Abstract

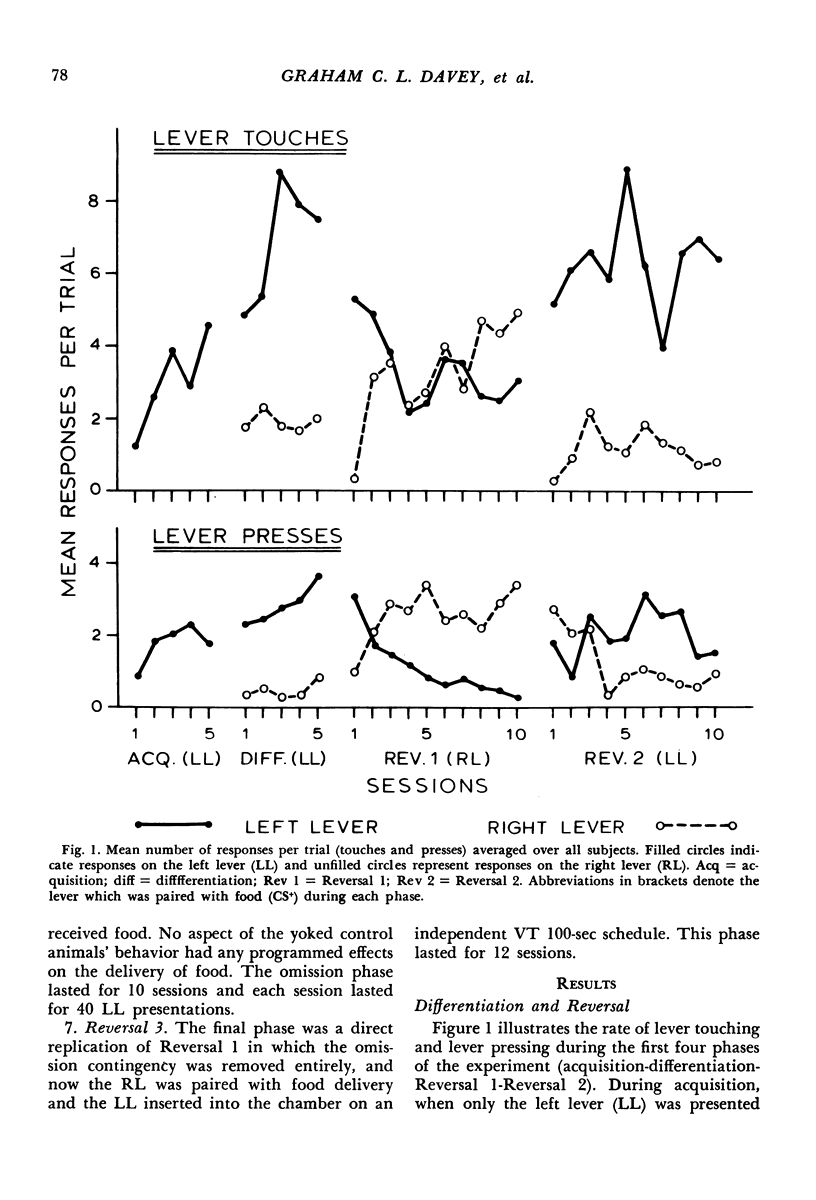

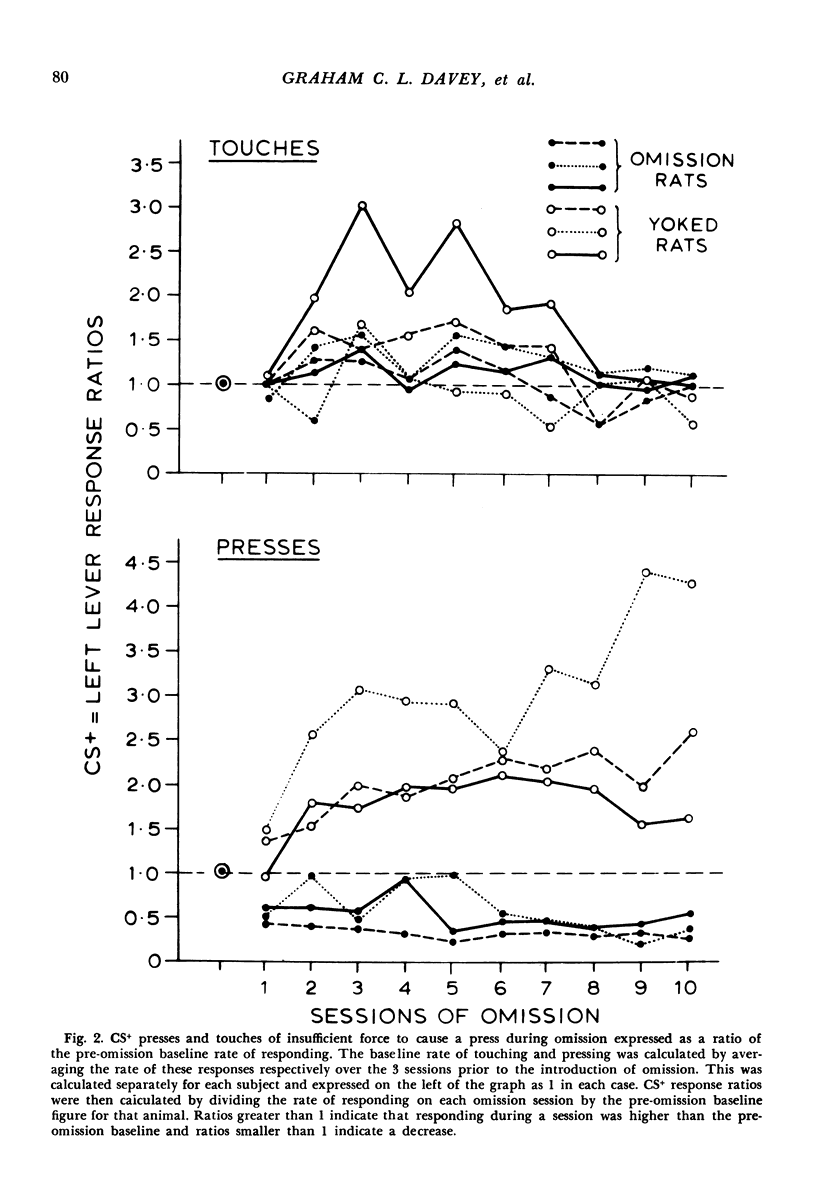

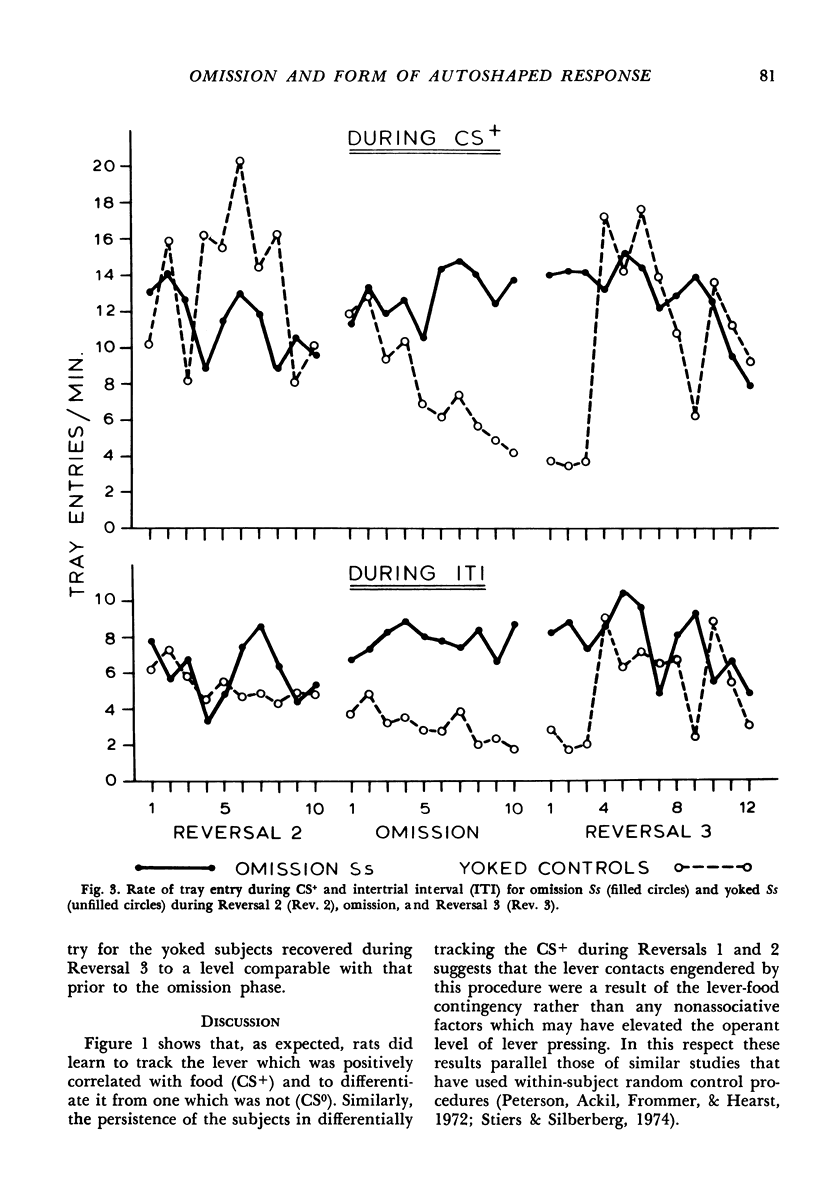

Two experiments were conducted to investigate the effect of an omission contingency on behavior related to and characterizing autoshaped lever contacts in the rat. In Experiment I an omission contingency imposed on autoshaped lever contacts forceful enough to produce a press (.078N) resulted in a significant decrease in lever presses, but had no effect on frequency of lever touches (contacts of insufficient force to produce a press) or rate of food tray entry during lever presentation. In contrast, rats which received a similar number of lever-food pairings, but whose behavior had no programmed consequences (yoked control subjects), showed an increase in lever press rate, a significant decrease in rate of food tray entry, and no change in rate of lever-touches. In Experiment II, the effect of a similar omission contingency on the topography of lever contact responses was investigated. Prior to omission training subjects contacted the lever primarily by pawing it. Following omission training this behavior was suppressed, with a subsequent increase in lever contacts characterized as nosing. Yoked control subjects showed no significant changes in lever contact topography. The results indicate that (1) an omission contingency does not simply eliminate wholesale those topographies which incur the contingency but produces subtle adaptive changes in lever contact topography; and (2) the nature of the autoshaped response in the rat does not appear to be rigid enough to depend solely upon the nature of the unconditioned stimulus or the conditioned stimulus, but can also be determined by the relationships existing between the animal's behavior and these stimuli.

Keywords: autoshaping, sign tracking, goal tracking, omission contingency, response topography, yoked control, rats

