Abstract

The role of glycosylinositol phospholipid 1 (GIPL-1) of Leishmania (Leishmania) major in the interaction of promastigotes and amastigotes with macrophages was analyzed. Monoclonal antibody MEST-1, which recognizes glycolipids containing terminal galactofuranose (Galf) residues (E. Suzuki, M. S. Toledo, H. K. Takahashi, and A. H. Straus, Glycobiology 7:463-468, 1997), was used to detect GIPL-1 in Leishmania by indirect immunofluorescence and to analyze its role in macrophage infectivity. L. major promastigotes showed intense fluorescence with MEST-1, and GIPL-1 was detected in both amastigote and promastigote forms by high-performance thin-layer chromatography immunostaining by using MEST-1. Delipidation of L. major promastigotes with isopropanol-hexane-water eliminated the MEST-1 reactivity, confirming that only GIPL-1 is recognized in either amastigotes or promastigotes of this species. The biological role of GIPL-1 in the ability of L. major to invade macrophages was studied by using either Fab fragments of MEST-1 or methylglycosides. Preincubation of parasites with Fab fragments reduced macrophage infectivity in about 80% of the promastigotes and 30% of the amastigotes. Preincubation of peritoneal macrophages with p-nitrophenyl-β-galactofuranoside (10 mM) led to significant (∼80%) inhibition of promastigote infectivity. These data suggest that a putative new receptor recognizing β-d-Galf is associated with L. major macrophage infectivity and that GIPL-1 containing a terminal Galf residue is involved in the L. major-macrophage interaction.

Leishmania (Leishmania) major is the causative agent of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis. It is an intracellular parasite, and macrophages are its primary target host cells. The parasite-macrophage interaction is a multistep phenomenon, which has been shown to be mediated mainly by the protease gp63 and lipophosphoglycan (LPG) (2, 3, 9, 10, 20, 28, 31). Our studies of the biological roles of glycolipid antigens present on the parasite surface have demonstrated that Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis amastigote stage-specific glycosphingolipid antigens containing terminal Galβ1-3Gal are also related to macrophage invasion (23). A number of studies have identified macrophage receptors involved in entry of Leishmania into cells, including mannose-fucose receptor (33), receptors for advanced glycosylation end products (17), fibronectin (2), complement receptor (CR1 and CR3) (4, 7, 20, 28, 32, 33), and Fc receptor (8).

We analyzed the role of glycosylinositol phospholipid 1 (GIPL-1) of L. major and its galactofuranose (Galf) residue in the interactions of L. major promastigotes and amastigotes with mouse peritoneal macrophages.

Glycoconjugates containing Galf residues have been found in various microorganisms, including trypanosomatids, fungi, and bacteria (1, 5, 6, 11, 12, 14, 18, 26, 29). In Leishmania, Galf can be present as a nonterminal residue, as it is in LPG, the main surface glycoconjugate of promastigotes (31), and in GIPL-2 and GIPL-3 of L. major (14) and as a terminal residue in GIPL-1 of L. major (14). Although the biological role of Galf residues is not known, one intriguing hypothesis is that terminal Galf residues play a central role in the survival of fungi and parasites by blocking action of the host's glycosidases against glycoconjugates of the fungi and parasites. On the other hand, Galf may function as a strong immunogen. The absence of Galf and galactofuranosidases in mammalian host cells makes these molecules potentially useful as specific targets for therapy of parasitic and fungal diseases.

In order to analyze the role of terminal Galf residues in L. major, monoclonal antibody (MAb) MEST-1, which recognizes glycolipids containing terminal Galf residues linked β-1-3 or β-1-6 to mannose (26, 27), was used to detect GIPL-1 in Leishmania cells and to analyze its relationship with macrophage infectivity of L. major. MEST-1 reactivity with L. major was analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence analysis and by high-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) immunostaining of glycolipid fractions. The role of L. major Galf residues in macrophage infectivity was studied by using either MEST-1 or p-nitrophenyl-glycoside as an inhibitor in macrophage infection assays.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites.

Promastigotes of L. major MRHO/SU/1959/P were kindly provided by A. Cruz, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil. Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis MHOM/BR/1987/M11272 was isolated from patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis at Laboratório de Ensino e Pesquisa em Análises Clínicas, Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Maringá, Brazil. L. amazonensis MHOM/BR/1973/M2269 and Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi MHOM/BR/1972/LD were kindly provided by C. L. Barbiéri, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. Promastigotes were cultured at 23°C in medium 199 supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Cultilab).

