Abstract

The E2A locus is a frequent target of chromosomal translocations in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL). E2A encodes two products, E12 and E47, that are part of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family of transcription factors and are central in B lineage differentiation. E2A haplo-insufficiency hinders progression through three major checkpoints in B-cell development: commitment into the B lineage, at the pro-B to pre-B transition, and in the induction of immunoglobulin M (IgM) expression required for a functional BCR. These observations underscore the importance of E2A gene dosage in B-cell development. Here we show that a higher proportion of pro-B cells in E2A+/− mice is in the cell cycle compared to that in wild-type littermates. This increase correlates with lower p21waf/cip1 levels, indicating that E2A has an antiproliferative function in B-cell progenitors. Ectopic expression in the B lineage of SCL/Tal1, a tissue-specific bHLH factor that inhibits E2A function, blocks commitment into the B lineage without affecting progression through later stages of differentiation. Furthermore, ectopic SCL expression exacerbates E2A haplo-insufficiency in B-cell differentiation, indicating that SCL genetically interacts with E2A. Taken together, these observations provide evidence for a gradient of E2A activity that increases from the pre-pro-B to the pre-B stage and suggest a model in which low levels of E2A (as in pro-B cells) are sufficient to control cell growth, while high levels (in pre-B cells) are required for cell differentiation. The antiproliferative function of E2A further suggests that in B-ALL associated with t(1;19) and t(17;19), the disruption of one E2A allele contributes to leukemogenesis, in addition to other anomalies induced by E2A fusion proteins.

The development of B lymphocytes from hematopoietic stem cells is a complex and highly regulated process that results in antigen-responsive B cells with individual immunoglobulin (Ig) receptors. Gene disruption experiments have shown that an ordered network of transcription factors is needed to achieve this differentiation process. The initial stages in B-cell development depend on E47 and E12 (products of the E2A gene) (3, 4, 24). Targeted disruption of this gene results in a complete block of B-cell differentiation before the initiation of IgH locus recombination, indicating that this transcription factor is involved in B-cell specification. E2A gene products belong to the ubiquitously expressed basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor family (also named E proteins) that binds DNA as homodimers or heterodimers on E box elements (CANNTG). A unique form of this transcription factor exists in B cells consisting of an E47 homodimer that results from B-cell-specific posttranslational modifications of the protein (6, 46). The formation and the function of this specific homodimer depend on the balance between E2A gene products, other bHLH factors (HEB and E2-2), and the E protein inhibitors named Id proteins—the non-DNA binding partners of all E proteins. Mice lacking HEB or E2-2 or Id transgenic mice are still able to produce B cells, but the number of pro-B cells is reduced (50, 57). E2A induces the expression of an essential B-cell transcription factor, Pax-5 (BSAP), that acts not only by turning on several B-cell-specific genes (CD19, mb-1, germ line IgH transcript), but also by turning off the other developmental programs of hematopoietic precursors (24, 33, 35, 42). Together, these observations indicate that the dosage relationship between E12 and E47, other bHLH factors, and Id proteins regulates the functional activity of E47 homodimers and determines outcome in B lineage commitment and differentiation. Although these observations indicate the critical role of E proteins in B-lymphocyte differentiation, it remains to be determined in which processes and at which differentiation steps E2A activity is required.

SCL/Tal1 is a bHLH transcription factor that is essential for blood cell development (41, 47). SCL expression is highest in multipotent and erythroid progenitors and decreases with differentiation in all lineages (7, 17, 31, 39 [reviewed in reference 5]). SCL gene products form heterodimers with E proteins (E47, E12, and HEB) and bind DNA within oligomeric complexes that act as activators or repressors of transcription, depending on the target gene and the cellular context (16, 22, 34; Lecuyer et al., unpublished data). Aberrant activation of SCL, either by chromosomal translocation or interstitial deletion, is the most frequent activation of a specific gene in childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) (reviewed in reference 5). SCL collaborates with LMO1 or LMO2 to induce T-ALL in transgenic mice, in which SCL expression is targeted to the thymus (1, 26). Interestingly, SCL is found in a complex with LMO2 in leukemic T cells and erythroid cells (52), and genes encoding LMO1 and LMO2 are the second most frequent targets of chromosomal translocations in T-ALL (reviewed in reference 40). We have recently shown that SCL collaborates with LMO1 to induce a partial T-cell differentiation arrest in the preleukemic phase, due to disrupted pTα expression, a novel and critical target of E2A or HEB in the thymus (16). Interestingly, E2A-deficient mice that escape perinatal lethality survive to adulthood and develop T-cell leukemia (2, 55). Similarly, the E2A HLH antagonist Id1 causes massive apoptosis in the thymus, and the mice eventually develop leukemia (25). These observations suggest that the inhibition of E2A function is important for T-cell transformation (reviewed in reference 32).

Here we show that SCL/Tal1 and E2A exhibit opposite expression patterns: i.e., SCL is turned off at an early stage of B-cell maturation, while E2A levels increase. We investigate the consequences of perturbing the dosage between SCL and E2A in the B lineage in SIL-SCL transgenic mice and in mice lacking one functional E2A allele. Our data underscore the critical importance of bHLH dosage in B-cell development at the commitment stage, at the pro-B to pre-B transition, and the switch to IgM+ cells, and reveal an important function of E2A in cell cycle control of developing B cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenic mice.

We have used the A(5)3SCL line that expresses the amino-terminal truncated form of human SCL under the control of the ubiquitous SIL promoter, as previously described (1). E2A+/− mice (58) were kindly provided by Y. Zhuang (Duke University Medical center, Durham, N.C.). Animals were maintained under pathogen-free conditions according to institutional animal care and use guidelines. Mice were genotyped by PCR. Southern analyses were performed to distinguish SIL-SCL heterozygotic (SCLtg) from SCL homozygotic (SCLtg/tg) mice.

FACS analysis and cell sorting.

Bone marrow, thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes were removed from mice ranging from 4 to 7 weeks of age. Single-cell suspension and immunostaining were performed as previously described (16). Bone marrow cells were stained with allophycocyanin (APC)-B220, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-CD43, phycoerythrin (PE)-BP1, and biotin-CD24 conjugates for fractions A to C or APC-B220, FITC-CD43, biotin-IgM conjugates for fractions D to F. Red670- or PharRed-streptavidin was used to reveal biotinylated conjugates. Four-color immunofluorescence analyses were performed on FACStar or FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson) by dual laser excitation. When fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) was performed, 10,000 to 25,000 cells were collected according to their surface markers for PCR and cell cycle analysis, while 106 to 3 × 106 cells were collected for preparation of nuclear extracts.

RNA preparations, cDNA synthesis, and PCR amplification.

Total RNA was prepared according to the protocol of Chomczynski and Sacchi (10), with tRNA as a carrier for ethanol precipitation. First-strand cDNA synthesis and specific PCR were performed as described previously (16). Twenty-eight cycles of amplification were performed, and 10 μl of each reaction mixture was loaded on a 1.2% agarose gel, transferred on nylon membrane (Nytran), and hybridized with the corresponding internal oligonucleotide probes (Table 1). The hybridization signals were analyzed on a PhosphorImager apparatus, and ImageQuant software was used for quantification.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Primer sequence

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3′ | 5′ | Internal | |

| mSCL | ATTGATGTACTTCATGGCAAGG | TCCCCATATGAGATGGAGATTT | TGGAGATTTCTGATGGTCCTCACACCAAA |

| mGATA1 | CATGCTCCACTTGACACTGA | GGAGACAGGATCTTCTGTAG | TTCAGGCATGTATTGCTATGCCT |

| mS16 | GCTACCAGGGCCTTTGAGAT | AGGAGCGATTTGCTGGTGTG | CCAAATTTATGATCCGACAGT |

| mE2A | AAGCATACAGGACTGCAAGGAG | GCATAGGAAGCTCAGCAGAGA | AATCAGTGTGTCGCTTCTGCAC |

| SCLtg | ATGTGTGGGGATCAGCTTGC | GCTCCTACCCTGCAAACAGA | TGGAGATTTCTGATGGTCCTCACACCAAA |

| mPax-5 | GATCCTTGATGGAGCTGACG | TCAGGACAGGACATGGAGGAG | GCAGGTATTATGAGACAGGAAGCAT |

| mRAG1 | CAGACTCACTTCCTCATTGCAA | CATGCACAGAAAGTTCAGCAGT | GTACCAAGCTTCTTGCCGTGGA |

| c-kit | CATTTATGAGCCTGTCGTACGT | TGTCTCTCCAGTTTCCCTGC | ACAACACTCTTATCGTAGAC |

| p21wal/cip1 | AACTTTGACTTCGTCACGGAGA | AATCTGCGCTTGGAGTGATAGA | CAGTACTTCCTCTGCCCTGCTG |

Genomic PCR analysis.

Rearrangements of the IgH locus were analyzed by genomic DNA PCR as previously described (45). For genomic DNA preparation, 106 cells were lysed in PCR lysis buffer (1× PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.45% NP-40, 0.45% Tween 20, 60 μg of proteinase K per ml) for 2 h at 55°C. Serial dilutions of the lysate were used for amplification, and 10 μl of PCR products was loaded onto the gel, which was then transferred and hybridized with the JH4 internal primer (45).

Limiting dilution analysis.

