Abstract

We describe the development of chimeric virus technology (CVT) for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 (HIV-1) env genes gp120, gp41, and gp160 for evaluation of the susceptibilities of HIV to entry inhibitors. This env CVT allows the recombination of env sequences derived from different strains into a proviral wild-type HIV-1 clone (clone NL4.3) from which the corresponding env gene has been deleted. An HIV-1 strain (strain NL4.3) resistant to the fusion inhibitor T20 (strain NL4.3/T20) was selected in vitro in the presence of T20. AMD3100-resistant strain NL3.4 (strain NL4.3/AMD3100) was previously selected by De Vreese et al. (K. De Vreese et al., J. Virol. 70:689-696, 1996). NL4.3/AMD3100 contains several mutations in its gp120 gene (De Vreese et al., J. Virol. 70:689-696, 1996), whereas NL4.3/T20 has mutations in both gp120 and gp41. Phenotypic analysis revealed that NL4.3/AMD3100 lost its susceptibility to dextran sulfate, AMD3100, AMD2763, T134, and T140 but not its susceptibility to T20, whereas NL4.3/T20 lost its susceptibility only to the inhibitory effect of T20. The recombination of gp120 of NL4.3/AMD3100 and gp41 of NL4.3/T20 or recombination of the gp160 genes of both strains into a wild-type background reproduced the phenotypic (cross-)resistance profiles of the corresponding strains selected in vitro. These data imply that mutations in gp120 alone are sufficient to reproduce the resistance profile of NL4.3/AMD3100. The same can be said for gp41 in relation to NL4.3/T20. In conclusion, we demonstrate the use of env CVT as a research tool in the delineation of the region important for the phenotypic (cross-)resistance of HIV strains to entry inhibitors. In addition, we obtained a proof of principle that env CVT can become a helpful diagnostic tool in assessments of the phenotypic resistance of clinical HIV isolates to HIV entry inhibitors.

The treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection used at present focuses primarily on inhibition of the viral enzymes reverse transcriptase (RT) and protease (PRO). These compounds are not always able to suppress virus replication completely. In many patients, residual replication in the presence of the selective pressure of antiviral drugs allows the emergence of drug-resistant strains, finally resulting in therapeutic failure (19, 28). Therefore, the development of new drugs that preferentially act on new targets in the HIV replication cycle is of high priority in anti-HIV research. A potentially powerful target in addition to RT and PRO is the first event in the virus replicative cycle, HIV entry. HIV entry involves the interaction of the viral protein gp120 with the CD4 receptor on the surface of the target cell and the subsequent interaction of gp120 with the coreceptor CCR5 (for strains using the CCR5 receptor) or CXCR4 (for strains using the CXCR4 receptor). This interaction results in a conformational change in viral glycoprotein gp41, in which the interaction of heptad region 1 (HR1) and HR2 is followed by fusion of the virus with the cellular lipid bilayer (6).

Several compounds that inhibit viral entry have been described. These molecules act at different stages of HIV entry. Typical polyanionic structures like dextran sulfate (DS) (3) inhibit the binding of gp120 to CD4 by blocking the interaction of the positively charged V3 loop of gp120 with the negatively charged cell surface. HIV coreceptor antagonists have also been described as HIV inhibitors. TAK-779 has recently been reported to be a potent and selective inhibitor of R5 strain replication (4). Several polycationic molecules were found to interact electrostatically with the negatively charged amino acid residues of the CXCR4 receptor. The most promising CXCR4 antagonists are the low-molecular-weight bicyclams AMD3100 and AMD2763 (8, 9, 12, 13, 25). AMD3100 not only inhibits the replication of X4 strains but may also prevent the switch from the less pathogenic R5 HIV strains to the more pathogenic X4 HIV strains (14). Thus, the blockade of the emergence of X4 variants is an interesting strategy in anti-HIV therapy. The bicyclam AMD3100 was introduced in phase II clinical trials (30), but development was interrupted due to cardiac problems. The synthetic peptide T22, an 18-mer (22), and its shortened successors T134 and T140 (2, 26, 27) act as CXCR4 antagonists due to their positive charges.

Other inhibitors of viral entry interact with the fusion process itself. T20 is a synthetic peptide segment consisting of 36 amino acids within the C-terminal heptad repeat region (HR2) of gp41. The mechanism of T20 is proposed to be an interaction with a target sequence within HR1, which therefore prevents apposition of the viral and cellular membranes. Phase III studies comparing the antiretroviral activities of T20-containing regimens in adult patients in the context of an optimized background regimen are under way (B. Clotet, A. Lazzarin, D. Cooper, J. Reynes, K. Arastey, M. Nelson, C. Katlama, J. Chung, L. Fang, J. Delehante, and M. Salgo, Abstr. XIV Int. AIDS Conf., abstr. LbOr19A, 2002).

We have now developed env chimeric virus technology (CVT) (for which a patent has been filed), based on the principle of the recombinant virus assay, which was originally developed to evaluate the susceptibilities of clinical isolates to RT and/or PRO inhibitors. This technique is based on the homologous recombination of an amplified patient-derived HIV type 1 (HIV-1) RT and/or PRO gene into a laboratory HIV-1 proviral clone from which the RT and/or PRO gene was deleted (16, 18, 20). The resulting recombinant virus thus acquires susceptibility to RT and/or PRO inhibitors of the clinical isolate, while the inhibition of the HIV-induced cytopathic effect (CPE) can be measured in a reproducible, rapid, and semiautomated manner. By env CVT, we can insert the mutated env genes of HIV strains selected in the presence of entry inhibitors into the genetic wild-type background of a molecular clone in order to assess the significance of the mutated env genes on the phenotypic resistance of the selected strain. Here, we report on the design and development of the env-based CVT and the application of this technology to HIV-1 NL4.3 strains selected in vitro in the presence of AMD3100 or T20.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds.

DS (average molecular weight, 5,000) was purchased from Sigma (Bornem, Belgium). AMD3100 and AMD2763 were kindly provided by Gary Bridger and Geoffrey Henson (AnorMED, Langley, British Columbia, Canada) and were synthesized as described previously (5). The compounds T134 and T140 (2, 26, 27) were kindly provided by H. Nakashima (Kagoshima University, Japan). 3′-Azido-3′-deoxythymidine (AZT) was synthesized by the method described by Horwitz et al. (17).

Cells.

MT-4 cells (21) were grown and maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.1% sodium bicarbonate, and 20 μg of gentamicin per ml.

Virus strains.

