Abstract

Mutations in the budding yeast myosins-I (MYO3 and MYO5) cause defects in the actin cytoskeleton and in the endocytic uptake. Robust evidence also indicates that these proteins induce Arp2/3-dependent actin polymerization. Consistently, we have recently demonstrated, using fluorescence microscopy, that Myo5p is able to induce cytosol-dependent actin polymerization on the surface of Sepharose beads. Strikingly, we now observed that, at short incubation times, Myo5p induced the formation of actin foci that resembled the yeast cortical actin patches, a plasma membrane-associated structure that might be involved in the endocytic uptake. Analysis of the machinery required for the formation of the Myo5p-induced actin patches in vitro demonstrated that the Arp2/3 complex was necessary but not sufficient in the assay. In addition, we found that cofilin was directly involved in the process. Strikingly though, the cofilin requirement seemed to be independent of its ability to disassemble actin filaments and profilin, a protein that closely cooperates with cofilin to maintain a rapid actin filament turnover, was not needed in the assay. In agreement with these observations, we found that like the Arp2/3 complex and the myosins-I, cofilin was essential for the endocytic uptake in vivo, whereas profilin was dispensable.

INTRODUCTION

Myosins-I are ubiquitous actin-dependent motors that bear a basic tail that binds acidic phospholipids (Pollard et al., 1991; Mooseker and Cheney, 1995). Subcellular localization and genetic analysis of their function point to their role in membrane traffic, particularly within the endocytic pathway (Novak et al., 1995; Durrbach et al., 1996, 2000; Geli and Riezman, 1996; Jung et al., 1996; Yamashita and May, 1998; Huber et al., 2000; Neuhaus and Soldati, 2000). MYO3 and MYO5 encode the Saccharomyces cerevisiae myosins-I, which are required for endocytic uptake in vivo (Geli and Riezman, 1996; Goodson et al., 1996). In addition, the yeast myosins-I are needed to generate cortical actin patches in semipermeabilized cells (Lechler et al., 2000). The yeast cortical actin patches are actin-coated plasma membrane invaginations (Mulholland et al., 1994) that might participate in the endocytic uptake (Pruyne and Bretscher, 2000). A major insight was recently made that might help elucidating how Myo3p and Myo5p participate in the generation of primary endocytic vesicles and/or cortical actin patches. Robust data indicate that the fungal and protozoal myosins-I contribute to activate Arp2/3-dependent actin polymerization at the plasma membrane (Evangelista et al., 2000; Geli et al., 2000; Lechler et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2000; Jung et al., 2001). Beside the motor head and the basic membrane-binding domain (tail homology domain 1 [TH1]), most myosins-I include a C-terminal fragment with a QPA-rich (TH2), and an SH3 (TH3) domain (Pollard et al., 1991; Mooseker and Cheney, 1995). In addition, the fungal myosins-I bear an acidic peptide (Evangelista et al., 2000; Lechler et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2000) that is also present in other activators of the Arp2/3 complex such as Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein (WASP; Machesky et al., 1999; Rohatgi et al., 1999; Winter et al., 1999b; Yarar et al., 1999). Genetic analysis demonstrates that myosins-I are functionally redundant with the WASP counterparts in fungi (S. cerevisiae Las17p and S. pombi Wsp1p; Evangelista et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2000) and both the Dictyostelium and fungal myosins-I physically interact with the Arp2/3 complex (Evangelista et al., 2000; Lechler et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2000; Jung et al., 2001). In addition, the C-terminal fragment of the S. pombe myosin-I weakly activates the nucleating activity of purified Arp2/3 complex (Lee et al., 2000). Consistently, we demonstrated, using fluorescence microscopy, that a glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion protein bearing the TH2, the SH3, and the acidic domains of Myo5p (residues 984-1219, GST-Myo5-Cp) induces cytosol-dependent actin polymerization on glutathione-Sepharose beads (Geli et al., 2000). Strikingly, observation of the myosin-coated beads at short incubation times revealed that the rhodamine-actin signal appeared as distinct foci that contained components of the yeast cortical actin patches. Analysis of the cellular machinery required for the formation of these structures demonstrated that the Arp2/3 complex was required but not sufficient in the process. In addition, we found that cofilin was directly involved in the generation of the Myo5p-induced actin foci. Strikingly though, the cofilin requirement seemed to be independent of its ability to disassemble filamentous actin and profilin, a protein that closely cooperates with cofilin to maintain a rapid actin filament turnover (Lappalainen and Drubin, 1997; Wolven et al., 2000), was not necessary in the process. Interestingly and consistent with our results in vitro, we found that the functions of cofilin and profilin could also be dissected in vivo. Cofilin, but not profilin, was found to be essential for the formation of endocytic vesicles at the plasma membrane, a process that might be functionally related to the generation of cortical actin patches and that requires the myosins-I and the Arp2/3 complex (Geli and Riezman, 1996; Moreau et al., 1997; Schaerer-Brodbeck and Riezman, 2000).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Genetic Techniques

Yeast strains used in this report are listed in Table 1. Unless otherwise mentioned, strains without plasmids were grown in complete yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) media, and strains with plasmids were selected on SDC synthetic D-glucose complete media (Dulic et al., 1991). Sporulation, tetrad dissection, and scoring of genetic markers were performed as described (Sherman et al., 1974). Transformation of yeast was accomplished by the lithium acetate method (Ito et al., 1983). The BY4741, BY4742, and Y22378 strains were purchased from Euroscarf (Institute for Microbiology, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany). SCMIG100 was generated from BY4741 by substituting the chromosomal copy of BAR1 with the URA3 marker. To generate SCMIG426, Y22378 was sporulated, dissected, and segregants were scored. A Matα pfy1Δ::KanMX4 lys2 segregant was crossed to SCMIG100. Diploids were selected on SDC medium without L-Lysine and subsequently on YPD containing 200 mg/l geneticin. Diploids were sporulated, tetrads were dissected, and segregants were scored for the appropriate markers. SCMIG134 was generated by crossing DDY1266 to RH2881. Diploids were selected on SDC medium without L-Lysine and without L-Leucine and sporulated, tetrads were dissected, and segregants were scored for the appropriated markers.

Table 1.

Yeast strains

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| RH2881 | Mata his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | H. Riezman |

| BY4741 | Mata his3 leu2 met15 ura3 | Euroscarf |

| BY4742 | Matα his3 leu2 lys2 ura3 | Euroscarf |

| Y22378 | Mata/α his3/his3 leu2/leu2 met15/MET15 LYS2/lys2 ura3/ura3 PFY1/pfy1Δ∷kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| SCMIG100 | Mata his3 leu2 met15 ura3 bar1Δ∷URA3 | This study |

| SCMIG426 | Mata his3 leu2 met15 Lys2 ura3 pfy1Δ∷kanMX4 bar1Δ∷URA3 | This study |

| DDY1252 | Matα his3 leu2 lys2 ura3 COF1∷LEU2 | D. Drubin |

| DDY1266 | Matα his3 leu2 lys2 ura3 cof1-22∷LEU2 | D. Drubin |

| SCMIG134 | Mata his3 leu2 ura3 trp1 lys2 cof1-22∷LEU2 bar1 | This study |

| SCMIG275 | Mata his3 leu2 lys2 trp1 ura3 bar1 myo5Δ∷TRP1 | H. Riezman |

| RH4149 | Matα Arp3-GFP-kanMx4 his3 leu2 ura3 trp1 | H. Riezman |

| RH4157 | Mata ura3 his3 leu2 lys2 arp3Δ∷HIS3 pDW20 (pCEN URA3 ARP3-5MYC6HIS) | H. Riezman |

| RH4165 | Mata arp2-2∷URA3 ade2 trp1 leu2 his ura3 bar1 | H. Riezman |

| RH4166 | Mata ade2 trp1 ura3 his3 leu2 arp3-62∷LEU2 bar1∷URA3 | H. Riezman |

| IDY223 | Mata his3 leu2 ura3 trp1 las17Δ∷LEU2 | A. Munn |

DNA Techniques and Plasmid Construction

Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. DNA manipulations were performed as described (Sambrook et al., 1989). Enzymes for molecular biology were obtained from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). Plasmids were purified with the Nucleobond plasmid purification kit. Transformation of Escherichia coli was performed by electroporation (Dower et al., 1988). Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed with a DNA polymerase with proof reading activity (Vent polymerase; New England Biolabs) and a TRIO-thermoblock (Biometra, Tampa, FL). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Interactiva (Ulm, Germany).

Table 2.

