Abstract

The dramatic increase over the past 10 years in the amount of available clinical research on the use of antidepressants to treat major depression in children and adolescents has substantially improved our knowledge of the safety and efficacy of these medications in the pediatric population. Many questions remain, however, that highlight the need to continue research in this patient population rather than relying on the extrapolation of data from trials involving adults. In this article, we review the current state of research into antidepressant therapy for major depression in children and adolescents. In addition, we discuss methodologic issues and clinical implications specific to the pediatric population.

Major depressive disorder affects up to 10% of youths and is associated with substantial short-and long-term morbidity and mortality.1,2 Depression is associated with functional impairment in school and at work and can be associated with problems.3–6 Symptoms of depression in youths are similar to those experienced by adults. However, some children and adolescents with depression do not have actual “depressed mood” (feeling down or blue) and instead may experience increased irritability, which may occur with or without depressed mood. Depression in the pediatric population presents in various ways. A common presentation is a teenager who has had a sudden drop in grades, experiences frequent irritability, has a change in friends, participates in fewer social or recreational activities, has recently changed eating or sleeping patterns, has frequent fatigue and experiences feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness or suicidal thinking. In addition, many adolescents with depression are at increased risk of substance abuse and attempted and completed suicide.5,7

In 90% of cases, young people recover from the depressive episode within 1 to 2 years, some even without treatment.4,8 However, episodes can recur in 40%–70% of cases.9 In the long-term, adolescents with depression are more likely than those without it to have an episode of depression or other mental health issues in adulthood.10,11

Antidepressants prescribed to adults are used to treat depression in children and adolescents. Because of the lack of benefit of tricyclic antidepressants in pediatric cases, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin– norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have been increasingly used in this patient population.12 Before 1997, there were no published reports of any antidepressant being better than placebo for the treatment of depression in childhood. Research into the efficacy and safety of these drugs has expanded dramatically over the last 10 years, in part as a result of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Modernization Act of 1997, which provided an incentive (6-month patent extension) to provide pediatric data on new and existing medications. Before 1995, only 250 children and adolescents with depression had been included in double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCTs). This number has now increased to over 2800.

This increase in available evidence triggered the recent controversy about the safety and the efficacy of antidepressants, in particular SSRIs (fluoxetine, citalopram, escitalopram, paroxetine and sertraline) and SNRIs (mirtazapine, nefazodone and venlafaxine). Following many months of reviewing the safety data, regulatory agencies in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada have issued warnings about the increased risk of suicidal behaviour in children and adolescents using these medications. Yet, untreated depression is also problematic. In the recent Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS), conducted at 13 centres in the United States, specific psychotherapy (cognitive behavioural therapy) was not found to be more effective than placebo.13 Furthermore, specific psychotherapies are simply not readily available in most communities. Therefore, drug therapy may continue to play an important role in the treatment of major depression in children and adolescents.

Understanding the efficacy and safety profiles of antidepressants is therefore important. Yet, for clinicians, interpreting the data is often difficult given the competing opinions on both efficacy and safety. In this article, we will review the evidence from published and unpublished RCTs on the efficacy of antidepressants in treating major depressive disorder in children and adolescents and on the emergence of suicidality (suicidal thinking and behaviour) associated with antidepressants. In addition, we will discuss the methodologic differences between the RCTs reviewed and how these differences may have contributed to the variation in outcomes reported. This discussion should make it easier for clinicians to evaluate the available data.

Methods

We obtained data for review from published RCT reports in peer-reviewed journals and meeting abstracts and from unpublished RCTs in the public domain (available from the Web sites of the FDA, the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency [MHRA] and GlaxoSmithKline). Clinical trials in this review included large RCTs of antidepressants involving subjects less than 18 years old with depression that were identified through the extensive safety review conducted by the FDA in 2004. The FDA reviewed 6 published reports (3 of fluoxetine13–15 and 1 each of paroxetine,16 sertraline17 and citalopram18) and 10 unpublished studies (2 each of paroxetine,19,20 venlafaxine,21 nefazodone22 and mirtazapine [unpublished data on file with Organon Inc.], and 1 each of citalopram23,24 and escitalopram25).

