Abstract

The E2F family of transcription factors comprises six related members which are involved in the control of the coordinated progression through the G1/S-phase transition of cell cycle or in cell fate decision. Their activity is regulated by pocket proteins, including pRb, p107, and p130. Here we show that E2F1 directly interacts with the ETS-related transcription factor GABPγ1 in vitro and in vivo. The binding domain interacting with GABPγ1 was mapped to the C-terminal amino acids 310 to 437 of E2F1, which include its transactivation and pRb binding domain. Among the E2F family of transcription factors, the interaction with GABPγ1 is restricted to E2F1. DNA-binding E2F1 complexes containing GABPγ1 are characterized by enhanced E2F1-dependent transcriptional activity. Moreover, GABPγ1 suppresses E2F1-dependent apoptosis by mechanisms other than the inhibition of the transactivation capacity of E2F1. In summary, our results provide evidence for a novel pRb-independent mechanism regulating E2F1-dependent transcription and apoptosis.

The transcription factor E2F1 plays a pivotal role in the coordinated expression of genes necessary for cell cycle progression and division (7). Overexpression of E2F1 drives quiescent cells into S phase (17, 21, 24). Ectopic expression of E2F1 also leads to apoptosis, which is specific to E2F1 and not other E2F family members (13, 34, 39). E2F interacts with DP proteins to form a heterodimer and binds to DNA in a sequence-specific manner (12). E2F-dependent transcriptional activation is principally regulated by interaction with a member of the retinoblastoma gene family (pRb) (11, 33, 43). Furthermore, E2F-binding sites in a given promoter were shown to be regulated by different E2Fs in a cell cycle-dependent fashion (42). Transcriptional studies in vitro have identified the existence of three types of E2F/pRb complexes (7). In activator E2F complexes, the E2F transactivation domain drives transcription in the absence of pRb. In inhibited E2F/pRb complexes, the transactivation domain of E2F1 is blocked by bound pRb, rendering E2F transcriptionally inactive. In repressor E2F complexes, pRb is recruited to E2F-binding sites by E2F and inhibits promoter activation by E2F with or without further utilization of histone-modifying enzymes (2, 26, 35, 48). During G0 and early G1, pRb is hypophosphorylated and carries a stably bound E2F. In mid-G1 pRb is inhibited by phosphorylation through cyclin-dependent kinases cdk4/6 and cdk2, liberating the inhibition of E2F activity (3). Released E2F then activates cellular genes involved in DNA replication and cell cycle progression: cdk2, cdc2, cdc25A, cyclins E and A, histone H2A, c-myc, cdc6, B-myb, dihydrofolate reductase, thymidine kinase, pRb, E2F, and DNA polymerase α (4, 15, 16, 30, 50).

Very little is known about the function of E2F1 during development and differentiation of cardiomyocytes. Recently, it has been shown that adenovirus-mediated gene delivery of E2F1 or E1A induced DNA synthesis in isolated rat ventricular cardiomyocytes (19, 20, 44). Ectopic expression of E2F1 in cardiomyocytes also resulted in an increase in the expression of key cell cycle activators and the induction of apoptosis, which was accompanied by concomitant loss of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21CIP1 and p27KIP1 (44). To investigate the potential role of E2F1, which is expressed in the heart (44), a yeast-based, two-hybrid assay was used to screen for E2F-interacting proteins in a human adult heart cDNA library. By this approach, we identified GABPγ1 as an E2F1-binding protein. The ETS-related GA-binding protein GABPγ1 binds to GABPα and confers the ability to stimulate transcription in vitro (6, 37, 38, 41, 47). GABPα was originally identified as a factor responsible for transcription from the adenovirus E4 promoter (46). GABP is a target of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (5, 24) cascade and functions as a critical nuclear integrator of these ubiquitous signaling pathways (45). Here we show that E2F1 and GABPγ1 interact in vivo as demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins from cardiomyocyte extracts. In transiently transfected Saos-2 cells, GABPγ1 led to an enhanced E2F1-dependent transcriptional activation and repressed E2F1-mediated apoptosis. Moreover, GABPγ1 suppressed E2F1-dependent apoptosis by mechanisms other than the inhibition of the transactivation potential of E2F1. Our study suggests that factors other than pRb may also control E2F-dependent transactivation and apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and transient transfections.

Saos-2 and Cos-7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and were grown in Dulbecco minimal essential medium/F12 medium (GIBCO) supplemented with antibiotics, l-glutamine, and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (GIBCO) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Y190 reporter host strain was maintained on yeast extract-peptone-dextrose medium at 30°C in an air incubator. For selection of the specific phenotype, yeast transformants were grown on synthetic dropout medium (medium lacking tryptophan, leucine, and histidine) supplemented with 50 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT; Sigma). Escherichia coli DH5α was used for plasmid propagation, E. coli BL21 for production of glutathione transferase (GST) fusion proteins, and E. coli HB101 for selection of library plasmids. For in vivo interaction assays Cos-7 cells were grown in 100-mm-diameter dishes to 70% confluency. Adherent cells were transfected with 10 μg of pcDNA3.1-E2F1 and/or 15 μg of pCAGGS-GABPγ1 for 6 h in a total volume of 2.5 ml. All transfections were done using the cationic liposomal transfection reagent DAC-30 (R. Rezka, Max-Delbrück Center, Berlin, Germany). Cells were then serum starved for 18 h. Growth medium (10 ml, 10% FCS) was added, and the cells were incubated further for a total of 48 h. Transfection efficiency was between 30 and 40% as evaluated by cotransfection of 0.5 μg of a cytomegalovirus (CMV)-driven green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression plasmid (pEGFP-N1; Clontech).

Two-hybrid screens.

The E2F1 cDNA comprising amino acids 243 to 437 was PCR cloned as a BamHI fragment in frame with the Gal4 DNA-binding domain of pAS2-1 (Clontech) and was used as bait for the yeast two-hybrid screen. This E2F1 bait comprised the marked box, the transactivation region, and the pRb interaction domain but lacked the N-terminal cyclin A-binding region, the DNA-binding domain, and most of the dimerization region. A randomly cloned human adult heart cDNA library (HL4013AB, lot 51034; Clontech) fused to the Gal4 activation domain of pGAD10 was used as prey. Yeast Y190 cells were simultaneously cotransformed with pAS2-1-E2F1 plasmid and pGAD10 library plasmid by using standard lithium acetate transformation procedures. Yeast transformant mixtures were plated on synthetic dropout medium and were incubated for 5 to 8 days. For confirmation of protein interaction, the primary His+ transformants were tested for expression of the second reporter gene lacZ by using a colony lift β-galactosidase filter or liquid assay. Approximately 7 × 106 transformants were screened for their ability to grow in the absence of histidine, and 183 positive colonies were identified. For elimination of the DNA-binding domain plasmid pAS2-1-E2F1, chemically competent E. coli HB101 (LeuB−) was transformed with plasmid DNA isolated from yeast and grown on M9 medium lacking l-leucine. Selectively recovered library plasmids were transformed into E. coli DH5α, and each individually cDNA was sequenced using the big dye terminator cycle sequencing kit according to the manufacturer's specifications (Abiprism; Perkin-Elmer). Clones containing cDNAs encoding proteins of the respiratory chain or the contractile apparatus or which were in the antisense orientation and/or out of frame were discarded. The remaining 17 clones were retransformed into yeast Y190 and screened for fortuitous interaction with pLAM5′-1 encoding a Gal4 DNA-binding/human lamin C hybrid (Clontech; data not shown).

