Abstract

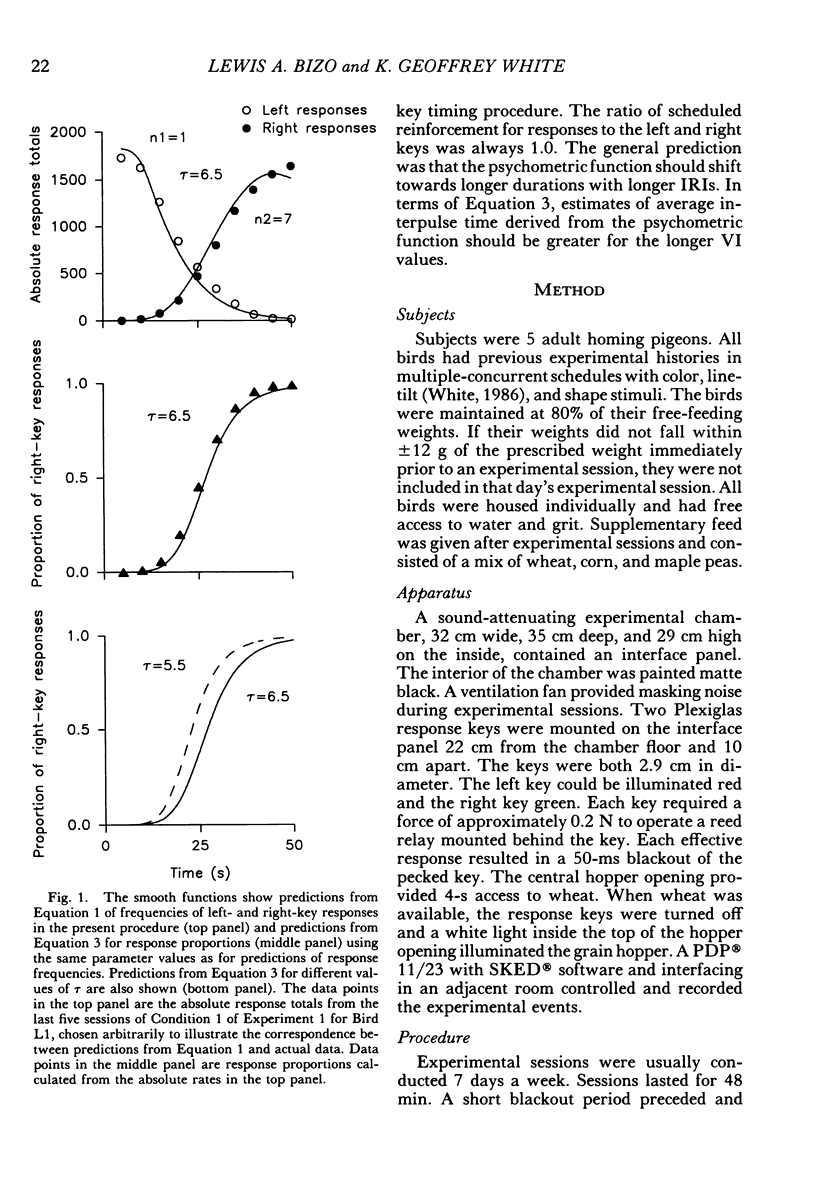

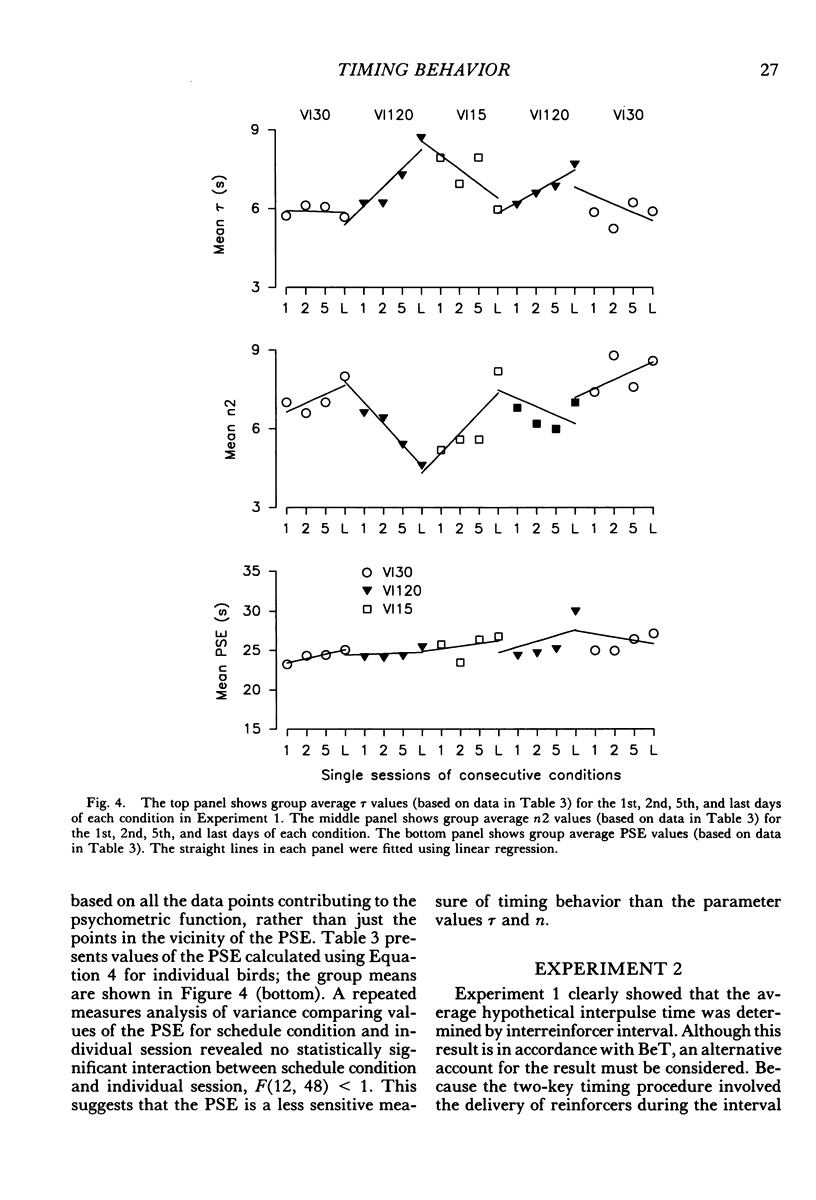

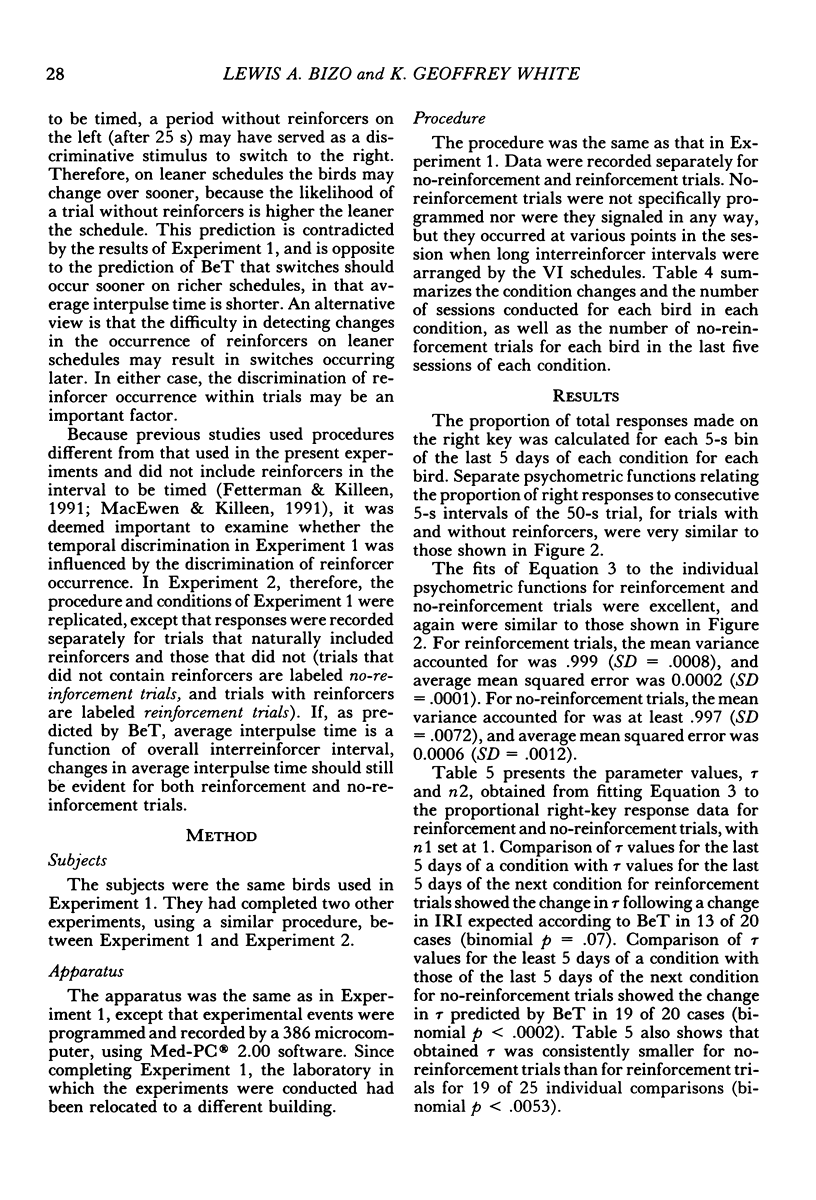

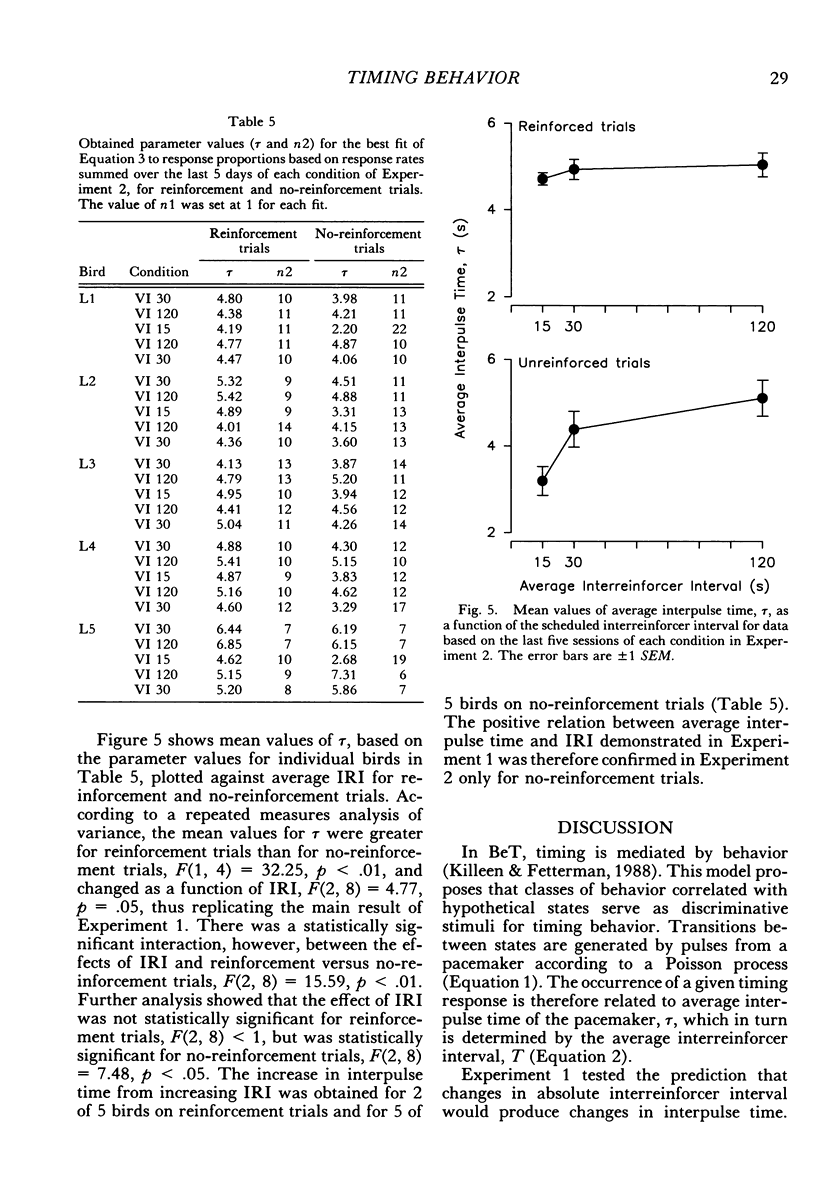

In the behavioral theory of timing, pulses from a hypothetical Poisson pacemaker produce transitions between states that are correlated with adjunctive behavior. The adjunctive behavior serves as a discriminative stimulus for temporal discriminations. The present experiments tested the assumption that the average interpulse time of the pacemaker is proportional to interreinforcer interval. Responses on a left key were reinforced at variable intervals for the first 25 s since the beginning of a 50-s trial, and right-key responses were reinforced at variable intervals during the second 25 s. Psychometric functions relating proportion of right-key responses to time since trial onset, in 5-s intervals across the 50-s trial, were sigmoidal in form. Average interpulse