Plasmids

| Strain | Plasmid features | Insert | Domains | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pGSTMYO5-C | ori AMPR | GST-MYO5(aa984–1219) | TH2, SH3, A | M. I. Geli |

| pGSTMYO5-SA | ori AMPR | GST-MYO5(aa1085–1219) | SH3, A | M. I. Geli |

| pGSTLAS17-WA | ori AMPR | GST-LAS17(aa417–634) | WH2, A | This study |

| pGSTLAS17-PWA | ori AMPR | GST-LAS17(aa316–634) | PolyP, WH2, A | D. Drubin |

| p33MYO5-3HA | CEN4 URA3 ori AMPR | MYO5 + 3HA (C-terminal) | This study |

SDS-PAGE, Immunoblots, and Antibodies

SDS-PAGE was performed as described (Laemmli, 1970) using a Minigel system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). High and low range SDS-PAGE molecular weight standards (Bio-Rad Laboratories) were used for determination of molecular weight. Coomassie Brilliant Blue was used for detection of total protein. Protein concentration was determined with a Bio-Rad Protein assay. Immunoblots were performed as described (Geli and Riezman, 1998). The 9E10, 3F10, and C4 monoclonal antibodies (Roche Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) were used for detection of MYC and hemagglutinin (HA) epitopes, and actin, respectively. The polyclonal antibodies against yeast Abp1p, profilin (Pfy1p), and cofilin (Cof1p) were kindly provided by D. Drubin (University of California, Berkeley, CA). The polyclonal α-Ste2p antibody was kindly provided by H. Riezman (Biozentrum of the University of Basel, Switzerland). The polyclonal α-Tpm1p antibody was kindly provided by A. Bretscher (Cornell University, Ithaca, NY). Nitrocellulose membranes were stained with Ponceau red for detection of total protein. Fluorescent- and peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Dianova (Hamburg, Germany) and Sigma (St. Louis, MO), respectively.

Purification of Yeast Arp2/3 Complex, Recombinant Yeast Cof1p and GST Fusion Proteins

Yeast Arp2/3 complex was purified as described (Winter et al., 1999c) with some modifications. Briefly, a strain expressing a C-terminally 6His and myc-tagged Arp3p (Arp3-MHp) as the only source of Arp3p (RH4147) was lysed by grinding in liquid N2 in BUEA (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, and 0.2 mM ATP). Cells were thawed in the presence of protease inhibitors PI (0.5 mM phenyl methyl sulfoxide, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, and 1 μg/ml leupeptin), and the extract was clarified by centrifugation (2 h at 20,000g at 4°C). Proteins were fractionated on a Q Sepharose column (Q Sepharose fast flow; Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) using a salt gradient (100–500 mM KCl). Fractions bearing Arp3-MHp were pooled, and the Arp2/3 complex was precipitated with 40% ammonium sulfate. The precipitate was resuspended in BUI (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM imidazole) and was incubated with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Qiagen Gmbh, Hilden, Germany). The Arp2/3 complex was eluted with BUI 200 mM imidazole and was diluted one-tenth with XB (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.7, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 mM ATP). The Arp2/3 complex was bound to equimolar amounts of the GST-Myo5-Cp fusion protein on glutathione beads for 2 h at 4°C. A fraction of the beads was recovered, washed with XB 200 mM sucrose, and used for the visual actin polymerization assay. The remaining beads were eluted with XB 500 mM KCl to examine the purity of the Arp2/3 complex used in the assay. Purification of recombinant GST fusion proteins was performed as described (Geli et al., 2000). Cof1p was released from the beads by digestion with agarose-Thrombin (Thrombin clean cleavage kit; Sigma). For the actin polymerization assay, the GST fusion proteins were freshly purified to a final concentration of ∼2 mg of fusion protein per milliliter of 50% glutathione-Sepharose except for the GST-Las17-PWAp construct for which a final concentration of 0.1 mg of fusion protein per milliliter of 50% glutathione-Sepharose was used.

Yeast Extracts, Pull-Down Experiments, and Actin Pelleting Assay

Low-speed pelleted (LSP) yeast extracts for the actin polymerization assay were prepared as follows: cells grown to 1–2 × 107 cells/ml were harvested and glass bead-lysed in XB 50 mM sucrose (100 μl of buffer/g of wet yeast pellet) in the presence of PI. Samples were centrifuged at 2500g at 4°C and the supernatant was clarified at 20,000g for 10 min. High-speed pelleted (HSP) extracts were prepared by clarifying the LSP extracts by four times ultracentrifugation at 100,000g for 1 h. Protein and sucrose concentrations were adjusted to 20 μg/μl and 200 mM, respectively. Extracts were frozen in liquid N2 and were stored at −80°C until use in the actin polymerization assay. For the las17Δ experiment, the extract was diluted one-fourth in XB 200 mM sucrose. For the profilin depletion experiment, 20 μl of the α-Pfy1p serum (∼160 μg of IgG) or an unrelated antibody was preincubated with 15 μl of 50% Protein A-Sepharose in 1 ml of XB buffer for 2 h at 4°C. The buffer was then carefully removed and 15 μl of a LSP BY4741 extract was added to each sample. After incubation for 2 h on ice with occasional shaking, 7 μl of the supernatant was recovered for the actin polymerization assay and 2 μl was analyzed by immunoblot using the α-Pfy1p antibody. For immunoblot analysis of Arp3-MHp, Cof1p, and Pfy1p on the GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads, the reaction for the visual actin polymerization assay was scaled up five times in 35-μm filter disposable minicolumns (Mobicols, M1002; Molecular Biologische Technologie, Goeltingen, Germany) using unlabeled actin from human platelets (APH99; Cytoskeleton). Thirty minutes after addition of the coated Sepharose, the reaction mixture was spun down (at 500g for a few seconds) and the beads were carefully washed three times with 50 μl of XB. The beads were resuspended in 50 μl of SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiled. Ten microliters of each sample were analyzed by immunoblot. As total, 10 μl of a one-tenth dilution of the reaction mixture was loaded.

For the actin pelleting assays, 25 μl of XB 50 mM sucrose containing 2 μM actin from human platelets was incubated for 1 h at room temperature to allow actin polymerization. Twenty-five microliters of XB 50 mM sucrose containing 0, 2, 4, 8, and 16 μM yeast or human cofilin (CFO1A; Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO) was then added and the mixture was further incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Filamentous actin still present in the mixture was recovered by ultracentrifugation for 2 h at 100,000g. Pellets were resuspended in sample buffer and were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. One-third of the total amount of cofilin added per sample was loaded as control.

Visual Actin Polymerization Assay

The actin polymerization assay was designed according to Ma et al. (1998a,b). Briefly, 7 μl of LSP yeast extracts (see above) was mixed with 1 μl of ARS (10 mg/ml creatine kinase, 10 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl2, and 400 mM creatine phosphate), and 1 μl of 10 μM rhodamine-actin (APHR-C; Cytoskeleton), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-actin (APHF-B; Cytoskeleton), or unlabeled actin (APHL99-A; Cytoskeleton) from human platelet (nonmuscle). The polymerization reaction was initiated by adding 1 μl of 50% coated glutathione-Sepharose beads. Samples were incubated at room temperature (26°C) unless otherwise mentioned. For every temperature-sensitive (ts) mutant, the lower temperature at which the extract exhibited a tight defect was used for the final reconstitution experiments. The arp2-2 and arp3-63 mutants exhibited a tight defect already at room temperature, whereas the experiments with the cof1-22 mutant were performed at 30°C. Unless otherwise stated, samples were visualized after 20 to 40 min using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 35; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Latrunculin A (Lat A), DNase I, and Cytochalasin B were added to 10, 16, and 4 μM final concentration, respectively, previous to the addition of the beads. For the reconstitution experiment with the cof1-22 mutant, yeast or human purified cofilin were added to the extracts previous to the addition of other components. For the reconstitution experiments with the arp2 and arp3 mutant extracts, the same preparation of GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads either bound or not to pure Arp2/3 complex were used. For localization of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-Arp3p, the reaction was performed with either unlabeled actin or rhodamine-actin (diluted one-fourth with unlabeled actin to decrease the intensity of the red signal without varying the final actin concentration in the assay). For immunodetection of Cof1p, Tpm1p, and Abp1p on the beads, the reaction was performed with either unlabeled actin or FITC-actin (diluted one-eighth with unlabeled actin to decrease the intensity of the green signal). On incubation, the actin foci were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 20 min. Beads were washed with PBS 0.5%/Tween 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (PBT), and decorated with the appropriate antibody and with a CY3-conjugated secondary antibody in PBT. For labeling of the actin foci with tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate (TRITC)-phalloidin, the reaction was performed with unlabeled actin, fixed as described, washed with PBS, and incubated with 300 nM TRITC-phalloidin (Sigma) in PBS. For immunofluorescence detection of the GST-Myo5-Cp fusion protein, beads were directly decorated with a polyclonal α-Myo5p antibody and a secondary FITC-conjugated α-rabbit immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibody diluted in PBT.

For quantification of the patch density, the patches were counted in at least four different randomly chosen beads per time point and normalized per squared micrometer of bead surface assuming a spherical shape (number of patches/[4πr2/2], where r is the radius of the bead in micrometers). To monitor growth of patches, the diameter of 100 randomly chosen foci in at least four different beads per time point were measured. For visualization of the growth of individual APLS, the visual actin polymerization was performed in a 10-μl flow cell. Antifade solution (2.5 mg/ml glucose, 0.1 mg/ml glucose oxidase, and 0.02 mg/ml catalase; BSM02; Cytoskeleton) was added to reduce photobleaching during imaging.