In vitro protein interaction assays.

For GST fusion binding assays, cDNAs encoding C-terminal GST fusion proteins for DP1, wild-type (wt) E2Fs, and various truncated E2F1 mutants were PCR cloned as a BamHI construct into the pGex-1λT vector (Pharmacia). GST-GABPα, -GABPβ1, or -GABPγ1 and E2F1 (Δ277-350) were in pGex-2λT. For generation of GST fusion proteins, 100 ml of Luria-Bertani medium containing 100 μg of penicillin/ml was inoculated with 5 ml of overnight culture of E. coli BL21 cells transformed with GST fusion protein plasmids. After 1 h, protein expression was induced by addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Sigma) for 4 h with shaking at 220 rpm and at 37°C. Cellular extracts were prepared by lysis for 20 min at 4°C with 2.0 ml of NETN buffer composed of 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% (vol/vol) NP-40, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1.0 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1.0 mg of lysozyme (Sigma)/ml, 50 U of DNase I (Sigma)/ml, and 1.0 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Crude extracts were sonicated for 1 min and cleared by centrifugation at 18,000 × g at 4°C for 30 min. In vitro binding assays were performed by immobilizing equal amounts of GST fusions for 30 min at room temperature on 25 μl of glutathione Sepharose 4B beads (Pharmacia) preblocked for 30 min with 1.0% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (fraction V; Sigma) in NETN binding buffer with the omission of DNase I. For in vitro transcription/translation reactions of GABPα-, GABPβ1-, or GABPγ1 cDNAs in pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen), a T7 RNA polymerase-dependent, TNT-coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega) and l-[35S]methionine (37 TBq/mmol; Amersham) were used according to the manufacturer's procedure. Control reactions contained no plasmid DNA. Briefly, 50μl of reticulocyte lysate mixture containing 2.0 μl of fresh l-[35S]methionine and 2.0 μg of plasmid DNA was incubated for 90 min at 30°C. The translation mixture was added to immobilized GST fusion proteins in 250 μl of NETN binding buffer. The binding reaction was performed overnight at 4°C on a rotating wheel. After incubation, the pellets were washed three times with NETN buffer at 4°C, and bound proteins were eluted by boiling in 30 μl of sample buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1.0 mM EDTA, 1.0% [wt/vol] DTT, 2.0% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], and 0.01% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue) for 3 min. Samples (30 μl) were subjected to SDS-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and the dried gels were subjected to autoradiography.

Preparation of cellular extracts.

Cos-7 cells were lysed in a buffer composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 5.0 mM EDTA, 5.0 mM DTT, 1.0 μg of leupeptin/ml, 2.0μg of aprotinin/ml, 5.0 mM NaF, and 0.1 mM Na3VO4 (all from Sigma) for 30 min on ice and sonicated for 5 s, and cellular extracts were centrifuged for 30 min at 18,000 × g at 4°C. The protein content was determined with the Coomassie protein assay (Pierce). Neonatal ventricular cardiomyocytes (2 × 106 cells) were isolated as decribed earlier (42) and were lysed in 500 μl of radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (10 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.0, 300 mM NaCl, 0.1% [wt/vol] SDS, 1.0% [vol/vol] NP-40, 1.0% [wt/vol] Na-deoxycholate, 2.0 mM EDTA, 1.0 mM DTT, and protease/phosphatase inhibitors as described) for 30 min on ice.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

The following antibodies were used: E2F1 (sc-193), DP1 (sc-610), p27KIP1 (sc-527), pRb (sc-050), and p130 (sc-317; all from Santa Cruz) and GFP (rabbit polyclonal; Clontech). Mouse monoclonal antisera to GABPα or GABPβ1 or rabbit polyclonal antiserum to GABPγ1 was kindly provided by H. Handa (Tokyo Institute of Technology, Yokohama, Japan). Cellular extracts (500 μg of total protein in 500 μl of 1.0-mg/ml BSA in lysis buffer) were incubated with 50 μl of protein A- or (for mouse monoclonal antibodies) protein G-agarose beads (Roche) preblocked with 1.0% (wt/vol) BSA in lysis buffer and were incubated with antibodies (1.0 μg/ml) overnight at 4°C on a rotating wheel. For coimmunoprecipitation studies, immunocomplexes were dissociated in 25 μl of lysis buffer containing 1.0% (wt/vol) SDS. Lysis buffer was added to give a final concentration of 0.1% SDS, and the supernatant was incubated with 50 μl of protein A-agarose beads for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to fresh protein A-agarose beads; antibodies to pRb, p130, E2F1, or GABPβ1 and p27KIP1 as negative controls were added and were incubated for 2 h at 4°C. Immune complexes were then washed three times with lysis buffer and were eluted in 50 μl of SDS sample buffer. Boiled samples (25 μl) were electrophoretically separated, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and blocked, and primary antibodies (0.2 to 1.0 μg/ml) were incubated overnight at 4°C on a rotary platform with gentle agitation. They were subsequently probed with secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRF)-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibodies (diluted 1:5,000; Amersham). Equal loading was confirmed by resolving 50 μg of total protein by SDS-PAGE and probing with anti-GFP or anti-sarcomeric actin antibody (Mob 128, diluted 1:200; Biotrend). Detection was carried out using the enhanced chemiluminescence assay (Amersham).

Immunofluorescence and in situ apoptosis assay.

Unless otherwise stated, solutions were made in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 1.0 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.2), and manipulations were performed at room temperature. Saos-2 cells grown on 10-mm-diameter coverslips were transfected with various combinations of either 1.0 μg of pcDNA3.1-E2F1, E2F1 (1-374), E2F1 (132), or E2F1Δ24; 0.5 μg of pcDNA3.1-DP1; 2.0 μg of pcDNA3.1-GABPγ1; or 2.0 μg of GABPβ1 and 0.05μg of pEGFP-N1 using the cationic liposomal reagent DAC-30. The transfection efficiency was in the range of 30 to 40%. At 24 h after transfection, cells were fixed with 3.7% formalin for 10 min. Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 for 10 min and blocked in 5.0% goat serum (Sigma)-0.2% (vol/vol) Tween 20 for 1 h. Cells were then incubated with primary antibodies (diluted 1:40 in blocking buffer) overnight at 4°C on a rotary shaker with gentle agitation. Samples were washed twice with PBS-0.1% (vol/vol) NP-40 (Roche) and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody (diluted 1:100 in PBS-0.1% NP-40; Sigma) for 1 h. Cells were incubated with mouse monoclonal antibody to anti-actin (diluted 1:100 in PBS-0.1% NP-40) for 1 h and subsequently with tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse antibody (diluted 1:100 in PBS-0.1% NP-40; Sigma) for 1 h. Slides were then mounted in glycerol-2.5% (wt/vol) 1,4-diazabicyclo-[2.2.2]octane (DABCO; Sigma) and were examined by fluorescence microscopy. For in situ detection of fragmented genomic DNA, a terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay was used according to the manufacturer's instructions (ApoAlert DNA fragmentation assay kit; Clontech). All immunofluorescence experiments were performed on three coverslips and repeated twice. For the quantitative analyses 200 nuclei were counted in random fields. Statistical significance was determined using the unpaired t test (StatView software). P of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

