Abstract

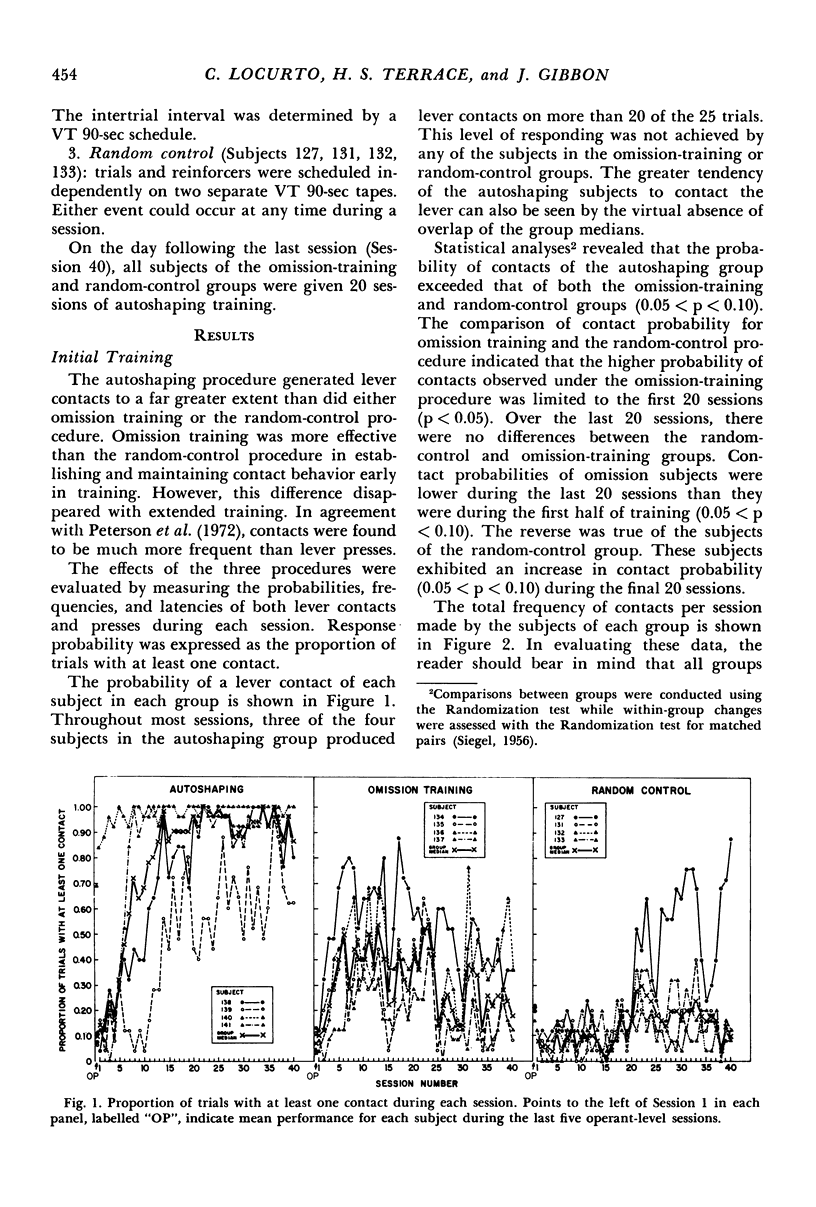

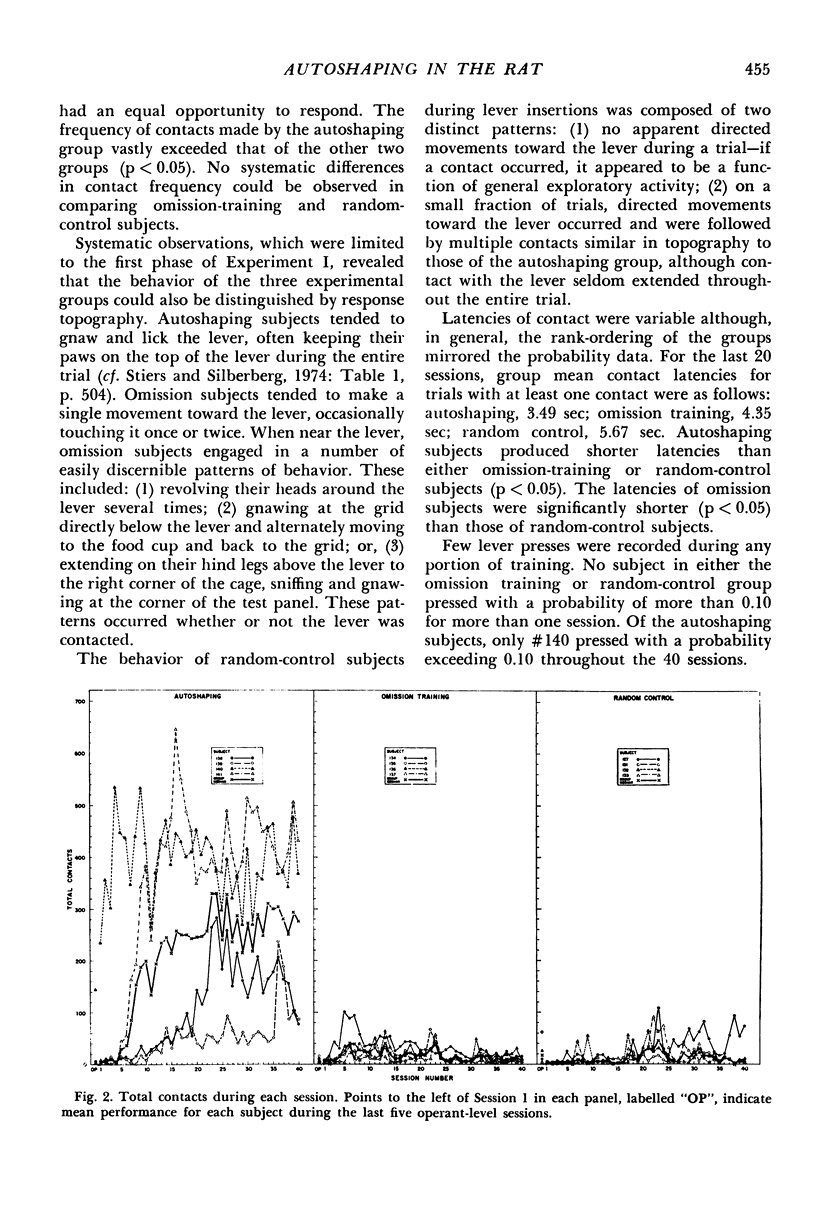

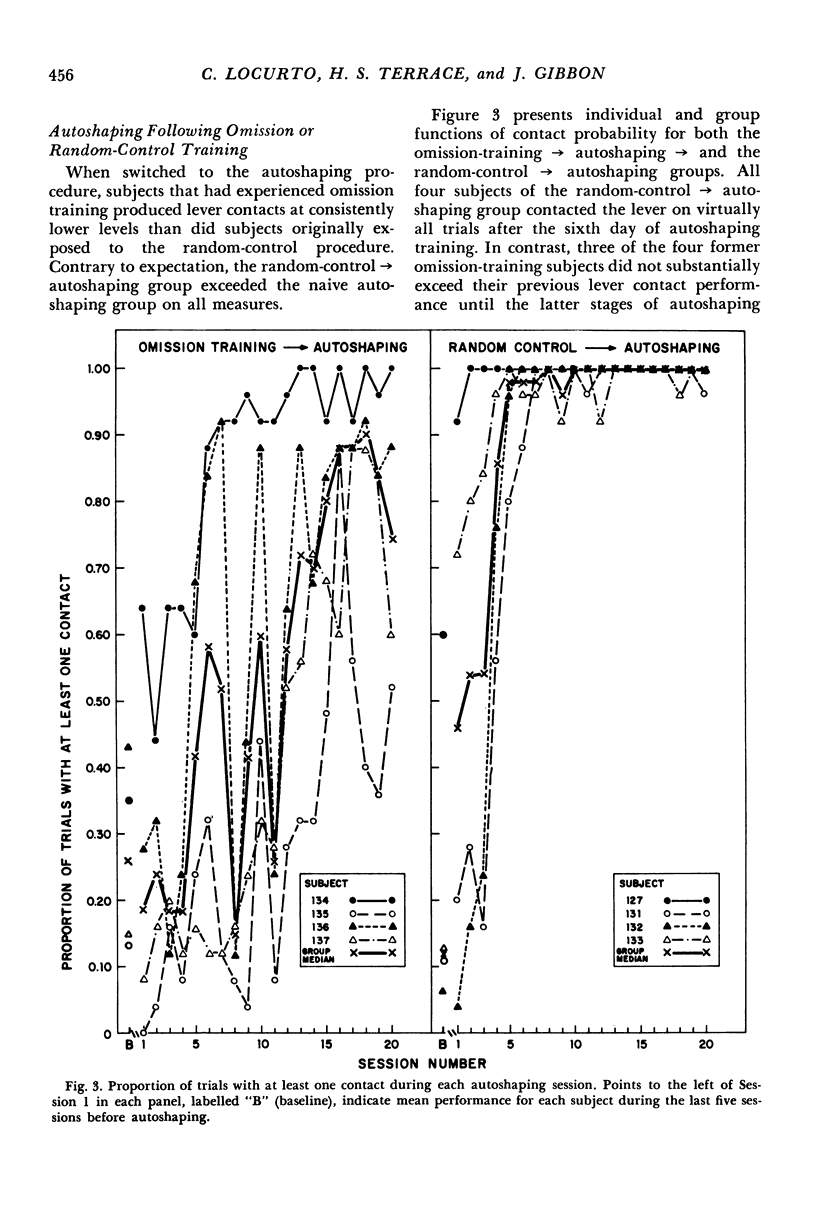

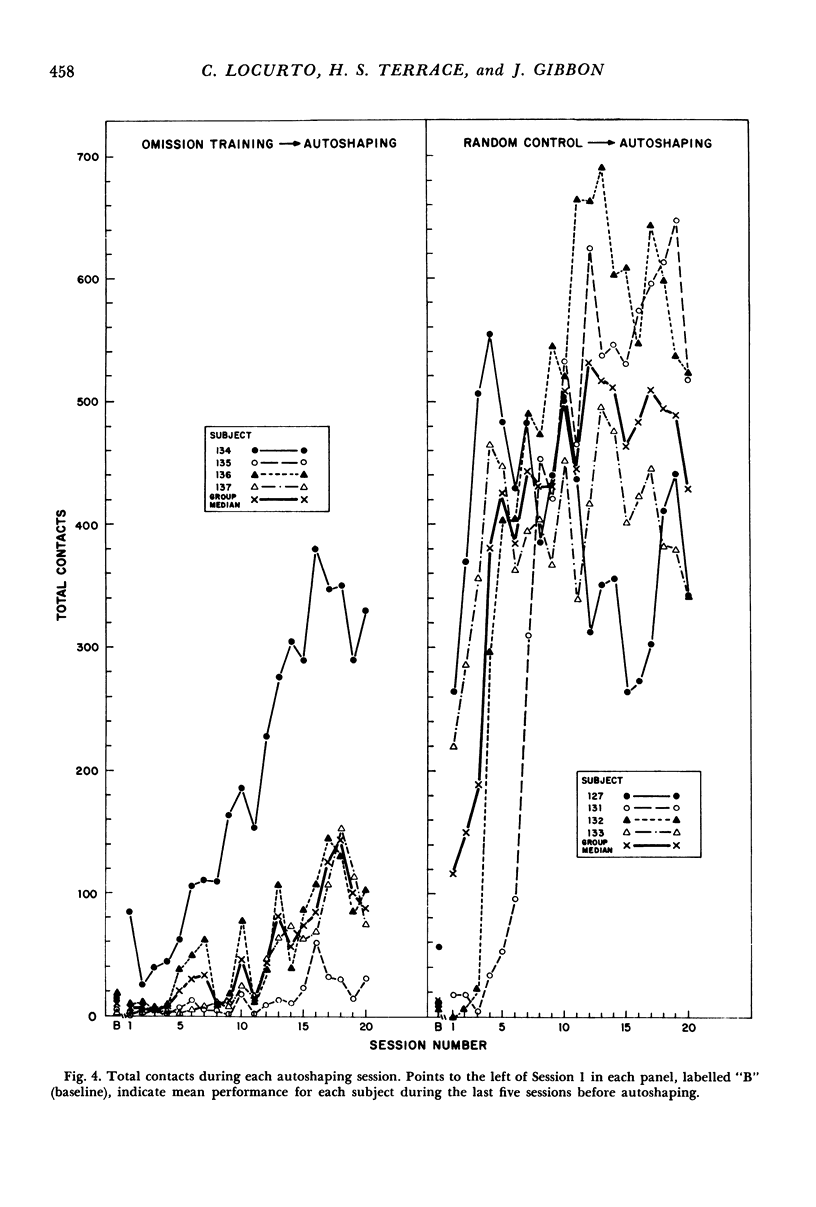

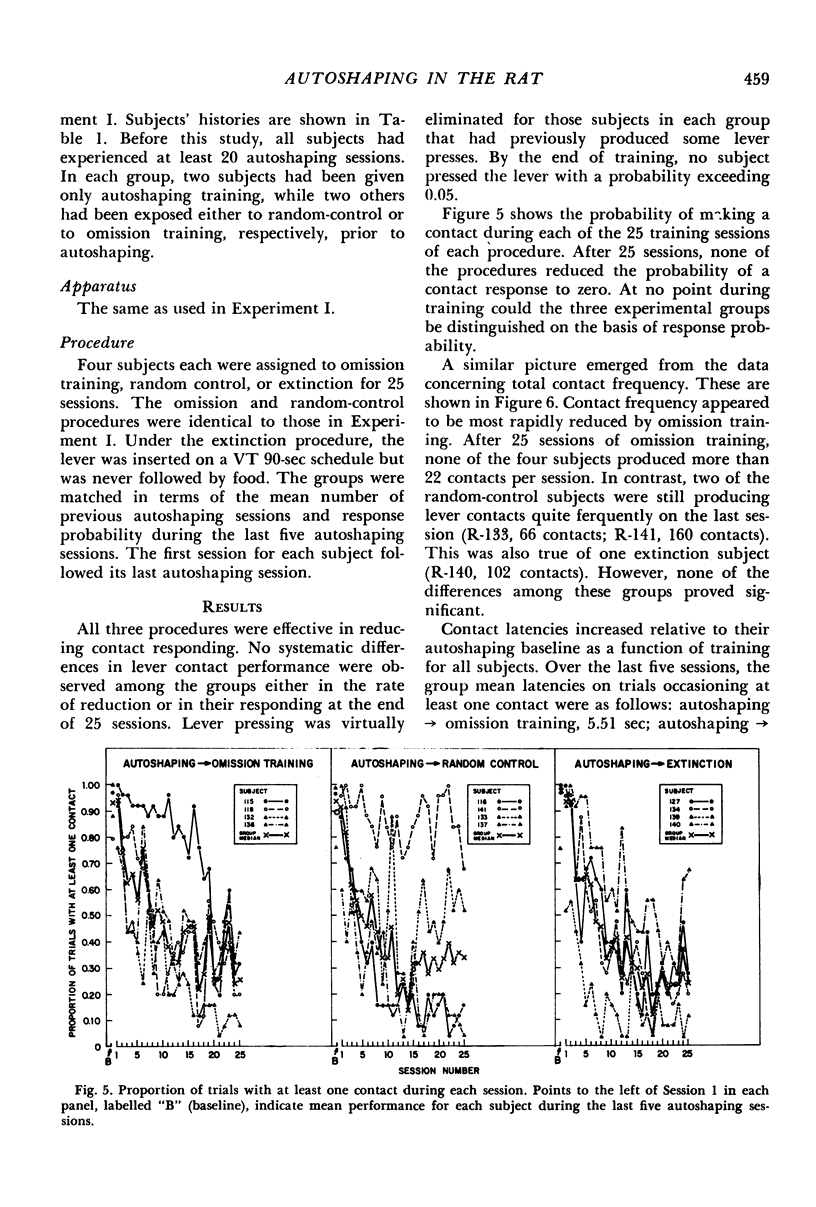

The role of the stimulus-reinforcer contingency in the development and maintenance of lever contact responding was studied in hooded rats. In Experiment I, three groups of experimentally naive rats were trained either on autoshaping, omission training, or a random-control procedure. Subjects trained by the autoshaping procedure responded more consistently than did either random-control or omission-trained subjects. The probability of at least one lever contact per trial was slightly higher in subjects trained by the omission procedure than by the random-control procedure. However, these differences were not maintained during extended training, nor were they evident in total lever-contact frequencies. When omission and random-control subjects were switched to the autoshaping condition, lever contacts increased in all animals, but a pronounced retardation was observed in omission subjects relative to the random-control subjects. In addition, subjects originally exposed to the random-control procedure, and later switched to autoshaping, acquired more rapidly than naive subjects that were exposed only on the autoshaping procedure. In Experiment II, subjects originally trained by an autoshaping procedure were exposed either to an omission, a random-control, or an extinction procedure. No differences were observed among the groups either in the rate at which lever contacts decreased or in the frequency of lever contacts at the end of training. These data implicate prior experience in the interpretation of omission-training effects and suggest limitations in the influence of stimulus-reinforcer relations in autoshaping.

