Abstract

We describe identification and characterization of a novel two-copy gene of the parasitic protozoan Leishmania that encodes a nuclear protein designated LNP18. This protein is highly conserved in the genus Leishmania, and it is developmentally regulated. It is an alanine- and lysine-rich protein with potential bipartite nuclear targeting sequence sites. LNP18 shows sequence similarity to H1 histones of trypanosomatids and of higher eukaryotes and in particular with histone H1 of Leishmania major. The nuclear localization of LNP18 was determined by indirect immunofluorescence and Western blot analysis of isolated nuclei by using antibodies raised against the recombinant protein as probes. The antibodies recognized predominantly a 18-kDa band or a 18-kDa-16-kDa doublet. Photochemical cross-linking of intact parasites followed by Western blot analysis provided evidence that LNP18 is indeed a DNA-binding protein. Generation of transfectants overexpressing LNP18 allowed us to determine the role of this protein in Leishmania infection of macrophages in vitro. These studies revealed that transfectants overexpressing LNP18 are significantly less infective than transfectants with the vector alone and suggested that the level of LNP18 expression modulates Leishmania infectivity, as assessed in vitro.

Leishmania spp. are obligately intracellular protozoan parasites that are members of the family Trypanosomatidae, and they cause a wide spectrum of human diseases of major health importance, ranging from self-healing cutaneous lesions to severe visceral leishmaniasis or kala-azar with a high fatality rate (13). These parasites have two developmentally distinct stages; the amastigotes are nonmotile forms that survive and replicate within mammalian host macrophages, and the motile flagellated promastigotes survive and replicate inside the insect vector (13).

During the last several years, considerable interest has been focused on an extensive study of the biology of these kinetoplastid protozoans, which are among the most primitive eukaryotes (48). Leishmania has assumed importance in molecular biology by virtue of the unusual nature of its gene organization and expression (39). The unusual features include the presence of multiple copies of the same gene organized in tandem arrays or adjacent genes encoding different proteins, which are often transcribed as large polycistronic precursors of mature mRNAs (32, 37), RNA editing, and transsplicing (38, 47). Leishmania molecular genetic studies have provided new insights into the mechanisms of gene expression (reviewed in reference 38). However, very little is known about gene regulation in these protozoans.

In all eukaryotic cells, the DNA is highly compacted due to its association with histone proteins (33). The basic structural unit of chromatin is the nucleosome, which comprises DNA wrapped tightly around an octameric-histone core having a tripartite organization consisting of a central (H3-H4)2 tetramer flanked by two H2A-H2B dimers (1). Histones, despite their low sequence homology, have a common motif, the histone fold (1, 2), which is considered to be a general protein dimerization motif. Most of the proteins classified in the histone fold superfamily are involved in protein-protein and/or protein-DNA interactions (2, 6). This motif is found in a wide variety of transcriptional activators resembling histones (11), such as the archaeal DNA-binding proteins HMf, HMt, and HMv (54), the CCAAT-specific transcription factor CBF (60), and the TAFII42 and TAFII62 subunits of the TFIID transcriptional complex of Drosophila (30). The linker histones H1 and H5 are essential for the organization of nucleosomes into a higher-order structure (43, 55). Like the relationship of core histones, a relationship between linker histones and transcription factors has also been suggested (16, 35).

There is great interest in histone genes in trypanosomatids because in these organisms chromatin is not condensed into chromosomes during cell division but remains decondensed as fine fibers. However, the DNA is associated, probably weakly, with all classes of histones and is packed into nucleosomes (4). Characterization and systematic studies of the Trypanosoma genes coding for histones (3, 8, 25, 42), as well as the Leishmania genes coding for histones (21, 26, 52, 53), have shown that the sequence similarity with the genes coding for histones in higher eukaryotes is low (reviewed in reference 24). In particular, the H1 histones of trypanosomatids have significantly lower molecular masses than the H1 histones of higher eukaryotes, and there is only 43.6% similarity between the Trypanosoma cruzi and human H1 sequences. Moreover, in contrast to the histone genes of higher eukaryotes, trypanosomatid histone genes are located on different chromosomes, and their transcripts are polyadenylated. Although histone genes and their expression in trypanosomatids have been studied extensively, little is known about the regulation of their expression (reviewed in reference 24).

In this paper we describe molecular cloning and characterization of a novel histone H1-like Leishmania nuclear DNA-binding protein, LNP18, and present evidence that LNP18 plays a role in Leishmania infectivity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vitro culture of Leishmania.

Promastigotes were grown at 26°C in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Gibco) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum. The following strains were used in this study and in previous studies: Leishmania major LV39 and Leishmania infantum HOM-Gr78L4, isolated in Greece (57, 58); and Leishmania amazonensis LV78, kindly provided by K.-P. Chang. Amastigotes were isolated from lesions (at least 2 months old) of BALB/c mice infected with 1 × 106 stationary-phase L. major promastigotes by using established protocols (28).

Screening of a cDNA library and DNA sequence analysis.

An L. major cDNA library was constructed in the lambda Uni-ZAP XR vector as described in the technical manual provided by Stratagene Inc. (La Jolla, Calif.). Poly(A)+ mRNA from L. major promastigotes was used to synthesize cDNAs. A cDNA clone that was recognized by affinity-purified antibodies raised against the purified Leishmania transferrin receptor molecule (59) was isolated and sequenced. Leishmania cDNAs in the Uni-ZAP XR vector were subsequently plated on Escherichia coli XL-1 Blue cells, and the phagemids were excised by the methods described in the manufacturer's protocol manual (Stratagene Inc.). Subsequently, plasmid DNA from the phagemids was isolated and sequenced by using standard procedures (45).

Southern and Northern blot hybridization analyses.

DNAs were isolated from promastigotes, digested to completion (3 h at 37°C) with endonuclease XbaI (5 U/μg of DNA), electrophoresed in 0.8% agarose containing 45 mM Tris, 45 mM boric acid, and 1 mM EDTA (pH 8), and transferred to nylon membranes; the agarose was stained with ethidium bromide. Plasmid DNA in Leishmania cells was isolated by the alkaline lysis method (51). Total cellular RNA was extracted from Leishmania promastigotes by the hot acid phenol method as modified by Brown and Kafatos (10). For Northern blot analysis, total parasite RNA was electrophoresed through a 1.2% (wt/vol) agarose gel containing formaldehyde and was subsequently transferred to blotting membranes (Zetaprobe; Bio-Rad).

Hybridization and washing for either DNA or RNA analysis were carried out as previously described (51). Filters were hybridized overnight at 65°C with 32P-labeled cDNA probes, labeled by the random priming method (22), in hybridization solution containing 1% crystalline grade bovine serum albumin, 1 mM Na2 EDTA, 0.5 M NaH2PO4 (pH 7.2), and 7% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). The filters were washed as described by Church and Gilbert (14). The membranes were autoradiographed on X-OMAT AR film (Kodak) at −80°C with two intensifying screens. For rehybridization of a membrane, the probe was eluted by two washes with 2 mM Tris-EDTA (pH 8.2)-0.1% (wt/vol) SDS for 15 min at 95°C.

The amounts of RNA loaded on filters were estimated by ethidium bromide staining of agarose gels loaded with equivalent amounts of the samples, as well as by staining the nitrocellulose filters with methylene blue in order to evaluate the amounts of transferred rRNAs.

Probes.

