More evidence for the “use it or lose it” approach to ageing has come from a study published this week showing that older adults who exercised three or more times a week had a significantly lower risk of developing dementia than adults who exercised less (Annals of Internal Medicine 2006;144: 73-81).

The study included a randomly selected group of 1740 adults aged 65 years or older with normal cognitive function, as assessed by the Cognitive Ability Screening Instrument, at baseline. Participants were examined to identify incident dementia every two years at the same time as they reported their exercise patterns. A session of exercise was defined as at least 15 minutes of physical activity at any one time, including walking, hiking, aerobics, callisthenics, swimming, water aerobics, weight training, and stretching.

In a mean follow-up of 6.2 years, 158 people developed dementia, and, of these, 107 were diagnosed as having Alzheimer's disease.

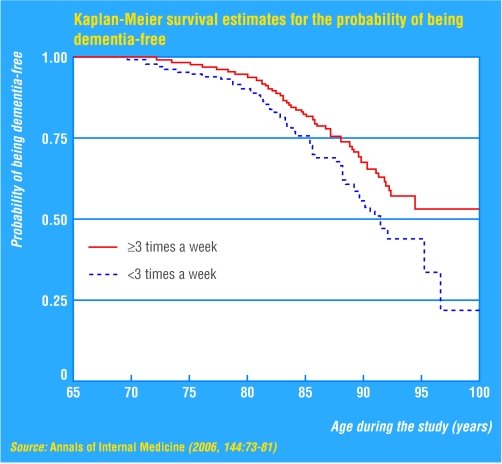

The incidence of dementia was 13.0 per 1000 person years for people who exercised at least three times a week, compared with 19.7 per 1000 person years for people who exercised less often. This meant that the risk of developing dementia was 38% lower in the regular exercise group, with an age and sex adjusted hazard ratio of 0.62 (95% confidence interval 0.44 to 0.86; P=0.004).

Figure 1.

The risk reduction associated with exercise was greater in people with lower performance levels at baseline, than in those with higher performance at baseline, who continued to exercise.

Eric Larson, director of the Center for Health Studies at Group Health Cooperative, a health maintenance organisation in Seattle, and lead author of the study, said, “This is the most definitive study yet of the relationship between exercise and risk for dementia. Previous research on this relationship has yielded mixed results. We learnt that a modest amount of exercise would reduce a person's risk of dementia by about 40%. That's a significant reduction.

“The group that benefited the most were the people who were frailest at the start of the study. So this means that older people really should `use it even after you start to lose it,' because exercise may slow the progression of age related problems in thinking.”

Supplementary Material

Longer versions of these articles are on bmj.com

Longer versions of these articles are on bmj.com

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.