α-Factor Uptake Assay and Ste2p Degradation

[35S] α-factor uptake assays were performed as described (Dulic et al., 1991). A continuous presence protocol was used. Briefly, cells were grown to 0.5–1 × 107 cells/ml, harvested, and resuspended to 5 × 108 cells/ml in prewarmed (24°C for knockout strains and 37°C for ts strains) YPD bearing 100,000 dpm/ml purified 35S-α-factor. Samples were taken at the indicated time points into ice-cold pH 1 (50 mM sodium citrate) and pH 6 (50 mM potassium phosphate) buffers. Cells were recovered by filtration onto GF/C filters (Whatman, Clifton, NJ) and associated counts were measured in a β-counter (LS 6000 TA; Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA). Internalized counts were calculated by dividing pH 1- by pH 6-resistant counts per time point. Uptake assays were performed at least three times and the mean and SDs were calculated per time point. In any case, the SDs were <10% of the value.

The Ste2p degradation experiment was performed as described (Hicke and Riezman, 1996). Briefly, cells grown to 1 × 107 cells/ml were concentrated fivefold by centrifugation. Cycloheximide was then added to 10 μg/ml and cells were incubated for 10 min (time 0). For the ligand-induced degradation, α-factor was added to of 10−7 M at time 0. Two-milliliter samples were then collected at the indicated times into tubes containing 100 μl of YPD, 200 mM NaN3, and 200 mM NaF on ice. Cells were harvested and glass-bead lysed in 100 μl of 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, and 5 mM EDTA containing PI. One hundred microliters of Thorner buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, 9 M urea, 0.1 mM EDTA 5% SDS, and 5 mM NEM) containing PI was then added, samples were incubated at 37°C for 10 min, and were analyzed by immunoblot using the α-Ste2p antibody.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was performed based on Hicke et al. (1997). Briefly, cells grown to 107 cells/ml were fixed with formaldehyde 3.7% in 100 mM KiPO4, pH 6.5. After 2 h at room temperature, cells were harvested and spheroplasted with Lyticase. Cells were attached to poly-l-lysine coated slides, and incubated 10 min in PBT. Cells were then incubated for 30 min with the primary antibody in PBT, washed with PBT, and incubated for 30 min with the FITC- or CY3-conjugated secondary antibody in PBT. Cells were washed with PBS, mounted in mowiol, and visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

RESULTS

A GST Fusion Protein Bearing the TH2, SH3, and Acidic Domains of Myo5p Induces the Formation of Actin Patch-like Structures (APLS)

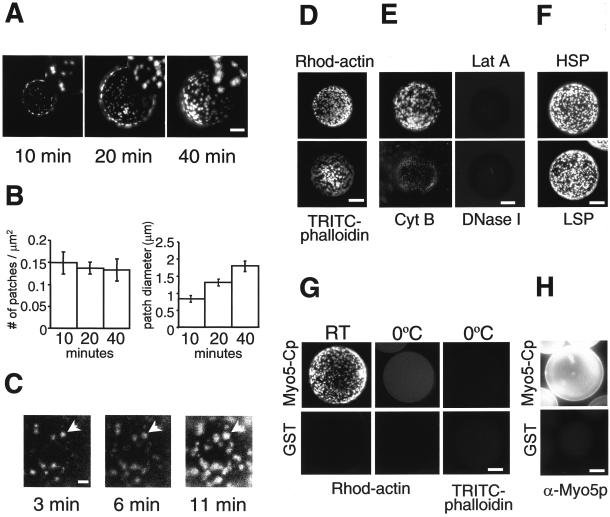

We have recently shown that a GST fusion protein bearing the TH2, SH3, and acidic domains of Myo5p (GST-Myo5-Cp, bearing residue 984-1219 of Myo5p) induces cytosol-dependent actin polymerization on glutathione-Sepharose beads (Geli et al., 2000). Actin polymerization is monitored by fluorescence microscopy in the presence of rhodamine-actin. Strikingly, when we followed the reaction on the coated beads within short incubation times, we found that the rhodamine-actin signal appeared as distinct foci that grew laterally (Figure 1A-C). The fluorescent structures were confirmed to contain F-actin because they could be labeled with TRITC-phalloidin (Figure 1D). Consistently, the actin-depolymerizing drugs Lat A, DNase I, or cytochalasin B prevented the appearance of the actin foci (Figure 1E). High-speed ultracentrifugation of the yeast extracts previous to the addition of the beads had no obvious effect on the reaction, suggesting that formation of the actin foci did not require prepolymerized actin (Figure 1F). Next, we investigated whether Myo5-Cp actually induced actin polymerization or whether actin spontaneously polymerized in the extract during the incubation and subsequently bound the coated beads. For that purpose, actin was allowed to polymerize in the presence of extract, but in the absence of beads. After cooling the sample on ice, beads were added and the mixture was further incubated at 0°C for 30 min to allow interaction of preformed filaments to the fusion protein. As shown in Figure 1G, no actin foci were formed under these conditions. Interestingly, a weak and homogeneous fluorescent signal was detected when compared with the GST control. However, actin bound to the GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads under these conditions could not be decorated with TRITC-phalloidin, suggesting that it was G-actin (Figure 1G). This experiment also indicated that GST-Myo5-Cp was evenly distributed on the beads. Indeed, an antibody against the C terminus of Myo5p homogeneously decorated the beads (Figure 1H), demonstrating that the actin foci did not result from the uneven distribution of the fusion protein.

Figure 1.

Fluorescence micrographs of actin foci formed on beads coated with a GST fusion protein bearing the TH2, SH3, and acidic domains of Myo5p (residues 984-1219; GST-Myo5-Cp). (A) GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads incubated with an extract from a wild-type strain (RH2881) and 1 μM rhodamine-actin for the indicated times. Magnified areas are shown at the upper right. (B) Average density and size of individual foci as a function of time. (C) Time-lapse microscopy showing growth of individual rhodamine-actin foci (arrows). (D) GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads incubated with an extract from a wild-type strain (RH2881) and either 1 μM rhodamine-actin (Rhod-actin) or unlabeled actin (TRITC-phalloidin) from the same source, fixed, and unlabeled F-actin decorated with TRITC-phalloidin. (E) GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads incubated with an extract from a wild-type strain (RH2881) and 1 μM rhodamine-actin in the absence or presence of 10 μM Lat A, 16 μM DNase I, or 4 μM Cytochalasin B (CytB). (F) GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads incubated with 1 μM rhodamine-actin and an extract from a wild-type strain (RH2881; LSP) or the same extract after four times ultracentrifugation at 100,000g for 1 h to eliminate filamentous actin (HSP). (G) GST or GST-Myo5Cp-coated beads incubated at 0°C with an extract from a wild-type strain (RH2881) and 1 μM rhodamine-actin (Rho-actin) or unlabeled actin (TRICT-phalloidin) from the same source, after actin polymerization was allowed to occur at room temperature in the absence of beads (0°C). Unlabeled filamentous actin was decorated with TRITC-phalloidin. Actin foci generated under standard conditions were stable after 30 min incubation on ice (room temperature). (H) GST or GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads decorated with an α-Myo5p antibody and a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. Bar, 10 μm.

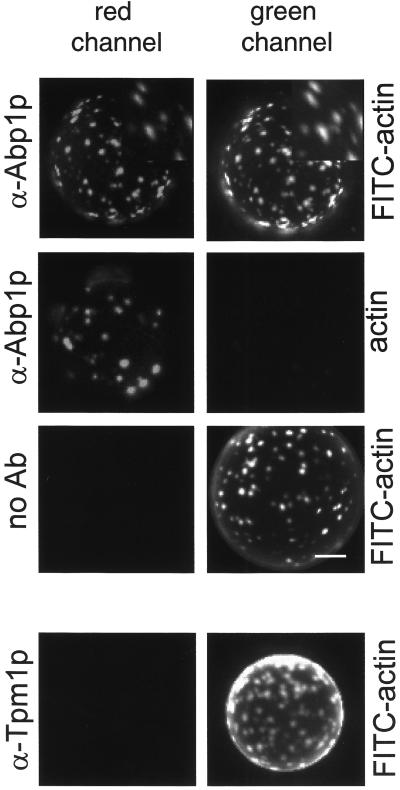

At the resolution offered by the fluorescence microscopy, the Myo5-Cp-induced actin foci were reminiscent of the yeast cortical actin patches. To analyze whether the in vitro-generated structures represented the simple accumulation of filamentous actin or a more complex cytoskeletal organization, we investigated the presence of Abp1p, a marker of the yeast cortical actin patches (Mulholland et al., 1994). Interestingly, we found that the myosin-I-induced actin foci could be decorated with an antibody against Abp1p, whereas we failed to detect tropomyosin (Tpm1p), a protein that also binds F-actin but does not localize to the cortical actin patches in vivo (Liu and Bretscher, 1989; Figure 2). These results suggested that Myo5p induced the formation of APLS in vitro.

Figure 2.

The Myo5-Cp-induced actin foci contain Abp1p. Fluorescence micrographs of GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads incubated with 1 μM FITC-actin or unlabeled actin from the same source and an extract from a wild-type strain (RH2881), fixed, and decorated with α-Abp1p or α-Tpm1p antibodies or no primary antibody (no Ab) and a CY3-conjugated secondary antibody. The same beads were photographed using appropriate filters to visualize the FITC and CY3 fluorescent signals. Magnified areas showing colocalization of Abp1p and actin are shown at the top right. Bar, 10 μm.

