Abstract

The integrin α6β4 has been implicated in two apparently contrasting processes, i.e., the formation of stable adhesions, and cell migration and invasion. To study the dynamic properties of α6β4 in live cells two different β4-chimeras were stably expressed in β4-deficient PA-JEB keratinocytes. One chimera consisted of full-length β4 fused to EGFP at its carboxy terminus (β4-EGFP). In a second chimera the extracellular part of β4 was replaced by EGFP (EGFP-β4), thereby rendering it incapable of associating with α6 and thus of binding to laminin-5. Both chimeras induce the formation of hemidesmosome-like structures, which contain plectin and often also BP180 and BP230. During cell migration and division, the β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 hemidesmosomes disappear, and a proportion of the β4-EGFP, but not of the EGFP-β4 molecules, become part of retraction fibers, which are occasionally ripped from the cell membrane, thereby leaving “footprints” of the migrating cell. PA-JEB cells expressing β4-EGFP migrate considerably more slowly than those that express EGFP-β4. Studies with a β4-EGFP mutant that is unable to interact with plectin and thus with the cytoskeleton (β4R1281W-EGFP) suggest that the stabilization of the interaction between α6β4 and LN-5, rather than the increased adhesion to LN-5, is responsible for the inhibition of migration. Consistent with this, photobleaching and recovery experiments revealed that the interaction of β4 with plectin renders the bond between α6β4 and laminin-5 more stable, i.e., β4-EGFP is less dynamic than β4R1281W-EGFP. On the other hand, when α6β4 is bound to laminin-5, the binding dynamics of β4 to plectin are increased, i.e., β4-EGFP is more dynamic than EGFP-β4. We suggest that the stability of the interaction between α6β4 and laminin-5 is influenced by the clustering of α6β4 through the deposition of laminin-5 underneath the cells. This clustering ultimately determines whether α6β4 will inhibit cell migration or not.

INTRODUCTION

Keratinocytes adhere to the basement membrane by hemidesmosomes that serve as anchoring sites for the intermediate filament system and play a critical role in stabilizing the association of the dermis with the epidermis. The transmembrane components of hemidesmosomes comprise the laminin-5 (LN-5) binding integrin α6β4 and the bullous pemphigoid antigen (BP)180. These proteins are connected via the hemidesmosomal proteins plectin and BP230 to the keratin intermediate filament system (reviewed by Jones et al., 1998; Borradori and Sonnenberg, 1999).

Based on their structural constituents, two subtypes of hemidesmosomes are distinguished. Type I hemidesmosomes contain α6β4, plectin, BP180, and BP230 (Green and Jones, 1996), whereas type II hemidesmosomes contain only α6β4 and plectin (Uematsu et al., 1994). Recently, the tetraspanin CD151 was identified as another component of both type I and II hemidesmosomes (Sterk et al., 2000). Type I or classical hemidesmosomes are present in basal keratinocytes of squamous and complex epithelia (Nievers et al., 1999). Type II hemidesmosomes are found in intestinal epithelial cells and some other cultured epithelial cell types (Uematsu et al., 1994; Orian-Rousseau et al., 1996; Fontao et al., 1997). The association of type II hemidesmosomes with intermediate filaments is less robust than that of type I hemidesmosomes, which may imply a more dynamic regulation of their assembly.

The stability of type I hemidesmosomes is illustrated by their continued presence during mitosis (Riddelle et al., 1992; Baker and Garrod, 1993), thereby ensuring that cells with a strong proliferative potential remain present in the basal compartment of the skin. However, during wound healing, hemidesmosomes are disassembled to allow keratinocytes to migrate on a newly deposited LN-5 matrix (Martin, 1997; Decline and Rousselle, 2001). Several growth factors have been implicated in the regulation of the disassembly of hemidesmosomes, including the epidermal and hepatocyte growth factors (Mainiero et al., 1996; Trusolino et al., 2001). As a result of interaction of these growth factors with their cognate receptors, the β4 subunit is tyrosine phosphorylated and recruits the signaling adaptor protein Shc (Mainiero et al., 1996; Mariotti et al., 2001; Trusolino et al., 2001). Conceivably, the phosphorylation of β4 on tyrosine residues may prevent its incorporation into hemidesmosomes. Studies by Rabinovitz et al. (1999), however, have revealed that EGF receptor-mediated disruption of hemidesmosomes depends on the ability of this receptor to activate protein kinase C and may involve the direct phosphorylation of the β4 cytoplasmic domain on serine residues. In addition, there is evidence suggesting that α6β4 activates phosphoinositide 3-OH (PI-3) kinase (Shaw et al., 1997; Shaw, 2001) and interacts with the actin cytoskeleton in filopodia and lamellipodia (Rabinovitz et al., 1997, 1999). This ability of α6β4 to activate PI-3-kinase signaling has been connected to the promotion by this integrin of the migration and invasion of carcinoma cells (Rabinovitz and Mercurio, 1997; Shaw et al., 1997; Gambaletta et al., 2000; Hintermann et al., 2001). Activation of PI-3 kinase by α6β4 may also contribute to adhesion and spreading of keratinocytes via binding of α3β1 to LN-5 (Nguyen et al., 2000). Finally, it has been shown that proteolytic processing of the LN-5-α3 and -γ2 chains may determine whether this matrix protein supports stable adhesion or instead migration (Giannelli et al., 1997; Goldfinger et al., 1998). Taken together these data show that cell migration is regulated by both extrinsic (proteases) and intrinsic (signaling molecules) factors.

New insights into the dynamic properties of focal contacts have been provided by studying green fluorescent (GFP)-tagged integrin α or β subunits in live cells (Smilenov et al., 1999; Ballestrem et al., 2001; Laukaitis et al., 2001). To gain more information about the dynamics of hemidesmosomes, we expressed two different enhanced GFP (EGFP)-tagged β4 chimeras in β4-deficient PA-JEB keratinocytes (Schaapveld et al., 1998). In one, EGFP was fused to the carboxy-terminal end of the β4 cytoplasmic domain (β4-EGFP), and in the other the extracellular domain of β4 was replaced by EGFP (EGFP-β4), which made this chimera incapable of associating with the α6 subunit and thus of binding LN-5. However, independently of binding to ligand, it can still induce hemidesmosome formation through its interaction with the hemidesmosomal component plectin (Nievers et al., 1998, 2000).

We studied the formation of hemidesmosomes by these two chimeras by using time-lapse video microscopy. Our data indicate that hemidesmosomes containing either β4-EGFP or EGFP-β4 are both dynamic structures that are assembled and redistributed during cell migration and division. Furthermore, we show that as a result of binding of α6β4 to plectin, the binding of α6β4 LN-5 is stabilized, which inhibits cell migration and reduces the dynamics of α6β4. We thus provide novel insights into the role of the α6β4 integrin in migration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines

Immortalized β4-deficient keratinocytes have been derived from a patient with pyloric atresia associated with junctional epidermolysis bullosa (PA-JEB; Niessen et al., 1996; Schaapveld et al., 1998). Full-length β4 cDNA and a cDNA encoding a chimeric protein consisting of the extracellular and transmembrane domains of the interleukin 2 receptor (IL2R) fused to the cytoplasmic domain of β4 were stably expressed in PA-JEB cells by retroviral infection to generate PA-JEB/β4 (Sterk et al. 2001) and PA-JEB/IL2R-β4 (Nievers et al., 1998), respectively. PA-JEB/β4-EGFP, PA-JEB/EGFP-β4, and PA-JEB/β4R1281W-EGFP cells were generated as described below. All cells were maintained in keratinocyte serum-free medium (SFM; Life Technologies-BRL; Rockville, MD) supplemented with 50 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract, 5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 U/ml streptomycin. To stimulate hemidesmosome formation, cells were grown for 24 h in calcium-rich medium, consisting of HAM-F12 Nutrient Mixture (Life Technologies-BRL) and DMEM (Life Technologies-BRL) in a ratio of 1:3.

Plasmid Constructs and Generation of PA-JEB/β4-EGFP and PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 Keratinocytes

The chimeric β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 constructs were produced in pcDNA3. The β4-EGFP chimera consisted of the full-length human β4A sequence, a sequence encoding six glycine residues followed by EGFP (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The EGFP-β4 chimera consisted of the amino acid signal sequence of the β4 subunit, EGFP, and transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of human β4A integrin. Both constructs were generated by overlap PCR using the following sequences: β4 c-terminus/6*glycine, 5′-catgccgccgccgccgccgccagtttggaagaactgttggtc-3′; 6*glycine-EGFP, 5′-ggcggcggcggcggcggcatggtgagcaagggcgaggag-3′; β4 signal sequence-EGFP, 5′-ctcctcgcccttgctcaccatgcggtttgccaaggtcccaga-3′; EGFP-β4 transmembrane, 5′-catgccatggtcttgtacagctcgtccatgcc-3′. The two PCR products were digested with EcoRI and cloned into the corresponding site of the pcDNA3 vector. The β4R1281W-EGFP construct was generated by replacing a 5-kb EcoRI/EcoRV fragment from β4-EGFP cDNA with a corresponding fragment containing a CGG to TGG mutation in codon 1281 of β4 (Geerts et al., 1999). Subsequently, the EGFP-β4, β4-EGFP, and β4R1281W-EGFP cDNAs were released from pcDNA3 by digestion with EcoRI, and the resulting fragments were ligated into the corresponding site of the retroviral LZRS-IRES-zeo expression vector, a modified LZRS retroviral vector conferring resistance to zeocin (Kinsella and Nolan, 1996; van Leeuwen et al., 1997) to result in the LZRS-EGFP-β4-IRES-zeo, LZRS-β4-EGFP-IRES-zeo, and LZRS-β4R1281W-EGFP-IRES-zeo constructs, respectively. Correctness of the DNA constructs was verified by sequence analysis The retroviral constructs were transfected into the Phoenix packaging cell line (Kinsella and Nolan, 1996) by the calcium phosphate precipitation procedure, and after 2 days supernatants containing recombinant viruses were collected. Transduction of the recombinant viruses in PA-JEB cells was performed for 10 h at 37°C. PA-JEB cells expressing β4-EGFP, β4R1281W-EGFP, or EGFP-β4 were isolated by FACS, expanded, and analyzed.

