Abstract

Viruses often contain cis-acting RNA elements, which facilitate the posttranscriptional processing and export of their messages. These elements fall into two classes distinguished by the presence of either viral or cellular RNA binding proteins. To date, studies have indicated that the viral proteins utilize the CRM1-dependent export pathway, while the cellular factors generally function in a CRM1-independent manner. The cis-acting element found in the woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) (the WHV posttranscriptional regulatory element [WPRE]) has the ability to posttranscriptionally stimulate transgene expression and requires no viral proteins to function. Conventional wisdom suggests that the WPRE would function in a CRM1-independent manner. However, our studies on this element reveal that its efficient function is sensitive to the overexpression of the C terminus of CAN/Nup214 and treatment with the antimicrobial agent leptomycin B. Furthermore, the overexpression of CRM1 stimulates WPRE activity. These results suggest a direct role for CRM1 in the export function of the WPRE. This observation suggests that the WPRE is directing messages into a CRM1-dependent mRNA export pathway in somatic mammalian cells.

The generation of mature cytoplasmic mRNAs requires numerous processing steps, namely, transcription, capping, splicing, polyadenylation, and transport to the cytoplasm. This process is tightly regulated, since aberrant transcripts are degraded in the nucleus and only properly processed mRNAs are exported to cytoplasm (43). Thus, nuclear export ensures that only completely processed mRNAs can be translated into protein.

Much of our present understanding of nuclear export has come from the study of how viruses exploit host cell RNA processing and export pathways. The first viral export system studies were those of complex retroviruses, exemplified by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). HIV-1 replication requires unspliced and partially spliced RNAs to be exported from the nucleus by the virally encoded Rev protein (9, 13, 44). Rev contains an RNA binding domain, which specifically binds to the Rev response element (RRE), located within the second intron of HIV-1 pre-mRNA, and a nuclear export signal (NES) that interacts with CRM1, a member of the importin β family of transport receptors (6, 15, 17, 44, 58).

The interaction between Rev and CRM1 is dependent upon CRM1 association with the GTP-bound form of the GTPase Ran protein (RanGTP). Once assembled, the RRE/Rev-CRM1-RanGTP ribonucleoprotein complex interacts with NPs, which trigger its nuclear export. CRM1 has been proposed to mediate this interaction by directly contacting selected nucleoporins (NPs), including CAN/Nup214. Binding of CRM1 to CAN has been mapped to the NP domain located within the extreme carboxy terminus of CAN (16). Overexpression of the isolated NP domain of CAN, termed ΔCAN, is able to inhibit Rev-mediated export by competing with the NPs for binding to CRM1 (2). Rev-mediated export is also inhibited by the antibiotic leptomycin B (LMB), which disrupts the interaction between NES and CRM1 (38, 39).

The use of the CRM1 export pathway is common among complex viruses. Other lentiviruses, such as feline immunodeficiency virus and equine infectious anemia virus, encode Rev-like proteins with atypical NESs that can interact with CRM1 (48, 51, 52). Complex oncoretroviruses, for instance, human T-cell leukemia virus and bovine leukemia virus, encode Rex proteins that are believed to use the CRM1 pathway (12, 23, 49). DNA viruses also utilize the CRM1 pathway. Thus, Epstein-Barr and herpes simplex viruses encode the MTA and ICP27 proteins, respectively, which use CRM1 to mediate the export of at least some of the virally encoded messages (45, 54, 56, 57). Additionally, influenza virus A uses the NS2 protein to mediate the export of viral messages via the CRM1 pathway (46, 47). Therefore, the use of virally encoded proteins to couple the export of viral RNA to the CRM1 pathway is a common strategy among the complex retroviruses. In contrast, simple viruses that use cellular RNA binding proteins for nuclear export do not use CRM1. The best characterized are the type D retroviruses. These simple retroviruses, exemplified by the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus, do not encode a Rev-like protein but rather act through a cis-acting RNA element named the constitutive transport element (CTE) (10, 11). Cytoplasmic accumulation of unspliced RNAs from these viruses involves the interaction between their CTEs and the host-encoded RNA binding protein Tap. Tap has been reported to directly bind the CTE and mediate the export of CTE-containing substrates (3, 21, 34). Although CTE and RRE/Rev can functionally substitute for each other in mediating nuclear RNA export, ΔCAN and LMB do not inhibit CTE-mediated nuclear export (2, 48). These data indicate that the Tap export mechanism is distinct from that of Rev and that it is CRM1 independent. Recent data indicated that Tap itself is a nuclear transport factor that directly mediates the nuclear export of its substrate RNA (3, 32, 59). Like CRM1, Tap interacts with CAN/Nup214, albeit through a distinct interaction domain (1, 32, 34). These data suggest that there are at least two independent mRNA export pathways: (i) a CRM1-dependent pathway utilized by virally encoded RNA binding proteins and (ii) a CRM1-independent pathway utilized by cellular factors.

Recently, Tap has also been implicated in the export of spliced cellular mRNAs (3, 34, 50, 55). However, in this case, the interaction between Tap and the cellular spliced messages appears to be mediated via the RNA binding proteins Aly (also known as Ref) and Y14 (60, 62, 65). These proteins are components of the recently identified exon junction complex, which is left associated with the exon-exon junction after the intron is excised (5, 40).

In contrast to the above examples, human hepatitis B virus (HBV) and woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) encode intronless messages. HBV and WHV messages contain specific cis-acting elements named posttranscriptional regulatory elements (PREs) (the HBV PRE [HPRE] and the WHV PRE [WPRE], respectively) that are essential for their expression (8, 27, 30). The activity of the PREs is independent of any virally encoded protein, suggesting that the PREs require as yet unidentified cellular trans-acting factors for function. Although the function of the PREs is unclear, their ability to work in a Rev-dependent assay and their requirement for RNA cytoplasmic accumulation have been suggestive of a role in export. Earlier experiments demonstrated that HPRE function is LMB resistant, indicating that, similar to CTE, it does not use CRM1 as an export receptor (48, 64). Mapping studies have demonstrated that HPRE and WPRE contain two homologous cis-acting sequences, or subelements, designated PREα and PREβ (7, 8). However, there are significant functional differences between HPRE and WPRE. In a Rev-dependent assay, WPRE is significantly more active than HPRE (8). WPRE also has the unique ability to posttranscriptionally stimulate the expression of heterologous cDNAs (41, 66). The increased activity correlates with the presence of an additional subelement, PREγ, which is not found in HPRE (8). The data suggest that WPRE, compared to HPRE, has an additional posttranscriptional activity that may shed light upon the mechanism by which intronless mRNAs are processed and exported from the nucleus.

In this study we demonstrated that WPRE posttranscriptional activity is both CRM1 dependent and independent. A potential for cooperation between CRM-dependent and -independent posttranscriptional activities is demonstrated by the observed cooperation between CRM1-dependent Rev and the CRM1-independent HPREβ subelement. Hence, WPRE is the first example of an RNA element that is partially dependent upon CRM1 function, does not require virally encoded proteins for its cytoplasmic localization, and has an activity that is mediated by several alternative pathways that may not be mutually exclusive but may instead be cooperative.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

The following plasmids were previously described: the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter plasmids pDM138 and pDM138RRE (23, 24); the pDM138 derivatives pDM138HPRE, pDM138WPRE, p138HPREβ, p138HPREβ(AS), p138Bul, and p138BulII (28) (7); and the ΔHBVPRE surface expression vector (ΔRV) (30) and its derivatives, ΔRVHPRE and ΔRVWPRE (8). To generate p138HPREβ/Bul and p138HPREβ(AS)/Bul, a fragment encompassing amino acids 1352 to 1684 of HBV, containing the HPREβ subelement (7), was inserted in both orientations into the ClaI site located at the 5′ end of the Bul fragment in pDM138Bul. To generate p138HPREβ/Bul(AS) and p138HPREβ(AS)/Bul(AS), the Bul fragment was inserted into the unique ClaI site located at the 3′ ends of the HPREβ subelements within p138HPREβ and p138HPREβ(AS). Rev was expressed from the plasmid pRSV-Rev (24) or ptk-Rev (26). The plasmid pBC12-ΔCAN, expressing amino acids 1864 to 2090 of CAN/Nup214 (2), was a gift from Bryan Cullen (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Duke University Medical Center). The plasmid pDMCRM1, expressing human CRM1, was kindly provided by David McDonald (Dept. of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Illinois at Chicago).

