Abstract

The 6-anilinouracils (AUs) constitute a new class of bactericidal antibiotics selective against gram-positive (Gr+) organisms. The AU family of compounds specifically inhibits a novel target, replicative DNA polymerase Pol IIIC. Like other antibiotics, AUs can be expected to engender the development of resistant bacteria. We have used a representative AU and clinically relevant strains of Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus to determine the frequency and mechanism(s) of resistance development. The frequency of resistance was determined by using N3-hydroxybutyl 6-(3′-ethyl-4′-methylanilino) uracil (HBEMAU) and commercially available antibiotics at eight times the MICs. For all five Gr+ organisms tested, the frequency of resistance to HBEMAU ranged from 1 × 10−8 to 3 × 10−10. The frequencies of resistance to the antibiotics tested, including rifampin, gentamicin, and ciprofloxacin, were either greater than or equal to those for HBEMAU. In order to understand the mechanism of resistance, HBEMAU-resistant organisms were isolated. MIC assays showed that the organisms had increased resistance to AU inhibitors but not to other families of antibiotics. Inhibition studies with DNA polymerases from HBEMAU-sensitive and -resistant strains demonstrated that the resistance was associated with Pol IIIC. DNA sequence analysis of the entire polC genes from both wild-type and resistant organisms revealed that the resistant organisms had a sequence change that mapped to a single amino acid codon in all strains examined.

The growing incidence of life-threatening infections caused by multiantibiotic-resistant gram-positive (Gr+) pathogens (such as Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus species) is a major problem in modern health care facilities (22). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) has become prominent as a cause of hospital-acquired (nosocomial) infections. Vancomycin remains the main antibacterial drug available for treatment of MRSA infections (19). Nevertheless, it is becoming apparent that high-level resistance to vancomycin is beginning to develop even among the staphylococci (1, 7). The presence of vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (1) and now even vancomycin-resistant S. aureus has been reported (7). In the last decade, a rise in rates of resistance among enterococci (such as vancomycin-resistant enterococci [VRE]) has been observed as well (13, 18), with VRE accounting for at least 16% of all nosocomial enterococcal infections (15).

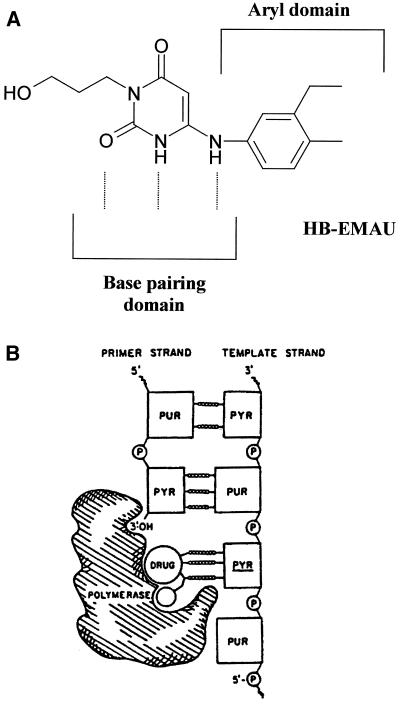

New antibacterial targets and agents are needed to combat this growing antibiotic resistance problem. A promising and unexploited target is replication-specific DNA polymerase IIIC (Pol IIIC), an enzyme product of the polC gene (8, 17). Pol IIIC is found only in Gr+ bacteria with low G+C contents, including Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, Streptococcus, Bacillus, and Listeria species (3, 12). This enzyme is not found in Gr+ bacteria with high G+C contents such as Mycobacterium and Corynebacterium species or in any of the gram-negative (Gr−) organisms (12). We have targeted Pol IIIC for three reasons. First, it is essential for bacterial DNA replication; when its action is blocked, chromosomal DNA fails to replicate and the bacterium dies. Accordingly, Pol IIIC inhibitors are bactericidal (20, 24). Second, the structure of Pol IIIC is highly conserved among Gr+ bacteria (12), suggesting that an effective Pol III inhibitor would display activity against a broad array of clinically relevant Gr+ pathogens. Third, the active site of Pol IIIC is unique in that it has been shown to bind specifically to the small-molecule inhibitors of the 6-anilinouracil (AU) family of inhibitors (6). The AUs act through their capacity to mimic the guanine moiety of dGTP by forming base pairs with an unpaired cytosine on the DNA template (Fig. 1A). The aryl domain of AUs is available to bind to Pol IIIC; the domain then sequesters the enzyme into a nonproductive complex with template primer DNA (5) (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Mechanisms of action of AU compounds. (A) Structure of HBEMAU with base pairing and aryl domains indicated. (B) Schematic of the inactive complex formed by the AU compounds with the polymerase and DNA template-primer.

