Abstract

Lymphoid lineage-committed progenitors, such as common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs), maintain a latent myeloid differentiation potential, which can be initiated by stimulation through exogenously expressed cytokine receptors, including IL-2 receptors. Here we show that the transcription factor CCAAT enhancer-binding protein-α (C/EBPα) is promptly up-regulated in CLPs upon ectopic IL-2 stimulation. Enforced C/EBPα expression is sufficient to initiate myeloid differentiation from CLPs, as well as from proT and proB cells, even though proB cells do not give rise to myeloid cells after ectopic IL-2 stimulation. Expression of Pax5, a B lymphoid-affiliated transcription factor, is completely suppressed by enforced C/EBPα but not by ectopic IL-2 stimulation in proB cells. Introduction of Pax5 blocks ectopic IL-2 receptor-mediated myeloid lineage conversion in CLPs. These data suggest that C/EBPα is a proximal target of cytokine-induced lineage conversion in lymphoid progenitors. Furthermore, complete loss of Pax5 expression triggered by up-regulation of C/EBPα is a critical event for lineage conversion from lymphoid to myeloid lineage in CLPs and proB cells.

Keywords: commitment, cytokine receptor signaling, hematopoiesis, lineage instruction, transcription factor

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) maintain multipotent differentiation potential and continuously generate all types of blood cells throughout adult hematopoiesis (1). During the early phase of differentiation, HSCs, or downstream multipotent hematopoietic progenitors, need to commit to either the lymphoid or myeloid lineage, the two major branches of hematopoiesis (1). Lymphoid and myeloid lineage commitment is demonstrated through the identification of lineage-restricted progenitors downstream of HSCs (2). Common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) give rise exclusively to all classes of lymphocytes at the clonal level, whereas the developmental potential of most common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) is restricted to the myeloid lineage (3, 4). Lymphoid and myeloid lineage commitment, however, may not occur at the same progenitor stage. Recent studies suggest that, on the course of lymphocyte development, multipotent progenitors (MPPs) first lose erythroid differentiation potential, followed by the loss of granulocyte/macrophage (GM) lineage differentiation potential (5, 6). The mechanisms of how lymphoid or myeloid lineage decision is made in HSCs or MPPs remain to be clarified.

Recent studies demonstrated that cytokines can have instructive actions during different stages of hematopoiesis by regulating expression levels of transcription factors. For example, GM–colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) was shown to direct macrophage vs. neutrophil outcome in myeloid progenitors by regulating the CCAAT enhancer-binding protein-α (C/EBPα) and PU.1 expression levels (7). IL-7 was also demonstrated to up-regulate early B cell factor (EBF) expression level in pre-proB cell and promote transition to proB cell stage during B cell development (8). Nonetheless, it is not clear whether cytokines are involved in determining lymphoid vs. myeloid lineage decision in more primitive progenitors.

Stimulation through ectopic cytokine receptors, such as IL-2 and GM-CSF receptors, uncovers a latent myeloid differentiation potential in CLPs and proT (DN1 and DN2) cells (9–11). Although using an artificial system, IL-2-induced lineage conversion in CLPs is a clear evidence demonstrating that cytokines can have instructive actions in determining lymphoid vs. myeloid lineage outcome (12).

The lineage conversion from lymphoid to myeloid lineage described above is striking, but mechanisms of how IL-2 receptor (IL-2R) signaling triggers the latent myeloid differentiation potential in lymphoid progenitors have not been elucidated. Although CLPs can differentiate into erythroid lineage cells upon introduction of GATA-1 (13), ectopic IL-2R signaling induces only GM lineage cells from CLPs (9). Because CLPs do not express any myeloid-related genes (4, 9, 14), one may assume that key transcription factors for GM cell development (15, 16) are up-regulated in CLPs upon initiation of lineage conversion by exogenous IL-2R signaling. One such candidate transcription factor is C/EBPα, which plays a critical role during development of GM lineage cells (7, 17–20).

In this study, we investigated the role of C/EBPα in lineage conversion of lymphoid progenitors triggered by IL-2R signaling. We found that, in addition to up-regulation of myeloid-related genes, silencing of Pax5, a lymphoid-specific transcription factor, was also necessary for lineage conversion to occur. We demonstrated a possible antagonistic effect of C/EBPα and Pax5 for myeloid or lymphoid lineage choice in CLPs.