Solid-phase RIA of parasites.

Promastigotes of various Leishmania species were adsorbed on 96-well plates precoated with 0.1% poly-l-lysine (molecular weight, 500,000) for 30 min as described by McMahon-Pratt et al. (16). Promastigotes (1 × 106 parasites/well or 2 × 106 parasites in the first well and double-diluted preparations in subsequent wells) were added, the plates were centrifuged for 10 min at 800 × g, and the parasites were fixed for 15 min with 0.5% glutaraldehyde in cold 0.01 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 0.15 M NaCl (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]). The plates were washed with PBS, and unbound aldehyde groups were blocked by adding 0.1 M glycine (pH 8.0) and incubating the preparations for 30 min. Fixed parasites were delipidated by using isopropanol-hexane-water (IHW) (55:20:25, vol/vol/vol; upper phase discarded) as described by Suzuki et al. (26). The plates were washed with PBS, blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS (200 μl) for 2 h, and incubated for 2 h with an MAb for a solid-phase radioimmunoassay (RIA). The amount of MAb bound was determined by reaction with rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (50 μl). The plates were washed three times with PBS, and 50 μl of 125I-labeled protein A (105 cpm) in 1% BSA was added to each well; then the plates were incubated for 1 h and washed five times with PBS. The radioactivity in each well was measured with a gamma counter (24).

Preparation of amastigotes.

Promastigotes from the stationary culture phase (2 × 107 parasites) were inoculated into Golden hamster footpads. After 5 to 6 weeks, lesions were surgically removed, and the tissue was minced. Debris was eliminated by Nitex nylon filtration (pore size, 80 μm; Tetko, Monterey Park, Calif.). Infected macrophages were homogenized (20 strokes), and the cell suspension was centrifuged at 1,300 × g for 10 min. To lyse erythrocytes, the pellet was resuspended in an ammonium chloride solution (8.29 g of NH4Cl per liter, 1 g of KHCO3 per liter, 37.2 mg of EDTA per liter), incubated for 10 min, and centrifuged at 1,300 × g, and the pellet containing amastigotes was washed three times with PBS by centrifugation at 1,800 × g. Parasites obtained in this way were used for a macrophage infection assay and for glycolipid purification. All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee.

Glycolipid extraction.

Amastigotes (1 × 108 cells) and promastigotes (1 × 1010 cells) were extracted three times with chloroform-methanol-water (4:8:3), and the extracts were combined and dried in a rotary evaporator. The dried residue was dissolved in chloroform-methanol (95:5) and applied to a Silica Gel 60 column (1 by 15 cm), and the glycolipids were eluted by increasing the concentration of methanol (chloroform/methanol ratios, 95:5, 90:10, 70:30, 60:40, and 10:90). Fractions were dried under a stream of N2 at 37°C, resuspended in chloroform-methanol (2:1), and analyzed by HPTLC.

HPTLC immunostaining.

Glycolipids present in fractions obtained from chromatography as described above were detected by HPTLC by using chloroform-methanol-0.02% CaCl2 (60:40:9). Immunostaining was performed by the procedure of Magnani et al. (13). After HPTLC development, the plates were dried and soaked in 0.5% polymethacrylate in hexane, dried, blocked for 2 h with 1% BSA in PBS, incubated with MAb MEST-1 overnight, and incubated sequentially with rabbit anti-mouse IgG and 125I-labeled protein A (4 × 105 cpm/ml) (25).

Preparation of peritoneal macrophages.

Peritoneal macrophages were harvested by washing the peritoneal cavities of BALB/c mice with PBS. The macrophages were washed three times with cold PBS by centrifugation at 450 × g, and the final pellet was resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 10 mM HEPES, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. Macrophages (5 × 105 cells) were placed on 13-mm-diameter sterile glass coverslips in 24-well plates. Nonadherent cells were removed by several washes with RPMI 1640 medium, and the plates were kept at 37°C in a CO2 incubator (23).

Inhibition of Leishmania infectivity in macrophages by MAbs.

