Abstract

The human neutrophil-derived cationic protein CAP37, also known as azurocidin or heparin-binding protein, enhances the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced release of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in isolated human monocytes. We measured the release of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-8 (IL-8) in human whole blood and found that in addition to CAP37, other arginine-rich cationic polypeptides, such as the small structurally related protamines, enhance LPS-induced monocyte activation. As CAP37 and protamines share high levels of arginine content, we tested different synthetic poly-l-amino acids and found that poly-l-arginine, and to a lesser extent poly-l-lysine, increased IL-8 production in LPS-stimulated human whole blood. Protamine-enhanced LPS responses remained unaffected by the presence of free l-arginine or l-lysine, indicating that basic polypeptides but not basic amino acids act synergistically with LPS. In agreement with observations previously reported for CAP37, the LPS-enhancing effect of poly-l-arginine was completely abolished upon antibody blockade of the human LPS receptor, CD14. Protamines, either immobilized or in solution, bound LPS specifically. Poly-l-arginines, protamines, and CAP37 were equally effective in inhibiting binding of LPS to immobilized l-arginines. Taken together, our results suggest a CD14-dependent mechanism by which arginine-rich cationic proteins modulate LPS-induced monocyte activation and support the prediction that other strongly basic proteins could act as amplifiers of LPS responses.

In human plasma, gram-negative endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide [LPS]) rapidly forms a high-affinity complex with LPS-binding protein (LBP) (32). The resulting LPS-LBP complex is recognized by the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored monocyte differentiation antigen CD14 (16, 38). Signal transduction occurs via association of CD14 with Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (23). TLR4 activates a signaling pathway similar to but not identical to the interleukin-1 (IL-1) pathway, resulting in the production of many inflammatory mediators, notably tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (4). Although TNF-α is of critical importance for eliminating infection (12), excessive TNF-α secretion can lead to septic shock and death (35).

The identification of molecular targets in LPS-induced cell activation (5) has provided a rational basis for the design of novel sepsis drugs, e.g., antibodies that neutralize or block LPS, CD14, or TNF-α. Most of these experimental antisepsis agents, however, failed to improve clinical outcome (14). The difficulties encountered in attempts to neutralize LPS effects are illustrated by the opposing properties of two LBPs which share extensive sequence identity, i.e., LBP and bactericidal permeability-increasing protein (BPI) (32). Whereas LBP represents one of the most potent LPS enhancers, BPI possesses potent LPS-neutralizing properties, resulting in reduced TNF-α release induced by gram-negative bacteria (36). However, despite favorable in vitro results, BPI has not emerged as an antisepsis drug (14, 15). CAP37, another LBP, attracts monocytes (7) and enhances LPS-induced TNF-α production (18). Interestingly, mutagenesis of the putative LPS-binding sequence of CAP37 (22) did not alter LPS binding or LPS-induced monocyte activation (27), suggesting that this putative LPS-binding sequence might not be required for the enhancement of LPS responses.

In this study, we aimed to identify common structural elements in cationic polypeptides that mediate LPS-enhancing effects. We hypothesized that physicochemical characteristics, e.g., the presence of charged amino acid residues rather than specific sequence motifs, would determine whether a particular polypeptide possesses LPS-enhancing properties. We found that various naturally occurring as well as synthetic cationic polypeptides enhanced LPS-induced inflammatory responses in human whole blood. We show that the LPS-enhancing effects of various cationic polypeptides are largely mediated by arginine residues. These findings point to the existence of a novel mechanism by which host responses to gram-negative endotoxin are modified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Histopaque-1077 Hybri-Max, RPMI 1640 medium, phosphate-buffered saline, Escherichia coli O111:B4 LPS, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated LPS (LPS-FITC), FITC-conjugated heparin (heparin-FITC), poly-l-glutamic acid, poly-l-aspartic acid, poly-l-asparagine, poly-l-tyrosine, poly-l-lysine, poly-l-arginine, l-lysine, and agarose-immobilized bovine serum albumin (BSA), heparin, protamines, and l-arginine were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). l-Arginine was from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Protamin 1000 (arginine-rich low-molecular-weight protein [100 IU = 1.0 mg]) and Liquemin (sodium salt of unfractionated heparin [100 IU = 0.625 mg]) were from F. Hoffmann-La Roche (Basel, Switzerland). My4, a neutralizing murine monoclonal antibody against human CD14, was purchased from the Coulter Corporation (Miami, Fla.). Recombinant human CAP37 (31) was generously provided by Hans Flodgaard (Leukotech, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Whole blood assay.