The ARP2/3 Complex Is Required But Not Sufficient to Generate The Myo5p-Induced APLS

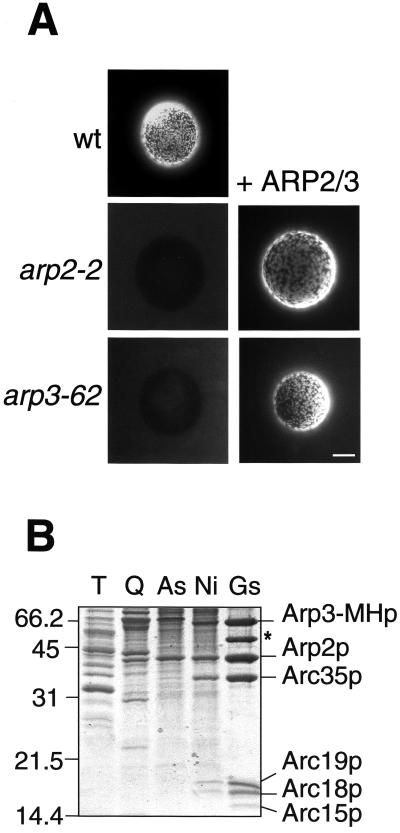

The Arp2/3 complex has been implicated in the generation and dynamics of the cortical actin patches in yeast (Winter et al., 1997) and, like actin and the myosins-I, it is required for endocytic uptake (Moreau et al., 1997; Schaerer-Brodbeck and Riezman, 2000). To investigate whether the Arp2/3 complex was involved in the generation of the Myo5p-induced APLS, we prepared extracts from arp2 (arp2-2) and arp3 (arp3-62) mutants and tested their ability to form these structures. As shown in Figure 3A, both extracts were defective. To demonstrate that misfunctioning of the Arp2/3 complex directly caused the observed defects, we performed a reconstitution assay. Addition of purified Arp2/3 complex to the reaction (Figure 3B) fully restored the ability of the arp2 and arp3 mutant extracts to form the APLS (Figure 3A). Consistent with a direct role of the Arp2/3 complex in the process, Arp3p tagged with GFP (GFP-Arp3p) colocalized with the rhodamine-labeled foci (Figure 4A). Interestingly, we also found that GFP-Arp3p evenly decorated the surface of the coated beads. The even staining (but not the GFP-Arp3p patches) was resistant to treatment with Lat A, suggesting that such interaction was not actin dependent (Figure 4B). Consistently, myc-tagged Arp3p (Arp3-MHp), but not actin, was efficiently pulled down with GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads when Lat A was added to the assay (Figure 4B).

Figure 3.

The Arp2/3 complex is required for the formation of the Myo5p-induced APLS. (A) Fluorescence micrographs of GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads (left) or GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads prebound to purified Arp2/3 complex (right) incubated with 1 μM rhodamine-actin and extracts from a wild-type strain (RH2881; wt), ts arp2 (RH4165; arp2-2), or arp3 (RH4166; arp3-62) mutants. Bar, 10 μm (B) Purification of the Arp2/3 complex from a yeast strain expressing a 6His- and myc-tagged Arp3p (Arp3-MHp; strain RH4147). Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel showing equal amounts of protein from the total yeast cell lysate (T), the Q-Sepharose eluate (Q), the 40% ammonium sulfate precipitate (As), the Ni-Sepharose eluate (Ni), and the GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads bound to the purified Arp2/3 complex used in the in vitro assay (Gs). The asterisk shows the GST-Myo5-Cp.

Figure 4.

Arp3p colocalizes with the Myo5-Cp-induced APLS. (A) Fluorescence micrographs of GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads incubated with 1 μM rhodamine-actin or unlabeled actin of the same source and extracts from a wild-type strain (RH2881; Arp3p) or a strain expressing GFP-tagged Arp3p (RH4149; GFP-Arp3p). The same beads were photographed using appropriate filters to visualize the GFP and rhodamine fluorescent signals. Magnified areas demonstrating colocalization of Arp3p and actin are shown at the top right. (B) Fluorescence micrographs (top) and immunoblot analysis (bottom) of GST or GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads incubated with 1 μM unlabeled actin and extracts from strains expressing GFP-tagged Arp3p (RH4149; GFP-Arp3p, top) or myc-tagged Arp3p (RH4157; Arp3-MHp, bottom) extracts. Ten micromoles Lat A was added to the indicated samples. The C9 α-myc and C4 α-actin antibodies were used for immunodetection of Arp3-MHp and actin (bottom). GST and GST-Myo5-Cp were visualized with Ponceau red (bottom). One-tenth of the total reaction mixture was loaded for comparison (T). Bar, 10 μm.

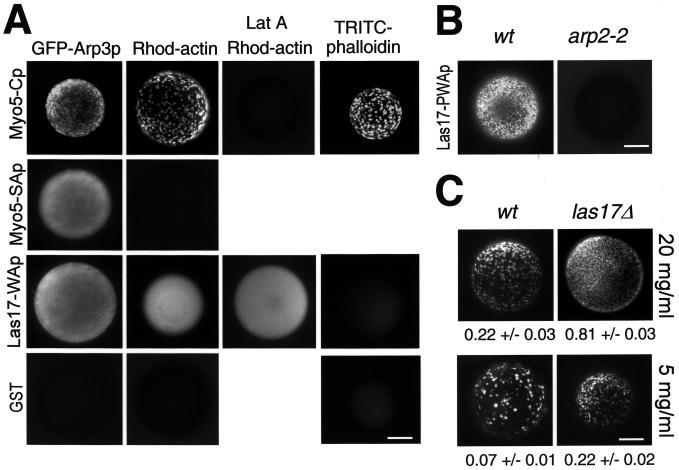

The even GFP-Arp3p staining was similar to that of the Myo5-Cp immunolocalization experiment (Figure 4B compared with Figure 1H), indicating that mere association of Myo5p to the Arp2/3 complex was insufficient to initiate the process. Actually, a GST fusion protein bearing the Myo5p SH3 and acidic domains and lacking the TH2 domain [Myo5-(SA)p, including residues 1085–1219 of Myo5p] efficiently bound the complex but was unable to induce the formation of actin foci (Figure 5A). Furthermore, a GST fusion protein bearing the WH2 and acidic domains of Las17p (GST-Las17-WAp, including residues 417–634 of Las17p), which efficiently activates purified Arp2/3 (Winter et al., 1999a), also interacted with GFP-Arp3p but failed to induce the formation of APLS in our in vitro assay (Figure 5A). Nevertheless, beads coated with GST-Las17-WAp were evenly decorated with rhodamine-actin. In contrast to the myosin-I-induced APLS, however, the rhodamine staining was resistant to treatment with Lat A, and the beads could not be decorated with TRITC-phalloidin (Figure 5A). This observation is consistent with previous reports demonstrating that the WH2 domain binds monomeric actin (Higgs and Pollard, 1999; Madania et al., 1999). These data suggested that the formation of the Myo5p-induced APLS might be a complex process involving other cellular factors beside actin and the Arp2/3 complex.

Figure 5.

Recruitment of the Arp2/3 complex is not sufficient to trigger the formation of APLS. (A) Fluorescence micrographs of beads coated with GST, GST-Myo5-Cp, or GST fusion proteins bearing the SH3 and acidic domains of Myo5p (residues 1085–1219; Myo5-SAp) or the WH2 and acidic domains of Las17p (residues 417–634; Las17-WAp) incubated with 1 μM rhodamine-actin (Rhod-actin) or unlabeled actin from the same source (GFP-Arp3p and TRITC-phalloidin) and extracts from a wild-type strain (RH2881; Rhod-actin and TRITC-phalloidin) or a strain expressing GFP-tagged Arp3p (RH4149; GFP-Arp3p). Ten micromoles Lat A was added to the indicated samples. Unlabeled F-actin was decorated with TRITC-phalloidin in the experiment shown in the right panels. (B) Fluorescence micrographs of beads coated with a GST fusion protein bearing the polyP-rich, WH2, and acidic domains of Las17p (residues 316–634; Las17-PWAp) incubated with an extract from a wild-type strain (RH2881; wt) or an arp2 mutant (RH4165; arp2-2). (C) Fluorescence micrographs of GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads incubated with 1 μM rhodamine-actin and an extract from a wild-type strain (RH2881; wt) or a strain lacking Las17p (IDY223; las17Δ) under standard conditions (20 mg/ml) or after diluting the extract to 5 mg/ml. The average and SDs of the number of foci per square micrometer of bead surface are given for each experiment. Bar, 10 μm.

Genetic evidence indicates that the myosins-I and Las17p are functionally redundant (Evangelista et al., 2000). Therefore, it was surprising that the GST-Las17-WAp fusion protein was unable to induce the formation of APLS. Interestingly, it was recently shown that in addition to the WH2 and acidic domains, WASP-induced generation of actin foci at the plasma membrane requires the polyP-rich domain (Castellano et al., 2001). In agreement with this observation, we found that a larger GST fusion protein containing the polyP-rich, the WH2, and the acidic domains of Las17p (Las17-PWAp, residues 316–634) efficiently induced Arp2p-dependent actin foci similar to those induced by Myo5p (Figure 5B). These data suggested that Las17p also induced the formation of APLS in yeast extracts. To investigate whether Myo5p would work by recruiting Las17p to the beads that in turn would then activate Arp2/3-dependent actin polymerization, we tested the ability of a strain lacking Las17p (las17Δ) to sustain the formation of Myo5p-induced APLS in vitro. Consistent with the genetic observations suggesting functional redundancy, we found that Myo5p could still induce the formation of APLS in the absence of Las17p (Figure 5C).