Amastigotes and promastigotes (5 × 106 cells/150 μl) were preincubated with different concentrations of Fab fragments (0.03 to 2.5 μg) as indicated below. After 1 h the parasites were washed with RPMI 1640 medium and incubated with peritoneal macrophages (10 promastigotes/macrophage and 5 × 106 parasites/well or 3 amastigotes/macrophage and 1.5 × 106 parasites/well) for 2 h in RPMI 1640 medium without serum at 37°C. Nonadherent parasites were removed by washing monolayers with medium. Infected macrophages were kept in RPMI 1640 medium with 5% fetal calf serum in a CO2 incubator for 24 h. The macrophages were fixed with methanol and stained with Giemsa solution. The phagocytic index was determined by multiplying the percentage of macrophages that phagocytosed at least one parasite by the average number of parasites per infected macrophage (300 cells were examined) as described by Silveira et al. (22). Inhibition was expressed as the percentage of phagocytosis obtained with each MAb compared with the control (Fab fragment of an irrelevant IgG3 MAb).

Inhibition of Leishmania infectivity in macrophages by glycosides.

Twenty-four-well plates containing 5 × 105 macrophages/well were preincubated at room temperature with 0.5-ml portions of various p-nitrophenyl-glycosides (10 mM), including p-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactofuranoside, p-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside, p-nitrophenyl-α-d-galactopyranoside, and p-nitrophenyl-α-d-mannopyranoside (Sigma). After 1 h, 5 × 106 promastigotes in 0.3 ml of RPMI 1640 medium without serum were added to peritoneal macrophages (10 parasites/macrophage), and the preparations were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Nonadherent parasites were removed by washing the monolayers with RPMI 1640 medium. Infected macrophages were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium with 5% fetal calf serum in a CO2 incubator for 24 h. Macrophages were fixed with methanol and analyzed as described above.

Effect of p-nitrophenyl-glycosides on L. major growth.

Promastigotes (2 × 107 cells) were resuspended in 1.2 ml of RPMI 1640 medium and preincubated with 1.2-ml portions of solutions of various p-nitrophenyl-glycosides as described above (10 mM) for 2 h at 37°C. The suspensions were centrifuged, and the parasites were washed once with medium 199. The parasites were resuspended in 5 ml of medium 199 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and kept at 23°C. The number of parasites was determined every 24 h.

Indirect immunofluorescence.

Parasites (1 × 108 cells) were fixed with 1% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min. The cells were washed and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS, and 20-μl portions of the suspension were added to coverslips. Air-dried preparations were delipidated with an IHW mixture, as described by Suzuki et al. (26). The plates were then washed with PBS, flooded for 1 h with PBS containing 5% BSA, and incubated sequentially with MAb culture supernatant for 1 h and with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG for 1 h. After each incubation, the coverslips were washed five times with PBS and examined with an epifluorescence microscope. An irrelevant IgG3 MAb was used for control experiments. Alternatively, immunofluorescence of delipidated parasites was examined with sera from BALB/c mice infected with L. major.

RESULTS

Reactivity of MEST-1 with Leishmania promastigotes.