The frequency of bone marrow cells that give rise to pre-B cells in the Whitlock-Witte in vitro culture system was determined with a limiting dilution assay. S17 cells were seeded at 3 × 103 cells/well in 96-well dishes in RPMI 1640 medium–5% fetal calf serum (FCS). Four days later, bone marrow from wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous SCL transgenic littermates was serially diluted in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with a mixture containing 5% B-cell-tested FCS (stem cell), 50 μg of gentamicin per ml, and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol and seeded on S17 cells at different cell concentrations ranging from 60,000 to 500 cells per well. Each dilution was plated in 12 individual wells. Cultures were fed once a week by aspirating half of the medium and adding the same volume of fresh medium. After 21 days, cultures were screened for the presence of lymphocyte colonies, and the frequency of pro-B cells was calculated by applying Poisson statistic (LDA software). B cells from positive wells were harvested and analyzed by FACS with PE-B220, CD43-FITC, and biotin-IgM antibodies.

Hoechst 33342 staining of bone marrow cells.

Bone marrow was extracted from the femurs of 4- to 6-week-old mice, and the single-cell suspension was stained with Hoechst 33342 vital dye as described by Goodell et al. (14). After Hoechst staining, cells were pelleted and incubated with lineage-specific antibodies (B220 and CD11b) at 4°C before FACS analysis, which was performed with a dual laser MoFlo cytometer (Cytomation).

Cell cycle analysis.

Fractions A to EF were purified by flow cytometry as described above. Twenty thousand cells were collected in DNA staining solution (0.1% sodium citrate, 0.02 mg of RNase A per ml, 0.3% NP-40, 0.05 mg of propidium iodide per ml) and incubated on ice for 30 min. DNA contents were analyzed on a Coulter flow cytometer, and cell cycle profiles were determined with Mcycle software.

Gel shift analysis.

Pro-B, pre-B, and mature B cells were purified from wild-type and SCL transgenic bone marrows by cell sorting, as described above. Nuclear extracts were prepared from 1 to 3 million sorted cells. Briefly, cells were resuspended in 100 μl of hypotonic buffer (10 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.9], 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 10 μg of aprotinin per ml, 1 μg of leupeptin per ml, 10 μg of pepstatin A per ml, 10 μg of antipain per ml) and incubated for 8 min on ice. Nuclei were centrifuged at 1,800 × g for 1 min at 4°C, resuspended in 10 to 20 μl of extraction buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 400 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 5% glycerol, 2 mM PMSF, 10 μg of aprotinin per ml, 1 μg of leupeptin per ml, 10 μg of pepstatin A per ml, 10 μg of antipain per ml), and rotated at 4°C for 1 h 30 min. Debris and DNA were removed by ultracentrifugation at 40,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C.

DNA binding assays were performed as described previously (11) by using the TAL-1 consensus probe (20) or PU1 (TCAGCCTCCTACTTCTGCTTTTGAAAGCTA) radiolabeled oligonucleotide probes. Where indicated, nuclear extracts were incubated for 30 min on ice with a monoclonal anti-E2A (Yae; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), a monoclonal anti-human SCL (BTL-73; gift from D. Mathieu-Mahul [39]) or control IgG (Sigma, Saint Louis, Mo.). Protein-DNA complexes were resolved by electrophoresis in 4% acrylamide gels (140 V for 3 h at 4°C). Gels were dried and exposed to a phosphor screen.

Immunohistochemistry.

B-cell fractions were purified by flow cytometry as described above. Cells were fixed in Bouin’s fixative for 20 min at room temperature, washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and cytocentrifuged on gelatin-coated slides. After inactivation of the endogenous peroxidase by incubation in 1% H2O2 for 10 min, nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation with 10% normal goat serum in PBS for 1 h, followed by an incubation with a rabbit polyclonal anti-E2A antibody (V-18; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 2 h at room temperature. Slides were dipped in PBS to remove excess antibodies and washed twice in PBS for 5 min each. Slides were then incubated with a biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) and streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase for 1 h each at room temperature. Positive cells were revealed by incubation with the peroxidase substrate (diaminobenzidine [DAB]; Sigma, Saint Louis, Mo.) for 5 min and counterstained with methyl green.

Western blot analysis.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared from sorted pro-B (fraction ABC), pre-B (fraction D), and B (fraction EF) cells that were purified from adult C57BL6/J bone marrow. Fifteen micrograms of proteins was resolved by electrophoresis on SDS-10% polyacrylamide gels and blotted on polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore Corporation, Bedford, Mass.). We used a monoclonal anti-E2A antibody (Yae; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) that reacts with both E12 and E47 and a rabbit polyclonal anti-E2A antibody (N-649; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) that detects only E47 proteins. Blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-PTP 1D (BD Biosciences) as a loading control. Quantifications were performed with ImageQuant software.

RESULTS

SCL is downregulated at an early stage of B-cell differentiation.

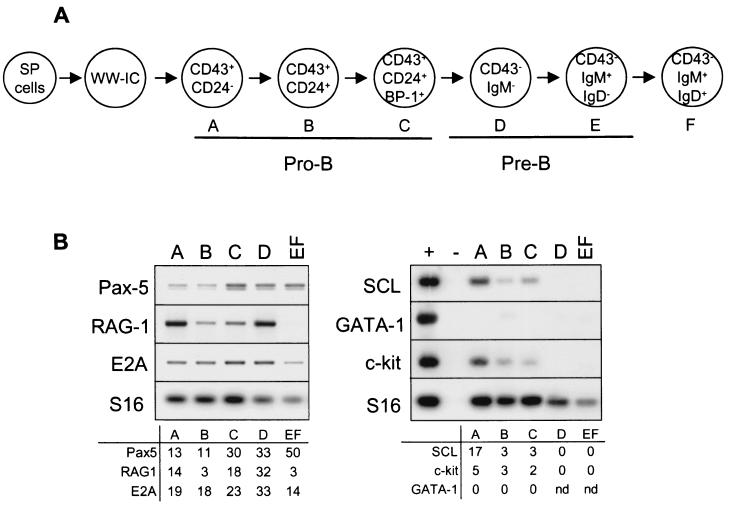

The SCL transcription factor is expressed in immature hematopoietic precursors as well as in the erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages (7, 17, 31, 39). In the T lineage, we have recently shown that SCL and E2A exhibit opposite expression patterns: i.e., that SCL transcripts are present in immature thymocytes (DN1 and DN2) and decrease in the DN3 population, concomitant with an increase in E2A and HEB levels (16). Furthermore, we showed that SCL collaborates with LMO1 to inhibit E2A and HEB function in the thymus. Because of the importance of bHLH dosage in B-cell development, we assessed the pattern of SCL expression during B-cell development. Populations presumed to be developmentally sequential pro-B subsets were resolved on the basis of successive expression of CD24 and BP-1 within the CD43+ B220+ compartment and IgM expression within CD43− B220+ population (Fig. 1A, fractions A to EF according to Hardy’s classification [15]). B-cell stages in these fractions were assessed by the presence of known molecular markers. As shown in Fig. 1B, c-kit expression is high in fraction A and decreases with differentiation, while Pax-5 mRNA levels increase in fractions C to F. Furthermore, the RAG-1 mRNA level is maximal in fractions A and D, when cells rearrange the Ig heavy-chain and light-chain genes, respectively. We observed that SCL transcripts are highest in fraction A and rapidly decrease as differentiation proceeds from fractions A to C. Recent reports have shown that fraction A is heterogeneous and contains a large proportion of non-B-cell committed precursors (51). Since SCL is coexpressed with GATA-1 in hematopoietic progenitors (7, 17), we monitored the presence of GATA-1 transcripts in purified fractions A to EF. As shown in Fig. 1B, GATA-1 mRNAs are absent in all fractions, suggesting that the presence of SCL in fraction A is not due to contaminating progenitors. The weak expression of SCL in fractions B and C may result from overlapping mixtures of B cells at various differentiation stages (30).

FIG. 1.

SCL gene expression is downregulated in differentiating B cells. (A) Schematic diagram of B-cell differentiation by using Hardy’s classification. (B) SCL expression in purified B-cell precursors. Bone marrow B-cell precursors were purified by flow cytometry according to Hardy’s protocol (15), and gene expression was investigated by RT-PCR. Molecular markers (Pax-5, RAG-1, E2A, and c-kit) were investigated to confirm the developmental stages of purified B cells, and GATA-1 amplification was used to check for non-B-cell contamination. The positive control (+) was obtained with unfractionated bone marrow cells. Hybridization signals were measured by using the ImageQuant software and normalized for the amount of cDNA with S16 as a control. nd, not determined.