Results

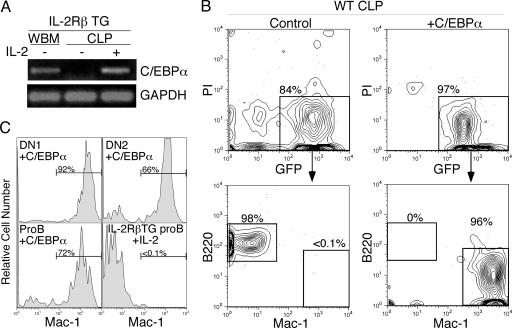

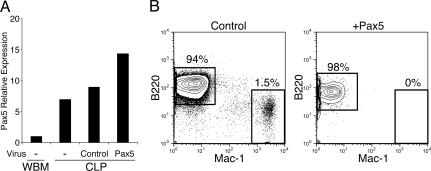

C/EBPα Is a Major Component to Initiate GM Differentiation from Lymphoid Progenitors. CLPs do not express any myeloid-related genes under normal developmental conditions (4, 9, 14). Therefore, we reasoned that myeloid-affiliated gene(s), especially transcription factors that are involved in GM cell development, may be up-regulated immediately in IL-2RβTG CLPs after IL-2 stimulation. Gene profiling of IL-2-stimulated IL-2RβTG CLPs showed that C/EBPα is up-regulated as early as 24 h after IL-2 stimulation (Fig. 1A). To clarify the causative relationship between C/EBPα expression and myeloid cell differentiation from CLPs, we introduced C/EBPα, using a retroviral system into WT CLPs. As shown in Fig. 1B, control GFP+ CLPs differentiated into B220+ B cells on OP9 stromal cell layers. In contrast, C/EBPα+ CLPs gave rise exclusively to Mac-1+ myeloid cells, suggesting that introduction of C/EBPα is sufficient to convert the cell fate of CLPs from lymphoid to myeloid lineage. These C/EBPα+ CLPs also formed GM colonies on methylcellulose culture at ≈10% plating efficiency (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Ectopic C/EBPα expression induces GM lineage differentiation from lymphoid progenitors. (A) Up-regulation of C/EBPα in IL-2RβTG CLPs at 24 h after IL-2 stimulation. IL-2RβTG CLPs were stimulated with or without 50 ng/ml human IL-2 for 24 h and subjected to RT-PCR analysis. Whole bone marrow cells (WBM) were used as positive control. GAPDH was amplified for cDNA loading control. (B) Introduction of C/EBPα initiates GM cell differentiation in CLPs. WT CLPs were infected with either control empty or C/EBPα retroviruses, as described in Material and Methods. After infection, GFP+ cells were sorted and cultured on OP9 stromal cell layers in the presence of IL-3 and GM-CSF for 3–5 days. B220+ B cell and Mac-1+ myeloid cell readout was assessed by FACS. (C) Ectopic C/EBPα expression triggers myeloid cell differentiation in proT and proB cells. C/EBPα was introduced in WT proT and proB cells by retroviral system. GFP+ ectopic C/EBPα-positive cells were cultured on OP9 stromal cell layers in the presence of IL-3 and GM-CSF. We also cultured IL-2RβTG proB cells on OP9 cells in the presence of human IL-2 as well as IL-3 and GM-CSF. After 5 days of culture, we determined Mac-1+ myeloid cell readout by FACS.

The effect of C/EBPα in other lymphoid progenitors was further examined. ProT cells are also reported to maintain a latent myeloid differentiation induced by IL-2 stimulation (10). Similar to CLPs, ectopic C/EBPα expression in proT cells (DN1 and DN2 subsets) led to GM cell development (Fig. 1C Upper). Consistent with our previous report (9), we did not observe lineage conversion in IL-2RβTG proB cells upon IL-2 stimulation (Fig. 1C Lower Right) (9). In contrast, introduction of C/EBPα induced myeloid differentiation from proB cells (Fig. 1C Lower Left), as reported by Xie et al. (21).