AU compounds with N3 substitutions such as N3-hydroxybutyl 6-(3′-ethyl-4′-methylanilino) uracil (HBEMAU; Fig. 1A), are being pursued as new antimicrobial agents because of their desirable properties (21). First, they are highly specific inhibitors of Pol IIIC but inhibit DNA polymerase IIIE from Gr+ organisms only at a low level and do not inhibit Pol IIIE from Gr− organisms or polymerase alpha from mammalian sources (20). Second, they are potent antibacterial agents against all Gr+ organisms tested, including a number of antibiotic-resistant clinical isolates such as MRSA strains and VRE (9, 20). Third, they are bactericidal at concentrations one to four times their MICs (9). Finally, they exhibit selectivity for growth of Gr+ pathogens versus mammalian cells, with 50% inhibitory concentrations for a variety of mammalian lines being from 8- to 64-fold greater than the MICs for the pathogens (Microbiotix, Inc., unpublished observations).

As more potent inhibitors of the N3-substituted AU family are discovered, it becomes imperative to judge compounds according to the level of resistance development in S. aureus and Enterococcus species. Knowledge of how antibiotic resistance develops is essential to designing variants of a pharmacophore which have minimal liability for generating resistance. We report here on the frequencies of single-step mutations for resistance to HBEMAU compared to the frequencies of resistance to commercial antibiotics for a panel of Gr+ organisms. In addition, resistant Pol IIIC enzymes were sequenced and purified for an analysis of single-site amino acid changes.

(The results presented here were also presented in part at the 41st Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Chicago, Ill., 2001 [M. M. Butler, D. J. Skow, R. Stephenson, P. J. Lyden, W. A. LaMarr, and K. Foster, 41st Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 139, 2001].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, media, and antimicrobial drugs.

Five Gr+ strains were selected for resistance analysis. The S. aureus Smith strain (ATCC 13709) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, Va.). Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212) was also purchased from ATCC. MRSA, Enterococcus faecium, and VRE were clinical isolates that were kindly provided by Neal C. Brown, University of Massachusetts Medical School. B. subtilis BD54 was the standard laboratory strain (17), and Neal C. Brown provided a B. subtilis strain with the polC27 mutation. All Staphylococcus and Bacillus strains were grown in Luria broth (Difco, Detroit Mich.), and all Enterococcus strains were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco). Antimicrobial drugs were obtained as follows: gentamicin, rifampin, norfloxacin, and vancomycin were from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo.); and ciprofloxacin was from Mediatech, Inc. (Herndon, Va.). DNA primers for PCR were synthesized by Gene Link (Hawthorne, N.Y.).

MIC determinations.

Each antimicrobial drug (commercial drug or AU compound) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and added to one well of a 96-well microassay plate at a concentration of 2,000 or 20 μg/ml, depending on the expected MIC. Twofold serial drug dilutions were made across the plate in DMSO to yield 11 concentrations; in addition, an untreated control was included. The drugs were then transferred to fresh plates at 1.5 μl per well with an electronic multichannel pipette (Matrix, Hudson, N.H.). Log-phase cultures were diluted to yield a concentration of 105 CFU/ml in either Luria broth or BHI medium and transferred to the plates containing drug for a final volume of 150 μl. Each well, including the DMSO controls, contained a final concentration of 1% DMSO. The plates were incubated with shaking at 37°C for 16 to 18 h. Cell growth was determined by measuring the optical density (570 nm; path length, 1 cm) in a microplate reader (Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, Va.). The MICs for the antimicrobial drug-treated cultures were the lowest concentration of drug at which growth was not apparent (less than 25% of the growth for the DMSO control).

Resistance frequency determinations.

The frequencies of single-step spontaneous mutations in five bacterial strains were determined. Log-phase bacteria at a concentration of 106 to 1010 CFU were plated onto BHI agar plates containing drug at eight times the MIC of each drug, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h. In addition, several dilutions of each culture were plated on drug-free media in order to provide accurate colony counts. Resistance frequencies were calculated by dividing the number of colonies growing on antibiotic plates by the total number of CFU plated (10). Each experiment was performed in triplicate on separate days, and mutation frequencies represent average values. In order to verify the stability of each resistant organism, the organisms were transferred several times in drug-free medium and medium containing drug at eight times the MIC and were again tested for resistance.

Isolation of HBEMAU-resistant organisms.