Cells lines and transient transfections.

The human and monkey kidney fibroblast cell lines, 293 and CV-1, respectively, were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and grown at 37°C. Approximately 24 h prior to transfection, 10-cm-diameter plates of confluent cells were split 1:60 into 6-well plates, for CAT or HBV surface antigen (HSAg) assay, and 1:10 into 15-cm-diameter plates, for Northern blot analysis. Transient transfections were performed using the calcium phosphate method (7). For CAT assays, cells were transfected with 0.25 μg of either pDM138 reporter constructs or 0.25 μg of pDM138RRE plus 0.25 μg of pRSV-Rev. ΔCAN inhibition experiments were performed with 0.5 μg of pBC12-ΔCAN. ΔCAN, CRM1, and Rev dose-response experiments were performed in the presence of increasing levels of the pBC12-ΔCAN (0 to 0.5 μg), pDMCRM1 (0 to 4 μg), or ptk-Rev (0 to 0.4 μg) expression plasmid. For CRM1 dose response, cells were transfected with 0.125 μg of pDM138WPRE. Each transfection included 0.25 μg of pCH110 (a simian virus 40 β-galactosidase [β-gal] reporter) and enough pUC118 or pCMVpoly(A) plasmid to bring the total amount of DNA to 2 μg. For the HSAg assay, cells were transfected with 0.25 μg of a ΔRV reporter construct and 0.25 μg of a plasmid coding for a secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP). The total amount of DNA was kept constant (2 μg) with the pCMVpoly(A) plasmid. All transfections were performed in triplicate, and data were normalized to the cotransfected internal controls (β-gal for the CAT assay and SEAP for the HSAg assay). For Northern blot analysis, cells in 15-cm-diameter plates were transfected with 4.5 μg of pDM138 constructs or 4.5 μg of pDM138RRE plus 4.5 μg of pRSV-Rev and 4.5 μg of pCH110. For CRM1 treatment, 2.25 μg of pDM138WPRE was used. Total transfected DNA was kept constant (30 μg) with the pUC118 or pCMVpoly(A) plasmids. LMB treatment was performed as previously described (48). Briefly, 18 h posttransfection, culture medium was replaced with fresh medium with or without 5 nM LMB. Cells were harvested for analysis 24 h later. No cell death was observed at the end of the 24 h LMB treatment. The CAT and HSAg assays have been described elsewhere (7, 8).

Northern blot analysis of RNA.

Cells from the 293 cell line were harvested using phosphate-buffered saline containing 5 mM EDTA, followed by a brief centrifugation. Nuclear and cytoplasmic RNAs were prepared as previously described (8), except that the cytoplasmic lysis buffer consisted of 0.01 M Tris (pH 8.00), 0.14 M NaCl, 0.0015 M MgCl2, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and 20% glycerol. Cytoplasmic and nuclear poly(A)+ RNA selection was accomplished by using the Poly(A) Pure kit from Ambion according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Ten micrograms of cytoplasmic and 5 μg of nuclear poly(A)+ RNA were electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels containing 20 mM guanidine thiocyanate (20) and transferred to a Duralon-UV membrane (Stratagene). The 5′ LTR probe was obtained by digesting pDM138 with XbaI and NotI. This probe hybridizes with unspliced pDM138 RNA. The β-gal probe was obtained by digesting pCH110 with SacI and EcoRV. Radiolabeling of the probes with [α-32P]dCTP was performed by using the Prime-It kit from Stratagene. Blots were hybridized with the probes in UltraHyb (Ambion), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitation of the cytoplasmic accumulation of the unspliced and β-gal mRNAs was performed using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager. To correct for different transfection efficiencies, the data for the unspliced mRNAs were normalized to the β-gal values.

Numbering of sequences.

The sequence numbering presented in this report is based on the following GenBank sequences: D003329 for HBV, J02442 for WHV, and K03455 for HIV-1.

RESULTS

ΔCAN and LMB inhibit WPRE-mediated export.

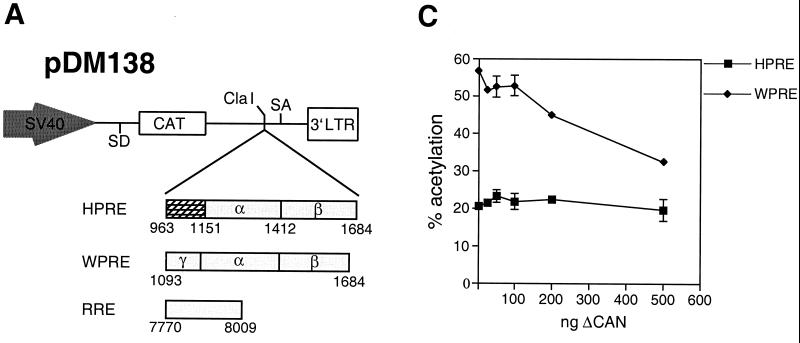

To test whether the functional difference between HPRE and WPRE was CRM1-dependent, we used the dominant negative form of CAN/Nup214 (ΔCAN), which was shown to specifically inhibit CRM1 (2). We hypothesized that, if WPRE function is mediated by CRM1, then the cytoplasmic accumulation of WPRE-containing RNA should be inhibited by overexpression of ΔCAN. For this study we utilized the well-characterized pDM138 system. We have previously shown that the PREs could substitute for RRE/Rev in facilitating the export of unspliced pDM138 transcripts (7). A schematic representation of the pDM138 reporter and the constructs utilized in this study is presented in Fig. 1A. The reporter is derived from the second half of the HIV-1 sequence, with the CAT gene placed within the intron (24). In the absence of any export element, the CAT coding region is removed by splicing and degraded in the nucleus. Insertion of a functional transport element into the unique ClaI site results in cytoplasmic accumulation of unspliced reporter, allowing the CAT gene to be translated. Thus, CAT assay can be used to quantitate export activity of the element of interest. Human 293 cells were transfected with pDM138WPRE in the presence or absence of 0.5 μg of pBC12ΔCAN, a concentration reported to be efficient in inhibiting Rev-mediated export (2). To demonstrate specificity for the observed effects, we used pDM138RRE/Rev as a positive control. As shown in Fig. 1B, overexpression of ΔCAN disrupted Rev function, without perturbing the function of HPRE. In the absence of ΔCAN, WPRE was 2.7 times more active than HPRE. Interestingly, ΔCAN inhibited WPRE activity by 57%, to approximately the same level of activity as the HPRE. CTE RNA, the negative control, was not affected, which is consistent with previous results demonstrating that the CTE does not depend on a leucine-rich NES for its function (2, 48) (data not shown). The inhibition of WPRE function was specific, as demonstrated by a dose-response experiment, while increased concentrations of ΔCAN had no effect on HPRE activity (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

ΔCAN inhibits WPRE function. (A) Schematic representation of the pDM138 reporter and constructs utilized in Fig. 1B and C. The pDM138 reporter is derived from the second intron of the HIV-1 genome. The CAT gene, located within the intron, is expressed only when unspliced RNA is exported. The unique ClaI restriction site, splice donor (SD), splice acceptor (SA), and 3′ LTR are indicated. HPRE contains a region of the HBV liver-specific enhancer I (hatched box) that is not required for its function. (B) ΔCAN inhibits WPRE-dependent CAT expression. 293 cells were transiently transfected with the indicated expression plasmids in the presence or absence of ΔCAN. β-gal expression vector was included for transfection efficiency normalization. Results shown are the means ± standard deviations (SD) of triplicate CAT values. (C) Dose-response curves of ΔCAN effects on WPRE- and HPRE-mediated CAT expression. 293 cells were transiently transfected with WPRE- and HPRE-containing pDM138 reporter, in the presence of increasing concentrations of ΔCAN. Normalized CAT values shown are the means ± SD of triplicate transfections.