Human whole blood was obtained from healthy donors and collected in EDTA and acid-citrate-dextrose Vacutainers (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.). Citrated whole blood was immediately diluted 1:1 in RPMI 1640 medium. LPS, CAP37, protamines, unfractionated heparin, poly-l-amino acids, l-lysine, l-arginine, or My4 monoclonal antibodies were added as described elsewhere in the text. Samples were incubated for 4 h at 37°C, and secreted IL-8 levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Monocyte counts were determined in EDTA blood by endogenous peroxidase staining and flow cytometric analysis (ADVIA120; Bayer Diagnostics, Munich, Germany). Where indicated, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were separated from polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) by Histopaque-1077 density gradient centrifugation as described previously (26).

ELISA.

After incubation at 37°C, diluted whole blood samples were centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min and the supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C. MaxiSorp Surface Nunc-Immuno plates (Life Technologies Invitrogen, Basel, Switzerland) were coated overnight at 4°C in 0.1 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.5) by using a monoclonal anti-human IL-8 antibody (OptEIA) from Becton Dickinson PharMingen (Franklin Lakes, N.J.). Samples were thawed, and IL-8 concentrations were determined by using a OptEIA system (Becton Dickinson PharMingen). A Titertek Multiskan microplate reader from ICN Pharmaceuticals Flow Laboratories (Costa Mesa, Calif.) was used to measure absorbance.

Fibrinogen concentrations.

Bovine thrombin (NobiClot Fibrinogen; Nobis, Endingen, Germany) was added to diluted plasma samples, and clotting times were determined mechanically by using an AMAX CS190 device (Sigma). Clotting times were converted into fibrinogen concentrations by using a conversion table provided by Nobis.

Thrombin clotting times.

Thrombin clotting times were determined by using bovine thrombin from Diagnotec (Liestal, Switzerland) in combination with an AMAX CS190 device (Sigma).

Fluorescence measurements.

A total of 50 μl of packed agarose beads conjugated to BSA, heparin, protamines, or l-arginines was washed in RPMI 1640 medium and incubated with or without 10 μg of heparin-FITC/ml and/or 10 μg of LPS-FITC/ml. Where indicated, 10 μg of poly-l-arginine/ml, 100 IU of protamines/ml, or 100 μg of CAP37/ml was added, and the samples were left overnight at 4°C in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Agarose beads were washed extensively in phosphate-buffered saline, and bound fluorescence levels were measured by using a FLUOstar SLT microplate fluorescence reader (TECAN Group Ltd., Mannedorf, Switzerland) or a SPECTRAmax GEMINI XS Microplate Spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, Calif.).

Statistical analysis.

The sample number, mean value, and standard deviation of each data group were used to perform a one-way analysis of variance by using Fisher's probable least-squares difference test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

CAP37 and protamines enhance LPS-induced IL-8 production in human whole blood.

The ability of the cationic protein CAP37 to enhance LPS responses was originally shown by detection of increased TNF-α production in isolated human monocytes (18, 19). To test whether these findings are of physiological relevance, we aimed to investigate the effects of CAP37 on LPS-induced IL-8 production in whole blood. We first established conditions under which monocytes but not neutrophils (13, 33) become the main source of IL-8 in LPS-treated whole blood. Density gradient fractionation of a human whole blood sample showed that PBMC are indeed the predominant IL-8-producing cells when low LPS concentrations and short incubation times are used. Fractions enriched with either PBMC or PMN were treated with 10 ng of LPS/ml for 4 h. PBMC (106), in a sample consisting of 85% lymphocytes and 15% monocytes, released 1,700 pg of IL-8. Under identical conditions, 106 PMN produced 25 pg of IL-8. Therefore, even though 10 times more PMN were present in the blood sample, the contribution of PBMC to the total production of IL-8 remained within a range of 80 to 90%. This result was consistent with that of a subsequent whole blood experiment, in which we observed an almost complete loss of LPS-induced IL-8 production in the presence of antibodies which specifically block the monocyte differentiation antigen (16) and LPS receptor (32), CD14 (see Fig. 5).

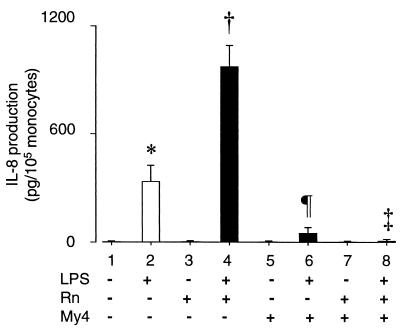

FIG. 5.

Effect of CD14 antibody blockade on poly-l-arginine-mediated enhancement of LPS-induced IL-8 production in human whole blood. Citrated whole blood from healthy donors was diluted 1:1 with RPMI 1640 medium and left untreated or preincubated for 1 h at room temperature with anti-CD14 murine monoclonal antibodies (My4; 10 μg/ml). Samples were then left untreated or treated for 4 h with LPS (10 ng/ml) and/or poly-l-arginine (Rn; 10 μg/ml). IL-8 levels were measured by ELISA. Values are means ± standard deviations (n = 4 donors); * versus †, * versus ¶, † versus ‡, P < 0.05.