The following probes were used in this study: pBS10Rb.1, containing a 2.2-kb EcoRI fragment from an L. major gp63 cDNA clone (12), kindly provided by L. Button and R. McMaster (Medical Genetics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada); and T11, containing a 2-kb PstI fragment from an L. amazonensis β-tubulin cDNA clone, T11 (23), kindly provided by K.-P. Chang (Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Health Sciences, The Chicago Medical School, North Chicago, Ill.).

Production of antibodies.

Anti-LNP18 antibodies were obtained from rabbits immunized with recombinant LNP18 (rLNP18). rLNP18 was produced by using the pRSET-E Echo cloning system (Invitrogen, Groningen, The Netherlands). In the Echo cloning system a one-step cloning strategy is utilized for direct insertion of a PCR product into an appropriate plasmid vector, and the classic cloning procedures are not required. The fusion plasmid was transformed into TOP10 cells, and positive clones were analyzed. To confirm the fusion junctions, isolated plasmid DNA was analyzed by restriction analysis and sequencing. After overexpression in E. coli, rLNP18 was purified by affinity chromatography on Ni2+-nitrilotriacetate resin columns under denaturing conditions by following the supplier's instructions (Qiagen). Two New Zealand White rabbits were immunized subcutaneously three times every 2 weeks with 50 μg of rLNP18. Affinity-purified anti-LNP18 antibodies were isolated by low-pH elution from immunoblots of purified rLNP18 as previously described (59).

Gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was performed on 12.5% polyacrylamide gels by the method of Laemmli (34). The separated proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose, and a Western blot analysis (56) was carried out essentially as previously described (50). The filters were blocked overnight at 4°C with 5% powdered nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline. After incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, the filters were developed in diaminobenzamidine with nickel enhancement (0.03% [wt/vol] DAB and 0.03% [wt/vol] NiCl2 in Tris-buffered saline).

Nucleus preparation.

Nuclei were prepared as described by Hinterberger et al. (29). Briefly, stationary-phase promastigotes (109 cells) were washed and lysed in 6 ml of NB buffer containing 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 250 mM sucrose supplemented with 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in a Dounce homogenizer. The lysate was centrifuged (20 min, 1,900 × g), and the resulting pellet was washed in NB buffer and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 90 min at 4°C over a 2 M sucrose cushion in NB buffer containing 0.5% (wt/wt) Triton X-100. The nuclear pellet was subsequently washed and resuspended in 50 mM HEPES-5 mM MgCl2-2 mM dithiothreitol-1 mM EDTA containing 40% (vol/vol) glycerol.

Immunofluorescence staining.

Promastigotes (106 cells/ml) were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed on glass microscope slides as previously described (49). Antibodies were diluted in PBS containing 0.3% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin. The primary antibody was then applied overnight at 4°C, and the fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibody was applied for 30 min at room temperature. After immunostaining, coverslips were mounted on the glass slides in 90% glycerol in PBS, and the preparations were viewed either with a Zeiss Axiophot photomicroscope or with a Leica laser scanning confocal microscope.

In vitro UV cross-linking of nucleic acids to proteins.

For in vitro cross-linking of DNA to proteins, we used the approach used by Pelle and Murphy (41). Briefly, isolated nuclei from approximately 5 × 109 L. major promastigotes were homogenized on ice in 200 μl of homogenization buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA; pH 8) in a Dounce homogenizer. The lysate was centrifuged (20 min, 1,900 × g), and the resulting nuclear extract was subsequently digested with 5 U of Sau3AI per μl. Ten microliters of the nuclear extract in 400 μl of 25 mM HEPES-120 mM NaCl-6 mM KCl-2 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.4) was incubated at room temperature for 20 min before UV irradiation. Irradiation was carried out with 254-nm UV light for 20 min at 4°C. After UV treatment, 2 volumes of cold ethanol was added, and the precipitate was pelleted by centrifugation. The resulting pellet was dissolved in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, and then separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting by using the anti-LNP18 antibodies as probes. For the control we used samples treated with 100 U of DNase I per ml before or after UV cross-linking and samples prepared by a procedure from which the irradiation step was omitted.

Plasmid constructs.

The pX63-HYG leishmanial expression vector (17) was kindly provided by S. Beverley. The cDNA of LNP18 was end filled with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I (New England Biolabs, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom) and cloned into the SmaI restriction site of the pX63-HYG polylinker.

Transfection of Leishmania.

L. major LV39 stationary-phase parasites were transfected with approximately 10 μg of pX63-HYG carrying the LNP18 gene and with pX63-HYG alone as a control. Cells were subjected to electroporation with a Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad) by using established protocols. After 24 h of recovery in hygromycin B-free medium 199, resistant cells were selected in the presence of increasing concentrations of hygromycin B (up to 500 μg/ml).

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from transfected LV39 promastigostes by using an RNeasy kit for RNA isolation (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA synthesis and a PCR were performed in an one-step reaction by using the Titan one-tube reverse transcription (RT)-PCR system (Roche). For PCR the following LNP18- and β-actin-derived oligonucleotides were used: LNP18F (5′-AGGTGGCTACGCCGAAGAAGC-3′) and LNP18R (5′-ACTGCGGACGAAGTAGACAC-3′); and β-actinF (5′-GACTCCTATGTGGGTG ACGAGG-3′) and β-actinR (5′-GGGAGAGCATAGCCCTCGTAGAT-3′). Each PCR was performed in a 50-μl reaction mixture containing 10 μl of RT-PCR buffer, 25 pmol of each primer, 5 μl of a solution containing each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 2.5 mM (Promega), and 1 μl of enzyme mixture. In addition, 0.5 μl of an RNase inhibitor (RNasin; 40 U/μl; Promega) was added. The amplification cycle (denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and extension at 68°C) was repeated 30 times, and this was followed by a 7-min final extension step.

Infection of macrophages.

Macrophages of the J774 line (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) were plated in 96-well flat-bottom microculture plates at a concentration of 106 cells/ml of medium 199. Lesion-derived L. major promastigotes (wild type, transfected with vector pX63-HYG alone and with pX63-HYG carrying the LNP18 cDNA) were used in infection studies at a ratio of 10 parasites per cell. The microculture plates were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 5 h. After removal of nonadherent parasites, the macrophages were washed three times and incubated for an additional 72 h. The cultures were then washed with medium, lysed with 100 μl of 0.01% SDS/well, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min (62). Schneider's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum was added, and the released parasites were incubated at 26°C for 48 h. Cultures were subsequently pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine per well, and the radioactivity incorporated was counted with a β-counter. The results were expressed as means ± standard errors of the means. Data from three infection experiments were pooled.

Flow cytometry.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis was performed for 12,000 events, and numeric data were processed with Cellquest software. An analysis of infected and noninfected macrophages was performed as described by Di Giorgio et al. (18) by using antibodies generated against LV39 lesion-derived amastigotes. Cells were incubated with antibodies in permeabilization buffer (0.1% sodium azide, 1% bovine serum albumin, 1% fetal calf serum, and 0.1% saponin in PBS [pH 7.4]) and then with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulins (1:1,000; Sigma). Cells were washed two times and were analyzed with a FacSort analytical cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the EMBL, GenBank, and DDBJ databases under accession number LMA237814.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of the LNP18 cDNA.