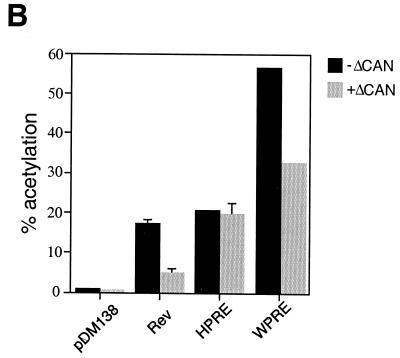

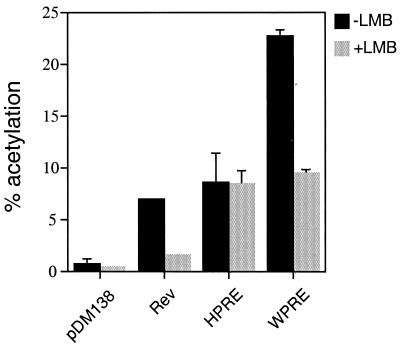

To test whether ΔCAN could also inhibit WPRE activity in the more natural context of the intronless surface mRNA, we used the HSAg assay. This assay uses an intronless HSAg expression vector (ΔR5) from which the HPRE has been removed (30). Insertion of any of the PREs into the unique ClaI site contained within the intronless HSAg message results in efficient HBV surface gene expression that can be quantified in the culture medium by radioimmunoassay (8). The WPRE and HPRE surface constructs depicted in Fig. 2A were transiently transfected into 293 cells. As previously reported, WPRE-mediated surface protein expression was slightly higher than that mediated by HPRE (8). Similar to data obtained with the pDM138 reporter assay, overexpression of ΔCAN did not inhibit HPRE-mediated surface antigen expression (Fig. 2B). However, WPRE-mediated surface expression was inhibited about 30%, to approximately the same level as HPRE-mediated expression (Fig. 2B). These results demonstrate that ΔCAN can partially inhibit WPRE activity in a specific, dose-response fashion.

FIG. 2.

ΔCAN inhibits WPRE-mediated HSAg expression. (A) Schematic representation of the constructs used in the surface antigen assay. The surface antigen gene is expressed only when WPRE or HPRE are inserted into the unique ClaI site contained within the intronless message. ΔRV, the HSAg expression vector. (B) WPRE-dependent HSAg expression is inhibited by ΔCAN. 293 cells were transiently transfected with the indicated surface constructs in the presence or absence of ΔCAN. A SEAP-encoding expression plasmid was included as an internal control for the efficiency of transfection. SEAP-normalized count-per-minute values are the means ± SD from the media of triplicate transfections.

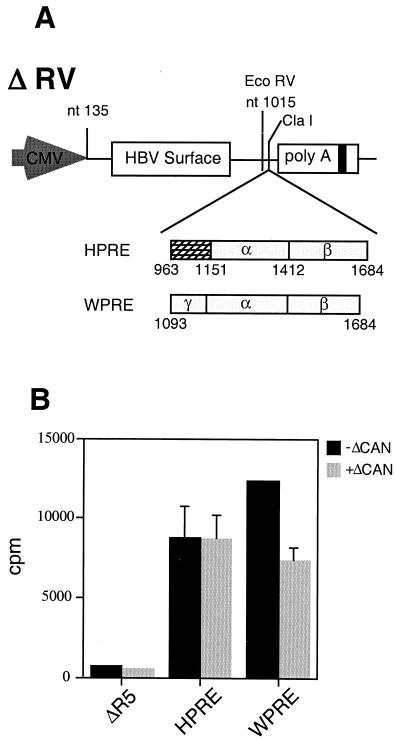

The above data suggested that a part of the WPRE activity may be CRM1 dependent. As previously discussed, LMB specifically disrupts the interaction between CRM1 and NES-bearing proteins. To test whether WPRE activity is LMB sensitive, cells transfected with pDM138HPRE, pDM138WPRE, and pDM138RRE+Rev were treated with LMB for 24 h. Rev, the positive control, was inhibited over 80% by LMB, while HPRE, the negative control, was unaffected (Fig. 3). Interestingly, LMB inhibited WPRE activity by approximately 50%, to the level of HPRE activity. These results suggest that WPRE posttranscriptional function is both CRM1 dependent and independent, while the less active HPRE is entirely CRM1 independent. Moreover, the data indicate that the increased WPRE activity was due to this additional CRM1 dependency.

FIG. 3.

LMB inhibits WPRE-mediated CAT expression. 293 cells were transiently transfected in triplicate with the constructs described in Fig. 1A. A β-gal expression vector was included for transfection efficiency normalization. Transfections were performed in the presence or absence of LMB. Results shown are the means ± SD of triplicate CAT values.

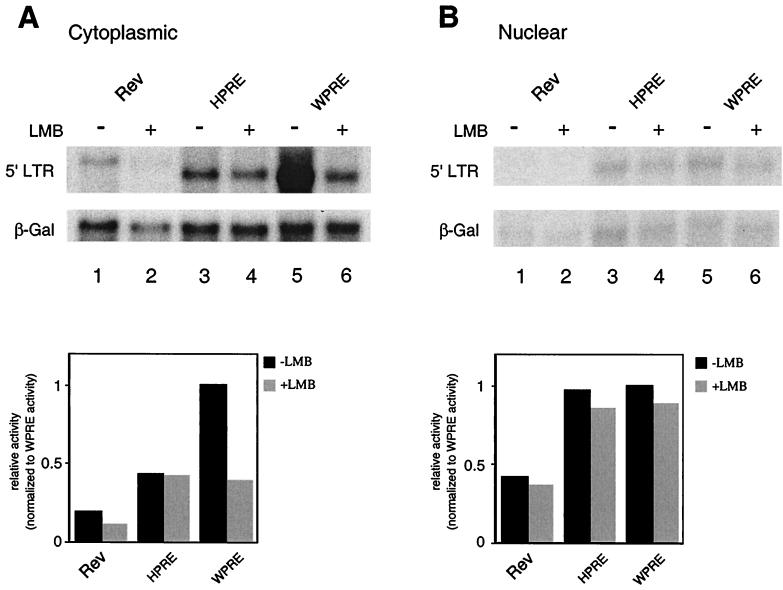

Reduced CAT activity is due to inhibition of unspliced CAT RNA export.

