Abstract

The Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3) is expressed in the brush border membrane (BBM) of proximal tubules (PT). Its activity is down-regulated on increases in intracellular cAMP levels. The aim of this study was to investigate the contribution of the protein kinase A (PKA) and the exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (EPAC) dependent pathways in the regulation of NHE3 by adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP). Opossum kidney cells and murine kidney slices were treated with cAMP analogs, which selectively activate either PKA or EPAC. Activation of either pathway resulted in an inhibition of NHE3 activity. The EPAC-induced effect was independent of PKA as indicated by the lack of activation of the kinase and the insensitivity to the PKA inhibitor H89. Both PKA and EPAC inhibited NHE3 activity without inducing changes in the expression of the transporter in BBM. Activation of PKA, but not of EPAC, led to an increase of NHE3 phosphorylation. In contrast, activation of PKA, but not of EPAC, inhibited renal type IIa Na+-coupled inorganic phosphate cotransporter (NaPi-IIa), another Na-dependent transporter expressed in proximal BBM. PKA, but not EPAC, induced the retrieval of NaPi-IIa from BBM. Our results suggest that EPAC activation may represent a previously unrecognized mechanism involved in the cAMP regulation of NHE3, whereas regulation of NaPi-IIa is mediated by PKA but not by EPAC.

Keywords: kidney, transporters

The Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3; SLC9A3) is expressed in the brush border membrane (BBM) of renal proximal tubules (PT) where it plays a major role in acid–base and extracellular volume regulation (1). This transporter is down-regulated by parathyroid hormone (PTH) and dopamine. Acute treatment of rats with PTH (2, 3) or short exposure of opossum kidney (OK) cells to PTH or dopamine (4, 5) inhibits NHE3 activity without reducing its expression in the BBM. The renal type IIa Na+-coupled inorganic phosphate cotransporter (NaPi-IIa; SLC34A1) is also expressed in the BBM of PT where it mediates the bulk of Pi reabsorption from primary urine (6). As NHE3, NaPi-IIa is also down-regulated by PTH and dopamine. In this case, both hormones induce membrane retrieval and lysosomal degradation (refs. 7 and 8; for review, see refs. 9 and 10).

PTH and D1 dopamine receptors couple to G proteins and activate adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP) and diacylglycerol cascades (11, 12). Protein kinase A (PKA) has been regarded as the only effector of cAMP in most eukaryotic cells. However, the effect of cAMP on several cellular functions such as proliferation, gene expression, or activation of PKB and mitogen-activated protein kinases has been shown to be cell-specific, although the molecular mechanisms underlying this specificity are not fully understood. Recently, a new cAMP-dependent signaling pathway, independent of the classic PKA cascade, was discovered. Thus, the guanine exchange factor EPAC (exchange protein directly activated by cAMP) was identified when cAMP-induced activation of the Ras-like small GTPase Rap1 was found to be insensitive to inhibition of PKA (13). Although Rap1 is a substrate for PKA (14), a mutated Rap1 lacking the PKA phosphorylation site is still activated by EPAC in response to cAMP (13). Therefore, the presence of this alternative pathway may help to explain some of the cell-specific cAMP responses.

EPAC1 and the closely related EPAC2 are proteins of 881 and 1,011 residues, respectively (15, 16). They catalyze, in a cAMP-dependent manner, the exchange of GTP for GDP that transforms Rap1 and Rap2 into an activated state (13). EPAC1 and EPAC2 contain, in addition to a cAMP-binding domain and a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) domain for Rap1 and Rap2, a Dishevelled/Egl-10/Pleckstrin domain involved in membrane localization and a Ras-exchanger motif that interacts with the GEF domain (ref. 13; for review, see ref. 16). EPAC 2 contains a second cAMP-binding domain (A domain) at its amino terminus. This A domain binds cAMP with a lower affinity than either the cAMP-binding domain of EPAC1 or the B domain of EPAC2. EPAC1 and the B domain of EPAC2 bind cAMP in vitro with a Km of ≈40 mM, whereas the Km of PKA is ≈1 mM (17). This difference in affinity could be the consequence of differences in key amino acids in the cAMP-binding pocket and has been suggested to allow EPAC to respond to changes in cAMP concentrations in a range in which PKA is already saturated (18). The two isoforms of EPAC show a differential pattern of expression: EPAC1 mRNA has been detected in thyroid, kidney, ovary, skeletal muscle, and specific regions of the brain, whereas EPAC2 expression seems to be restricted to regions of the brain and the adrenal gland (15, 19).

A role of EPAC in several cAMP-regulated processes such as cell adhesion and migration (16), insulin secretion (20, 21), and regulation of the H+/K+-ATPase in the kidney cortical collecting duct (19) has been already demonstrated. Several intracellular cascades may mediate these effects. Thus, EPAC may regulate the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) through activation of the Rap1/B-Raf pathway (19), the PKB (Akt) through an unknown mechanism (22), or the phospholipase Cε through the small GTPase Rap2B (23). Therefore, EPAC may transduce signals to the same downstream effector molecules as PKA.