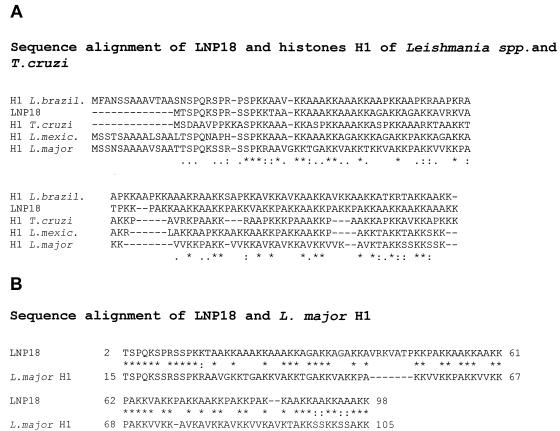

In an effort to clone and characterize the Leishmania transferrin receptor gene, a molecule that was first identified in our laboratory (59), a cDNA clone encoding a novel protein, LNP18, was accidentally identified and subsequently sequenced. Figure 1 shows the complete nucleotide sequence of the 0.690-kb cDNA insert and the deduced amino acid sequence. The deduced amino acid sequence predicts a basic protein (pI 12.2) containing 98 amino acids and having a predicted molecular mass of 9.9 kDa. The LNP18 predicted amino acid sequence was compared with the sequences of proteins listed in SBASE by advanced BLAST. This search revealed that LNP18 belongs to the histone H1-histone H5 family. Interestingly, LNP18 shows significant similarity with H1 histones of members of the Trypanosomatidae. Sequence alignments for LNP18 and the H1 histones of T. cruzi and other Leishmania species, obtained by using CLUSTALW, are shown in Fig. 2A. It should be noted that H1 histones in eukaryotes are less conserved than the core histones and exhibit a high degree of variability. Moreover, H1 histones in members of the Trypanosomatidae have much lower molecular masses than their eukaryotic counterparts and exhibit exclusive motifs characteristic of the C-terminal domain of eukaryotic H1 histones (reviewed in reference 24). Galanti et al. found 43.6% similarity between T. cruzi H1 and the C-terminal region of human H1 (24). Furthermore, the L. major (21) and T. cruzi H1 histones (24) exhibit 61.79% similarity (data not shown). The sequence of LNP18 was compared with that of L. major histone H1. This comparison (Fig. 2B) showed that 61% of the residues are either identical (56%) or well conserved (5%). Thus, LNP18 is a histone H1-like protein.

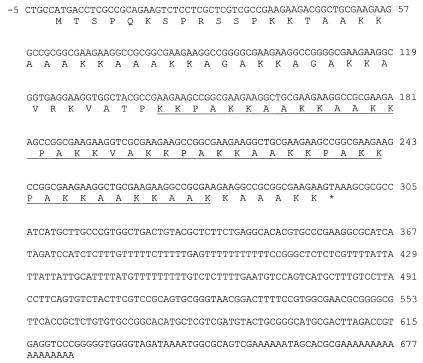

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence of L. major LNP18 cDNA. The deduced amino acid sequence is indicated below the DNA sequence. The domain that contains the eight potential sites of bipartite nuclear sequences (bipartite nuclear localization signals) is underlined. The amino acid sequence is indicated by the single-letter amino acid code.

FIG. 2.

(A) Alignment of amino acid sequences of trypanosomatid histones H1 and LNP18. (B) Alignment of LNP18 and L. major histone H1 (19) sequences. The asterisks, colons, and dots indicate aligned residues that are identical, very similar, and similar, respectively. Gaps (dashes) were introduced for optimal alignment. The numbers at the beginning and the end of a line indicate amino acid positions in the parent proteins. L.brazil., L. braziliensis; L.mexic., L. mexicana.

Analysis of the sites and signatures of the LNP18 amino acid sequence revealed that it is an alanine- and lysine-rich protein with eight potential sites of bipartite nuclear localization signals (Fig. 1). Bipartite nuclear localization signals are known to be necessary for nuclear targeting (5, 19, 44, 63). Interestingly, the same motif is present in almost one-half the nuclear proteins in the Swiss protein database but in less than 5% of the nonnuclear proteins, and many of these proteins are secreted or targeted to other organelles. An example of a molecule having a relatively low molecular mass (143 residues) that has a functional nuclear localization signal-like motif is human gamma interferon (63). A hydrophobicity analysis performed by using PC GENE suggests that LNP18 is a globular protein (data not shown).

Genomic organization and expression of the LNP18 gene: Southern and Northern analyses.