Several other findings argue in favor of low-dose and short-term LPS treatment as used throughout this study. First, direct effects of LPS can be assessed only during the first hours of stimulation, i.e., before the maximum IL-8 secretion level is reached (10). Longer incubation times result in an accumulation of TNF-α and IL-1, both of which stimulate the release of IL-8 (11). Secondly, under the conditions described above, low and high LPS concentrations were equally effective in stimulating the production of IL-8. Normalized to 105 monocytes (among healthy individuals, up to fivefold differences in peripheral blood monocyte counts are frequently observed), 10 ng of LPS/ml led to the production of 210 ± 160 pg of IL-8/ml whereas 1 μg of LPS/ml stimulated the release of 250 ±200 pg of IL-8/ml during a 4-h incubation period (n = 5 donors). Finally, relevant plasma LPS concentrations such as those observed in septic shock are within a nanograms-per-millimeter (37) rather than a micrograms-per-millimeter range. In our study, IL-8 levels in LPS-stimulated whole blood were the result of de novo synthesis by monocytes and were not due to a release of preformed cell-associated IL-8 (28). This was shown by the complete inhibition of LPS-induced IL-8 production in the presence of antibodies which selectively block monocytic CD14 (see Fig. 5).

Having established conditions under which LPS activation of monocytes can be studied in whole blood, we first assessed the effect of the presence of CAP37 on LPS-induced IL-8 production. CAP37 alone did not stimulate IL-8 release (Fig. 1, lane 3); however, if LPS and CAP37 were added simultaneously, IL-8 secretion rose significantly above the levels produced by the addition of LPS alone (Fig. 1, lanes 2 and 4 [P < 0.05]). To test whether the observed enhancing effect on LPS-induced monocyte activation could be related to the cationic nature of CAP37, we examined the effect of the presence of protamines, a mixture of small arginine-rich and highly cationic proteins. Protamines alone had no effect (Fig. 1, lane 5), but in combination with LPS, protamines resulted in significant amplification of the LPS signal (Fig. 1, lanes 2 and 6 [P < 0.05]). These results suggested a possible role for arginine residues in the enhancement of LPS signals.

FIG. 1.

Effect of arginine-rich cationic proteins on LPS-induced IL-8 production in human whole blood. Citrated whole blood from healthy donors was diluted 1:1 with RPMI 1640 medium and left untreated or treated for 4 h with LPS (10 ng/ml), CAP37 (25 μg/ml), and Protamin (protamines; 100 IU/ml). IL-8 levels were measured by ELISA. Values are means ± standard deviations (n = 4 donors); * versus †, P < 0.05.

Complex formation of protamines with heparin further enhances LPS-induced IL-8 production.

Heparin, a polysulfated carbohydrate, is widely used in clinical practice to inhibit coagulation. Protamines, which form high-affinity complexes with heparin (24), are also used clinically to neutralize heparin's anticoagulatory effects. Previous studies have shown that heparin enhances LPS-induced activation of monocytes (20). More recent evidence suggests that this enhancement is mediated by heparin's sulfate residues (M. Heinzelmann and H. Bosshart, submitted for publication). We tested whether heparin and protamines would each neutralize the LPS-enhancing effect of the other when added together to human whole blood. When added alone, both heparin and protamines increased LPS-induced IL-8 production (Fig. 2A, lanes 4 and 6 [P < 0.05] and lanes 4 and 8 [P < 0.05]). However, when protamines were mixed with heparin and added along with LPS, no neutralizing effect was observed (Fig. 2A, lanes 9 and 10). Instead, simultaneous addition of heparin and protamines increased IL-8 levels even further (Fig. 2A, lanes 6 and 10 [P < 0.05]), suggesting that heparin and protamines enhance LPS effects by different mechanisms.

FIG. 2.

Effect of protamine-heparin complexes on LPS-induced IL-8 release in human whole blood. Citrated whole blood from healthy donors was diluted 1:1 with RPMI 1640 medium and left untreated or treated for 4 h with LPS (10 ng/ml), Liquemin (heparin; 10 or 100 IU/ml), and Protamin (protamines; 100 IU/ml [black bars]). (A) IL-8 levels were measured by ELISA. Values are means ± standard deviations (n = 4 donors); * versus † and ¶ versus ‡, P < 0.05. (B) Thrombin clotting times (in seconds) were measured as described in Materials and Methods. Thrombin clotting times exceeding 200 s are represented by bar lengths of 200 s. Values are means ± standard deviations (n = 4 donors). (C) Fibrinogen concentrations (in grams per liter [g/l]) were measured as described in Material and Methods; * versus †, P < 0.05.

