Abstract

We report an extremely rare entity in which all coronary arteries originate from the pulmonary artery. Only a few cases have been reported and corrected, and fewer still have had a favorable outcome. The survival range reported for these patients is from 9 hours to 1 year. This case was diagnosed and surgically corrected in a patient at the age of 2 months, and the patient is doing well 27 months after the procedure.

Key words: Abnormalities, multiple; coronary vessel anomalies/surgery; heart defects, congenital/surgery; infant; pulmonary artery/abnormalities; sinus of Valsalva/abnormalities

We report an extremely rare entity in which all coronary arteries arise from the pulmonary artery. Only a few cases have been reported and corrected; to our knowledge, only 2 of these had a favorable outcome.

Case Report

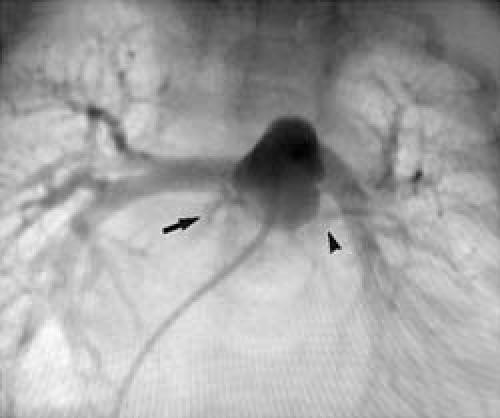

In April 2003, a 2-month-old male infant was first seen by a pediatrician because of respiratory distress and irritability. His physical examination revealed a systolic murmur and hepatomegaly. The respiratory rate was 70 breaths per minute. Chest radiography showed severe cardiomegaly and pulmonary edema. The electrocardiogram showed acute anteroseptal myocardial infarction accompanied by elevation of cardiac enzymes. On admission, the creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level was 931 IU/L (normal range, 46–134 IU/L), the CK-MB was 52.3 IU/L (normal, 2.3–9.5 IU/L), and a result from a qualitative troponin test was positive. His echocardiographic studies revealed severe ventricular dilatation with diffuse hypokinesia and dyskinesia of the anterior apical segment, and an ejection fraction of less than 0.20. Further, echocardiography suggested an anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA). The infant had a heart catheterization. His right heart pressures were: ventricle, 40/4 mmHg; and pulmonary artery, 40/12 mmHg (median, 20 mmHg). His left heart pressures were: ventricle, 58/10–18 mmHg; and aorta, 56/32 mmHg (median, 41 mmHg). Angiographic studies revealed an anomalous origin of both coronary arteries from the right anterior sinus of Valsalva of the pulmonary artery, with 2 adjacent ostia (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1 Preoperative aortogram, without coronary arteries.

Fig. 2 Note that both the right (arrow) and left (arrowhead) coronary arteries arise from the pulmonary artery.

Emergency corrective surgery was performed. The patient was placed on extracorporeal circulation with membrane oxygenation. A single venous cannula was placed in the right atrium. Systemic hypothermia at 20 °C was induced. The pulmonary artery and the aorta were transected 1.5 cm above the aortic and pulmonary roots. The location of both coronary arteries was side by side, at the right anterior Valsalva sinus of the pulmonary artery. The coronary arteries were totally separated by 1.5 to 2.0 mm, and the left main trunk progressed epicardially behind the pulmonary artery. We resected a cuff that included both ostia. A V-shaped incision was made in the left anterior aortic sinus of Valsalva. A suture was placed at the distal end of the coronary cuff and in the lower vertex of the V-shaped incision of the aortic sinus. Particular care was used in order to avoid kinking or twisting the coronary pedicle at transfer. Therefore, it was not necessary to place a pericardial patch, as suggested by Castañeda.1

Patch plasty of the aorta and pulmonary artery were performed with the use of a pericardial graft, in order to avoid obstruction. We verified that the coronary arteries did not have axial torsion. An atrial septal defect was corrected during a 7-minute circulatory arrest. Weaning the patient from extracorporeal circulation required the use of inotropic agents at therapeutic doses. The sternum was left open for only 48 hours.