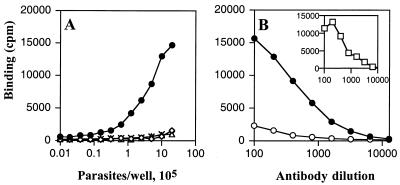

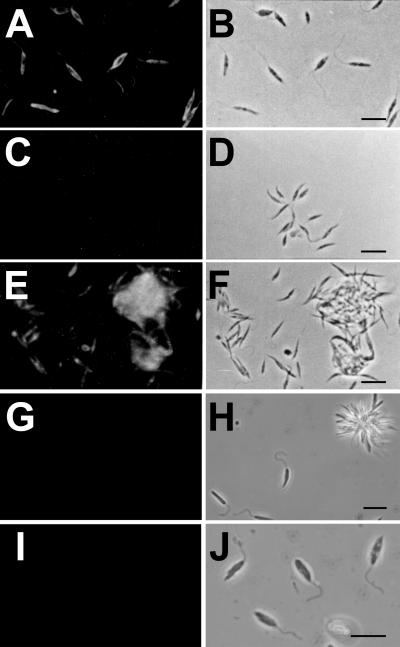

Of the cells of Leishmania species analyzed by solid-phase RIA, only L. major promastigotes were reactive with MAb MEST-1 (Fig. 1A). MEST-1 reactivity was completely absent after parasite delipidation with IHW (Fig. 1B). The reactive antigen was recovered in the organic extract, as shown in Fig. 1. These results were confirmed by indirect immunofluorescence. Strong fluorescence was observed on the whole surface of promastigotes (Fig. 2A), indicating that the antigen is present on the parasite surface. When fixed parasites were delipidated, no reactivity with MEST-1 was observed (Fig. 2C); however, the delipidated parasites were still recognized by sera of L. major-infected BALB/c mice (Fig. 2E). These results indicate that MEST-1 recognizes an epitope present only in the lipid fraction. No reactivity with MEST-1 was observed with Leishmania species which do not express GIPL-1, such as L. amazonensis and L. braziliensis, as shown in Fig. 2G and I, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Reactivity of MAb MEST-1 with promastigotes of Leishmania spp. by solid-phase RIA. (A) Preparation containing 2 × 106 parasites that was serially diluted, adsorbed onto 96-well plates, and incubated with MEST-1. Symbols: •, L. major; ◊, L. braziliensis; ▵, L. chagasi; ×, L. amazonensis. (B) Preparation containing 1 × 106 L. major promastigotes adsorbed onto 96-well plates that was delipidated (○) or not delipidatd (•) with IHW (55:20:25) and incubated with MEST-1, as described in Materials and Methods. (Inset) MEST-1 reactivity with IHW fraction removed from wells and adsorbed on a new 96-well plate.

FIG. 2.

MEST-1 reactivity with Leishmania promastigotes as determined by indirect immunofluorescence. (A and B) L. major promastigotes incubated with MEST-1; (C and D) L. major promastigotes treated with IHW (55:20:25) and incubated with MEST-1; (E and F) L. major promastigotes treated with IHW (55:20:25) and incubated with serum from BALB/c mice infected with L. major; (G and H) L. amazonensis promastigotes incubated with MEST-1; (I and J) L. braziliensis promastigotes incubated with MEST-1. (A, C, E, G, and I) Fluorescence microscopy. (B, D, F, H, and J) Phase-contrast microscopy. Bars = 20 μm.

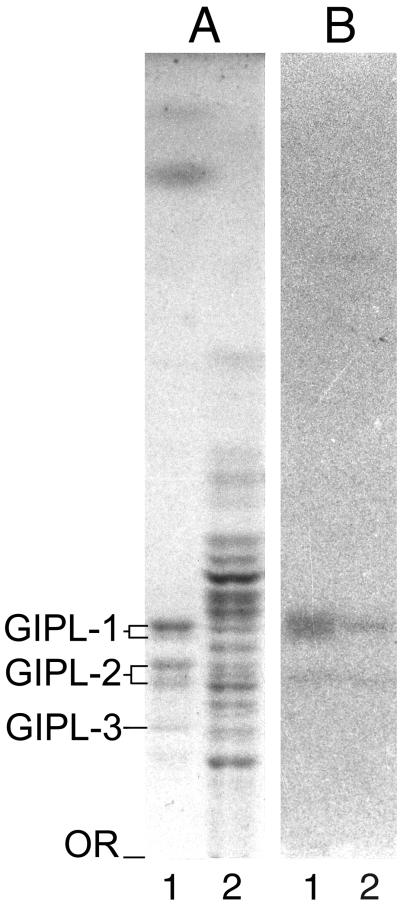

HPTLC immunostaining of glycolipid fraction of L. major with MEST-1.

Glycolipid fractions purified from promastigote and amastigote forms of L. major were analyzed by HPTLC, stained with orcinol-H2SO4 (Fig. 3A), and immunostained with MEST-1 (Fig. 3B). HPTLC analysis revealed the presence GIPL-1, GIPL-2, and GIPL-3 in promastigotes (Fig. 3A, lane 1), but a larger number of glycolipid components was observed in amastigotes (Fig. 3A, lane 2). Both parasite forms present GIPL-1 as the main antigen reactive with MEST-1, as shown by HPTLC immunostaining. In amastigotes, the two bands that were reactive with MEST-1 corresponded to GIPL-1 and its lyso-alkyl-phosphatidylinositol derivative (the lower band), confirming previous findings that larger amounts of lyso-alkyl-phosphatidylinositol are present in L. major amastigotes than in promastigotes (19, 21).