To demonstrate that simultaneous addition of heparin and protamines yields heparin-protamine complexes, we examined the effects of heparin-protamine mixtures on the parameters of coagulation. As judged by a prolongation of thrombin clotting times, 10 or 100 IU of heparin/ml effectively inhibited coagulation in human whole blood (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 to 3). The presence of LPS, either alone or in combination with heparin, had no effect on thrombin clotting times (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 to 6). Consistent with previous reports (8), protamines alone did not affect thrombin clotting times (Fig. 2B, lane 7). The addition of protamines to heparin samples restored thrombin clotting times to baseline levels (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 and 4 and lanes 7 to 10), demonstrating a heparin-neutralizing effect of protamines which, in turn, depends on the formation of complexes of heparin with protamines.

Measuring plasma fibrinogen concentrations confirmed these results. With or without LPS, addition of heparin resulted in reduced fibrinogen levels (Fig. 2C, lanes 1 to 3 and lanes 4 to 6 [P < 0.05]). When heparin and protamines were combined, fibrinogen levels remained unchanged (Fig. 2C, lanes 9 and 10).

Synthetic poly-l-arginine and poly-l-lysine are potent amplifiers of LPS-induced IL-8 production.

Having shown that different naturally occurring arginine-rich cationic proteins enhance LPS-induced IL-8 production, we next asked whether the presence of positively charged residues, e.g., l-lysine or l-arginine, in polypeptide chains was sufficient to enhance LPS signals. To this end, we added, together with LPS, various synthetic poly-l-amino acids to diluted human whole blood and monitored plasma IL-8 levels. The presence of negatively charged poly-l-glutamic acid or poly-l-aspartic acid had no effect on LPS-induced IL-8 production (Fig. 3, lanes 2, 4, and 6). Similarly, poly-l-asparagine and poly-l-tyrosine, two neutral poly-l-amino acids, did not interfere with LPS monocyte activation (Fig. 3, lanes 2, 8, and 10). The addition of poly-l-lysine or poly-l-arginine, however, increased LPS-induced IL-8 production significantly (Fig. 3, lanes 2, 12, and 14 [P < 0.05]), with poly-l-arginine emerging as the most potent amplifier of LPS responses. These data showed that the LPS-enhancing effects of basic polypeptides were associated with positively charged arginine or lysine residues.

FIG. 3.

Effect of synthetic poly-l-amino acids on IL-8 production in LPS-stimulated human whole blood. Citrated whole blood from healthy donors was diluted 1:1 with RPMI 1640 medium and treated for 4 h with LPS (10 ng/ml) and/or poly-l-amino acid (Xn; 10 μg/ml), alone or with poly-l-glutamic acid (E), poly-l-aspartic acid (D), poly-l-asparagine (N), poly-l-tyrosine (Y), poly-l-lysine (K), or poly-l-arginine (R). IL-8 levels were measured by ELISA. Values are means ± standard deviations (n = 4 donors); * versus †, P < 0.05.

Free l-lysine and free l-arginine do not affect LPS-induced IL-8 production.

To further investigate the role of l-lysine and l-arginine residues in LPS activation, we tested the effects of free l-lysine and free l-arginine in LPS-stimulated whole blood. At a concentration of 1 mg/ml, l-lysine and l-arginine did not enhance LPS-induced IL-8 production significantly (Fig. 4, lanes 2, 4, and 6). To test whether free l-amino acids competed with the corresponding polypeptide-resident l-amino acids, we mixed protamines with excess free l-arginine or l-lysine and measured the effect on IL-8 release after LPS stimulation. Protamines amplified LPS responses irrespective of whether free l-lysine or l-arginine was present (Fig. 4, lanes 7, 8, and 9). Similar results were obtained when CAP37, poly-l-lysine, or poly-l-arginine was used instead of protamines (data not shown). These results indicated that basic polypeptides, but not basic amino acids, function as enhancers of LPS signals.

FIG. 4.

Effect of free l-arginine and free l-lysine on protamine-mediated enhancement of LPS-induced IL-8 production in human whole blood. Citrated whole blood from healthy donors was diluted 1:1 with RPMI 1640 medium and left untreated or treated for 4 h with LPS (10 ng/ml), free l-lysine (K; 1 mg/ml), free l-arginine (R; 1 mg/ml), and Protamin (protamines; 100 IU/ml). IL-8 levels were measured by ELISA. Values are means ± standard deviations (n = 4 donors); * versus †, P < 0.05.