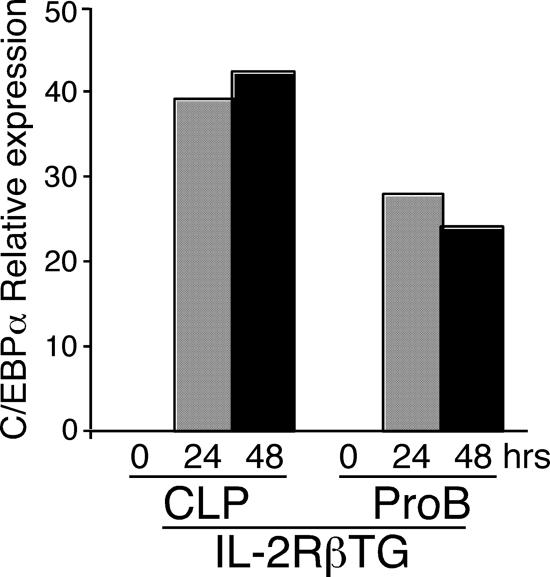

Down-Regulation of Pax5 by C/EBPα in CLPs and ProB Cells. We searched for why this discrepancy in proB cells occurred. We first examined whether C/EBPα is up-regulated in IL-2RβTG proB cells after IL-2 stimulation. As shown in Fig. 2, although at a slightly lower level than in CLPs, C/EBPα up-regulation was observed in IL-2RβTG proB cells upon IL-2 stimulation in the same fashion as in IL-2RβTG CLPs. Because it has been shown that the removal of Pax5 enables proB cells to differentiate into macrophages (22) in the presence of ectopic C/EBPα (22, 23), we hypothesized that Pax5 expression might be critically involved in this lineage conversion in proB cells from lymphoid to myeloid lineage. Therefore, we next examined Pax5 expression in IL-2RβTG CLPs and proB cells after IL-2 stimulation.

Fig. 2.

IL-2RβTG proB cells up-regulate C/EBPα upon IL-2 stimulation in a similar pattern as in IL-2RβTG CLPs. CLPs and proB cells derived from IL-2RβTG mice were sorted and cultured in the presence of human IL-2 as well as SCF, Flt3L, and IL-7. Total RNA was purified from these cells at the indicated time point and subjected to real-time PCR analysis. The expression level of the C/EBPα gene was normalized to GAPDH. In this analysis, C/EBPα expression level in WBM is arbitrary defined as unit 1. The mean value from triplicate samples is shown.

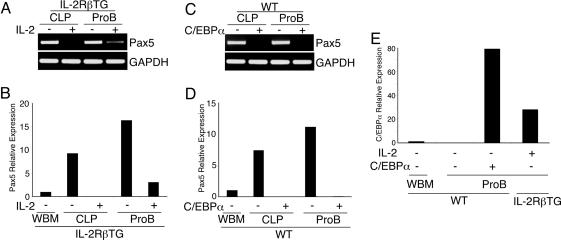

We found that Pax5 expression was significantly down-regulated but still present at a low level in IL-2RβTG proB cells 48 h after IL-2 stimulation, whereas no Pax5 expression was detectable in IL-2RβTG CLPs under the same conditions (Fig. 3 A and B). In contrast, ectopic C/EBPα expression completely blocked Pax5 expression in both CLPs and proB cells (Fig. 3 C and D). These data indicate that complete silencing of Pax5 expression is necessary for myeloid differentiation from CLPs and proB cells. To investigate why different levels of Pax5 repression were observed, we compared C/EBPα expression levels between WT proB cells with ectopic C/EBPα expression and IL-2-stimulated IL-2RβTG proB cells. As shown in Fig. 3E, ectopic C/EBPα expression was ≈2.5-fold higher than C/EBPα expression induced by IL-2 stimulation in IL-2RβTG proB cells. These data suggest that Pax5 expression is promptly down-regulated in the presence of C/EBPα in CLPs and proB cells at the onset of lineage conversion. In addition, C/EBPα may down-regulate Pax5 expression in a dose-dependent manner in CLPs and proB cells.

Fig. 3.

C/EBPα down-regulates Pax5 expression in CLPs and proB cells in a dose-dependent manner. (A) Pax5 expression remains in IL-2RβTG proB cells but not in IL-2RβTG CLPs after IL-2 stimulation. IL-2RβTG CLPs and proB cells were stimulated with IL-2 for 48 h. Pax5 expression was then determined by RT-PCR. Pax5 expression level was further quantified by real-time PCR (B). (C) No Pax5 expression is observed after introduction of C/EBPα in CLPs and proB cells. After introduction of C/EBPα into WT CLPs and proB cells, these cells were further cultured for 24 h at 37°C. Then GFP+ cells were purified by FACS and subjected to RT-PCR analysis. The expression level of Pax5 was further quantified by real-time PCR analysis (D). (E) Comparison of C/EBPα expression levels between IL-2RβTG proB cells stimulated with IL-2 and ectopic C/EBPα+ proB cells by quantitative PCR analysis. The samples used here were prepared as described in A and C. Pax5 and C/EBPα expression levels were normalized with the expression level of each gene in WBM.

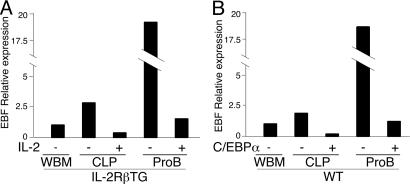

Because the Pax5 gene is a direct target of early B-cell factor (EBF) (24), it is possible that down-regulation of Pax5 is the secondary event after suppression of EBF expression by C/EBPα. As shown in Fig. 4, EBF expression was rapidly down-regulated by either IL-2 stimulation or ectopic C/EBPα expression in both CLP and proB cells. However, although Pax5 expression was completely silenced in ectopic C/EBPα+ CLPs and proB cells, a substantial amount of EBF expression still remained. The existence of residual EBF expression suggests that the down-regulation of Pax5 is not simply a result of suppression of EBF by C/EBPα expression, but other factors may be involved.