Antibodies

The rat mAb GoH3 is a blocking antibody directed against the extracellular part of the integrin α6 subunit (Sonnenberg et al., 1987). The mouse mAb K20, anti-β1, was purchased from Biomeda (Foster City, CA). The mouse mAb 450–11A, directed against the cytoplasmic domain of β4 was from PharMingen International (San Diego, CA). The rabbit polyclonal antibody against the LN-5 α3 chain was a kind gift of Dr. R. Timpl (Max Planck Institut für Biochemie, Martinsried, Germany). The mouse mAbs 121, anti-plectin/HD1 (Hieda et al., 1992), and 233, anti-BP180 (Nishizawa et al., 1993), were generously provided by Dr. K. Owaribe (Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan). The human mAbs 5E and 10D against BP230 (Hashimoto et al., 1993) were a kind gift of Dr. T. Hashimoto (Kurume University, Kurume, Fukuoka, Japan). The mouse mAb TB30, against the extracellular domain of the interleukin-2-receptor (IL2R), was purchased from the Central Laboratory of the Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Mouse mAb 3C12, anti-ezrin, was from Lab Vision Corp. (Fremont, CA), mouse mAb RV202, anti-vimentin, was kindly provided by Dr. F. Ramaekers (University of Limburg, Maastricht, The Netherlands), mouse mAbs against α and β tubulins were from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO; clones B-5-1-2 and 2-28-33), mouse mAb KL-1, anti-keratin, was from Immunotech (Marseille, France), rabbit antiserum against human LN-5 (Marinkovich et al., 1992) was a kind gift of Dr. R. Burgeson (Cutanous Biology Research Center, Charlestown, MA). The mouse mAb P48, also known as 11B1.G4, was clustered as CD151 in the VI International Leukocyte Typing Workshop (Ashman et al., 1997). The mouse B34 mAb directed against GFP was purchased from BabCO (Richmond, CA).

The sheep anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase–coupled antibodies were purchased from Amersham Corp. (Arlington Heights, IL), Texas Red–conjugated goat anti-mouse rat or rabbit antibodies were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR), Texas Red– conjugated donkey anti-human antibodies and Cy-5–conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies and were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA).

Time-lapse Observations and Fluorescence Recovery after Photobleaching Experiments

Time-lapse observations were made in a tissue culture device at 37°C and viewed under a Leica TCS-NT confocal microscope (Deerfield, IL) equipped with argon/krypton laser. The krypton/argon laser was used to excite the EGFP-tagged proteins at 488 nm, and emissions above 515 nm were collected. Images of β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 were collected every 2–15 min for periods up to 4 h. Phase-contrast images of cells were taken during time-lapse observations to obtain the corresponding cell shape image.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments were performed by selecting a region of β4-EGFP or EGFP-β4 hemidesmosomes located at the cell periphery, and oval-shaped regions were bleached using the krypton/argon laser for 1 s at 100% power, resulting in a bleached spot of 1 μm diameter. Images were collected after bleaching every 15 s for 10 min. The fluorescence intensity in the bleached region of the β4-EGFP or EGFP-β4 hemidesmosome during 10 min of recovery was normalized to the fluorescence intensity measured in a nonbleached region. This procedure allowed us to account for the decreased fluorescence due to overall bleaching of the entire field as a result of image collection. Phase-contrast images of cells were taken during FRAP analysis to ensure that there was no significant change in cell shape and position during periods of observation. Imaging from live cells on our confocal system prohibits the collection of large numbers of images, so that reliable fitting of more than one component is not possible. In the inhibitor studies, antibodies (GoH3) were added at a concentration of 25 μg/ml 24 h before FRAP analysis.

Preparation of Laminin-5 Matrices

PA-JEB/β4-EGFP and PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 keratinocytes were grown to confluency in six-well tissue culture plates, washed three times with PBS, and incubated overnight at 4°C in PBS containing 20 mM EDTA and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Sigma). After incubation the cells were removed by forceful pipetting, and the remaining matrices were dissolved in SDS sample buffer. For Western analysis a fraction (¼) of the matrices in the well was loaded.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

PA-JEB/β4, PA-JEB/β4-EGFP, PA-JEB/EGFP-β4, and PA-JEB/IL2R-β4 keratinocytes grown on glass coverslips were washed and fixed with 1% (wt/vol) formaldehyde for 10 min. Fixed cells were washed twice with PBS and permeabilized in 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. Cells were rinsed with PBS and incubated in 2% (wt/vol) BSA in PBS for 1 h, followed by incubation with the primary antibody for 1 h. After washing twice with PBS, Texas Red– and Cy-5–conjugated secondary antibodies directed against mouse and rabbit immunoglobulins, respectively, were applied for another 1 h. Actin was labeled with phalloidin Alexa 568 at a 1:40 dilution. After washing twice with PBS, coverslips were mounted on microscope slides with Mowiol (Longin et al., 1993) and viewed under a Leica TCS-NT confocal laser-scanning microscope. All steps were performed at room temperature.

Western Blotting Analysis

PA-JEB/β4, PA-JEB/EGFP-β4, and PA-JEB/β4-EGFP keratinocytes were lysed in 1% (wt/vol) SDS, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), containing the proteinase inhibitors phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (1 mM), soybean trypsin inhibitor (10 μg/ml), and leupeptin (10 μg/ml). The protein extracts of 2 × 105 cells were loaded per lane on 10% polyacrylamide gels, separated by electrophoresis, and transferred to Immobilon-PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membranes were stained with Coomassie blue to indicate the markers, destained (45% methanol, 5% acetic acid in demineralized water), and blocked by incubation in 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST-buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.3% Tween-20) for 30 min at room temperature. Then, the membranes were incubated with the mouse primary antibodies B34 (anti-GFP) or 450–11A (anti-β4), diluted 1:500 in 0.5% dry milk in TBST, for 1 h at room temperature. After washing three times with TBST, the membranes were incubated with secondary sheep anti-mouse Ig-coupled horseradish peroxidase (1:5000 dilution) for an additional hour at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Corp.).

Measurement of Cell Motility

PA-JEB/EGFP-β4, PA-JEB/β4-EGFP, and PA-JEB/β4R1281W-EGF keratinocytes were grown to confluence on glass coverslips in keratinocyte-SFM. To assess the relative contribution of cell migration in the absence of proliferation, cells were treated with 10 μg/ml mitomycin C (Sigma Chemical) 2 h before wounding. A cell-free area was introduced by scraping the monolayer with a yellow pipette tip, followed by three washes with PBS to remove cell debris. Scratched areas were photographed at ×200 magnification. Cells were subsequently incubated at 37°C for 48 h in keratinocyte-SFM, and the wounded monolayers were photographed again. In the inhibitor studies, antibodies (GoH3) were added at a concentration of 25 μg/ml, 1 h before wounding.

RESULTS

β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 Induce the Assembly of Hemidesmosomes

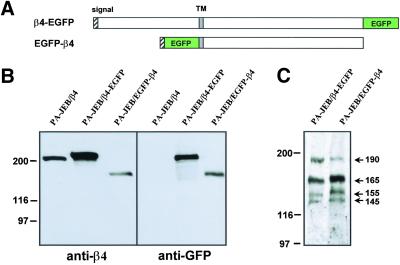

In previous studies using keratinocytes transfected with an IL2R-β4 chimera, it was shown that α6β4 can induce the formation of hemidesmosomes without binding to its ligand (Nievers et al., 1998, 2000). Under these circumstances hemidesmosome formation is driven by the cytoplasmic domain of the β4 subunit and is dependent on its association with plectin. To study ligand-dependent and -independent hemidesmosome formation in live cells, two different β4-EGFP chimeras were constructed. The β4-EGFP chimera consisted of EGFP fused to the carboxy-terminal end of the β4 cytoplasmic domain, whereas in the EGFP-β4 chimera the extracellular domain of β4 was replaced by EGFP (Figure 1A). The chimeras were introduced by retroviral transduction into β4-deficient PA-JEB keratinocytes to create stable cell lines. Both EGFP chimeras were expressed, and their molecular masses were as expected (Figure 1B). Introduction of the EGFP chimeras did not affect the expression of the other members of the integrin family at the cell surface, because FACS analysis demonstrated that the levels of α2, α3, α5, and β1 subunits were unaffected (unpublished data).