Blockade of the human LPS receptor, CD14, abolishes the effect of poly-l-arginine on amplification of LPS-induced IL-8 production.

Recent work has shown that an antibody blockade of CD14 inhibits CAP37-mediated enhancement of LPS-induced TNF-α production in isolated human monocytes (19). We examined whether the enhancement of LPS responses by poly-l-arginine showed a similar CD14 dependency. After preincubation of human whole blood with My4, a neutralizing murine monoclonal antibody against human CD14, LPS no longer induced IL-8 production (Fig. 5, lanes 2 and 6). This result provided conclusive evidence that monocytes were indeed the main source of LPS-induced IL-8 in our whole blood assay. As shown earlier (Fig. 3, lanes 2 and 14), poly-l-arginine enhanced LPS-induced IL-8 production (Fig. 5, lanes 2 and 4) yet pretreatment with My4 completely abolished this effect (Fig. 5, lanes 4 and 8). These observations excluded an involvement of alternative LPS receptors such as CD11b/CD18 (21, 30) or scavenger receptors (17) in mediating poly-l-arginine-induced enhancement of LPS responses.

Protamines are LBPs.

We next examined whether protamines bind LPS specifically. Agarose beads carrying either anionic BSA or cationic protamines were equilibrated with heparin-FITC (Fig. 6A) or LPS-FITC (Fig. 6B). Neither heparin-FITC nor LPS-FITC bound to BSA-agarose specifically (Fig. 6A and B, lanes 1 and 2). As expected, heparin-FITC showed a clear affinity to protamines (Fig. 6A, lanes 3 and 4). Interestingly, LPS-FITC also exhibited an affinity to protamines (Fig. 6B, lanes 3 and 4). This finding was verified by a series of additional experiments. Firstly, the binding of LPS-FITC to protamines was saturable and was inhibited by the addition of excess unconjugated LPS (Fig. 6C). Secondly, the binding of LPS-FITC to immobilized protamines was inhibited by the addition of soluble protamines (Fig. 6D, lanes 1 and 2). Finally, LPS-FITC was recruited onto immobilized heparin by the addition of soluble protamines (Fig. 6D, lanes 3 and 4). Further evidence that arginine residues are critically involved in LPS binding was obtained by incubating agarose-immobilized l-arginines with LPS-FITC in the presence or absence of different arginine-rich structures (Fig. 6E). Poly-l-arginines, protamines, and CAP37 were all effective in inhibiting the interaction of LPS-FITC with immobilized l-arginines (Fig. 6E, lanes 3, 4, and 5). These observations suggested that arginine residues mediate LPS binding to arginine-rich cationic polypeptides.

FIG. 6.

Binding of LPS-FITC to protamines. Packed agarose (50 μl) with covalently linked BSA (BSA-agarose), agarose-immobilized heparin (heparin-agarose), or agarose-immobilized protamines (protamine-agarose) were incubated with heparin-FITC or LPS-FITC in the presence or absence of poly-l-arginine (Rn), protamines, or CAP37. Agarose beads were washed, and bound fluorescence levels were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Values are means ± standard deviations and are expressed as percentages of maximum fluorescence (n = 3 samples). (A) Binding of soluble heparin-FITC to immobilized protamines. (B) Binding of soluble LPS-FITC to immobilized protamines. (C) Saturation and competition of LPS-FITC binding to immobilized protamines. To demonstrate displacement of protamine-bound LPS-FITC, 500 μg of LPS/ml was added, together with 5 μg of LPS-FITC/ml. (D) Binding of LPS-FITC to soluble protamines. The addition of soluble protamines led to displacement of LPS-FITC from immobilized protamines (1, 2). Soluble protamines capture LPS-FITC in solution (3, 4). (E) Competition of LPS-FITC binding to immobilized l-arginines. The diverse arginine-rich structures (Rn), protamines, and CAP37 all inhibit the interaction between LPS-FITC and immobilized l-arginines.

DISCUSSION

Binding of LPS has been described previously for full-length CAP37 (29) as well as for a synthetic peptide which corresponds to amino acid residues 20 to 44 of CAP37 (6). Enhancing effects of LPS-induced inflammatory responses, on the other hand, have been reported for full-length CAP37 (18, 19) but not for the short CAP37-derived LPS-binding peptide (6). Resolution of the CAP37 structure revealed that many of the basic residues are clustered and form a cationic patch (22). The LPS-enhancing effects of CAP37 could, theoretically, be linked to an abundance of basic residues; however, this is difficult to prove, because targeted mutagenesis of arginine residues would alter 10% of the entire protein. In the present study, we provide evidence that in an intact physiological system such as human whole blood, LPS-enhancing effects can be caused by many different cationic polypeptides. We identified basic amino acid residues, in particular arginines, as a common structural element, capable of mediating LPS enhancement.

