Abstract

The intracellular, gram-negative pathogen Brucella abortus establishes chronic infections in host macrophages while downregulating cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). When producing TNF-α, Brucella abortus rough lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activates the same mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways (ERK and JNK) as Escherichia coli LPS, but Brucella LPS is a much less potent agonist.

The intracellular, gram-negative pathogen Brucella abortus establishes chronic infections in host macrophages (20). In such a setting, it is to the pathogen's advantage to trigger as little inflammation as possible and avoid detection by the host's immune system. Infected macrophages secrete the cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) during inflammation. Escherichia coli, which elicits a strong TNF-α response, does not survive for extended periods of time in host macrophages (22). Unlike E. coli, B. abortus does not provoke a robust TNF-α response (5) and is not killed by macrophages. Whether as a strong or weak response, TNF-α can be elicited by whole bacterial cells or by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) purified from enteric bacteria (10).

We undertook the study of B. abortus LPS and the TNF-α it elicits from RAW 264.7 murine macrophage-like cells to compare the inflammatory cell signaling events induced by rough LPS from B. abortus and from E. coli. It has previously been shown that LPS from enteric bacteria, which is structurally distinct from Brucella LPS (2), activates the ERK, JNK, and p38 signaling pathways (6, 21, 23). What is novel in our present work is the finding that B. abortus rough LPS activates the same mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways as E. coli LPS but Brucella LPS is a much less potent agonist. Thus, the less proinflammatory LPS of Brucella may contribute to its ability to survive as a chronic infectious agent in host macrophages.

Deep rough chemotype hexaacyl LPS (ReLPS) from E. coli D31m4 was purified as described by Qureshi et al. (16-18). Methanol-killed B. abortus strain RB51 was provided by Barbara Martin (USDA APHIS Veterinary Services Laboratory, Ames, Iowa). The rough chemotype LPS (from 277 g of dried B. abortus strain RB51) was purified by us by following the procedure of Moreno et al. (14). Rough LPS lacks the O side chain polysaccharide (O antigen), and in the case of B. abortus, the loss of the O side chain correlates with a decrease in virulence in animal hosts (11, 12). While smooth LPS is the norm for most wild-type bacteria, smooth LPS has not yet been thoroughly purified and characterized for many species (8), including Brucella.

The final purity of the rough LPS was determined by both thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. B. abortus LPS (15 μg) was analyzed using TLC as previously described for LPS from other species (7). The untreated LPS chromatographed at the point of origin. When acid hydrolyzed and reanalyzed using TLC, the LPS migrated off the point of origin, as expected of a >95%-pure preparation (7). The LPS preparations purified from B. abortus strain RB51 and E. coli strain D31m4 were essentially protein free, as determined by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and silver staining of 15 μg of LPS (data not shown). One hundred nanograms of RB51 LPS is theoretically equivalent to the amount of LPS from 7 × 107 RB51 cells (see reference 15).

RAW 264.7 murine macrophage-like cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (cell line TIB-71), cultured, and treated as previously described (9). LPS was added to between 1 × 105 and 5 × 105 RAW cells 18 h before the culture supernatant was assayed for TNF-α. Inhibitors U0126 (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.) of the MEK1/2-ERK1/2 pathway (4) and CB506126 and SP600125 (CalBiochem, La Jolla, Calif.) of the p38 (3) and JNK (1) pathways, respectively, were added 30 min prior to the addition of LPS. (The more common p38 kinase inhibitor SB203580 could not be used, because it alone elicited TNF-α production.) TNF-α was assayed by duplicate or triplicate determinations using the murine TNF-α Quantikine M immunoassay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.). Each assay was repeated two or three times.

For Western immunoblotting, cells received a 30-min preincubation with an inhibitor alone or with a subsequent 15-min treatment with LPS. Cells were rinsed once with phosphate-buffered saline, scraped into Harvest buffer (20 mM phosphate-buffered saline [pH 7.3], 50 mM NaF, 1 mM EGTA, 50 μM vanadate, 5 mM benzamidine, 25 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate) on ice, lysed with SDS sample buffer, and disrupted with ultrasonic pulses. Total cellular proteins were separated on 4 to 20% Tris-glycine SDS gels (ISC BioExpress, Kaysville, Utah) and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes with a TransBlot unit (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.). The antibodies used in probing the blots were as follows: pan-JNK and pan-p38 kinase (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, Calif.), pan-ERK (BD Transduction Labs, Lexington, Ky.), and phospho-ERK, -JNK, and -p38 (Promega Corp.). Pan antibodies detect both active and inactive kinase forms. Each Western blotting was repeated twice.