Figure 1.

(A) Diagram of β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 constructs. In β4-EGFP the complete β4 subunit was fused to EGFP and in EGFP-β4, the extracellular domain of the β4 subunit was replaced by EGFP. (B) Western blot analysis of β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 protein levels in PA-JEB/β4-EGFP and PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 keratinocytes. Whole cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting with monoclonal antibodies against β4 (450-11A) and GFP (B34). β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 are present as a single band of the expected molecular mass. (C). Western blot analysis of laminin-5 in matrices produced and deposited by PA-JEB/β4-EGFP and PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 keratinocytes. Matrices were solubilized, separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, and processed for Western blot analysis using anti–laminin-5 antiserum. The four major immunoreactive proteins of 190, 165, 155, and 145 kDa correspond to the unprocessed and processed forms of α3, and to the γ2 and β3 chains of laminin-5, respectively.

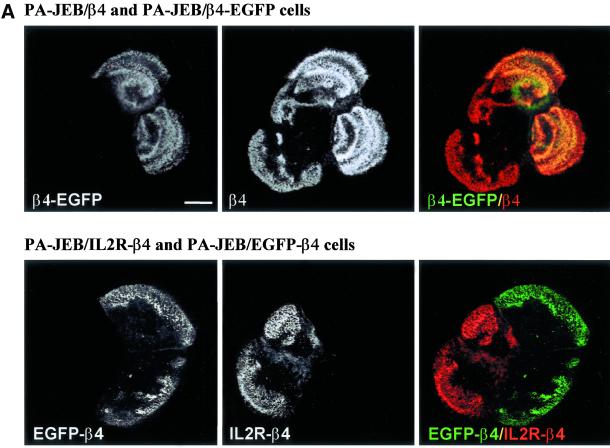

Fluorescence microscopy of PA-JEB cells expressing the β4-EGFP or EGFP-β4 chimera showed that both chimeras are able to induce the formation of hemidesmosome-like structures, the distribution pattern of which resembles that produced by the expression of β4 or IL2R-β4 in PA-JEB cells, respectively (Figure 2A). Furthermore, the hemidesmosome-like structures contain plectin, BP180, and BP230. β4-EGFP was always colocalized with patches of LN-5 deposited underneath the cells, whereas sometimes EGFP-β4 was not colocalized with LN-5 (Figure 2B). These results support the assumption that β4-EGFP when associated with α6 interacts with LN-5, whereas the EGFP-β4 chimera does not.

Figure 2.

(A) Similar localization of β4-EGFP and β4, and of EGFP-β4 and IL2R-β4. Top: PA-JEB/β4 and PA-JEB/β4-EGFP keratinocytes in a mixed culture were fixed and incubated with antibodies against the cytoplasmic domain of β4 (450–11A), followed by Texas red–conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG. Both β4 and β4-EGFP hemidesmosomes occur in a cauliflower-like staining pattern, and there is no difference between β4 and β4-EGFP hemidesmosomes. Bottom: PA-JEB/IL2R-β4 and PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 keratinocytes in a mixed culture were fixed, and the IL2R-β4 construct was labeled with antibodies directed against the IL2R part of the chimera (in the IL2R-β4 chimera, the extracellular part of β4, is replaced by the extracellular part of the IL2 receptor), followed by Texas red–conjugated secondary antibodies. β4-EGFP and IL2R-β4 that do not interact with LN-5 are mainly localized at the periphery of cells and the hemidesmosomes formed by them appeared to be more clustered than those formed by β4-EGFP or β4. No differences can be observed between EGFP-β4 and IL2R-β4 hemidesmosomes. Composite images were generated by superimposition of the green and red signals. Areas of overlap appear yellow in the images. (B) Colocalization of β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 with the hemidesmosomal components BP180, BP230, plectin, and LN-5. PA-JEB keratinocytes expressing β4-EGFP (left panel) or EGFP-β4 (right panel) were fixed and immunostained for BP180, BP230, plectin, or LN-5. Composite images were generated by superimposition of the green and red signals. Areas of overlap appear yellow in the images. Both chimeras are colocalized with the hemidesmosomal components BP180, BP230, plectin, and LN-5. Only β4-EGFP is colocalized with LN-5. Bar, 10 μm.

Analysis of the matrices deposited by β4-EGFP– and EGFP-β4–expressing cells by immunoblotting, using polyclonal anti-LN-5 antibodies, confirmed the presence of LN-5 in these matrices and furthermore showed that the α3 chain of a proportion of laminin-5 had been proteolytically processed. The ratio of unprocessed (190 kDa) and processed α3 (165 kDa) chain was slightly different between the two cell lines; more α3 chain being processed in PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 than in PA-JEB/β4-EGFP cells. There was no evidence for extracellular processing of the γ2 chain (155 kDa). The band of 145 kDa corresponds to the β3 chain. Furthermore, the total content of laminin-5 in the matrices deposited by PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 and PA-JEB/β4-EGFP cells was comparable.

In summary, both EGFP chimeras are able to induce the assembly of hemidesmosomes, but although this assembly by EGFP-β4 is entirely driven from within the cell (Nievers et al., 2000), that by β4-EGFP is also induced by an interaction of its extracellular domain with LN-5.

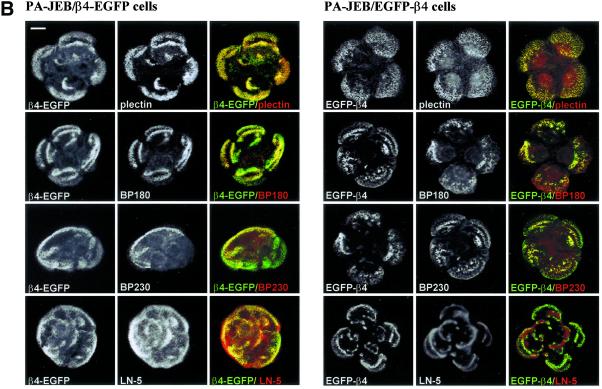

Dynamics of Hemidesmosome Formation

Time-lapse videomicroscopy was used to study the distribution of hemidesmosomes during the random movement of keratinocytes. When cultured in high Ca2+ medium, PA-JEB/β4-EGFP and PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 keratinocytes hardly migrate but move primarily in situ by continuously extending and retracting their membrane. Changes in the distribution pattern of hemidesmosomes are readily detected in these cells over a period of 3 h (Figure 3A). Existing hemidesmosomes in the central region of the cell disappear, and new hemidesmosomes are formed at the cell margins. Because of the extensions of the membrane of the cell in various directions, the distribution pattern of hemidesmosomes often has the appearance of a cauliflower. Cell retraction is accompanied by the formation of retraction fibers in which β4-EGFP, but not EGFP-β4, is present. The β4-EGFP–positive retraction fibers originate from hemidesmosomes, probably because β4-EGFP when associated with α6 cannot be released from its ligand without effort. In migrating cells, retraction fibers are formed at the rear of the cell and occasionally are left behind as “footprints” (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Dynamics of hemidesmosome formation. (A) Selected fluorescence micrographs taken from a time-lapse recording at time points 0, 90, and 195 min, depicting the change in distribution of β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 hemidesmosomes in PA-JEB/β4-EGFP and PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 cells, respectively. The left and two middle panels show an overlay of transmission optics and fluorescence. To improve the contrast of the composite, the green fluorescence of the EGFP chimeras is shown in blue. Right panel: a composite of the fluorescence images at time points 0 (in green) and 195 min (pseudocolored in red), with areas of overlap represented in yellow. Note that after 195 min, new β4-EGFP hemidesmosomes (top panel, red signal) have assembled at the cell borders, whereas preexisting hemidesmosomes (top panel, green signal) in the central part of the cell have disappeared. Bar, 15 μm. (B) “Footprints” of PA-JEB/β4-EGFP keratinocytes. PA-JEB/β4-EGFP ker-atinocytes were fixed and immunostained for LN-5 (red). Composite images were generated by superimposition of the green and red signals. Areas of overlap appear yellow in the images. Migrating β4-EGFP keratinocytes leave footprints containing ripped off β4-EGFP membrane fragments still attached to the underlying matrix. Bar, 10 μm. (C) Time-lapse images of PA-JEB/β4-EGFP demonstrating that hemidesmosomes convert into retraction fibers during cell movement. Left panels: fluorescent images; right panels: the corresponding transmission optics. Note that when the cell body moves forward, hemidesmosomes are gradually converted into retraction fibers (A–F). Some fusion of retraction fibers occurs and eventually the retraction fibers become smaller and are pulled back into the cell (arrows, D–G). The arrow in panel A points at the appearance of retraction fibers. The arrow in panel J points to membrane extensions of the neighboring cell. Note that the disassembly of hemidesmosomes and their conversion into retraction fibers lead to withdrawing of the cell in the left corner, thereby allowing the cell below it to migrate into the cleared space (F–J).