HBEMAU-resistant S. aureus and E. faecalis colonies were isolated and tested for target-specific (i.e., polymerase) resistance. The MICs of a variety of AU inhibitors and commercially available antibiotics for all isolated colonies were determined (as described above). Those isolates that were resistant to HBEMAU (i.e., isolates for which the MICs were at least eightfold greater than that for the wild type) and additional AU compounds, but not to other types of antibiotics, were selected for further analysis.

Purification of native wild-type and HBEMAU-resistant Pol IIIC from Bacillus subtilis, S. aureus, and E. faecalis.

Pol IIIC enzymes were purified from native organisms by a modified version of a previously described method (2). Wild-type and HBEMAU-resistant B. subtilis isolates were included in this study because purification and analysis of the enzymes from these organisms have been well characterized (4, 11). Briefly, cultures were grown at 37°C in BHI medium to an optical density of 1 (600 nm; path length, 1 cm) and harvested by centrifugation at 4,600 × g (15,000 × g for S. aureus) for 15 min at 4°C. The cell pellets were resuspended in standard buffer (20 mM Tris acetate [pH 8.2], 0.5 mM EDTA, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 20 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and lysed by passage through an Aminco French pressure cell (Thermo Spectronic, Rochester, N.Y.) at 20,000 lb/in2. The lysate was briefly sonicated with a Virsonic sonicator (The Virtis Company, Inc., Gardiner, N.Y.) with a medium probe at setting 6 for three 30-s pulses. The lysate was then centrifuged at 40,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. The supernatant was mixed with ammonium sulfate (0.5 g per ml) and stirred at 4°C for 30 min. After centrifugation at 40,000 × g for 30 min, the pellet was dissolved in standard buffer plus 20% glycerol and applied to a Sephadex G-25 column (Sigma Aldrich) that had been equilibrated with GAPE buffer (20% glycerol, 200 mM ammonium sulfate, 10 mM potassium phosphate [pH 6.5], 0.5 mM EDTA, 20 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). After the void volume was removed, the desalted protein was eluted with 0.5 column volumes of GAPE buffer. The protein solution was eluted across a DEAE cellulose column (DE52; Whatman, Clifton, N.J.) to remove contaminating DNA. The DE52 column was equilibrated with GAPE buffer and subsequently eluted with GAPE buffer. Further desalting was achieved by application to a second Sephadex G-25 column equilibrated with weak buffer (20% glycerol, 50 mM potassium phosphate [pH 6.5], 20 mM 2-mercaptoethanol), followed by elution with weak buffer. Separation of Pol IIIC from the other replication-specific polymerase found in Gr+ organisms, Pol IIIE, was attained by application to a second DE52 column. The column was equilibrated with weak buffer, protein was applied, and the column was washed with the same buffer. A linear gradient of 0.05 to 0.6 M phosphate in weak buffer was applied to the column, and fractions were collected and assayed as described below. The first peak containing polymerase activity was identified as Pol IIIE (the other replication-specific polymerase found in Gr+ organisms [24]) by Western analysis with an anti-Pol IIIE antibody (see below), while the second peak contained a mixture of Pol IIIC and Pol I (Pol I is the native polymerase responsible for DNA repair [16]). Pol IIIC from the second DE52 peak was further purified from Pol I by application to a Mono-Q column (Pharmacia, Peapack, N.J.) with a Waters (Milford, Mass.) M-45 high-pressure liquid chromatography pump. The peak was first desalted by application to a G-25 column equilibrated with weak buffer and elution with the same buffer. The desalted material was then applied to the Mono-Q column that had been equilibrated with phosphate buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.5], 20% glycerol, 2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). After the column was washed with phosphate buffer, a linear gradient of 0 to 1 M NaCl in phosphate buffer was applied. Fractions were collected and assayed as described below. Pol I eluted prior to elution of the peak identified as Pol IIIC by Western analysis with a Pol IIIC-specific antibody (see below) and HBEMAU inhibition polymerase assays.

Pol IIIC assay.

DNA polymerase activity was measured in a 96-well plate format. Each 25-μl assay mixture contained 30 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 10 mM magnesium acetate, 4 mM dithiothreitol, and 20% glycerol, with 25 μM dATP, dCTP, and dGTP, 10 μM dTTP (labeled with 3H at 1.44 Ci/mmol), and 0.4 mg of activated calf thymus DNA per ml as substrates, as described previously (2). Reactions were initiated by the addition of 0.025 to 0.06 U of enzyme (1 U is the amount required to incorporate 250 pmol of [3H]dTMP in a standard assay), and the mixture was incubated for 10 min at 30°C. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 100 μl of cold 10% trichloroacetic acid and 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate. Precipitated 3H-labeled DNA was collected on glass fiber filter plates (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.), washed with cold 1 M HCl-100 mM sodium pyrophosphate and then cold 90% ethanol, and dried. The incorporated radioactivity was measured by scintillation counting in a MicroBeta Trilux instrument (Perkin-Elmer Wallac, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) in the presence of OptiPhase Supermix (Perkin Elmer Wallac, Inc.). Apparent inhibitor constants (Kis) were determined directly by a truncated assay in the absence of dGTP as described previously (23). The activities of the purified enzyme fractions were measured by using all four deoxynucleoside triphosphates in the reaction mixtures.