Fig. 4.

Down-regulation of EBF in CLPs and proB cells after initiation of GM cell differentiation. EBF expression level in the sample shown in Fig. 3A (for A) and Fig. 3C (for B) was quantified by real-time PCR analysis.

Down-Regulation of Pax5 Is a Prerequisite Event in Lineage Conversion. Results shown in Fig. 3 prompted us to pursue the possibility that complete loss of Pax5 might be a prerequisite event during lineage conversion from lymphoid to myeloid lineage in CLPs and proB cells. If this is the case, we should not observe myeloid cell readout from IL-2RβTG CLPs upon IL-2 stimulation when Pax5 expression remains. To assess this issue, we introduced Pax5 into IL-2RβTG CLPs followed by IL-2 stimulation to induce lineage conversion. We introduced Pax5 into IL-2RβTG CLPs using the retrovirus system, as mentioned in Materials and Methods. Before ectopic Pax5+ IL-2RβTG CLPs were stimulated with IL-2, we examined Pax5 expression levels by real-time PCR. As shown in Fig. 5A, ectopic Pax5+ IL-2RβTG CLPs expressed slightly but not significantly higher Pax5 than freshly isolated CLPs and control GFP+ CLPs. Consistent with our previous results, control GFP+ IL-2RβTG CLPs gave rise to Mac-1+ myeloid cells in stromal cell cultures, although a large number of B220+ B cells developed (Fig. 5B). This could be attributed to our previous observation that CLPs can maintain their latent myeloid differentiation potential for only 2 days in vitro (9). During the period of in vitro culture for retroviral infection, a number of CLPs may already have committed to B lineage before addition of IL-2 to initiate lineage conversion. Nonetheless, in clear contrast to the control group, enforced Pax5 expression completely blocked myeloid cell differentiation from IL-2RβTG CLPs after stimulation with IL-2 (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Ectopic Pax5 blocks myeloid differentiation from IL-2RβTG CLPs after IL-2 stimulation. (A) After IL-2RβTG CLPs were infected with Pax5 and empty retrovirus, cells were cultured for 12 h at 37°C. GFP+ cells were FACS-sorted and subjected to real-time PCR analysis. Pax5 expression level in freshly isolated CLPs is also shown. (B) Retrovirally infected cells as A were cultured for another 12 h in the presence of IL-2 to initiate lineage conversion. After this preculture, GFP+ cells were sorted and cultured on OP9 stromal layers for 5 days. B and myeloid cell readout was determined by FACS.

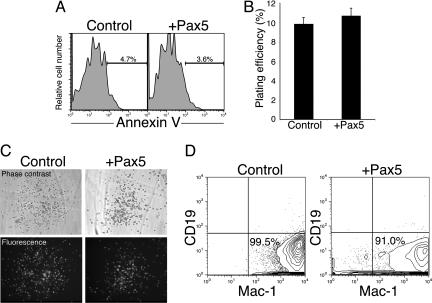

To rule out the possibility that ectopic Pax5 expression may induce apoptosis in myeloid cells, we further examined the effect of enforced Pax5 expression in CMPs. At 48 h after infection with control or Pax5 retrovirus in CMPs, we examined preapoptotic cells by annexin V staining and found there was no significant difference between these two groups (Fig. 6A). Therefore, ectopic Pax5 expression does not affect the survival of myeloid lineage-committed progenitors. Furthermore, Pax5+ CMPs formed GM colonies at the same efficiency as control GFP+ CMPs in methylcellulose cultures in the presence of IL-3 and GM-CSF (Fig. 6 B and C). In addition, CMPs gave rise to Mac-1+ cells in OP9 stromal cell cultures irrespective of the presence of ectopic Pax5 (Fig. 6D). These data strongly indicate that ectopic Pax5 expression does block lineage conversion in CLPs from lymphoid to myeloid lineage, but it does not interfere with myeloid lineage cell development. We should note that, although CD19 is a target gene of Pax5 (25), we did not observe any CD19+ cells develop from CMPs with ectopic Pax5 expression in this case (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Ectopic Pax5 expression does not affect the survival and differentiation of myeloid lineage committed progenitors. (A) CMPs were infected with retrovirus to ectopically express Pax5. Forty-eight hours after infection, annexin V staining was performed to determine the percentage of preapoptotic GFP+ cells. (B) Ectopic Pax5 expression does not affect myeloid differentiation potential of CMPs. CMPs were introduced with Pax5 by retroviral vectors. GFP+ cells were sorted onto methylcellulose medium supplemented with SCF, IL-3, IL-6, and GM-CSF. After 5–7 days of culture, the formation of colonies was observed under the microscope. The presence of ectopic gene was further confirmed by detecting GFP with fluorescence microscopy. There was no significant difference in plating efficiency between CMPs with or without ectopic Pax5 (C). (D) Pax5+ CMPs and control GFP+ CMPs after retroviral gene introduction were cultured on OP9 stromal cell layers in the presence of IL-3 and GM-CSF. After 6 days of the culture, readout cell types were determined by FACS.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that up-regulation of the myeloid-affiliated gene C/EBPα is a critical downstream event in IL-2R signaling to induce a latent myeloid differentiation potential in lymphoid progenitors. Expression of C/EBPα interrupted lymphoid development and induced myeloid differentiation from lymphoid progenitors. In addition, complete silencing of Pax5, a lymphoid-affiliated gene, was necessary for the progression of this lineage conversion process. Our data demonstrate that this down-regulation of Pax5 is not the result of lineage conversion from lymphoid to myeloid lineage, but it is a prerequisite event before lymphoid progenitors change cell fate.