Exponentially growing Saos-2 cells in six-well plates (5.0 × 105 cells) were transfected with various combinations of either 3.0 μg of pcDNA3.1-E2F1, E2F1 (1-374), E2F1 (132), or E2F1 Δ24; 1.0 μg of pcDNA3.1-DP1; 5.0 μg of pcDNA3.1-GABPγ1; or 5.0 μg of GABPβ1. For identification of transfected cells, 0.1 μg of GFP expression plasmid was cotransfected. Cells were then growth arrested by serum starvation for 24 h. Cell cycle progression was reinitiated by addition of growth medium containing 10% FCS, and cells were cultivated for 18 h. At approximately 48 h after transfection, trypsinized cells were blocked with 20% FCS in PBS to prevent clumping, fixed in 70% ethanol for 2 h, permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100-PBS for 20 min, and stained with 10 μg of propidium iodide (Sigma)/ml in PBS. Samples (104 cells) were analyzed with a flow cytometer (Coulter Epics). Only GFP-positive cells were gated for cell cycle analysis by applying Epics software.

Transactivation assays.

The following luciferase constructs were used in transactivation assays: pI-H2A-68 (containing a TATA box, a CAAT box, and an E2F consensus binding site, 5′-TTTCGCGC-3′) and pI-H2A-68∗ (identical to pI-H2A-68 except for the mutated E2F site 5′-GGATCTCC-3′) (30). Saos-2 cells (5.0 × 105) exponentially grown in six-well plates were transfected using the cationic liposomal reagent DAC-30 with 3.0 μg of either pcDNA3 1-E2F1, E2F1 (1-374), E2F1 (E132), or E2F1 Δ24; 1.0 μg of pcDNA3.1-DP1; and 6.0 μg of pCMV-HA-pRb (kindly provided by C. Brandt, Max Delbrück Center); 5.0 μg of pcDNA3.1-GABPα; 5.0 μg of GABPβ1; 5.0 μg of GABPγ1; 3.0 μg of pI-H2A-68; 3.0 μg of pI-H2A-68∗; and 0.5 μg of pSV-β-galactosidase. Luciferase assays were carried out using Promega's luciferase assay system with reporter lysis buffer and a Berthold LB 9501 luminometer. Whole-cell lysates were incubated on ice for 20 min, sonified for 5 s, and centrifuged for 30 min at 18,000 × g at 4°C. For determination of luciferase activity, 20-μl cellular extracts (2 to 3 μg/μl of total protein) were used. To correct for transfection efficiencies, the activity of β-galactosidase in the lysate was measured using standard methods.

Gel shift assays.

Saos-2 cells were transfected with CMV-driven E2F1, DP1, GABPβ, and GABPγ1 expression plasmids as described above. Transfected cells were lysed in a buffer (12) composed of 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 0.42 M NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, and 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (all from Sigma) and 25% (vol/vol) glycerol for 30 min on ice and sonicated for 5.0 s, and cellular extracts were centrifuged for 60 min at 18,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatants were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at−80°C. Cell extracts (2.0 μl containing 2 to 5 μg of total protein) were added directly to 15 μl of binding buffer (12) (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 40 mM KCl, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% NP-40) and 1.0 μl (2.0 μg) of sonified herring sperm DNA (Sigma). Antibodies were concentrated using Centricon-3 microconcentrators according to the manufacturer's procedures (Amicon). The antibody concentration was adjusted to 1.0 μg/μl with binding buffer. To prove the presence of specific proteins, 1.0 μl of antibody solution was included in the binding reaction. The E2F probe (ATTTAAGTTTCGCGCCCTTTCCAA; synthesized by BioTez, Berlin, Germany) and the mutant E2F probe (ATTTAAGTTTCGatCCCTTTCCAA) (boldfacing indicates the E2F recognition sequence; lowercasing indicates mutated bases) (49) were end labeled with polynucleotide kinase (NEB) and [γ-32P]ATP (111 MBq/mmol; New England Nuclear). An aliquot of 0.5 ng (1.0 μl in binding buffer) of 32P-labeled wt E2F oligonucleotide was included in the binding reaction. The reaction mixture was incubated for 60 min at room temperature. To test the specificity of binding, a 100-fold oligonucleotide excess (50 ng; 1.0 μl in binding buffer) of either wt or mutant E2F DNA-binding site was included in the reaction mixture. The reaction solutions were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel in 0.25× Tris-borato-EDTA at 180 V for 5 h after the gel was prerun for 1 h at 180 V. The dried gel was analyzed using a PhosphorImager and TINA software (Raytest).

Northern blotting.

Saos-2 cells (106 cells) grown in six-well plates were washed once with ice-cold PBS and were lysed with 1.0 ml of Trizol (Gibco). Total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's procedure. A 15-μg portion of total RNA was resolved on a denaturing 1.5% agarose-formaldehyde gel, electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (OPTITRAN BA-S85; Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany), and cross-linked (UV-Stratalinker; Stratagene). PCR-amplified full-length human cDNAs (100 to 200 ng) to Apaf-1, caspase 3, and caspase 7 were nick labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (111 MBq/mmol; NEN) and the multiprime DNA-labeling system (Pharmacia). Unbound radioactivity was removed applying Microspin G-25 columns according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pharmacia Biotech). The membranes were reprobed to assess equivalent loading with a full-length rat glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (GAPDH)-cDNA probe. The amount of incorporated radioactive label was quantified with a PhosphorImager and TINA software (Raytest).

RESULTS

Two-hybrid screen reveals interaction of GABPγ1 with the transactivation domain of E2F1.

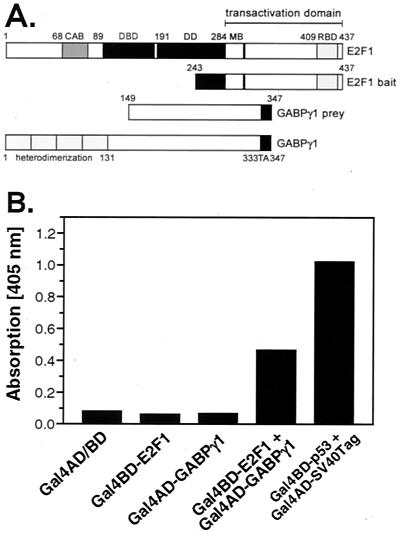

The yeast two-hybrid system was employed for the identification of proteins that might play a role as cofactors for E2F1 in cardiac cells. Carboxy-terminal amino acid residues 243 to 437 of human E2F1 were fused in frame to the Gal4 DNA-binding domain (Gal4BD) of pAS2-1 (Fig. 1A). Important for a meaningful screen for interacting proteins, this E2F1 construct does not activate HIS3-β-galactosidase expression in the yeast strain S. cerevisiae Y190 by itself. Screening of a human adult heart cDNA delivered a variety of E2F1-interacting factors. From 7 × 106 transformants, the coding sequence of one such clone was GABPγ1. The rescued GABPγ1 prey plasmid isolated in the two-hybrid screen comprised the carboxy-terminal amino acids 149 to 347 and thus lacked the four ankyrin repeat motifs (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

E2F1 and GABPγ1 cooperate in a Gal4-based yeast two-hybrid system. (A) Schematic primary amino acid sequence of the E2F1 bait and GABPγ1 prey. Abbreviations: CAB, cyclin A/cdk2-binding domain; DBD, DNA-binding domain; DD, dimerization domain; MB, marked box; RBD, pRb-binding domain; and TA, transactivation domain. (B) The E2F1/GABPγ1 interaction reconstitutes a functional Gal4 activator leading to β-galactosidase (β-gal) expression in the yeast two-hybrid assay. E2F1 (243-437) fused to the Gal4BD domain and GABPγ1 (149-347) fused to the Gal4AD domain were cotransfected into S. cerevisiae Y190 cells. Cellular extracts were analyzed for β-galactosidase expression in a liquid assay using o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside as the substrate as decribed in Materials and Methods. One representative result of two independent experiments is shown. SV40Tag, simian virus 40 large T antigen.