times derived by fitting quantitative predictions from the behavioral theory of timing to obtained psychometric functions decreased when the interreinforcer interval was decreased and increased when the interreinforcer interval was increased, as predicted by the theory. In a second experiment, average interpulse times estimated from trials without reinforcement followed global changes in interreinforcer interval, as predicted by the theory. Changes in temporal discrimination as a function of interreinforcer interval were therefore not influenced by the discrimination of reinforcer occurrence. The present data support the assumption of the behavioral theory of timing that interpulse time is determined by interreinforcer interval.

Keywords: timing, temporal discrimination, behavioral theory of timing, psychometric function, interreinforcer interval, variable-interval schedules, key peck, pigeon

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- FLESHLER M., HOFFMAN H. S. A progression for generating variable-interval schedules. J Exp Anal Behav. 1962 Oct;5:529–530. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1962.5-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen P. R., Fetterman J. G. A behavioral theory of timing. Psychol Rev. 1988 Apr;95(2):274–295. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.95.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen P. R., Fetterman J. G. The behavioral theory of timing: transition analyses. J Exp Anal Behav. 1993 Mar;59(2):411–422. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1993.59-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen P. R., Hanson S. J., Osborne S. R. Arousal: its genesis and manifestation as response rate. Psychol Rev. 1978 Nov;85(6):571–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raslear T. G., Shurtleff D., Simmons L. Intertrial-interval effects on sensitivity (A') and response bias (B") in a temporal discrimination by rats. J Exp Anal Behav. 1992 Nov;58(3):527–535. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1992.58-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs A. The discrimination of stimulus duration by pigeons. J Exp Anal Behav. 1968 May;11(3):223–238. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1968.11-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs D. A. Temporal discrimination and a free-operant psychophysical procedure. J Exp Anal Behav. 1980 Mar;33(2):167–185. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1980.33-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White K. G. Conjoint control of performance in conditional discriminations by successive and simultaneous stimuli. J Exp Anal Behav. 1986 Mar;45(2):161–174. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1986.45-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]