Identification of Pol IIIE and Pol IIIC by Western blot analysis.

Peak fractions were denatured and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with PAGEr precast gels (BioWhittaker Molecular Applications, Rockland, Maine) with a 4 to 20% gradient. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes at 100 V in transfer buffer (200 mM glycine, 25 mM Tris base, 20% methanol) at 4°C for 2 h. Blocking was completed by incubation with blocking buffer (2% nonfat milk, TBST [100 mM Tris {pH 7.5}, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20]) at 4°C overnight. Membranes were incubated with polyclonal antibodies (either anti-Pol IIIC or anti-Pol IIIE) in blocking buffer at room temperature for 1 h. The membranes were then washed five times (10 min each) with TBST prior to application of the secondary antibody. Anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Promega, Madison, Wis.) was applied to the membranes in blocking buffer at room temperature for 1 h. The membranes were washed 10 times (10 min each) with TBST. SuperSignal chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) was applied for 1 min, and the membranes were subsequently developed by using BioMax film (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, N.Y.).

Cloning and sequencing of wild-type and HBEMAU-resistant Pol IIIC.

E. faecalis genomic DNA was purified with a Dneasy tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). The polC gene was amplified by PCR with the Taq PCR master mix kit (Qiagen). A 27-mer (GCGATTTATTTCTCGAGCTGATGACGC) containing an XhoI restriction site (underlined) and the ATG start sequence (in boldface) was used to prime the sequence upstream of the polC gene. A 31-mer downstream of the stop codon (ATTCACAACATTTCCGGATCCCCAGACCATG) containing a BamHI restriction site (underlined) was used to prime the sequence downstream of the polC gene. The resulting PCR product was digested with XhoI and BamHI and inserted into pBluescript SK(+) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) that had previously been digested with XhoI and BamHI.

The S. aureus polC gene was amplified by PCR and cloned as described above for E. faecalis polC by using as primers an upstream 26-mer (GGTGGTCTCGAGCTTGGCAATGACAG) and a downstream 30-mer (GGTATTGGATCCACTACGCCATACGCATTA). These primers successfully amplified the polC gene.

Plasmid DNA was prepared for sequencing by using the Plasmid Midi kit (Qiagen). Automated DNA sequencing was performed (Davis Sequencing, Davis, Calif.), and the DNA sequence was translated to the amino acid sequence by using Sequencher software (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, Mich.). Sequence data for wild-type and resistant B. subtilis polC isolates have been published previously (11).

RESULTS

Determination of frequencies of resistance to HBEMAU and commercially available antibiotics.

Table 1 summarizes the frequencies of occurrence of mutations resulting in resistance to HBEMAU and three commercially available antibiotics, rifampin, gentamicin, and ciprofloxacin, which were used for comparison. Following determination of the MICs, the frequencies of resistance to the antibiotics at eight times the MIC were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The frequencies of resistance to rifampin were from 8 × 10−7 to 9 × 10−8, with the highest frequencies occurring for MRSA and VRE. Higher frequencies of resistance to gentamicin were observed for S. aureus and E. faecalis (1 × 107 to 8 × 107). Frequencies of resistance were not determined for the three remaining organisms due to the high MICs of gentamicin for the strains. The frequencies of resistance to HBEMAU as well as ciprofloxacin for all organisms were lower than the frequencies of resistance to rifampin and gentamicin. The frequencies of resistance to HBEMAU ranged from 1 × 10−9 to 1 × 10−10 for all strains except the strain of VRE, for which the frequency was 1.2 × 10−8. The frequencies of resistance to ciprofloxacin were in the range of 10−10 for all strains with the exception of the strain of VRE, for which the frequency of resistance was 4.3 × 10−8. The frequencies of resistance to HBEMAU were less than those to rifampin and gentamicin and were equivalent to those to ciprofloxacin.

TABLE 1.