Protamines are a group of small arginine-rich and highly cationic sperm nuclear basic proteins which replace histones in chromosome packing at a late stage of spermatogenesis (1). Protamines are also used clinically to neutralize the anticoagulatory effects of heparin, a polysulfated mast cell glycosaminoglycan with an ability to enhance LPS-induced monocyte activation (20). The observation that heparin and protamines did not neutralize their LPS-enhancing effects (Fig. 2) indicates that the complex tertiary structures of both heparin and protamines are not of critical importance for LPS enhancement.

Further analysis revealed that the presence of synthetic l-arginine or l-lysine polymers enhanced LPS responses in a manner similar to that of CAP37 or protamines (Fig. 3). As charged poly-l-amino acids only exist in random coils (9), particular secondary structures are unlikely to play a role in arginine-mediated LPS enhancement. The complete elimination of poly-l-arginine-enhanced LPS responses upon antibody blockading of CD14 (Fig. 5), combined with the fact that immobilized l-arginines bind LPS (Fig. 6), points to a mechanism in which LPS is captured by basic polypeptides in solution prior to CD14-dependent activation of monocytes.

It is important to emphasize that LPS enhancement is not determined by the abundance of a particular basic amino acid alone. For example, serum albumin, an abundant plasma protein, contains more arginine and lysine residues than human CAP37 and protamine 2B from salmon combined (Fig. 7). However, serum albumin is anionic overall and does not affect LPS responses. Although the experiments presented here strongly argue for a role of arginine residues in conferring LPS-enhancing properties to cationic polypeptides, they do not rule out the possibility that certain anionic polypeptides are able to sensitize host cells to LPS. LBP and CD14, as well as the extracellular domain of TLR4, are all required for initiation of LPS responses, yet the human forms of these proteins are all anionic (Fig. 7). Another example is the binding of LPS to cell-free hemoglobin (25), which does not involve electrostatic interactions, indicating that arginine residues might not be involved. The presence of cell-free hemoglobin, however, is sufficient to enhance LPS responses (25) and to increase mortality in experimental animals with induced peritonitis (34).

FIG. 7.

Physicochemical properties of LBPs. Anionic human CD14 (hCD14) and human LBP (hLBP) bind LPS and confer responsiveness to the presence of low LPS concentrations. In the presence of LPS, extracellular domains of human TLR4 (hTLR4e) interact with CD14 and initiate cellular activation. Human serum albumin (hSA), an abundant plasma protein rich in basic residues (K, l-lysine; R, l-arginine) but with an overall negative charge, does not bind LPS or interfere with LPS activation. Cationic human CAP37 (hCAP37) or salmon protamine 2B (sProtamine 2B) binds LPS and amplifies LPS responses. The positions along the y axis represent the sums of basic residues in each protein. Relative overall protein charges (net charge number: anionic, open circles; cationic, closed circles) represent the differences between positively (K + R) and negatively (glutamic acid and aspartic acid) charged residues. Not represented are possible posttranslational modifications such as the addition of negatively charged sialic acid or sulfate residues.

On the basis of findings regarding the extensive sequence homology of the human forms of BPI and LBP (32) and the recently resolved crystal structure of BPI (2), Beamer and coworkers predicted a basic cluster near the N terminus of LBP (3). The authors of that work further suggested that the residues which form this basic cluster might be free to interact with the negatively charged phosphate groups in the lipid A portion of LPS if they are not engaged in interresidue interactions (3). Conceivably, cationic arginine-rich polypeptides (e.g., protamines) are more likely to contain basic clusters without structural function, which could explain why some of these polypeptides bind LPS and enhance LPS responses. Synthetic poly-l-arginines or poly-l-lysines represent extreme examples of cationic polypeptides, because all arginine or lysine residues are free to interact with negatively charged groups (e.g., the phosphate groups of LPS).

LBP, the most potent LPS-enhancing protein, binds LPS and specifically transfers LPS to CD14 (38). Human CAP37 has affinities to both LPS (22) and monocytes (18) but does not specifically recognize CD14 (18). Poly-l-lysines, on the other hand, do not specifically recognize monocytes but bind to all cellular surfaces. Binding of poly-l-lysines to cells is widely used to induce attachment of nonadherent cells to poly-l-lysine-coated surfaces. Binding of cationic polypeptide-LPS complexes to monocytes might be sufficient to facilitate the transfer of LPS to CD14, resulting in enhanced LPS responses.

Acknowledgments

We thank the volunteers who participated in this study. We especially thank Jan A. Fischer (Research Laboratory for Calcium Metabolism, Balgrist Orthopedic University Hospital, Zurich, Switzerland) for his generous support.

