aztreonam. The resistance profile observed for E. coli DH10B (pKG-2) corresponded to that conferred by the plasmid-mediated CTX-M-8 enzyme that does not compromise ceftazidime significantly (3). The addition of clavulanic acid and tazobactam lowered the β-lactam MICs for strains expressing KLUG-1. These results indicated that KLUG-1 is a clavulanic acid-inhibited ESBL that is weakly expressed in K. georgiana.

TABLE 1.

MICs of β-lactams for K. georgiana reference strain 4246-74, E. coli DH10B (pKG-2), and E. coli DH10B reference strain

| β-Lactam(s)a | MIC (μg/ml)b

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| K. georgiana CUETM 4246-74 | E. coli DH10B (pKG-2) | E. coli DH10B | |

| Amoxicillin | 4 | 512 | 2 |

| Amoxicillin + CLA | 1 | 8 | 2 |

| Ticarcillin | 16 | >512 | 1 |

| Ticarcillin + CLA | 1 | 256 | 1 |

| Piperacillin | 2 | 512 | 1 |

| Piperacillin + TZB | 0.25 | 2 | 1 |

| Cephalothin | 4 | >512 | 2 |

| Cefuroxime | 4 | >512 | 2 |

| Cefotaxime | 0.25 | 32 | <0.06 |

| Cefotaxime + CLA | 0.06 | 0.25 | <0.06 |

| Cefotaxime + TZB | 0.06 | 0.12 | <0.06 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.12 | 1 | <0.06 |

| Ceftazidime + CLA | <0.06 | <0.06 | <0.06 |

| Ceftazidime + TZB | <0.06 | <0.06 | <0.06 |

| Cefepime | 0.12 | 16 | <0.06 |

| Cefepime + CLA | <0.06 | 0.12 | <0.06 |

| Cefpirome | 0.12 | 16 | <0.06 |

| Cefpirome + CLA | <0.06 | 0.12 | <0.06 |

| Cefpirome + TZB | <0.06 | 0.06 | <0.06 |

| Cefoxitin | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| Moxalactam | <0.06 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| Aztreonam | 0.06 | 16 | 0.06 |

| Imipenem | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

CLA, clavulanic acid at a fixed concentration of 2 μg/ml; TZB, tazobactam at a fixed concentration of 4 μg/ml.

K. georgiana CUETM 4246-74 and E. coli DH10B (pKG-2) produced β-lactamase KLUG-1.

Conclusion.

This report underlines further that enterobacterial species may be natural producers of Ambler class A ESBLs that are undetectable in these species on the sole basis of analysis of a disk diffusion antibiogram. Thus, it seems possible to select high-level producers via mutations occurring in the promoter sequences as described for the β-lactamase of K. oxytoca (7). Although phylogenetically related, the Kluyvera species produce different β-lactamases sharing similar substrate profiles. Finally, we identified the potential producer of a subgroup of CTX-M enzymes, CTX-M-8, that shares 83 to 88% identities with the other CTX-M β-lactamases (3).

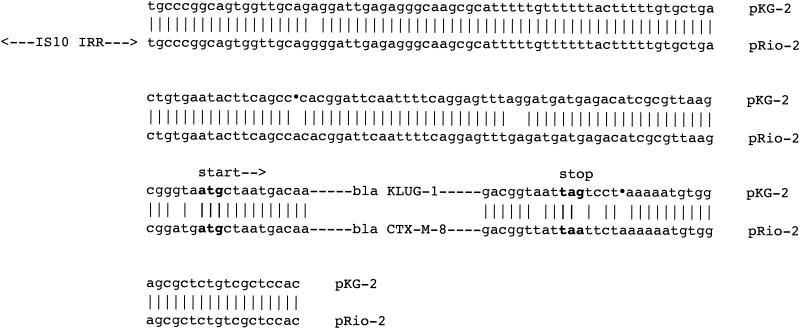

In many cases, plasmid-encoded blaCTX-M genes are located downstream of ISEcp1-like insertion sequences (4, 6, 10), whereas an IS10-like element was identified upstream of blaCTX-M-8 gene (GenBank accession no. AF189721). The immediate upstream- and downstream-located sequences of blaCTX-M-8 and blaKLUG-1 share consistent identity (Fig. 2). Thus, this IS10-like element may be involved in mobilization of the downstream-located β-lactamase gene.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the surrounding DNA sequences of blaKLUG-1 and blaCTX-M-8 of recombinant plasmid pKG-2 and natural plasmid pRio-2, respectively. Boldfaced nucleotides indicate start and stop codons of β-lactamase genes. Vertical bars indicate identical nucleotides, whereas dots represent deleted nucleotides. IS10 IRR refers to the inverted repeat right of an IS10-like element.

