Patient 1

A 50-year-old man with a history of hemochromatosis presented with signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure. Coronary angiography revealed nonobstructive coronary disease. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) was performed in order to evaluate and quantitate left ventricular (LV) function, and to determine cardiac and hepatic iron content (Fig. 1).

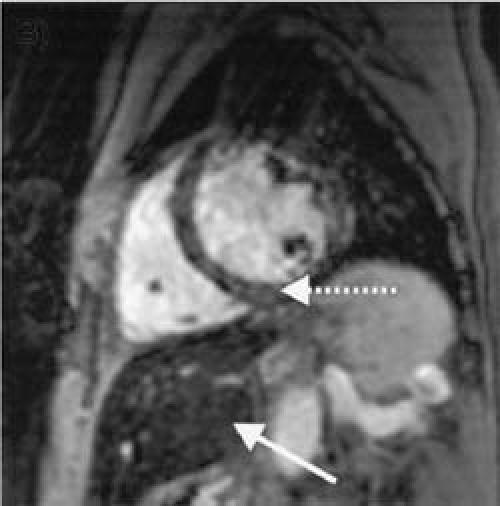

Fig. 1 Patient 1: Hemochromatosis with cardiomyopathy, but without myocardial iron deposition. A short-axis view of the heart reveals moderate hepatic iron deposition (solid arrow; hepatic T2*, 11 msec [normal, >19 msec]) manifested by a relatively dark liver parenchyma. Conversely, the cardiac muscle remains relatively bright, indicating that there is no iron deposition in the myocardium (dotted arrow; cardiac T2*, 49 msec [normal, >20 msec]). However, the left ventricle is enlarged, and there is severe global left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction, 0.17; end-diastolic volume, 441 cc).

Patient 2

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging was requested to determine the myocardial iron content in a 53-year-old man who had been diagnosed with hemochromatosis 2 years earlier. He had no exercise limitations (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Patient 2: Hemochromatosis with myocardial iron deposition. A short-axis view of the heart reveals that both the heart and the liver have low signal intensity (are dark). These results indicate that there is severe iron deposition in both the liver (solid arrow; hepatic T2*, 7 msec) and the heart (dotted arrow; cardiac T2*, 10 msec). Furthermore, there is moderate global left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction, 0.36; end-diastolic volume, 352 cc).

Comment

Iron overload states can be secondary to hereditary hemochromatosis, hematologic diseases such as thalassemia major, sideroblastic and chronic hemolytic anemias, chronic liver disease, and other miscellaneous conditions.1 Serum iron and ferritin content have limited ability to predict myocardial iron content.2 Within the human body, iron is stored either as water-soluble ferritin with a crystalline core or as water-insoluble hemosiderin. Paramagnetic ferritin and hemosiderin interact with nearby hydrogen nuclei in tissue water and shorten the relaxation times, T1, T2, and T2* (pronounced “T2-star”), leading to changes in the magnetic resonance (MR) signal intensity and altering local magnetic susceptibility.2 Recent work by Anderson and colleagues2 has shown that T2* imaging can be highly sensitive in detecting myocardial iron deposition, and in patients with moderate-to-severe iron deposition; T2* values are substantially reduced—from the normal values of approximately 50 msec or greater to less than 20 msec. When T2* is less than 20 msec, LV systolic function is seen to decline progressively, accompanied by an increase in LV end-systolic volume index and LV mass.

In our laboratory, MRI signal decay is sampled following a 90° excitation pulse with 17 gradient echoes at different echo times with gradient oscillations. Magnetic resonance imaging data are collected during diastole with vector cardiogram gating, and with real-time respiratory navigators to avoid data corruption due to cardiac pulsation and respiration. Signal intensities from the multiple echo times are fitted to an exponential decay curve to estimate regional T2* and, thus, iron deposition concentrations.

In Patient 1, there was severe global dysfunction, but no significant myocardial iron deposition despite moderate hepatic deposition. Coronary angiography revealed nonobstructive disease, suggesting a diagnosis of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Patient 2 had moderate global reduction in ejection fraction and severe myocardial and hepatic iron deposition, suggesting a cause for the LV dysfunction.

Left ventricular systolic dysfunction is a late sign of iron toxicity, and the prognosis is poor in the late stages. Early identification of iron-deposition cardiomyopathy enables early intensification of iron chelation therapy, which might improve a patient's chance of survival.3 However, serologic measurements bear little relation to the degree of iron deposition and cannot be used to measure myocardial iron deposition or to monitor therapeutic response to treatment. T2* CMR is a novel, noninvasive, and accurate method for the diagnosis and monitoring of patients at risk for iron-deposition cardiomyopathy.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Scott D. Flamm, MD, St. Luke's Episcopal Hospital, MC 2-270, 6720 Bertner Ave., Houston, Texas 77030

E-mail: sflamm@sleh.com

References

- 1.Tavill AS; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; American College of Gastroenterology; American Gastroenterological Association. Diagnosis and management of hemochromatosis. Hepatology 2001;33:1321–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Anderson LJ, Holden S, Davis B, Prescott E, Charrier CC, Bunce NH, et al. Cardiovascular T2-star (T2*) magnetic resonance for the early diagnosis of myocardial iron overload. Eur Heart J 2001;22:2171–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Porter JB. Practical management of iron overload. Br J Haematol 2001;115:239–52. [DOI] [PubMed]