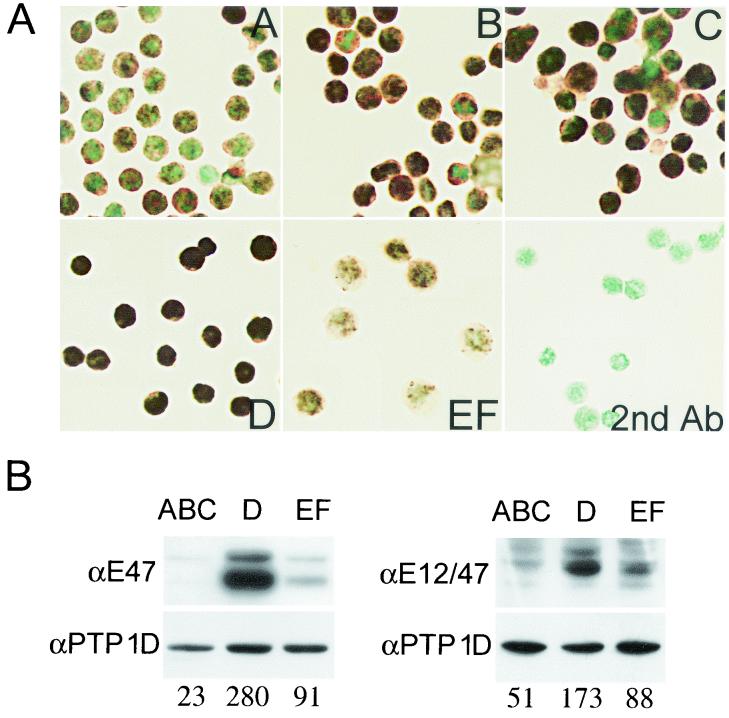

In contrast to SCL, E2A mRNA levels increase from fraction C to fraction D and then decrease in fraction EF (Fig. 1B). Although this increase in E2A mRNA levels is weak, we observed by immunohistochemical labeling and Western blot analysis that E2A proteins reach a maximum in fraction D and level off in mature B cells (Fig. 2). The increase in E2A proteins revealed by Western blotting is overestimated by virtue of the larger size of pro-B cells compared to pre-B cells and, consequently, the higher yield of protein extraction from pro-B cells. Nonetheless, it is interesting to observe that the increase of E47 protein levels from pro-B to pre-B cells was 12-fold (Fig. 2B, left panel), whereas the increase was only 3.5-fold when E12 and E47 were monitored together (Fig. 2B, right panel). This observation indicates that there is a specific increase in E47 versus E12 protein at the pro-B to pre-B transition.

FIG. 2.

E2A protein levels increase from pro-B to pre-B stages and decrease in mature B cells. (A) B-cell fractions (A to EF) were sorted by flow cytometry, fixed in Bouin’s solution, and cytocentrifuged on gelatin-coated slides. E2A proteins were detected by immunoperoxidase staining as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Western blots were performed on total cell lysates prepared from sorted bone marrow pro-B (ABC), pre-B (D), and B cells (EF). E47 proteins (left panel) or E47 and E12 proteins (right panel) were revealed by Yae monoclonal or N-649 polyclonal anti-E2A antibodies (Ab), respectively. Signals were measured by using the ImageQuant software and normalized for the amount of protein with PTP 1D as a control.

In summary, our observations indicate that SCL and E2A exhibit opposite expression profiles: i.e., SCL expression is repressed at an early stage of B-cell differentiation, just before or early after B-cell commitment, while E2A levels increase steadily. Hence, the SCL expression profile resembles that previously described for Id proteins (27), suggesting that SCL downregulation is necessary to allow E2A proteins to become functional. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the consequences of ectopic SCL expression on B-cell differentiation.

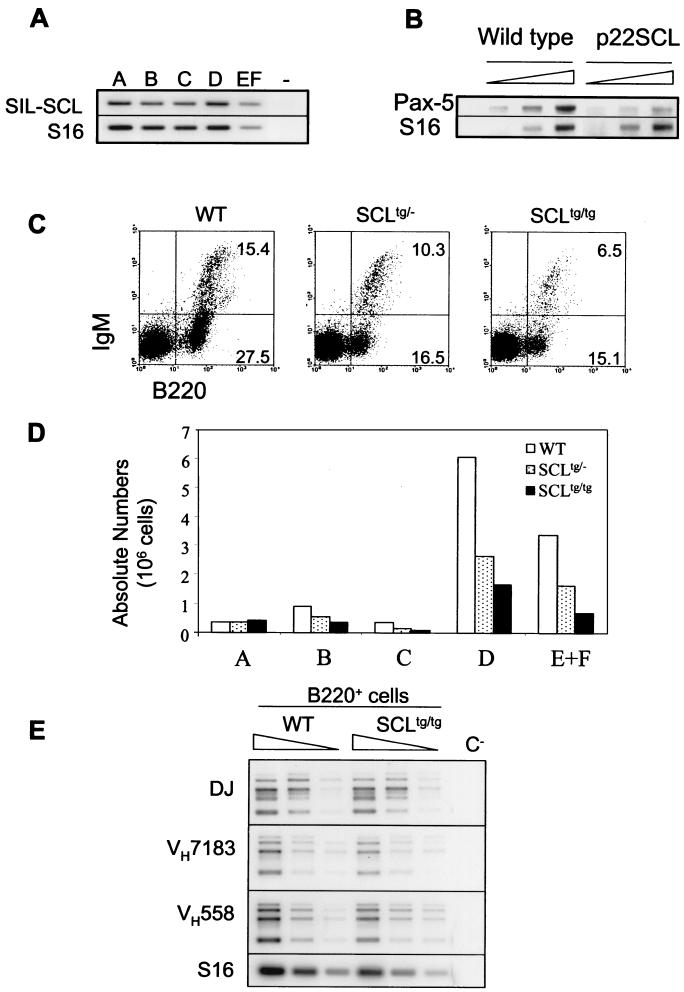

SCL overexpression blocks B-cell differentiation at the early pro-B stage.

We analyzed the B-cell compartment of bone marrow from heterozygous and homozygous SIL-SCL transgenic mice (1), in which the ubiquitous SIL promoter drives the expression of the human amino-terminal-truncated form of SCL (p22SCL) in all cells. As shown in Fig. 3A, the SCL transgene is equally expressed in fractions A to EF. Pax-5 transcripts, encoding a B-cell-specific transcription factor, were significantly decreased in bone marrow cells from SCL transgenic mice compared to wild-type littermates (Fig. 3B), suggesting an overall decrease in B-cell number. Flow cytometry analysis of total bone marrow cells indicates that the myeloid lineages are not affected by SCL overexpression (data not shown), whereas the B lineage is markedly reduced in SCL transgenic mice, as shown by the decrease in both percentages (Fig. 3C) and absolute numbers of B220+ cells (Fig. 3D). We therefore analyzed B-cell precursor populations by using surface markers as described above and observed that SCL transgenic mice display normal numbers of cells in fraction A, while fractions B and C are reduced in percentage as well as in absolute numbers (Fig. 3C and D). Interestingly, homozygous SCL transgenic mice display a more severe B-cell deficiency than heterozygous littermates, indicating that the decrease in B cells was proportional to transgene copy numbers. More mature bone marrow B cells (B220+ CD43− IgM− and IgM+ [fractions D and EF, respectively]) were also reduced in SCL transgenic mice in a dose-dependent manner. The relative ratios of the B to EF populations were normal in SCLtg/tg mice, suggesting that the cells that escape the initial block can mature normally, except for a slight decrease in the transition to IgM+ cells. We next performed cell cycle analysis within purified B-cell precursors (fractions A to EF) and did not observe any decrease in numbers of cells in the G2/M and S phases (data not shown), indicating that the decrease in pro-B-cell numbers is not due to defective cell proliferation. Furthermore, the expression of B-cell-specific genes, as assessed by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) on purified B-cell subsets (data not shown), and rearrangements of the IgH locus, as assessed by PCR on genomic DNA of B220+ cells (Fig. 3E), were not significantly different between SCLtg mice and control littermates. Finally, the numbers of B cells in secondary lymphoid organs are not significantly affected (data not shown). Together these data indicate that SCL overexpression affects the initial stage of B-cell differentiation, but has no obvious effect beyond the early pro-B stage and that cells that escape the initial block mature normally.

FIG. 3.

Impaired B-cell development in SCL transgenic mice. (A) SCL transgene expression in purified B-cell populations. RT-PCR analysis was done with SIL and SCL primers to quantify the expression level of the SCL transgene within the different subsets of B-cell precursors. (B) Decreased amount of Pax-5 transcripts in SCLtg bone marrow cells. Semiquantitative RT-PCRs were performed on unfractionated bone marrow cells from wild-type and SCLtg/tg littermates. S16 served as a control for the amount of cDNA. (C) Dose-dependent decrease of B-cell numbers in SCLtg mice. Bone marrow B-cell populations of wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous SCLtg littermates were analyzed by FACS. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Absolute cell numbers were calculated from the relative percentages obtained in panel B and the total numbers of bone marrow cells. (E) SCL overexpression does not affect V(D)J rearrangements at the IgH locus. Genomic DNA was prepared from purified B220+ cells from wild-type and SCLtg/tg littermates, and serial dilutions were used for PCR amplification of DJ and V(D)J rearranged segments. A Southern blot of amplification products was hybridized with Jh4 internal probe. S16 gene amplification was used as a control for amounts of DNA.