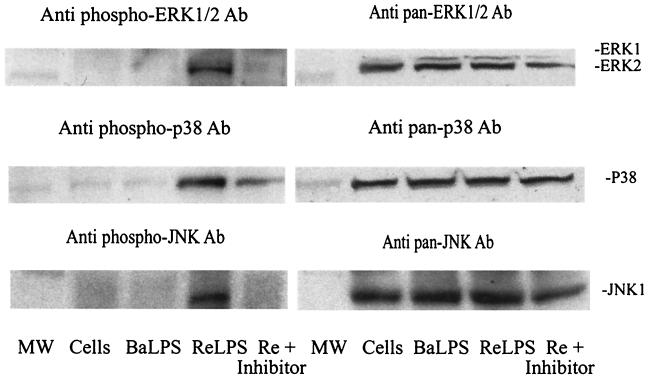

E. coli ReLPS (100 ng/ml) stimulated the MAP kinases (ERK, JNK, and p38) to a much greater extent than B. abortus rough LPS (1 μg/ml), in spite of the 10-fold greater concentration of Brucella LPS (Fig. 1). The effect of the presence of E. coli ReLPS was particularly evident for ERK and p38 when detected by phospho-specific antibodies. That these kinase activations were specific was indicated by the inhibition of phosphorylation after preincubation with small-molecule inhibitors of the respective kinases (Fig. 1, left panels). Pan antibodies indicate equivalent protein loads per lane, and because they detect kinase epitopes distant from the sites of phosphorylation, pan antibody binding is unaffected by the inhibitors of phosphorylation (Fig. 1, right panels). The Western immunoblots shown in Fig. 1 give a qualitative impression of the MAP kinases activated differentially by E. coli and Brucella LPS.

FIG. 1.

Western immunoblots of RAW 264.7 murine macrophage-like cells treated with B. abortus rough LPS (BaLPS) or E. coli LPS (ReLPS) without or with (Re +) 10 μM inhibitor. A total of 1 μg of BaLPS and 100 ng of ReLPS were added per ml. The inhibitors used were U0126 (top panel), CB506126 (middle panel), and SP600125 (bottom panel). The blots shown on the left were probed with phospho-specific antibodies (Ab) against active kinases. The blots shown on the right were probed with pan antibodies that detect both active and inactive kinase forms. The prestained marker (MW) was 50 kDa. The blots were scanned into Adobe Photoshop and assembled with CorelDRAW 9.0.

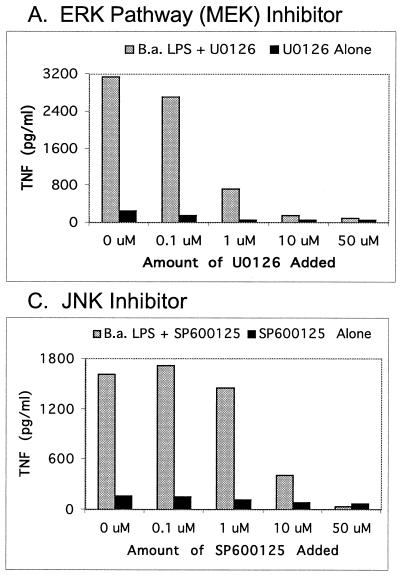

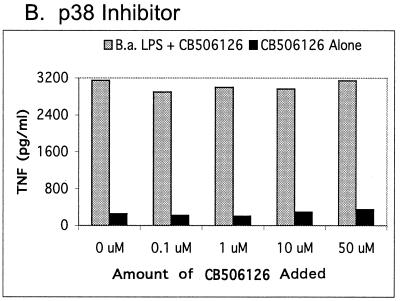

For quantitative analysis of the MAP kinase signaling pathways involved in TNF-α production by Brucella and E. coli LPS, TNF-α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) with and without specific MAP kinase inhibitors were used (Fig. 2 and 3). As shown in Fig. 2, the kinase inhibitors demonstrate a concentration-dependent inhibition of the ERK and JNK pathways. In addition, the inhibitor data indicate that ERK and JNK, but not p38 kinase, were involved in TNF-α signaling. As shown in Fig. 3, an amount of Brucella LPS 2 to 3 orders of magnitude larger than that of E. coli LPS was required to elicit the same amount of TNF-α from RAW cells. This result suggests Brucella LPS is not as potent in stimulating the MAP kinase signaling pathways. As shown in Fig. 3, E. coli and Brucella LPS behave similarly; that is, both elicit TNF-α via the ERK and JNK pathways at three different concentrations of LPS.