HIV-1 strain NL4.3 is derived from a molecular clone (1) (obtained from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.). The HIV-1 NL4.3 strain resistant to AMD3100 (strain NL4.3/AMD3100) (12, 13) was previously selected in our laboratory after serial passage of HIV-1 NL4.3 in the presence of increasing concentrations of AMD3100. The final concentration of AMD3100 at the end of selection was 50,000-fold the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) for HIV-1 NL4.3 in MT-4 cells, as determined at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01.

PCR amplification and sequencing of different env regions. (i) PCR amplification of gp120-encoding sequences.

MT-4 cells were infected with the HIV laboratory strains selected in vitro in the presence of the entry inhibitor AMD3100 or T20. DNA extraction of proviral DNA was performed with the QIAamp blood kit (Qiagen; Hilden, Germany). A 2,095-bp nucleotide fragment (positions 5550 to 7644) of gp120 was amplified by a nested PCR with the Expand High Fidelity PCR system (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), which is composed of an enzyme mix containing thermostable Taq DNA and Pwo DNA polymerase with a 3′-5′ exonuclease proofreading capacity. The outer PCR was performed on a Gene Amp PCR system 9600 instrument (Perkin-Elmer, Brussels, Belgium), and the inner PCR was performed on a Biometra Trioblock instrument (Westburg) with primers AV310 (5′-AGC AGG ACA TAA YAA GGT AGG-3′, corresponding to positions 5448 to 5468 of NL4.3) and AV311 (5′-CTA CTT TAT AYT TAT ATA ATT CAC TTC TCC-3′, corresponding to positions 7650 to 7679 of NL4.3), followed by primers AV312 (5′-AGA RGA YAG ATG GAA CAA GCC CCA G-3′, corresponding to positions 5550 to 5574 of NL4.3) and AV313 (5′-TCC YTC ATA TYT CCT CCT CCA GGT C-3′, corresponding to positions 7620 to 7644 of NL4.3). The outer cycling conditions were as follows: a first denaturation step of 2 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 50°C, and 2 min at 72°C. A final extension was performed at 72°C for 10 min. For the inner cycling, the following conditions were used: after 2 min at 95°C, 30 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 58°C, and 2 min at 72°C, with a 10-min extension at 72°C.

(ii) Sequencing of gp120-encoding regions.

PCR products were purified with a PCR purification kit (Qiagen). The ABI PRISM Dye terminator cycle sequencing core kit (Perkin-Elmer) was used to carry out the sequencing reaction. The primers used to sequence the entire gp120 gene were primers AV304 (5′-ACA TGT GGA AAA ATG ACA TGG T-3′, corresponding to positions 6501 to 6522 of NL4.3), AV305 (5′-GAG TGG GGT TAA TTT TAC ACA TGG-3′, corresponding to positions 6572 to 6595 of NL4.3), AV306 (5′-TGT CAG CAC AGT ACA ATG TAC ACA-3′, corresponding to positions 6937 to 6960 of NL4.3), AV307 (5′-TCT TCT TCT GCT AGA CTG CCA T-3′, corresponding to positions 6999 to 7020 of NL4.3), AV308 (5′-TCC TCA GGA GGG GAC CCA GAA ATT-3′, corresponding to positions 7304 to 7327 of NL4.3), AV309 (5′-CAR TAG AAA AAT TCY CCT CYA CA-3′, corresponding to positions 7346 to 7368 of NL4.3), and AV313. The samples were loaded onto an ABI PRISM 310 genetic analyzer (Perkin-Elmer). The sequences were analyzed with the software program Geneworks (version 2.5.1; Intelligenetics Inc., Oxford, United Kingdom).

(iii) PCR amplification of gp41-encoding sequences.

A 1,583-bp nucleotide fragment (corresponding to positions 7344 to 8926 of NL4.3) was amplified by PCR with the Expand High Fidelity PCR system. The PCR was performed on a Biometra Trioblock instrument with primers AV320 (5′-ATT GTR GAG GRG AAT TTT TCT ACT G-3′, corresponding to positions 7344 to 7368 of NL4.3) and AV321 (5′ TTG CTAY CTT GTG ATT GCY CCA TG-3′, corresponding to positions 8904 to 8926 of NL4.3). The cycling conditions were as follows: a first denaturation step of 2 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles consisting of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 2 min at 68°C. A final extension was performed at 72°C for 10 min.

(iv) Sequencing of gp41-encoding region.

The primers used to sequence the gp41 gene were AV322 (5′-AAG CAA TGT ATG CCC CTC C-3′, corresponding to positions 7509 to 7527 of NL4.3), AV323 (5′-CTG CTC CYA AGA ACC CAA-3′, corresponding to positions 7771 to 7790 of NL4.3), AV324 (5′-GGC AAA GAG AAG AGT GGT-3′, corresponding to positions 7714 to 7731 of NL4.3), AV326 (5′-TTG GGG YTG CTC TGG AAA AC-3′, corresponding to positions 7999 to 8018 of NL4.3), AV327 (5′-TTT TAT ATA CCA CAG CCA-3′, corresponding to positions 8246 to 8263 of NL4.3), AV328 (5′-ATA ATG ATA GTA GGA GG-3′, corresponding to positions 8270 to 8286 of NL4.3), AV329 (5′-GTC CCA GAA GTT CCA CA-3′, corresponding to positions 8557 to 8573 of NL4.3), AV330 (5′-GGA RCC TGT GCC TCT TCA-3′, corresponding to positions 8496 to 8513 of NL4.3), and AV331 (5′-TCT CAT TCT TTC CCT TA-3′, corresponding to positions 8833 to 8849 of NL4.3).

(v) PCR amplification of gp160-encoding sequences.

A 3,590-bp nucleotide fragment (corresponding to positions 5448 to 9037 of NL4.3) was amplified by PCR with the Expand High Fidelity PCR system. The PCR was performed on a Biometra Trioblock instrument with primers AV310 and AV319 (5′-GCT SCC TTR TAA GTC ATT GGT CT-3′, corresponding to positions 9015 to 9037 of NL4.3). The cycling conditions were as follows: a first denaturation step of 2 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles consisting of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 3 min and 40 s at 68°C. A final extension was performed at 72°C for 10 min.

env recombination assay.