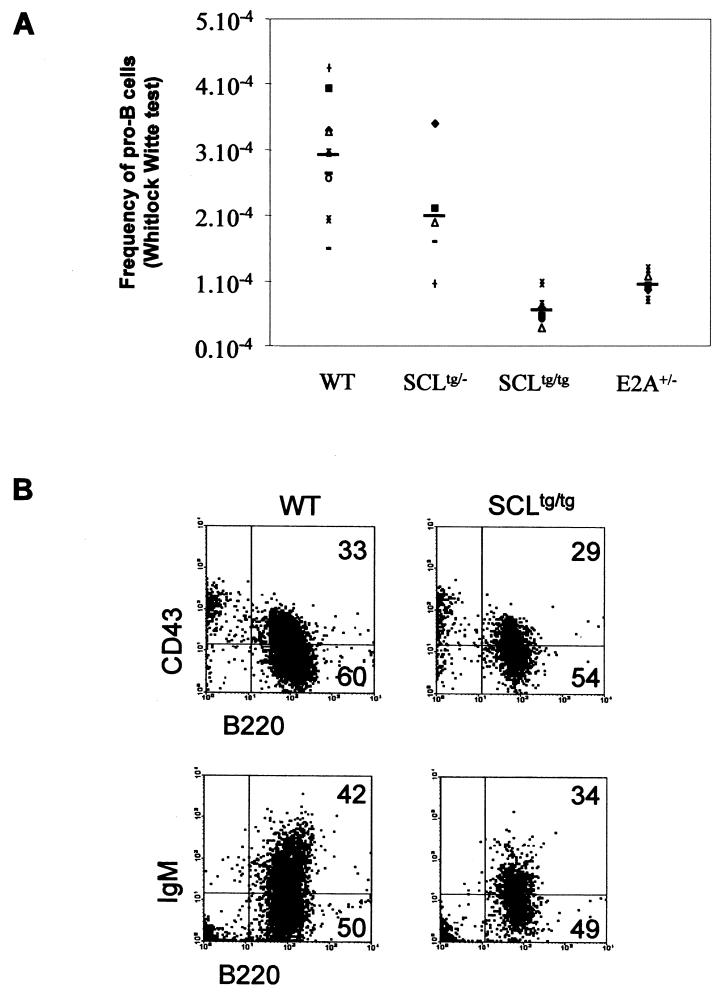

The heterogeneity of Hardy’s fraction A that can include non-B cells (51) led us to assess the pro-B-cell compartment in a functional assay and to evaluate the frequency of Whitlock-Witte culture-initiating cells (WW-IC) in heterozygous and homozygous SCL transgenic and control bone marrows. Limiting dilutions of bone marrow cells were seeded on the S17 stromal cell line that supports B-cell differentiation and proliferation (12, 54). After 21 days, positive cultures were scored, and Poisson’s statistic tests were performed to evaluate the frequency of pro-B cells in initial bone marrow populations. As shown in Fig. 4A, SCL heterozygous and homozygous mice exhibit 30 and 90% reductions of pro-B cells, respectively. Hence, despite an apparent normal number of cells in fraction A, ectopic SCL expression blocks B-cell differentiation at the early pro-B stage. SCLtg B cells generated in Whitlock-Witte cultures differentiate normally, and the proportions of B220+ and B220+ CD43+ cells were not significantly different from those of controls (Fig. 4B). We, however, observed a decrease in IgM+ cells, in particular in the IgMhigh population (Fig. 4B). These data agree with our in vivo observations (Fig. 3) and confirm that ectopic SCL expression induces a decrease of the early pro-B-cell population and lightly affects the D-to-EF transition.

FIG. 4.

Decreased frequency of pro-B cells (WW-IC) in SCL transgenic bone marrow and in E2A+/− bone marrow. (A) Whitlock-Witte assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The average frequency of pro-B cells for each phenotype is also shown (thick lines) (wild type [WT], n = 9; SCLtg/−, n = 5; SCLtg/tg, n = 8; E2A+/−, n = 5). (B) Normal differentiation of WW-IC from SCL transgenic bone marrow. After 21 days of culture, B cells were collected from positive wells and analyzed for the expression of B220, CD43, and IgM by flow cytometry. Dead cells were removed by gating on the Annexin Vneg 7AADneg population.

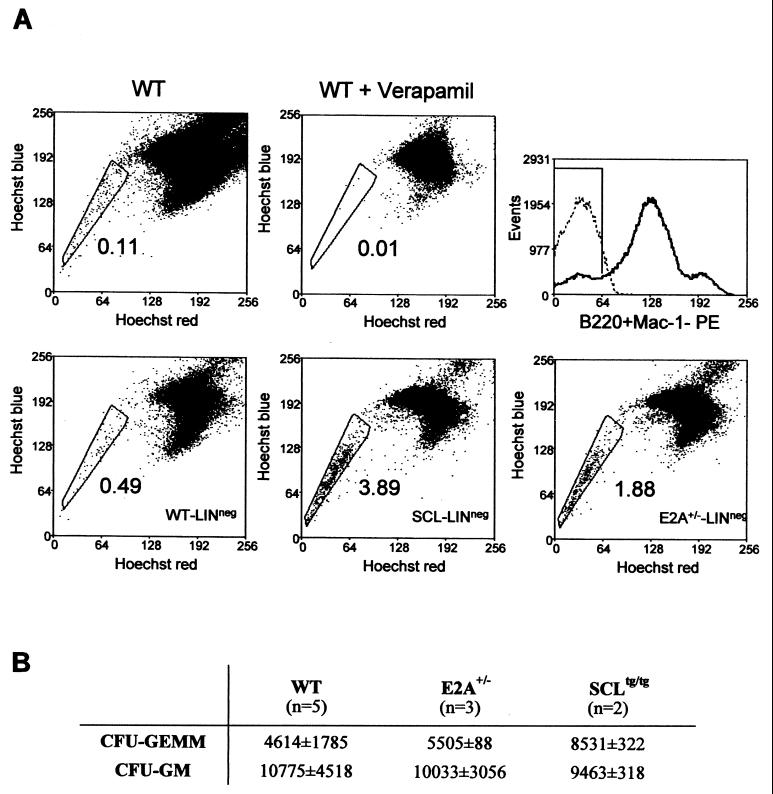

In order to address the possibility of whether the observed decrease in WW-IC is due to a decrease in a primitive multipotent stem cell population or a specific decrease in the B lineage, we performed Hoechst 33342 staining and methylcellulose cultures of bone marrow cells from SCL transgenic and wild-type littermates. Dual-wavelength analysis of Hoechst 33342 fluorescence reveals a side population (SP cells) highly enriched in hematopoietic stem cells (14). As shown in Fig. 5A, SP cells represent on average 0.1% of total bone marrow cells or 0.5% of Lin− cells from wild-type mice, and this population is specifically inhibited by the drug verapamil, as expected (14). Interestingly, SCL transgenic bone marrow exhibits an eightfold increase in B220− CD11b− SP cells compared to the level in controls (Fig. 5A), suggesting an increased number of stem cells or early immature precursors. This observation correlates with an increased number of multipotent progenitors (CFU-GEMM) when SCL transgenic bone marrow was plated in semisolid medium for in vitro myeloid differentiation (Fig. 5B). Together, these observations suggest that ectopic SCL expression specifically blocks the transition between Lin− SP cells and WW-IC, i.e., near or at the B-cell commitment step.

FIG. 5.

Ectopic SCL expression or a partial E2A loss of function increases SP cells. (A) SP cells are increased in SCLtg and E2A+/− mice. Dual-wavelength analysis of Hoechst 33342 was performed on bone marrow cells from SCLtg, E2A+/−, and wild-type (WT) mice. Hoechst efflux was specifically inhibited by verapamil. Lineage-negative cells were analyzed for SCLtg, E2A+/−, and wild-type bone marrows. The boxed regions correspond to the SP regions, and the percentages of bone marrow cells are indicated. (B) Increased CFU-GEMM in SCLtg mice. Bone marrow cells from wild-type, SCLtg/tg, and E2A+/− mice were plated in semisolid media, and colonies were scored 7 days later. The average numbers of CFU per femur are indicated.

Ectopic SCL expression mirrors a partial loss of E2A function in early B-cell progenitors.