Although we found a correlation between C/EBPα expression level and Pax5 down-regulation in proB cells, we cannot exclude the possibility that Pax5 silencing in IL-2-stimulated CLPs occurs as a consequence of IL-2R signaling independent of C/EBPα expression level (26). Upon IL-2 stimulation or introduction of C/EBPα in CLPs and proB cells, another B cell-specific transcription factor specification factor, EBF, was also down-regulated in addition to Pax5. Because EBF regulates Pax5 expression positively, Pax5 down-regulation might be the result of loss of EBF expression (24). However, when Pax5 expression was completely silenced by introduction of C/EBPα, EBF expression still remained. Because the introduction of Pax5 in thymocytes induces EBF expression (27), down-regulation of EBF might be induced by the loss of Pax5 in IL-2RβTG CLPs and proB cells after IL-2 stimulation. Furthermore, our preliminary result suggests that ectopic EBF expression is not sufficient to block IL-2-mediated lineage conversion in IL-2RβTG CLPs (C.-L.H. and M.K., unpublished observations). In any case, down-regulation of EBF and Pax5 might be a result of drastic change of gene expression due to change of chromosomal structure in the presence of C/EBPα.

In addition, it is not clear why the same IL-2 stimulation completely blocks Pax5 expression in CLPs but not in proB cells. The Pax5 expression level in proB cells was higher than in CLPs (Fig. 3 B and D). Therefore, a lower expression level of C/EBPα induced by IL-2 stimulation might not be sufficient to block Pax5 expression completely in proB cells (Fig. 3E). It is also possible that Pax5 expression is more stabilized in B lineage-committed progenitors (proB cells) than CLPs, which have multi-lymphoid lineage differentiation activity (3).

Transcription factors that are involved in commitment of one lineage may activate synergistic factors and antagonize the action or expression of transcription factors for another lineage. For example, PU.1, a transcription factor necessary for B and macrophage differentiation, was recently shown to directly regulate the EBF gene (28) but antagonized GATA-1, a fundamental factor for erythroid cell development (29–32) or Notch1, a crucial factor for T cell development (33). In this study, we show that the direct or indirect interaction of two transcription factors, C/EBPα and Pax5, determines the lineage choice in CLPs. Blockage of Pax5 function by ectopic C/EBPα has been proposed as a mechanism that changes the cell fate of B cell progenitors to macrophages (21). However, in this scenario, down-regulation of Pax5 expression may be simply the result of lineage conversion from B to macrophage because macrophages do not express Pax5 (21). We clearly show here that loss of Pax5 expression by ectopic C/EBPα or IL-2R signaling is indispensable for lineage conversion in CLPs and proB cells. In contrast, proT cells do not express Pax5 (34), and ectopic Pax5 expression in IL-2RβTG proT cells did not block myeloid cell readout initiated by IL-2 stimulation (A.G.K.-F., I.L.W., and M.K., unpublished observations). Therefore, it is possible that a T cell counterpart of Pax5, which determines T lineage commitment, may block this IL-2-mediated lineage conversion in proT cells.