Efficacy

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Table 1 provides the primary outcomes and response rates (CGI-I scores) reported in each of the 16 SSRI and SNRI trials. The results of the SSRI trials were mixed except for those of the 3 fluoxetine trials.13–15 All of the fluoxetine trials demonstrated a significant improvement among subjects prescribed the drug than among those given placebo. Fluoxetine is the only drug approved for the treatment of depression in children and adolescents. The response rates were about 30%– 40% in the placebo groups and 50%–60% in the fluoxetine-only groups. The most recent study (TADS) compared fluoxetine alone, cognitive behavioural therapy alone, fluoxetine plus cognitive behavioural therapy, and placebo alone in 439 subjects aged 12–17 years over 12 weeks.13 In this study, 61% of those receiving fluoxetine alone had CGI-I scores that indicated a response, as compared with only 35% of those given placebo (p = 0.001). Combination treatment with fluoxetine plus cognitive behavioural therapy was even more effective (71% of patients responded). However, the proportion of patients in the psychotherapy-only group who responded (43%) was not significantly higher than the proportion in the placebo group. Despite widespread scrutiny of the outcomes of many of the antidepressant trials, the results of all 3 of the fluoxetine trials were considered positive by the MHRA and the FDA.

Table 1

The other SSRI trials reported mixed results. In the published trial of paroxetine,16 many of the secondary outcomes, including CGI-I scores, were positive, but no significant difference between patient groups was found in the primary outcome. In this study, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD), an adult rating scale, was used as the primary outcome measure. The findings led researchers to determine that adult measures are not appropriate for pediatric populations. This study was the only RCT to use another drug (imipramine) as a comparator. Imipramine was not found to be significantly better than placebo in any of the outcomes.16 The other 2 paroxetine trials showed no benefit for the drug in all of the outcomes.19,20

Two identical studies were conducted in 53 centres in the United States, India, Canada, Costa Rica and Mexico to compare sertraline and placebo for 10 weeks.17 Based on the primary outcome measure (change from baseline in CDRS-R score), patients given sertraline had significantly greater improvement than those given placebo (change in score –22.8 v. –20.2; p = 0.007). Also, more patients in the treatment group than in the placebo group were considered responders (69% v. 59%, respectively, achieved at least 40% decrease in CDRS-R score, p = 0.05; and 63% v. 53%, respectively, had a CGI-I score indicating “very much” or “much” improved, p = 0.05). Neither of the individual studies was positive for sertraline; however, the drug–placebo difference did reach significance for the combined data. Although the trials were not powered to detect differences by age group, there was some suggestion that sertraline may have been more effective among the adolescents than among the children in the study.

There were 2 placebo-controlled studies of citalopram. In the one that was published,18 patients receiving the drug had a significantly greater improvement in CDRS-R scores than those in the placebo group; the effect was noted as early as week 1 (p < 0.05) and continued throughout the study. The difference in response rates between the citalopram and placebo groups (36% v. 24%, respectively, had a CDRS-R score £ 28) was also significant (p < 0.05). Many studies use a CDRS-R score of 28 or less as a response criterion; thus, the low response rates in this study are consistent with the remission rates reported in other studies. Despite a positive effect of citalopram demonstrated by the continuous measure, the CGI did not show differences between the treatment and placebo groups (47% and 45%, respectively, had CGI scores that indicated a response); however, this may have been because the CDRS-R and CGI were completed by different raters.

The second citalopram study showed no evidence of efficacy.23,24 However, it included inpatients as well as outpatients, which may suggest an increased level of depression severity. In addition, there was a high attrition rate in both groups (citalopram 40% and placebo 34%), which makes it difficult to interpret the results.

A recent placebo-controlled trial of escitalopram25 showed no difference between the treatment group and the placebo group in the primary outcome measure of CGI-I scores. However, among the adolescents who completed the trial, those in the escitalopram group had a significantly greater improvement in CDRS-R scores at the end point than those in the placebo group (p = 0.047).

In summary, there appears to be some evidence of efficacy for paroxetine, sertraline and citalopram, but fluoxetine was found to be efficacious in more than 1 RCT.

Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

Two RCTs were conducted of each of the SNRIs nefazodone, venlafaxine and mirtazapine for the treatment of pediatric depression. One of the nefazodone trials demonstrated efficacy on some of the outcome measures but not on the primary outcome measure (change in CDRS-R score).22 The other nefazodone trial did not report evidence of efficacy.22 Both of the venlafaxine trials21 and the mirtazapine trials (unpublished data on file with Organon Inc.) reported negative results owing to high response rates in the placebo groups. When the results of the venlafaxine trials were pooled, there was some evidence of benefit among adolescents.21 However, the evidence is insufficient to support the use of non-SSRIs for the treatment of major depression in children and adolescents.