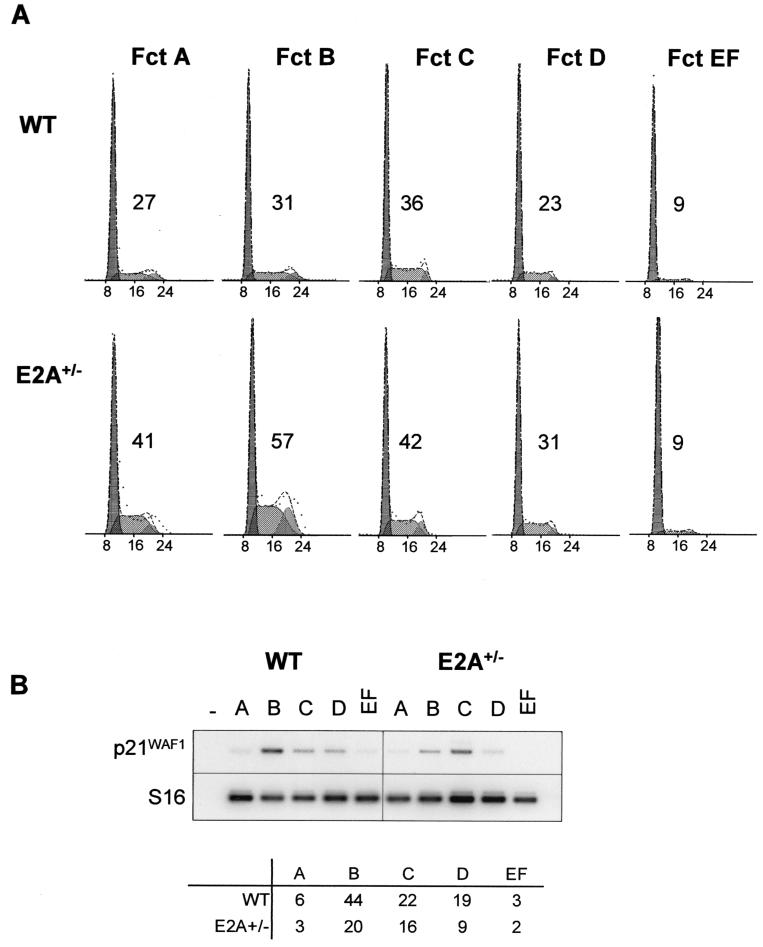

The decrease of pro-B cells in SCLtg/tg mice mirrors that reported in mice lacking one functional E2A allele, as assessed by flow cytometry analysis (57). We therefore quantified immature B-cell progenitors (WW-IC) in E2A+/− mice and found that they were decreased to the same extent as that observed in SCLtg/tg mice (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, E2A+/− bone marrow also exhibits an increase in B220− CD11b− SP cells as assessed by Hoechst 33342 staining (Fig. 5A), albeit lower than that observed in SCLtg/tg mice, indicating that the decrease in WW-IC results from a specific block in B lineage specification in these mice. We also performed cell cycle analysis within purified B-cell precursors (A to EF), in order to assess whether the decrease in B cells could be due to decreased cell cycling (Fig. 6). Surprisingly, cell cycling was significantly increased in pro-B cells lacking one functional E2A allele compared to in cells from wild-type littermates, indicating that E2A normally restrains pro-B and immature pre-B cells from cycling. Since it has been previously reported that p21waf/cip1 transcription depends on E47 activity in fibroblasts, we investigated p21waf/cip1 mRNA levels in B-cell subpopulations. Here we show that p21waf/cip1 mRNA levels in B-cell fractions correlate with E2A levels (i.e., p21waf/cip1 is high in fractions B to D and low in fractions A and EF). Furthermore, loss of one E2A allele results in a twofold decrease of p21walf/cip1 mRNA levels in fractions B and D, correlating with a near twofold increase in the number of cycling cells in these fractions. Together, our observations are consistent with the view that E2A controls p21waf/cipl levels in B cells and exerts an antiproliferative function.

FIG. 6.

Partial loss of E2A function increases the proliferation of pro-B cells. (A) Fractions A to EF were purified by flow cytometry from wild-type (WT) and E2A+/− bone marrows and analyzed for DNA content by using propidium iodide. Percentages of cells in the G2/M+S phase are indicated. (B) E2A level regulates p21waf/cip1 expression. Bone marrow B-cell fractions were purified by flow cytometry from wild-type and E2A+/− mice, and gene expression was investigated by RT-PCR. Hybridization signals were measured with the ImageQuant software and normalized for the amount of cDNA by using S16 as a control.

Ectopic SCL expression alters E2A DNA binding activity.

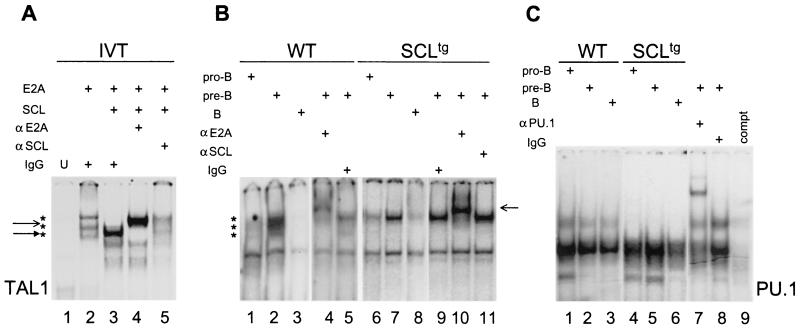

Previous in vitro studies have shown that E2A/SCL heterodimers can act as transcriptional transactivators within large multimeric complexes or as dominant-negative regulators of E2A homodimer activity (9, 21, 22, 36), depending on the cellular context and target genes. Moreover, the DNA binding activity of E2A/SCL heterodimers as well as E2A homodimers depends on posttranslational modifications of these proteins (38, 49). We therefore investigated the consequences of ectopic SCL expression on E2A DNA binding in developing B cells by using nuclear extracts from primary pro-B (fractions A, B, and C), pre-B (fraction D), and mature B (fractions EF) cells with the TAL1 probe. The TAL1 consensus sequence proved to be a high-affinity binding site for E2A/SCL heterodimers (Fig. 7A, lanes 3 to 5), which also recruits E2A homodimers, albeit with lower affinity (Fig. 7A, lane 2) (20). We also used a PU.1 probe to monitor the amount of nuclear extracts in each fraction (Fig. 7C). In nuclear extracts from wild-type pro-B and pre-B cells, at least three different complexes were formed on a TAL1 probe (Fig. 7B, lanes 1 and 2). All three complexes were supershifted by the addition of an anti-E2A antibody, but not by control IgG (Fig. 7B, lanes 4 and 5), indicating that they contain E2A proteins. These different complexes comigrated with those observed by using in vitro-translated E2A gene products, indicating that they may result from the association of different alternatively spliced products of the E2A gene (E12 and E47). While PU.1 DNA binding activities were elevated in all fractions (Fig. 7C), E2A DNA binding levels increased from the pro-B to pre-B stages (Fig. 7B, lanes 1 and 2, respectively) and then decreased at the B-cell stage (Fig. 7B, lane 3), correlating with variations in both mRNA and protein levels observed in Fig. 1B and 2. Finally, in mature B cells, only one E2A-containing complex was observed, indicating a developmental switch of E2A complexes, consistent with previous reports with B-cell lines (23).

FIG. 7.

Ectopic SCL expression partially inhibits E2A DNA binding activity. (A) Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed on the TAL1 consensus probe by using in vitro-translated (IVT) proteins as indicated. Stars indicate E2A complexes, a, solid arrow points to the E2A-SCL complex, and an open arrow points to E2A and SCL supershifts. U, unprogrammed reticulocyte lysates. (B) Pro-B (lanes 1 and 6), pre-B (lanes 2, 4, 5, 7, and 9 to 11), and B (lanes 3 and 8) cells were sorted by flow cytometry from wild-type (WT) or SCLtg bone marrows. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed with the TAL1 consensus probe. Anti-E2A and anti-SCL antibodies or control IgG was used for supershift experiments as indicated (lanes 4 to 5 and 9 to 10). (C) Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed on a PU.1 binding sequence by using pro-B, pre-B, and B-cell nuclear extracts prepared from wild-type and SCLtg bone marrows as in panel B. Anti-PU.1 antibody, control IgG, or cold competitor (compt.) was added as indicated (lanes 7 to 9).

Consequently to enforced SCL expression, E2A binding activity was altered, and only the most slowly migrating complex is detected (Fig. 7B, lanes 6 to 11). As observed with normal mice, binding was highest in pre-B cells and decreased in mature B cells. This complex was supershifted by the addition of an anti-E2A antibody (lane 10), but not by an anti-human SCL antibody (lane 11), indicating that it contains E2A, but not the SCL transgene. This result indicates that E2A/SCL heterodimers do not bind DNA in B cells, but greatly alter DNA binding by E2A homodimers, as shown by changes in the profiles of protein complexes formed on the TAL1 probe. These data correlate with previously reported results that indicate that SCL acts as a dominant-negative regulator of E2A DNA binding and transcriptional activities (13, 18, 22). We further reveal that only a subset of E2A-containing complexes are inhibited by SCL in B cells. Finally, the lack of E2A/SCL heterodimers on the probe suggests that the levels of the SCL transgene are either low or are subject to posttranslational modifications that are not permissive for DNA binding (38).

Inhibition of B-cell differentiation by SCL in vivo is facilitated by E2A haplo-insufficiency.

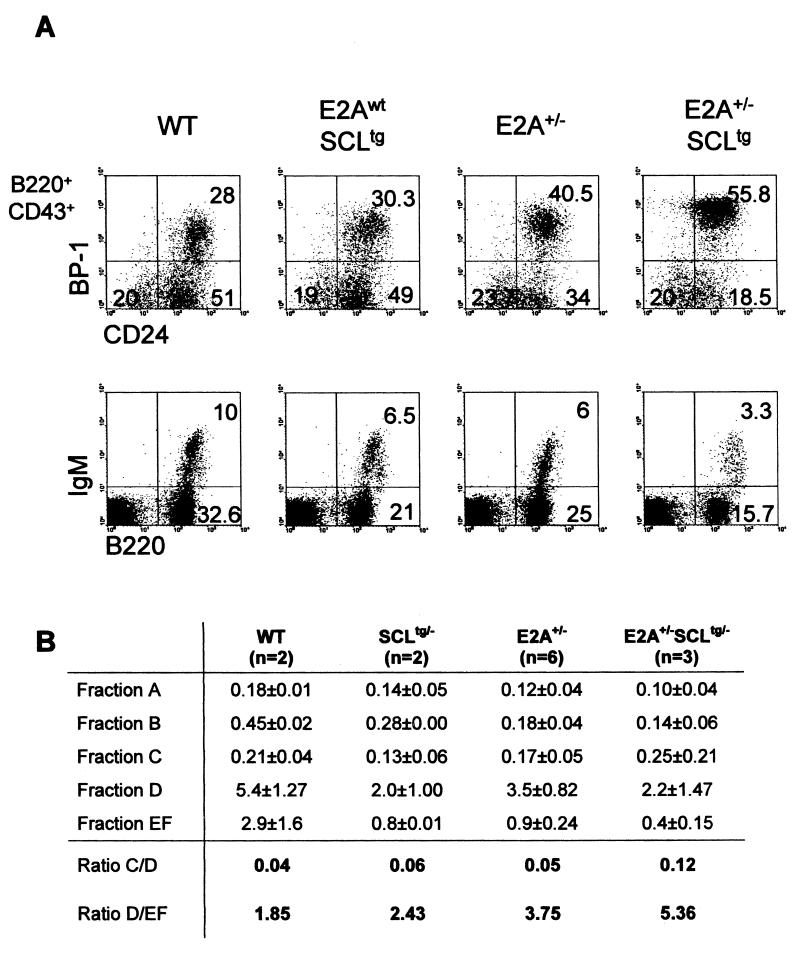

Side-by-side comparison of SCLtg and E2A+/− mice indicates that pre-pro-B cells (WW-IC) are decreased to the same extent (Fig. 4A), while anomalies at later stages are more severe in E2A+/− mice. First, cell cycle deficiency in B-cell populations is more severe in E2A+/− mice (Fig. 6) than in SCLtg mice (data not shown). Second, the transition from pre-B to mature B cells (Fig. 8A), as assessed by the D/EF ratio (Fig. 8B), is inhibited to a greater extent in E2A+/− mice. Third, SCLtg mice show a significant decrease in cell numbers in all B lineage fractions, while E2A insufficiency causes decreased cell numbers in all fractions except fraction C. In E2A+/− mice, fraction C showed an increase in percentage (Fig. 8A), and the total number of cells was almost normal (Fig. 8B). Since the C/D ratio was normal in E2A+/− mice, these observations suggest that the accumulation in fraction C was not due to an inability of E2A+/− cells to progress to the next stage. Because cell cycling is increased in fractions B and C (Fig. 6), we surmised that the normal number of cells in fraction C is a consequence of increased proliferation. Thus, E2A activity controls B lineage specification, cell number in fraction C, and progression to the IgM+ stage.