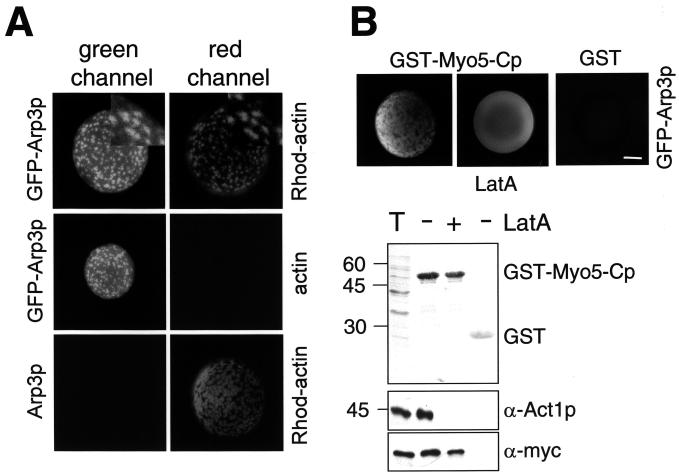

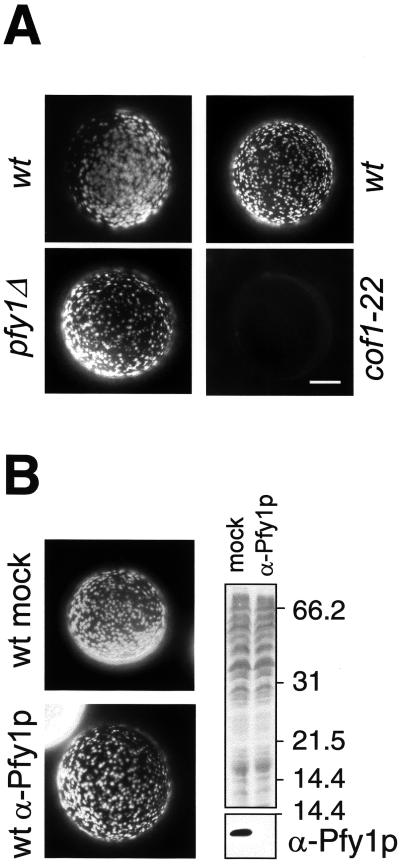

Cofilin, But Not Profilin, Is Required to Generate Myo5p-Induced APLS

Robust genetic and biochemical evidence indicates that cofilin (Cof1p) and profilin (Pfy1p) cooperate in yeast to sustain a rapid actin filament turnover (Belmont and Drubin, 1998). Besides, mutations in the genes encoding cofilin (COF1) and profilin (PFY1) cause severe defects in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton and in endocytosis (Lappalainen and Drubin, 1997; Wolven et al., 2000). Therefore, we predicted that cofilin and profilin would also be required to generate the myosin-I-induced APLS. To investigate this matter, we tested cell extracts from a ts cofilin mutant (cof1-22) and a profilin-deleted strain (pfy1Δ) in our in vitro assay. Interestingly, we found that whereas the extract from the cofilin mutant exhibited a strong defect in its ability to form the myosin-I-induced APLS, depletion of cellular profilin had no effect in the assay (Figure 6A). Deletion of profilin causes aberrant cell morphology and a severe growth defect in yeast (Wolven et al., 2000). Thus, to rule out that the profilin-deleted strain had overcome the lack of profilin by adjusting the cytosolic concentration of actin or other actin-associated proteins, we also assayed a cell extract from a wild-type strain that immunodepleted from this protein. As for the extract from the profilin-deleted strain, no defect was observed when compared with the mock-depleted extract (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Cofilin, but not profilin, is required for the generation of Myo5-Cp-induced APLS. (A) Fluorescence micrographs of GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads incubated with 1 μM rhodamine-actin and extracts from wild-type strains (SCMIG100, left; DDY1252, right; wt), a profilin-deleted (SCMIG426; pfy1Δ), or a ts cofilin mutant (DDY1266; cof1-22). The experiment with the cofilin mutant was performed at 30°C. (B) Fluorescence micrographs of GST- Myo5-Cp-coated beads incubated with 1 μM rhodamine-actin and extracts from a wild-type strain (BY4147; wt) preincubated with Protein A-Sepharose bound to either an α-profilin (α-Pfy1p) or an unrelated antibody (mock). The right panel shows the immunoblot analysis of the profilin (α-Pfy1p) or mock-depleted (mock) extracts using the α-Pfy1p antibody (bottom). Total proteins were stained with Ponceau red. Bar, 10 μm.

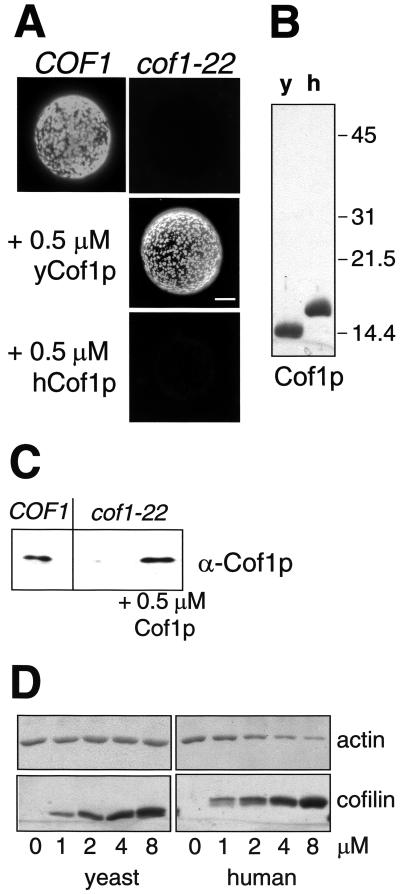

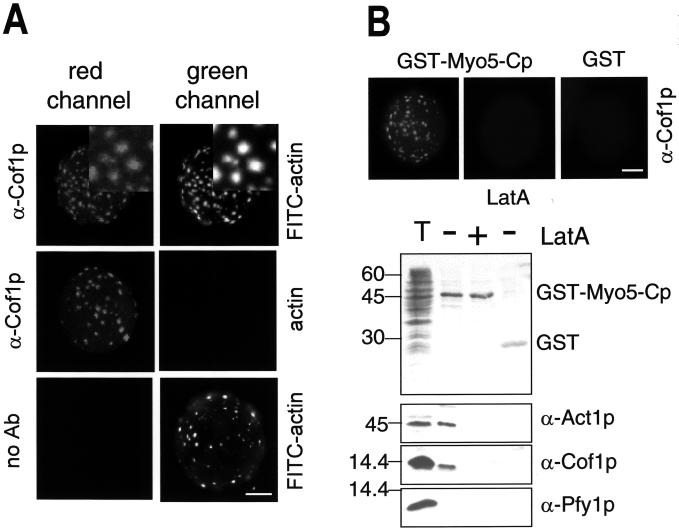

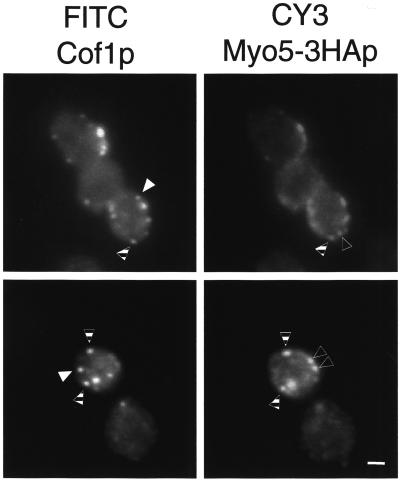

The inability of the cofilin mutant to form the Myo5p-induced APLS suggested that cofilin might directly be involved in the process. To rule out that a secondary defect in the mutant strain caused the observed phenotype, we performed a reconstitution assay by adding recombinant purified yeast cofilin (Cof1p) to final concentrations of 0.05, 0075, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2.5, and 5 μM. We found that the addition of yeast cofilin between 0.5 and 1 μM (Figure 7B) completely restored formation of the APLS in the cofilin mutant extract (Figure 7A). Immunoblot analysis indicated that the reconstitution occurred at approximately the physiological cofilin concentration (Figure 7C). Interestingly, addition of recombinant purified human cofilin failed to reconstitute the formation of the APLS in the cofilin mutant extract at any of the mentioned concentrations (0.05, 0075, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2.5, and 5 μM). This was in spite of human cofilin being more efficient than yeast cofilin to disassemble actin filaments in the conditions used in the assay (Figure 7D). These results suggested that cofilin played a direct role in the formation of the Myo5p-induced APLS in vitro. Consistently, cofilin colocalized with the myosin-I-induced APLS (Figure 8A), and cofilin, but not profilin, could be pulled down with GST-Myo5-Cp and actin in conditions that allowed formation of APLS (Figure 8B). In contrast to the Arp2/3 complex, however, the addition of Lat A disrupted the interaction, suggesting that the cofilin/Myo5p interaction was actin dependent (Figure 8B). To investigate whether the myosins-I and cofilin cooperate in vivo to form the actin patches, we investigated if these two proteins colocalized in yeast by immunofluorescence. As previously described, cofilin and Myo5p appeared concentrated in cortical patches that, for cofilin, colocalize with cortical actin patches (Anderson et al., 1998; Rodal et al., 1999). Interestingly, we found that some of the cofilin patches strikingly colocalized with the Myo5p signal. However, foci exclusively labeled with Myo5p or cofilin could also be observed (Figure 9). These results suggested that either the functional interaction between cofilin and Myo5p was transient and different foci represented distinct stages in the formation of a dynamic cellular structure or different types of cortical actin patches might exist that fulfill distinct cellular functions.