In the next step, the specificity of interaction between E2F1 and GABPγ1 was proven by cotransformation of yeast cells with the rescued Gal4AD-GABPγ1 and Gal4BD-E2F1 plasmids. As shown in Fig. 1B, neither E2F1 nor GABPγ1 alone activated the Gal4 assay. Only when transfected together did the N-terminally truncated mutant proteins E2F1 and GABPγ1 cooperate in reconstitution of the Gal4 activator, leading to transcription from the β-galactosidase promoter in this assay. As a positive control, the result of interaction of Gal4BD-murine wt p53 with Gal4AD-simian virus 40 large T antigen in the liquid β-galactosidase assay is shown.

In vitro association of E2F1 and GABPγ1.

The specificity of the interaction between E2F1 and GABPγ1 was further tested with various GST-tagged E2F1 mutants (Fig. 2A) and in vitro-translated l-[35S]methionine-labeled recombinant GABP proteins. As shown in Fig. 2B, lane 1 (top panel), full-length GST-E2F1 was able to bind full-length GABPγ1. As a positive control, binding of GABPγ1 to immobilized GST-GABPα is shown in Fig. 2B, lane 9 (top panel). In contrast, no binding was observed when in vitro-translated GABPα and GABPβ1 replaced GABPγ1 in the GST pulldown assay (Fig. 2B, middle and bottom panels). In Fig. 2B, lane 8 (middle panel), GST-GABPβ1 was probed with GABPα. In Fig. 2B, lane 8 (bottom panel), GST-GABPα was incubated with GABPβ1. In conclusion, E2F1 binding appears to be restricted to GABPγ1, since GABPα and GABPβ1 failed to exhibit an interaction with E2F1 in this experimental setup.

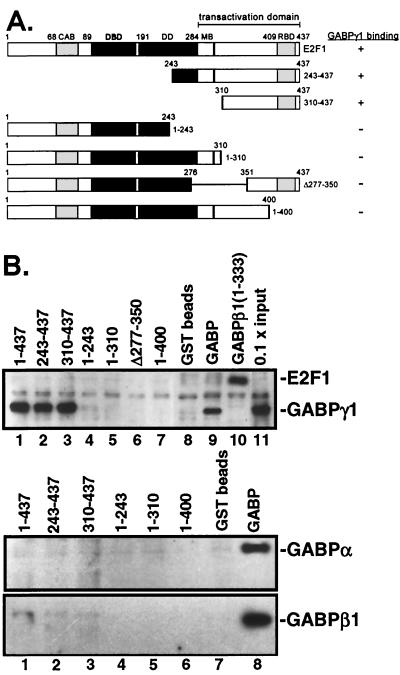

FIG. 2.

E2F1 and GABPγ1 heterodimerize in vitro. (A) Summary of various N-terminal or C-terminal truncations and deletion mutants of E2F1. (B) The GST-E2F1 fusion proteins were tested for binding to l-[35S]methionine-labeled, in vitro-translated GABPγ1. The numbers above each lane refer to the amino acid sequence contained in each GST construct. In lane 8 (middle panel), GST-GABPβ1 was reacted with in vitro-translated GABPα. In lane 8 (bottom panel), GST-GABPα was tested for binding to in vitro-translated GABPβ1. Samples were electrophoretically separated on SDS-10% PAGE and were subjected to autoradiography.

Among GST fusion proteins containing different regions of E2F1 (Fig. 2A), E2F1 (243-437) and E2F1 (310-437) but not E2F1 (1-243) and E2F1 (1-310) were able to bind GABPγ1 (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 to 5). In addition, the GST-E2F1 deletion mutant E2F1 (Δ277-350), which partially lacked overlapping regions of the marked box region and transactivation domain, and the C-terminal truncated mutant E2F1 (1-400), which was devoid of the pRb binding domain, failed to show significant binding to GABPγ1 (Fig. 2B, lanes 6 and 7, top panel). These data suggest that the sequence comprising C-terminal amino acid residues 310 to 437 of E2F1 (encompassing the transactivation and pRb binding domain) contains the GABPγ1 interaction surface.

Since amino acids 1 to 332 of GABPγ1 and GABPβ1 are almost identical, we hypothesized that differences in the C terminus of GABPγ1 (333-347) contribute specificity to the E2F1/GABPγ1 interaction (37, 41). To address the question of how such a short peptide might confer selectivity in E2F binding, GST-GABPβ1 (1-332) lacking the C-terminal dimerization domain was tested to bind in vitro-translated, wild-type E2F1. As shown in Fig. 2B (top panel, lane 10) the [35S]-labeled E2F1 indeed bound to GST-GABPβ1 (1-332).

Except for amino acid residue 213, where GABPβ1 carries an additional valine, GABPγ1 (1-332) shares an identical amino acid sequence with the corresponding GABPγ1 protein. GABPγ1 has only 15 additional C-terminal amino acids as opposed to mutant GABPβ1 (1-332). The C-terminal region 334-383 of GABPβ1 is reportedly necessary for transactivation activity and formation of GABPβ1 homodimers (37). In contrast, GABPγ1 lacks a comparable functional domain (38). Our data provide experimental evidence but do not conclusively prove that the homodimerization domain in GABPβ1 interferes with E2F1 binding.

GABPγ1 interacts specifically with E2F1 and not with other E2F family members.

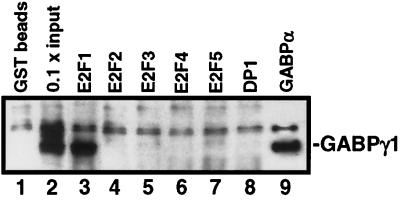

In the next set of experiments the binding of GABPγ1 to other E2F family members was analyzed. GST-E2F fusion proteins were immobilized on glutathione Sepharose beads and incubated with in vitro-translated [35S]-labeled GABPγ1. GST-DP1 (as a negative control) (Fig. 3, lane 8) and GST-GABPα (as a positive control) (Fig. 3, lane 9) were included in the binding reactions. In vitro-translated GABPγ1 was pulled down by GST-GABPα and gave rise to a band of approximately 47 kDa, indicative for a sufficient amount of GABPγ1 protein input in the binding reaction mixtures (Fig. 3, lane 9). Importantly, only GST-E2F1 and neither of the other E2F family members nor DP1 fused to GST pulled down radiolabeled GABPγ1 protein under these experimental conditions (Fig. 3, lanes 4 to 7).

FIG. 3.