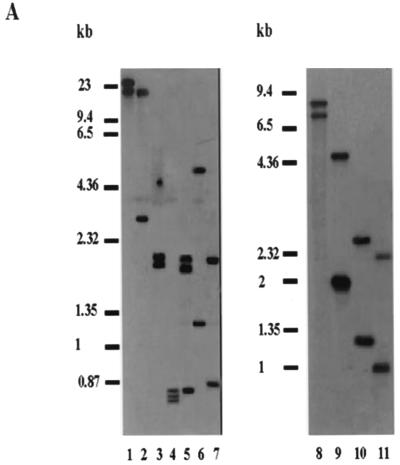

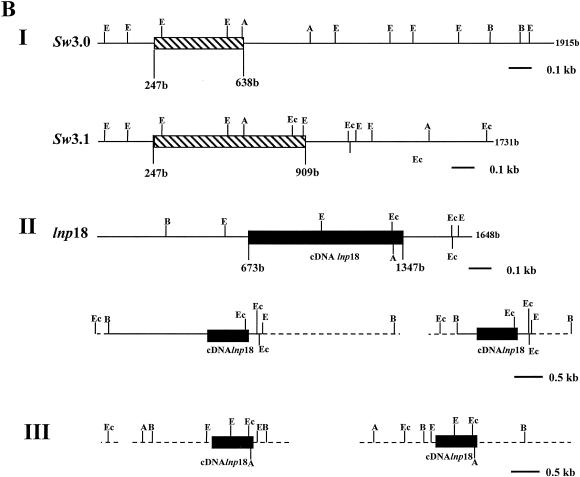

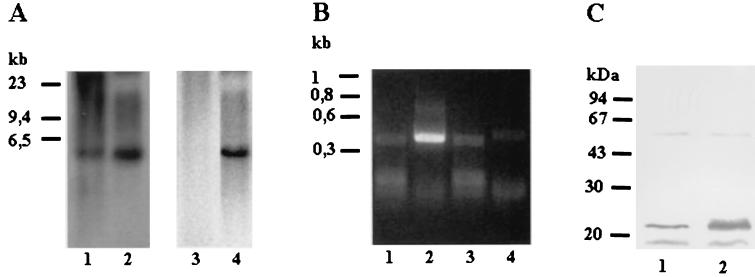

Southern blot analysis was performed to determine the copy number of the LNP18 gene by using genomic DNAs from L. major and L. infantum promastigotes. The DNAs were digested with the following restriction enzymes, separately or in combination: EcoRI, HindIII, and BglI, which have no internal sites within the cDNA; and Eco0109I and AvaI, which have one internal site. As shown in Fig. 3A, digestion with enzymes having no internal sites within either the L. major cDNA (lanes 1 to 3) or the L. infantum genomic DNA (lanes 8 and 9) resulted in two bands when the preparations were hybridized (under highly stringent conditions) with a probe containing the complete LNP18 cDNA. If the physical maps of sw3.0 and sw3.1 and the physical map of LNP18 (Fig. 3B) are taken into account, the possibility of cross-hybridization of the LNP18 cDNA probe with fragments of the two L. major histone H1 genes cannot be excluded. However, it has been reported that when the sw.3 open reading frame is used as a probe in Southern blots, it does not detect any digests in Leishmania donovani, a species that belongs to the same complex as L. infantum (7). This finding supports the assumption that at least in L. infantum the two fragments detected correspond to digests of the LNP18 locus. When the L. major DNA was digested with AvaI (Fig. 3A, lane 5), three bands, at1.9, 1.75, and 0.85 kb, were observed; the 0.85-kb band probably corresponds to an sw3.1 fragment of the L. major H1 gene (Fig. 3B, map I). BglI digestion resulted in two bands, at 2 and 1.8 kb (Fig. 3A, lane 3). However, AvaI-BglI double digestion resulted in a 0.85-kb band (Fig. 3A, lane 4) that could correspond to the AvaI fragment detected in Fig. 3A, lane 5. The possibility that this fragment could be a digestion product of the sw3 locus that cross-hybridized with the LNP18 probe, due to the high homology of the two genes, cannot be excluded. However, two of the three bands detected in Fig. 3A, lane 4 (the 0.75- and 0.7-kb bands), cannot be attributed to fragments of L. major H1, since there are no internal BglI sites in the AvaI fragments of the two H1 gene sequences in the region that shows homology to the LNP18 cDNA probe (Fig. 3B). The latter finding is consistent with the hypothesis that L. major LNP18 is a two-copy gene.

FIG. 3.

(A) Southern blots of L. major (lanes 1 to 7) and L. infantum (lanes 8 to 11) genomic DNAs digested with various restriction enzymes. Blots were hybridized with LNP18 cDNA. The following restriction enzymes were used: HindIII (lanes 1 and 8); HindIII and EcoRI (lane 2); BglI (lanes 3 and 9); BglI and AvaI (lane 4); AvaI (lane 5); Eco0109I (lanes 6 and 10); and BglI and Eco0109I (lanes 7 and 11). (B) Map I is a physical map of L. major H1 (copies sw3.0 and sw3.1) and the L. infantum LNP18 gene (EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ accession no. AJ223860, AJ223861, and AF469106, respectively). Map II is a physical map of the sequenced gene of L. infantum and of the two copies of the L. infantum LNP18 gene deduced from both Southern blot analysis (panel A, lanes 8 to 11) and restriction enzyme analysis of the sequenced LNP18 DNA gene. Map III is a physical map of the two copies of L. major LNP18 deduced from Southern blot analysis (panel A, lanes 1 to 7) and restriction enzyme analysis of the sequenced LNP18 cDNA. The cross-hatched boxes indicate the homology of sw3.1 and sw3.0 to the cDNA of L. major LNP18. The solid boxes correspond to the LNP18 cDNA sequence in both species. The dashed lines represent DNA that has not been sequenced yet. Enzyme abbreviations: E, EarI; A, AvaI; B, BglI; Ec, Eco0109I.

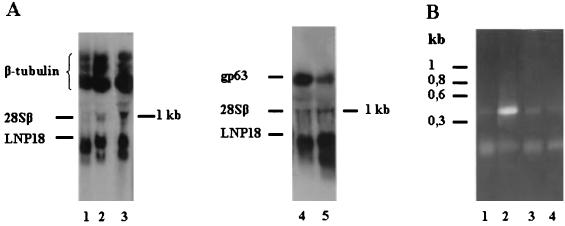

Transcription of the gene was confirmed by Northern blot analysis of total RNAs extracted from diverse species of Old World and New World Leishmania promastigotes. As shown in Fig. 4A, under highly stringent conditions the probe recognized two transcripts (approximately 0.8 and 0.7 kb). The sizes of these transcripts are consistent with the size of the reported full-length cDNA. These two transcripts may be due to multiple polyadenylation sites or to two closely related genes or copies.

FIG. 4.

(A) Northern blot analysis of total RNAs extracted from promastigotes of different species of Leishmania (L. amazonensis, L. tropica, L. donovani, and L. major [lanes1 to 3 and 5, respectively]) and L. major amastigotes (lane 4), separated on a 1.2% (wt/vol) agarose-formaldehyde gel. After blotting, the filters were hybridized either with LNP18 cDNA and the β-tubulin probe (lanes 1 to 3) or with LNP18 cDNA and the gp63 probe (lanes 4 and 5) and autoradiographed. The marker on the right indicates the size and mobility of 28Sβ rRNA. (B) RT-PCR analysis of amastigotes and promastigotes. Total RNA isolated from promastigotes (lanes 1 and 2) or amastigotes (lanes 3 and 4) was reversed transcribed, and primers derived from LNP18 (lanes 2 and 4) and β-actin (lanes 1 and 3) were used. The positions of size markers are indicated on the left.

Subsequently, we examined the level of expression of LNP18 in the amastigote stage of L. major parasites (Fig. 4A, lane 4). Estimation of the amount of RNA transferred onto filters, as described in Materials and Methods, showed that the level of amastigote RNA was at least four times higher than the level of promastigote RNA. On the other hand, the level of the 0.8-kb transcript in L. major promastigotes was 15- to 20-fold higher than the corresponding level in amastigotes, as determined by scanning densitometry of a blot that was exposed for a shorter period of time (data not shown). This was evaluated by simultaneously hybridizing the filter with the LNP18 cDNA probe and a 2.2-kb EcoRI fragment from L. major gp63 cDNA. gp63 is down-regulated at both the mRNA and protein levels in amastigotes. Interestingly, only one transcript (0.8 kb) was detected in L. major amastigotes, but the level was significantly lower (Fig. 4A, lane 4). Most probably the transcript detected was due to cross-hybridization of the LNP18 probe with the histone H1 transcript due to overloading of the gel. Histone H1 is up-regulated in amastigotes compared to promastigotes (21, 40).

The level of expression of LNP18 in amastigotes was also analyzed by RT-PCR. To do this, RNAs were isolated from lesion-derived amastigotes and promastigotes and were amplified by using primers designed from the LNP18 open reading frame. Using this approach, we showed that LNP18 expression was significantly lower in amastigotes than in promastigotes (Fig. 4B, lanes 4 and 2, respectively). Importantly, LNP18 protein was not detected in L. major amastigotes (Fig. 5B). The significance of this finding is discussed below.

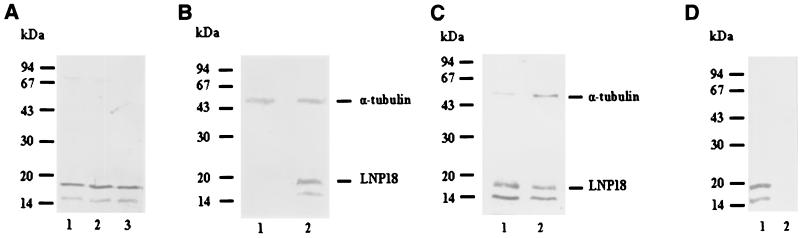

FIG. 5.