In this study, we investigated the roles of the PKA and EPAC pathways in the regulation of NHE3 and NaPi-IIa. For that purpose, we took advantage of the availability of cAMP analogs that preferentially activate either pathway (24, 25). OK cells, which endogenously express both transporters, and mouse kidney slices were treated with different cAMP analogs. Their effect on Na-dependent pH recovery (as a measure of NHE3 activity) as well as on Na-dependent Pi uptake (as a measure of NaPi-IIa activity) was analyzed. Inhibition of NHE3 activity was observed with both PKA and EPAC activators. However, down-regulation of NaPi-IIa was observed only with the cAMP analog that preferentially activates PKA. These results suggest that EPAC activation may represent a previously unrecognized mechanism involved in the cAMP regulation of NHE3, whereas regulation of NaPi-IIa is mediated by PKA but not by EPAC.

Results and Discussion

Several studies have proposed roles for EPAC and/or its effector Rap1 in cAMP-induced processes, such as regulation of the H+/K+-ATPase in rat kidney cortical collecting duct cells (19) or insulin secretion by pancreatic islets (20, 21). The aim of this work was to study the contribution of the EPAC- and PKA-dependent pathways to the cAMP-induced inhibition of NHE3 and NaPi-IIa.

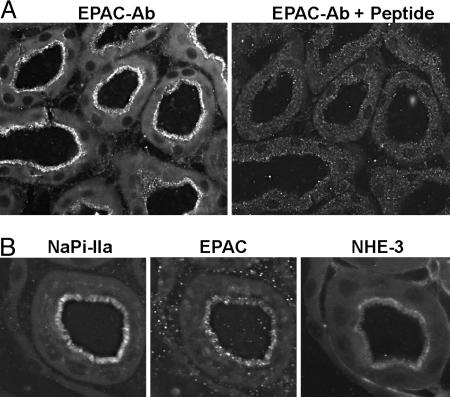

EPAC1 Is Expressed in the BBM of PT. Of the two EPAC isoforms described so far, EPAC1 shows a broader pattern of expression (15), and its mRNA has been detected in several nephron segments (19), whereas the second isoform (EPAC2) seems to have a very restricted tissue distribution (15). RT-PCR on microdissected segments from the rat nephron has shown the expression of EPAC1 and Rap1 mRNAs along the whole nephron. The highest expression of EPAC1 mRNA was found in the glomeruli, proximal convoluted tubules, cortical collecting duct, and outer and inner medullary collecting duct (19). Here, we analyzed the expression of EPAC1 in mouse kidney by using a C-terminal anti-EPAC1 antibody. EPAC1 was detected in S1, S2, and S3 segments of PT, where the signal was concentrated in the BBM (Fig. 1A). The specificity of the staining was demonstrated by peptide protection; preincubation of the antibody with the antigenic peptide fully blocked the fluorescent signal (Fig. 1A). Within the PTs, the strongest staining was found in S2 segments, and the weakest staining was in S3. No signal was detected in glomeruli or distal parts of the nephron (data not shown). The discrepancy between the pattern of expression of EPAC1 mRNA reported in ref. 19 and the protein expression we described here may be due to species-related differences (rat vs. mouse) or may reflect actual differences between mRNA and protein expression. Immunostaining of consecutive sections with the corresponding antibodies indicated that EPAC1 shares a similar pattern of expression as NHE3 and NaPi-IIa, i.e., they are all expressed within the BBM of PTs (Fig. 1B). This common location validates the study of a potential role of EPAC1 in the regulation of both transporters.

Fig. 1.

EPAC1 localization in mouse kidney. (A) EPAC1 staining was attenuated after preincubation of the affinity purified antibody with the antigenic peptide indicating specificity of the applied antiserum. (B) Consecutive cryosections were stained for NaPi-IIa, EPAC, and NHE3. All three proteins were localized in the BBM of proximal tubular cells.

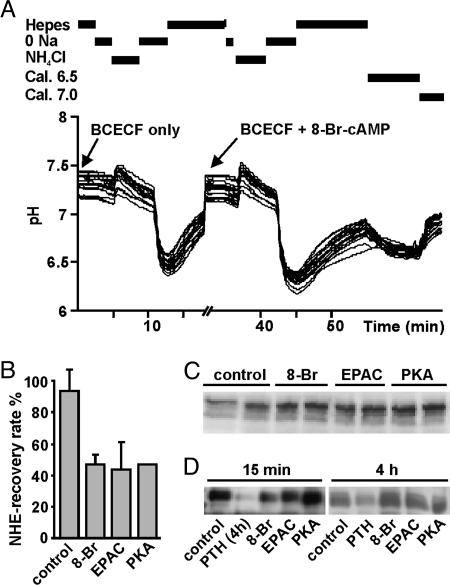

The Activity of NHE3 Is Inhibited via both EPAC and PKA Pathways. Commonly used cAMP analogs, such as 8-Br-cAMP, activate EPAC and PKA equally as well as does cAMP (24, 25). However, analogs modified in the 6′ position of the ribose (6-MB-cAMP) are poor EPAC activators and full PKA activators as compared with cAMP. In contrast, analogs modified in the 2′ position (8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP) induce stronger EPAC activation than cAMP but are only partial agonists for PKA (24, 25). Therefore, we compared the effects of 8-Br-cAMP (EPAC and PKA activator), 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (EPAC activator), and 6-MB-cAMP (PKA I activator) on NHE3 activity. The activity of the exchanger was determined in OK cells (by measurements of intracellular Na-dependent pH recovery rates) as well as in BBM vesicles (BBMV) isolated from slices of mouse kidney cortex (by acridine orange fluorimetry).