GABPγ1 binds exclusively to E2F1 but not to other E2F family members in vitro. The GST-E2F fusion proteins were incubated with l-[35S]methionine-labeled in vitro-translated GABPγ1 (lanes 1 to 7). As negative control, GST-DP1 was reacted with in vitro-translated GABPγ1 (lane 8). As positive control, GST-GABPα was tested for binding to in vitro-translated GABPγ1 (lane 9). Binding reactions and detection were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

E2F1 and GABPγ1 interact in vivo.

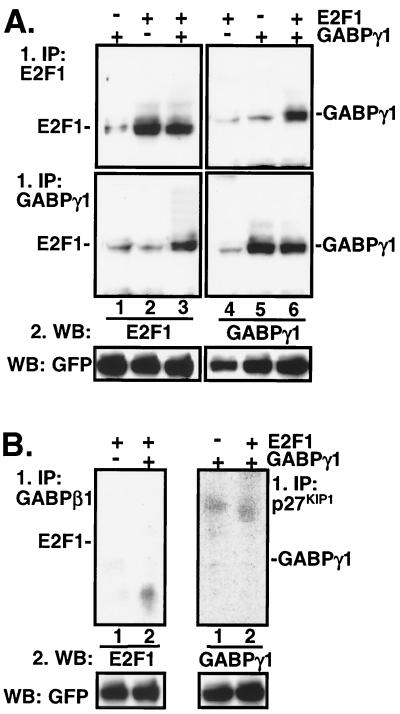

Experimental evidence for an in vivo interaction between GABPγ1 and E2F1 was obtained by coimmunoprecipitation of cellular extracts prepared from transiently transfected Cos-7 cells overexpressing E2F1 and GABPγ1. In Fig. 4A and B, E2F1/GABPγ1 immunoprecipitations were carried out using antibodies as indicated on the left, whereas Western blots were probed with antibodies as indicated on the bottom. Polyclonal antibody to E2F1 specifically precipitated E2F1 from Cos-7 cells transfected with E2F1 expression plasmid, whereas a weak signal was detectable when the same sample was probed with antisera to GABPγ1 (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 and 4). This result was further confirmed in the reciprocal experimental setup, where anti-GABPγ1 immunoprecipitates from GABPγ1-transfected Cos-7 cells reacted with anti-GABPγ1 but not anti-E2F1 antibody in the Western blot (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 and 5). Incubation of extracts derived from E2F1/GABPγ1-cotransfected cells with an antibody to E2F1 immunoprecipitated GABPγ1 (Fig. 4A, top panel, lane 6.) In the reciprocal experiment, immunoprecipitation with an antibody to GABPγ1 specifically pulled down E2F1 (Fig. 4A, bottom panel, lane 3.). Importantly, in immunoprecipitations carried out with antibodies to GABPβ1 or p27KIP1, we did not detect E2F1 and GABPγ1 in Western blots (Fig. 4B). In summary, the coimmunoprecipitation studies of ectopically expressed proteins provided conclusive experimental evidence for an in vivo interaction between GABPγ1 and E2F1.

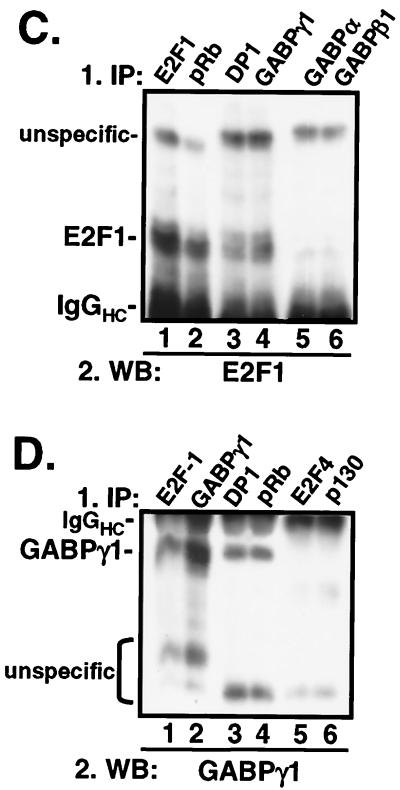

FIG. 4.

In vivo interaction between E2F1 and GABPγ1. (A and B) Exponentially growing Cos-7 cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids carrying full-length human cDNAs as indicated by the upper panel. Total cellular extracts were incubated with specifc antibodies to E2F1, GABPγ1, GABPβ, or p27KIP1 as indicated. Samples were electrophoretically separated and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Western blot (WB) detection was performed by incubation of membranes with anti-E2F1 or anti-GABPγ1, as indicated on the bottom, or anti-GFP antibodies (for equivalent loading) and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody to rabbit immunoglobulins using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham). IP, immunoprecipitation. (C and D) Association of E2F1 and GABPγ1 in cardiomyocytes. Total cellular extracts (500 μg) from unstimulated, isolated cardiomyocytes were immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies as indicated (top). Immobilized immunocomplexes were subjected to secondary immunoprecipitations using the indicated antibodies (top) as described in Materials and Methods. Western blot detection was done with antibodies indicated on the bottom. (E) E2F1/GABPγ1 complexes bind DNA. Saos-2 cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids expressing E2F1, DP1, GABPγ1, or GABPβ1 as indicated on the top. Cellular extracts were tested for binding to a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide containing the E2F consensus site as described in Materials and Methods. Five micrograms of total protein from extracts of transfected cells was tested. The specificity of binding was assessed by the addition of 1.0 μg of antibody to the binding mixture (lanes 6 to 10). mt, mutant.

Endogenous E2F1 and GABPγ1 are associated in cardiomyocytes.

Cardiomyocyte extracts were analyzed for the assoziation of endogenous E2F1 and GABPγ1 proteins by a two-step immunoprecipitation procedure as described under Materials and Methods. As shown in Fig. 4C, E2F1 was detectable in anti-GABPγ1 and anti-E2F1/DP1 immunoprecipitates. The association of endogenous E2F1/GABPγ1 proteins was further corroborated in the reciprocal experiment, where GABPγ1 was cosedimented in anti-E2F1 and anti-GABPγ1/DP1 immunoprecipitations (Fig. 4D). In contrast, antibodies specific to GABPα and -β1 failed to pull down E2F1 (Fig. 4C, lanes 5 and 6), whereas anti-E2F4 or anti-p130 immunoprecipitates did not contain GABPγ1 (Fig. 4D, lanes 5 and 6) in negative control immunoprecipitation experiments. In the same set of experiments, we addressed the question whether endogenous pRb is also associated with E2F1/GABPγ1. For that purpose, pRb was depleted from whole cellular extracts of isolated ventricular myocytes with specific antibodies. The anti-pRb immunocomplexes contained significant amounts of E2F1 (Fig. 4C, lane 2) and GABPγ1 (Fig. 4D, lane 4). In summary, our data provide substantial experimental evidence that GABPγ1 and E2F1 associate in cardiomyocytes in vivo.

E2F1 and GABPγ1 complexes bind DNA.