(A) Gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting of L. major, L. infantum, and L. amazonensis promastigotes (lanes 1 to 3, respectively) probed with antibodies raised against the recombinant protein (anti-rLNP18). The positions of molecular size standards are indicated on the left. (B) Western blot analysis of lysates from lesion-derived amastigotes (lane 1) and promastigotes (lane 2). Lysates were separated by SDS-15% PAGE, electroblotted, and probed with anti-rLNP18 and α-tubulin antibodies (NeoMarkers). The positions of molecular size standards are indicated on the left. (C) Western blot analysis of L. major promastigotes grown to the early logarithmic phase (day 3) (lane 2) and the stationary phase (day 5) (lane 1). The blot was probed with anti-rLNP18 and α-tubulin antibodies. (D) L. major isolated nuclei and cytoplasmic extracts from the same number of parasites (lanes 1 and 2, respectively). SDS-PAGE was performed under reducing conditions on 12.5% polyacrylamide gels. The positions of molecular size standards are indicated on the left. (E and F) Immunofluorescence labeling of promastigotes when the anti-rLNP18 antibodies were used as probes. L. major promastigotes (1.5 × 10 6 cells/ml of PBS) were fixed on glass microscope slides. Binding of anti-rLNP18 in the nucleus was visualized by using a secondary antibody conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and either phase-contrast microscopy performed with a photomicroscope (E) or confocal laser microscopy (F). For confocal microscopy an overlay image is also shown.

Identification and localization of native Leishmania LNP18.

Anti-LNP18 antibodies, generated by using rLNP18, recognized in Western blots of L. major lysates an 18-kDa protein or an 18-kDa-16-kDa doublet (Fig. 5A, lane 1). The antibodies recognized the same bands for different Leishmania species, indicating that LNP18 is a highly conserved protein (Fig. 5A). The LNP18 antibodies do not seem to cross-react with the closely related H1 protein, since they do not recognize any polypeptides in lesion-derived amastigotes (Fig. 5B lane 1); it has been demonstrated in several studies that expression of H1, at both the mRNA and protein levels, is significantly higher in lesion-derived amastigotes than in L. major promastigotes (21, 40). In order to ensure that the amount of amastigote protein transferred was sufficient to detect LNP18, blots were cohybridized with antibodies against α-tubulin, a protein that is down-regulated in the amastigote stage of L. major (15). The fact that the intensities of α-tubulin in the two stages were comparable suggests that the amount of protein loaded in lane 1 (amastigotes) of Fig. 5B was severalfold higher than the amount of protein loaded in lane 2 (promastigotes). Even under these experimental conditions LNP18 was not detected in amastigotes. Therefore, the difference in the level of expression of LNP18 between the two stages is even greater than the difference shown in Fig. 5B.

The molecular mass of purified rLNP18 was also estimated to be 18 kDa (data not shown), a value that is significantly higher than the value expected from the deduced amino acid sequence. It should be noted that it is becoming increasingly evident that very basic or acidic proteins may migrate anomalously on SDS-PAGE gels (31). Therefore, the anomalous migration of LNP18 might be due to abnormal binding of SDS to basic amino acids, since LNP18 is a Lys-rich basic protein, which in turn might lead to an abnormal shape of the SDS-protein complex. It should be pointed out that anomalous migration of LNP18 in SDS-PAGE gels is a common characteristic of histone H1 of L. major. The amino acid sequence of the latter protein deduced from the cDNA predicts that the protein has 105 amino acid residues. However, specific antibodies recognize a 17-kDa-19-kDa doublet in different L. major strains (40). Like H1 polymorphism, LNP18 size polymorphism may reflect the presence of LNP18 variants possessing common epitopes. Moreover, Western blot analysis of the transfectants overexpressing LNP18 showed that the bands detected were derived from the cloned cDNA (Fig. 6C, lane 2).

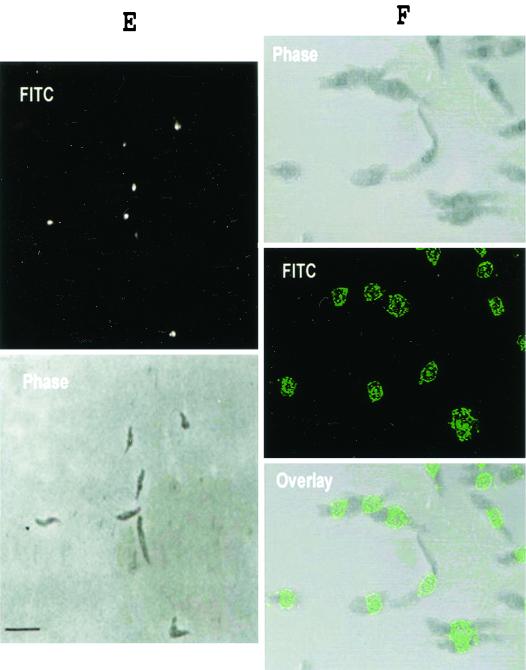

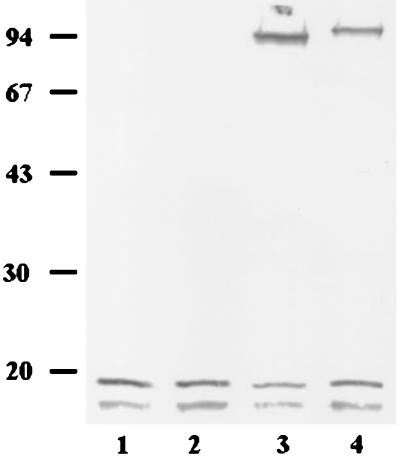

FIG. 6.

Monitoring LNP18 expression in transfected LV39 parasites. (A) Southern blot analysis of extrachromosomal DNA isolated from parasites transfected with pX63-HYG and from parasites transfected with pX63-HYG-LNP18 (lanes 1 and 3 and lanes 2 and 4, respectively). The DNA (5 μg per lane) was digested with BglI and probed with the BamHI-EcoRI fragment of the HYG coding region (lanes 1 and 2). The membrane was stripped and reprobed with the LNP18 coding region (lanes 3 and 4). The positions of size markers are indicated on the left. (B) RT-PCR analysis of the transfectants. Total RNA extracted from parasites transfected with either pX63-HYG-LNP18 (lanes 1and 2) or pX63-HYG (lanes 3 and 4) was reversed transcribed by using the LNP18-derived primers (lanes 2 and 4) and the β-actin-derived primers (lanes 1 and 3), which were used as a control. The positions of size markers are indicated on the left. (C) Immunoblot analysis of transfected LV39 total lysates (lane1, pX63-HYG; lane 2, pX63-HYG-LNP18). The blot was probed with anti-LNP18 and anti-α-tubulin antibodies (used as a loading control). The positions of standard size markers are indicated on the left.

Sequence analysis of L. infantum LNP18 genomic clones and comparison with the L. major LNP18 cDNA sequence revealed a putative initiation codon 39 nucleotides immediately upstream of the codon proposed for L. major LNP18. Since the open reading frames of the two genes are identical, we cannot eliminate the possibility that this in-frame ATG could be the translation start codon for both genes. In such a case the molecular mass of the deduced amino acid sequence would be slightly larger (11 kDa; 111 amino acids with a pI of 11.74) than the predicted Mr of L. major (9.9 kDa). This analysis further supports the hypothesis that the proteins detected are the products of the LNP18 gene.

LNP18 expression was also investigated during in vitro growth of promastigotes from the logarithmic phase to the stationary phase (that is, as promastigotes differentiate from a noninfective stage to an infective stage) (Fig. 5C). An α-tubulin antibody was used to examine whether LNP18 is differentially expressed during parasite differentiation. The housekeeping gene is down-regulated twofold in stationary-phase promastigotes compared to log-phase promastigotes (15). Densitometry analysis of both α-tubulin bands and LNP18 bands for the two developmental stages revealed ratios of 3.5 (lane 2 versus lane 1) and 1.7 (lane 1 versus lane 2), respectively. These data, combined with the known down-regulation of the α-tubulin protein, suggest that the LNP18 level increases threefold during promastigote maturation in culture.