FIG. 2.

TNF-α response of RAW 264.7 murine macrophage-like cells to B. abortus (B.a.) rough LPS in the absence or presence of various amounts of kinase inhibitors. Responses to LPS (100 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of the ERK pathway (MEK) inhibitor U0126 (A), the p38 kinase inhibitor CB506126 (B), and the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (C) are shown. The ELISA values shown are the means of duplicate samples from one of two similar experiments.

FIG. 3.

TNF-α response of RAW 264.7 murine macrophage-like cells to various amounts of E. coli ReLPS (A, C, and E) or B. abortus (B.a.) rough LPS (B, D, and F). Responses to various amounts of LPS in the presence or absence of 10 μM ERK pathway (MEK) inhibitor U0126 (A and B), 10 μM p38 kinase inhibitor CB506126 (C and D), and 10 μM JNK inhibitor SP600125 (E and F) are shown. ELISA data points and error bars represent the means and standard deviations, respectively, of assays done in triplicate from a representative experiment.

Previous work has shown that E. coli and Brucella LPS stimulate TNF-α production, but that study did not trace the signaling pathways involved (5). The present report indicates that stimulation of RAW cells by E. coli or Brucella LPS provokes synthesis of TNF-α that is dependent upon posttranslational modification (phosphorylation) of ERK and JNK but not p38 kinase. Others (13) have previously shown that de novo gene expression for JNK but not ERK precedes TNF-α production in RAW cells treated with E. coli LPS. Together, these findings suggest that for LPS to elicit TNF-α in RAW cells, JNK is both synthesized and activated while the existing pool of ERK is converted to the active, phospho form but (apparently) no new ERK message is made (13). In addition, Brucella LPS is 2 to 3 orders of magnitude less potent than E. coli ReLPS in terms of the elicitation of TNF-α from RAW cells.

Our data help explain that an LPS that is less proinflammatory can be a virulence factor by which B. abortus survives as a chronic infectious agent in host macrophages. Qureshi et al. (19) proposed that it is both the greater chain length and the odd number of fatty acids that render B. abortus LPS (C16 to C18 and seven chains) less proinflammatory than E. coli ReLPS (C12 to C14 and six chains).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO1-AI48490 and B.A.R.D. grant US-2968-98C.