To determine whether E2F1/GABPγ1 complexes exhibit DNA-binding activity in vivo, Saos-2 cells were transfected with E2F1, DP1, GABPγ1, and GABPβ1 expression plasmids and gel mobility shift assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Examination of functional DNA-binding activity in extracts from these cells showed that E2F1 and DP1 proteins bound to the consensus E2F DNA-binding site in E2F1/DP1 cotransfections (Fig. 4E, lane 3). Coexpression of GABPγ1 or GABPβ did not interfere with E2F DNA-binding activity (Fig. 4E, lanes 4 and 5). We repeatedly found no modification of the migration velocity of the E2F1 band in the presence of exogenous GABPγ1, which most likely is due to the excess protein levels of endogenous GABPγ1 compared to E2F1 in exponentially growing Saos-2 cells. Addition of a polyclonal antibody against E2F1 to the DNA-binding reaction of cellular extracts from E2F1/DP1 cotransfections produced a supershifted complex with a lower electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 4E, lane 6). Importantly, addition of antibodies against E2F1 (Fig. 4E, lane 7) or GABPγ1 (Fig. 4E, lane 8) gave rise to a further supershift in E2F1/DP1/GABPγ1 cotransfections. Addition of an anti-GABPβ antibody did not exert a decrease in electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 4E, lane 9). Our data show that GABPγ1 participates in E2F1 DNA-binding activity in vivo.

Cooperation of E2F1 and GABPγ1 leads to enhanced E2F-dependent transcriptional activation.

To elucidate whether the observed interaction of E2F1 and GABPγ1 has a functional role in gene expression, the effect of GABPγ1 on E2F1-mediated gene transcription was investigated. Since E2F1-dependent transcriptional activation is under negative control of pRb by binding to the activation domain of E2F, Saos-2 cells were employed expressing a carboxy-terminally truncated, physiologically inactive pRb protein (14). E2F-dependent transcriptional activation was analyzed with a replication-dependent S-phase-specific human histone H2A.1 luciferase reporter construct. The plasmid pl-H2A-68 contains the luciferase cDNA under the control of an upstream E2F consensus element which is mutated in pl-H2A-68∗ (30). Exponentially growing Saos-2 cells were transiently transfected alone or in combination with E2F1, DP1, GABP, and pRb expression plasmids together with the reporter constructs, as indicated in Fig. 5A. Cotransfection of E2F1/DP1 stimulated basal pl-H2A-68 activation 5.4-fold (Fig. 5A, lane 2), as opposed to 0.1-fold activation when pl-H2A-68∗ was transfected carrying the mutated E2F-binding site (Fig. 5A, lane 11). Transcription from E2F-dependent promoters is suppressed by pRb, and this was previously shown for pl-H2A-68 (30). As expected, E2F1-dependent luciferase activity of the pl-H2A-68 reporter was attenuated to 1.7-fold by pRb overexpression (Fig. 5A, lane 14). Surprisingly, cotransfection of GABPγ1 with E2F1/DP1 led to a 2.6-fold increase in luciferase activity as compared to E2F1/DP1 (Fig. 5, lane 3). The modulation of E2F1 transactivation capacity by GABPγ1 did not require simultaneous expression of DP1 (Fig. 5A, lane 4). Ectopic expression of pRb resulted in a 93% repression of the pl-H2A-68 reporter in E2F1/DP1/GABPγ1 cotransfections (Fig. 5A, lane 13). The promoting impact on E2F-regulated promoter activity by GABPγ1 suggests that the association of GABPγ1 and E2F1 has a synergistic effect on E2F1 transactivation capacity. Taken together, our results imply that GABPγ1 participates in the regulation of E2F1-dependent gene transcription.

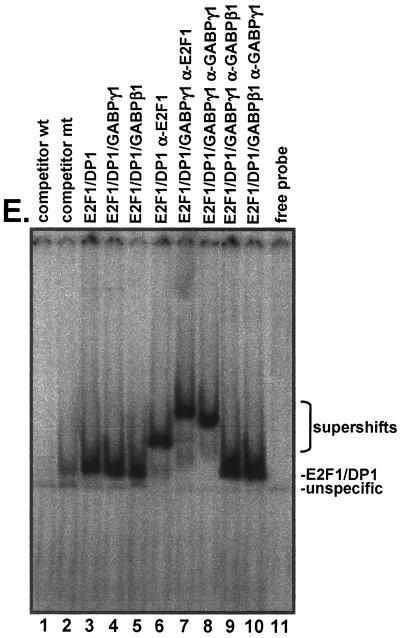

FIG. 5.

(A) E2F1 and GABPγ1 cooperate in E2F-dependent transcriptional transactivation of an S-phase-specific histone H2A.1-Luc promoter construct. (B) The ratio of E2F1 and GABPγ1 influences E2F1-dependent transcriptional activation. (C) The transactivation domain of E2F1 is required for the modulation of E2F1 transcriptional activity by GABPγ1. In E2F1 (1-374) the transactivation domain has been deleted. The point mutant E2F1 (E132) carries a mutation within the DNA-binding domain. In E2F1 Δ24 the N-terminally located cyclin A-binding site has been deleted. Exponentially growing Saos-2 cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids and reporter constructs as described in Materials and Methods. pI-H2A-68 carries a wt E2F consensus DNA-binding site, whereas this site is mutated in pl-H2A-68∗. Luciferase activity was determined from whole-cell extracts containing 60 μg of total protein. Fold activation of luciferase activity was corrected for β-galactosidase expression as described in Materials and Methods. Mean values and standard deviations of three independent experiments are presented.

To analyze the ratio of E2F1 to GABPγ1 in the control of E2F-dependent transcription from pl-H2A-68, various amounts of GABPγ1 and E2F1 expression plasmids were cotransfected into Saos-2 cells along with constant amounts of DP1 and pl-H2A-68. When decreasing amounts of GABPγ1 were transfected with constant amounts of E2F1 expression plasmids, transactivation values were found to decrease (Fig. 5B, lanes 1 to 4). When the amount of GABPγ1 plasmid was reduced to 60%, the luciferase activity was reduced to 63% (Fig. 5B, lanes 1 and 2). Conversely, when decreasing amounts of E2F1 were transfected with constant amounts of GABPγ1 expression plasmid, the promoter activity was also reduced in a dosage-dependent manner (Fig. 5B, lanes 6 to 8). Collectively, these data show that E2F1-mediated transcriptional activation is controlled by a quantitative ratio of E2F1 and GABPγ1.

To further specify the impact of GABPγ1 on E2F-dependent gene transcription, three E2F1 mutants were tested in transient-transfection assays. In mutant E2F1 (1-374) the transactivation domain has been deleted (14, 31). E2F1 (E132) carries a point mutation within the DNA-binding domain and thus fails to bind DNA (14, 31). Both E2F1 (1-374) and E2F1 (E132) are transcriptionally inactive mutants which reportedly are unable to transactivate E2F-dependent promoter constructs (14, 31). In E2F1 Δ24 the N-terminally located cyclin A-binding site has been deleted (22, 23). In contrast to E2F1 (E132) and E2F1 (1-374), E2F1 Δ24 was shown to be capable of activating E2F-dependent promoters to approximately the same extent as wt E2F1 (31). As expected, cotransfection of E2F1 (1-374) and GABPγ1 did not induce H2A gene transcription, showing that the transactivation domain of E2F1 is required for GABPγ1 to superstimulate this reporter (Fig. 5C, lanes 4 and 5). In addition, ectopic E2F1 (E132)/GABPγ1 did not induce luciferase reporter activity over a basal level (Fig. 5C, lanes 6 and 7). Therefore, a functional E2F1 DNA-binding domain is required for GABPγ1 to exert its facilitating effect on E2F-dependent transactivation. In contrast, the cyclin A-binding domain of E2F1 is obviously dispensable for the activation of this promoter, as cotransfection of E2F1 Δ24/GABPγ1 led to an increase in luciferase activity comparable to that of wt E2F1/GABPγ1 (Fig. 5C, lanes 1 to 3, 8 and 9).