Based on our results, we provide a possible explanation for why Heavey et al. (23) and Xie et al. (21) obtained controversial results in regard to the ability of proB cells in lineage conversion by using similar experimental approach. Xie et al. (21) might obtain high levels of C/EBPα expression that was enough to silence Pax5 expression in proB cells, as is the case in our study. In contrast, Heavey et al. (23) might not obtain high enough ectopic C/EBPα expression levels in proB cells, and the remaining Pax5 expression inhibited lineage conversion (23). Because Pax5–/– proB cells have multipotent differentiation potential, including erythroid lineage, lineage-specific transcription factors, such as GATA-1 and C/EBPα may induce specific lineage commitment even at low expression levels. In this context, apoptosis induction by ectopic GATA-1 in WT proB but not in Pax5–/– proB cells might be intriguing (13, 23). It is possible that this apoptotic induction might be a cell intrinsic fail-safe mechanism to eliminate abnormally developing cells.

In contrast to the effect of GATA-1 in proB cells, ectopic Pax5 expression did not affect the survival or differentiation of myeloid progenitors. It has also been reported that Pax5 does not affect lymphoid versus myeloid lineage decision from multipotent hematopoietic progenitors in vivo (33, 35). However, ectopic Pax5 blocked IL-2R-mediated lineage conversion in CLPs (Fig. 4). This suggests that the molecular regulation of lineage conversion events in lymphoid lineage-committed progenitors may not be equivalent to normal myeloid lineage commitment from multipotent progenitors.

Although our experimental system is artificial, we clearly demonstrated that antagonistic actions of lymphoid- and myeloid-related transcription factors induced by cytokine receptor signaling could determine lymphoid or myeloid lineage decision in developing hematopoietic cells. Detailed gene expression profiling of progenitors intermediate between HSCs and lineage-committed progenitors may provide more insight into the regulation of lymphoid and myeloid lineage commitment during normal hemato/lymphopoiesis. Furthermore, the specific signal transduction pathways that are activated via IL-2R or GM-CSF receptor to initiate myeloid cell developmental program in CLPs should be a next issue to be clarified.

Materials and Methods

Mice. C57BL/Ka-Thy-1.1 were used as WT Mice. Human IL-2Rβ transgenic (IL-2RβTG) mice (36) on C57BL/6 background were obtained from Tasuku Honjo (Kyoto University, Kyoto). This transgenic line was further backcrossed onto C57BL/Ka-Thy-1.1 background in our laboratory. All mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Duke University Medical Center Animal Care Facility. All experimental procedures related to laboratory mice were done according to guidelines specified by the institution.

Cell Sorting and FACS Analysis. All cell populations used in this study were double-sorted by FACS, as described (3, 9, 10). For CLP sorting, bone marrow cells were first stained with biotinylated-anti-CD27, followed by incubating with streptavidin-MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). After washing with staining buffer (Hanks' balanced salt solution with 2% FCS and 0.02% NaN3), CD27+ cells were enriched with autoMACS by POSSEL_S mode. After blocking CD27+-enriched bone marrow with rat IgG (Sigma), cells were stained with FITC-anti-Thy-1.1 (HIS51), PE-anti-IL-7Rα (A7R34), PE/Cy5-anti-Lineage (Lin) [B220 (RA3–6B2), CD3 (145–2C11), CD4 (RM4–5), CD8 (53–6.7), Gr-1 (RB6–8C5), Mac-1 (M1/70), and Ter119 (Ter119)], APC-anti-c-Kit (2B8), and Alexa Fluor 594-anti-Sca-1. CLPs are defined as CD27+Lin–IL-7Rα+Thy-1.1–c-KitloSca-1lo population. For HSC sorting, bone marrow cells were incubated with c-Kit MACS beads. Then c-Kit+ cells were enriched with autoMACS by POSSEL_S mode. Enriched cells were stained with FITC-anti-Thy-1.1, PE-anti-Sca-1 (E13–161.7), PE/Cy5-Lin, and APC-anti-c-Kit. HSCs are defined as Lin–/lo Thy-1.1loc-KithighSca-1high.

For myeloid progenitors, we stained c-Kit+ cell-enriched bone marrow with.FITC-anti-CD34 (RAM34), PE-anti-FcγR (2.4G2), PE/Cy5-anti-Lin containing anti-IL-7Rα (A7R34) and anti-Thy-1.1, Alexa Fluor 594-anti-Sca-1, and APC-anti c-Kit. CMPs are defined as Lin–Sca-1–c-KithighCD34loFcγRloThy-1.1–.

ProB/large preB, which is denoted by proB in this paper below, and preB populations were enriched by depleting non-B cells from bone marrow. Cells were first stained with PE/Cy5-CD3, CD4, CD8, Gr-1, and TER-119. After incubation of cells with anti-rat-IgG MACS beads, Lin+ cells were depleted on the autoMACS machine. Cells remained after depletion were stained for PE-anti-CD43 (S7), APC-anti-B220, and Texas red-anti-IgM. ProB and preB populations were defined as IgM–B220+CD43+ and IgM–B220+CD43–, respectively.