This study was funded in part by Novartis (grant no. 99C45), the Olga Mayenfisch Research Foundation (grant no. 232042), and the AO Research Commission (grant no. 2000-H23).

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausio, J. 1999. Histone H1 and evolution of sperm nuclear basic proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 274:31115-31118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beamer, L. J., S. F. Carroll, and D. Eisenberg. 1997. Crystal structure of human BPI and two bound phospholipids at 2.4 angstrom resolution. Science 276:1861-1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beamer, L. J., S. F. Carroll, and D. Eisenberg. 1998. The BPI/LBP family of proteins: a structural analysis of conserved regions. Protein Sci. 7:906-914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beutler, B. 2000. Tlr4: central component of the sole mammalian LPS sensor. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12:20-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beutler, B. 2000. Endotoxin, toll-like receptor 4, and the afferent limb of innate immunity. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:23-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brackett, D. J., M. R. Lerner, M. A. Lacquement, R. He, and H. A. Pereira. 1997. A synthetic lipopolysaccharide-binding peptide based on the neutrophil-derived protein CAP37 prevents endotoxin-induced responses in conscious rats. Infect. Immun. 65:2803-2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chertov, O., H. Ueda, L. L. Xu, K. Tani, W. J. Murphy, J. M. Wang, O. M. Howard, T. J. Sayers, and J. J. Oppenheim. 1997. Identification of human neutrophil-derived cathepsin G and azurocidin/CAP37 as chemoattractants for mononuclear cells and neutrophils. J. Exp. Med. 186:739-747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu, A. J., Z. G. Wang, M. Raicu, S. Beydoun, and N. Ramos. 2001. Protamine inhibits tissue factor-initiated extrinsic coagulation. Br. J. Haematol. 115:392-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuff, J. A., and G. J. Barton. 2000. Application of multiple sequence alignment profiles to improve protein secondary structure prediction. Proteins 40:502-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeForge, L. E., and D. G. Remick. 1991. Kinetics of TNF, IL-6, and IL-8 gene expression in LPS-stimulated human whole blood. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 174:18-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeForge, L. E., J. S. Kenney, M. L. Jones, J. S. Warren, and D. G. Remick. 1992. Biphasic production of IL-8 in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated human whole blood. Separation of LPS- and cytokine-stimulated components using anti-tumor necrosis factor and anti-IL-1 antibodies. J. Immunol. 148:2133-2141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Echtenacher, B., W. Falk, D. N. Mannel, and P. H. Krammer. 1990. Requirement of endogenous tumor necrosis factor/cachectin for recovery from experimental peritonitis. J. Immunol. 145:3762-3766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujishima, S., A. R. Hoffman, T. Vu, K. J. Kim, H. Zheng, D. Daniel, Y. Kim, E. F. Wallace, J. W. Larrick, and T. A. Raffin. 1993. Regulation of neutrophil interleukin 8 gene expression and protein secretion by LPS, TNF-alpha, and IL-1 beta. J. Cell Physiol. 154:478-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garber, K. 2000. Protein C may be sepsis solution. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:917-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giroir, B. P., P. A. Quint, P. Barton, E. A. Kirsch, L. Kitchen, B. Goldstein, B. J. Nelson, N. J. Wedel, S. F. Carroll, and P. J. Scannon. 1997. Preliminary evaluation of recombinant amino-terminal fragment of human bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein in children with severe meningococcal sepsis. Lancet 350:1439-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goyert, S. M., E. Ferrero, W. J. Rettig, A. K. Yenamandra, F. Obata, and M. M. Le Beau. 1988. The CD14 monocyte differentiation antigen maps to a region encoding growth factors and receptors. Science 239:497-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hampton, R. Y., D. T. Golenbock, M. Penman, M. Krieger, and C. R. Raetz. 1991. Recognition and plasma clearance of endotoxin by scavenger receptors. Nature 352:342-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinzelmann, M., M. A. Mercer-Jones, H. Flodgaard, and F. N. Miller. 1998. Heparin-binding protein (CAP37) is internalized in monocytes and increases LPS-induced monocyte activation. J. Immunol. 160:5530-5536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinzelmann, M., H. C. Polk, Jr., and F. N. Miller. 1998. Modulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced monocyte activation by heparin-binding protein and fucoidan. Infect. Immun. 66:5842-5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinzelmann, M., M. Miller, A. Platz, L. E. Gordon, D. O. Herzig, and H. C. Polk, Jr. 1999. Heparin and enoxaparin enhance endotoxin-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in human monocytes. Ann. Surg. 229:542-550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingalls, R. R., B. G. Monks, R. Savedra, Jr., W. J. Christ, R. L. Delude, A. E. Medvedev, T. Espevik, and D. T. Golenbock. 