Methodologic issues regarding efficacy outcomes

The studies used a variety of outcome measures and response criteria. In general, the RCTs involved a standard assessment of symptoms by a clinician during an interview with the patient and his or her parents. Earlier studies involving adults with depression used adult rating scales. Later studies involving children and adolescents used child-specific scales (e.g., Childhood Depression Rating Scale–Revised [CDRS-R]), which integrate information from both the patient and the parents. In addition, the clinical assessment of global improvement (i.e., Clinical Global Impression–Improvement [CGI-I] scale) is commonly used, particularly to define a patient's response to treatment; a score of 1 or 2 (“very much” or “much” improved) is considered an indication of a response to medication. The CGI is the only outcome that was consistent across all of the RCTs reviewed. Unfortunately, there is no “best” method for assessing outcomes, although child-specific scales are preferable to adult rating scales.

On the basis of the interpretation of trial data by the MHRA and the FDA, 40% (4/10) of the RCTs of SSRI therapy for depression in children and adolescents reported positive findings. This rate is similar to that among trials involving adults (about 50%). Regulatory agencies such as the FDA require 2 positive trials before it will declare a medication effective. With up to 50% of adult trials failing, it frequently takes up to 4–5 studies to achieve the required 2 positive trials.26 However, it is unlikely that more than 2 studies of a single medication will ever be completed in the pediatric population, since pharmaceutical companies are required to conduct only 2 pediatric trials for a patent extension. Furthermore, the estimate of 40% is conservative and does not include the trials that showed positive results for some but not all outcome measures.16,17

There are methodologic issues that likely had an impact on the results of the 10 studies. More specific details about the methodology of these studies can be found in a review of the study designs used by the FDA Advisory Committee to evaluate the studies in September 2004 (www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/04/briefing/2004-4065b1-08-TAB06-Dubitsky-Review.pdf). We will review some of the major methodologic issues here.

To begin, the range of response rates to placebo in these trials (33%–59%) may have been due in part to methodologic differences between the trials. Many of the trials that failed to show evidence of efficacy did so because the placebo response rate was so high. Several factors may have contributed to these high response rates. It is unclear in these cases whether the trial results were negative because the medication was not effective (unlikely, since the response rate was also high in the treatment groups) or whether there were methodologic issues leading to high response rates for all of the subjects. Because the trials did not use another drug as an active comparator, it is impossible to determine the cause.

The first difference between the trials was the number of sites involved. Increasing the number of sites in a trial increases the variability in the conduct of the study, which may influence outcomes. Similarly, the number of subjects per site is relevant. With more subjects per site, investigators become more familiar with the study protocol and intervention strategies.

Another difference is the experience of the site staff and investigators in (a) assessing and treating depression in children and adolescents and (b) using rating scales for outcome measures. As suggested by Wagner and colleagues in the sertraline study,17 the possible reasons for the high placebo rate in that study included the experience of the investigators, the large number of participating sites, the low number of subjects at each site and the fact that the sites were in different countries.

Another area in which the trials differed was patient selection. Although most of the studies recruited only subjects who met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder criteria for major depressive disorder of at least moderate severity, other inclusion and exclusion criteria varied, including age, severity of illness, comorbid disorders, and ancillary pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions. For example, some of the trials recruited only adolescents, whereas others included children and adolescents. Some of the studies that reported negative findings showed evidence of efficacy among the adolescents but not among the children.17,21 The source of recruitment may also have influenced the outcome. In a study of cognitive behavioural therapy for depression in adolescents, Brent and colleagues reported higher response rates among subjects who learned of the study through advertisements than among those who were clinical referrals.27

Another factor that may have affected outcomes is study design. Duration of assessment, use of placebo run-in periods, duration of acute treatment and dosing all affect results. For example, Rintelmann and colleagues reported that an extended evaluation period (2 weeks) led to improvement in some subjects during the course of the evaluation.28 Placebo run-in periods help to prevent a placebo response. Two of the fluoxetine studies used placebo run-in periods, and the third (the TADS) used an extended evaluation period without a placebo run-in period; all 3 reported low placebo response rates.13–15

Finally, special attention must be paid to the selection of the primary outcome measure, since this is the focus of regulatory agencies. However, in reviewing the studies, a decision about whether a study's findings are positive or negative cannot always be based strictly on the primary outcome measure. Future trials should consider having standard outcome measures, which would allow for easier comparison and interpretation of results across studies.