Keywords: autoshaping, omission training, random-control training, lever contacts, lever presses, rats

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barrera F. J. Centrifugal selection of signal-directed pecking. J Exp Anal Behav. 1974 Sep;22(2):341–355. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1974.22-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilbrey J., Winokur S. Controls for and constraints on auto-shaping. J Exp Anal Behav. 1973 Nov;20(3):323–332. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1973.20-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. L., Jenkins H. M. Auto-shaping of the pigeon's key-peck. J Exp Anal Behav. 1968 Jan;11(1):1–8. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1968.11-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engberg L. A., Hansen G., Welker R. L., Thomas D. R. Acquisition of Key-Pecking via Autoshaping as a Function of Prior Experience: "Learned Laziness"? Science. 1972 Dec 1;178(4064):1002–1004. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4064.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLESHLER M., HOFFMAN H. S. A progression for generating variable-interval schedules. J Exp Anal Behav. 1962 Oct;5:529–530. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1962.5-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamzu E., Schwam E. Autoshaping and automaintenance of a key-press response in squirrel monkeys. J Exp Anal Behav. 1974 Mar;21(2):361–371. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1974.21-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamzu E., Williams D. R. Classical conditioning of a complex skeletal response. Science. 1971 Mar 5;171(3974):923–925. doi: 10.1126/science.171.3974.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein R. J., Loveland D. H. Food-avoidance in hungry pigeons, and other perplexities. J Exp Anal Behav. 1972 Nov;18(3):369–383. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1972.18-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein R. J. On the law of effect. J Exp Anal Behav. 1970 Mar;13(2):243–266. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1970.13-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh S. R., Navarick D. J., Fantino E. "Automaintenance": the role of reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1974 Jan;21(1):117–124. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1974.21-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson G. B., Ackilt J. E., Frommer G. P., Hearst E. S. Conditioned Approach and Contact Behavior toward Signals for Food or Brain-Stimulation Reinforcement. Science. 1972 Sep 15;177(4053):1009–1011. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4053.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell R. W., Kelly W. Responding under positive and negative response contingencies in pigeons and crows. J Exp Anal Behav. 1976 Mar;25(2):219–225. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1976.25-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla R. A. Pavlovian conditioning and its proper control procedures. Psychol Rev. 1967 Jan;74(1):71–80. doi: 10.1037/h0024109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz B., Williams D. R. The role of the response-reinforcer contingency in negative automaintenance. J Exp Anal Behav. 1972 May;17(3):351–357. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1972.17-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz B., Williams D. R. Two different kinds of key peck in the pigeon: some properties of responses maintained by negative and positive response-reinforcer contingencies. J Exp Anal Behav. 1972 Sep;18(2):201–216. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1972.18-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiers M., Silberberg A. Lever-contact responses in rats: automaintenance with and without a negative response-reinforcer dependency. J Exp Anal Behav. 1974 Nov;22(3):497–506. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1974.22-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Williams H. Auto-maintenance in the pigeon: sustained pecking despite contingent non-reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1969 Jul;12(4):511–520. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1969.12-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]