Since the CAT assays represent an indirect measure of cytoplasmic unspliced RNA levels, we also performed a Northern blot analysis for unspliced CAT RNA (Fig. 4). Cytoplasmic and nuclear poly(A)+ RNAs (Figs. 4A and B, respectively) were isolated from LMB-treated and untreated 293 cells transfected with pDM138WPRE, pDM138RRE/pRSV−Rev, and pDM138HPRE. PhosphorImager quantitation of the Northern blot is shown underneath each blot. Consistent with the CAT and HSAg assays, LMB treatment inhibited Rev-mediated export, while HPRE-mediated cytoplasmic accumulation was unaffected. Direct RNA analysis of cytoplasmic accumulation of WPRE-containing RNA found that LMB inhibited WPRE activity by ∼50%, to levels similar to those observed for HPRE. These data confirm that WPRE-mediated accumulation of cytoplasmic RNA is partially dependent upon CRM1 function. The data also demonstrate that WPRE is not dedicated to an exclusive posttranscriptional processing pathway, but is instead a potential example of CRM1-dependent and -independent posttranscriptional processing events being mediated by a single RNA element.

FIG. 4.

LMB inhibition of WPRE-mediated CAT expression occurs at the level of RNA export. Northern blot analysis of cytoplasmic (A) and nuclear (B) poly(A)+ RNAs isolated from 293 cells transiently transfected with the indicated constructs in the presence or absence of LMB is shown. Blots were hybridized with probes complementary to HIV 5′ LTR or β-gal coding sequences. PhosphorImager quantification is shown underneath each blot. Values were normalized to the amount of poly(A)+ β-gal RNA and presented as activities relative to WPRE activity.

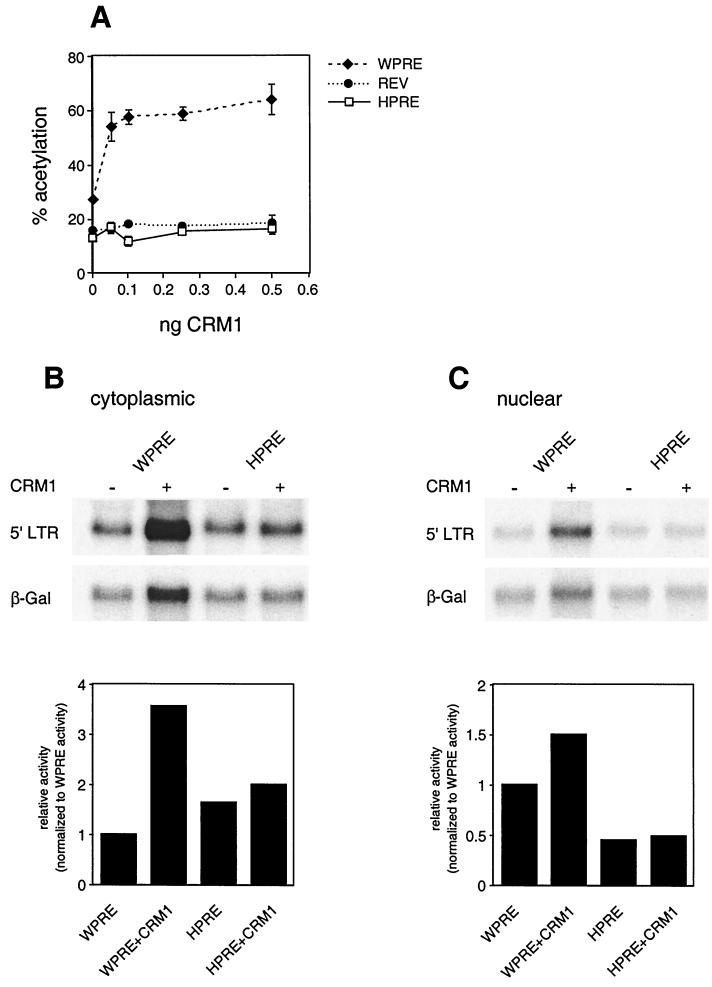

Overexpression of CRM1 stimulates WPRE-mediated export.

The ability of LMB and ΔCAN to inhibit WPRE function suggests that CRM1 is required for the maximal activity of this element. To further explore this relationship, we determined the effect of CRM1 overexpression on the function of WPRE (Fig. 5). For this study, constant amounts of DNA encoding the reporters for the WPRE, HPRE, and RRE were cotransfected with increasing amounts of a CRM1 expression vector. To facilitate comparison, half as much of the WPRE reporter was transfected. The results of this study revealed that the activity of the WPRE was stimulated by the exogenous expression of CRM1, while the activity of RRE/Rev and HPRE did not change significantly (Fig. 5A). Cotransfection of larger amounts of the CRM1 expression vector did not have any additional stimulatory effect on any of the reporters. To explore the observation further, cytoplasmic (Fig. 5B) and nuclear (Fig. 5C) poly(A)+ RNAs were isolated from 293 cells transfected with either the WPRE or HPRE in the presence or absence of exogenous CRM1 and analyzed by Northern blot analysis. Again, half as much of pDM138WPRE relative to pDM138HPRE was transfected. Quantitation of the Northern blot analysis results, normalized to the β-gal internal control, is shown below each blot. The RNA analysis revealed that the CRM1-mediated increase in levels of WPRE-stimulated expression was reflected by a corresponding increase in the cytoplasmic RNA levels. Importantly, the coexpression of CRM1 caused an increase in the ratio of cytoplasmic to nuclear RNA. Cytoplasmic WPRE RNA was increased by more than threefold, while the nuclear fraction increased by 50%. The increase in the amount of cytoplasmic WPRE RNA relative to the increase in the nuclear fraction when CRM1 is overexpressed is consistent with a stimulation of the rate of nuclear export of the WPRE-containing messages. In contrast, the levels of HPRE-containing messages are not altered by the overexpression of CRM1.

FIG. 5.

CRM1 overexpression stimulates WPRE-mediated export. (A) Effect of increasing concentrations of CRM1 on WPRE- and HPRE-mediated CAT expression. 293 cells were transiently transfected with 0.125 μg of pDM138WPRE or 0.25 μg of pDM138HPRE reporters, in the presence of increasing concentrations of pDMCRM1. Normalized CAT values shown are the means ± SD of triplicate transfections. (B and C) Northern blot analysis of cytoplasmic (B) and nuclear (C) poly(A)+ RNAs isolated from 293 cells transiently transfected with the indicated constructs in the presence or absence of 1 μg of CRM1. Blots were hybridized with probes complementary to HIV 5′ LTR or β-gal coding sequences. PhosphorImager quantification is shown below each blot. Values were normalized to the amount of poly(A)+ β-gal RNA and represent activities relative to WPRE activity.

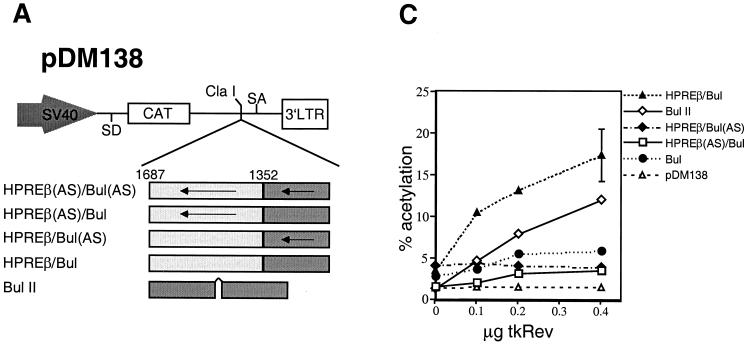

CRM1-dependent and -independent transport elements can act cooperatively.

Our results demonstrated that WPRE function was partially CRM1 dependent, which suggests that the CRM1-dependent element(s) of WPRE was able to function in concert with the CRM1-independent element(s) to stimulate the cytoplasmic accumulation of unspliced messages. To test whether CRM1-independent and -dependent subelements could function together, we generated a chimeric export element containing a minimal Rev binding site and HPREβ. Previously, we have shown that HPREβ is CRM1-independent, functionally conserved, and interchangeable between HPRE and WPRE (8). For the Rev binding site, we utilized the previously characterized derivative known as Bul. Bul is composed of the RRE high-affinity binding site for Rev, placed on a double-stranded RNA pedestal (28).