Safety

Suicidality

Suicidal behaviour has been reported in children and adolescents prescribed antidepressants, both in case reports and in clinical trials. One difficulty in interpreting suicidal behaviour in depression studies is that suicide attempts and suicidal ideation are common symptoms of depression. If a suicide attempt is made during the course of treatment, it is difficult to identify the cause or causes of the event. It could be a lack of improvement or worsening of depressive symptoms, increased activation (increased energy either from improvement in the mood disorder or due to the medication), or it could be directly linked to the medication. The use of a placebo control group helps to answer some but not all of the questions.

The FDA conducted an independent examination of the adverse event data from all clinical trials of SSRIs and SNRIs, both for depression and for all indications. Each harm-related adverse event was evaluated and reclassified as “suicidal,” “non-suicidal” or “indeterminate.” Among the events classified as suicidal were suicide attempts, suicidal ideation and “preparatory actions toward imminent suicidal behaviour.” The events classified as non-suicidal included self-injurious behaviours without suicidal intent.

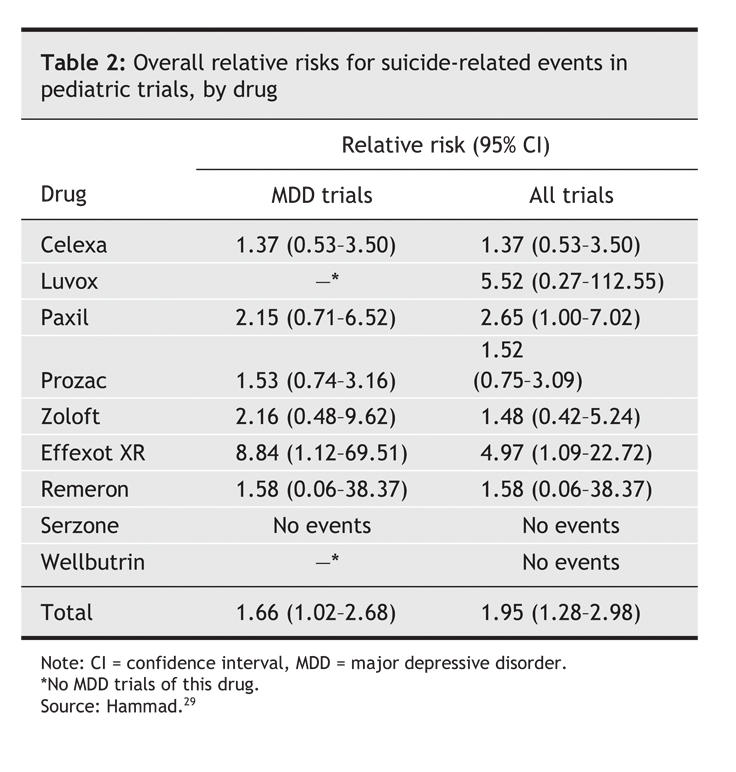

Table 2 presents the results of the FDA analysis of suicide-related events (attempts or ideation) in pediatric RCTs of antidepressant therapy for major depressive disorder and for all indications.29 Data for major depressive disorder are from the trials reported in the efficacy section of this article; data for all indications are from those same trials and from additional studies of other disorders (e.g., anxiety disorders). For all indications, the relative risk of suicide-related events was significantly increased among subjects given medication (relative risk [RR] 1.95, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.28– 2.98). The same was true in the trials of therapy for major depressive disorder (RR 1.66, 95% CI 1.02–2.68). The average risk of such events among patients receiving antidepressants was 4%, twice that among patients given placebo (2%). Because of the relative rarity of these events (97 among more than 4200 children and adolescents included in the trials), the difference was only significant when data from all of the trials were pooled. Except for venlafaxine, individual medications were not statistically more likely than other medications to lead to suicidal behaviour. No suicides occurred in these trials.

