Abstract

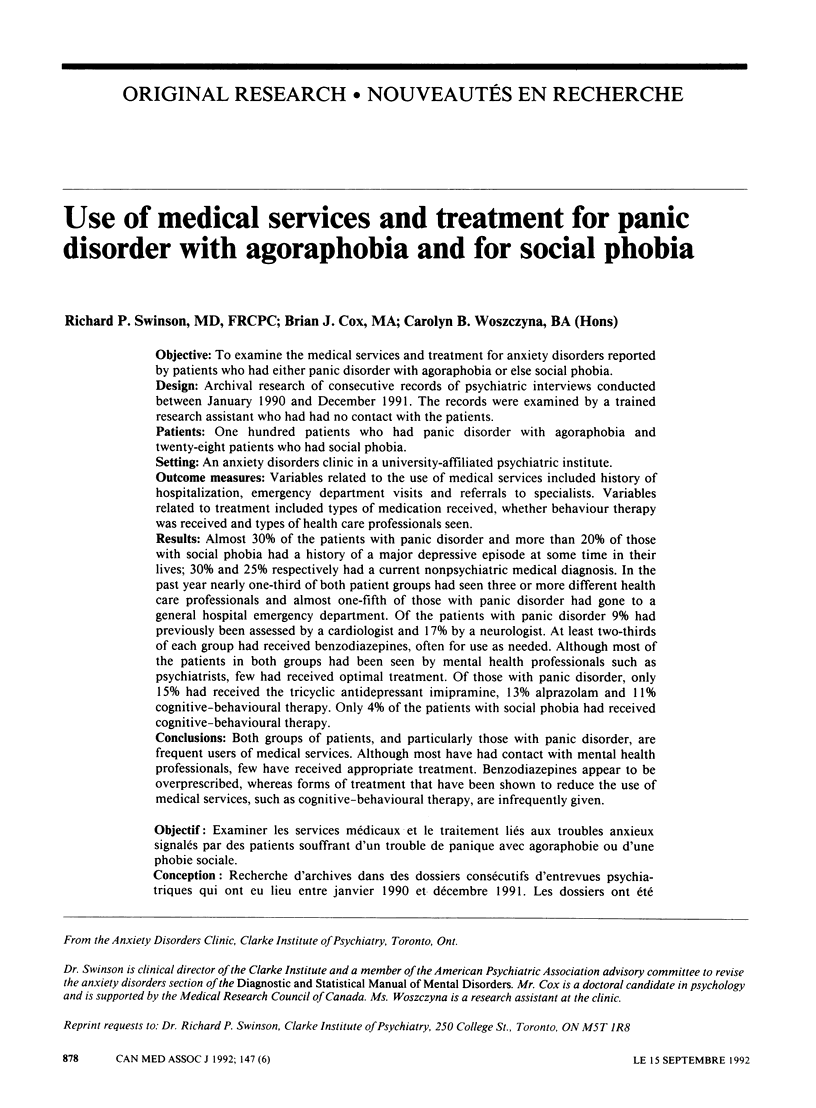

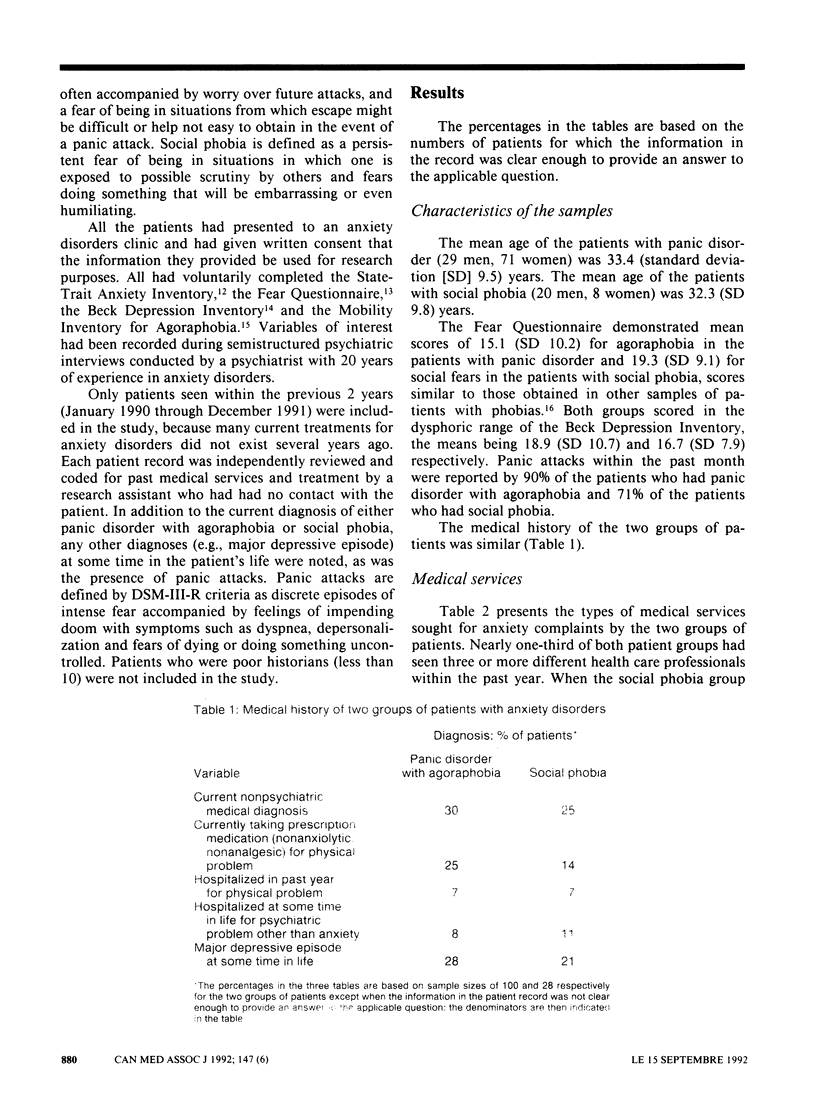

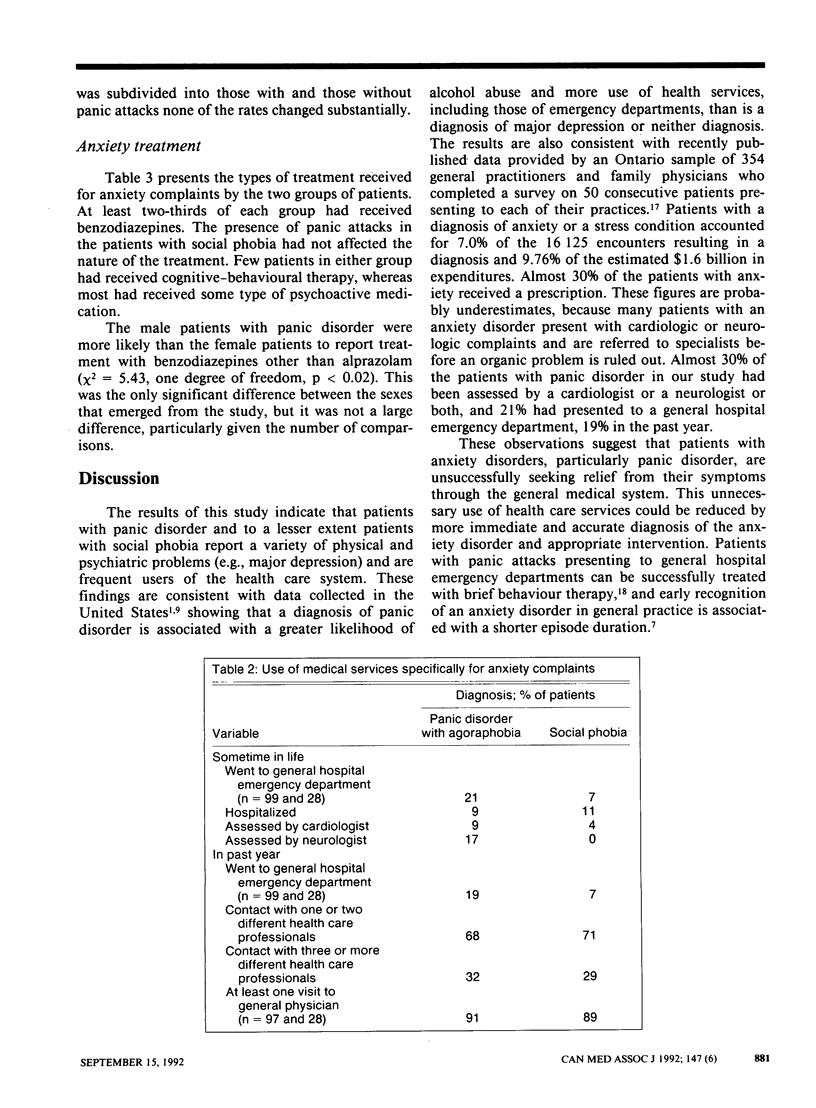

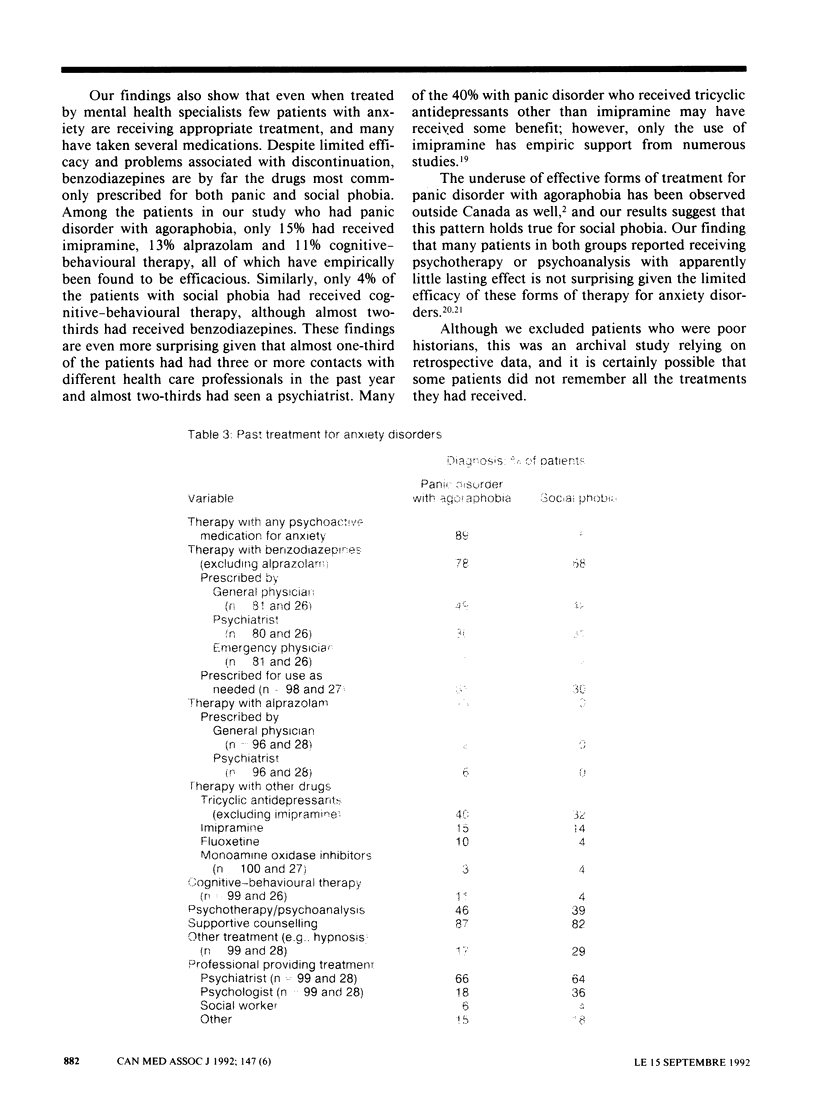

OBJECTIVE: To examine the medical services and treatment for anxiety disorders reported by patients who had either panic disorder with agoraphobia or else social phobia. DESIGN: Archival research of consecutive records of psychiatric interviews conducted between January 1990 and December 1991. The records were examined by a trained research assistant who had had no contact with the patients. PATIENTS: One hundred patients who had panic disorder with agoraphobia and twenty-eight patients who had social phobia. SETTING: An anxiety disorders clinic in a university-affiliated psychiatric institute. OUTCOME MEASURES: Variables related to the use of medical services included history of hospitalization, emergency department visits and referrals to specialists. Variables related to treatment included types of medication received, whether behaviour therapy was received and types of health care professionals seen. RESULTS: Almost 30% of the patients with panic disorder and more than 20% of those with social phobia had a history of a major depressive episode at some time in their lives; 30% and 25% respectively had a current nonpsychiatric medical diagnosis. In the past year nearly one-third of both patient groups had seen three or more different health care professionals