Left phrenic paralysis was diagnosed on hospital day 26 and was treated with a diaphragmatic placation. On the 45th hospital day, we diagnosed moderate supravalvular aortic stenosis, with a systolic pressure gradient of 40 mmHg. In a catheter procedure, an 8.0-mm balloon dilation achieved a residual gradient of 20 mmHg. During this procedure, we obtained an aortogram that showed vascularization of both coronary arteries (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Postoperative aortogram shows revascularization of both coronary arteries.

On discharge (hospital day 53), an echocardiographic study revealed a dramatic recovery of myocardial contractility, with an ejection fraction of more than 0.50 and left ventricular posterior wall thickness of 54 mm. The electrocardiogram had no Q waves, CPK was 85 IU/L, and CK-MB was 4.6 IU/L. The patient is doing well clinically at 27 months after the surgery, and his last echocardiogram showed the same 20-mmHg gradient.

Discussion

Congenital anomaly of the coronary arteries constitutes a group of congenital anomalies that occurs in 1% to 2% of congenital malformations.2 The most common coronary anomaly is ALCAPA, an entity described by Brooks in 18853 that has an incidence of 1 in 300,000 live births.4 Anomalous origin of both coronary arteries has been reported in only a few cases.2,4–6,9,10

Patients with ALCAPA have clinical manifestations due to heart failure and low cardiac output. Without surgical correction, 75% develop chronic heart failure by the age of 4 months, and, if left untreated, the mortality rate is 80% to 90% by the 1st year,8 mainly due to heart failure and arrhythmias.7 In exceptional cases, patients with ALCAPA may reach adult life without symptoms. The symptoms of anomalous origin of a coronary artery from the pulmonary artery depend on the amount of collateral vascularization and on which artery is affected.8 Anomalous origin of both coronary arteries is considered to be incompatible with life.2,7 We have no certain explanation of why this baby survived his first 2 months of life. At the preoperative catheterization, the ductus arteriosus was found closed. We can hypothesize that it had been patent until symptoms were first noticed.

The pathologic condition that we present is extremely rare and considered fatal. The survival range reported for these patients is from 9 hours to 1 year.2,10 An extensive review of the medical literature uncovered only 2 other cases of survival after a corrective attempt.10

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Enrique Ochoa-Ramírez, MD, Av. Morones Prieto #3000-602, Colonia Doctores, Centro Medico Hospital, San José TEC de Monterrey, Monterrey, Nuevo León 64710, Mexico

E-mail: dimasmateos@yahoo.com

References

- 1.Castenada RA, Jonas AR, Mayer EJ, Hanley LF. Figure 26.3 in: Cardiac surgery of the neonate and infant. Philadelphia: WB Sanders; 1994. p. 421–2.

- 2.Fernandes ED, Kadivar H, Hallman GL, Reul GJ, Ott DA, Cooley DA. Congenital malformations of the coronary arteries: the Texas Heart Institute experience. Ann Thorac Surg 1992;54:732–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Brooks SJ. Two cases of abnormal coronary artery of the heart arising from the pulmonary artery. J Anat Physiol 1886;20:26. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Dodge-Khatami A, Mavroudis C, Backer CL. Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project: anomalies of the coronary arteries. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;69(4 Suppl):S270–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Santoro G, di Carlo D, Carotti A, Formigari R, Boldrini R, Bosman C, Ballerini L. Origin of both coronary arteries from the pulmonary artery and aortic coarctation. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;60:706–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Heusch A, Quagebeur J, Paulus A, Krogmann ON, Bourgeois M. Anomalous origin of all coronary arteries from the pulmonary trunk. Cardiology 1997;88:603–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.McKellar. Coronary artery anomalies. Available from URL: http://www.ctsnet.org/doc/4575. Last revised Sep 25, 2001.

- 8.Nicholson WJ, Schuler B, Lerakis S, Helmy T. Anomalous origin of the coronary arteries from the pulmonary trunk in two separate patients with a review of the clinical implications and current treatment recommendations. Am J Med Sci 2004;328:112–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Goldblatt E, Adams AP, Ross IK, Savage JP, Morris LL. Single-trunk anomalous origin of both coronary arteries from the pulmonary artery. Diagnosis and surgical management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1984;87:59–65. [PubMed]

- 10.Urcelay GE, Iannettoni MD, Ludomirsky A, Mosca RS, Cheatham JP, Danford DA, Bove EL. Origin of both coronary arteries from the pulmonary artery. Circulation 1994; 90:2379–84. [DOI] [PubMed]