The observed sequence similarity of LNP18 and H1 histones prompted us to investigate the possible nuclear localization of LNP18. Western blot analysis of Leishmania isolated nuclei (Fig. 5D) and staining of whole promastigotes by indirect immunofluorescence (Fig. 5E), when the anti-LNP18 antibodies were used as probes, showed that the protein is located exclusively in the nucleus (Fig. 5D, lane 1). To obtain a better idea of the LNP18 localization, we performed confocal microscopy (Fig. 5F). No protein was detected in the cytoplasmic extracts (Fig. 5D, lane 2) or the cytoplasm of whole parasites (Fig. 5E and F) with either approach. Ponceau S staining of membranes after protein transfer confirmed that the amounts of protein transferred to nitrocellulose were equivalent (data not shown).

In vitro UV-cross-linking hybridization: detection of an LNP18-DNA complex.

In order to demonstrate that LNP18, which has characteristics of a DNA-binding protein, does interact with Leishmania DNA, we used the UV-cross-linking hybridization technique (41). Nuclear extracts were irradiated as described in Materials and Methods. UV irradiation induces cross-links between nucleic acids and proteins in close contact. This method has an additional advantage, its specificity. Thus, boiling extracts from irradiated cells in the presence of SDS causes the dissociation of any nonspecific nucleic acid-protein complexes. After UV treatment, samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting. Hybridization of the blot with the anti-LNP18 antibodies revealed an approximately 94-kDa band (Fig. 7, lane 4). In contrast, the 94-kDa band was not detected when samples were treated with DNase I prior to UV treatment and when nonirradiated nuclear control samples were used (Fig. 7, lanes 2 and 1, respectively). Treatment with DNase I after UV cross-linking slightly affected the migration of the 94-kDa complex. Most probably the resulting 90-kDa band (lane 3) corresponds to a DNA-protein complex. Hence, by using this simplified method which induces cross-links between nucleic acids and proteins in close contact, we showed that LNP18 is a potential DNA-binding protein.

FIG. 7.

In vitro UV-cross-linking analysis of nuclear L. major extracts. UV irradiation and Western blot analysis of the extracts were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1, DNase I treatment prior to UV treatment; lane 2, nontreated extracts used as a control; lane 3, UV treatment followed by DNase I treatment; lane 4, UV treatment.

Modulation of LNP18 level.

Together, our data indicate that LNP18 has interesting features that make its function implicit. Therefore, we developed L. major transfectants in which the endogenous level of LNP18 was modulated. This was accomplished by transfecting L. major promastigotes with a plasmid construct developed by cloning the cDNA of LNP18 in the sense orientation into the SmaI restriction site of the pX63-HYG polylinker. Transfectants with the LNP18 cDNA and transfectants with the vector alone, developed in parallel, were selected in medium 199 with hygromycin B at a final concentration of up to 500 μg/ml. The integrity of the plasmids in these transfectants was confirmed by restriction mapping and sequencing, as well as by Southern blot analysis with specific probes (Fig. 6A). As expected, semiquantitative RT-PCR performed with RNA isolated from the transfectants showed significantly higher levels of LNP18 RNA in the pX63-HYG-LNP18 transfectants than in the transfectants with the vector alone (Fig. 6B, lanes 2 and 4, respectively). The level of LNP18 protein was significantly increased (approximately four- to fivefold) in the pX63-HYG-LNP18 transfectants compared to the control (Fig. 6C). This was estimated by densitometry analysis of the intensity of the LNP18 18-kDa-16-kDa doublet in controls and transfectants overexpressing LNP18 compared with the intensity of α-tubulin.

Infection of mouse macrophages.

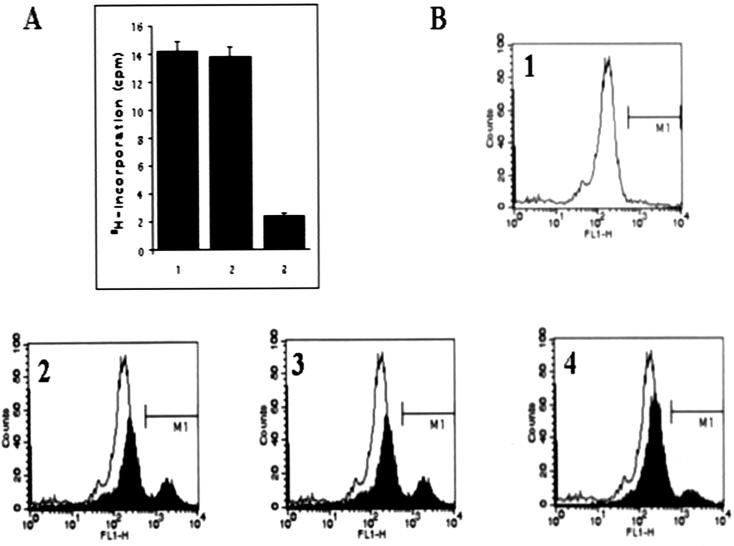

Macrophages (cell line J774) cultured in 96-well plates were infected at a ratio of 10 parasites per cell for 5 h with stationary-phase wild-type strain LV39 promastigotes and with LNP18-overexpressing and control plasmid-containing transfectants. The growth rate of amastigotes within macrophages was subsequently monitored. There was no difference in the ability to invade macrophages, the number of infected macrophages, or the number of intracellular parasites during the first 24 h of infection. This was evaluated by cytospin and Giemsa staining of cells (data not shown). However, as shown in Fig. 8A, the number of amastigotes released from macrophages (transformed into promastigotes when they were incubated at 26°C for 48 h) infected with the LNP18 transfectants was significantly lower (sevenfold lower) than the number of parasites released from macrophages infected with promastigotes containing the control plasmid and with wild-type promastigotes. Similar results were obtained in three separate experiments performed with parasites generated in two transformation experiments.

FIG. 8.

In vitro infection assays. (A) Macrophages were infected with wild-type lesion-derived promastigotes and LV39 transfected with pX63-HYG and with pX63-HYG-LNP18 for 5 h, washed, and incubated for 72 h (lanes 1 to 3, respectively). The cultures were then washed with medium and lysed with 0.01% (wt/vol) SDS to release the surviving amastigotes, which were cultured for an additional 48 h. Cultures were subsequently pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine per well, and incorporation of radioactivity was counted with a β-counter. Data from three independent experiments (12 wells per transfectant or wild-type promastigotes) were pooled, and the standard errors are indicated by error bars. (B) Fluorescence-activated cell sorter histograms acquired with noninfected macrophages (histogram 1) and macrophages infected with LV39 wild type (histogram 2) and LV39 transfected with either pX63-HYG (histogram 3) or pX63-HYG-LNP18 (histogram 4). The macrophages were infected for 5 h, washed, and incubated for 72 h. The cultures were washed again and processed for fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis as described in Materials and Methods.

It should be noted that amastigotes released from macrophages transformed into promastigotes at 26°C grew in the presence of hygromycin B, indicating that they retained the plasmid. These results suggest that LNP18 affects intramacrophage survival and/or replication of these parasites.