This artificial element is relatively inactive by itself (28). However, duplication of the site generates an element with wild-type activity (28). Thus, the duplication of the high-affinity site mimics the function of the respective native response element (RRE), which contains both a high-affinity and several low-affinity binding sites (6, 37, 63). Our chimera, pDM138HPREβ-Bul, consisted of HPREβ (CRM1 independent) adjacent to Bul (CRM1 dependent). Three control reporters were also generated: both subelements in the antisense (AS) orientation, pDM138HPREβ(AS)-Bul(AS), or only one subelement in the AS orientation, pDM138HPREβ(AS)-Bul or pDM138HPREβ-Bul(AS). The different reporter derivatives used in this experiment are schematically shown in Fig. 6A. The positive control consisted of pDM138Bul II, which contains two copies of the Bul element (28). These reporter constructs were transfected into CV-1 cells in the presence or absence of saturating amounts of Rev (25). The results are presented in Fig. 6B. The negative control, pDM138HPREβ(AS)-Bul(AS), was not activated in the presence of Rev. Rev trans-activated pDM138HPREβ(AS)-Bul to 20% of the level of the positive control, consistent with the construct containing only one copy of Bul. Due to the presence of HPREβ, the construct pDM138HPREβ-Bul(AS) exhibited a low level of activity (20% of the positive control) which was Rev-independent. This result was expected for the following reasons: (i) HPRE does not need Rev to function (48, 64), and (ii) HPRE subelements function cooperatively; therefore, the presence of only one subelement results in minimal activity (7). When Rev was cotransfected with pDM138HPREβ-Bul, the level of activation was 86% of that of the positive control with Rev. These results demonstrated that combining HPREβ and Bul can stimulate the pDM138 reporter to levels greater than those resulting from the sum of their individual activities.

FIG. 6.

CRM1-dependent and CRM1-independent transport elements act cooperatively to mediate the export of unspliced RNA. (A) Schematic representation of the pDM138 and constructs used in Fig. 5B and C. The arrows indicate the AS orientation of the HPREβ and Bul subelements. (B) HPREβ and Bul act synergistically to stimulate CAT expression from the pDM138 reporter. CV-1 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and a β-gal expression plasmid, in the presence or absence of Rev. β-Gal values were used for transfection efficiency normalization. Results shown are the means ± SD of triplicate CAT values. (C) Dose-response analysis of Rev effect on chimera-mediated CAT expression. 293 cells were transfected with the constructs shown in Fig. 5A in the presence of increasing concentrations of Rev. Normalized CAT values shown are the means ± SD of triplicate transfections.

To further explore the observed Rev-dependent effect, we performed a dose-response experiment using nonsaturating levels of Rev expressed from the plasmid ptk-Rev. We have previously shown that expression of Rev from the minimal HSV-TK promoter results in CAT activity proportional to the amount of plasmid transfected (25). Increasing amounts of ptk-Rev were cotransfected into 293 cells together with pDM138 or pDM138 constructs containing HPREβ/Bul, HPREβ(AS)/Bul, HPREβ/Bul(AS), Bul, and Bul II. The results are presented in Fig. 6C. Regardless of the amount transfected, Rev did not have any effect on pDM138. CAT expression from pDM138HPREβ(AS)-Bul, which contains a single binding site for Rev, was slightly affected by increasing amounts of Rev. In contrast, increasing concentrations of Rev increased CAT expression from both pDM138HPREβ-Bul and pDM138BullII in proportion to the amount of trans-activator present; note that pDM138BullII activity was lower that that of pDM138HPREβ-Bul (compare Fig. 6B to Fig. 6C). This might be due to the fact that different cell lines were used for the two experiments (see figure legend). For each concentration point, pDM138HPREβ-Bul showed greater than additive activity compared to those of pDM138HPREβ(AS)-Bul and pDM138HPREβ-Bul(AS). Therefore, the synergy achieved by combining Rev/Bul with HPREβ was not dependent on the Rev concentration or the identity of the cell line. Further analysis of Rev mutants showed that all three functional domains of HIV-1 Rev were required. Mutations in the NES, RNA binding domain, and multimerization domains prevented any stimulation of pDM138HPREβ-Bul (data not shown). Since a functional NES was required, it suggests that the synergy observed was dependent on the cooperation between CRM1 and the cellular factor(s) that mediate HPREβ function.

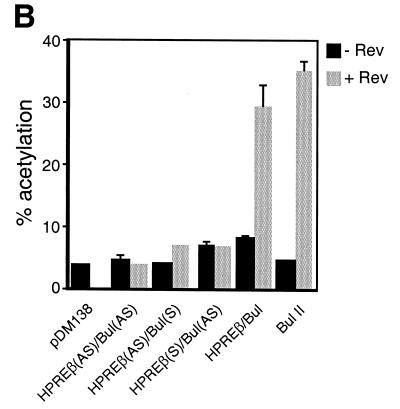

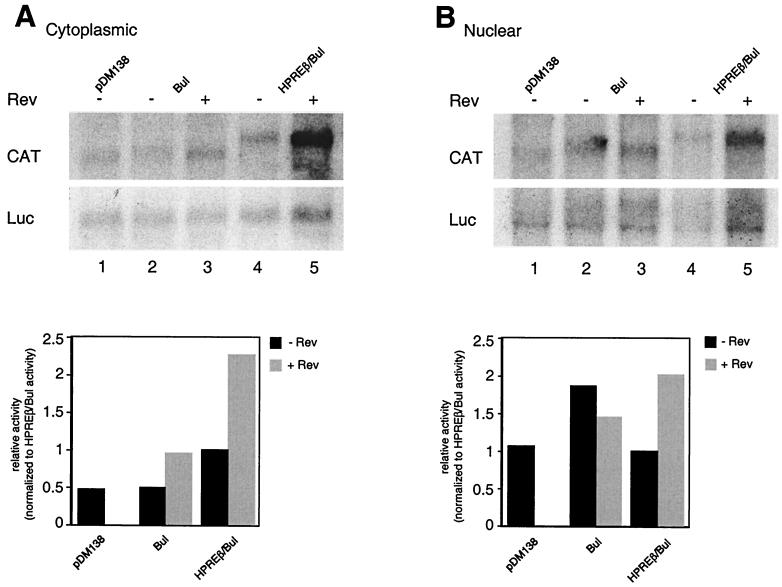

To confirm that the observed synergistic activation of pDM138 was the consequence of an increased accumulation of unspliced CAT-containing RNA, we performed a Northern blot analysis. Cytoplasmic (Fig. 7A) and nuclear (Fig. 7B) poly(A)+ RNAs were isolated from 293 cells transfected with pDM138, pDM138HPREβ-Bul, pDM138HPREβ, and pDM138Bul. Blots were probed for CAT (upper panels) and luciferase (lower panels). PhosphorImager data are shown under each blot. In the absence of Rev, the amount of exported pDM138Bul was the same as that of pDM138, as expected. In the presence of Rev, the amount of cytoplasmic pDM138Bul was increased slightly. In the absence of Rev, the chimeric element accumulated unspliced RNA in the cytoplasm slightly more than pDM138. This is consistent with the low level of activity previously reported for the HPREβ subelement in CAT assays (7). In the presence of Rev, the export activity of the chimeric element was higher than those of the other constructs.

FIG. 7.