Frequency of single-step mutations for five Gr+ organisms

| Strain and drug | Single-step mutation frequencya | |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus (Smith) | ||

| HBEMAU | 7.3 × 10−10 | |

| Rifampin | 9 × 10−8 | |

| Gentamicin | 1 × 10−7 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 8.2 × 10−10 | |

| MRSA 1094 | ||

| HBEMAU | 5.9 × 10−9 | |

| Rifampin | 8 × 10−7 | |

| Gentamicin | NDb | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 2.2 × 10−10 | |

| E. faecalis | ||

| HBEMAU | 8.4 × 10−9 | |

| Rifampin | 2 × 10−8 | |

| Gentamicin | 4 × 10−8 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | <1.1 × 10−10 | |

| E. faecium | ||

| HBEMAU | 3.6 × 10−10 | |

| Rifampin | 8 × 10−8 | |

| Gentamicin | ND | |

| Ciprofloxacin | <1.7 × 10−10 | |

| VRE B24762 | ||

| HBEMAU | 1.2 × 10−8 | |

| Rifampin | 4 × 10−8 | |

| Gentamicin | ND | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 4.3 × 10−8 |

Frequency of mutation was determined as described in Materials and Methods by using each drug at eight-fold the MIC.

ND, not determined due to the insolubility of drug at eight times the MIC.

Isolation of S. aureus and E. faecalis HBEMAU-resistant colonies.

Resistant S. aureus and E. faecalis colonies (i.e., those for which the MICs were at least eightfold greater than the MICs for the wild-type isolates) were isolated to determine the mechanism of resistance conferred by the mutation. Cultures of HBEMAU-resistant S. aureus and E. faecalis strains were isolated from their respective drug plates and grown several times on drug-free media. To investigate the source(s) of the HBEMAU-resistant phenotypes (i.e., a target-specific or target-independent alteration), the MICs of both commercially available antibiotics and the AU compounds were determined. The MICs of commercial antibiotics were determined so that general efflux and cell permeability mutations could be identified. Several AU compounds were included in the analysis in order to determine whether the mutation was specific to HBEMAU or included reduced susceptibility to other HBEMAU analogs: methoxybutyl-EMAU and hydroxyoctyl-EMAU [EMAU is (3′-ethyl-4′-methylanilino) uracil]. All wild-type organisms were equally sensitive to HBEMAU and the analogs (MIC range, 3 to 6 μg/ml), while all the resistant organisms were fully resistant to the AU compounds (MICs, >80 μg/ml). These results suggest the presence of target-specific mutations in the resistant organisms. In addition, analysis of the rifampin, gentamicin, norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and vancomycin MICs for HBEMAU-sensitive and -resistant organisms showed no change in antibiotic susceptibilities.

Isolation and inhibitor-based analysis of HBEMAU-resistant Pol IIIC enzymes.

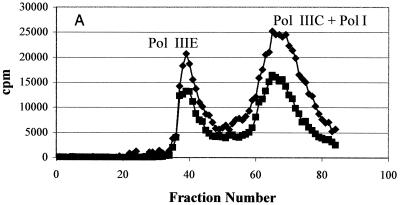

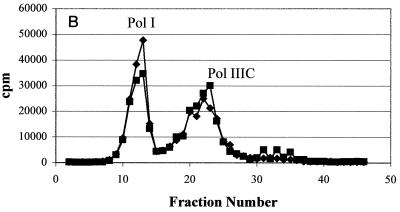

In order to account for the resistance observed in the whole bacteria, Pol IIIC preparations from wild-type and HBEMAU-resistant organisms were isolated as detailed in Materials and Methods by using wild-type and HBEMAU-resistant B. subtilis isolates as controls. The identity of wild-type Pol IIIC was determined by measuring the HBEMAU-inhibitable activities of the fractions obtained by chromatography. As can be seen in Fig. 2A, separation of wild-type S. aureus Pol IIIC from the other replication-specific polymerase, Pol IIIE, was attained following two rounds of DE52 chromatography. The first column (data not shown) served to remove contaminating DNA. The second DE52 column (Fig. 2A), eluted with a phosphate gradient, separated Pol IIIE from Pol IIIC, but Pol I continued to coelute with Pol IIIC. HBEMAU inhibition of this peak was approximately 53% due to the presence of the contaminating Pol I enzyme, which is insensitive to HBEMAU. The peak identified as containing Pol IIIE was only somewhat sensitive to 250 μM HBEMAU (inhibition, approximately 33%). This observation was reasonable since the 50% inhibitory concentration of HBEMAU for Pol IIIE is quite high (approximately 700 μM). Separation of Pol IIIC from Pol I was achieved with a Mono-Q ion-exchange column (Fig. 2B). As expected, Pol IIIC isolated from the wild-type organism was inhibited approximately 99% by 250 μM HBEMAU, while Pol IIIE and Pol I were either slightly inhibited or not inhibited at all by the same concentration of HBEMAU.