The infection rates of the transfectants were also evaluated by flow cytometry. Amastigote-containing macrophages were detected with a polyclonal mouse antibody raised against amastigotes isolated from lesions of infected BALB/c mice and purified by low-pH elution of antibodies from strips blotted with amastigote lysates. By using this approach the infection rates in L. major-infected macrophages were measured with a high degree of specificity and reproducibility. The histogram in Fig. 8B clearly shows two well-defined populations corresponding to non-amastigote-containing cells and infected cells. The flow cytometric assay could not separate cells containing a single parasite from cells containing more than one amastigote. The accuracy and reproducibility of flow cytometry for detection of intracellular amastigotes, as well as tests for the efficacy of drugs against intracellular parasites, were recently examined in two independent studies (18, 27). The results of four independent experiments showed that the infectivity of the transfectants overexpressing LNP18 was significantly lower than that of the control plasmid-containing transfectants; the number of infected cells differed by threefold. The infectivity of the latter (approximately 35 to 40% of macrophages contained at least one amastigote) was comparable to that of wild-type parasites. The results obtained with both approaches strongly suggest that the level of expression of LNP18 modulates parasite infectivity.

DISCUSSION

In this paper we describe identification and characterization of a novel two-copy gene of Leishmania that encodes a developmentally regulated nuclear protein, designated LNP18. LNP18 is a DNA-binding protein that shows sequence similarity with H1 histones of trypanosomatids and, in particular, with histone H1 of L. major. It is recognized as a 18-kDa-16-kDa protein doublet which is highly conserved in the genus Leishmania. Both polypeptides appear to be related to LNP18 since analysis of transfectants overexpressing the gene showed that both polypeptides were up-regulated. Furthermore, the possibility that anti-LNP18 antibodies cross-react with the closely related L. major H1 protein must be excluded since the LNP18 antibodies do not seem to cross-react with the histone H1 protein in lesion-derived amastigotes (Fig. 5B, lane 1), in which the expression of H1, at both the mRNA and protein levels, is significantly higher than the expression of H1 in L. major promastigotes (21, 40). Like histone H1 polymorphism in L. major, LNP18 polymorphism may reflect the presence of variants possessing common epitopes, possibly as a result of posttranscriptional modification, a feature seen in H1 histones of higher eukaryotes (46).

Several lines of evidence suggest that functional significance underlies the heterogeneity of the H1 class of histones. In mice there are at least seven different H1 variants, which display different patterns of expression during development and differentiation (20). Thus, we investigated the expression profile of LNP18 during parasite growth and differentiation in vitro. The LNP18 level appeared to increase threefold as promastigotes differentiated from a noninfective stage to an infective stage and decreased severalfold in the amastigote stage, as assessed by Northern and Western blot analyses.

Infection of macrophages in vitro with transfectants overexpressing LNP18 showed that they are significantly less infective than the transfectants with the vector alone. These results suggest that the level of LNP18 expression modulates Leishmania infectivity. The mechanism by which the level of LNP18 expression affects Leishmania infectivity is not known yet. However, there is considerable evidence that histone H1 functions as a nonspecific repressor of transcription in higher eukaryotes and in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (36, 61). Similar observations have been made for the protozoan Tetrahymena, which is evolutionarily close to Leishmania. It has been shown that histone H1 is involved in the modulation of gene expression. Therefore, it is possible that LNP18 is involved in control of the expression of genes modulating Leishmania infectivity.

Recent findings also support the linkage of H1 expression with the cell cycle. In Trypanosoma brucei, H1 variants have been postulated to participate in the regulation of cell cycle progression and differentiation (3), as has been postulated for higher eukaryotes (9). Expression of LNP18, an H1-like protein, could be also linked to the cell cycle and gene expression and thus could control parasite differentiation and/or replication. Studies are in progress to define the functional role of this gene and protein in parasite growth and/or development. Moreover, the ability of transfectants to establish infections in vivo is currently being investigated.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Smirlis for critically reviewing the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Greek General Secretariat of Research and Technology and by the EU (INCO-DC contract ERBIC 18 CT 97-0252).