For purification of DN1 and DN2 cells, c-Kit+ thymocytes were enriched as described for HSC sorting. c-Kit+ cells were stained with FITC-anti-CD44 (IM7), PE-anti-CD25 (PC61), PE/Cy5-anti-CD4 and CD8, and APC-anti-c-Kit. DN1 and DN2 populations are defined as CD4–CD8–c-Kit+CD44+CD25– and CD4–CD8–c-Kit+CD44+CD25+. Dead cells were excluded as propidium iodide+ cells during sorting.

For in vitro myeloid cell differentiation analysis, cells were harvested and stained with PE-anti-B220 and APC-anti-CD11b to analyze lineage conversion in various progenitor populations. Apoptotic cells were detected with Annexin V using the PE Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences) following the manufacturer's protocol. Texas red-anti-IgM was obtained from Southern Biotechnology Associates. Alexa Fluor 594-anti-Sca-1 was prepared in our laboratories with standard procedures. PE-anti-CD43 was purchased from BD Biosciences. All other antibodies used in this study were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA).

Retroviral Gene Transfer and in Vitro Culture. C/EBPα and Pax5 cDNAs were inserted between the 5′ LTR and internal ribosome entry site (IRES) of murine stem cell virus-IRES-GFP vector. Retroviral production and infection were done as described (9). After infection, GFP+ cells were purified by FACS sorting and cultured on OP9 stromal cell layers in the presence of IL-3 and GM-CSF (10 ng/ml, R & D Systems) or on methylcellulose (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver) supplemented with cytokines as indicated in the figure legends.

RT-PCR and Quantitative PCR. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). First-strand synthesis and PCR were performed as described (9). Transcripts were amplified with Advantage Taq (Clontech) on Gene Amp PCR system 9700 (Applied Biosystems) for 30–35 cycles. Amplified products were subjected to electrophoresis, visualized under UV light, and analyzed by eaglesight software (Stratagene). Quantitative PCR was performed in triplicates on LightCycler (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis). The expression level of gene of interest was calculated and normalized to GAPDH by using relative expression software tool, kindly provided by M. Pfaffl (Technical University of Munich, Munich). Primer sequence and PCR conditions were as follows. C/EBPα: forward, 5′-CAAAGCCAAGAAGTCGGTGGACAA-3′; reverse, 5′-TCATTGTGACTGGTCAACTCCAGC-3′; annealing temperature, 55°C; cycles, 35; size, 150 bp. Pax5: forward, 5′-AGAGAAAAATTACCCGACTCCTC-3′; reverse, 5′-CATCCCTCTTGCGTTTGTTGGTG-3′; annealing temperature, 60°C; cycles, 35; size, 593 bp. EBF: forward, 5′-CATGTCCTGGCAGTCTCTGA-3′; reverse, 5′-CAACTCACTCCAGACCAGCA-3′; annealing temperature, 68°C; cycles, 35; size: 243 bp. GAPDH: forward, 5′-CCTGGAGAAACCTGCCAAGTATG-3′; reverse, 5′-AGAGTGGGAGTTGCTGTTGAAGTC-3′; annealing temperature, 64°C; cycles, 30; size, 150 bp.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lynn Martinek and Mike Cook for FACS sorting. We also thank Mike Krangel for allowing us to access to a real-time PCR machine. This work was supported in part by Duke Stem Cell Research Program Annual Award (to M.K.), National Institutes of Health Grants R01 CA42551, R01 AI47457, and R01 AI47458 (to I.L.W.); T32 AI52077 (to A.Y.L.); and R01 AI056123 and R01 CA098129 (to M.K.). M.K. was a scholar of the Sidney Kimmel Foundation for Cancer Research.

Conflict of interest statement: I.L.W. was a member of the scientific advisory board of Amgen and owns significant Amgen stock. He cofounded and consulted for Systemix, is a cofounder and director of Stem Cells, Inc., and recently cofounded Cellerant, Inc. None of these companies is involved in studies regarding the lineage conversion described in this paper.

Abbreviations: CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; IL-2R, IL-2 receptor; C/EBPα, CCAAT enhancer-binding protein-α; GM, granulocyte/macrophage; GM-CSF, GM–colony-stimulating factor; TG, transgenic; EBF, early B cell factor; IL-2RβTG, IL-2Rβ transgenic.