Time-lapse videomicroscopy also revealed that as the cell further retracts its membrane the β4-EGFP retraction fibers become thinner and longer, and new ones emerge (Figure 3C, A–F). Fusion of retraction fibers is also observed (Figure 3C, arrow, panels E and F). Eventually, the fibers become smaller and are pulled back inside the cell. In panels F–J, it can be seen that the empty space left behind by the migrating cell is quickly occupied by another cell that extends its membrane from the leading edge. No β4-EGFP can be detected in these membrane extensions, which suggests that α6β4 is not an essential component of newly formed filopodia or lamellipodia. Together these results show that both β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 hemidesmosomes are assembled and redistributed in a short period of time. Only β4 chimeras (β4-EGFP) that interact with LN-5 are retained in retraction fibers.

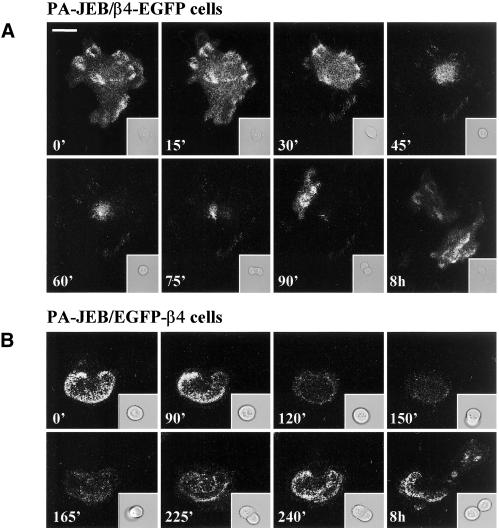

Retraction Fibers Mediate the Final Bond of PA-JEB/β4-EGFP Cells with LN-5 during Migration and Mitosis

Hemidesmosomes do not disassemble when keratinocytes divide (Baker et al., 1993). Nevertheless, during the mitotic process, cells have to undergo cellular rounding, which is accompanied by a complete reorganization of the cytoskeleton. To investigate whether the localization of hemidesmosomes changes during mitosis, we recorded the fluorescence of β4-EGFP– and EGFP-β4–containing hemidesmosomes during spontaneous cell divisions. Figure 4A shows a series of images of a dividing PA-JEB/β4-EGFP cell. The images were taken at 15-min intervals over a period of 90 min and after completion of cell division (+8 h). When mitosis begins, the cell starts to round up and to detach from the matrix. The hemidesmosomes located at the cell borders are converted into retraction fibers (Figure 4A, 30 min). When the rounding of the cell is completed, it is still attached to the LN-5 matrix via a network of β4-EGFP positive retraction fibers (45 min). These fibers keep the cell at its position during the mitotic process (60–75 min) and subsequently will facilitate the spreading of the daughter cells (Cramer and Mitchison, 1993; Mitchison and Cramer, 1996). After completion of cell division, the daughter cells spread on the LN-5 matrix that was already present beneath the dividing cell, and new hemidesmosomes are formed at exactly the same position at which the β4-EGFP retraction fibers arose from the matrix (Figure 4A, 8 h). Thus, as in migrating cells, in mitotic cells the β4-EGFP containing hemidesmosomes are converted into retraction fibers. The reverse reaction, the conversion of retraction fibers into β4-EGFP containing hemidesmosomes, also occurs and is most frequently seen after completion of cell division, when the rounded cells begin to spread.

Figure 4.

Hemidesmosomes of β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 keratinocytes disappear during mitosis. Time-lapse images of dividing PA-JEB/β4-EGFP (A) and PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 (B) cells. Shown are fluorescent images with the corresponding transmission optics in the right corner of every panel. Note that β4-EGFP hemidesmosomes convert into retraction fibers, whereas EGFP-β4 hemidesmosomes do not but are reduced to small structures that no longer appear as hemidesmosomes. Retraction fibers not only form at the rear end during cell contraction, but also promote respreading of cells after mitosis, consequently the hemidesmosomal pattern before and after mitosis is similar.

EGFP-β4 hemidesmosomes do not convert into retraction fibers but are redistributed during mitosis (Figure 4B). Their number at the sites where the cell is attached to the matrix decreases during the process of mitosis. Finally, when the cell is rounded, a spot-like staining pattern represents the only structure that remains of the EGFP-β4 hemidesmosomes. After cell division, the EGFP-β4 hemidesmosomes reappear in the daughter cells that start to spread. The hemidesmosomal pattern that is finally formed after spreading of the daughter cells is the same as before the onset of mitosis (Figure 4B, 8 h). The transmission images further demonstrate that spreading of the PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 cells is associated with extension of the membranes and the formation of bleb-like structures (Figure 4B, 225–240 min). Together, these data demonstrate that during mitosis β4-EGFP hemidesmosomes are converted into retraction fibers, whereas those containing EGFP-β4 are reduced to small structures that no longer resemble hemidesmosomes. After cell division is completed hemidesmosomes are reassembled.

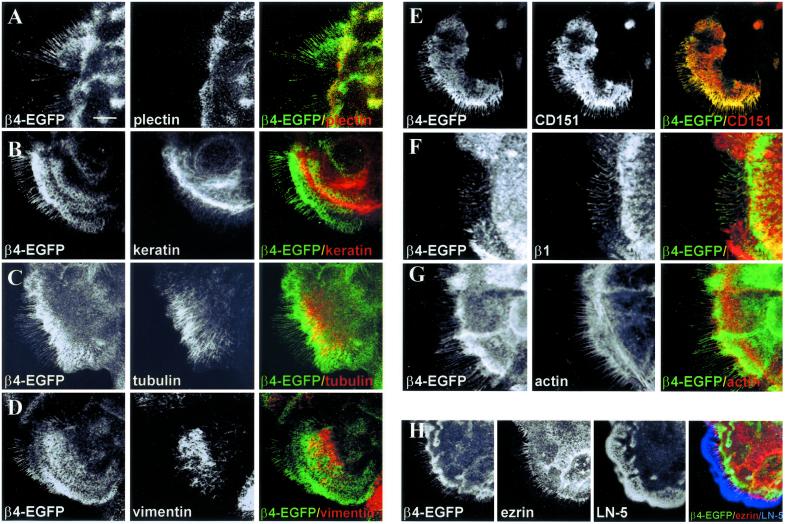

β4-EGFP Is Not Associated with the Intermediate Filament System in Retraction Fibers

Because retraction fibers that contain β4-EGFP appeared to originate from hemidesmosomes, we investigated which other components of hemidesmosomes are present in them. No BP180, BP230, or plectin could be detected in β4-EGFP-positive retraction fibers. Actually plectin, that mediates the linkage of β4 to the intermediate filament system, is already dissociated from α6β4 before the retraction fibers become visible (Figure 5A). This suggests that the integrin must be detached from the intermediate filament system before retraction fibers can be formed. Consistent with the fact that plectin is not present in retraction fibers, we could not detect the filament proteins, keratin or vimentin, or tubulin in these fibers either (Figure 5, B, C and D). On the other hand, the tetraspanin CD151 is colocalized with β4-EGFP along the retraction fibers and thus is the only other component that is present together with α6β4 in both hemidesmosomes and retraction fibers (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Components of retraction fibers. PA-JEB/β4-EGFP were fixed and incubated with mAb 121 against plectin (A) or with mAb KL-1 against keratin (B), a mixture of mAbs B-5-1-2 and 2-28-33 against mouse α and β tubulins (C), mAb RV202 against vimentin (D), mAb P48 against CD151 (E), mAb K20 against β1 (F), phalloidin Alexa 568 to stain actin filaments (G), mAb 3C12 against ezrin (H) and rabbit polyclonal anti–LN-5 antibodies (H). Texas-red– and Cy-5–conjugated secondary antibodies against mouse and rabbit IgG were used to detect bound antibodies. Composite images were generated by superimposition of the green and red signals, with areas of overlap represented in yellow. Where three colors were used (H), composite images were also generated by superimposition of the red, green, and Cy-5 signals, with areas of overlap represented in white. Because β4-EGFP and keratin did not appear in the same confocal plane, (B) is presented as a maximum projection of XYZ stacks. β1, actin, and ezrin, are not part of hemidesmosomes, but appear at the base of retraction fibers, and although present in the same structure are not colocalized with β4-EGFP (F–H). The intermediate filament proteins, keratin and vimentin, and tubulin stain throughout the body of the cell and are not part of hemidesmosomes (B–D). The keratinocyte remains still attached to its LN-5 matrix by retraction fibers (H). The hemidesmosomal components β4-EGFP and CD151 are colocalized in hemidesmosomes and throughout the retraction fibers (E). Plectin is associated with β4-EGFP in hemidesmosomes but is dissociated during the conversion of these structures into retraction fibers (A). Bar, 10 μm.