The reason why Kluyvera species may be a source of plasmid-mediated CTX-M enzymes has to be investigated, whereas Kluyvera strains are rarely isolated in clinical microbiology.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported here has been assigned to the GenBank nucleotide database under accession no. AF501233.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the Ministères de l'Education Nationale et de la Recherche (UPRES-EA), Université Paris XI, Faculté de Médecine Paris-Sud, Paris, France.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambler, R. P., A. F. W. Coulson, J.-M. Frère, J. M. Ghuysen, B. Joris, M. Forsman, R. C. Lévesque, J. Tiraby, and S. G. Waley. 1991. A standard numbering scheme for the class A β-lactamases. Biochem. J. 276:269-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonnet, R., C. Dutour, J. L. M. Sampaio, C. Chanal, D. Sirot, R. Labia, C. De Champs, and J. Sirot. 2000. Novel cefotaximase (CTX-M-16) with increased catalytic efficiency due to substitution Asp-240 to Gly. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2269-2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonnet, R., J. L. M. Sampaio, R. Labia, C. De Champs, D. Sirot, C. Chanal, and J. Sirot. 2000. A novel CTX-M β-lactamase (CTX-M-8) in cefotaxime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated in Brazil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1936-1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chanawong, A., F. H. M'Zali, J. Heritage, J.-X. Xiong, and P. M. Hawkey. 2002. Three cefotaximases, CTX-M-9, CTX-M-13, and CTX-M-14, among Enterobacteriaceae in the People's Republic of China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:630-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decousser, J.-W., L. Poirel, and P. Nordmann. 2001. Characterization of a chromosomally encoded extended-spectrum class A β-lactamase from Kluyvera cryocrescens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3595-3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dutour, C., R. Bonnet, H. Marchandin, M. Boyer, C. Chanal, D. Sirot, and J. Sirot. 2002. CTX-M-1, CTX-M-3, and CTX-M-14 β-lactamases from Enterobacteriaceae in France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:534-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fournier, B., P. H. Lagrange, and A. Philippon. 1996. Beta-lactamase gene promoters of 71 clinical strains of Klebsiella oxytoca. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:460-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humeniuk, C., G. Arlet, V. Gauthier, P. Grimont, R. Labia, and A. Philippon. 2002. β-Lactamases of Kluyvera ascorbata, probable progenitors of some plasmid-encoded CTX-M types. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3045-3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joris, B., P. Ledent, O. Dideberg, E. Fonzé, J. Lamotte-Brasseur, J. A. Kelly, J. M. Ghusyen, and J.-M. Frère. 1991. Comparison of the sequences of class A β-lactamases and of the secondary structure elements of penicillin-recognizing proteins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:2294-2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karim, A., L. Poirel, S. Nagarajan, and P. Nordmann. 2001. Plasmid-mediated extended-spectrum β-lactamase (CTX-M-3 like) from India and gene association with insertion sequence ISEcp1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 201:237-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kariuki, S., J. E. Corkill, G. Revathi, R. Musoke, and C. A. Hart. 2001. Molecular characterization of a novel plasmid-encoded cefotaximase (CTX-M-12) found in clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Kenya. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2141-2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Müller, H. E., D. J. Brenner, G. R. Fanning, P. A. Grimont, and P. Kämpfer. 1996. Emended description of Buttiauxella agrestis with recognition of six new species of Buttiauxella and two species of Kluyvera: B. ferragutiae sp. nov., B. gaviniae sp. nov., B. brennerae sp. nov., B. izardii sp. nov., B. noackiae sp. nov., B. warmboldiae sp. nov., K. cochleae sp. nov., and K. georgiana sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Microbiol. 46:50-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliver, A., J. C. Perez-Diaz, T. M. Coque, F. Baquero, and R. Canton. 2001. Nucleotide sequence and characterization of a novel cefotaxime-hydrolyzing β-lactamase (CTX-M-10) isolated in Spain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:616-620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poirel, L., I. Le Thomas, T. Naas, A. Karim, and P. Nordmann. 2000. Biochemical sequence analyses of GES-1, a novel class A extended-spectrum β-lactamase, and the class 1 integron In52 from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:622-632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poirel, L., T. Naas, I. Le Thomas, A. Karim, E. Bingen, and P. Nordmann. 2001. CTX-M-type extended-spectrum β-lactamase that hydrolyzed ceftazidime through a single amino acid substitution in the omega loop. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3355-3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabate, M., R. Tarrago, F. Navarro, E. Miro, C. Verges, J. Barbe, and G. Prats. 2000. Cloning and sequence of the gene encoding a novel cefotaxime-hydrolyzing β-lactamase (CTX-M-9) from Escherichia coli in Spain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1970-1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saladin, M., V. T. B. Cao, T. Lambert, J. L. Donay, J.-L. Hermann, Z. Ould-Hocine, C. Verdet, F. Delisle, A. Philippon, and G. Arlet. 2002. Diversity of CTX-M β-lactamases and their promoter regions from Enterobacteriaceae isolates in three Parisian hospitals. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 209:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 19.Sarria, J. C., A. M. Vidal, and R. C. Kimbrough III. 2001. Infections caused by Kluyvera species in humans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tzouvelekis, L. S., E. Tzelepi, P. T. Tassios, and N. J. Legakis. 2000. CTX-M-type β-lactamases: an emerging group of extended-spectrum enzymes. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 14:137-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]