Interaction of E2F1 and GABPγ1 represses E2F1-dependent apoptosis.

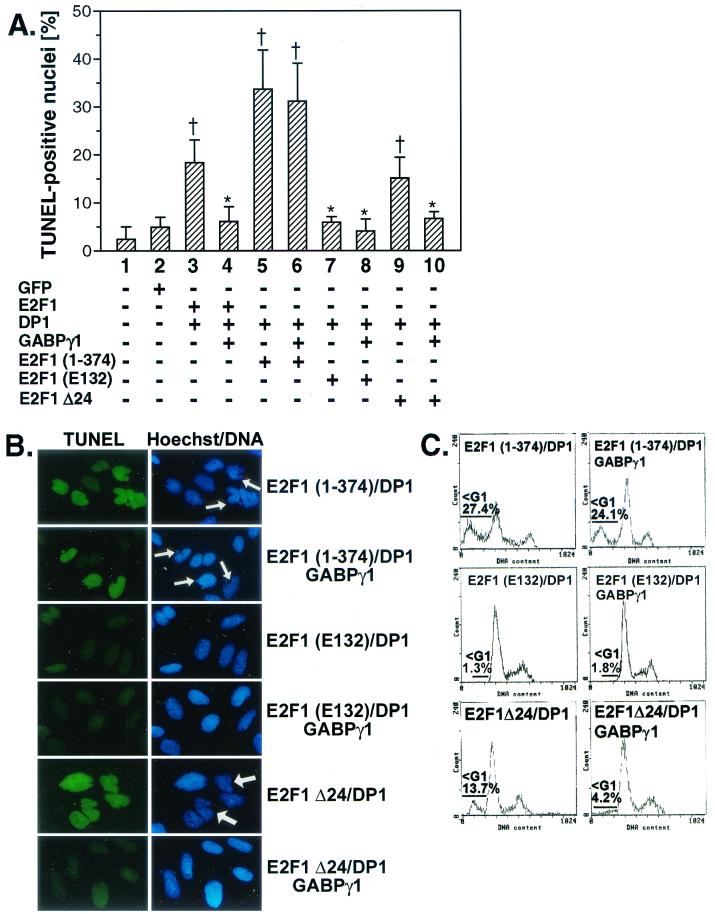

To study the effect of GABPγ1 on the proapoptotic activity of E2F1, exponentially growing Saos-2 cells grown on coverslips were transiently transfected with E2F1 alone or in combination with GABPγ1 or DP1 expression plasmids. At 24 h postinfection, marked apoptosis, as demonstrated by TUNEL assay, Hoechst staining for integrity of nuclei (Fig. 6A and B), and FACS analysis (Fig. 6C), could be observed in cells overexpressing E2F1 (4.1-fold induction versus GFP-infected cells) or E2F1/DP1 (3.7-fold induction versus GFP transfections as evaluated by TUNEL) (Fig. 6A and B). In contrast, cotransfection of E2F1/GABPγ1 and E2F1/DP1/GABPγ1 led to a significantly reduced rate of TUNEL-positive apoptotic Saos-2 cells (1.1- and 1.4-fold induction versus E2F1 alone), which was corroborated by FACS analysis (Fig. 6C).

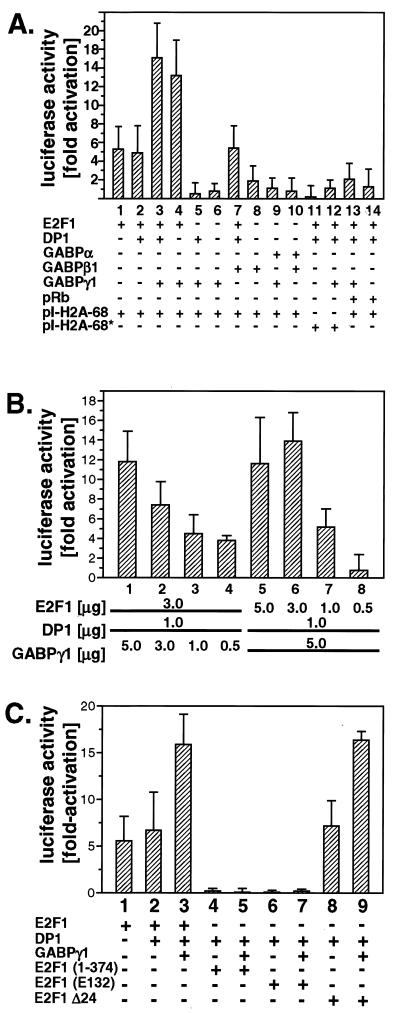

FIG. 6.

Ectopic expression of E2F1 and GABPγ1 leads to repression of E2F1-dependent apoptosis. (A and B) Saos-2 cells grown on coverslips were either left untreated or cotransfected in various combinations with CMV-driven E2F1, DP1, GABPγ1, or GABPβ1 expression plasmids as described in Materials and Methods. At 24 h after transfection, a direct TUNEL immunofluorescence assay for the detection of apoptotic cell death was performed. Immunocytochemical detection of apoptotic nuclei was done using the TUNEL assay (fluorescein isothiocyanate, green). Fragmented nuclei were identified by Hoechst 33258 staining (DNA, blue) and are indicated by white arrows. For the quantitative analyses 200 nuclei were counted in random fields (values are mean ± standard deviations, n = 3; †, P < 0.05 versus mock-infected cells; ∗, P < 0.05 versus E2F1 alone in cells overexpressing E2F1). (C) For quantitative analysis of apoptotic cells by flow cytometry, Saos-2 cells were transfected with expression plasmids as described in Materials and Methods. Only GFP-positive cells were gated and analyzed for cell cycle distribution. The percentage of apoptotic hypodiploid cells in sub-G1 was determined with the indicated gates and EPICS software (Coulter). One result of at least two independent experiments is shown.