MT-4 cells were subcultured at a density of 500,000 cells/ml 1 day prior to transfection. The cells were pelleted and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline at a concentration of 3.125 × 106 cells/ml. For each transfection, 2.5 × 106 cells (0.8 ml) were used. Transfections were performed by electroporation with an EASYJECT instrument (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium) and electroporation cuvettes (Eurogentec). For the gp120 recombination experiments, MT-4 cells were cotransfected with 10 μg of linearized clone NL4.3 from which gp120 was deleted and 2 μg of the purified and concentrated inner PCR product obtained with primers AV312 and AV313 (PCR purification kit, Qiagen). For the gp41 recombination experiments, the cells were cotransfected with 10 μg of linearized clone NL4.3 from which gp41 was deleted and 2 μg of the purified and concentrated PCR product obtained with primers AV320 and AV321, whereas in the gp160 recombination experiments the PCR product obtained with primers AV310 and AV319 was cotransfected with the clone from which gp160 was deleted. The electroporation conditions used for all transfections were 300 μF and 300 V. After 30 min of incubation at room temperature, the transfected cell suspension was incubated in 5 ml of culture medium at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The recombinant virus was harvested by centrifugation once the full CPE was microscopically observed in the culture (at about 6 days posttransfection). Aliquots of 1 ml were stored at −80°C for subsequent infectivity determinations (50% cell culture infective doses [CCID50s]) and drug susceptibility determinations (IC50s) in the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay with MT-4 cells (23, 29).

Drug susceptibility assay.

The inhibitory effects of the antiviral drugs on the HIV-induced CPE in human lymphocyte MT-4 cell culture was determined by the MTT assay (23, 29). This assay is based on the reduction of the yellow compound MTT by mitochondrial dehydrogenase of metabolically active cells to a blue formazan derivative, which can be measured spectrophotometrically. The CCID50s of the HIV strains were determined by titration of the virus stock with MT-4 cells. For the drug susceptibility assays, MT-4 cells were infected with 100 to 300 CCID50s of the HIV strains in the presence of fivefold serial dilutions of the antiviral drugs. The concentration of the compound that achieved 50% protection against the CPE of HIV, which is defined as the IC50, was determined.

RESULTS

Selection of resistance in HIV-1 NL4.3 in the presence of T20.

An HIV-1 strain (strain NL4.3) displaying resistance to T20 (NL4.3/T20) was selected after serial passage of HIV-1 strain NL4.3 in the presence of increasing concentrations of T20. The selection of resistance was initiated at a low multiplicity of infection (0.01) and a drug concentration fivefold its IC50, as determined in the MTT assay with MT-4 cells (23, 29). Every 3 to 4 days the MT-4 cell culture was monitored for the appearance of an HIV-induced CPE. When a CPE was observed, the cell-free culture supernatant was used to reinfect fresh, uninfected MT-4 cells in the presence of an equal or higher concentration of the compound. When no virus breakthrough was observed, the infected cell culture was subcultivated in the presence of the same concentration of the compound. Gradually, after 40 subsequent passages, the concentration of the compound was significantly increased up to 16 μg/ml. This final concentration was 260-fold higher than the concentration of T20 required to inhibit the replication of wild-type HIV-1 strain NL4.3 (NL4.3WT) by 50% (IC50).

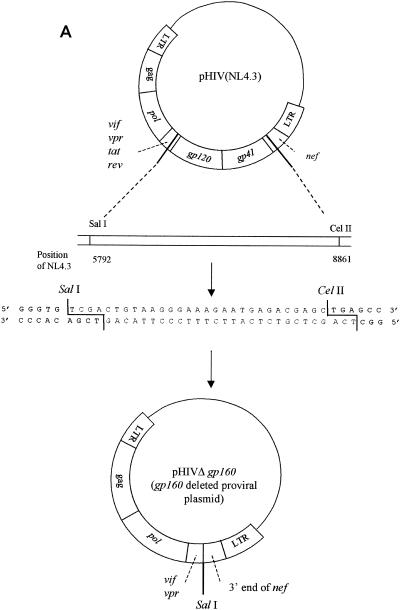

Construction of clones from which different env were deleted.

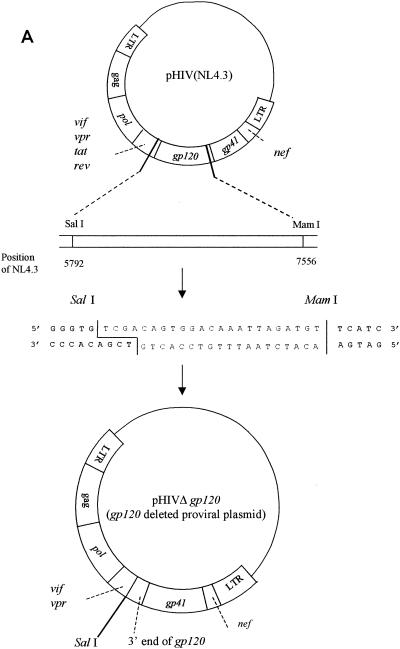

To construct the clone from which gp120 was deleted, proviral molecular clone pNL4.3 (1) was used as the starting material. This clone consists of plasmid pUC18, in which the complete HIV-1 genome flanked by chromosomal DNA is inserted. To generate the clone from which gp120 was deleted, pNL4.3 was digested with the restriction enzymes SalI and MamI. The vector was purified by gel extraction (with β-agarase I) and subsequent phenol-chloroform extraction. A linker sequence containing the SalI and MamI restriction sites was ligated into the vector to recircularize the plasmid (Fig. 1A). Escherichia coli DH5α was transformed with this gp120 deletion clone.

FIG. 1.

(A) Construction of the pNL4.3 clone from which gp120 was deleted; (B) gp120 recombination. LTR, long terminal repeat; ds, double stranded.

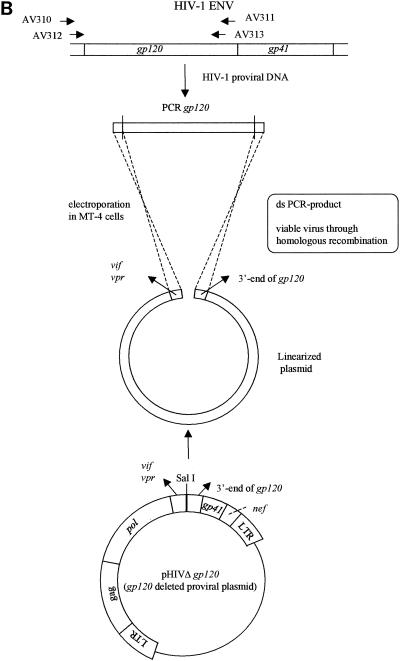

To generate the clone from which gp41 was deleted, pNL4.3 was digested with the restriction enzymes MamI and CelII. A linker sequence containing the additional XbaI restriction site was ligated into the vector to recircularize the plasmid (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

(A) Construction of the pNL4.3 clone from which gp41 was deleted; (B) gp41 recombination. LTR, long terminal repeat; ds, double stranded.