The β1 integrins are not colocalized with β4 in hemidesmosomes but are present in the focal contacts surrounding them (Schaapveld et al., 1998). Because the retraction fibers of migrating fibroblasts are composed of actin and β1 (Chen, 1981), we investigated whether these components are also present in the retraction fibers of PA-JEB/β4-EGFP cells. As shown in Figure 5, β1 is detected in retraction fibers, but it is not colocalized with β4-EGFP (Figure 5F). As expected, F-actin is also present in retraction fibers, and it was found to be more prominently present at their base (Figure 5G). No filamin, spectrin, talin, vinculin, or zyxin could be demonstrated in retraction fibers, which would imply that the β1 integrins are not connected to the actin cytoskeleton. However, ezrin, a protein that connects the cortical actin filaments with the plasma membrane, was detected in retraction fibers and, like F-actin, is more prominently localized at their base (Figure 5H). Ezrin is not present in hemidesmosomes. The β4-EGFP and ezrin-positive fibers are bound to LN-5 left behind after the cells have moved (unpublished data), confirming that they are in fact retraction fibers. Taken together these results suggest that α6β4 and β1 integrins present in retraction fibers are not associated with the cellular cytoskeleton.

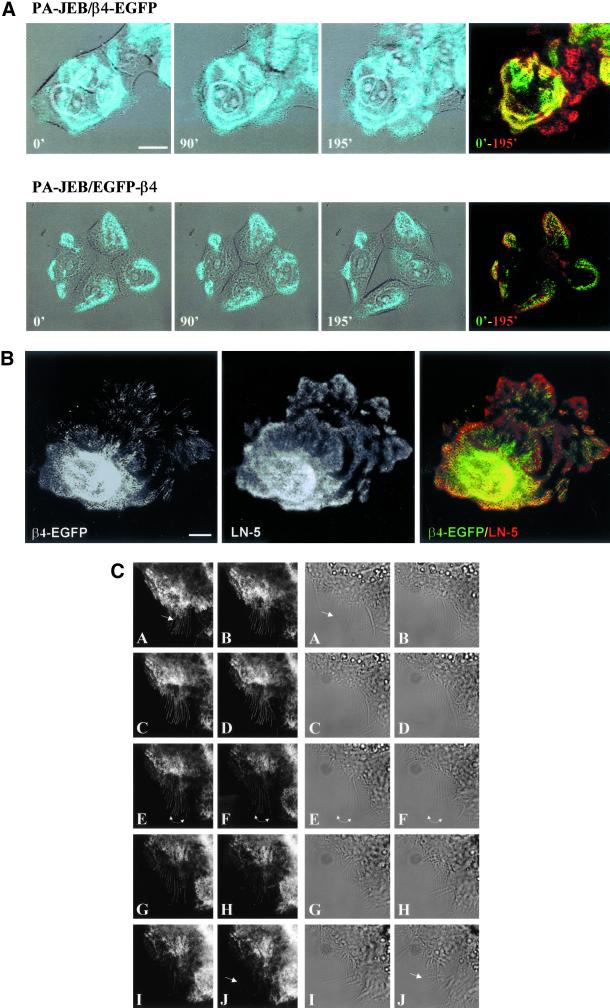

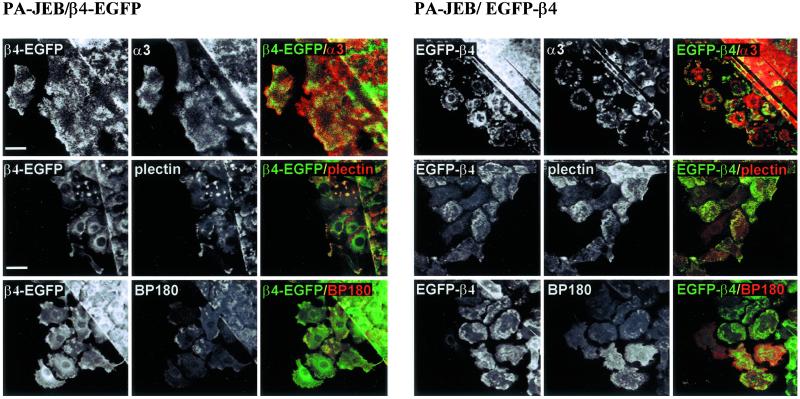

Stabilization of Membrane Extensions by β4-EGFP Is Not Required for Cell Migration

In several reports it has been shown that α6β4 associates with actin and is localized at the leading edge of invading carcinoma cells, where it is assumed to contribute to migration by stabilizing filopodia and lamellipodia (Rabinovitz et al., 1997; O'Connor et al., 1998; Goldfinger et al., 1999; Decline and Rousselle, 2001). We, therefore, studied the localization of α6β4 in PA-JEB/β4-EGFP keratinocytes migrating into a wound bed. In the wound area the migrating cells were of two types. One type contained large lamellipodia with β4-EGFP evenly distributed over the cell (Figure 6), whereas in the other type β4-EGFP appeared at the leading edge. These cell types most likely represent different phases in the migration of the cell, the first type representing a cell that is actually migrating, whereas the migration of the cells with β4 containing adhesion sites at their base has slowed down or perhaps even completely stopped. Although in the more stationary cells both α3β1 and β4-EGFP are present at the leading edge, they are clearly not colocalized, α3β1 being closer to the leading edge than β4-EGFP. Similar results were obtained with PA-JEB cells expressing EGFP-β4. To investigate whether the hemidesmosomal structures formed during migration are type I or type II hemidesmosomes, PA-JEB/β4-EGFP and PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 keratinocytes crossing the wound bed were incubated with antibodies against plectin or BP180. As shown in Figure 6, although plectin was always found together with the β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 clusters at the leading edge of the keratinocytes, BP180 was only occasionally colocalized with them. Thus, PA-JEB/β4-EGFP and PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 keratinocytes form both type I and type II hemidesmosomes during migration.

Figure 6.

During migration in a wound bed PA-JEB/β4-EGFP and PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 form type I or type II hemidesmosomes. Localization by immunofluorescence of the hemidesmosomal components β4, plectin, and BP180 in PA-JEB/β4-EGFP or PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 keratinocytes crossing the wounded area after 48 h. Note the different cell types present. Fan-shaped cells with β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 equally distributed over the cells (resulting in PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 with hardly visible green fluorescence) most likely represent truly migrating cells. The other cells likely just stopped migrating and both β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 appear at the leading edge of the cell, where α3β1 is also present. Plectin is always colocalized with β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 at the leading edge, whereas BP180 is occasionally present. Thus both type I and type II hemidesmosomes are formed by keratinocytes migrating into a wound bed. Bar, 20 μm, except for (A), where it indicates 10 μm.

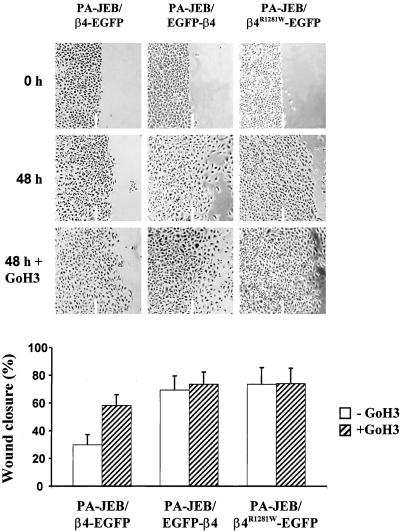

The Integrin α6β4 Slows Down Migration of Keratinocytes in Response to Wounding

The finding that α6β4 induces the formation of hemidesmosome-like structures during migration of PA-JEB/β4-EGFP keratinocytes prompted us to further investigate the role of this integrin in cell migration using in vitro wound healing assays. PA-JEB/β4-EGFP and PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 keratinocytes were grown to confluence after which a scratch wound was introduced in the monolayer. Phase contrast micrographs taken at 48 h demonstrated that the migration of PA-JEB/β4-EGFP keratinocytes is slower than that of PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 keratinocytes, implicating an inhibitory effect of β4 on cell migration when it can bind to its ligand LN-5 (Figure 7). Indeed, the mAb GoH3 known to block the adhesion of α6β4 to LN-5 enhances migration of PA-JEB/β4-EGFP cells. Furthermore, when the interaction of β4-EGFP with LN-5 is inhibited by the mAb GoH3, the β4-EGFP hemidesmosomes adopted the appearance of EGFP-β4 hemidesmosomes (see characteristic patterns of β4-EGFP- and EGFP-β4-hemidesmosomes in Figure 2A), the clusters of hemidesmosomes were more clearly stained and defined, and there was no β4-EGFP in retraction fibers.

Figure 7.

Cell motility is inhibited by binding of α6β4 to plectin. PA-JEB/β4-EGFP, PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 and PA-JEB/β4R1281W-EGFP keratinocytes were grown to confluence on glass coverslips and treated for 2 h before wounding with 10 μg/ml mitomycin C to prevent proliferation of cells. The monolayers were then wounded and cell migration was determined after 48 h in the presence or absence of α6 blocking antibodies. Expression of the LN-5 binding β4-EGFP chimera in PA-JEB cells slows down cell migration. Blocking of the α6β4-LN-5 interaction by using the α6 blocking antibody GoH3 at a concentration of 25 μg/ml, enhanced migration of PA-JEB/β4-EGFP keratinocytes and made it comparable to that of PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 cells. There was no effect of α6β4 on migration when a mutant of β4 (β4R1281W), incapable of interacting with the cytoskeleton was used. Blocking of the α6β4-LN5 interaction did not promote migration. In the bar graph, results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Because α6β4 can interact with plectin and thereby become connected to the cytoskeleton, it is possible that the inhibition of migration by α6β4 is not due to the increased adhesion to LN-5 but rather to the stabilization of this adhesion as a result of the interaction of α6β4 with the cytoskeleton. To investigate this, we generated an EGFP version of a mutant β4 subunit, β4R1281W, that can bind to LN-5 but not to plectin (Geerts et al., 1999; Koster et al., 2001). We found that when this mutant is stably expressed in β4-negative PA-JEB keratinocytes, migration was hardly affected. In fact, the PA-JEB/β4R1281W-EGFP keratinocytes move as fast as PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 keratinocytes (Figure 6). We conclude that the inhibition of migration by α6β4 is due to the stabilization of the bond of α6β4 and LN-5 through the interaction of β4 with plectin.