The Na-dependent pH recovery rate in OK cells reflects the activity of the endogenous NHE3, because this renal proximal cell line expresses specifically the NHE3 isoform of the Na+/H+ exchanger (26). The recovery rate after the first acidification was taken as 100% for every individual experiment. Fig. 2A shows a scheme of the standard protocol as well as typical pH traces. The pH recovery rate was reduced by ≈50% after a 15-min incubation with 8-Br-cAMP as well as with the EPAC- and PKA-activators (Fig. 2B). The inhibition of NHE3 induced by all cAMP analogs took place without change in the total amount of protein, as determined by Western blot of cell lysates (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, surface biotinylation experiments showed that the inhibition was not mediated by a reduction of the surface-expressed NHE3 (Fig. 2D). As reported in ref. 4, a reduction in surface expression was observed after a 4-h incubation in the presence of PTH (Fig. 2D), indicating that the biotinylation assay is sensitive enough to detect changes in surface-expressed NHE3. The above findings are in agreement with previous reports showing that, in OK cells, acute PTH (4) or dopamine treatment (5) first inhibits NHE3 activity without changing its membrane expression. Only after longer exposure, PTH-induced down-regulation also involved dynamin-dependent endocytosis, suggesting the retrieval of the exchanger via clathrin-coated pits (4). Incubation of OK cells for 4 h with the different analogs did not change the surface-expressed NHE3 (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

NHE3 activity and expression in OK cells. (A) Example of a typical intracellular pH trace. Cells were preincubated with BCECF, followed by a 15-min treatment in the absence or presence of 100 μM 8-Br-cAMP; ≈20 OK cells were monitored per experiment. (B) Effect of the different cAMP analogs on the Na-dependent intracellular pH recovery (NHE activity). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4). (C) Total expression of NHE3. Cells were incubated in duplicate in the absence or presence of 50 μM 8-Br-cAMP, EPAC activator, or PKA activator for 15 min. Cell lysates were processed for Western blot with an anti-NHE3 antibody (n = 3). (D) Surface expression of NHE3. Cells were incubated for 15 min or 4 h in the absence or presence of 50 μM 8-Br-cAMP, EPAC activator, or PKA activator as well as with 10 nM PTH; PTH was always applied for 4 h. Upon biotinylation and streptavidine precipitation, samples were subjected to SDS/PAGE and incubated with an anti-NHE3 antibody (n = 4 and 3, respectively).

The PKA- and EPAC-activators also inhibited the NHE activity in BBMV isolated from slices of mouse kidney cortex. Fig. 3A shows a superposition of original acridine orange fluorescence traces obtained with BBMV isolated from slices incubated in the absence or presence of the PKA activator. Incubation with either analog induced a concentration-dependent inhibition of NHE activity (Fig. 3B). These results demonstrate that NHE3 is inhibited by PKA and EPAC, suggesting that the cAMP-induced inhibition of NHE3 may be mediated via both pathways.

Fig. 3.

NHE3 and PKA activities in mouse kidney samples. Kidney slices were incubated for 30 min with the indicated concentrations of EPAC and PKA activators. Homogenates and BBMV were then prepared and the NHE and PKA activities were measured as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Reproduction showing a superposition of original acridine orange fluorescence traces obtained with BBMV isolated from kidney slices incubated in the absence or presence of PKA activator. (B) Concentration response of both activators over a range of 10–100 μM. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of (n = 4). (C) Determination of PKA activity in homogenates isolated from kidney cortex slices incubated in the absence or presence of 50 μM of the PKA and EPAC activators (n = 3). (D) Western blot with an anti-PKA-substrate antibody of BBMV incubated in the absence or presence of 50 μM PKA or EPAC activator. Substrates phosphorylated on PKA treatment are indicated by arrows. (E) Effect of H89 on the PKA- and EPAC-dependent NHE inhibition. Kidney slices were incubated in the absence or presence of 50 μM H89 for 5 min, before addition of 50 μM PKA or EPAC activators (n = 4). (F) Effect of incubation with 50 μM EPAC and/or PKA activator. (G) Effect of PD098059 on the PKA- and EPAC-dependent NHE inhibition. Kidney slices were incubated in the absence or presence of 20 μM PD098059 for 5 min, before addition of 50 μM PKA or EPAC activators (n = 3).

Next, we analyzed the specificity of the cAMP analogs regarding their ability to activate PKA in kidney slices. Homogenates from slices incubated with 50 μM PKA activator led to an increase in the phosphorylation of an exogenous PKA substrate, as compared with nontreated samples (Fig. 3C). However, homogenates from slices incubated with 50 μM EPAC-activating analog did not induce phosphorylation over basal levels (Fig. 3C). Preincubation with the PKA inhibitor H89 reduced the basal PKA activity in homogenates and blunted the phosphorylation promoted by the PKA activator (data not shown). These results show that incubation with 50 μM PKA, but not with the EPAC, activator results in the enzymatic activation of PKA. In agreement with this data, a Western blot with an anti-PKA substrate antibody indicated that incubation of BBMV with 50 μM PKA activator led to phosphorylation of several PKA substrates (Fig. 3D), whereas incubation with 50 μM EPAC activator did not result in such PKA-dependent phosphorylation.