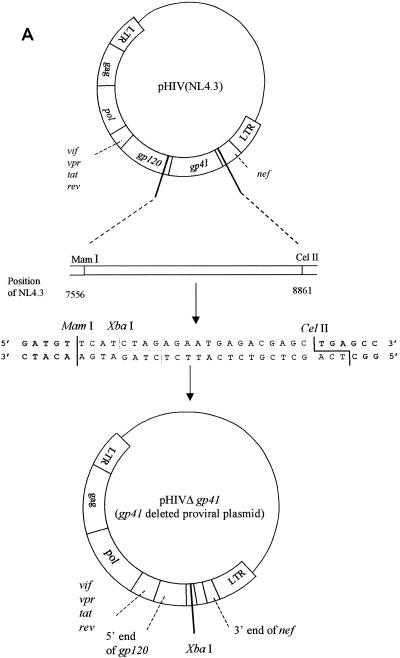

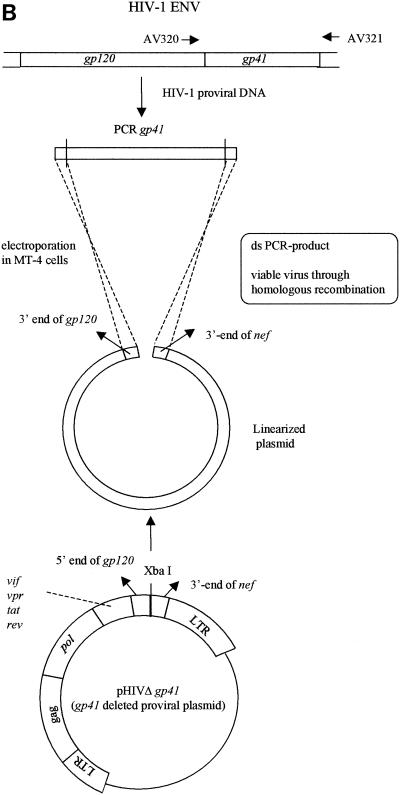

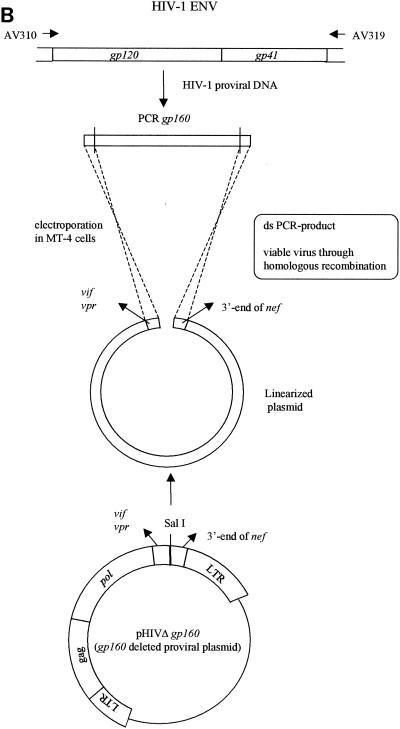

For construction of the clone from which gp160 was deleted, pNL4.3 was digested with the restriction enzymes SalI and CelII. A linker sequence containing the SalI and CelII restriction sites was ligated into the vector to recircularize the plasmid (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

(A) Construction of the pNL4.3 clone from which gp160 was deleted; (B) gp160 recombination. LTR, long terminal repeat; ds, double stranded.

Env recombination assay.

Large-scale plasmid DNA preparations of clones from which gp120, gp41, or gp160 was deleted were linearized by SalI, XbaI, or SalI digestion, respectively (Fig. 1B, 2B, and 3B, respectively). The env (gp120, gp41, or gp160) recombination assay was performed by cotransfecting the concentrated PCR product derived from the HIV strains under investigation (with different primer sets, i.e., AV312-AV313, AV320-AV321, and AV310-AV319, respectively) and linearized clone NL4.3 from which gp120, gp41, or gp160 was deleted, respectively, as described in Materials and Methods. gp120 recombinations were performed starting from HIV-1 NL4.3WT, NL4.3/AMD3100, and NL4.3/T20, resulting in R120/NL4.3WT, R120/AMD3100, and R120/T20, respectively. Gp41 and gp160 recombinations were again done with HIV-1 NL4.3WT and the NL4.3/AMD3100 and NL4.3/T20 strains selected in vitro. The resulting strains were strains R41/NL4.3, R41/AMD3100, and R41/T20, respectively, and strains R160/NL4.3, R160/AMD3100, R160/T20, respectively.

Genotypic analysis of env genes of drug-resistant and recombinant strains.

DNA sequencing analysis of the gp120-encoding regions of HIV-1 strain NL4.3 selected in the presence of AMD3100 (strain NL4.3/AMD3100) revealed several mutations that were not present in the wild-type strain (12, 13) (Table 1). The mutations Q280H and N295H and the 5-amino-acid deletion FNSTW in the V4 region have been reported to be associated with in vitro resistance to AMD3100. The mutations A299T and the 5-amino-acid deletion FNSTW were found in gp120 of the strain selected in the presence of T20 (NL4.3/T20). However, these mutations could be found in only half the virus population, as seen by population sequencing of NL4.3/T20 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Genotypic analysis and amino acid changes in gp120 gene of AMD3100-resistant isolate NL4.3/AMD3100 and T20-resistant isolate NL4.3/T20 relative to the sequence of strain NL4.3WTa

| Strain | Amino acid at the indicated amino acid position of the following region:

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V2, 147 | V3

|

V4

|

C4

|

V5, 435 | ||||||||||||

| 272 | 274 | 276 | 280 | 290 | 295 | 299 | 366 | 367 | 368 | 369 | 370 | 387 | 412 | |||

| NL4.3WTc | F | N | R | S | Q | I | N | A | F | N | S | T | W | P | Q | S |

| NL4.3/AMD3100d | L | N + S | T | R | H | V | H | T | —b | — | — | — | — | L | E | P |

| NL4.3/T20 | T | — | — | — | — | — | ||||||||||

NL4.3/AMD3100 was selected previously (12). Sequencing was done as described in Materials and Methods.

—, deletion.

C5,459, V.

C5,459, I.

The genotypic analysis of gp41 of NL4.3/T20 revealed mutations L33S and N43K (Table 2). In contrast, no mutations were found in gp41 of the strain selected in the presence of AMD3100.

TABLE 2.

Genotypic analysis and amino acid changes of gp41 gene of T20-resistant isolate NL4.3/T20 relative to sequences of NL4.3WT and pNL4a

| Strain | Amino acid at position:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 33 | 36 | 43 | |

| NL4.3 | L | G | N |

| pNL4.3 | D | ||

| NL4.3/T20 | S | K | |

Sequencing was done as described in Materials and Methods.

Sequencing analysis of a strain obtained directly after transfection of MT-4 cells with plasmid pNL4.3 revealed one genetic difference in the gp41 gene sequence in comparison to the sequence of HIV-1 NL4.3 used for the selection experiments, i.e., a negatively charged aspartic acid at position 36 of gp41 of pNL4.3 but a glycine at this position of NL4.3WT (Table 2).