Figure 7.

Recombinant purified yeast cofilin rescues the ability of the cofilin mutant extract to sustain the formation of Myo5-Cp-induced APLS. (A) Fluorescence micrographs of GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads incubated with 1 μM rhodamine-actin and extracts from a wild-type strain (DDY1252; COF1) or a ts cofilin mutant (DDY1266; cof1-22) in the presence or absence of 0.5 μM recombinant purified yeast (yCof1p) or human cofilin (hCof1p) Bar, 10 μm. (B) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of recombinant purified yeast (y) or human (h) cofilins (Cof1p) used in the bead assay. (C) Immunoblot analysis of the cofilin present in the COF1, cof1-22, and cof1-22 + 0.5 μM yCof1p samples. (D) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of pelletable (at 100,000g for 2 h) filamentous actin still present in the samples after incubation of 1 μM prepolymerized unlabeled actin with increasing concentrations of recombinant purified yeast or human cofilin. The bottom panel shows one-third of the total amount of cofilin added per sample.

Figure 8.

Cofilin colocalizes with the in vitro-generated Myo5p-induced APLS. (A) Fluorescence micrographs of GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads incubated with 1 μM FITC-actin or unlabeled actin from the same source and an extract from a wild-type strain (DDY1252), fixed, and decorated with either an α-cofilin antibody (α-Cof1p) or no primary antibody (no Ab) and a CY3-conjugated secondary antibody. The same beads were photographed using appropriate filters to visualize the FITC and CY3 fluorescent signals. Magnified areas demonstrating colocalization of cofilin and actin are shown at the top right. (B) Fluorescence micrographs (top) and immunoblot analysis (bottom) of GST- and GST-Myo5-Cp-coated beads incubated with 1 μM unlabeled actin and an extract from a wild-type strain (DDY1252). Tem micromoles Lat A was added to the indicated samples. Beads were fixed and decorated with an α-Cof1p and a CY3-conjugated secondary antibody for immunofluorescence (top). The α-Cof1p, α-Pfy1p and C4 antibodies were used for immunodetection of cofilin, profilin, and actin on the nitrocellulose filters (bottom). One-tenth of the total reaction mixture (T) was loaded for comparison. GST and GST-Myo5-Cp were visualized with Ponceau red. Bar, 10 μm.

Figure 9.

Cofilin and Myo5p colocalize in a subset of cortical patches in vivo. Fluorescence micrographs of yeast cells expressing a 3HA-tagged Myo5p (Myo5–3HAp; SCMIG275 cells bearing the p33MYO5–3HA plasmid), fixed, and decorated with rabbit α-cofilin (Cof1p) and rat α-HA antibodies and FITC-conjugated α-rabbit IgG (FITC Cof1p) and CY3-conjugated α-rat IgG antibodies (CY3 Myo5–3HAp). The same cells were photographed using appropriate filters to visualize the FITC and CY3 fluorescent signals. Dashed arrowheads point to cortical patches showing colocalization of cofilin and Myo5p. Filled and empty arrowheads point to cortical patches exclusively containing cofilin or Myo5p, respectively. Bar, 1 μm.

Cofilin, But Not Profilin, Is Required for the Endocytic Uptake in Yeast

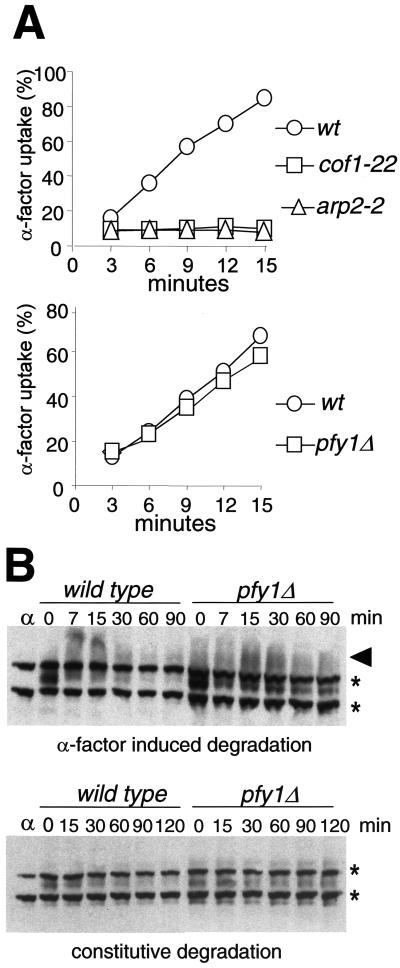

Our data suggested that the function of cofilin and profilin could be separated in vitro. Yet, robust genetic evidence demonstrates that cofilin and profilin cooperate in vivo to maintain a rapid actin filament turnover (Wolven et al., 2000), and they both participate in endocytosis (Lappalainen and Drubin, 1997; Wolven et al., 2000). The endocytic defects of the cofilin and profilin mutants have been examined by monitoring accumulation of the fluid-phase marker Lucifer yellow in the vacuole (Lappalainen and Drubin, 1997; Wolven et al., 2000). Not only mutations that block the endocytic uptake, but also those that impede trafficking along the endosomal compartments cause defective vacuolar accumulation of this fluorescent dye (Riezman et al., 1996). The generation of the primary endocytic vesicles at the plasma membrane requires the myosins-I (Geli and Riezman, 1996) and the Arp2/3 complex (Moreau et al., 1997; Schaerer-Brodbeck and Riezman, 2000) and might be associated with the cortical actin patches (Pruyne and Bretscher, 2000). Thus, we predicted that cofilin would be involved in the uptake step of endocytosis, whereas profilin mutants might block a postinternalization step. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the ability of the cofilin (cof1-22) and profilin mutants (pfy1Δ) to internalize radiolabeled α-factor. The α-factor internalization assay quantitatively measures the endocytic uptake at the plasma membrane (Dulic et al., 1991). As predicted by our in vitro data, the ts cofilin mutant (cof1-22) exhibited an immediate and potent endocytic defect upon shift to the restrictive temperature (Figure 10A). The internalization block was analogous to that observed in the arp2 mutant (arp2-2) and that previously described for actin (Kubler and Riezman, 1993) and myosin-I mutants (Geli and Riezman, 1998). In contrast, the strain lacking profilin (pfy1Δ) did not exhibit a significant uptake defect when compared with the isogenic wild type (Figure 10A).

Figure 10.

Cofilin, but not profilin, is required for the endocytic uptake in yeast. (A) 35S-labeled α-factor internalization kinetics of arp2 (strain RH4165; arp2-2), cofilin (strain SCMIG134; cof1-22), and profilin (strain SCMIG426; pfy1Δ) mutant strains, and the isogenic wild-type strains (RH2881; higher panel and SCMIG100; lower panel). Percentage of cell-associated counts (pH 6 resistant, approximately 2000 cpm) internalized (pH 1 resistant) per time point. The assays were performed at 37°C for ts strains and the isogenic wild type (top) and at 24°C for the profilin-deleted strain and the isogenic wild type (bottom). (B) Immunoblot analysis of constitutive (bottom) and ligand-induced (top) degradation of the α-factor receptor Ste2p in a profilin-deleted strain (SCMIG426; pfy1Δ) and the isogenic wild type (SCMIG100). The first time point (0) was taken 10 min upon addition of cycloheximide. α-factor was added at time 0 in the experiment shown in the top panel (ligand-induced degradation). The arrow points to hyperphosphorylated and ubiquitinated receptor. The stars indicate two crossreactive bands. A protein extract from a Matα strain that does not express Ste2p was loaded to control the specificity of the antibody (α).

The in vivo and in vitro data strongly indicated that profilin might participate in a postinternalization step within the endocytic pathway, which might not be related to the formation of myosin-I-induced APLS. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that even though the α-factor internalization was unaffected in the profilin deleted strain (pfy1Δ), ligand-induced and constitutive degradation of the α-factor receptor (Ste2p), and thus, endocytic traffic to the vacuole, was delayed in this mutant with respect to the isogenic wt (Figure 10B).