It has been previously reported that H89 fully or partially prevented the NHE inhibition induced by 8-Br-cAMP or by factors that increase intracellular cAMP levels (5, 26–29). Therefore, we analyzed the effect of H89 on the PKA- and EPAC-dependent inhibitions. Incubation of kidney slices with 50 mM H89 fully abolished the NHE inhibitory effect induced by 50 μM PKA activator (Fig. 3E). However, the inhibition generated by 50 μM EPAC-activator was similar in the absence or presence of H89. This finding, together with the PKA activation shown in Fig. 3C, indicates that the effect of 50 μM EPAC on the NHE activity is specific and does not reflect crossactivation of PKA. Thus, the previously reported observations that H89 blocks the inhibition generated by 8-Br-cAMP probably reflects the reduced ability of this analog to activate EPAC, as compared with 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP. However, it should be noted that the specificity of the cAMP analogs with regard to PKA activation was lost upon incubation at higher concentrations. Thus, at 100 μM, both analogs stimulated PKA activity in kidney homogenates and in both cases the inhibitory effect on NHE was partially prevented by H89 (see Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

PKA and EPAC may regulate cAMP signaling either in an opposite way or synergistically. Thus, in HEK cells PKB is activated upon transfection with EPAC, whereas stimulation of PKA inhibits PKB activity (22). These opposite effects of EPAC and PKA may provide a molecular mechanism for the cell-specific effects of cAMP. In contrast, PKA and EPAC act synergistically to promote neurite extensions in PC-12 cells (25). We found that simultaneous activation of both pathways does not have any additive effect on NHE3 inhibition (Fig. 3F), suggesting that PKA and EPAC may compete for common downstream effectors. Activation of MEK1/2 and the downstream kinases ERK1/2 is responsible for the cAMP stimulation of H+,K+-ATPase in kidney cells, an effect attributed to EPAC (19). Therefore, we study the impact of the MEK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 on the PKA- and EPAC-induced inhibition of NHE. Incubation of kidney slices with 20 mM PD98059 partially prevented the PKA effect, whereas it fully blocked the inhibition generated by the EPAC activator (Fig. 3G). These data suggest that MEK1/2 is a common effector of both pathways with regard to NHE inhibition, although PKA also signals through some additional intracellular cascade to achieve its full effect. We could not observe changes in the phosphorylation state of ERK1/2 upon activation of either pathway (data not shown). The MEK family members are considered among the most selective kinases, and they must be examined to reconcile the full/partial inhibition generated by PD98059 with the lack of ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

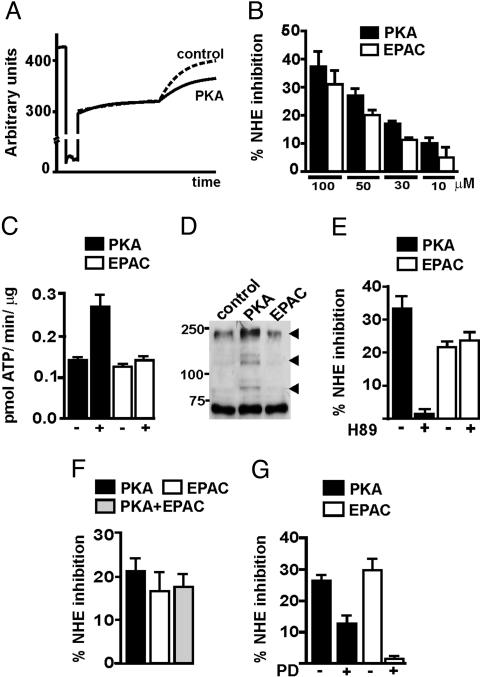

To study whether the PKA- and EPAC-induced inhibition of NHE in kidney was due to changes in the amount of the exchanger, kidney slices were processed for Western blots and immunostaining with anti-NHE3 antibodies. Western blots of BBM indicated that PKA and EPAC stimulation do not change the total amount of NHE3 (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the pattern of expression of the exchanger in the BBM remained unaffected upon incubation with the different agonists (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that the inhibition of NHE induced by PKA and EPAC is not mediated by a reduction of NHE3 in the BBM. This finding is in agreement with previous reports showing that, in rats, acute PTH-induced inhibition of NHE3 does not involve endocytosis of the exchanger (2, 3). Thus, exposure to PTH for 1 h led to a redistribution of NHE3 from the tips to the base of the PT microvilli; however, NHE3 was never detected in AP-2 or horseradish peroxidase positive compartments, indicating the absence of endocytosis (3). Moreover, in parathy-roidectomized rats, acute i.v. bolus of PTH first inhibited NHE3 in the absence of changes on BBM expression, whereas a decrease in surface expression was observed only 4–12 h after the PTH bolus (2).

Fig. 4.