After env recombination the same sequences in the respective HIV-1 NL4.3 strains selected in vitro were observed. The gp120, gp41, or gp160 recombinant HIV-1 NL4.3WT strains had the same sequence as the parental HIV-1 NL4.3 strain.

Evaluation of phenotypic resistance and cross-resistance of the strains selected.

We evaluated the antiviral activities of DS, AMD3100, AMD2763, T134, T140, T20, and AZT (as a control) against strains NL4.3/AMD3100 and NL4.3/T20. NL4.3/AMD3100 lost its susceptibility to all entry inhibitors evaluated (52- to 316-fold) except T20. NL4.3/T20 was resistant only to the compound used for selection, i.e., T20 (190-fold), whereas all other entry inhibitors remained active against this strain (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Susceptibilities of HIV-1 strains selected in vitro in the presence of AMD3100 or T20 and their gp120, gp41, and gp160 recombininant strains to virus binding and fusion inhibitors

| Virus strain | IC50 (μg/ml [fold resistancea])

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS | AMD3100 | AMD2763 | T134 | T140 | T20 | AZT | |

| NL4.3WT | 0.16 ± 0.12 | 0.01 ± 0.005 | 0.38 ± 0.29 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.008 | 0.06 ± 0.05 | 0.002 ± 0.001 |

| pNL4.3 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.01 ± 0.004 | 0.16 ± 0.07 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.008 | 0.60 ± 0.09 | 0.001 ± 0.001 |

| NL4.3/AMD3100b | 50.60 ± 22.60 (316)c | 3.02 ± 1.63 (302) | 117.5 ± 21.07 (309) | 1.57 ± 0.65 (52) | 1.28 ± 0.62 (64) | 0.08 ± 0.034 (1.4) | 0.003 ± 0.002 (1.5) |

| NL4.3/T20b | 0.35 ± 0.24 (2.2) | 0.01 ± 0.005 (1.0) | 0.43 ± 0.03 (1.1) | 0.04 ± 0.01 (1.3) | 0.01 ± 0.001 (0.5) | 11.37 ± 1.65 (190) | 0.003 ± 0.001 (1.5) |

| R120/NL4.3WTd | 0.43 ± 0.13 | 0.01 ± 0.005 | 0.25 ± 0.10 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.004 | 0.32 ± 0.21 | 0.002 ± 0.001 |

| R120/AMD3100e | 62.54 ± 36.77 (145) | 0.97 ± 0.43 (97) | 115.00 ± 24.50 (460) | 1.27 ± 0.47 (64) | 0.38 ± 0.06 (38) | 0.52 ± 0.28 (1.6) | 0.004 ± 0.002 (2.0) |

| R120/T20e | 0.71 ± 0.22 (1.7) | 0.02 ± 0.004 (2.0) | 0.34 ± 0.09 (1.4) | 0.04 ± 0.02 (2.0) | 0.02 ± 0.01 (2.0) | 0.57 ± 0.31 (1.8) | 0.003 ± 0.001 (1.5) |

| R41/NL4.3WTf | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | 0.26 ± 0.09 | 0.01 ± 0.003 | 0.01 ± 0.001 | 0.02 ± 0.004 | 0.003 ± 0.001 |

| R41/AMD3100g | 0.07 ± 0.04 (2.3) | 0.006 ± 0.005 (2.0) | 0.35 ± 0.14 (1.4) | 0.02 ± 0.01 (2.0) | 0.01 ± 0.002 (1.0) | 0.01 ± 0.005 (0.5) | 0.001 ± 0.0005 (0.3) |

| R41/T20g | 0.04 ± 0.02 (1.3) | 0.005 ± 0.003 (1.7) | 0.34 ± 0.04 (1.4) | 0.02 ± 0.01 (2.0) | 0.01 ± 0.002 (1.0) | 5.66 ± 2.79 (283) | 0.001 ± 0.0005 (0.3) |

| R160/NL4.3WTh | 0.29 ± 0.16 | 0.01 ± 0.005 | 0.48 ± 0.07 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.002 | 0.004 ± 0.003 |

| R160/AMD3100i | 54.52 ± 13.78 (188) | 1.24 ± 0.24 (124) | 71.60 ± 36.46 (149) | 1.39 ± 1.27 (28) | 0.60 ± 0.30 (30) | 0.03 ± 0.01 (1.5) | 0.003 ± 0.002 (0.8) |

| R160/T20i | 0.19 ± 0.05 (0.7) | 0.02 ± 0.005 (2.0) | 0.32 ± 0.11 (0.7) | 0.03 ± 0.01 (0.6) | 0.02 ± 0.001 (1.0) | 4.82 ± 0.34 (241) | 0.005 ± 0.002 (1.3) |

Fold increase in IC50 for HIV-1 NL4.3 and gp120, gp41, and gp160 recombinant resistant strains selected in vitro compared to the IC50 for HIV-1 NL4.3WT and the gp120, gp41, and gp160 recombinant HIV-1 NL4.3WT strains, respectively.

Strain HIV-1 NL4.3 selected in vitro in the presence of an HIV entry inhibitor (AMD3100 or T20).

Values indicating resistance are boldfaced.

HIV-1 NL4.3WT recombined with the gp120 gene of HIV-1 NL4.3WT.

HIV-1 NL4.3WT strain recombined with the gp120 gene of the strain selected in vitro in the presence of an HIV entry inhibitor (AMD3100 or T20).

HIV-1 NL4.3WT recombined with the gp41 gene of HIV-1 NL4.3WT.

HIV-1 NL4.3WT recombined with the gp41 gene of the strain selected in vitro in the presence of an HIV entry inhibitor (AMD3100 or T20).

HIV-1 NL4.3WT recombined with the gp160 gene of HIV-1 NL4.3WT.

HIV-1 NL4.3WT recombined with the gp160 gene of the strain selected in vitro in the presence of an HIV entry inhibitor (AMD3100 or T20).

Evaluation of resistance and cross-resistance of the different env recombinant viruses. (i) Evaluation of resistance and cross-resistance of gp120 recombinant strains.

The susceptibility of gp120 recombinant strain NL4.3/AMD3100 (R120/AMD3100) to all compounds evaluated matched the susceptibility of the strain originally selected in vitro (Table 3), whereas gp120 recombinant strain NL4.3/T20 (R120/T20) displayed wild-type susceptibility to all entry inhibitors tested. The wild-type gp120 recombinant strain, as well as gp120 recombinant strains NL4.3/AMD3100 and NL4.3/T20, had levels of susceptibility to the inhibitory effects of T20 5 to 10 times lower than that of original strain NL4.3. Indeed, the strain obtained directly after transfection of MT-4 cells with plasmid pNL4.3 had a level of a susceptibility to T20 10 times lower than that of strain NL4.3, which is adapted to replication in cell culture and which was used for the selection experiments (IC50s, 0.60 and 0.06 μg/ml, respectively) (Table 3).