and almost one-fifth of those with panic disorder had gone to a general hospital emergency department. Of the patients with panic disorder 9% had previously been assessed by a cardiologist and 17% by a neurologist. At least two-thirds of each group had received benzodiazepines, often for use as needed. Although most of the patients in both groups had been seen by mental health professionals such as psychiatrists, few had received optimal treatment. Of those with panic disorder, only 15% had received the tricyclic antidepressant imipramine, 13% alprazolam and 11% cognitive-behavioural therapy. Only 4% of the patients with social phobia had received cognitive-behavioural therapy. CONCLUSIONS: Both groups of patients, and particularly those with panic disorder, are frequent users of medical services. Although most have had contact with mental health professionals, few have received appropriate treatment. Benzodiazepines appear to be overprescribed, whereas forms of treatment that have been shown to reduce the use of medical services, such as cognitive-behavioural therapy, are infrequently given.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BECK A. T., WARD C. H., MENDELSON M., MOCK J., ERBAUGH J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961 Jun;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J. H. Use of mental health services for the treatment of panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1986 Dec;143(12):1569–1574. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.12.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless D. L., Caputo G. C., Jasin S. E., Gracely E. J., Williams C. The Mobility Inventory for Agoraphobia. Behav Res Ther. 1985;23(1):35–44. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(85)90140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava G. A., Kellner R., Zielezny M., Grandi S. Hypochondriacal fears and beliefs in agoraphobia. J Affect Disord. 1988 May-Jun;14(3):239–244. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg G., Marks I., Waters H. Cost-benefit analysis of a controlled trial of nurse therapy for neuroses in primary care. Psychol Med. 1984 Aug;14(3):683–690. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700015294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz J. S., Weissman M. M., Ouellette R., Lish J. D., Klerman G. L. Quality of life in panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989 Nov;46(11):984–992. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks I. M., Mathews A. M. Brief standard self-rating for phobic patients. Behav Res Ther. 1979;17(3):263–267. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes R., Reich J., Clancy J., O'Gorman T. W. Reduction in hypochondriasis with treatment of panic disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1986 Nov;149:631–635. doi: 10.1192/bjp.149.5.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J., Koeter M. W., van den Brink W., van de Willige G. Recognition, management, and course of anxiety and depression in general practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991 Aug;48(8):700–706. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810320024004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinson R. P., Cox B. J., Kerr S. A., Kuch K., Fergus K. D. A survey of anxiety disorders clinics in Canadian hospitals. Can J Psychiatry. 1992 Apr;37(3):188–191. doi: 10.1177/070674379203700308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinson R. P., Soulios C., Cox B. J., Kuch K. Brief treatment of emergency room patients with panic attacks. Am J Psychiatry. 1992 Jul;149(7):944–946. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.7.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C. B., King R., Margraf J., Ehlers A., Telch M., Roth W. T., Agras W. S. Use of medication and in vivo exposure in volunteers for panic disorder research. Am J Psychiatry. 1989 Nov;146(11):1423–1426. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.11.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman M. M., Klerman G. L., Markowitz J. S., Ouellette R. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in panic disorder and attacks. N Engl J Med. 1989 Nov 2;321(18):1209–1214. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911023211801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]