References

- 1.Kondo, M., Wagers, A. J., Manz, M. G., Prohaska, S. S., Scherer, D. C., Beilhack, G. F., Shizuru, J. A. & Weissman, I. L. (2003) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 759–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orkin, S. H. (2000) Nat. Rev. Genet. 1, 57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kondo, M., Weissman, I. L. & Akashi, K. (1997) Cell 91, 661–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akashi, K., Traver, D., Miyamoto, T. & Weissman, I. L. (2000) Nature 404, 193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adolfsson, J., Mansson, R., Buza-Vidas, N., Hultquist, A., Liuba, K., Jensen, C. T., Bryder, D., Yang, L., Borge, O. J., Thoren, L. A., et al. (2005) Cell 121, 295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai, A. Y., Lin, S. M. & Kondo, M. (2005) J. Immunol. 175, 5016–5023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahl, R., Walsh, J. C., Lancki, D., Laslo, P., Iyer, S. R., Singh, H. & Simon, M. C. (2003) Nat. Immunol. 4, 1029–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kikuchi, K., Lai, A. Y., Hsu, C. L. & Kondo, M. (2005) J. Exp. Med. 201, 1197–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kondo, M., Scherer, D. C., Miyamoto, T., King, A. G., Akashi, K., Sugamura, K. & Weissman, I. L. (2000) Nature 407, 383–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King, A. G., Kondo, M., Scherer, D. C. & Weissman, I. L. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 4508–4513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwasaki-Arai, J., Iwasaki, H., Miyamoto, T., Watanabe, S. & Akashi, K. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 197, 1311–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu, J. & Emerson, S. G. (2002) Oncogene 21, 3295–3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwasaki, H., Mizuno, S., Wells, R. A., Cantor, A. B., Watanabe, S. & Akashi, K. (2003) Immunity 19, 451–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terskikh, A. V., Miyamoto, T., Chang, C., Diatchenko, L. & Weissman, I. L. (2003) Blood 102, 94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman, A. D. (2002) Int. J. Hematol. 75, 466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosmarin, A. G., Yang, Z. & Resendes, K. K. (2005) Exp. Hematol. 33, 131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang, D. E., Zhang, P., Wang, N. D., Hetherington, C. J., Darlington, G. J. & Tenen, D. G. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 569–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hohaus, S., Petrovick, M. S., Voso, M. T., Sun, Z., Zhang, D. E. & Tenen, D. G. (1995) Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 5830–5845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radomska, H. S., Huettner, C. S., Zhang, P., Cheng, T., Scadden, D. T. & Tenen, D. G. (1998) Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 4301–4314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang, P., Nelson, E., Radomska, H. S., Iwasaki-Arai, J., Akashi, K., Friedman, A. D. & Tenen, D. G. (2002) Blood 99, 4406–4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie, H., Ye, M., Feng, R. & Graf, T. (2004) Cell 117, 663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mikkola, I., Heavey, B., Horcher, M. & Busslinger, M. (2002) Science 297, 110–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heavey, B., Charalambous, C., Cobaleda, C. & Busslinger, M. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 3887–3897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Riordan, M. & Grosschedl, R. (1999) Immunity 11, 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nutt, S. L., Morrison, A. M., Dorfler, P., Rolink, A. & Busslinger, M. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 2319–2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rinkenberger, J. L., Wallin, J. J., Johnson, K. W. & Koshland, M. E. (1996) Immunity 5, 377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuxa, M., Skok, J., Souabni, A., Salvagiotto, G., Roldan, E. & Busslinger, M. (2004) Genes Dev. 18, 411–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medina, K. L., Pongubala, J. M., Reddy, K. L., Lancki, D. W., Dekoter, R., Kieslinger, M., Grosschedl, R. & Singh, H. (2004) Dev. Cell 7, 607–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rekhtman, N., Radparvar, F., Evans, T. & Skoultchi, A. I. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1398–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang, P., Zhang, X., Iwama, A., Yu, C., Smith, K. A., Mueller, B. U., Narravula, S., Torbett, B. E., Orkin, S. H. & Tenen, D. G. (2000) Blood 96, 2641–2648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang, P., Behre, G., Pan, J., Iwama, A., Wara-Aswapati, N., Radomska, H. S., Auron, P. E., Tenen, D. G. & Sun, Z. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 8705–8710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nerlov, C., Querfurth, E., Kulessa, H. & Graf, T. (2000) Blood 95, 2543–2551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Souabni, A., Cobaleda, C., Schebesta, M. & Busslinger, M. (2002) Immunity 17, 781–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyamoto, T., Iwasaki, H., Reizis, B., Ye, M., Graf, T., Weissman, I. L. & Akashi, K. (2002) Dev. Cell 3, 137–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cotta, C. V., Zhang, Z., Kim, H. G. & Klug, C. A. (2003) Blood 101, 4342–4346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asano, M., Ishida, Y., Sabe, H., Kondo, M., Sugamura, K. & Honjo, T. (1994) J. Immunol. 153, 5373–5381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]