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Atnip G. W. Stimulus- and response-reinforcer contingencies in autoshaping, operant, classical, and omission training procedures in rats. J Exp Anal Behav. 1977 Jul;28(1):59–69. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1977.28-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera F. J. Centrifugal selection of signal-directed pecking. J Exp Anal Behav. 1974 Sep;22(2):341–355. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1974.22-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. L., Jenkins H. M. Auto-shaping of the pigeon's key-peck. J Exp Anal Behav. 1968 Jan;11(1):1–8. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1968.11-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland P. C. Conditioned stimulus as a determinant of the form of the Pavlovian conditioned response. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1977 Jan;3(1):77–104. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.3.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland P. C. Differential effects of omission contingencies on various components of Pavlovian appetitive conditioned responding in rats. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1979 Apr;5(2):178–193. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.5.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland P. C. Influence of visual conditioned stimulus characteristics on the form of Pavlovian appetitive conditioned responding in rats. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1980 Jan;6(1):81–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins H. M., Moore B. R. The form of the auto-shaped response with food or water reinforcers. J Exp Anal Behav. 1973 Sep;20(2):163–181. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1973.20-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locurto C., Terrace H. S., Gibbon J. Autoshaping, random control, and omission training in the rat. J Exp Anal Behav. 1976 Nov;26(3):451–462. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1976.26-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson G. B., Ackilt J. E., Frommer G. P., Hearst E. S. Conditioned Approach and Contact Behavior toward Signals for Food or Brain-Stimulation Reinforcement. Science. 1972 Sep 15;177(4053):1009–1011. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4053.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reberg D., Mann B., Innis N. K. Superstitious behavior for food and water in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1977 Dec;19(6):803–806. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(77)90318-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz B. Studies of operant and reflexive key pecks in the pigeon. J Exp Anal Behav. 1977 Mar;27(2):301–313. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1977.27-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz B., Williams D. R. The role of the response-reinforcer contingency in negative automaintenance. J Exp Anal Behav. 1972 May;17(3):351–357. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1972.17-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz B., Williams D. R. Two different kinds of key peck in the pigeon: some properties of responses maintained by negative and positive response-reinforcer contingencies. J Exp Anal Behav. 1972 Sep;18(2):201–216. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1972.18-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiers M., Silberberg A. Lever-contact responses in rats: automaintenance with and without a negative response-reinforcer dependency. J Exp Anal Behav. 1974 Nov;22(3):497–506. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1974.22-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Williams H. Auto-maintenance in the pigeon: sustained pecking despite contingent non-reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1969 Jul;12(4):511–520. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1969.12-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]