Expression of NHE3 in mouse BBMV. Kidney slices were incubated for 30 min with the indicated analogs (50 μM). (A) Western blot of BBMV with an anti-NHE3 antibody. BBMV isolated from four independent experiments were processed in parallel. (B) Immunofluorescence of kidney slices with anti-NHE3 antibodies (green) as well as with phalloidin (red).

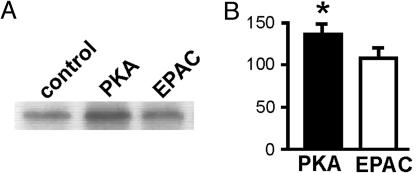

In OK cells, PTH-induced inhibition of NHE3 activity was shown to proceed in parallel with phosphorylation of the transporter (4). This PTH-dependent phosphorylation was prevented by PKA inhibitors. Therefore, we next studied the effect of the PKA- and EPAC-activating analogs on the state of phosphorylation of NHE3 in OK cells. As shown in Fig. 5A, NHE3 is constitutively phosphorylated. Collazo et al. (4) have shown that this basal phosphorylation takes place mostly on serine residues. Incubation with the PKA-activating analog induced an increase in phosphorylation, whereas activation of EPAC had no effect (Fig. 5 A and B). These results suggest that, unlike the PKA effect, the EPAC-induced inhibition of NHE3 is independent of phosphorylation of the transporter.

Fig. 5.

Phosphorylation of NHE3 in OK cells. Confluent cultures were phosphorylated and NHE3 was immunoprecipitated as described. (A) Typical autoradiography. (B) Quantification of seven independent experiments. The signal detected in untreated samples was taken as 100% for each experiment.

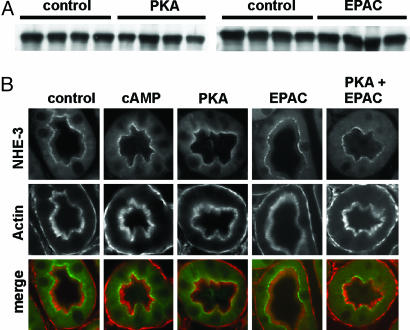

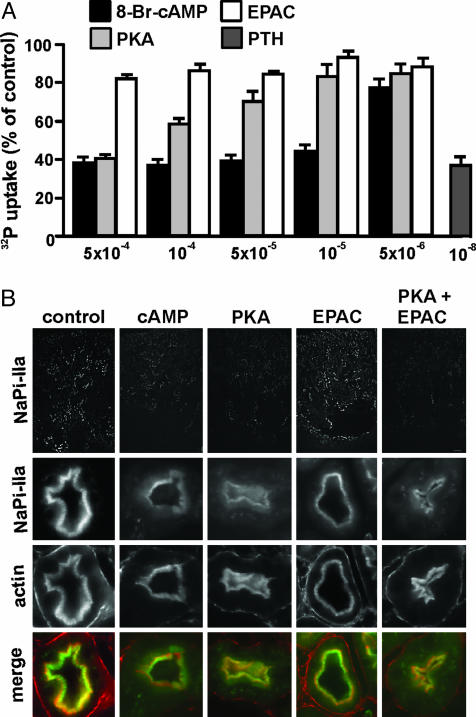

The Activity of NaPi-IIa Is Inhibited by PKA but Not EPAC. As for NHE3, the cAMP-induced down-regulation of NaPi-IIa is well documented. Most studies have been done in the context of PTH signaling and suggest a preferential implication of cAMP upon activation of basolateral PTH receptors (30). With few exceptions, information gathered so far suggests that PTH inhibits NaPi-IIa by promoting endocytosis and degradation of the cotransporter (7). Recently, we have also shown that activation of apical, but not basolateral, D1-like dopamine receptors induces NaPi-IIa internalization, by a mechanism dependent on PKA but independent of PKC (8). To study the contribution of the PKA- and EPAC-dependent pathways in the regulation of NaPi-IIa, we performed 32P uptakes in OK cells treated for 4 h in the presence of several concentrations of the cAMP analogs. OK cells are known to express a NaPi-IIa cotransporter that is regulated by the major factors that regulate the cotransporter in the kidney (31, 32). As shown in Fig. 6A, the Na-dependent 32P uptake was inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner by 8-Br-cAMP as well as by the PKA-activating analog. The highest tested concentration of both analogs (5 × 10–4 M) induced a reduction in uptake similar to that induced by 10–8 M PTH; this concentration of PTH is known to lead to maximal inhibition of NaPi-IIa in OK cells. However, the Na-dependent 32P uptake was not affected upon incubation of OK cells with the EPAC-activating analog (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, incubation with submaximal concentrations of the PKA-activating analog together with the EPAC-specific activator did not result in a stimulation of the former one (data not shown). These findings suggest that cAMP inhibits NaPi-IIa by activating the PKA-dependent pathway, whereas the EPAC-dependent signaling is not involved in this process. We and others (3, 7, 8, 30) have reported that PTH- and dopamine-induced inhibition of NaPi-IIa occurs as a consequence of membrane retrieval followed by lysosomal degradation of the cotransporter. Therefore, we analyzed the pattern of expression of NaPi-IIa in kidney slices upon incubation with the different cAMP analogs. As shown in Fig. 6B, incubation with 8-Br-cAMP or with the PKA-specific activator, induced internalization of NaPi-IIa, as indicated by the reduction of the immunosignal in BBM, whereas the EPAC-activator had no effect. Therefore, these results suggest that cAMP-induced down-regulation of NaPi-IIa involves the PKA-dependent pathway but not the EPAC-dependent pathway.