Editor: J. M. Mansfield

REFERENCES

- 1.Arents, G., R. W. Burlingame, B.-C. Wang, M. E. Love, and E. Moudrianakis. 1991. The nucleosomal core histone octamer at 3.1 Å resolution: a tripartite protein assembly and a left-handed superhelix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:10148-10152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arents, G., and E. N. Moudrianakis. 1995. The histone fold: a ubiquitous architectural motif utilized in DNA compaction and protein dimerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:11170-11174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aslund, L., L. Carisson, J. Henriksson, M. Rydaker, C. Toro, N. Galanti, and U. Pettersson. 1994. A gene family encoding heterogeneous histone H1 proteins in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 65:317-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Astolfi, F. S., C. Martins de Sa, and E. S. Gander. 1980. On the chromatin structure of Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1:45-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bader, T., and J. Wietzerbin. 1994. Nuclear accumulation of interferon gamma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:11831-11835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baxevanis, A. D., G. Arents, E. N. Moudrianakis, and D. Landsman. 1995. A variety of DNA-binding and multimeric proteins contain the histone fold motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:2685-2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belli, S., A. Formenton, T. Noll, A. Ivens, R. Jacquet, C. Desponds, D. Hofer, and N. Fasel. 1999. Leshmania major histone H1 gene expression from the sw3 locus. Exp. Parasitol. 91:151-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bontempi, E. J., B. M. Porcel, J. Henriksson, L. Carisson, M. Rydaker, E. L. Segura, A. M. Ruiz, and U. Pettersson. 1994. Genes for histone H3 in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 66:147-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown, D. T., B. T. Alexander, and D. B. Sittman. 1996. Differential effect of H1 variant overexpression on cell cycle progression and gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:486-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown, N. H., and F. C. Kafatos. 1988. Functional cDNA libraries from Drosophila embryos. J. Mol. Biol. 203:425-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burley, S. K., X. Xie, K. L. Clark, and F. Shu. 1997. Histone-like transcription factors in eukaryotes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7:94-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Button, L. L., W. R. McMaster. 1988. Molecular cloning of the major surface antigen of Leishmania. J. Exp. Med. 167:724-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang, K.-P. 1983. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of intracellular symbiosis in leishmaniasis. Int. Rev. Cytol. 14(Suppl.):267-305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Church, G. M., and W. Gilbert. 1984. Genomic sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:1991-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coulson, R., V. Connor, J. Chen, and J. W. Ajioka. 1996. Differential expression of Leishmania major β-tubulin genes during acquisition of promastigote infectivity. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 82:227-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Croston, G. E., L. A. Kerrigan, L. M. Lira, D. R. Marshak, and J. T. Kadonaga. 1991. Sequence-specific antirepression of histone H1-mediated inhibition of basal RNA polymerase II transcription. Science 251:643-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cruz, A., C. M. Coburn, and S. M. Beverley. 1991. Double targeted gene replacement for creating null mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:7170-7174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Giorgio, C., O. Ridoux, F. Delmas, N. Azas, M. Gasquet, and P. Timon-David. 2000. Flow cytometric detection of Leishmania parasites in human monocyte-derived macrophages: application to antileishmanial-drug testing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3074-3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dingwall, C., J. Robbins, and S. M. Dilworth. 1989. Characterisation of the nuclear location sequence of Xenopus nucleoplasmin. J. Cell Sci. 11(Suppl.):243-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doenecke, D., W. Albig, H. Bouterfa, and B. Drabent. 1994. Organization and expression of H1 histone and H1 replacement histone genes. J. Cell Biochem. 54:423-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fasel, N. J., D. C. Robyr, J. Mauel, and T. A. Gaser. 1993. Identification of a histone H1-like gene expressed in Leishmania major. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 62:321-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feinberg, A. P., and B. Vogelstein. 1983. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal. Biochem. 132:6-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fong, D., and B. Lee. 1988. Beta tubulin gene of the parasitic protozoan Leishmania mexicana. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 31:97-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galanti, N., M. Galindo, V. Sabaj, I. Espinoza, and G. C. Toro. 1998. Histone genes in trypanosomatids. Parasitol. Today 14:64-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia-Salcedo, J., J. L. Olivier, R. P. Stock, and A. Gonzalez. 1994. Molecular characterization and transcription of the histone H2B gene from the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Microbiol. 13:1033-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Genske, J. E., B. R., Cairns, S. P. Stack, and S. M. Landfear. 1991. Structure and regulation of histone H2B mRNAs from Leishmania enriettii. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:240-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guinet, F., A. Louise, H. Jouin, J. C. Antoine, and C. W. Roth. 2000. Accurate quantitation of Leishmania infection in cultured cells by flow cytometry. Cytometry 39:235-240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hart, D. T., K. Vickerman, and G. H. Coombs. 1981. A quick simple method for purifying Leishmania mexicana amastigotes in large numbers. Parasitology 8:345-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hinterberger, M., I. Pettersson, and J. A. Steiz. 1982. Isolation of small nuclear ribonucleoproteins containing U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6 RNAs. J. Biol. Chem. 258:2604-2613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffmann, A., C.-M. Chiang, T. Oelgeschlager, X. Xie, S. K. Burley, Y. Nakatani, and R. G. Roeder. 1996. A histone octamer-like structure within TFIID. Nature 380:356-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu, C. C., and S. A. Ghabrial. 1995. The conserved, hydrophilic and arginine-rich N-terminal domain of cucumovirus coat proteins contributes to their anomalous electrophoretic mobilities in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels. J. Virol. Methods 55:367-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson, P. J., J. M. Kooter, and P. Borst. 1987. Inactivation of transcription by UV irradiation of T. brucei provides evidence for a multicistronic transcription unit including a VSG gene. Cell 51:273-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kornberg, R. D., and J. O. Thomas. 1974. Chromatin structure; oligomers of the histones. Science 184:865-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McPherson, C. E., E.-Y. Shim, D. S. Friedman, and K. S. Zaret. 1993. An active tissue-specific enhancer and bound transcription factors existing in a precisely positioned nucleosomal array. Cell 75:387-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miloshev, G., P. Venkov, K. van Holde, and J. Zlatanova. 1994. Low levels of exogenous histone H1 in yeast cause cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:11567-11570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muhich, M. L., and J. C. Boothroyd. 1988. Polycistronic transcripts in trypanosomes and their accumulation during heat shock: evidence for a precursor role in mRNA synthesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:3837-3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Myler, P. J., and K. D. Stuart. 2000. Recent developments from the Leishmania genome project. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:412-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nilsen, T. W. 1994. Unusual strategies of gene expression and control in parasites. Science 264:1868-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noll, T. M., C. Desponds, S. I. Belli, T. A. Glaser, and N. J. Fasel. 1997. Histone H1 expression varies during the Leishmania major life cycle. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 84:215-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pelle, R., and N. B. Murphy. 1993. In vivo UV-cross-linking hybridization: a powerful technique for isolating RNA binding proteins. Application to trypanosome mini-exon derived RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:2453-2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Puerta, C., J. Martin, C. Alonso, and M. C. Lopez. 1994. Isolation and characterization of the gene encoding histone H2A from Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 64:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramakrishnan, V., J. Finch, V. M. Grazziano, P. L. Lee, and R. Sweet. 1993. Crystal structure of globular domain of histone H5 and its implications for nucleosome binding. Nature 362:219-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robbins, J., S. M. Dilworth, R. A. Laskey, and C. Dingwall. 1991. Two interdependent basic domains in nucleoplasmin nuclear targeting sequence: identification of a class of bipartite nuclear targeting sequence. Cell 64:615-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schulze, E., S. Nagel, K. Gavenis, and U. Grossbach. 1994. Structurally divergent histone H1 variants in chromosomes containing highly condensed interphase chromatin. J. Cell Biol. 127:1789-1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simpson, L., and D. A. Maslov. 1994. RNA editing and the evolution of parasites. Science 264:1870-1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sogin, M. L., H. J. Elwood, and J. H. Gunderson. 1986. Evolutionary diversity of eukaryotic small-subunit rRNA genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:1383-1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soteriadou, K., A. Tzinia, E. Panou-Pomonis, V. Tsikaris, M. Sakarellos-Daitsiotis, C. Sakarellos, G. Papoulou, and R. Matsas. 1996. Antigenicity and conformational analysis of the Zn(2+)-binding sites of two Zn(2+)-metalloproteases: Leishmania gp63 and mammalian endopeptidase-24.11. Biochem. J. 313:455-466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soteriadou, K. P., M. S. Remoundos, M. C. Katsikas, A. K. Tzinia, V. Tsikaris, C. Sakarellos, and S. J. Tzartos. 1992. The Ser-Arg-Tyr-Asp region of the major surface glycoprotein of Leishmania mimics the Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser cell attachment region of fibronectin. J. Biol. Chem. 267:13980-13985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soteriadou, K. P., A. K. Tzinia, A. Mamalaki, M. Phelouzat, F. Lawrence, and M. Robert-Gero. 1994. Expression of the major surface glycoprotein of Leishmania, gp63, in wild-type and sinefungin-resistant promastigotes. Eur. J. Biochem. 223:61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soto, M., J. M. Requena, L. C. Gomen, I. Navarette, and C. Alonso. 1992. Molecular characterization of a Leishmania donovani infantum antigen identified as histone H2A. Eur. J. Biochem. 205:211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soto, M., J. M. Requena, G. Morales, and C. Alonso. 1994. The Leishmania infantum histone H3 possesses an extremely divergent N-terminal domain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1219:533-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tabassum, R., K. M. Sandman, and J. N. Reeve. 1992. HMt, a histone-related protein from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum delta H. J. Bacteriol. 174:7890-7895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas, F., R. Losa, and A. Klug. 1979. Involvement of histone H1 in the organization of the nucleosome and of the salt-dependent superstructures of chromatin. J. Cell Biol. 83:403-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tzinia, A. K., and K. P. Soteriadou. 1991. Substrate-dependent pH optima of gp63 purified from seven strains of Leishmania. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 47:83-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Voyiatzaki, C. S., and K. P. Soteriadou. 1990. Evidence of transferrin binding sites on the surface of Leishmania promastigotes. J. Biol. Chem. 265:22380-22385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Voyiatzaki, C. S., and K. P. Soteriadou. 1992. Identification and isolation of the Leishmania transferrin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 267:9112-9117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vuorio, T., S. N. Maity, and B. de Combrugghe. 1990. Purification and molecular cloning of the “A” chain of a rat heteromeric CCAAT-binding protein. Sequence identity with the yeast HAP3 transcription factor. J. Biol. Chem. 265:22480-22486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weintraub, H. 1985. Assembly and propagation of repressed and depressed chromosomal states. Cell 42:705-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang, D. M., and F. Y. Liew. 1993. Effects of qinghaosu (artemisinin) and its derivatives on experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. Parasitology 106:7-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zu, X. W., and F. T. Jay. 1991. The E1 functional epitope of the human interferon gamma is a nuclear targeting signal-like element. Mapping of the E1 epitope. J. Biol. Chem. 266:6023-6026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]