Table 2

Contrary to the results of the clinical trials, data from observational studies involving both adults and youths suggest an inverse relation between treatment with antidepressants and suicidality. During the late 1990s, the incidence of suicide among youths in the United States decreased as the number of antidepressant prescriptions increased.30 Similar associations during this period were found in other developed countries, including Sweden, Norway, Finland and Denmark.30,31

A more recent epidemiologic study showed an association between increased prescription of antidepressants and decreased incidence of completed suicides among youths in the United States after adjustment for such factors as physician availability.32 A similar study conducted in Australia involving adolescents 15 years and older reported contradictory results: the investigators noted no decrease in the incidence of suicide despite trends showing increased antidepressant use.33 However, in the same study, groups with the greatest exposure to antidepressants had a decreased incidence of suicide. Valuck and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study to examine the link between antidepressant treatment and suicide attempts among patients aged 12–18 with newly diagnosed depression.34 Subjects were enrollees in both commercial and publicly funded (Medicaid) managed care plans. The results indicated that antidepressant therapy did not increase the risk of suicide attempts and that such therapy taken for more than 180 days reduced the likelihood of suicide attempts compared with treatment taken for less than 55 days.

Studies of completed suicides showed that, among the subjects who had been prescribed antidepressants, few (less than 10%) tested positive for antidepressants at autopsy.35–37 In one of the studies,35 24% of the 49 adolescents who had committed suicide had been prescribed antidepressants; however, none tested positive for antidepressants post mortem. Leon and colleagues examined serum toxicology results in cases of suicide involving youths less than 18 years of age in New York City between 1993 and 1998.37 To capture any suicides misclassified as accident-related deaths, they also included youths whose deaths were the result of accidents during the same period. Because antidepressants may not be detected in the serum after several days, only youths whose injury-related death occurred less than 3 days before serum toxicology tests were done were included in the study (82% [58/66] of suicide-related deaths). Only 4 of the 58 youths tested positive for antidepressants (imipramine 2, fluoxetine 2). Similar results have been found in postmortem studies of completed suicides by adults.36,38

Therefore, there is emerging evidence from observational studies that contradicts the findings of the FDA's review. It is difficult to reconcile the epidemiologic data showing decreased numbers of completed suicides with the data from the clinical trials showing increased suicidal ideation and behaviour among youths prescribed antidepressants. Increases in suicidal ideation and behaviour are relatively common in depression, whereas completed suicides are far less common. It is possible that slight increases in ideation do not, in fact, result in an increase in actual completed suicides.

Methodologic issues regarding safety outcomes

The reliability of the data on suicidal behaviours in these trials was greatly improved when the suicide-related events were reviewed by the FDA. The original data, which were based on classifications by the drug manufacturers, clearly had some issues with inadequate labelling of the events. However, even the FDA review was based on site-level documentation. Although some trials had relatively elaborate descriptions of the events, others provided only minimal information. In addition, any prior suicidal behaviours of the subjects were not reported. Because suicidal behaviours are generally highly associated with suicide-related events,39 it is crucial for studies to report both the adverse event as well as the known history of similar behaviours of these subjects. From our review, only one trial collected and reported this information.14 Finally, although there was increased risk of suicidal behaviour associated with antidepressants, this risk included suicide attempt, preparatory acts and suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation accounted for the majority of the events, and there were no completed suicides among the 4400 youths included in the trials.

Interpretation

Given the methodologic differences between the trials and the range of drug and placebo response rates reported, clinicians need to be judicious in their interpretation of data from pediatric antidepressant trials. The current recommendations for antidepressant therapy in children and adolescents are being debated, and many question are being raised about the strength of the evidence supporting them. In this evolving field, outcome measures have varied widely across studies. Finding the most effective outcome measures remains a challenge. The results of most trials are not definitive (all positive or all negative). Clinicians, therefore, must evaluate the overall trial.

Evidence from SSRI trials involving adults indicates that the drugs are equally efficacious. It is unlikely that these drugs will behave any differently in youths. The rates of placebo response have differed remarkably across trials, from 33% to 59%. Does that mean that there is different efficacy among placebos? We would suggest that the differences are likely the result of methodologic issues between studies rather than a true difference between the medications.

Finally, the most controversial issue involves the rates of suicide-related events. It is important to distinguish between suicidal ideation and completed suicides, or even suicide attempts. As has been known for years, children and adolescents with depression requiring drug therapy need to be closely monitored, particularly during the early stages of treatment or after dose escalations. Clinicians need to be informed about the nature of the events reported in the clinical trials in order to adequately describe the benefits and risks of antidepressants to patients and their families. Further details regarding the FDA's review and the data presented here can be found on the FDA's Web site (www.fda.gov/cder/drug/antidepressants).