Synergistic stimulation of CAT expression by HPREβ/Bul chimera is due to an increased nuclear export of unspliced RNA. Northern blot analysis was performed on cytoplasmic (A) and nuclear (B) poly(A)+ RNAs isolated from 293 cells transiently transfected with the indicated constructs in the presence or absence of Rev. Blots were hybridized with probes complementary to CAT or luciferase coding sequences. PhosphorImager quantification of the effect of Rev on chimera-mediated RNA export is presented below each blot. Values were normalized to the amount of poly(A)+ luciferase RNA and show activities relative to HPREβ/Bul activity.

Taken together, these data demonstrated that CRM1-dependent and -independent export mechanisms can cooperate to enhance the cytoplasmic accumulation of a single mRNA.

DISCUSSION

Originally it was believed that Rev/CRM1-mediated export likely represented the paradigm for all cellular RNA export pathways. However, studies with LMB and the discovery that simpler retroviruses use cellular factors other than CRM1 to export their unspliced mRNA (1, 21, 31, 32, 33, 53) made the role of CRM1 in cellular mRNA export debatable (61). This led to a general belief that CRM1 directs RNA export only when virally encoded RNA binding proteins act as adapters, whereas cellular factor-dependent RNA export, i.e., CTE RNA or cellular mRNA, is CRM1 independent (2, 14, 15). Recently, it has been demonstrated that, in specific circumstances, the export of certain cellular mRNAs can be CRM1 dependent (4). The studies by Gallouzi and coworkers found that the c-fos message can be exported in a CRM1-dependent manner after heat shock (18, 19). We decided to further investigate this controversial issue by using WPRE RNA as a model system. Consistent with the study of c-fos mRNA export, we show that CRM1 is involved in an mRNA export pathway that is not mediated by virally encoded NES-containing proteins.

ΔCAN overexpression can inhibit WPRE activity, but not HPRE activity, in both CAT and HSAg assays (Fig. 1 and 2). The inhibition of WPRE by ΔCAN suggests that part of the WPRE activity requires functional CRM1. However, recent data have implied that ΔCAN is not a selective inhibitor of CRM1 function (22). A fusion between Tap and an export-incompetent Rev mutant protein (RevM10) was LMB insensitive, indicating that it does not use the CRM1-mediated export pathway. However, ΔCAN was able to inhibit RevM10-Tap-mediated export. It is not clear why ΔCAN affects RevM10-Tap. Even though the C terminus of Tap has been shown to bind the FG repeat domain of CAN/Nup214 in vitro, effective binding by Tap requires a higher number of repeats (residues 1690 to 2090) than the number of repeats present in ΔCAN (1, 34). Additionally, in vivo experiments demonstrated that Tap-mediated CTE and cellular mRNA export is not sensitive to ΔCAN (2). A conformational change in RevM10-Tap could render this fusion protein sensitive to ΔCAN, while the native Tap protein is insensitive. This could explain the ability of ΔCAN to act as a selective inhibitor of CRM1 function. Moreover, if export function is LMB sensitive, it would be expected that function would also be sensitive to the overexpression of ΔCAN, which is what we observe for WPRE function.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that LMB specifically inhibits NES-CRM1 interactions and directly blocks Rev-mediated export. In this study, LMB inhibited the nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA accumulation mediated by both Rev and WPRE but not that mediated by HPRE (lanes 6 in Fig. 4A and B). Prior studies (48) have also demonstrated that LMB treatment reduced the amounts of nuclear RRE RNAs. This suggests that the disruption of CRM1 function causes the unspliced nuclear RRE RNA and WPRE RNA to become unstable in the nucleus and probably to degrade. Alternatively, LMB may lower the amount of nuclear WPRE RNA available for export, which would result in a reduced amount of cytoplasmic WPRE RNA. However, the similar sensitivity and RNA accumulation profiles for WPRE- and RRE-containing RNAs suggests that part of the WPRE function is CRM1-dependent export. Support for this model comes from the observation that the overexpression of CRM1 stimulates WPRE function while having only a minimal effect on the activity of RRE/Rev and HPRE. Importantly, excess CRM1 causes a relative increase in the amount of cytoplasmic WPRE-containing messages relative to the nuclear pool of these messages. This shift is consistent with the increased amounts of CRM1 improving the efficiency of WPRE-mediated mRNA export.

The exact nature of the relationship between WPRE and CRM1 is presently unclear. CRM1 has not been shown to directly interact with RNA; hence, it is unlikely that the WPRE and CRM1 interact directly. One possibility is that CRM1 is involved in the shuttling of a factor essential for WPRE activity. The disruption of CRM1 function would prevent the shuttling of this hypothetical factor, disrupting WPRE function while not having a direct effect on RNA export. However, the similarity between the RRE and WPRE RNA accumulation profiles suggests that partial CRM1 dependence is more direct. Further support for a direct role of CRM1 in WPRE-mediated export is suggested, because CRM1 overexpression increases WPRE activity and the relative abundance of cytoplasmic WPRE-containing RNA. Finally, our studies with an artificial element containing Bul acting in concert with HPREβ support this idea. If HIV Rev can act synergistically with the CRM1-independent PREβ subelement, it is possible that a cellular equivalent of Rev is doing the same in mediating the action of the WPRE. A more likely scenario is that NES-containing cellular bridging factor(s), functionally similar to Rev, binds to the WPRE and mediates the export of WPRE-containing RNA via the CRM1 pathway. Hence, it will be interesting to identify the cellular adapter protein(s).

The observation that the efficient function of the WPRE is CRM1 dependent has interesting potential implications. The partial CRM1 dependence of the WPRE suggests, as discussed above, that WPRE may be a bona fide RNA export element.

Of potentially greater interest is the observation that WPRE function is both CRM1 dependent and independent. This result is rather surprising, since HPRE is CRM1 independent and HPRE and WPRE share a high degree of sequence similarity. However, the two elements have consistently shown significant functional differences, including the fact that WPRE exhibits a much greater posttranscriptional activity. This study demonstrates that the increased WPRE activity is due to a CRM1-dependent function for WPRE. When WPRE-transfected cells are treated with LMB or ΔCAN is overexpressed, WPRE activity is inhibited to the exact levels observed with HPRE. These data suggest that WPRE can utilize multiple cellular processing pathways that may function cooperatively. The potential for cooperativity between different processing pathways was addressed by testing whether CRM1-dependent Rev-mediated export can act cooperatively with the CRM1-independent HPREβ subelement. The observed synergistic activity suggests that it is possible that a cellular equivalent of Rev is doing the same in mediating the action of WPRE. There are interesting parallels between the activity of WPRE and the export of c-fos. Both are partially dependent on CRM1 function and appear to have the ability to utilize CRM1-dependent and CRM1-independent posttranscriptional pathways. These similarities suggest that the WPRE may be mimicking certain aspects of highly regulated cellular messages such as c-fos.

It is interesting to point out the WPRE can posttranscriptionally stimulate the expression of heterologous messages, which do not contain introns or other inhibitory sequences. This stimulatory ability is vector and transgene independent, making the WPRE a potentially important tool in situations, such as gene therapy or large-scale protein production, where optimal gene expression is advantageous. This ability is unique. Neither CTE nor HPRE can stimulate transgene expression. The unique combination of CRM1-dependent with CRM1-independent elements within WPRE may be responsible for its potent activity. For instance, one element could influence CRM1-dependent export, while another could increase the efficiency of 3′-end processing. This would be consistent with recent data demonstrating that intronless mRNA export elements could be involved in other steps of pre-mRNA processing beside nuclear export, such as splicing and polyadenylation (29). Many other observations suggest the existence of intimate links between the various steps in the posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression, particularly between splicing and downstream events, including mRNA export, translation, stability, and cytoplasmic localization (35, 36, 40, 42, 65). Therefore, the ability of the WPRE to facilitate multiple levels of RNA processing and export may lead to efficient handling of the transgene message in the nucleus and result in optimal gene expression. It seems probable that analysis of the WPRE function will lead to major insight into the steps governing the nuclear export and processing of cellular mRNA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Glen Otero and Jonathan Loeb for assistance and helpful discussions.