FIG. 2.

Purification of wild-type S. aureus Pol IIIC from the native organism. Points represent DNA polymerase activity. (A) DEAE cellulose column purification; (B) Mono-Q column purification. ♦, DMSO control; ▪, with 250 μM HBEMAU.

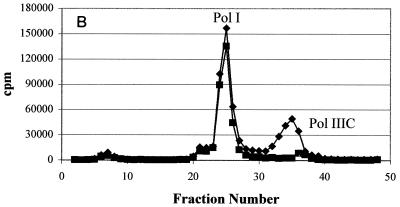

An identical methodology was used to isolate Pol IIIC from HBEMAU-resistant S. aureus (Fig. 3). Similar to the results for wild-type S. aureus, DE52 chromatography successfully separated Pol IIIC from Pol IIIE, but Pol I continued to coelute with Pol IIIC (Fig. 3A). No inhibition of the enzyme with this combined peak was observed because Pol IIIC was no longer sensitive to HBEMAU. As seen in Fig. 3B, Mono-Q chromatography clearly separated the Pol I and Pol IIIC enzymes in the resistant mutant. However, unlike the wild-type Pol IIIC, the Pol IIIC from the resistant mutant was not inhibited by HBEMAU and thus could not be identified by its sensitivity to HBEMAU.

FIG. 3.

Purification of HBEMAU-resistant S. aureus Pol IIIC from the native organism. Points represent DNA polymerase activity. (A) DEAE cellulose column purification; (B) Mono-Q column purification. ♦, DMSO control; ▪, with 250 μM HBEMAU.

Identification of the purified enzyme fractions was achieved by immunoblot analysis with polyclonal antibodies against either B. subtilis Pol IIIC or B. subtilis Pol IIIE (data not shown). The B. subtilis antibodies were cross-reactive to the corresponding enzymes in S. aureus and E. faecalis. In addition, the anti-Pol IIIC antibody reacted with the mutant Pol IIIC enzymes, permitting identification of enzymes that were no longer sensitive to HBEMAU.

An identical purification methodology was used to successfully isolate both wild-type and HBEMAU-resistant Pol IIIC enzyme fractions from B. subtilis and E. faecalis (data not shown). Inhibition assays with HBEMAU were performed with each of the six purified Pol IIIC enzymes. As Table 2 demonstrates, the Ki values for all three wild-type Pol IIIC enzymes were in the submicromolar range, as expected. Accordingly, the Ki values for the resistant enzymes were more than 1,000-fold higher than those for their wild-type counterparts. The results of these enzyme isolation studies suggest that the HBEMAU resistance observed is the result of a modification of the Pol IIIC enzyme. Sequencing of the polC gene from each organism was done to definitively prove that Pol IIIC was mutated and to identify the specific site of the mutation in the genome.

TABLE 2.

HBEMAU Ki values for wild-type versus resistant Pol IIIC

| Purified Pol IIIC |

Kia (μM) of HBEMAU

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | HBEMAU resistant | |

| B. subtilis | 0.22 | 520 |

| S. aureus | 0.29 | 780 |

| E. faecalis | 0.23 | 980 |

Ki values were determined in a truncated assay without dGTP as described in Materials and Methods.

Cloning and sequencing of HBEMAU-resistant polC.

Further analysis of HBEMAU-resistant organisms included a search for the source of the mutation, presumably located in the DNA of the Pol IIIC enzyme encoded by the polC gene. Cloning of the S. aureus and E. faecalis polC genes was performed by PCR amplification of genomic DNA with primers that flanked the polC-coding sequence. The upstream primer contained an XhoI restriction site, while the downstream primer contained a BamHI restriction site. Digestion of the amplified DNA with XhoI and BamHI allowed the gene to be placed in a similarly cut sequencing vector. PolC DNA from both organisms were sequenced in their entirety by using overlapping primers. As indicated in Table 3, the only mutation that appeared in all HBEMAU-resistant S. aureus and E. faecalis isolates was a change in amino acid 1264 (for B. subtilis and E. faecalis) or its homologue, amino acid 1261 (for S. aureus). The B. subtilis polC27 mutant was described previously (11) and was a kind gift from Neal C. Brown. It was included for comparison purposes. In all three organisms, the conserved phenylalanine that is known to be located in the drug-binding pocket of B. subtilis (4) was mutated to one of three possible amino acids, serine, isoleucine, or leucine. Interestingly, only that one amino acid was found to be altered in the seven mutant isolates of each organism analyzed.