FIG. 3.

HPTLC pattern of glycolipids from L. major. Glycolipid fractions were applied to an HPTLC plate and developed in chloroform-methanol-0.02% CaCl2 (60:40:9). (A) Staining with orcinol-H2SO4; (B) immunostaining with MEST-1. Lanes 1, glycolipids from promastigotes; lanes 2, glycolipids from amastigotes. OR, origin.

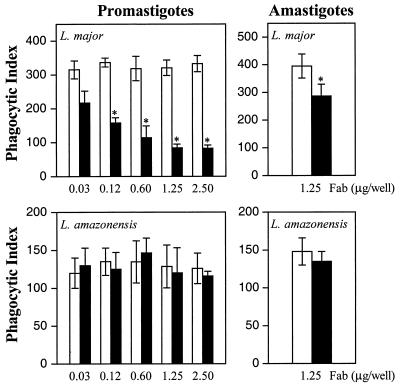

Effect of Fab fragments on Leishmania infectivity.

To test whether the antigens recognized by MAb MEST-1 are involved in Leishmania-macrophage interactions, we performed in vitro assays to determine the capacity of Leishmania to invade macrophage monolayers in the presence of MEST-1 and an irrelevant IgG MAb. Promastigotes were preincubated at room temperature with different concentrations of purified Fab fragments, and macrophage infectivity was analyzed. Fab fragments were used to prevent opsonization of parasites by the macrophage Fc receptor. Fab fragments of MEST-1 reduced the phagocytic index of L. major up to 80% for promastigotes and 30% for amastigotes (Fig. 4, upper panels). On the other hand, as expected, no effect of MEST-1 was detected when L. amazonensis was preincubated with the same concentrations of Fab fragments (Fig. 4, lower panels), since this parasite does not express GIPL-1.

FIG. 4.

Macrophage phagocytic indices for L. major (upper panels) and L. amazonensis (lower panels) preincubated with Fab fragments of MAbs. Fab fragments of MEST-1 (solid bars) or CU-1 (open bars) at different concentrations were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with L. major and L. amazonensis. Next, parasites were incubated with macrophages (10 promastigotes per macrophage or three amastigotes per macrophage) for 2 h at 37°C. Nonadherent parasites were removed by washing monolayers with culture medium. Infected macrophages were kept in a CO2 incubator for 24 h. Monolayers were washed with PBS, fixed with methanol, and stained with Giemsa stain. The phagocytic index (ordinate) was determined by multiplying the percentage of infected macrophages by the average number of parasites per infected macrophage (300 cells were examined). In control experiments, parasites were preincubated with Fab fragments of an irrelevant MAb (anti-Tn antigen CU-1). The values are means ± standard deviations from triplicate experiments. An asterisk indicates that a value is significantly different from the control value, as calculated by Student's t test (P < 0.01).

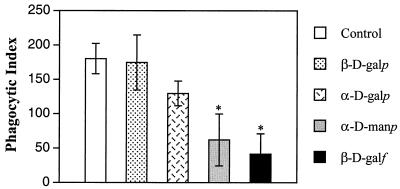

Effect of glycosides on Leishmania macrophage infectivity.

In order to determine the role of the Galf residue in L. major macrophage infectivity, peritoneal macrophages were preincubated with various p-nitrophenyl-glycosides (10 mM) and infected with promastigotes. No effect on the infectivity was observed when macrophages were incubated with p-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside. Conversely, significant levels of inhibition of infectivity by p-nitrophenyl-α-d-mannopyranoside (∼65%) and p-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactofuranoside (∼77%) were observed (Fig. 5). On the other hand, when L. amazonensis promastigote forms were used in the infection assay, p-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactofuranoside did not affect the parasite infectivity (data not shown). In order to demonstrate that the inhibitory effect was not due to a glycoside effect on L. major viability, parasites were cultivated in the presence of glycosides, and no difference in growth rates was observed for up to 8 days of culture (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Effects of p-nitrophenyl-glycosides on L. major macrophage infectivity. Preparations containing 5 × 105 macrophages were preincubated with four p-nitrophenyl-glycosides (10 mM) for 1 h at room temperature. Next, 5 × 106 promastigotes were incubated with macrophages for 2 h at 37°C. Nonadherent parasites were removed by washing the monolayers with culture medium. Infected macrophages were kept in a CO2 incubator for 24 h. In control experiments, parasites were preincubated in the absence of p-nitrophenyl-glycoside. The values are means ± standard deviations from triplicate experiments. An asterisk indicates that a value is significantly different from the control value, as calculated by Student's t test (P < 0.01). β-d-galp, p-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside; α-d-galp, p-nitrophenyl-α-d-galactopyranoside; α-d-manp, p-nitrophenyl-α-d-mannopyranoside; β-d-galf, p-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactofuranoside.