Clinical recommendations

Major depressive disorder affects up to 10% of youths. Clinicians are faced with the difficult task of treating depression in this population. Data from clinical trials have suggested a possible association between worsening or new suicidal behaviour in youths prescribed antidepressants. However, no predictive factors have been determined. Therefore, clinicians need to be vigilant about the emergence of these adverse events. Other important points for clinicians who care for children and adolescents with major depression include the following:

• A careful assessment is critical if depression is suspected in children and adolescents.

• If depression is diagnosed, patients and their families need to be educated about the illness and the options available for treatment. Advocacy agencies (e.g., the Mood Disorders Association of Ontario and the National Alliance on Mental Illness) can provide needed resources for education.

• Clinicians should determine if there has been any history of suicidal behaviours. They should ask about suicidal behaviours at all subsequent visits.

• If antidepressant therapy is required, patients and their families need to be fully informed about the risks and benefits. Drug therapy should be started at a low dose (equivalent of 5–10 mg of fluoxetine) and the dose increased every 2 weeks until the maximum dose is reached if no significant adverse events emerge.

• In particular, patients and their families need to be fully informed about the risk of suicidal behaviours with antidepressant treatment. Families should be asked to monitor patients closely for worsening depression, worsening or new suicidal ideation or behaviours, and other behavioural side effects. To aid in this process, families may wish to use tools available through such organizations as the National Alliance on Mental Illness (www.nami.org), Families for Depression Awareness (www.familyaware.org) and the Canadian Mental Health Association (www.cmha.ca/highschool/english.htm).

• The FDA suggests weekly monitoring in person for the first 4 weeks after the start of antidepressant treatment or after any subsequent dose adjustment.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All of the authors contributed to the development and writing of the manuscript and approved the final version to be published.

Competing interests: None declared for Taryn Mayes. Amy Cheung has received speaker fees from Eli Lilly and Company. Graham Emslie has received research grants from Eli Lilly, Organon Inc. and Forest Laboratories Inc.; he has been a consultant to Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Forest Laboratories, Pfizer Inc. and Wyeth-Ayerst; and is with the Speaker Bureau of McNeil-PPC, Inc.

Correspondence to: Dr. Amy H. Cheung, Health Systems Research and Consulting Unit, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 33 Russell St., 3rd Floor Tower, Toronto ON M5S 2S1; amy_cheung@camh.net

REFERENCES

- 1.Pataki CS, Carlson GA. Childhood and adolescent depression: a review. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1995;3:140-51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Fleming JE, Offord DR, Boyle MH. Prevalence of childhood and adolescent depression in the community. Ontario Child Health Study. Br J Psychiatry 1989;155:647-54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Kandel DB, Davies M. Adult sequelae of adolescent depressive symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986;43:255-62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Kovacs M, Feinberg TL, Crouse-Novak MA. Depressive disorders in childhood: I. A longitudinal prospective study of characteristics and recovery. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984;41:229-37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Rao U, Ryan ND, Birmaher B, et al. Unipolar depression in adolescents: clinical outcome in adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995;34:566-78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Are adolescents changed by an episode of major depression? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994;33:1289-98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Kovacs M, Feinberg TL, Crouse-Novak MA. Depressive disorders in childhood: II. A longitudinal study of the risk for a subsequent major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984;41:643-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.McCauley E, Myers K, Mitchell J, et al. Depression in young people: initial presentation and clinical course. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993;32:714-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, et al. Childhood and adolescent depression: a review of the past 10 years. Part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996;35:1427-39. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Harrington R, Fudge H, Rutter M, et al. Adult outcomes of childhood and adolescent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990;47:465-73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Weissman MM, Wolk S, Goldstein RB, et al. Depressed adolescents grown up. JAMA 1999;281:1707-13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Hazell P, O'Connell D, Heathcote D, et al. Tricyclic drugs for depression in children and adolescents. [Cochrane Review] In: The Cochrane Library; Issue 2, 2002. Oxford: Update Software. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al; Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) Team. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;292:807-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Emslie GJ, Heiligenstein JH, Wagner KD, et al. Fluoxetine for acute treatment of depression in children and adolescents: a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;41:1205-15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Emslie GJ, Rush AJ, Weinberg WA, et al. Double-blind placebo controlled study of fluoxetine in depressed children and adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997;54:1031-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Keller MB, Ryan ND, Strober M, et al. Efficacy of paroxetine in the treatment of adolescent major depression: A randomized, controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40:762-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Wagner KD, Ambrosini PJ, Rynn M, et al. Efficacy of sertraline in the treatment of children and adolescents with major depressive disorder: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2003;290:1033-41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Wagner KD, Robb AS, Findling RL, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of citalopram for the treatment of major depression in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1079-83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.A double-blind, multicentre placebo controlled study of paroxetine in adolescents with unipolar major depression [trial 377]. Available on the GlaxoSmithKline Web site: www.gsk.com/media/paroxetine.htm (accessed 2005 Dec 6).