TABLE 3.

Prediction of protein sequences of HBEMAU-resistant organismsa

| Organism | Amino acid mutation site | Amino acid in:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type strain | Resistant strain | ||

| B. subtilis polC27b | 1264 | Phenylalanine | Serine |

| E. faecalis mutant 1 | 1264 | Phenylalanine | Isoleucine |

| E. faecalis mutant 2 | 1264 | Phenylalanine | Leucine |

| S. aureus | 1261 | Phenylalanine | Leucine |

The protein sequence was predicted by sequencing the polC DNA of mutant organisms and comparing the sequence to the known amino acid sequences of wild-type Pol IIIC enzymes.

First described in reference 11.

DISCUSSION

An important parameter in the development of antimicrobial drugs is the degree of resistance observed in the target organisms. We have examined the frequencies of single-step mutations for resistance to our AU prototype HBEMAU with a number of Gr+ organisms. The frequencies of mutations for resistance to HBEMAU were lower than the frequencies of mutations for resistance to rifampin and gentamicin, which were in the range of 10−7 to 10−8. They were nearly equivalent to the frequencies of mutations for resistance to ciprofloxacin. Previously reported (10, 14) frequencies of single-step mutations for resistance to ciprofloxacin (at eight times the MIC) for strains of methicillin-susceptible S. aureus and MRSA ranged from 1.3 × 10−8 to less than 4.5 × 10−11. The values reported here for frequencies of mutations for resistance to ciprofloxacin are well within the range of those reported in the literature. This exercise has been important to the development of a method to test the frequencies of mutations for resistance to promising new compounds emerging from the AU family.

Analysis of the MICs for both HBEMAU-sensitive and -resistant organisms suggested that each of the mutations was target specific. In other words, each resistant isolate was resistant only to the AU compounds and not to commercially available antibiotics representing the rifamycin, aminoglycoside, fluoroquinolone, and glycopeptide families. The data appear to be consistent with a target-specific mechanism of action, which is confirmed by the sequence analysis and the enzymology studies. One would expect to obtain non-target-related changes such as uptake, efflux, or drug metabolism mutations. The fact that the MICs of five unrelated antibiotics remained unchanged points against this possibility.

The next logical step in this study was to isolate the putative target (Pol IIIC) encoded by the resistance mutation in the polC gene. Mutants of B. subtilis polC have been described previously (11) and were available for use as a reference. Growth of wild-type and resistant S. aureus and E. faecalis cultures and purification of Pol IIIC from these native (nonrecombinant) sources was accomplished successfully. The altered Pol IIIC enzymes displayed as much polymerase activity as their wild-type counterparts. Inhibition or Ki analysis with purified wild-type Pol IIIC enzymes demonstrated that HBEMAU is as potent against wild-type S. aureus and E. faecalis enzymes as it is against the reference enzyme from B. subtilis. Not unexpectedly, all three enzymes isolated from HBEMAU-resistant hosts had very high Ki values for HBEMAU. The ratio between the Ki values of HBEMAU-resistant and wild-type strains ranged from 2,200 to 3,400 for the three organisms tested. This clearly accounts for the >13- to 26-fold differences in the MICs for these resistant organisms. Higher MIC ratios could not be observed due to limits in drug solubility.

Sequencing of the polC gene in this study has shown, as in previous studies, that a common change associated with AU resistance is Phe1264→Leu, Ile, or Ser. This amino acid (located at position 1261 in S. aureus Pol IIIC) is positioned within the known inhibitor or aryl binding region encompassed by amino acids 1175 to 1273 (4). This region of AU-resistant B. subtilis isolates contains at least four amino acids whose DNA sequences are known to be altered (4). An analysis of the seven mutants isolated from each organism showed that only position 1264 (position 1261 in S. aureus) contained changes (data not shown). Previous studies have shown that transformation of the mutant polC gene (polC27) back into the chromosome of a sensitive parent strain of B. subtilis imparts comparable levels of resistance to the AU compounds (11). This further supports the suggestion that the Pol IIIC enzyme encoded by polC is the sole target of the AU compounds and that its mutation is responsible for resistance.

The AU family of selective inhibitors of Pol IIIC has been exploited, both here and in the past, to demonstrate that Pol IIIC of Gr+ organisms is, indeed, a valid antibiotic target. The AU compounds are effective against many pathogenic strains of S. aureus and Enterococcus species, including antibiotic-resistant organisms (9, 20). In addition, they are protective against lethal staphylococcal infections in vivo (20). In the system used here, resistance in general populations of bacteria was less likely to develop after the use of HBEMAU than after the use of rifampin and gentamicin and was no more likely to develop after the use of HBEMAU than after the use of ciprofloxacin. The results presented here suggest that further study of HBEMAU and its successors is warranted.