DISCUSSION

In solid-phase RIA and indirect immunofluorescence studies, MEST-1 showed high reactivity with L. major but no reactivity with L. braziliensis, L. chagasi, or L. amazonensis, confirming that GIPL-1 is expressed in L. major but not in the other Leishmania species. As expected, LPG, the main surface glycoconjugate of Leishmania sp. promastigotes, was not detected by MEST-1, which recognizes only terminal Galf residues (present in GIPL-1), not internal Galf residues (present in LPG, GIPL-2, and GIPL-3).

In indirect immunofluorescence studies, L. major promastigotes showed intense fluorescence with MEST-1. Amastigotes showed a lower degree of fluorescence (data not shown). Treatment of promastigotes with IHW eliminated reactivity with MEST-1, and the reactive material was recovered in the organic fraction, indicating its lipid nature. HPTLC of organic extracts confirmed that both amastigotes and promastigotes presented GIPL-1 as the antigen recognized by MEST-1.

According to McConville and Bacic (15) L. major promastigotes and amastigotes present about 10 × 106 and 4 × 106 molecules of GIPLs/cell, respectively. By performing densitometry with HPTLC plates containing glycolipids of promastigotes (as shown in Fig. 3A), it was determined that GIPL-1 accounts for about 40% of the total GIPLs, which corresponds to about 1.6 × 106 molecules/cell. On the other hand, it was not possible to quantify the GIPL-1 in amastigotes due to the small number of parasites in the hamster lesions, and consequently, it was not possible to determine with accuracy the concentration of GIPL-1 in a mixture that also contained glycolipids from hamster lesions. Nevertheless, it is known that GIPL-1 accounts for 36% of the total GIPLs of LV 39 amastigotes isolated from nude mice lesions, as described by Schneider et al. (21).

The role of GIPL-1 and its Galf residue in the binding and invasion of macrophage monolayers was analyzed by preincubating parasites with MEST-1 Fab fragments, which reduced macrophage infectivity by ∼80% for promastigotes and 30% for amastigotes. The more modest inhibition of amastigote adhesion than of promastigote adhesion could have been due to GIPL-1 crypticity in amastigotes or due to a lower GIPL-1 concentration in amastigotes than in promastigotes, as observed by immunofluorescence, which detected weaker MEST-1 reactivity with amastigotes than with promastigotes. The substantial inhibition (∼80%) of macrophage infection by promastigotes in the presence of p-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactofuranoside confirmed the importance of the Galf residue. Significant inhibition (∼65%) of macrophage infection was also observed when p-nitrophenyl-α-d-mannopyranoside was used, indicating that a mannose receptor is involved in the Leishmania-macrophage interaction. No inhibition was observed when macrophages were preincubated with p-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside. These findings indicate that the galactose receptor present in macrophages associated with L. major infectivity does not recognize isolated galactose residues but requires ligands with a more complex structure. This is consistent with the conclusion of Kelleher et al. (10), who reported that L. major promastigote binding to macrophages requires a minimum structure defined as PO4-6[Gal(β1-3)Gal(β1-3)Gal(β1-3)]Galβ1-4Man(α1-), which is present in LPG.

Cell-cell interactions and attachment processes are multistep phenomena, and the present results indicate that one such receptor recognizes terminal Galf residues. The receptor for terminal Galf residues in glycoconjugates of parasites and fungi has not been characterized yet, but it is currently being investigated. Tsuji et al. (30) recently identified a new type of human lectin, termed human intelectin, which binds to pentoses and to d-Galf residues in the presence of Ca2+. A recombinant human intelectin recognizes bacterial arabinogalactan of Nocardia containing d-Galf; thus, this lectin may be involved in recognition of various pathogens containing Galf residues (e.g., Nocardia, Mycobacterium, Streptococcus, Leishmania, and Trypanosoma species). The present results suggest that terminal residues of β-d-Galf present in GIPL-1 from either promastigote or amastigote forms of L. major are recognized by a previously undescribed macrophage receptor involved in the Leishmania-macrophage interaction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by FAPESP, CNPq, and PRONEX.