Fig. 6.

NaPi-IIa activity and expression. (A) Na-dependent 32P-uptake. Cells were incubated for 4 h in the absence or presence of 10 nM PTH (1–34) or the indicated concentrations of the cAMP analogs. (B) Kidney slices were incubated in the absence or presence of 50 μM indicated analogs and processed for immunofluorescence with anti-NaPi-IIa antibodies (green) and phalloidin (red). Rectangles show an overview of NaPi-IIa signal; squares are magnified images.

In summary, we have shown the following: (i) EPAC1 is expressed in mouse PT and colocalizes with NHE3 and NaPi-IIa in BBM; (ii) activation of PKA or EPAC inhibits the activity of NHE3, whereas PKA, but not EPAC, induces inhibition of NaPi-IIa; (iii) inhibition of NHE3 by PKA and EPAC takes place without changes in the surface expression of the exchanger; and (iv) PKA, but not EPAC, induces an increase in phosphorylation of NHE3. Therefore, further studies are required to clarify the precise molecular mechanism of the EPAC-induced NHE3 inhibition.

Materials and Methods

Kidney Slices, Preparation, and Treatments. Slices (1 mm thick) from mouse kidney were prepared as described in ref. 33. Slices were incubated for 30 min with 200 μM ATP in the absence or presence of 100 μM 8-Br-cAMP and the indicated concentrations of PKA (6-MB-cAMP) and/or EPAC (8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP) activators. Where indicated, samples were preincubated for 10 min with 50 μM PKA inhibitor H89 or 20 μM ERK inhibitor PD098059 before the addition of cAMP analogs. After treatment, slices were processed for either immunohistochemistry or determination of PKA or NHE activities. cAMP analogs were obtained from biolog (Life Science, Arlington Heights, IL), and other chemicals were obtained from Sigma.

Immunohistochemistry on Kidney Slices. Cryosections were incubated with antibodies against NHE3 (1:500; antisera #1568, kindly provided by O. W. Moe, University of Texas, Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas), NaPi-IIa (1:500), or EPAC1 (1:20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as reported in ref. 33. Double staining with β-actin was achieved by adding rhodamine phalloidin (1:50; Molecular Probes) together with the secondary antibodies. To control for the specificity of the anti-EPAC immunostaining, the antiserum was incubated overnight at 4°C with the synthetic antigenic peptide (10 mg/ml) before application.

Determination of PKA and NHE Activities. Homogenates and BBMV from mouse kidney slices were prepared as reported in ref. 34. Subsequently, protein was measured by using a protein determination kit (Bio-Rad), and the final concentration was adjusted to 4 and 10 mg/ml, respectively.

PKA activity was determined by using the SignaTECT PKA assay system (Promega). Homogenate samples (20 μg) were incubated for 5 min at 30°C with a biotinylated PKA-substrate in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP (Hartmann Analytic, Braunschweig, Germany). Then the 32P-labeled substrate was purified by using the Biotin Capture Membranes provided by the kit. After extensive washes, the incorporation of 32P was measured.

NHE activity was determined in BBMV by the acridine orange technique as described in ref. 35. Measurements were performed in a Shimadzu RF-5000 spectrofluometer equipped with a thermostatized cuvette (kept at 25°C). BBMVs were dissolved in a buffer containing 280 mM mannitol, 5 mM Mes, and 2 mM MgCl2 (adjusted to pH 5.5 with N-methyl-d-glucamine). Acridine orange was excited at 493 nm, and emission was monitored at 530 nm. The cuvette was filled with 2 ml of buffer (240 mM mannitol/20 mM Hepes/2 mM MgCl2, adjusted to pH 7.5 with N-methyl-d-glucamine), containing 6 μM acridine orange. The experiment was started by injecting 30 μl of BBMV suspension. After 60 s of equilibration, NHE activity was initiated by injection of 80 μl of 2 M Na gluconate. NHE activity was calculated as ratio of ΔpH per min over Q, where Q is the initial quenching after injection of BBMV. All experiments were done at least in quadruplicates and repeated four times with BBMV from two animals per experiment.

Cell Culture. OK cells (clone 3B/2) were grown in DMEM/Ham's F-12 medium (1:1) supplemented with 10% FCS, 20 mM Hepes, and 2 mM l-glutamine as described in ref. 31. Cell culture supplies were obtained from GIBCO/BRL.

Isotope Flux (32P Uptakes). Confluent OK cells plated on 12-well plates were incubated for 4 h with either 10 nM PTH (bovine synthetic fragment 1–34; Sigma), or the indicated concentrations of cAMP analogs. Uptakes were performed by incubating the cells for 10 min in the presence of 0.25–0.5 μCi (1 Ci = 37 GBq) of 32P per ml (Hartmann Analytic) as described in detail in ref. 36.