Acknowledgments

We thank Neal C. Brown for providing bacterial strains and many helpful discussions.

This work was supported by Shire BioChem, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aeschlimann, J. R., E. Hershberger, and M. J. Rybak. 1999. Analysis of vancomycin population susceptibility profiles, killing activity, and postantibiotic effect against vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1914-1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes, M. H., and N. C. Brown. 1979. Antibody to B. subtilis DNA polymerase III: use in the purification of enzyme and the study of its structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 6:1203-1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes, M. H., C. Leo, and N. C. Brown. 1998. DNA polymerase III of gram-positive eubacteria is a zinc metalloprotein conserving an essential finger-like domain. Biochemistry 37:15254-15260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes, M. H., R. A. Hammond, C. C. Kennedy, S. L. Mack, and N. C. Brown. 1992. Localization of the exonuclease and polymerase domains of Bacillus subtilis DNA polymerase III. Gene 111:43-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, N. C., J. J. Gambino, and G. E. Wright. 1977. Inhibitors of Bacillus subtilis DNA polymerase III. 6-(arylalkylamino) uracils and 6-anilinouracils. J. Med. Chem. 20:1186-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, N. C., L. W. Dudycz, and G. E. Wright. 1986. Rational design of substrate analogues targeted to selectively inhibit replication-specific DNA polymerases. Drugs Exp. Clin. Res. 12:555-564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002. Staphylococcus aureus resistant to vancomycin—United States. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. [Online.] http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5126a1.htm.

- 8.Cozzarelli, N. R. 1977. The mechanism of action of inhibitors of DNA synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 46:641-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daly, J. S., T. J. Giehl, N. C. Brown, C. Zhi, G. E. Wright, and R. T. Ellison III. 2000. In vitro antimicrobial activities of novel anilinouracils which selectively inhibit DNA polymerase III of gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2217-2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans, M. E., and W. B. Titlow. 1998. Selection of fluoroquinolone-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with ciprofloxacin and trovafloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gass, K. B., and N. R. Cozzarelli. 1973. Further genetic and enzymological characterization of the three Bacillus subtilis deoxyribonucleic acid polymerases. J. Biol. Chem. 248:7688-7700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang, Y.-P., and J. Ito. 1998. The hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima has two different classes of family C DNA polymerases: evolutionary implications. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:5300-5309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huycke, M. M., D. F. Sahm, and M. S. Gilmore. 1998. Multiple-drug resistant enterococci: the nature of the problem and an agenda for the future. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 4:239-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ince, D., and D. C. Hooper. 2000. Mechanisms and frequency of resistance to premafloxacin in Staphylococcus aureus: novel mutations suggest novel drug-target interactions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3344-3350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones, R. N., and M. A. Pfaller. 1998. Bacterial resistance: a worldwide problem. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 31:379-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kornberg, A., and T. A. Baker. 1992. DNA replication. W. H. Freeman & Co., New York, N.Y.

- 17.Love, E., J. D'Ambrosio, N. C. Brown, and D. Dubnau. 1976. Mapping of the gene specifying DNA polymerase III of B. subtilis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 144:313-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michel, M., and L. Gutmann. 1997. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci: therapeutic realities and possibilities. Lancet 349:1901-1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Small, P. M., and H. F. Chambers. 1990. Vancomycin for Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis in intravenous drug users. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:1227-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarantino, P. M., C. Zhi, G. E. Wright, and N. C. Brown. 1999. Inhibitors of DNA polymerase III as novel antibacterial agents against gram-positive eubacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1982-1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarantino, P. M., C. Zhi, J. J. Gambino, G. E. Wright, and N. C. Brown. 1999. 6-Anilinouracil-based inhibitors of Bacillus subtilis DNA polymerase III: antipolymerase and antimicrobial structure-activity relationships based on substitution at uracil N-3. J. Med. Chem. 42:2035-2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomasz, A. 1994. Multiple-antibiotic-resistant bacteria. N. Engl. J. Med. 330:1247-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wright, G. E., and N. C. Brown. 1976. The mechanism of inhibition of B. subtilis DNA polymerase III by 6-(arylhydrazino) pyrimidines: novel properties of 2-thiouracil derivatives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 432:37-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright, G. E., and N. C. Brown. 1999. DNA polymerase III: a new target for antibiotic development. Curr. Opin. Anti-Infect. Investig. Drugs 1:45-48. [Google Scholar]