1998. CD11/CD18 and CD14 share a common lipid A signaling pathway. J. Immunol. 161:5413-5420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iversen, L. F., J. S. Kastrup, S. E. Bjorn, P. B. Rasmussen, F. C. Wiberg, H. J. Flodgaard, and I. K. Larsen. 1997. Structure of HBP, a multifunctional protein with a serine proteinase fold. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:265-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang, Q., S. Akashi, K. Miyake, and H. R. Petty. 2000. Lipopolysaccharide induces physical proximity between CD14 and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) prior to nuclear translocation of NF-kappa B. J. Immunol. 165:3541-3544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones, G. R., R. Hashim, and D. M. Power. 1986. A comparison of the strength of binding of antithrombin III, protamine and poly(l-lysine) to heparin samples of different anticoagulant activities. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 883:69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jurgens, G., M. Muller, M. H. Koch, and K. Brandenburg. 2001. Interaction of hemoglobin with enterobacterial lipopolysaccharide and lipid A. Physicochemical characterization and biological activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:4233-4242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalmar, J. R., R. R. Arnold, M. L. Warbington, and M. K. Gardner. 1988. Superior leukocyte separation with a discontinuous one-step Ficoll-Hypaque gradient for the isolation of human neutrophils. J. Immunol. Methods 110:275-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kastrup, J. S., V. Linde, A. K. Pedersen, B. Stoffer, L. F. Iversen, I. K. Larsen, P. B. Rasmussen, H. J. Flodgaard, and S. E. Bjorn. 2001. Two mutants of human heparin binding protein (CAP37): toward the understanding of the nature of lipid A/LPS and BPTI binding. Proteins 42:442-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marie, C., C. Fitting, C. Cheval, M. R. Losser, J. Carlet, D. Payen, K. Foster, and J. M. Cavaillon. 1997. Presence of high levels of leukocyte-associated interleukin-8 upon cell activation and in patients with sepsis syndrome. Infect. Immun. 65:865-871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pereira, H. A., I. Erdem, J. Pohl, and J. K. Spitznagel. 1993. Synthetic bactericidal peptide based on CAP37: a 37-kDa human neutrophil granule-associated cationic antimicrobial protein chemotactic for monocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:4733-4737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perera, P. Y., T. N. Mayadas, O. Takeuchi, S. Akira, M. Zaks-Zilberman, S. M. Goyert, and S. N. Vogel. 2001. CD11b/CD18 acts in concert with CD14 and Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 to elicit full lipopolysaccharide and taxol-inducible gene expression. J. Immunol. 166:574-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rasmussen, P. B., S. Bjorn, S. Hastrup, P. F. Nielsen, K. Norris, L. Thim, F. C. Wiberg, and H. Flodgaard. 1996. Characterization of recombinant human HBP/CAP37/azurocidin, a pleiotropic mediator of inflammation-enhancing LPS-induced cytokine release from monocytes. FEBS Lett. 390:109-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schumann, R. R., S. R. Leong, G. W. Flaggs, P. W. Gray, S. D. Wright, J. C. Mathison, P. S. Tobias, and R. J. Ulevitch. 1990. Structure and function of lipopolysaccharide binding protein. Science 249:1429-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strieter, R. M., K. Kasahara, R. M. Allen, T. J. Standiford, M. W. Rolfe, F. S. Becker, S. W. Chensue, and S. L. Kunkel. 1992. Cytokine-induced neutrophil-derived interleukin-8. Am. J. Pathol. 141:397-407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su, D., R. I. Roth, M. Yoshida, and J. Levin. 1997. Hemoglobin increases mortality from bacterial endotoxin. Infect. Immun. 65:1258-1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tracey, K. J., B. Beutler, S. F. Lowry, J. Merryweather, S. Wolpe, I. W. Milsark, R. J. Hariri, T. J. Fahey III, A. Zentella, J. D. Albert, et al. 1986. Shock and tissue injury induced by recombinant human cachectin. Science 234:470-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiss, J., P. Elsbach, C. Shu, J. Castillo, L. Grinna, A. Horwitz, and G. Theofan. 1992. Human bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein and a recombinant NH2-terminal fragment cause killing of serum-resistant gram-negative bacteria in whole blood and inhibit tumor necrosis factor release induced by the bacteria. J. Clin. Investig. 90:1122-1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wessels, B. C., M. T. Wells, S. L. Gaffin, J. G. Brock-Utne, P. Gathiram, and L. B. Hinshaw. 1988. Plasma endotoxin concentration in healthy primates and during E. coli-induced shock. Crit. Care Med. 16:601-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright, S. D., R. A. Ramos, P. S. Tobias, R. J. Ulevitch, and J. C. Mathison. 1990. CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science 249:1431-1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]