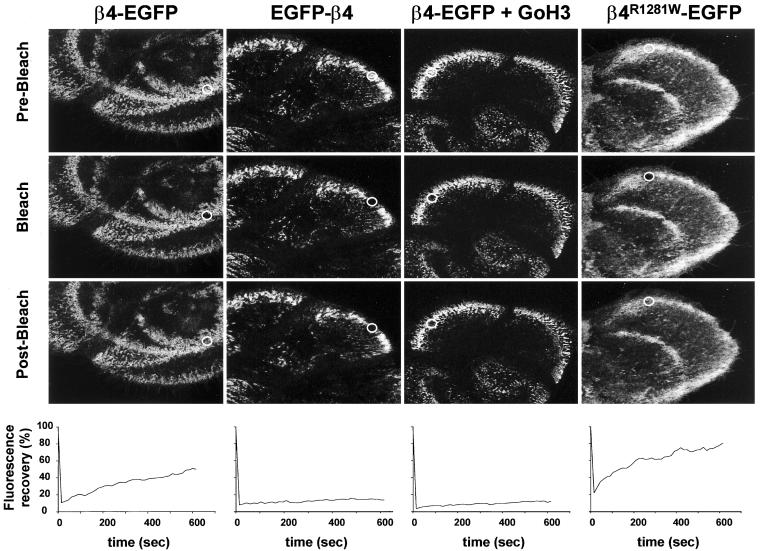

FRAP Analysis of EGFP-tagged Fusion Proteins in Live Keratinocytes

FRAP was used to determine the dynamics of β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 in hemidesmosomes of live keratinocytes. PA-JEB/β4-EGFP and PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 cells were examined by time-lapse two-photon excitation microscopy (Figure 8). After photobleaching, fluorescence of β4-EGFP had recovered for 32% (±2%) within the first 4 min and for 56% (±6%) after 10 min. The recovery of EGFP-β4 occurred much more slowly, i.e., 12% (±1%) after 10 min. There was no fast recovery in the first 4 min, and the rate of the EGFP-β4 recovery remained constant throughout time. Thus, in hemidesmosomes of live cells, EGFP-β4 is less dynamic than β4-EGFP. Because the β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 chimeras only differ in their capacity to bind the ligand LN-5, this suggests that interaction with ligand increases the dynamics of α6β4. To investigate whether indeed the dynamics of β4 are dependent on its interaction with LN-5, binding of β4-EGFP to LN-5 was blocked by adding the α6 blocking antibody GoH3 to PA-JEB/β4-EGFP keratinocytes, a treatment that results in a distribution of hemidesmosomes comparable with that in PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 (see above). When these cells were subjected to FRAP analysis, recovery of fluorescence occurred as slowly as that in the case of EGFP-β4. Thus, the bond between α6β4 and LN-5 is not stable and can be broken, which makes the integrin a dynamic protein. In PA-JEB/β4R1281W-EGFP cells, clusters of β4R1281W-EGFP can be observed. However, these clusters cannot be considered to be hemidesmosomes, because plectin, an essential component of hemidesmosomes, cannot bind to this β4 mutant. FRAP analysis of β4R1281W-EGFP was performed to investigate the contribution of the interaction of β4 with the cytoskeleton to the dynamics of β4. The recovery of fluorescence was faster with β4R1281W-EGFP than with β4-EGFP. Within the first 4 min, fluorescence recovers for 58% (±4%), and eventually the recovery reaches 77% (±5%) after 10 min. Diffusion coefficients for the different proteins were not calculated because the fluorescence of EGFP-β4 and β4-EGFP+GoH3 hardly recovered and because the fluorescence recovery curves for β4-EGFP and β4R1281W-EGFP do not fit with a single exponential (see MATERIALS AND METHODS). However, the observed differences between the different recovery curves are consistent and striking. Thus, the bond between α6β4 and LN-5 is less easily broken (i.e., less dynamic) when α6β4 is associated with cytoskeleton.

Figure 8.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) of EGFP chimeras is dependent on LN-5 binding. PA-JEB/EGFP-β4, PA-JEB/β4-EGFP, PA-JEB/β4R1281W-EGFP keratinocytes and PA-JEB/β4-EGFP cells that had been treated with the α6 blocking antibody GoH3 were photobleached for 1 s using 100% laser power at t = 0. Fluorescence recovery was subsequently monitored by acquiring images every 15 s for a period of 10 min. Top panels: fluorescence images of cells before bleaching, immediately after bleaching, and 10 min after bleaching. The bleached area is depicted by a white oval. Bottom panels: representative recovery curves of fluorescence in the bleached area. The fluorescence was related to the initial fluorescence (set at 100%) and corrected for loss of fluorescence due to bleaching and scanning procedure. The presented figures represent a typical experiment of which four that were performed with similar results. After photobleaching, fluorescence of β4-EGFP had recovered for 32% (±2%) within the first 4 min and for 56% (±6%) after 10 min. The recovery of EGFP-β4 occurred much more slowly, i.e., 12% (±1%) after 10 min, and was similar to the recovery of β4-EGFP incubated with mAb GoH3, 13% (±0.5%). The β4R1281W-EGFP shows the fastest recovery of fluorescence compared with β4-EGFP. Within the first 4 min the fluorescence recovers for 58% (±4%). Eventually, leading to a recovery of β4R1281W-EGFP fluorescence of 77% (±5%) after 10 min. Thus, the dynamics of the interaction of β4 with LN-5 is suppressed by the association of β4 with the cytoskeleton.

DISCUSSION

The integrin α6β4 is an essential component of hemidesmosomes and is necessary for tightly anchoring keratinocytes to the extracellular matrix (Jones et al., 1998; Borradori and Sonnenberg, 1999). When epithelial cells are induced to migrate in response to wounding, they lose their hemidesmosomes, probably to reduce their strong adhesion to the substratum (Riddelle et al., 1992; Gipson et al., 1993). In carcinoma cells, α6β4 contributes to migration and invasion by activation of PI-3 kinase signaling (Chao et al., 1996; Shaw et al., 1997). Thus α6β4 plays a dual and apparently paradoxical role because it is essential both to keep cells stationary and to promote migration.

In this study, we analyzed the dynamics of α6β4 in stationary and migrating keratinocytes by expressing a β4 subunit tagged with EGFP, in β4-deficient keratinocytes. Furthermore, the involvement of ligand binding in the dynamics of α6β4 was investigated by using an EGFP-β4 chimera that is unable to bind to LN-5. Time-lapse videomicroscopy demonstrated that in moving and dividing keratinocytes, β4-EGFP and EGFP-β4 hemidesmosome-like structures are assembled and redistributed within minutes. Unfortunately, we could not determine whether these hemidesmosomal structures are type I or type II hemidesmosomes, because the other hemidesmosomal components plectin, BP180, and BP230 could not be made visible during the time-lapse recordings.

During migration, the leading edge of lamellipodia and filopodia is the site where new adhesions are formed. Both in randomly moving cells and in cells that migrate into cleared areas after the monolayer has been wounded, clustered β4-EGFP appears at the leading edge of the keratinocytes, as has also been shown by others (Goldfinger et al., 1999). The LN-5 binding integrin α3β1 was also concentrated at these sites and was even closer to the leading edge of the cell than β4-EGFP. Several reports have suggested a role of α6β4 in stabilizing newly formed filopodia and lamellipodia in order to facilitate migration (Rabinovitz and Mercurio, 1997; O'Connor et al., 1998). However, we show that EGFP-β4, which cannot interact with LN-5, also becomes concentrated at these sites. This suggests that β4 is involved in a different process, i.e., the formation of new hemidesmosomes. This assumption is supported by the colocalization of plectin and, in some cells of BP180 and BP230, with EGFP-β4 at these sites. In contrast, in highly motile cells displaying a characteristic fan-shaped morphology, neither β4-EGFP nor EGFP-β4 are clustered but are diffusely distributed throughout the cell. The mechanism responsible for the localization of EGFP-β4 at the leading edge is not known, but we assume that it is targeted by a direct or indirect association with α3β1. A role of the latter integrin in hemidesmosome formation has previously been suggested (Nievers et al., 1998, 2000; Sterk et al., 2000) and is supported by the strong reduction in the number of hemidesmosomes in mice that do not express β1 in the skin (Brakebusch et al., 2000; Raghavan et al., 2000).