We thank Stephen Anderson for editing the manuscript.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acosta-Serrano, A., S. Schenkman, N. Yoshida, A. Mehlert, J. M. Richardson, and M. A. J. Ferguson. 1995. The lipid structure of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored mucin-like sialic acid acceptors of Trypanosoma cruzi changes during parasite differentiation from epimastigote to infective metacyclic trypomastigote forms. J. Biol. Chem. 270:27244-27253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brittingham, A., G. Chen, B. S. McGwire, K.-P. Chang, and D. M. Mosser. 1999. Interaction of Leishmania gp63 with cellular receptors for fibronectin. Infect. Immun. 67:4477-4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang, K. P., and M. Chaudhuri. 1990. Molecular determinants of Leishmania virulence. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 44:499-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper, A., H. Rosen, and J. M. Blackwell. 1988. Monoclonal antibodies that recognize distinct epitopes of the macrophage type three complement receptor differ in their ability to inhibit binding of Leishmania promastigotes harvested at different phases of their growth cycle. Immunology 65:511-514. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daffe, M., M. McNeil, and P. J. Brennan. 1993. Major structural features of the cell wall arabinogalactans of Mycobacterium, Rhodococcus, and Nocardia spp. Carbohydr. Res. 249:383-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daffé, M., P. J. Brennan, and M. McNeil. 1990. Predominant structural features of the cell wall arabinogalactan of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as revealed through characterization of oligoglycosyl alditol fragments by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry and by 1H and 13C NMR analyses. J. Biol. Chem. 265:6734-6743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Da Silva, R. P., B. F. Hall, K. A. Joiner, and D. L. Sacks. 1989. CR1, the C3b receptor, mediates binding of infective Leishmania major metacyclic promastigotes to human macrophages. J. Immunol. 143:617-622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guy, R. A., and M. Belosevic. 1993. Comparison of receptors required for entry of Leishmania major amastigotes into macrophage. Infect. Immun. 61:1553-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelleher, M., S. F. Moody, P. Mirabile, A. H. Osborn, A. Bacic, and E. Handman. 1995. Lipophosphoglycan blocks attachment of Leishmania major amastigotes to macrophages. Infect. Immun. 63:43-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelleher, M., A. Bacic, and E. Handman. 1992. Identification of a macrophage binding determinant on lipophosphoglycan from Leishmania major. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lederkremer, R. M., and W. Colli. 1995. Galactofuranose-containing glycoconjugates in trypanosomatids. Glicobiology 5:547-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levery, S. B., M. S. Toledo, A. H. Straus, and H. K. Takahashi. 1998. Structure elucidation of sphingolipids from the mycopathogen Paracoccidioides brasiliensis: an immunodominant β-galactofuranose residue is carried by a novel glycosylinositol phosphoceramide antigen. Biochemistry 37:8764-8775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnani, J. L., D. F. Smith, and V. Ginsburg. 1990. Detection of gangliosides that bind toxin: direct binding of 125I-labeled toxin to thin-layer chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 109:399-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McConville, M. J., and M. A. J. Ferguson. 1993. The structure, biosynthesis and function of glycosylated phosphatidylinositols in the parasitic protozoa and higher eukaryotes. Biochem. J. 294:305-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McConville, M. J., and A. Bacic. 1990. The glycoinositolphospholipid profiles of two Leishmania major strains that differ in lipophosphoglycan expression. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 38:57-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMahon-Pratt, D., C. L. Jaffe, and G. Grimaldi. 1984. Application of monoclonal antibodies to the classification of Leishmania species, p. 133. In C. M. Morel (ed.), Genes and antigens of parasites. A laboratory manual. Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- 17.Mosser, D. M., H. Vlassar, P. J. Edelson, and A. Cerami. 1987. Leishmania promastigotes are recognized by the macrophage receptor for advanced glycosylation end products. J. Exp. Med. 165:140-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Previato, J. O., P. A. J. Gorin, M. Mazurek, M. T. Xavier, B. Fournet, J. M. Wieruszesk, and L. Mendonça-Previato. 