(ii) Evaluation of resistance and cross-resistance of gp41 recombinant strains.

gp41 recombinant strain NL4.3/AMD3100 (R41/AMD3100) displayed the same susceptibility to all compounds tested as gp41 recombinant strain NL4.3 (R41/NL4.3WT). In contrast, the susceptibility of gp41 recombinant strain NL4.3/T20 (R41/T20) matched that of the strain originally selected in vitro, i.e., a 283-fold reduced susceptibility to T20 (Table 3).

(iii) Evaluation of resistance and cross-resistance of gp160 recombinant strains.

Recombination of the gp160 genes of strains NL4.3/AMD3100 and NL4.3/T20 fully reproduced the resistance phenotypes of both strains originally selected in vitro (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Since inhibitors of viral entry, i.e., the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 and the fusion inhibitor T20, were already the subjects of clinical phase II and III studies, the design of phenotypic drug resistance assays that can measure the susceptibilities of virus isolates to these new compounds is necessary. In order to analyze the development of resistance in HIV isolates in the presence of AMD3100 or T20, drug-resistant HIV-1 NL4.3 strains were selected in vitro in the presence of increasing concentrations of AMD3100 (strain NL4.3/AMD3100) (12, 13) or T20 (strain NL4.3/T20). NL4.3/AMD3100 showed phenotypic resistance to the polyanionic compound DS and the CXCR4 antagonists AMD3100, AMD2763, T134, and T140 but not to T20, whereas NL4.3/T20 only lost susceptibility to T20. Arakaki et al. (2) claimed that strains resistant to AMD3100 showed no cross-resistance to T134. In contrast, our data show a pattern of cross-resistance to T134 and T140 for strain NL4.3/AMD3100.

The selection of AMD3100 resistance elicits extensive mutations in the V3 loop, known to be important for the interaction with the CXCR4 coreceptor (31), a logical strategy by which the virus can escape the inhibitory effects of compounds (such as AMD3100) targeting the virus-CXCR4 interaction. The positively charged molecule AMD3100 selects for the mutation N295H (positively charged). In contrast, the negatively charged molecule DS selects for an aspartic acid (negatively charged) at this position (15). The A299T mutation and the FNSTW deletion, present in gp120 of NL4.3/AMD3100, are also found after selection of NL4.3 in the presence of T20. Moreover, NL4.3/T20 contains the mutations L33S and N43K in gp41. Rimsky et al. (24) reported that selection of NL4.3 in the presence of T20 resulted in the substitution I37T in gp41. Cross-resistance data for NL4.3/BRI2923, a strain previously selected in our laboratory in the presence of the dendrimer BRI2923 (32), show that T20 loses its anti-HIV activity when the mutation L33S occurs, e.g., in strains NL4.3/T20 and NL4.3/BRI2923 (V. Fikkert, C. Pannecouque, A. Hantson, B. Van Remoortel, P. Cherepanov, A. Bolmstedt, B. Matthews, G. Holan, E. De Clercq, Z. Debyser, and M. Witrouw, unpublished data).

To verify whether the mutations in the env region are fully responsible for the abilities of these selected strains to replicate in the presence of high concentrations of inhibitor, we developed env recombination techniques (Fig. 1 to 3) in which the gp120-, gp41-, or gp160-coding sequences of the selected strains can be recombined into the genetic background of a proviral clone from which the corresponding gene has been deleted. Previous studies described domain exchange in order to evaluate envelope determinants (7, 10, 11, 15). However, the recombination techniques reported here have been developed to be used in a functional semiautomated assay. These env recombination techniques allow us to delineate the region responsible for the phenotypic resistance of these selected HIV isolates to entry inhibitors. env-based CVT has now been applied to virus strains selected in the presence of AMD3100 and T20. The env sequences observed after env recombination were identical to those of the respective wild-type strain or HIV-1 strain NL4.3 selected in vitro. The susceptibilities of the NL4.3/AMD3100 gp120 recombinant strain (R120/AMD3100) and the NL4.3/T20 gp41 recombinant strain (R41/T20) to all compounds evaluated matched the susceptibilities of the strains originally selected in vitro. Evidently, recombination of the gp160 genes of NL4.3/AMD3100 and NL4.3/T20 fully reproduced the resistance phenotypes of both of the original strains selected in vitro. By relating the phenotypic susceptibility data for the strains selected in vitro and their corresponding env recombinant strains to the genotypic data, the following conclusions may be drawn. Recombination of gp120 of NL4.3/AMD3100 in a wild-type NL4.3 background fully recovered the phenotypic resistance of this strain to the entry inhibitors DS, AMD3100, AMD2763, T134, and T140, while the gp41 recombinant (R41/AMD3100) remained susceptible to all compounds. Therefore, (cross-)resistance to the entry inhibitors DS, AMD3100, AMD2763, T134, and T140 fully resides in the gp120 gene of the strain selected for its resistance to AMD3100, while the gp41 gene of this virus had no impact on resistance to entry inhibitors, as would be expected from its wild-type gp41 genotype. Similarly, recombination of the gp41 gene of NL4.3/T20 in a wild-type NL4.3 background reproduced the phenotypic resistance of this strain to T20, the only drug to which the original strain selected was resistant, whereas gp120 recombination resulted in a completely wild-type phenotype. Thus, the resistance of NL4.3/T20 is entirely due to the gp41 gene, and the gp120 mutations alone are not responsible for the observed phenotypic resistance. Since T20 inhibits HIV-1 replication following coreceptor interaction, both X4 and R5 strains are expected to be inhibited to similar extents by the compound. However, studies on the sensitivities of different HIV-1 isolates to T20 indicate that the coreceptor specificity defined by the V3 loop of gp120 modulates susceptibility to T20. R5 isolates are found to be significantly less sensitive to inhibition by T20 than X4 isolates (10, 11). In addition, Xu et al. (33) stated that a larger amount of T20 was required for the inhibition of R5 virus infection than for the inhibition of X4 virus infection. However, since the CXCR4-using laboratory strain HIV-1 NL4.3 in our selection experiments is highly adapted to the MT-4 cell line, selection of CCR5-using strains was impossible in our experimental setting.

Recombination of the gp160 gene of NL4.3/AMD3100 or NL4.3/T20 fully reproduced the resistance phenotype of the corresponding strains selected in vitro, showing that no regions outside gp160 are affected by the selection for resistance.