DISCUSSION

Myo5p Induces the Formation of APLS In Vitro That Might Be Mechanistically Significant for the Endocytic Uptake In Vivo

The data presented in this manuscript demonstrate that Myo5p can induce the formation of cytosol-dependent actin foci in vitro, which might recapitulate the yeast cortical actin patches. The Myo5p-induced actin foci contained markers of the yeast cortical actin patches, Abp1p, Arp3p, and cofilin, whereas they seemed devoid of tropomyosin (Tmp1p), a protein that exclusively localizes to the actin cables (Mulholland et al., 1994; Pruyne and Bretscher, 2000). Interestingly, it was recently demonstrated that two distinct actin-nucleating complexes exist in yeast that might be responsible for the generation of the cortical actin patches or the actin cables (Evangelista et al., 2002; Sagot et al., 2002). The generation of the actin patches seems to depend on the Arp2/3 complex (Evangelista et al., 2002), whereas the yeast formins (Bni1p and Bnr1p) and profilin are involved in the generation of the actin cables (Evangelista et al., 2002; Sagot et al., 2002). Consistent with the hypothesis that Myo5p specifically induces the formation of actin patches in vitro, we have demonstrated that the Arp2/3 complex, but not profilin, is required in the process.

The formation of the myosin-I-induced APLS appears to be a complex process that requires multiple protein-protein interactions. We previously showed that the Myo5p SH3 domain is required to sustain myosin-I-induced actin polymerization (Geli et al., 2000). The SH3-mediated interaction of Myo5p with Vrp1p might explain this requirement. Interestingly, it was recently demonstrated that a fusion protein containing the Vrp1p WH2 and Myo3p acidic domains efficiently activates the actin nucleating activity of purified Arp2/3 complex (Lechler et al., 2001). Another possibility would be that the Myo5p SH3 domain recruits Las17p (Evangelista et al., 2000; Lechler et al., 2000), which then would activate the Arp2/3 complex and induce the formation of the actin patches. However, our results demonstrate that this is actually not the case because a yeast extract from a strain lacking Las17p is still able to sustain the formation of Myo5p-induced APLS. This result is consistent with the genetic observation that the acidic peptides of the yeast myosins-I and Las17p are functionally redundant and, therefore, the myosins-I should activate Arp2/3-dependent polymerization in the absence of Las17p.

In addition to the SH3 domain, we demonstrate now that the Myo5p TH2 domain is necessary to form the APLS in vitro, and binding to and activation of the Arp2/3 complex is not sufficient to sustain the process. A binding partner for the Myo5p TH2 domain that could explain this requirement has not yet been identified. Another intriguing observation is that even though the GST-Myo5-Cp fusion protein and the Arp2/3 complex evenly decorated the surface of the Sepharose beads, the formation of APLS was initiated in a limited number of sites that did not significantly increase with time. Actin is not limiting in the assay because the individual APLS continue to grow over time. These results strongly suggest that a cytosolic factor other than the Arp2/3 complex and actin itself might limit the initiation of the process. The observation that the cytosol of the strain lacking Las17p sustained the formation of a significant higher density of APLS suggests that the limiting factor might be a Las17p interacting partner, which could be more available in the absence of Las17p (Figure 5C).

Thus far, all proteins involved in the formation of the myosin-I-induced APLS in vitro (actin, the myosins-I, the Arp2/3 complex, cofilin, and Vrp1p) are required for the endocytic uptake, and they localize to cortical patches in yeast (Pruyne and Bretscher, 2000). These data suggest that we are reconstituting in vitro a process that is functionally significant for the endocytic uptake in vivo. Interestingly, at least some of the cortical actin patches appear at the ultrastructural level as deep (150–250 nm) actin-coated plasma membrane invaginations of 45 nm in diameter (Mulholland et al., 1994). Beside, the primary endocytic vesicles that accumulate in a sec18 mutant have an average diameter of 30–50 nm (Prescianotto-Baschong and Riezman, 1998), similar to that of the cortical actin patches. Regardless of whether the cortical actin patches are the direct precursors of the primary endocytic profiles, a similar mechanism is likely to be involved in their generation because both the size of the structures and the machinery involved in their generation is similar. Generation of the primary endocytic vesicles might then require additional proteins to complete fission of the membrane invagination. The conditions established in our in vitro assay now provide the tools to reproduce the formation of myosin-I-induced APLS on artificial liposomes and directly test if the generation of an actin coat is linked to the deformation of the lipid bilayer.

A Profilin-independent Cellular Role for Cofilin

A number of results indicate that cofilin and profilin cooperate to enhance the actin filament turnover in vitro and in vivo (Carlier et al., 1997; Kang et al., 1997; Rosenblatt et al., 1997; Didry et al. 1998; Loisel et al. 1999; Mimuro et al., 2000). However, our data suggest that cofilin plays an additional role in the endocytic uptake that does not require profilin and therefore might not be related to vectorial depolymerization of actin. We found that a ts cofilin mutant is unable to internalize the α-factor pheromone at restrictive temperature. In contrast, depletion or mutation of profilin had a minor effect in the process. These results are remarkably significant because deletion of profilin causes severe growth and morphology defects and striking disorganization of the actin cytoskeleton. These results further demonstrate that actin plays a specific role in the uptake step of endocytosis that might be related to the formation of a cytoskeletal structure (i.e., the cortical actin patches) composed of a particular set of actin-associated proteins. Consistent with the hypothesis that Myo5p induces the formation of a structure that is functionally relevant for the endocytic budding, we have found that cofilin, but not profilin, is required to assemble the APLS in vitro. The role of cofilin in the generation of the APLS did not exclusively (if at all) rely on its ability to disassemble actin because a human cofilin, which efficiently severed and/or depolymerized actin filaments in the conditions used in the assay, failed to reconstitute the formation of the APLS in the ts cofilin mutant extract. These data, together with the subcellular localization of cofilin to the cortical actin patches in yeast, suggest that the function of cofilin in the endocytic uptake might be related to the generation of cortical actin patches. The profilin-independent role of cofilin in the generation of these structures could still be directly related to its severing activity, which might induce actin polymerization rather than depolymerization under certain circumstances (Chan et al., 2000). Alternatively, cofilin might be involved in remodeling of branched actin-Arp2/3 networks at the plasma membrane (Blanchoin et al., 2000).

Finally, our data suggest that profilin might play a role in a postinternalization step in the endocytic pathway that could explain the poor accumulation of Lucifer Yellow in the vacuoles of profilin mutants. Interestingly, micropinocytic profiles in mast cells are propelled into the cytosol at the tip of actin tails at the moment they pinch off from the plasma membrane (Merrifield et al., 1999). In addition, it was recently shown that endocytic organelles can trigger formation of actin comets in cell extracts (Taunton et al., 2000). Thus, the role of profilin within the endocytic pathway might be related to the generation of actin comets/cables involved in the final release of the primary endocytic vesicle from the plasma membrane or their transport to the endosomal compartments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the laboratory, J. Ortiz, and H. Riezman for discussion and improvement on the manuscript. We are grateful to D. Drubin, A. Bretscher, and H. Riezman for sending material. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant SFB 352).

Abbreviations used:

- TH1

tail homology domain

- WASP

Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein

- Lat A

Latrunculin A

- APLS

actin patch-like structures

- GST

glutathione-S-transferase

- GFP

green fluorescent proteins

- YPD

yeast peptone dextrose

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- HA

hemagglutinin

- LSP

low-speed pelleted

- HSP

high-speed pelleted

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- wt

wild-type

- ts

temperature sensitive

- PBT

PBS 0.5%/Tween 0.1 mg/ml

- TRITC

tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate

- Ig

immunoglobulin

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.02–04–0052. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.02–04–0052.