FIG. 8.

Ectopic SCL expression enhances the B-cell deficiency of E2A+/− mice. (A) Bone marrow B cells from wild-type (WT), SCL transgenic (E2Awt SCLtg), E2A heterozygous (E2A+/−), and E2A+/−SCLtg littermates (4 weeks old) were analyzed by flow cytometry for B-cell markers. Upper panels are gated on the B220+ CD43+ subset, and the percentages of populations A, B, and C are indicated in each quadrant. The results are representative of three independent litters. (B) Absolute numbers of cells in fractions A to EF were calculated per femur for each mouse, and the averages of three independent litters are indicated.

The observed differences at later stages in SCLtg/tg mice compared to E2A+/− mice could be due to the fact that SCL levels driven off the SIL promoter are not sufficient to inhibit E2A function at these stages. Indeed, the SCL protein level is low, as assessed by Western blotting (data not shown). We therefore assessed the possibility that SCL may further inhibit E2A function in mice lacking one functional E2A allele and crossed mice carrying one copy of the SCL transgene with E2A+/− mice (Fig. 8). Cell cycle analysis confirmed the effect of E2A haplo-insufficiency on B-cell cycle, as shown in Fig. 6A; this effect was not enhanced by the SCL transgene (data not shown). In contrast, the imbalance in the D/EF ratio was more severely affected in SCLtg E2A+/− mice than in E2A+/− littermates (Fig. 8), suggesting that SCL inhibits E2A function at this stage only when E2A dosage is decreased. As a consequence, the total number of IgM+ cells was severely decreased in SCLtg E2A+/− mice as compared to single heterozygote littermates (Fig. 8B). Together, the results indicate that the SCL transgene inhibits E2A function in B-cell differentiation, but not in cell cycle regulation, and reveal that different mechanisms underlie these two properties of E2A.

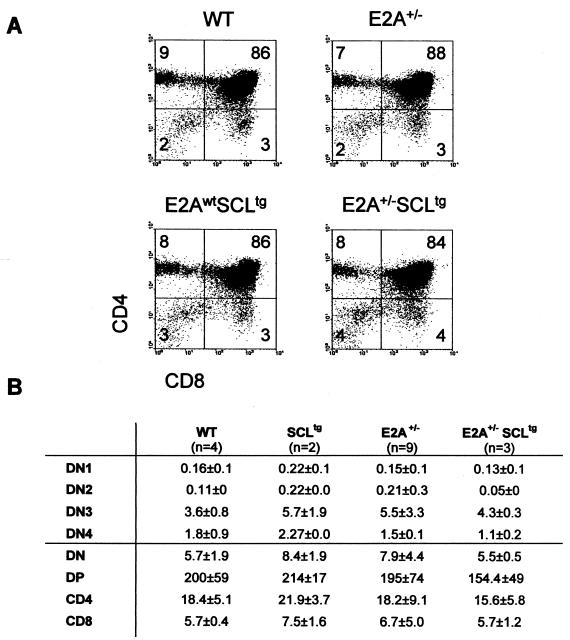

Our previous work indicates that T-cell differentiation was not affected in SCLtg mice (1, 16) and that inhibition of thymocyte development requires a collaboration between SCL and LMO1/2 (1, 16, 26). Because E2A+/− SCLtg mice show a more severe B-cell deficiency, we assessed thymocyte development in these mice. As shown in Fig. 9, CD4 and CD8 double-positive and single-positive cells develop normally in E2A+/−, SCLtg, or E2A+/− SCLtg mice. Since CD4 is an E2A or HEB target in the thymus (9, 16, 43), this observation suggests that the level of SCL protein in the SIL-SCL transgenic mice is not sufficient to inhibit E2A or HEB function in the thymus or, alternatively, that the collaboration of LMO1/2 is required to inhibit E2A or HEB function in thymocytes.

FIG. 9.

A partial loss of E2A function does not alter T-cell lineage differentiation. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of thymocytes from wild-type (WT), SCL transgenic (E2Awt SCLtg), E2A heterozygous (E2A+/−), and SCLtg E2A+/− littermates (4 weeks old) was performed with CD4 and CD8 antibodies. Percentages are indicated in each quadrant. The results are representative of three independent litters. (B) Absolute numbers of cells in different subsets were calculated per thymus, and the averages of three independent litters are indicated.

DISCUSSION

SCL is expressed in multipotent hematopoietic precursors (7, 17, 31, 39) and in long-term repopulating cells. In differentiating thymocytes, we have previously reported that SCL expression persists until the DN3 stage (16). Here we show that in the B lineage, SCL expression is turned off at the early pro-B stage (fraction A). Constitutive SCL expression in the bone marrow leads to a dose-dependent block at the B-cell commitment step, as revealed by limiting dilution analysis of WW-IC and flow cytometry analysis. Interestingly, the number of bone marrow Lin− SP cells was increased in SCL transgenic mice, indicating that the decrease of WW-IC does not result from a global decrease of the stem cell compartment, but rather results from a specific block of B-cell commitment.

SCL inhibits E2A function.

The inhibition of B-cell development could be due to several mechanisms. Given that SCL heterodimerizes with E2A and that E2A homodimers are important for B-cell development, the B-cell phenotype observed in SCL transgenic mice could be due to an inhibition of E2A function. Alternatively, SCL could affect B cells through pathways that are E2A independent.

The decrease in pre-pro-B cells (WW-IC) observed in the bone marrow of SCLtg/tg mice resembles that of E2A+/− mice, suggesting that the two genes function in the same pathway. Moreover, we show that ectopic SCL expression alters E2A DNA binding activity. Previous work with in vitro-translated proteins indicated that SCL decreases E2A homodimers binding to a μE5 probe (20). In SIL-SCL transgenic mice, the levels of the SCL transgene are relatively low, and it is unlikely that SCL can sequester E2A in an Id-like manner. Rather, our gel shift assays indicate that E2A DNA binding activity is altered in SCL transgenic mice, in favor of more slowly migrating complexes. Since the dosage of bHLH factors is critical for B-cell development, and both E12 and E47 are required for efficient commitment and maturation in the B lineage (4), our observations suggest that the inhibition of B-cell development in SCL transgenic mice is due to an altered stoichiometry of E2A-containing complexes on DNA. Furthermore, it is possible that the presence of SCL in E2A-containing complexes may alter their transcriptional output.

Additionally, the inhibition imposed by the SCL transgene on B-cell development may be E2A independent. SCL may, for example, induce the expression of target genes that, in turn, block B-cell maturation. Our observations, however, do not support this hypothesis. Indeed, SCL activates transcription through association with partners that include LMO1/2 and GATA factors. Since B cells do not express GATA-1 or other GATA factors, SCL is unlikely to activate the transcription of its target genes. In addition, the function of SCL may be more complex than anticipated. Our observations, nonetheless, favor the hypothesis that SCL inhibits some but not all E2A functions, as discussed below.

In order to directly address the possibility that SCL inhibits E2A function in vivo, we assessed the effect of the transgene when E2A activity is lowered. Our analysis confirmed that E2A is haplo-insufficient in the B lineage and showed that ectopic SCL expression in cells lacking one E2A allele further disrupts B-cell maturation. Taken together, these observations are consistent with the view that ectopic SCL expression inhibits E2A function, leading to impaired B-cell development.

E2A levels and cell cycling in the pro-B compartment.

Upon commitment into the B lineage, pro-B cells initiate D-J then V-DJ rearrangements in the IgH locus. In-frame rearranged Ig heavy chains associate with invariant light chains and signaling molecules to form the pre-B-cell receptor (pre-BCR). Signaling through the pre-BCR drives the proliferation of large pre-B cells and induces IgL chain gene rearrangement, allowing for progression to the IgM+ stage. Thus, the pro-B to pre-B transition is a critical checkpoint in B-cell development. While the importance of E2A in B-cell differentiation is well established, the role of E2A in B-cell proliferation has been a matter of debate. A recent study suggests that ectopic E2A expression promotes cell cycle progression in the human pre-B-cell line 697 (56), whereas other studies reported an antiproliferative function for E2A. In NIH 3T3 cells, expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21waf/cip1, which prevents cell cycle progression, is induced by E47. Furthermore, in transient transfection assays, p21 promoter activity depends on the integrity of three E boxes that are most proximal to the transcription start site, suggesting that p21 is a target of transcription regulation by E2A (37). Although informative, studies of cell lines are not directly relevant to normal physiological conditions. Our observations indicate that E2A haplo-insufficiency causes an increase in cell proliferation in both pro-B and pre-B cells, correlating with a twofold decrease in p21 mRNA levels. Interestingly, B lineage cells rearrange the IgH and IgL loci at these two developmental stages, consistent with the notion that Ig gene rearrangements preferentially occur in G0-G1-arrested cells. Taken together, our observations unravel a novel biological function for E2A in controlling B-cell maturation. Cell cycle regulation is likely to be complex, and E2A may control the transcription of more than one cell cycle gene or may even control cell cycling through functions that differ from its transcriptional activity. While the SCL transgene exacerbates E2A insufficiency in B-cell differentiation, it does not have an impact on E2A antiproliferative function. This observation suggests that E2A-containing complexes that specify B-cell identity are perturbed by the SCL transgene, while those involved in cell cycle control are not.