The wild-type gp120 recombinant strain, as well as gp120 recombinants NL4.3/AMD3100 and NL4.3/T20, showed lower levels of susceptibility to the inhibitory effect of T20 in comparison to that of the original strain, NL4.3WT. This reduced susceptibility can be explained by the genetic background of the clone from which gp120 was deleted, more precisely, the gp41 gene of plasmid pNL4.3. Indeed, the strain obtained directly after transfection of MT-4 cells with pNL4.3 was 10 times less susceptible to T20 than strain NL4.3WT, which is adapted to replication in cell culture and which was used for the selection experiments. Sequencing analysis revealed one genetic difference in env, i.e., the negatively charged aspartic acid at position 36 of gp41 in pNL4.3 in comparison to a glycine at this position in NL4.3WT. Rimsky et al. (24) claimed that this substitution (G36D) did not render NL4.3 resistant to T20. Nevertheless, the investigators claimed that the GIV-containing heptad region (sequence at positions 36 to 38 of gp41) is especially important for the binding of T20, since site-directed mutagenesis revealed that the SIM and DIM sequences at these positions of gp41 are associated with resistance to T20.

As the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 was introduced into phase II clinical trials and the fusion inhibitor T20 has proceeded to phase III trials, our data support the use of these recombination assays for phenotypic evaluation of clinical isolates that may have developed resistance mutations at the level of the envelope glycoproteins. Since the resistance of NL4.3/AMD3100 to AMD3100 and the resistance of NL4.3/T20 to T20 could be fully reproduced by gp120 and gp41 recombination assays, respectively, and by gp160 recombination assays, we conclude that env recombination can be used as a diagnostic tool to assess the susceptibility profiles of clinical strains isolated during AMD3100 or T20 treatment. When applied to clinical isolates, recombination of gp160 would be more correct than that of gp120 or gp41 alone, since recombination of the last two sequences will partly result in env sequences derived from the molecular clone. Due to the high degree of variability of the env gene, recombination of env sequences derived from clinical samples is not evident. Still, the proof of principle that the gp120- and gp160-based CVT described here is feasible for application to clinical isolates was obtained. We have successfully recombined the env sequences of one syncytium-inducing X4 strain and one syncytium-inducing X4-R5 strain into a pNL4.3 background (data not shown). Moreover, since the resistance of clinical isolates to entry inhibitors may be reflected by a shift in coreceptor usage (14), the use of cells expressing the necessary coreceptors is also required for the application of env CVT to patient samples. A CD4-positive T-cell line that is characterized by the expression of both CXCR4 and CCR5 and that is either sensitive to the CPE of HIV or transfected with a reporter gene linked to the HIV long terminal repeat should be used for this purpose. Detection of the inhibitory effects of compounds interfering with HIV entry can subsequently be determined by microscopic evaluation of a CPE or by detection of reporter gene expression.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated for the first time the design and the application of gp120, gp41, and gp160 recombination assays (env CVT). We used env-based CVT as a research tool to study the genes responsible for the observed resistance profiles of strains selected in vitro in the presence of AMD3100 or T20. Since the resistance of NL4.3/AMD3100 and NL4.3/T20 can be completely reproduced by gp120 and gp41 recombination assays, respectively, and by gp160 recombination assays, env CVT may be a powerful diagnostic tool for assessment of the susceptibilities of clinical isolates to AMD3100, T20, and other compounds that are targeted to or that interact with the viral envelope glycoproteins. Moreover, our data indicate that the strain displaying resistance to AMD3100 is still sensitive to T20 and vice versa. This is an argument in favor of pursuing combinations of several classes of inhibitors interfering with different steps in the HIV entry process for clinical use in future anti-HIV therapeutic drug regimens.

Acknowledgments

These investigations were supported by the Belgian Geconcerteerde Onderzoeksacties (GOA 00/12, Vlaamse Gemeenschap).

We are grateful to Kristien Erven and Liesbet De Dier for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi, A. H., E. Gendelman, S. Koenig, R. Willey, A. Rabson, and M. A. Martin. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 59:284-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arakaki, R., H. Tamamura, M. Premanathan, K. Kanbara, S. Ramanan, K. Mochizuki, M. Baba, N. Fujii, and H. Nakashima. 1999. T134, a small molecule CXCR4 inhibitor, has no cross-drug resistance with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist with a different structure. J. Virol. 73:1719-1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baba, M., R. Pauwels, J. Balzarini, J. Arnout, J. Desmyter, and E. De Clercq. 1988. Mechanism of inhibitory effect of dextran sulfate and heparin on replication of human immunodeficiency virus in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:6132-6136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baba, M., O. Nishimura, N. Kanzaki, M. Okamoto, H. Sawada, Y. Iizawa, M. Shiraishi, Y. Aramaki, K. Okonogi, Y. Ogawa, K. Meguro, and M. Fujino. 1999. A small-molecule nonpeptide CCR5 antagonist with highly potent and selective anti-HIV-1 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:5698-5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridger, G. J., R. T. Skerlj, S. Padmanabhan, S. A. Martellucci, G. W. Henson, M. J. Abrams, N. Yamamoto, K. De Vreese, and R. Pauwels. 1995. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship of phenylenebis(methylene)-linked bis-tetraazamacrocycles that inhibit HIV replication. Effect of heteroaromatic linkers on the activity of bicyclams. J. Med. Chem. 38:366-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan, D. C., and P. S. Kim. 1998. HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell 93:681-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cocchi, F., A. L. DeVico, A. Garzino-Demo, A. Cara, R. C. Gallo, and P. Lusso. 1996. The V3 domain of the HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein is critical for chemokine-mediated blockade of infection. Nat. Med. 2:1244-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Clercq, E., N. Yamamoto, R. Pauwels, M. Baba, D. Schols, H. Nakashima, J. Balzarini, Z. Debyser, B. A. Murrer, D. Schwartz, D. Thornton, G. Bridger, S. Fricker, G. Henson, M. Abrams, and D. Picker. 1992. Potent and selective inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 and HIV-2 replication by a class of bicyclams interacting with a viral uncoating event. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:5286-5290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Clercq, E., N. Yamamoto, R. Pauwels, J. Balzarini, M. Witvrouw, K. De Vreese, Z. Debyser, B. Rosenwirth, P. Peichl, R. Datema, D. Thornton, R. Skerlj, F. Gaul, S. Padmanabhan, G. Bridger, G. Henson, and M. Abrams. 1994. Highly potent and selective inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus by the bicyclam derivative JM3100. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:668-674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derdeyn, C. A., J. M. Decker, J. N. Sfakianos, X. Wu, W. A. O'Brien, L. Ratner, J. C. Kappes, G. M. Shaw, and E. Hunter. 2000. Sensitivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to the fusion inhibitor T-20 is modulated by coreceptor specificity defined by the V3 loop of gp120. J. Virol. 74:8358-8367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derdeyn, C. A., J. M. Decker, J. N. Sfakianos, Z. Zhang, W. A. O'Brien, L. Ratner, G. M. Shaw, and E. Hunter. 2001. Sensitivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to fusion inhibitors targeted to the gp41 first heptad repeat involves distinct regions of gp41 and is consistently modulated by gp120 interactions with the coreceptor. J. Virol. 75:8605-8614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Vreese, K., V. Kofler-Mongold, C. Leutgeb, V. Weber, K. Vermeire, S. Schacht, J. Anne, E. De Clercq, R. Datema, and G. Werner. 1996. The molecular target of bicyclams, potent inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus replication. J. Virol. 70:689-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Vreese, K., D. Reymen, P. Griffin, A. Steinkasserer, G. Werner, G. J. Bridger, J. Este, W. James, G. W. Henson, J. Desmyter, J. Anne, and E. De Clercq. 1996. The bicyclams, a new class of potent human immunodeficiency virus inhibitors, block viral entry after binding. Antivir. Res. 29:209-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esté, J. A., C. Cabrera, J. Blanco, A. Guttierrez, G. Bridger, G. Henson, B. Clotet, D. Schols, and E. De Clercq. 1999. Shift of clinical human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from X4 to R5 and prevention of emergence of the syncytium-inducing phenotype by blockade of CXCR4. J. Virol. 73:5577-5585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esté, J. A., D. Schols, K. De Vreese, K. Van Laethem, A. M. Vandamme, J. Desmyter, and E. De Clercq. 1997. Development of resistance of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to dextran sulfate associated with the emergence of specific mutations in the envelope gp120 glycoprotein. Mol. Pharmacol. 52:98-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hertogs, K., M.-P. de Béthune, V. Miller, T. Ivens, P. Schel, A. Van Cauwenberge, C. Van Den Eynde, V. Van Gerven, H. Azijn, M. Van Houtte, F. Peeters, S. Staszewski, M. Conant, S. Bloor, S. Kemp, B. Larder, and R. Pauwels. 1998. A rapid method for simultaneous detection of phenotypic resistance to inhibitors of protease and reverse transcriptase in recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from patients treated with antiviral drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:269-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horwitz, J. P., J. Chua, and M. Noel. 1964. Nucleoside V. The monomesylates of 1-(2′-deoxy-β-d-lyxofuranosyl) thymine. J. Org. Chem. 29:2076-2078. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kellam, P., and B. A. Larder. 1994. Recombinant virus assay: a rapid phenotypic assay for assessment of drug susceptibility of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:23-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larder, B., D. Richman, and S. Vella. 1998. HIV resistance and implications for therapy. Medicom Inc., Atlanta, Ga.