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grant AI35477 (T.J.H.) and Arthur Kramer. Ileana Popa was supported by the Sarswatiben M. Upadhyaya Scholarship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachi, A., I. C. Braun, J. P. Rodrigues, N. Pante, K. Ribbeck, C. von Kobbe, U. Kutay, M. Wilm, D. Gorlich, M. Carmo-Fonseca, and E. Izaurralde. 2000. The C-terminal domain of TAP interacts with the nuclear pore complex and promotes export of specific CTE-bearing RNA substrates. RNA 6:136-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogerd, H. P., A. Echarri, T. M. Ross, and B. R. Cullen. 1998. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus Rev and human T-cell leukemia virus Rex function, but not Mason-Pfizer monkey virus constitutive transport element activity, by a mutant human nucleoporin targeted to Crm1. J. Virol. 72:8627-8635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun, I. C., E. Rohrbach, C. Schmitt, and E. Izaurralde. 1999. TAP binds to the constitutive transport element (CTE) through a novel RNA-binding motif that is sufficient to promote CTE-dependent RNA export from the nucleus. EMBO J. 18:1953-1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan, C. M., I. E. Gallouzi, and J. A. Steitz. 2000. Protein ligands to HuR modulate its interaction with target mRNAs in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 151:1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cullen, B. R. 2000. Connections between the processing and nuclear export of mRNA: evidence for an export license? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daly, T. J., K. S. Cook, G. S. Gray, T. E. Malone, and J. R. Rusche. 1989. Specific binding of HIV-1 recombinant Rev protein to the Rev-response element in vitro. Nature 342:816-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donello, J. E., A. A. Beeche, G. J. Smith III, G. R. Lucero, and T. J. Hope. 1996. The hepatitis B virus posttranscriptional regulatory element is composed of two subelements. J. Virol. 70:4345-4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donello, J. E., J. E. Loeb, and T. J. Hope. 1998. Woodchuck hepatitis virus contains a tripartite postranscriptional regulatory element. J. Virol. 72:5085-5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emmermman, M., R. Vazeux, and K. Pedeu. 1989. The rev gene product of the human immunodeficiency virus affects envelope-specific RNA localization. Cell 57:1155-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ernst, R. K., M. Bray, D. Rekosh, and M.-L. Hammarskjold. 1997. Secondary structure and mutational analysis of the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus constitutive transport element. RNA 3:219-222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ernst, R. K., M. Bray, D. Rekosh, and M.-L. Hammarskjold. 1997. A structural retroviral element that mediates nucleocytoplasmic export of intron-containing RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:135-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felber, B. K., D. Derse, A. Athanassopoulos, M. Campbell, and G. N. Pavlakis. 1989. Cross-activation of the Rex proteins of HTLV-I and BLV and of the Rev protein of HIV-1 and nonreciprocal interactions with their RNA responsive elements. New Biol. 1:318-328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felber, B. K., M. Hadzopoulou-Cladaras, C. Cladara, T. Copeland, and G. Pavlakis. 1989. Rev protein of human immunodeficiency virus affects the stability and transport of viral mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:1496-1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher, U. J., J. Huber, W. C. Boelens, I. W. Mattaj, and R. Luhrmann. 1995. The HIV-1 Rev activation domain is a nuclear export signal that accesses an export pathway used by specific cellular RNAs. Cell 82:475-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fornerod, M., M. Ohno, M. Yoshida, and I. W. Mattaj. 1997. CRM1 is an export receptor for leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Cell 90:1051-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fornerod, M., J. Vandeursen, S. Vanbaal, A. Reynolds, D. Davis, K. Gopal Murti, J. Fransen, and G. Grosveld. 1997. The human homologue of yeast CRM1 is in a dynamic subcomplex with Can/Nup214 and a novel nuclear pore component nup88. EMBO J. 16:807-816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukuda, M., S. Asano, T. Nakamura, M. Adachi, M. Yoshida, M. Yanagida, and E. Nishida. 1997. CRM1 is responsible for intracellular transport mediated by the nuclear export signal. Nature 390:308-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallouzi, I. E., C. M. Brennan, and J. A. Steitz. 2001. Protein ligands mediate the CRM1-dependent export of HuR in response to heat shock. RNA 7:1348-1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallouzi, I. E., and J. A. Steitz. 2001. Delineation of mRNA export pathways by the use of cell-permeable peptides. Science 294:1895-1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goda, S. K., and N. P. Minton. 1995. A simple procedure for gel electrophoresis and Northern blotting of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:3357-3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gruter, P., C. Tabernero, C. von Kobbe, C. Schmitt, C. Saavedra, A. Bachi, M. Wilm, B. K. Felber, and E. Izaurralde. 1998. TAP, the human homolog of Mex67p, mediates CTE-dependent RNA export from the nucleus. Mol. Cell 1:649-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guzyk, B. W., L. Levesque, S. Prasad, Y.-C. Bor, B. E. Black, B. M. Pashal, D. Rekosh, and M.-L. Hammarskjold. 2001. NXT1 (p15) is a crucial cellular cofactor in TAP-dependent export of intron-containing RNA in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:2545-2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hope, T. J., B. L. Bond, D. McDonald, N. P. Klein, and T. G. Parslow. 1991. Effector domains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev and human T-cell leukemia virus type I Rex are functionally interchangeable and share an essential peptide motif. J. Virol. 65:6001-6007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hope, T. J., X. J. Huang, D. McDonald, and T. G. Parslow. 1990. Steroid-receptor fusion of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev transactivator: mapping cryptic functions of the arginine-rich motif. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:7787-7791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hope, T. J., N. P. Klein, M. E. Elder, and T. G. Parslow. 1992. Trans-dominant inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev occurs through formation of inactive protein complexes. J. Virol. 66:1849-1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hope, T. J., D. McDonald, X. J. Huang, J. Low, and T. G. Parslow. 1990. Mutational analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev transactivator: essential residues near the amino terminus. J. Virol. 64:5360-5366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang, J., and T. J. Liang. 1993. A novel hepatitis B virus (HBV) genetic element with Rev response element-like properties that is essential for expression of HBV gene products. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:7476-7486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang, X. J., T. J. Hope, B. L. Bond, D. McDonald, K. Grahl, and T. G. Parslow. 1991. Minimal Rev-response element for type 1 human immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 65:2131-2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang, Y., K. M. Wimler, and G. G. Carmichael. 1999. Intronless mRNA transport elements may affect multiple steps of pre-mRNA processing. EMBO J. 18:1642-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang, Z.-M., and T. S. B. Yen. 1995. Role of the hepatitis B virus posttranscriptional regulatory element in export of intronless transcripts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:3864-3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang, Z. M., W. Q. Zang, and T. S. Yen. 1996. Cellular proteins that bind to the hepatitis B virus posttranscriptional regulatory element. Virology 217:573-581. (Erratum, 240:382.) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Kang, Y., H. P. Bogerd, and B. R. Cullen. 2000. Analysis of cellular factors that mediate nuclear export of RNAs bearing the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus constitutive transport element. J. Virol. 