A gradient of E2A activity in B-cell development.

E2A proteins regulate the expression of numerous B-cell-specific genes required for pre-BCR and BCR expression that control the progression from late pro-B to the IgM+ stage (44, 48). E2A-deficient bone marrow cells lack mb-1, λ5, CD19, and Rag-1, while TdT and μ0 are present, suggesting that B-cell development is blocked at a stage that precedes Ig gene rearrangement and, possibly, at the B commitment stage (3, 50, 59). It is shown here that mice lacking one functional E2A allele exhibit a severe decrease in the earliest detectable B-cell progenitor, the WW-IC. The Lin− SP population was increased, indicating that the stem cell compartment was either increased or not affected, but commitment into the B lineage is impaired. Our results are therefore consistent with a crucial role for E2A at the B commitment step. Interestingly, ectopic SCL expression also blocks B-cell development at the same stage, in a dose-dependent manner. Thus, homozygous SIL-SCL transgenic mice present a more severe phenotype than heterozygote SCL transgenic mice and reproduce the deficiency observed in E2A+/− mice. These observations indicate that the level of SCL protein attained in SCLtg/tg mice is sufficient to inhibit the activity of one E2A allele in these primitive progenitors.

We observed an increase in E2A protein levels from fraction A to fraction D, in direct correlation with an increase of E2A targets (i.e., RAG-1), suggesting that E2A activity increases at the pro-B-to-pre-B transition. Since SCL transgene expression remains invariant in the different B-cell populations, our observations suggest that this level was sufficient to interfere with B lineage commitment, but not sufficient to perturb later maturation stages that are also controlled by E2A. Indeed, in mice lacking one functional E2A allele, ectopic SCL expression exacerbates the effect of E2A deficiency, and a higher proportion of cells accumulate at the pro-B-to-pre-B transition point. In these mice, SCL also affects the maturation of IgM− to IgM+ populations, because the assembly of surface IgM is dependent on E2A function as well. Thus, E2A controls three major checkpoints in B-cell development: commitment into the B lineage, the pro-B-to-pre-B transition controlled by the pre-BCR, and the progression to the mature B stage (IgM+) when cell fate is determined by expression of a functional BCR. Our observations indicate that the step involving commitment into the B lineage is more sensitive to fluctuations in E2A activity than later developmental stages. As a consequence, B cells that escape the initial block imposed by the SCL transgene are able to mature normally, not because the transgene is shut off at these stages, but because E2A activity is upregulated as cells progress to the pre-B stage. We also show that E47 is preferentially upregulated at the pre-B stage, consistent with an important function for E47 in B-cell maturation (4)

E2A gradient in B versus T lineage.

Together, our results indicate that SCL expression has to be turned off at the earliest pro-B stage in order to allow B-cell differentiation to proceed. In contrast, T lineage differentiation is not affected by ectopic SCL expression in either E2Awt or E2A+/− mice (1, 16; this report), indicating that the SCL level driven by the SIL promoter is not sufficient to inhibit E2A and HEB function in thymocytes. In T cells, collaboration with SCL partners such as LMO proteins is necessary to inhibit E protein function and to alter T-cell differentiation (9, 16). These observations are consistent with the finding that E2A functions with HEB in driving thymocyte development (43, 57). Furthermore, our observations suggest that B-cell commitment is more sensitive to bHLH dosage than T-cell lineage commitment, consistent with a model of cell fate determination in the lymphoid lineages in which B- versus T-cell fate is dependent on the level of E2A activity (8). This model, based on Notch1 signaling studies, implies that a reduction in E2A function in the common lymphoid precursor is permissive for the T-cell lineage, but not for the B-cell lineage, which requires an intact E2A activity. Our results suggest that SCL downregulation may be another important event that regulates E2A activity and determines cell fate in primitive lymphoid progenitors.