- 20.Maschera, B., E. Furfine, and E. D. Blair. 1995. Analysis of resistance to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors by using matched bacterial expression and proviral infection vectors. J. Virol. 69:5431-5436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyoshi, I., H. Taguchi, I. Kobonishi, S. Yoshimoto, Y. Ohtsuki, and Y. Shiraishi. 1982. Type C virus-producing cell lines derived from adult T cell leukemia. Gann Monogr. 28:219-228. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murakami, T., T. Nakajima, Y. Koyanagi, K. Tachibana, N. Fujii, H. Tamamura, N. Yoshida, M. Waki, A. Matsumoto, O. Yoshie, T. Kishimoto, N. Yamamoto, and T. Nagasawa. 1997. A small molecule CXCR4 inhibitor that blocks T cell line-tropic HIV-1 infection. J. Exp. Med. 186:1389-1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pauwels, R., J. Balzarini, M. Baba, R. Snoeck, D. Schols, P. Herdewijn, J. Desmyter, and E. De Clercq. 1988. Rapid and automated tetrazolium-based colorimetric assay for the detection of anti-HIV compounds. J. Virol. Methods 20:309-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rimsky, L. T., D. C. Shugars, and T. J. Matthews. 1998. Determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to gp41-derived inhibitory peptides. J. Virol. 72:986-993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schols, D., S. Struyf, J. Van Damme, J. A. Esté, G. Henson, and E. De Clercq. 1997. Inhibition of T-tropic HIV strains by selective antagonization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J. Exp. Med. 186:1383-1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamamura, H., A. Arakaki, H. Funakoshi, M. Imai, A. Otaka, T. Ibuka, H. Nakashima, T. Murakami, M. Waki, A. Matsumoto, N. Yamamoto, and N. Fujii. 1998. Effective lowly cytotoxic analogs of an HIV-cell fusion inhibitor, T22 (Tyr5,12, Lys7-polyphemusin II). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 6:231-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamamura, H., Y. Xu, T. Hattori, X. Zhang, R. Arakaki, K. Kanbara, A. Omagari, A. Otaka, T. Ibuka, N. Yamamoto, H. Nakashima, and N. Fujii. 1998. A low-molecular-weight inhibitor against the chemokine receptor CXCR4: a strong anti-HIV peptide T140. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 253:877-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vandamme, A.-M., K. Van Laethem, and E. De Clercq. 1999. Managing resistance to anti-HIV drugs. An important consideration for effective disease management. Drugs 57:337-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vandamme, A.-M., M. Witvrouw, C. Pannecouque, J. Balzarini, K. Van Laethem. J. C. Schmidt, J. Desmyter, and E. De Clercq. 1999. Evaluating clinical isolates for their phenotypic and genotypic resistance against anti-HIV drugs, p. 223-258. In D. Kinchington and R. F. Schinazi (ed.), Methods in molecular medicine: antiviral methods and protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, N.J. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Vartanian, J. P. 2000. AMD3100 AnorMED. Idrugs 3:811-816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verrier, F., A. M. Borman, D. Brand, and M. Girard. 1999. Role of the HIV type 1 glycoprotein 120 V3 loop in determining coreceptor usage. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 15:731-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witvrouw, M., V. Fikkert, W. Pluymers, B. Matthews, K. Mardel, D. Schols, J. Raff, Z. Debyser, E. De Clercq, G. Holan, and C. Pannecouque. 2000. Polyanionic (i.e. polysulfonate) dendrimers can inhibit the replication of human immunodeficiency virus by interfering with both virus adsorption and later steps (reverse transcriptase/integrase) in the virus replicative cycle. Mol. Pharmacol. 58:1100-1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu, Y., X. Zhang, M. Matsuoka, and T. Hattori. 2000. The possible involvement of CXCR4 in the inhibition of HIV-1 infection mediated by DP178/gp41. FEBS Lett. 487:185-188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]