74:5863-5871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang, Y., and B. R. Cullen. 1999. The human Tap protein is a nuclear mRNA export factor that contains novel RNA-binding and nucleocytoplasmic transport sequences. Genes Dev. 13:1126-1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katahira, J., K. Strasser, A. Podtelejnikov, M. Mann, J. U. Jung, and E. Hurt. 1999. The Mex67p-mediated nuclear mRNA export pathway is conserved from yeast to human. EMBO J. 18:2593-2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kataoka, N., J. Yong, V. N. Kim, F. Velazquez, R. A. Perkinson, F. Wang, and G. Dreyfuss. 2000. Pre-mRNA splicing imprints mRNA in the nucleus with a novel RNA-binding protein that persists in the cytoplasm. Mol. Cell 6:673-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim, V. N., J. Yong, N. Kataoka, L. Abel, M. D. Diem, and G. Dreyfuss. 2001. The Y14 protein communicates to the cytoplasm the position of exon-exon junctions. EMBO J. 20:2062-2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kjems, J., A. D. Frankel, and P. A. Sharp. 1991. Specific regulation of mRNA splicing in vitro by a peptide from HIV-1 Rev. Cell 67:169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kudo, N., N. Matsumori, H. Taoka, D. Fujiwara, E. P. Schreiner, B. Wolff, M. Yoshida, and S. Horinouchi. 1999. Leptomycin B inactivates CRM1/exportin 1 by covalent modification at a cysteine residue in the central conserved region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9112-9117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kudo, N., B. Wolff, T. Sekimoto, E. P. Schreiner, Y. Yoneda, M. Yanagida, S. Horinouchi, and M. Yoshida. 1998. Leptomycin B inhibition of signal-mediated nuclear export by direct binding to CRM1. Exp. Cell Res. 242:540-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le Hir, H., E. Izauralde, L. E. Maquat, and M. J. Moore. 2000. The spliceosome deposits multiple proteins 20-24 nucleotides upstream of mRNA exon-exon junctions. EMBO J. 19:6860-6869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loeb, J. E., W. S. Cordier, M. E. Harris, M. D. Weitzman, and T. J. Hope. 1999. Enhanced expression of transgenes from adeno-associated virus vectors with the woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element: implications for gene therapy. Hum. Gene Ther. 10:2295-2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo, M. J., and R. Reed. 1999. Splicing is required for rapid and efficient mRNA export in metazoans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:14937-14942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malim, M. H., and B. R. Cullen. 1993. Rev and the fate of pre-mRNA in the nucleus: implication for the regulation of RNA processing in eukaryotes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:6180-6189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malim, M. H., J. Hauber, S. E. Le, J. V. Maizel, and B. R. Cullen. 1989. The HIV-1 Rev trans-activator acts through a structured target sequence to activate nuclear export of unspliced viral mRNAs. Nature 338:254-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murata, T., F. Goshima, T. Koshizuka, H. Takakuwa, and Y. Nishiyama. 2001. A single amino acid substitution in the ICP27 protein of the herpex simplex virus type 1 is responsible for its resistance to leptomycin B. J. Virol. 75:1039-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neumann, G., M. T. Hughes, and Y. Kawaoka. 2000. Influenza A virus NS2 protein mediates vRNP nuclear export through NES-independent interaction with hCRM1. EMBO J. 19:6751-6758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O'Neill, R. E., J. Talon, and P. Palese. 1998. The influenza virus NEP (NS2 protein) mediates the nuclear export of viral ribonucleoproteins. EMBO J. 17:288-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Otero, G. C., M. E. Harris, J. E. Donello, and T. J. Hope. 1998. Leptomycin B inhibits equine infectious anemia virus Rev and feline immunodeficiency virus Rev function but not the function of the hepatitis B virus posttranscriptional regulatory element. J. Virol. 72:7593-7597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palmeri, D., and M. H. Malim. 1996. The human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 posttranscriptional trans-activator Rex contains a nuclear export signal. J. Virol. 70:6442-6445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pasquinelli, A. E., R. K. Ernst, E. Lund, C. Grimm, M. L. Zapp, D. Rekosh, M. L. Hammarskjold, and J. E. Dahlberg. 1997. The constitutive transport element (CTE) of Mason-Pfizer monkey virus (MPMV) accesses a cellular mRNA export pathway. EMBO J. 16:7500-7510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phillips, T. R., C. Varmont, D. Konings, B. Shacklett, C. Hamson, P. Luciw, and J. H. Elder. 1992. Identification of the Rev transactivation and Rev-responsive elements of feline immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 66:5464-5471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosin-Arbesfeld, R., M. Rivlin, S. Noiman, P. Mashiah, A. Yaniv, T. Miki, S. R. Tronick, and A. Gazit. 1993. Structural and functional characterization of rev-like transcripts of equine anemia virus. J. Virol. 67:5640-5646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saavedra, C., B. Felber, and E. Izauralde. 1997. The simian retrovirus-1 constitutive transport element, unlike the HIV-1 RRE, uses factors required for cellular mRNA export. Curr. Biol. 7:619-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sandri-Goldin, R. M. 1998. ICP27 mediates HSV RNA export by shuttling through a leucine-rich nuclear export signal and binding viral intronless RNAs through an RGG motif. Genes Dev. 12:868-879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Segref, A., K. Sharma, V. Doye, A. Hellwig, J. Huber, R. Luhrmann, and E. Hurt. 1997. Mex67p, a novel factor for nuclear mRNA export, binds to both poly(A)+ RNA and nuclear pores. EMBO J. 16:3256-3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Semmes, O. J., L. Chen, R. T. Sarisky, Z. Gao, L. Zhong, and S. D. Hayward. 1998. Mta has properties of an RNA export protein and increases cytoplasmic accumulation of Epstein-Barr virus replication gene mRNA. J. Virol. 72:9526-9534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soliman, T. M., and S. J. Silverstein. 2000. Herpesvirus mRNAs are sorted for export via CRM1-dependent and -independent pathways. J. Virol. 74:2814-2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stade, K., C. S. Ford, C. Guthrie, and K. Weis. 1997. Exportin 1 (Crm1p) is an essential nuclear export factor. Cell 90:1041-1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Strasser, K., J. Bassler, and E. Hurt. 2000. Binding of the Mex67p/Mtr2p heterodimer to FXFG, GLFG, and FG repeat nucleoporins is essential for nuclear mRNA export. J. Cell Biol. 150:695-706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Strasser, K., and E. Hurt. 2000. Yra1p, a conserved nuclear RNA-binding protein, interacts directly with Mex67p and is required for mRNA export. EMBO J. 19:410-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stutz, F., and M. Rosbash. 1998. Nuclear RNA export. Genes Dev. 12:3303-3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stutz, F., A. Bachi, T. Doerks, I. C. Braun, B. Seraphin, M. Wilm, P. Bork, and E. Izaurralde. 2000. REF, an evolutionary conserved family of hnRNP-like proteins, interacts with TAP/Mex67p and participates in mRNA nuclear export. RNA 6:638-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tiley, L. S., M. H. Malim, H. K. Tewary, P. G. Stockley, and B. R. Cullen. 1992. Identification of a high affinity RNA-binding site for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:758-762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zang, W. Q., and B. Yen. 1999. Distinct export pathway utilized by the hepatitis B virus posttranscriptional regulatory element. Virology 259:299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou, Z., M. J. Luo, K. Straesser, J. Katahira, E. Hurt, and R. Reed. 2000. The protein Aly links pre-messenger-RNA splicing to nuclear export in metazoans. Nature 407:401-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zufferey, R., J. E. Donello, D. Trono, and T. J. Hope. 1999. Woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element enhances expression of transgenes delivered by retroviral vectors. J. Virol. 73:2886-2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]