Intracellular pH Measurements. OK cells were grown to subconfluency on glass slides. Individual slides were transferred to a heated perfusion chamber maintained at 37°C on an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 200) and attached to a free-flow perfusion system. All solutions were kept at 37°C by using a feedback heating system. After mounting, cells were incubated for 15 min at 37°C with a standard Hepes solution containing 10 μM pH-sensitive dye 2′-7′-bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (Molecular Probes). Cells were then washed with Hepes to remove any non-deesterified dye. After washing, cells were excited with 490 and 440 nm light, while the emission was monitored at 535 nm. The ratiometric emission of 490/440 was converted to intracellular pH after calibration (37) by using the high K+/nigericin technique (38, 39). In brief, after a 20 mM NH4Cl prepulse, cells were washed with a Na-free solution (Hepes buffer with NaCl replaced by of N-methyl-d-glucamine). NHE3 activity was calculated from the initial slope of intracellular alkalinization upon readdition of Na. To allow for direct comparison, ΔpH per min was calculated only for intracellular pH values in the range of pH 6.50–6.80. All experiments were performed as paired experiments with measurement of NHE3 activity before and after a 15-min period of incubation of cells with the indicated analog. Control cells were incubated only with standard Hepes solution.

OK Cell Lysate Preparation and Western Blotting. Confluent cultures were incubated with cAMP analogs (50 μM) or PTH (10 nM) for 4 h. Cells were lysed in Tris-buffered saline containing Igepal (1:200) and protease inhibitor mixture (1:100), and centrifuged at 5,000 × g at 4°C for 5 min. The supernatants were removed, and their protein concentration was determined. About 50 μg was subjected to SDS/PAGE. Nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schüll) were incubated overnight at 4°C with a polyclonal antibody against NHE3 (1:1,000; kindly provided by O. W. Moe) (4). Upon incubation with HRP-linked secondary antibodies, immunoreactive signals were detected by chemiluminiscence (ECL, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Biotinylation. OK cells grown in 10-cm plates were incubated for 15 min or 4 h with cAMP analogs (50 μM). Then, surface-expressed proteins were biotinylated for 1 hr with sulfo-LC-NHS-Biotin [sulfo-Succinimidyl-6-(biotinamido)hexanoate; 1.5 mg/ml; Pierce] as reported in ref. 4. After incubation with 100 mM glycin, cells were lysated in RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl/5 mM EDTA/50 mM Tris/1% Triton X-100/0.5% Na-deoxycholate/0.1% SDS/5 μg/ml leupeptin/5 μg/ml pepstatin A). Lysates were centrifugated at 2,500 × g at 4°C for 25 min, and the supernatants were incubated overnight with 50 μl of prewashed streptavidin beads (Pierce). After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 20 s, the pellets were washed sequentially with buffer A (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4/100 mM NaCl/5 mM EDTA), buffer B (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4/500 mM NaCl), and buffer C (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4). Proteins were eluted by addition of 30 μl of 2× loading buffer (containing 60 μg/μl DTT) and incubation at 95°C for 3 min. After centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 min, supernatants were loaded on SDS/PAGE, and Western blotting was performed with NHE3 antibodies.

NHE3 Phosphorylation. OK cells were plated in 10-cm plates, grown to confluency, and serum-starved overnight before phosphorylation experiments. Upon incubation for 1 h in phosphate-free media, cells were pulsed with 32P orthophosphate (300 mCi/ml) for 2 h. Then, cultures were incubated for 30 min in the presence/absence of 50 μM PKA- and EPAC-activating analogs. Cells were lysed in a buffer containing 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM EGTA, and 0.5 mM DTT, plus 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1% protease inhibitor mixture, and 1% phosphatase inhibitor mixture. NHE3 was immunoprecipitated according to ref. 4. Immunoprecipitated material was then eluted by addition of 1× loading buffer containing 1% 2-mercaptoethanol. Eluted samples were separated into a 9% SDS/PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Incorporated 32P was detected by autoradiography.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Gasser for professional assistance in preparing the figures and Dr. O. W. Moe for kindly providing the polyclonal antibody against NHE3. This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation Grants 31-65397.01 (to H.M.) and 31-068318 (to C.A.W.), the Stiftung für Wissenschaftliche Forschung der Universität Zürich, and the Sixth European Frame Work EureGene Project (005085) (to C.A.W. and H.M.).

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: BBM, brush border membrane; BBMV, BBM vesicles; EPAC, exchange protein directly activated by cAMP; NaPi-IIa, Na+/phosphate cotransporter type IIa; NHE3, Na+/H+-exchanger isoform 3; OK, opossum kidney; PT, proximal tubules; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