1990. Primary structure of the oligosaccharide chain of lipopeptidophosphoglycan of epimastigote forms of Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Biol. Chem. 265:2518-2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Proudfoot, L., P. Schneider, M. A. J. Ferguson, and M. J. McConville. 1995. Biosynthesis of the glycolipid anchor of lipophosphoglycan and the structurally related glycoinositolphospholipids from Leishmania major. Biochem. J. 308:45-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russell, D. G., and S. D. Wright. 1988. Complement receptor type 3 (CR3) binds to an Arg-Gly-Asp-containing region of the major surface glycoprotein, gp63, of Leishmania promastigotes. J. Exp. Med. 168:279-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider, P., J.-P. Rosat, A. Ransijn, M. A. J. Ferguson, and M. J. McConville. 1993. Characterization of glycoinositol phospholipids in the amastigote stage of the protozoan parasite Leishmania major. Biochem. J. 295:555-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silveira, T. G. V., E. Suzuki, H. K. Takahashi, and A. H. Straus. 2001. Inhibition of macrophage invasion by monoclonal antibodies specific to Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis promastigotes and characterisation of their antigens. Int. J. Parasitol. 31:1451-1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Straus, A. H., S. B. Levery, M. G. Jasiulionis, M. E. K. Salyan, S. J. Steele, L. R. Travassos, S. Hakomori, and H. K. Takahashi. 1993. Stage-specific glycosphingolipids from amastigote forms of Leishmania (L.) amazonensis. J. Biol. Chem. 268:13723-13730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Straus, A. H., L. R. Travassos, and H. K. Takahashi. 1992. A monoclonal antibody (ST-1) directed to native heparin chain. Anal. Biochem. 201:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Straus, A. H., E. Suzuki, M. S. Toledo, C. M. Takizawa, and H. K. Takahashi. 1995. Immunochemical characterization of carbohydrate antigens from fungi, protozoa and mammal by monoclonal antibodies directed to glycan epitope. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 28:919-923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki, E., R. A. Mortara, H. K. Takahashi, and A. H. Straus. 2001. Reactivity of MEST-1 (anti-galactofuranose) with Trypanosoma cruzi glycosylinositol phosphorylceramides (GIPCs). Immunolocalization of GIPCs in acidid vesicles of epimastigotes. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8:1031-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki, E., M. S. Toledo, H. K. Takahashi, and A. H. Straus. 1997. A monoclonal antibody directed to terminal residue of β-galactofuranose of a glycolipid antigen isolated from Paracoccidioides brasiliensis: cross-reactivity with Leishmania major and Trypanosoma cruzi. Glycobiology 7:463-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Talamás-Rohana, P., S. D. Wright, M. R. Lennartz, and D. G. Russel. 1990. Lipophosphoglycan from Leishmania mexicana promastigotes binds to members of the CR3, p150,95 and LFA family of leukocyte integrins. J. Immunol. 144:4817-4824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toledo, M. S., E. Suzuki, A. H. Straus, and H. K. Takahashi. 1995. Glycolipids from Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. Isolation of a galactofuranose-containing glycolipid reactive with sera of patients with paracoccidioidomycosis. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 33:47-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsuji, S., J. Uehori, M. Matsumoto, Y. Suzuki, A. Matsuhisa, K. Toyoshima, and T. Seya. 2001. Human intelectin is a novel soluble lectin that recognizes galactofuranose in carbohydrate chains of bacterial wall. J. Biol. Chem. 276:23456-23463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turco, S. J., and A. Descoteaux. 1992. The lipophosphoglycan of Leishmania parasites. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 46:65-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Strijp, J. A. G., D. G. Russell, E. Toumanen, E. J. Brown, and S. D. Wright. 1993. Ligand specificity of purified complement receptor type three (CD11b/CD18, alpha m beta 2, Mac-1). Indirect effects of an Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) sequence. J. Immunol. 151:3324-3356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson, M. E., and R. D. Pearson. 1988. Roles of CR3 and mannose receptors in the attachment and ingestion of Leishmania donovani by human mononuclear phagocytes. Infect. Immun. 56:363-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]