REFERENCES

- Anderson BL, Boldogh I, Evangelista M, Boone C, Greene LA, Pon LA. The Src homology domain 3 (SH3) of a yeast type I myosin, Myo5p, binds to verprolin and is required for targeting to sites of actin polarization. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1357–1370. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.6.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchoin L, Pollard TD, Mullins RD. Interactions of ADF/cofilin, Arp2/3 complex, capping protein and profilin in remodeling of branched actin filament networks. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1273–1282. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00749-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmont LD, Drubin DG. The yeast V159N actin mutant reveals roles for actin dynamics in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:1289–1299. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.5.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlier MF, Laurent V, Santolini J, Melki R, Didry D, Xia GX, Hong Y, Chua NH, Pantaloni D. Actin depolymerizing factor (ADF/cofilin) enhances the rate of filament turnover: implication in actin-based motility. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:1307–1322. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano F, Le Clainche C, Patin D, Carlier MF, Chavrier P. A WASp-VASP complex regulates actin polymerization at the plasma membrane. EMBO J. 2001;20:5603–5614. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.20.5603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AY, Bailly M, Zebda N, Segall JE, Condeelis JS. Role of cofilin in epidermal growth factor-stimulated actin polymerization and lamellipod protrusion. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:531–542. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didry D, Carlier MF, Pantaloni D. Synergy between actin depolymerizing factor/cofilin and profilin in increasing actin filament turnover. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25602–25611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dower WJ, Miller JF, Ragsdale CW. High efficiency transformation of E. coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:6127–6145. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.13.6127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulic V, Egerton M, Elguindi I, Raths S, Singer B, Riezman H. Yeast endocytosis assays. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:697–710. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94051-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrbach A, Collins K, Matsudaira P, Louvard D, Coudrier E. Brush border myosin-I truncated in the motor domain impairs the distribution and the function of endocytic compartments in an hepatoma cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7053–7058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrbach A, Raposo G, Tenza D, Louvard D, Coudrier E. Truncated brush border myosin I affects membrane traffic in polarized epithelial cells. Traffic. 2000;1:411–424. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista M, Klebl BM, Tong AH, Webb BA, Leeuw T, Leberer E, Whiteway M, Thomas DY, Boone C. A role for myosin-I in actin assembly through interactions with Vrp1p, Bee1p, and the Arp2/3 complex. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:353–362. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.2.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista M, Pruyne D, Amberg DC, Boone C, Bretscher A. Formins direct Arp2/3-independent actin filament assembly to polarize cell growth in yeast. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:32–41. doi: 10.1038/ncb718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geli MI, Lombardi R, Schmelzl B, Riezman H. An intact SH3 domain is required for myosin I-induced actin polymerization. EMBO J. 2000;19:4281–4291. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geli MI, Riezman H. Role of type I myosins in receptor-mediated endocytosis in yeast. Science. 1996;272:533–535. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5261.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geli MI, Riezman H. Endocytic internalization in yeast and animal cells: similar and different. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:1031–1037. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.8.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geli MI, Wesp A, Riezman H. Distinct functions of calmodulin are required for the uptake step of receptor-mediated endocytosis in yeast: the type I myosin Myo5p is one of the calmodulin targets. EMBO J. 1998;17:635–647. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.3.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson HV, Anderson BL, Warrick HM, Pon LA, Spudich JA. Synthetic lethality screen identifies a novel yeast myosin I gene (MYO5): myosin I proteins are required for polarization of the actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:1277–1291. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke L, Riezman H. Ubiquitination of a yeast plasma membrane receptor signals its ligand- stimulated endocytosis. Cell. 1996;84:277–287. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80982-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke L, Zanolari B, Pypaert M, Rohrer J, Riezman H. Transport through the yeast endocytic pathway occurs through morphologically distinct compartments and requires an active secretory pathway and Sec18p/N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:13–31. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs HN, Pollard TD. Regulation of actin polymerization by Arp2/3 complex and WASp/Scar proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32531–32534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber LA, Fialka I, Paiha K, Hunziker W, Sacks DB, Bahler M, Way M, Gagescu R, Gruenberg J. Both calmodulin and the unconventional myosin Myr4 regulate membrane trafficking along the recycling pathway of MDCK cells. Traffic. 2000;1:494–503. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H, Fukuda Y, Murata K, Kimura A. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung G, Wu X, Hammer JA., III Dictyostelium mutants lacking multiple classic myosin I isoforms reveal combinations of shared and distinct functions [see comments] J Cell Biol. 1996;133:305–323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang F, Laine RO, Bubb MR, Southwick FS, Purich DL. Profilin interacts with the Gly-Pro-Pro-Pro-Pro-Pro sequences of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP): implications for actin- based Listeria motility. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8384–8392. doi: 10.1021/bi970065n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubler E, Riezman H. Actin and fimbrin are required for the internalization step of endocytosis in yeast. EMBO J. 1993;12:2855–2862. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05947.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen P, Drubin DG. Cofilin promotes rapid actin filament turnover in vivo. Nature. 1997;388:78–82. doi: 10.1038/40418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechler T, Shevchenko A, Li R. Direct involvement of yeast type I myosins in Cdc42-dependent actin polymerization. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:363–374. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.2.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechler T, Jonsdottir GA, Klee SK, et al. A two-tiered mechanism by which Cdc42 controls the localization of an Arp213. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:261–270. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WL, Bezanilla M, Pollard TD. Fission yeast myosin-I, Myo1p, stimulates actin assembly by Arp2/3 complex and shares functions with WASp. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:789–800. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.4.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HP, Bretscher A. Disruption of the single tropomyosin gene in yeast results in the disappearance of actin cables from the cytoskeleton. Cell. 1989;57:233–242. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90961-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loisel TP, Boujemaa R, Pantaloni D, Carlier MF. Reconstitution of actin-based motility of Listeria and Shigella using pure proteins [see comments] Nature. 1999;401:613–616. doi: 10.1038/44183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung G, Remmert K, Wu X, Volosky JM, Hammer JA., III The Dictyostelium CARMIL protein links capping protein and the Arp2/3 complex to type I myosins through their SH3 domains. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1479–1497. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.7.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Cantley LC, Janmey PA, Kirschner MW. Corequirement of specific phosphoinositides and small GTP-binding protein Cdc42 in inducing actin assembly in Xenopus egg extracts. J Cell Biol. 1998a;140:1125–1136. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Rohatgi R, Kirschner MW. The Arp2/3 complex mediates actin polymerization induced by the small GTP-binding protein Cdc42. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998b;95:15362–15367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machesky LM, Mullins RD, Higgs HN, Kaiser DA, Blanchoin L, May RC, Hall ME, Pollard TD. Scar, a WASp-related protein, activates nucleation of actin filaments by the Arp2/3 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3739–3744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madania A, Dumoulin P, Grava S, Kitamoto H, Scharer-Brodbeck C, Soulard A, Moreau V, Winsor B. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologue of human Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein Las17p interacts with the Arp2/3 complex. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3521–3538. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.10.3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrifield CJ, Moss SE, Ballestrem C, Imhof BA, Giese G, Wunderlich I, Almers W. Endocytic vesicles move at the tips of actin tails in cultured mast cells. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:72–74. doi: 10.1038/9048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimuro H, Suzuki T, Suetsugu S, Miki H, Takenawa T, Sasakawa C. Profilin is required for sustaining efficient intra- and intercellular spreading of Shigella flexneri. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28893–28901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003882200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooseker MS, Cheney RE. Unconventional myosins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:633–675. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.003221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau V, Galan JM, Devilliers G, Haguenauer-Tsapis R, Winsor B. The yeast actin-related protein Arp2p is required for the internalization step of endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1361–1375. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.7.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland J, Preuss D, Moon A, Wong A, Drubin D, Botstein D. Ultrastructure of the yeast actin cytoskeleton and its association with the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:381–391. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.2.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus EM, Soldati T. A myosin I is involved in membrane recycling from early endosomes. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1013–1026. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak KD, Peterson MD, Reedy MC, Titus MA. Dictyostelium myosin I double mutants exhibit conditional defects in pinocytosis. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1205–1221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.5.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard TD, Blanchoin L, Mullins RD. Molecular mechanisms controlling actin filament dynamics in nonmuscle cells. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:545–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescianotto-Baschong C, Riezman H. Morphology of the yeast endocytic pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:173–189. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruyne D, Bretscher A. Polarization of cell growth in yeast. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:571–585. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riezman H, Munn A, Geli MI, Hicke L. Actin-, myosin- and ubiquitin-dependent endocytosis. Experientia. 1996;52:1033–1041. doi: 10.1007/BF01952099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatgi R, Ma L, Miki H, Lopez M, Kirchhausen T, Takenawa T, Kirschner MW. The interaction between N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex links Cdc42- dependent signals to actin assembly. Cell. 1999;97:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80732-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodal AA, Tetreault JW, Lappalainen P, Drubin DG, Amberg DC. Aip1p interacts with cofilin to disassemble actin filaments. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1251–1264. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.6.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt J, Agnew BJ, Abe H, Bamburg JR, Mitchison TJ. Xenopus actin depolymerizing factor/cofilin (XAC) is responsible for the turnover of actin filaments in Listeria monocytogenes tails. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:1323–1332. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagot I, Klee SK, Pellman D. Yeast formins regulate cell polarity by controlling the assembly of actin cables. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:42–50. doi: 10.1038/ncb719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schaerer-Brodbeck C, Riezman H. Functional interactions between the p35 subunit of the Arp2/3 complex and calmodulin in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:1113–1127. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.4.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman S, Fink G, Lawrence C. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Taunton J, Rowning BA, Coughlin ML, Wu M, Moon RT, Mitchison TJ, Larabell CA. Actin-dependent propulsion of endosomes and lysosomes by recruitment of N-WASP. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:519–530. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter D, Podtelejnikov AV, Mann M, Li R. The complex containing actin-related proteins Arp2 and Arp3 is required for the motility and integrity of yeast actin patches. Curr Biol. 1997;7:519–529. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00223-5. , R593 (errata). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter D, Lechler T, Li R. Activation of the yeast Arp2/3 complex by Bee1p, a WASP-family protein. Curr Biol. 1999a;9:501–504. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter D, Lechler T, Li R. Activation of the yeast Arp2/3 complex by Bee1p, a WASP-family protein. Curr Biol. 1999b;9:501–504. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter DC, Choe EY, Li R. Genetic dissection of the budding yeast Arp2/3 complex: a comparison of the in vivo and structural roles of individual subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999c;96:7288–7293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolven AK, Belmont LD, Mahoney NM, Almo SC, Drubin DG. In vivo importance of actin nucleotide exchange catalyzed by profilin. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:895–904. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.4.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita RA, May GS. Constitutive activation of endocytosis by mutation of myoA, the myosin I gene of Aspergillus nidulans. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14644–14648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarar D, To W, Abo A, Welch MD. The Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein directs actin-based motility by stimulating actin nucleation with the Arp2/3 complex. Curr Biol. 1999;9:555–558. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]