- 20.A randomized, multicenter, 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled flexible-dose study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of paroxetine in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder [trial 701]. Available on the GlaxoSmithKline Web site: www.gsk.com/media/paroxetine.htm (accessed 2005 Dec 6).

- 21.Emslie GJ, Findling RL, Yeung PP, et al. Efficacy and safety of venlafaxine ER in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. Presented at the American Psychiatric Association Conference; 2004 May 1-6; New York.

- 22.Emslie GJ, Findling RL, Rynn MA, et al. Efficacy and safety of nefazodone in the treatment of adolescents with major depressive disorder [abstract]. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2002;12:299.

- 23.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Antidepressant use in children, adolescents, and adults. Rockville (MD): US Food and Drug Administration. Available: www.fda.gov/cder/drug/antidepressants (created 2004 Mar 22; updated 2005 July 12; accessed 2005 Dec 9).

- 24.Cheung AH, Emslie GJ, Mayes TL. Review of the efficacy and safety of antidepressants in youth depression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2005;46(7):735-54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Wagner KD, Jonas J, Bose A, et al. Controlled trial of escitalopram in the treatment of pediatric depression. Presented at the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry annual meeting; Oct 2004; Washington. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Khan A. Khan SR. Walens G. Kolts R. Giller EL. Frequency of positive studies among fixed and flexible dose antidepressant clinical trials: an analysis of the food and drug administration summary basis of approval reports. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003;28:552-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Brent DA, Kolko DJ, Birmaher B, et al. Predictors of treatment efficacy in a clinical trial of three psychosocial treatments for adolescent depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998;37:906-14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Rintelmann JW, Emslie GJ, Rush AJ, et al. The effects of extended evaluation on depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. J Affect Disord 1996;41:149-56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Hammad TA. Results of the analysis of suicidality in pediatric trials of newer antidepressants. Presented to the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee and the Pediatric Advisory Committee, US Food and Drug Administration; September 13-14, 2004. Available: www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/04/slides/2004-4065S1_08_FDA-Hammad.ppt (accessed 2005 Dec 2).

- 30.Shaffer D, Craft L. Methods of adolescent suicide prevention. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(2 Suppl):70-4. [PubMed]

- 31.Isacsson G. Suicide prevention — A medical breakthrough? Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000;102:113-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Olfson M, Shaffer D, Marcus SC, et al. Relationship between antidepressant medication treatment and suicide in adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:978-82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Hall WD, Mant A, Mitchell PB, et al. Association between antidepressant prescribing and suicide in Australia, 1991-2000: trend analysis. BMJ 2003;326:1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Valuck RJ, Libby AM, Sills MR, et al. Antidepressant treatment and risk of suicide attempt by adolescents with major depressive disorder. CNS Drugs 2004;18:1119-32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Gray D, Moskos M, Keller T. Utah Youth Suicide Study new findings. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Suicidology; 2003; Sante Fe.

- 36.Isacsson G, Homgren P, Ahlner J. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and the risk of suicide: a controlled forensic database study of 14857 suicides. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;111:286-90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Leon AC, Marzuk PM, Tardiff K, et al. Paroxetine, other antidepressants, and youth suicide in New York City: 1993 through 1998. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:915-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Henriksson S, Boethius G, Isacsson G. Suicides are seldom prescribed antidepressants: findings from a prospective prescription database in Jamtland county, Sweden, 1985-95. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001;103:301-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Shaffer D, Waslick B. The many faces of depression. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2002.