Cell migration not only depends on the formation of cell-matrix adhesion by the moving cell, but also on breaking existing adhesions at the rear end of the cell. (Regen and Horwitz, 1992; Palecek et al., 1998). If these adhesions are strong, they will be less easily broken, which will result in the appearance of retraction fibers, causing migration to be slowed down. In PA-JEB/β4-EGFP keratinocytes many retraction fibers can be observed that originate from hemidesmosomes. These retraction fibers contain β4-EGFP, but no plectin, which suggests that in them the linkage of β4 with the cytoskeleton is fractured. Indeed, the intermediate filament proteins keratin and vimentin, to which plectin can bind, are not present in these retraction fibers. Incidentally, some of the β4 is ripped from the membrane and remains attached to the LN-5 matrix, leaving “footprints” of a migrating cell.

The detachment of plectin from β4 during the transition of hemidesmosomes into retraction fibers may be due to either mechanical stress or signaling events. Several studies have shown that phosphorylation of the β4 subunit by protein kinase C is associated with a redistribution of α6β4 from the hemidesmosome to the cytosol (Alt et al., 2001) and/or to F-actin–rich cell protrusions (Rabinovitz et al., 1999). Furthermore, the link between β4 and plectin might be cleaved by proteases such as the Ca2+-dependent protease calpain. This stimulates rear end release of CHO cells (Palecek et al., 1998) by cleavage of cytoskeletal linkages. In fact, calpain cleavage sites are present in the cytoplasmic domain of the β4 subunit (Giancotti et al., 1992). The reverse reaction, the reassociation of plectin with α6β4 occurs when retraction fibers convert into hemidesmosomes, which occurs prominently after mitosis (see Figure 4A).

Our study clearly shows that the introduction of β4-EGFP into a cell that lacks β4 slows down the migration of that cell. Previous work has shown that the proteolytic processing of the α3 chain of LN-5 by plasmin produces an LN-5 molecule that induces the assembly of hemidesmosomes and impedes cell migration (Goldfinger et al., 1998). On the contrary, proteolytic processing of the γ2 chain of LN-5 has been associated with the induction of cell migration (Giannelli et al., 1997). Although the relative amounts of processed α3 chain in the matrices produced by PA-JEB/β4-EGFP and PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 cells were slightly different, it is unlikely that this accounts for the observed differences in their migration. In fact, the migration of PA-JEB/β4-EGFP cells that produce the most unprocessed α3 is the slowest. Extracellular processing of the γ2 chain of LN-5 was not observed, and furthermore there was no obvious difference in the amount of LN-5 deposited by the two cell lines into the matrix. Thus, the difference in migration of PA-JEB/β4-EGFP and PA-JEB/EGFP-β4 cells cannot be due to differences in the proteolytic state or the amount of LN-5 molecules produced by them.

It is possible that the increased adhesion of cells to LN-5, due to the expression of β4-EGFP, by itself might already slow down migration. However, studies with a mutant β4 subunit (β4R1281W-EGFP) that cannot interact with plectin and therefore also not with the cytoskeleton (Geerts et al., 1999; Koster et al., 2001) showed that it is in fact the stabilization and not the magnitude of the adhesion to LN-5 that causes this effect. Plectin, which is a dimeric protein but also has been shown to form tetramers (Wiche, 1998), might stabilize the adhesion of α6β4 to LN-5 by linking two or more α6β4 molecules together. However, for this linking to occur, the α6β4 molecules must be close together. We have shown previously that when keratinocytes are seeded on a subconfluent LN-5 matrix, hemidesmosomes are distributed in a pattern that mirrors the pattern of LN-5 underneath the cell (Nievers et al., 2000), which implies that β4 preferentially interacts with LN-5, rather than with plectin. Thus, it is likely the density of LN-5 molecules underneath the cell that ultimately determines whether the interaction of α6β4 with LN-5 will be stabilized. Accordingly, when LN-5 is not concentrated into patches but is distributed diffusely over a surface, α6β4 will not be clustered. In that case, an interaction of α6β4 with plectin will not stabilize the adhesion of α6β4 to LN-5, and migration will not be slowed down. Indeed, we recently found that in β4-deficient PA-JEB cells transfected with β4, the α6β4 integrin accelerates migration on surfaces with homogenously distributed LN-5 (G. Smits and A. Sonnenberg, unpublished observations).

Hemidesmosome-like structures that are formed by β4-EGFP on the patches of LN-5, deposited by the cells themselves, appeared to be less well clustered than the ones that are formed by EGFP-β4. This may indicate that in these hemidesmosome-like structures, not all of the bindings between α6β4 and LN-5 are stabilized by interactions of β4 with plectin. Consistent with this notion, FRAP analysis showed that the recovery of fluorescence of β4-EGFP was faster than that of EGFP-β4, or of β4-EGFP of which the binding to LN-5 was prevented by the mAb GoH3. In fact, hardly any recovery of fluorescence of EGFP-β4 or of β4-EGFP/GoH3 could be detected over a period of 10 min. On the other hand, the mutant β4 subunit (β4R1281W-EGFP) that cannot bind to plectin displayed the fastest recovery of fluorescence. Thus, the binding dynamics of α6β4 interaction with LN-5 on the one hand and with plectin on the other hand influence each other in a reciprocal manner.

Why on the LN-5 patches not all of the interactions between α6β4 and LN-5 are stabilized by plectin is not clear. It is possible that the density of the LN-5 molecules in the patches is too low and that therefore not all of the α6β4 molecule are close enough to each other for their interaction with LN-5 to be stabilized by plectin. Alternatively, not all the LN-5 molecules in the matrices may be optimally presented. This might also explain why in tissue culture, hemidesmosomes almost never reach the level of maturation of true hemidesmosomes in the skin, i.e., with discernible inner and outer electron-dense plaques. In vivo, the presentation and the amount of LN-5 that is present under hemidesmosomes may not be a limiting factor and clustering and binding of α6β4 to the cytoskeleton might therefore be more extensive, allowing the formation of well-defined hemidesmosomes. Indeed, it has been shown that LN-5 is much more concentrated under hemidesmosomess than in regions where no hemidesmosomes are present (Rousselle et al., 1991).

Altogether our results suggest that the density of LN-5 underneath the cell ultimately determines to what extent the binding of α6β4 to LN-5 will become stabilized by interaction of β4 with plectin and whether α6β4 will inhibit migration or not.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Jalink for help and suggestions with the FRAP experiments, L. Oomen and L. Brocks for excellent assistance with the confocal microscope, A. Pfauth and E. Noteboom for their assistance with the FACS analysis of cells, and N. Ong for photographic work. We acknowledge Drs. C.P.E. Engelfriet, E. Danen, E. Roos, and G. Smits for critical reading of the manuscript. We are grateful to many of our colleagues for providing us with antibody reagents. This work was supported by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (NKI-99–2039).

Abbreviations used:

- LN-5

laminin-5

- PA-JEB

pyloric atresia associated with junctional epidermolysis bullosa

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- BP

bullous pemhigoid antigen

- IL2R

interleukin-2 receptor

- FRAP

fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

Footnotes

Online version of this article contains video material. Online version is available at www.molbiolcell.org.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.02–01–0601. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.02–01–0601.

REFERENCES

- Alt A, et al. Protein kinase Cδ-mediated phosphorylation of α6β4 is associated with reduced integrin localization to the hemidesmosome and decreased keratinocyte attachment. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4591–4598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashman LK, Fitter S, Sincock PM, Nguyen LY, Cambareri AC. CD151 (PETA-3) workshop summary report. In: Kishimoto T, et al., editors. Leukocyte Typing VI. White Cell Differentiation Antigens. New York: Garland Publishing Inc.; 1997. pp. 681–683. [Google Scholar]