Several types of human T-ALL involve the aberrant expression of genes coding for bHLH transcription factors, such as SCL, Lyl-1, Tal-2 (reviewed in references 5, 28, and 32), and BHLH1 (53). Aberrant SCL expression is also associated with several murine thymomas (5, 29). It has therefore been proposed that leukemogenesis results in all cases from a partial inhibition of E2A function in T cells (16, 32). Indeed, Id transgenic mice as well as E2A-deficient mice develop T-ALL with high incidence (2). Although the molecular mechanism remains to be determined, these observations suggest that E2A has a tumor suppressor function in developing T cells. Such a role has not been described in B cells, although disruption of one E2A allele is involved in two chromosomal translocations encountered in human B-ALL. The t(1;19) and the t(17;19) translocations result in the expression of E2A-PBX and E2A-HLF fusion proteins, respectively. In both cases, the C-terminal transactivation domain of E2A is fused to the DNA binding and dimerization domains of PBX or HLF transcription factors. Since E2A-PBX and E2A-HLF do not bind the same DNA motifs, they may regulate different sets of genes. It has therefore been proposed that their leukemogenic activity may be caused, at least in part, by a dominant-negative inhibition of E2A activity (19) or a disruption of non-DNA binding functions of E2A. In addition to these anomalies, our observations indicate that loss of one E2A allele causes hyperproliferation in the pro-B compartment and, consequently, may contribute to leukemogenesis. In contrast to E2A, SCL gene alteration has not been reported in either human or murine B-ALL. Since the locus is transcriptionally active when recombinase activity starts (fraction A), it is possible that the same rearrangements occur in B cells as in human T-ALL. Since SCL does not affect E2A-dependent cell cycle control, our observations suggest that such illegitimate rearrangements may not provide a proliferative advantage to the cell, albeit they are sufficient for B-cell differentiation arrest.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Tessier for assistance with flow cytometry and cell sorting.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Canadian Institute for Health Research (T.H.) and a postdoctoral fellowship from the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (S.H.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aplan, P. D., C. A. Jones, D. S. Chervinsky, X. Zhao, M. Ellsworth, C. Wu, E. A. McGuire, and K. W. Gross. 1997. An scl gene product lacking the transactivation domain induces bony abnormalities and cooperates with LMO1 to generate T-cell malignancies in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 16:2408–2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bain, G., I. Engel, E. C. Robanus Maandag, H. P. J. te Riele, J. R. Voland, L. L. Sharp, J. Chun, B. Huey, D. Pinkel, and C. Murre. 1997. E2A deficiency leads to abnormalities in αβ T-cell development and to rapid development of T-cell lymphomas. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:4782–4791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bain, G., E. C. Maandag, D. J. Izon, D. Amsen, A. M. Kruisbeek, B. C. Weintraub, I. Krop, M. S. Schlissel, A. J. Feeney, and M. van Roon. 1994. E2A proteins are required for proper B cell development and initiation of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements. Cell 79:885–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bain, G., M. E. Robanus, H. P. J. te Riele, A. J. Feeney, A. Sheehy, M. Schlissel, S. A. Shinton, R. R. Hardy, and C. Murre. 1997. Both E12 and E47 allow commitment to the B cell lineage. Immunity 6:145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Begley, C. G., and A. R. Green. 1999. The SCL gene: from case report to critical hematopoietic regulator. Blood 93:2760–2770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benezra, R. 1994. An intermolecular disulfide bond stabilizes E2A homodimers and is required for DNA binding at physiological temperatures. Cell 79:1057–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brady, G., F. Billia, J. Knox, T. Hoang, I. R. Kirsch, E. B. Voura, R. G. Hawley, R. Cumming, M. Buchwald, and K. Siminovitch. 1995. Analysis of gene expression in a complex differentiation hierarchy by global amplification of cDNA from single cells. Curr. Biol. 5:909–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busslinger, M., S. L. Nutt, and A. G. Rolink. 2000. Lineage commitment in lymphopoiesis. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12:151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chervinsky, D. S., X.-F. Zhao, D. H. Lam, M. Ellsworth, K. W. Gross, and P. D. Aplan. 1999. Disordered T-cell development and T-cell malignancies in SCL LMO1 double-transgenic mice: parallels with E2A-deficient mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:5025–5035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chomczynski, P., and N. Sacchi. 1987. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 162:156–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen-Kaminsky, S., L. Maouche-Chretien, L. Vitelli, M. A. Vinit, I. Blanchard, M. Yamamoto, C. Peschle, and P. H. Romeo. 1998. Chromatin immunoselection defines a TAL-1 target gene. EMBO J. 17:5151–5160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins, L. S., and K. Dorshkind. 1987. A stromal cell line from myeloid long-term bone marrow cultures can support myelopoiesis and B lymphopoiesis. J. Immunol. 138:1082–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldfarb, A. N., and K. Lewandowska. 1995. Inhibition of cellular differentiation by the SCL/tal oncoprotein: transcriptional repression by an Id-like mechanism. Blood 85:465–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodell, M. A., K. Brose, G. Paradis, A. S. Conner, and R. C. Mulligan. 1996. Isolation and functional properties of murine hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 183:1797–1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardy, R. R., C. E. Carmack, S. A. Shinton, J. D. Kemp, and K. Hayakawa. 1991. Resolution and characterization of pro-B and pre-pro-B cell stages in normal mouse bone marrow. J. Exp. Med. 173:1213–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herblot, S., A. M. Steff, P. Hugo, P. D. Aplan, and T. Hoang. 2000. SCL and LMO1 alter thymocyte differentiation: inhibition of E2A-HEB function and pre-Talpha chain expression. Nat. Immunol. 1:138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoang, T., E. Paradis, G. Brady, F. Billia, K. Nakahara, N. N. Iscove, and I. R. Kirsch. 1996. Opposing effects of the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor SCL on erythroid and monocytic differentiation. Blood 87:102–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofmann, T. J., and M. D. Cole. 1996. The TAL1/Scl basic helix-loop-helix protein blocks myogenic differentiation and E-box dependent transactivation. Oncogene 13:617–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honda, H., T. Inaba, T. Suzuki, H. Oda, Y. Ebihara, K. Tsuiji, T. Nakahata, T. Ishikawa, Y. Yazaki, and H. Hirai. 1999. Expression of E2A-HLF chimeric protein induced T-cell apoptosis, B-cell maturation arrest, and development of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 93:2780–2790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu, H.-L., L. Huang, J. T. Tsan, W. Funk, W. E. Wright, J.-S. Hu, R. E. Kingston, and R. Baer. 1994. Preferred sequences for DNA recognition by the TAL1 helix-loop-helix proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:1256–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu, H. L., I. Wadman, and R. Baer. 1994. Formation of in vivo complexes between the TAL1 and E2A polypeptides of leukemic T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:3181–3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu, H. L., I. Wadman, J. T. Tsan, and R. Baer. 1994. Positive and negative transcriptional control by the TAL1 helix-loop-helix protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:5947–5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobs, Y., C. Vierra, and C. Nelson. 1993. E2A expression, nuclear localization, and in vivo formation of DNA- and non-DNA-binding species during B-cell development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:7321–7333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kee, B. L., and C. Murre. 1998. Induction of early B cell factor (EBF) and multiple B lineage genes by the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor E12. J. Exp. Med. 188:699–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim, D., X. C. Peng, and X. H. Sun. 1999. Massive apoptosis of thymocytes in T-cell-deficient Id1 transgenic mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:8240–8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larson, R. C., I. Lavenir, T. A. Larson, R. Baer, A. J. Warren, I. Wadman, K. Nottage, and T. H. Rabbitts. 1996. Protein dimerization between Lmo2 (Rbtn2) and Tal1 alters thymocyte development and potentiates T cell tumorigenesis in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 15:1021–1027. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, Y. S., R. Wasserman, K. Hayakawa, and R. R. Hardy. 1996. Identification of the earliest B lineage stage in mouse bone marrow. Immunity 5:527–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Look, A. T. 1997. Oncogenic transcription factors in the human acute leukemias. Science 278:1059–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowsky, R., J. F. DeCoteau, A. H. Reitmair, R. Ichinohasama, W. F. Dong, Y. Xu, T. W. Mak, M. E. Kadin, and M. D. Minden. 1997. Defects of the mismatch repair gene MSH2 are implicated in the development of murine and human lymphoblastic lymphomas and are associated with the aberrant expression of rhombotin-2 (Lmo-2) and Tal-1 (SCL). Blood 89:2276–2282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu, L., G. Smithson, P. W. Kincade, and D. G. Osmond. 1998. Two models of murine B lymphopoiesis: a correlation. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:1755–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mouthon, M. A., O. Bernard, M. T. Mitjavila, P. H. Romeo, W. Vainchenker, and D. Mathieu-Mahul. 1993. Expression of tal-1 and GATA-binding proteins during human hematopoiesis. Blood 81:647–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murre, C. 2000. Intertwining proteins in thymocyte development and cancer. Nat. Immunol. 1:97–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nutt, S. L., B. Heavey, A. G. Rolink, and M. Busslinger. 1999. Commitment to the B-lymphoid lineage depends on the transcription factor Pax5. Nature 401:556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ono, Y., N. Fukuhara, and O. Yoshie. 1998. TAL1 and LIM-only proteins synergistically induce retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 expression in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia by acting as cofactors for GATA3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:6939–6950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Riordan, M., and R. Grosschedl. 1999. Coordinate regulation of B cell differentiation by the transcription factors EBF and E2A. Immunity 11:21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park, S. T., and X. H. Sun. 1998. The Tal1 oncoprotein inhibits E47-mediated transcription. Mechanism of inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 273:7030–7037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prabhu, S., A. Ignatova, S. T. Park, and X.-H. Sun. 1997. Regulation of the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 by E2A and Id proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:5888–5896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prasad, K. S., and S. J. Brandt. 1997. Target-dependent effect of phosphorylation on the DNA binding activity of the TAL1/SCL oncoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 272:11457–11462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pulford, K., N. Lecointe, K. Leroy-Viard, M. Jones, D. Mathieu-Mahul, and D. Y. Mason. 1995. Expression of TAL-1 proteins in human tissues. Blood 85:675–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rabbitts, T. H. 1998. LMO T-cell translocation oncogenes typify genes activated by chromosomal translocations that alter transcription and developmental processes. Genes Dev. 12:2651–2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robb, L., I. Lyons, R. Li, L. Hartley, F. Kontgen, R. P. Harvey, D. Metcalf, and C. G. Begley. 1995. Absence of yolk sac hematopoiesis from mice with a targeted disruption of the scl gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:7075–7079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rolink, A. G., S. L. Nutt, F. Melchers, and M. Busslinger. 1999. Long-term in vivo reconstitution of T-cell development by Pax5-deficient B-cell progenitors. Nature 401:603–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sawada, S., and D. R. Littman. 1993. A heterodimer of HEB and an E12-related protein interacts with the CD4 enhancer and regulates its activity in T-cell lines. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:5620–5628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schlissel, M., A. Voronova, and D. Baltimore. 1991. Helix-loop-helix transcription factor E47 activates germ-line immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene transcription and rearrangement in a pre-T-cell line. Genes Dev. 5:1367–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlissel, M. S., L. M. Corcoran, and D. Baltimore. 1991. Virus-transformed pre-B cells show ordered activation but not inactivation of immunoglobulin gene rearrangement and transcription. J. Exp. Med. 173:711–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen, C.-P., and T. Kadesch. 1995. B-cell-specific DNA binding by an E47 homodimer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:4518–4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shivdasani, R. A., E. L. Mayer, and S. H. Orkin. 1995. Absence of blood formation in mice lacking the T-cell leukaemia oncoprotein tal-1/SCL. Nature 373:432–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sigvardsson, M., M. O’Riordan, and R. Grosschedl. 1997. EBF and E47 collaborate to induce expression of the endogenous immunoglobulin surrogate light chain genes. Immunity 7:25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sloan, S. R., C. P. Shen, R. McCarrick-Walmsley, and T. Kadesch. 1996. Phosphorylation of E47 as a potential determinant of B-cell-specific activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:6900–6908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun, X. H. 1994. Constitutive expression of the Id1 gene impairs mouse B cell development. Cell 79:893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tudor, K.-S., K. J. Payne, Y. Yamashita, and P. W. Kincade. 2000. Functional assessment of precursors from murine bone marrow suggests a sequence of early B lineage differentiation events. Immunity 12:335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wadman, I. A., H. Osada, G. G. Grutz, A. D. Agulnick, H. Westphal, A. Forster, and T. H. Rabbitts. 1997. The LIM-only protein Lmo2 is a bridging molecule assembling an erythroid, DNA-binding complex which includes the TAL1, E47, GATA-1 and Ldb1/NLI proteins. EMBO J. 16:3145–3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang, J., S. N. Jani-Sait, E. A. Escalon, A. J. Carroll, P. J. de Jong, I. R. Kirsch, and P. D. Aplan. 2000. The t(14;21)(q11.2;q22) chromosomal translocation associated with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia activates the BHLHB1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3497–3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whitlock, C. A., and O. N. Witte. 1982. Long-term culture of B lymphocytes and their precursors from murine bone marrow. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79:3608–3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yan, W., A. Z. Young, V. C. Soares, R. Kelley, R. Benezra, and Y. Zhuang. 1997. High incidence of T-cell tumors in E2A-null mice and E2A/Id1 double-knockout mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:7317–7327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao, F., A. Vilardi, R. J. Neely, and J. K. Choi. 2001. Promotion of cell cycle progression by basic helix-loop-helix E2A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:6346–6357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhuang, Y., P. Cheng, and H. Weintraub. 1996. B-lymphocyte development is regulated by the combined dosage of three basic helix-loop-helix genes, E2A, E2-2, and HEB. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:2898–2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhuang, Y., C. G. Kim, S. Bartelmez, P. Cheng, M. Groudine, and H. Weintraub. 1992. Helix-loop-helix transcription factors E12 and E47 are not essential for skeletal or cardiac myogenesis, erythropoiesis, chondrogenesis, or neurogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:12132–12136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhuang, Y., P. Soriano, and H. Weintraub. 1994. The helix-loop-helix gene E2A is required for B cell formation. Cell 79:875–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]