References

- 1.Schultheis, P. J., Clarke, L. L., Meneton, P., Miller, M. L., Soleimani, M., Gawenis, L. R., Riddle, T. M., Duffy, J. J., Doetschman, T., Wang, T., et al. (1998) Nat. Genet. 19, 282–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan, L., Wiederkehr, M. R., Collazo, R., Wang, H., Crowder, L. A. & Moe, O. W. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 11289–11295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang, L. E., Maunsbach, A. B., Leong, P. K. & McDonough, A. A. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. 287, F896–F906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collazo, R., Fan, L., Hu, M. C., Zhao, H., Wiederkehr, M. R. & Moe, O. W. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 31601–31608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiederkehr, M. R., Di Sole, F., Collazo, R., Quinones, H., Fan, L., Murer, H., Helmle-Kolb, C. & Moe, O. W. (2001) Kidney Int. 59, 197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck, L., Karaplis, A. C., Amizuka, N., Hewson, A. S., Ozawa, H. & Tenenhouse, H. S. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 5372–5377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lotscher, M., Kaissling, B., Biber, J., Murer, H., Kempson, S. A. & Levi, M. (1996) Kidney Int. 49, 1010–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bacic, D., Capuano, P., Baum, M., Zhang, J., Stange, G., Biber, J., Kaissling, B., Moe, O. W., Wagner, C. A. & Murer, H. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. 288, F740–F747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murer, H., Hernando, N., Forster, I. & Biber, J. (2000) Physiol. Rev. 80, 1373–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murer, H., Forster, I. & Biber, J. (2004) Pflügers Arch. 447, 763–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abou-Samra, A. B., Juppner, H., Force, T., Freeman, M. W., Kong, X. F., Schipani, E., Urena, P., Richards, J., Bonventre, J. V., Potts, J. T., Jr., et al. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 2732–2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felder, C. C., McKelvey, A. M., Gitler, M. S., Eisner, G. M. & Jose, P. A. (1989) Kidney Int. 36, 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Rooij, J., Zwartkruis, F. J., Verheijen, M. H., Cool, R. H., Nijman, S. M., Wittinghofer, A. & Bos, J. L. (1998) Nature 396, 474–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quilliam, L. A., Mueller, H., Bohl, B. P., Prossnitz, V., Sklar, L. A., Der, C. J. & Bokoch, G. M. (1991) J. Immunol. 147, 1628–1635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawasaki, H., Springett, G. M., Mochizuki, N., Toki, S., Nakaya, M., Matsuda, M., Housman, D. E. & Graybiel, A. M. (1998) Science 282, 2275–2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bos, J. L. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 733–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Rooij, J., Rehmann, H., van Triest, M., Cool, R. H., Wittinghofer, A. & Bos, J. L. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 20829–20836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Springett, G. M., Kawasaki, H. & Spriggs, D. R. (2004) BioEssays 26, 730–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laroche-Joubert, N., Marsy, S., Michelet, S., Imbert-Teboul, M. & Doucet, A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18598–18604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakazaki, M., Crane, A., Hu, M., Seghers, V., Ullrich, S., Aguilar-Bryan, L. & Bryan, J. (2002) Diabetes 51, 3440–3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang, G., Joseph, J. W., Chepurny, O. G., Monaco, M., Wheeler, M. B., Bos, J. L., Schwede, F., Genieser, H. G. & Holz, G. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8279–8285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mei, F. C., Qiao, J., Tsygankova, O. M., Meinkoth, J. L., Quilliam, L. A. & Cheng, X. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 11497–11504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt, M., Evellin, S., Weernink, P. A., von Dorp, F., Rehmann, H., Lomasney, J. W. & Jakobs, K. H. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 1020–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enserink, J. M., Christensen, A. E., de Rooij, J., van Triest, M., Schwede, F., Genieser, H. G., Doskeland, S. O., Blank, J. L. & Bos, J. L. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 901–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christensen, A. E., Selheim, F., de Rooij, J., Dremier, S., Schwede, F., Dao, K. K., Martinez, A., Maenhaut, C., Bos, J. L., Genieser, H. G. & Doskeland, S. O. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 35394–35402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azarani, A., Goltzman, D. & Orlowski, J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 20004–20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Felder, C. C., Campbell, T., Albrecht, F. & Jose, P. A. (1990) Am. J. Physiol. 259, F297–F303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Sole, F., Casavola, V., Mastroberardino, L., Verrey, F., Moe, O. W., Burckhardt, G., Murer, H. & Helmle-Kolb, C. (1999) J. Physiol. (London) 515, 829–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pedrosa, R., Gomes, P. & Soares-da-Silva, P. (2004) Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 14, 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Traebert, M., Volkl, H., Biber, J., Murer, H. & Kaissling, B. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. 278, F792–F798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfister, M. F., Lederer, E., Forgo, J., Ziegler, U., Lotscher, M., Quabius, E. S., Biber, J. & Murer, H. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 20125–20130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pfister, M. F., Hilfiker, H., Forgo, J., Lederer, E., Biber, J. & Murer, H. (1998) Pflügers Arch. 435, 713–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bacic, D., Schulz, N., Biber, J., Kaissling, B., Murer, H. & Wagner, C. A. (2003) Pflügers Arch. 446, 52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biber, J., Stieger, B., Haase, W. & Murer, H. (1981) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 647, 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cassano, G., Stieger, B. & Murer, H. (1984) Pflügers Arch. 400, 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sorribas, V., Markovich, D., Verri, T., Biber, J. & Murer, H. (1995) Pflügers Arch. 431, 266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas, J. A., Buchsbaum, R. N., Zimniak, A. & Racker, E. (1979) Biochemistry 18, 2210–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roos, A. & Boron, W. F. (1981) Physiol. Rev. 61, 296–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winter, C., Schulz, N., Giebisch, G., Geibel, J. P. & Wagner, C. A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 2636–2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.