- Ballestrem C, Hinz B, Imhof BA, Wehrle-Haller B. Marching at the front and dragging behind: differential αvβ3-integrin turnover regulates focal adhesion behavior. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:1319–1332. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J, Garrod D. Epithelial cells retain junctions during mitosis. J Cell Sci. 1993;104:415–425. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.2.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borradori L, Sonnenberg A. Structure and function of hemidesmosomes: more than simple adhesion complexes. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;112:411–418. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakebusch C, et al. Skin and hair follicle integrity is crucially dependent on β1 integrin expression on keratinocytes. EMBO J. 2000;19:3990–4003. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao C, Lotz MM, Clarke AC, Mercurio AM. A function for the integrin α6β4 in the invasive properties of colorectal carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1996;15:4811–4819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W-T. Mechanism of retraction the trailing edge during fibroblast movement. J Cell Biol. 1981;90:187–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.90.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer L, Mitchison TJ. Moving and stationary actin filaments are involved in spreading of postmitotic PtK2 cells. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:833–843. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.4.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decline F, Rousselle P. Keratinocyte migration requires α2β1 integrin-mediated interaction with the laminin 5 γ2 chain. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:811–823. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontao L, Dirrig S, Owaribe K, Kedinger M, Launay JF. Polarized expression of HD1, relationship with the cytoskeleton in cultured human colonic carcinoma cells. Exp Cell Res. 1997;231:319–327. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.3465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambaletta D, Marchetti A, Benedetti L, Mercurio AM, Sacchi A, Falcioni R. Cooperative signaling between α6β4 integrin and ErbB-2 receptor is required to promote phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent invasion. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10604–10610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerts D, Fontao L, Nievers MG, Schaapveld RQJ, Purkis PE, Wheeler GN, Lane EB, Leigh IM, Sonnenberg A. Binding of integrin α6β4 to plectin prevent plectin association with F-actin but does not interfere with intermediate filament binding. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:417–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancotti FG, Stepp MA, Suzuki S, Engvall E, Ruoslahti E. Proteolytic processing of endogenous and recombinant β4 integrin subunit. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:951–959. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.4.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannelli G, Falk-Marzillier J, Schiraldi O, Stetler-Stevenson G, Quaranta V. Induction of cell migration by matrix metalloprotease-2 cleavage of laminin-5. Science. 1997;277:225–228. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gipson IK, Spurr-Michaud S, Tisdale A, Elwell J, Stepp MA. Redistribution of the hemidesmosome components α6β4 integrin and bullous pemphigoid antigens during epithelial wound healing. Exp Cell Res. 1993;207:86–98. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfinger LE, Stack MS, Jones JCR. Processing of laminin-5 and its functional consequences: role of plasmin and tissue-type plasminogen activator. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:255–265. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfinger LE, Hopkinson SB, deHart GW, Collawn S, Couchman JR, Jones JC. The α3 laminin subunit, α6β4 and α3β1 integrin coordinately regulate wound healing in cultured epithelial cells and in the skin. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2615–2629. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.16.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KJ, Jones JC. Desmosomes and hemidesmosomes, structure and function of molecular components. FASEB J. 1996;10:871–881. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.8.8666164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, et al. Further analysis of epitopes for human monoclonal anti-basement membrane zone antibodies produced by stable human hybridoma cell lines constructed with Epstein-Barr virus transformants. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:310–315. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12469916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hieda Y, Nishizawa Y, Uematsu J, Owaribe K. Identification of a new hemidesmosomal protein, HD1: a major, high molecular mass component of isolated hemidesmosomes. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:1497–1506. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.6.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintermann E, Bilban M, Sharabi A, Quaranta V. Inhibitory role of α6β4-associated erbB-2 and phosphoinositide 3-kinase in keratinocyte haptotactic migration dependent on α3β1 integrin. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:465–478. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JC, Hopkinson SB, Goldfinger LE. Structure and assembly of hemidesmosomes. Bioessays. 1998;20:488–494. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199806)20:6<488::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella TM, Nolan GP. Episomal vectors rapidly and stably produce high-titer recombinant retrovirus. Human Gen Ther. 1996;7:1405–1413. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.12-1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster J, Kuikman I, Kreft M, Sonnenberg A. Two different mutations in the cytoplasmic domain of the integrin β4 subunit in nonlethal forms of epidermolysis bullosa prevent interaction of β4 with plectin. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1405–1411. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukaitis CM, Webb DJ, Donais K, Horwitz AF. Differential dynamics of α5 integrin, paxillin, and α-actinin during formation and disassembly of adhesions in migrating cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1427–1440. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.7.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longin A, Souchier C, Ffrench M, Bryon PA. Comparison of anti-fading agents used in fluorescence microscopy, image analysis and laser confocal microscopy study. J Histochem Cytochem. 1993;41:1833–1840. doi: 10.1177/41.12.8245431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainiero F, Pepe A, Yeon M, Ren Y, Giancotti FG. The intracellular functions of α6β4 integrin are regulated by EGF. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:241–253. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.1.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinkovich MP, Lunstrum GP, Burgeson RE. The anchoring filament protein kalinin is synthesized and secreted as a high molecular weight precursor. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:17900–17906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti A, Kedeshian PK, Dans M, Curatola AM, Gagnoux-Palacios L, Giancotti FG. EGF-R signaling through Fyn kinase disrupts the function of integrin α6β4 at hemidesmosomes, role in epithelial cell migration and carcinoma invasion. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:447–458. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P. Wound healing—aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science. 1997;276:75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchison TJ, Cramer LP. Actin-based cell motility and cell locomotion. Cell. 1996;84:371–379. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen BP, Gil SG, Carter WG. Deposition of laminin 5 by keratinocytes regulates integrin adhesion and signaling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31896–31907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niessen CM, van der Raaij-Helmer LMH, Hulsman EHM, van der Neut R, Jonkman MF, Sonnenberg A. Deficiency of the β4 subunit in junctional epidermolysis bullosa with pyloric atresia: consequences for hemidesmosome formation and adhesion properties. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1695–1706. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.7.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nievers MG, Schaapveld RQJ, Oomen LCJM, Fontao L, Geerts D, Sonnenberg A. Ligand-independent role of the β4 integrin subunit in the formation of hemidesmosomes. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:1659–1672. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.12.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nievers MG, Schaapveld RQJ, Sonnenberg A. Biology and function of hemidesmosomes. Matrix Biol. 1999;18:5–17. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(98)00003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nievers MG, Kuikman I, Geerts D, Leigh IM, Sonnenberg A. Formation of hemidesmosome-like structures in the absence of ligand binding by the α6β4 integrin requires binding of HD1/plectin to the cytoplasmic domain of the β4 integrin subunit. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:963–973. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.6.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa Y, Uematsu J, Owaribe K. HD4, a 180 kDa bullous pemphigoid antigen is a major transmembraneglycoprotein of the hemidesmosome. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1993;113:493–501. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor KL, Shaw LM, Mercurio AM. Release of cAMP gating by the α6β4 integrin stimulates lamellae formation and the chemotactic migration of invasive carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1749–1760. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orian-Rousseau V, Aberdam D, Fontao L, Chevalier L, Meneguzzi G, Kedinger M, Simon-Assmann O. Developmental expression of laminin-5 and HD1 in the intestine: epithelial to mesenchymal shift for the laminin γ2 chain subunit deposition. Dev Dyn. 1996;206:12–23. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199605)206:1<12::AID-AJA2>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palecek SP, Huttenlocher A, Horwitz AF, Lauffenburger DA. Physical and biochemical regulation of integrin release during rear detachment of migrating cells. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:929–940. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.7.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovitz I, Mercurio AM. The integrin α6β4 functions in carcinoma cell migration on laminin-1 by mediating the formation and stabilization of actin-containing motility structures. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1873–1884. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.7.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovitz I, Toker A, Mercurio AM. Protein kinase C-dependent mobilization of the α6β4 integrin from hemidesmosomes and its association with actin-rich cell protrusions drive the chemotactic migration of carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:1147–1159. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.5.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan S, Bauer C, Mundschau G, Li Q, Fuchs E. Conditional ablation of β1 integrin in skin: severe defects in epidermal proliferation, basement membrane formation, and hair follicle invagination. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1149–1160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regen CM, Horwitz AF. Dynamics of β1 integrin-mediated adhesive contacts in motile fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1347–1359. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.5.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddelle KS, Hopkinson SB, Jones JC. Hemidesmosomes in the epithelial cell line 804G, their fate during wound closure, mitosis and drug induced reorganization of the cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 1992;103:475–490. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.2.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousselle P, Lunstrum GP, Keene DR, Burgeson RE. Kalinin: an epithelium-specific basement membrane adhesion molecule that is a component of anchoring filaments. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:567–576. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.3.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaapveld RQJ, et al. Hemidesmosome formation is initiated by the β4 integrin subunit, requires complex formation of Symbol“ § 124 and H.D1/plectin, and involves a direct interaction between Symbol” § 124 and the bullous pemphigoid antigen 180. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:271–284. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.1.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw LM, Rabinovitz I, Wang HH, Toker A, Mercurio AM. Activation of phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase by the α6β4 integrin promotes carcinoma invasion. Cell. 1997;91:949–960. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw LM. Identification of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) and IRS-2 as signaling intermediates in the α6β4 integrin-dependent activation of phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase and promotion of invasion. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5082–5093. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.5082-5093.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smilenov LB, Mikhailov A, Pelham RJ, Marcantonio EE, Gundersen GG. Focal adhesion motility revealed in stationary fibroblasts. Science. 1999;286:1172–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg A, Janssen H, Hogervorst F, Calafat J, Hilgers J. A complex of platelet glycoproteins Ic and IIa identified by a rat monoclonal antibody. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10376–10383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterk LM, Geuijen CA, Oomen LC, Calafat J, Janssen H, Sonnenberg A. The tetraspan molecule CD151, a novel constituent of hemidesmosomes, associates with the integrin α6β4 and may regulate the spatial organization of hemidesmosomes. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:969–982. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.4.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusolino L, Bertotti A, Comoglio PM. A signaling adaptor function for α6β4 integrin in the control of HGF-dependent invasive growth. Cell. 2001;107:643–654. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00567-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uematsu J, Nishizawa Y, Sonnenberg A, Owaribe K. Demonstration of type II hemidesmosomes in a mammary gland epithelial cell line, BMGE-H. J Biochem. 1994;115:469–476. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen FN, Kain HET, van der Kammen RA, Michiels F, Kranenburg OW, Collard JG. The guanine nucleotide exchange factor Tiam1 affects neuronal morphology; opposing roles for the small GTPases Rac and Rho. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:797–807. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.3.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiche G. Role of plectin in cytoskeleton organization and dynamics. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2477–2486. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.17.2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.