Editor: V. J. DiRita

REFERENCES

- 1.Bennett, B. L., D. T. Sasaki, B. W. Murray, E. C. O'Leary, S. T. Sakata, W. Xu, J. C. Leisten, A. Motiwala, S. Pierce, Y. Satoh, S. S. Bhagwat, A. M. Manning, and D. W. Anderson. 2001. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:13681-13686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bundle, D. R., J. W. Cherwonogrodzky, and M. B. Perry. 1987. Structural elucidation of Brucella melitensis M antigen by high-resolution NMR at 500 mHz. Biochemistry 26:8717-8726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.deLaszlo, S. E., et al. 1998. Pyrroles and other heterocycles as inhibitors of p38 kinase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 8:2689-2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Favata, M., K. Y. Horiuchi, E. J. Manos, A. J. Daulerio, D. A. Stradley, W. S. Feeser, D. E. Van Dyk, W. J. Pitts, R. A. Earl, F. Hobbs, R. A. Copeland, R. L. Magolda, P. A. Scherle, and J. M. Trzaskos. 1998. Identification of a novel inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:18623-18632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein, J., T. Hoffman, C. Frasch, E. F. Lizzio, P. R. Beining, D. Hochstein, Y. L. Lee, R. D. Angus, and B. Golding. 1992. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Brucella abortus is less toxic than that from Escherichia coli, suggesting the possible use of B. abortus or LPS from B. abortus as a carrier in vaccines. Infect. Immun. 60:1385-1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han, J., J.-D. Lee, L. Bibbs, and R. J. Ulevitch. 1994. A MAP kinase targeted by endotoxin and hyperosmolarity in mammalian cells. Science 265:808-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirschfeld, M., J. J. Weis, V. Toshchakov, C. A. Salkowski, M. J. Cody, D. C. Ward, N. Qureshi, S. M. Michalek, and S. N. Vogel. 2001. Signaling by Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 agonists results in differential gene expression in murine macrophages. Infect. Immun. 69:1477-1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holst, O. 1999. Chemical structure of the core region of lipopolysaccharides, p. 115-154. In H. Brade et al. (ed.), Endotoxin in health and disease. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 9.Jarvis, B. W., and N. Qureshi. 1997. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced transcription factor Sp1 binding by spectrally pure diphosphoryl lipid A from Rhodobacter sphaeroides, protein kinase inhibitor H-8, and dexamethasone. Infect. Immun. 65:1640-1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lakics, V., A. E. Medvedev, S. Okada, and S. N. Vogel. 2000. Inhibition of LPS-induced cytokines by Bcl-xL in a murine macrophage cell line. J. Immunol. 165:2729-2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madkour, M. M. 2001. Madkour's brucellosis. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 12.McQuiston, J. R., R. Vemulapalli, T. J. Inzana, G. G. Schurig, N. Sriranganathan, D. Fritzinger, T. L. Hadfield, R. A. Warren, N. Snellings, D. Hoover, S. M. Halling, and S. M. Boyle. 1999. Genetic characterization of a Tn5-disrupted glycosyltransferase gene homolog in Brucella abortus and its effect on lipopolysaccharide composition and virulence. Infect. Immun. 67:3830-3835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Means, T. K., R. P. Pavlovich, D. Roca, M. W. Vermeulen, and M. J. Fenton. 2000. Activation of TNF-α transcription utilizes distinct MAP kinase pathways in different macrophage populations. J. Leukoc. Biol. 67:885-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreno, E., M. W. Pitt, L. M. Jones, G. G. Schurig, and D. T. Berman. 1979. Purification and characterization of smooth and rough lipopolysaccharides from Brucella abortus. J. Bacteriol. 138:361-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neidhardt, F. C., J. L. Ingraham, and M. Schaechter. 1990. Physiology of the bacterial cell, p. 4. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, Mass.

- 16.Qureshi, N., J. P. Honovich, H. Hara, R. J. Cotter, and K. Takayama. 1988. Location of fatty acids in lipid A obtained from lipopolysaccharide of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides ATCC 17023. J. Biol. Chem. 263:5502-5504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qureshi, N., K. Takayama, D. Heller, and C. Fenselau. 1983. Position of ester groups in the lipid A backbone of lipopolysaccharides obtained from Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 258:12947-12951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qureshi, N., K. Takayama, P. Mascagni, J. Honovich, R. Wong, and R. J. Cotter. 1988. Complete structural determination of lipopolysaccharide obtained from deep rough mutant of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 263:11971-11976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qureshi, N., K. Takayama, U. Seydel, R. Wang, R. J. Cotter, P. K. Agrawal, C. A. Bush, R. Kurtz, and D. T. Berman. 1994. Structural analysis of lipid A derived from the lipopolysaccharide of Brucella abortus. J. Endotoxin Res. 1:137-148. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rittig, M. G., M.-T. Alvarez-Martinez, F. Porte, J.-P. Liautard, and B. Rouot. 2001. Intracellular survival of Brucella spp. in human monocytes involves conventional uptake but special phagosomes. Infect. Immun. 69:3995-4006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swantek, J. L., M. H. Cobb, and T. D. Geppert. 1997. Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase (JNK/SAPK) is required for lipopolysaccharide stimulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) translation: glucocorticoids inhibit TNF-α translation by blocking JNK/SAPK. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6274-6282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takayama, K., N. Qureshi, B. Beutler, and T. N. Kirkland. 1989. Diphosphoryl lipid A from Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides ATCC 17023 blocks induction of cachectin in macrophages by lipopolysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 57:1336-1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinstein, S. L., J. S. Sanghera, K. Lemke, A. L. DeFranco, and S. L. Pelech. 1992. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide induces tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 267:14955-14962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]