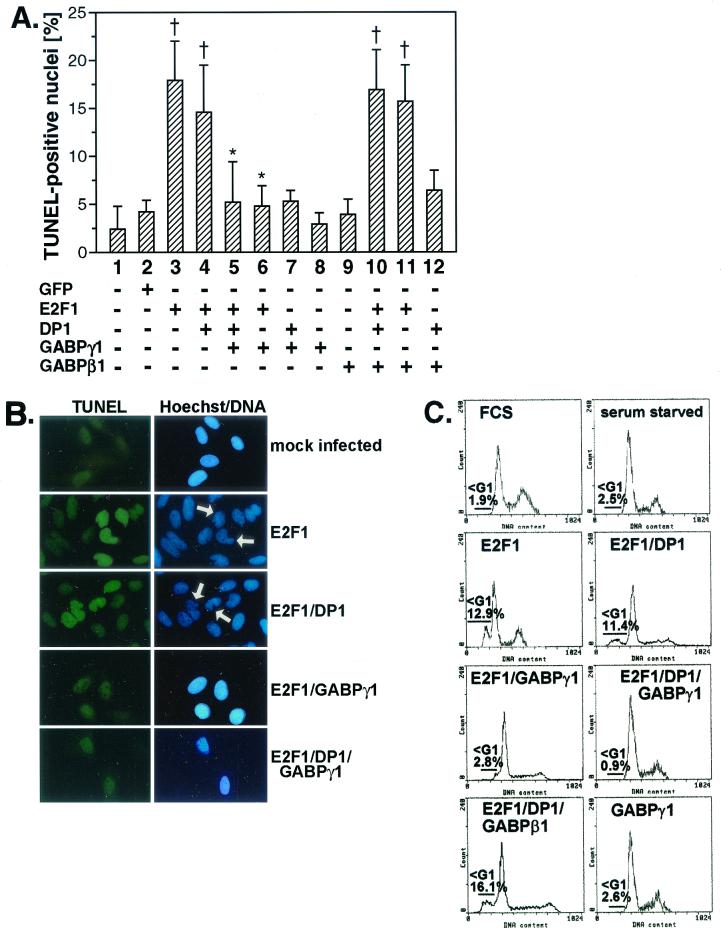

To analyze the importance of E2F1 DNA-binding and transactivation activity regarding an antiapoptotic function of GABPγ1, we tested the transactivation-defective mutants E2F1 (1-374) and E2F1 (E132) (Fig. 7). E2F1 (1-374) induced apoptosis to a significantly higher degree than did wt E2F1. As opposed to the case for wt E2F1, E2F1 (1-374)-mediated apoptosis was not susceptible to repression by cotransfected GABPγ1 as analyzed by TUNEL assay (Fig. 7A and B) and determination of the number of cells with a hypodiploid DNA content residing in sub-G1 by flow cytometry (Fig. 7C). Since the E2F1 transactivation domain encompasses the GABPγ1 binding site, the loss of the antagonistic effect of GABPγ1 on apoptosis induced by the mutant E2F1 (1-374) is not surprising. Moreover, coexpression of GABPγ1 led to the inhibition of E2F1 Δ24-triggered apoptosis, implying that the cyclin A-binding site of E2F1 is not required for this function of GABPγ1 (Fig. 7A). The DNA-binding defective mutant E2F1 (E132) failed to exhibit any proapoptotic activity in our experimental setup (Fig. 7A), which is in accordance with previous studies (14, 31). Collectively, these data indicate that an intact E2F1 transactivation domain is dispensable for the proapoptotic effect of E2F1, while it is required for GABPγ1 to suppress E2F-dependent apoptosis.

FIG. 7.

Inhibition of E2F1-dependent apoptosis through GABPγ1 requires the E2F1 transactivation domain. Saos-2 cells were transfected in various combinations with wt E2F1, E2F1 (1-374), E2F1 (E132), E2F1 Δ24, DP1, and GABPγ1 expression plasmids as described in Materials and Methods. Saos-2 cells were transfected with expression plasmids as indicated and were prepared for immunocytochemical detection of apoptosis by TUNEL assay (A and B) and FACS analysis (C) as described for Fig. 6 (values are mean ± standard deviations, n = 3; †, P < 0.05 versus mock-infected cells, ∗, P < 0.05 versus E2F1 alone in cells overexpressing E2F1).

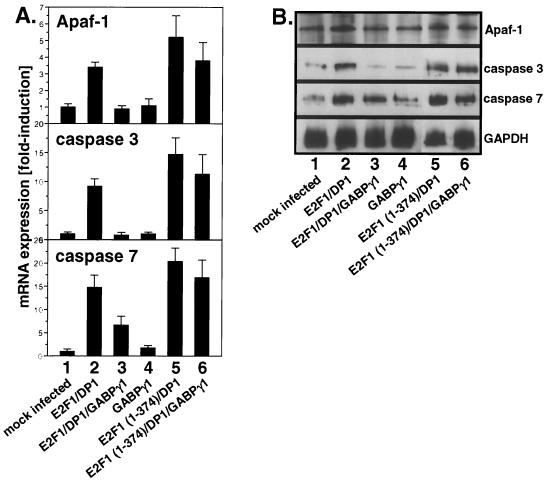

GABPγ1 inhibition of E2F1-dependent apoptosis involves repression of proapoptotic gene transcription.

To analyze whether the inhibition of E2F1-dependent apoptosis by GABPγ1 involves transcriptional repression of E2F target genes, Northern blot experiments were performed employing full-length cDNAs to Apaf-1 and caspases 3 and 7, which were recently identified to be directly regulated by E2F1 (28). The mRNA levels of Apaf-1 and caspases 3 and 7 were significantly increased in apoptotic Saos-2 cells overexpressing E2F1/DP1 (Fig. 8A and B, lane 2). Importantly, coexpression of GABPγ1 decreased the transcript levels of all three proapoptotic factors close to control levels (Fig. 8A and B, lane 3). These data show that the inhibitory effect of GABPγ1 on E2F1-dependent apoptosis involves the downregulation of E2F1-mediated expression of proapoptotic genes. However, transient expression of E2F1 (1-374) lacking the transactivation domain also resulted in significantly increased mRNA levels of Apaf-1 and caspases 3 and 7. Moreover, the increase in transcript levels observed in E2F1 (1-374) transfections remained unaffected by coexpression of GABPγ1 (Fig. 8A and B, lanes 5 and 6). Taken together, E2F1-mediated gene transcription of these proapoptotic factors does not require its transactivation domain. Although the precise mechanism of E2F1-dependent regulation of gene expression during the execution of apoptosis remains to be determined, our data imply that the inhibitory effect of GABPγ1 on E2F1-dependent cell death is elicited by mechanisms other than the modulation of the transactivation capacity of E2F1.

FIG. 8.

Inhibition of E2F-dependent apoptosis by GABPγ1 involves repression of gene transcription. Saos-2 cells were transiently transfected with CMV-driven wt E2F1, E2F1 (1-374), DP1, and GABPγ1 expression plasmids. Total RNA was extracted at 24 h after infection. The blot was probed with full-length cDNAs to Apaf-1 and caspases 3 and 7, and mRNA levels were normalized using GAPDH expression as described in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

In this report we show that the ETS-related transcription factor GABPγ1 interacts with E2F1 in vitro and in vivo. The interaction surface of E2F1 to GABPγ1 was mapped to the transactivation domain of E2F1. GABPγ1 stimulates E2F1-dependent transcriptional activity and suppresses E2F1-mediated apoptosis. The latter involves the repression of proapoptotic genes by mechanisms other than the inhibition of the transactivation capacity of E2F1.

GABP is a heteromeric DNA-binding protein which consists of GABPα, an ETS family member, and an ankyrin repeat-containing protein (GABPβ1 or GABPγ1) (38). GABPα and GABPβ can form a heterotetrameric α2β2 complex which efficiently stimulates gene transcription in vitro and in vivo. In contrast, association of GABPα/GABPγ1 is devoid of any transcriptional activation potential in vivo (38). GABPβ1 exclusively requires association with GABPα for transcriptional transactivation. However, GABPγ1 reportedly binds to ETS family proteins other than GABPα (38). GABP is involved in transcriptional regulation of the adenovirus early region 4 gene, herpex simplex virus immediate early gene promoter, Fas and cytokine receptor in hematopoietic lineages, cytochrome c oxidase, and steroid 16a-hydroxylase protein (1, 8). Recently, transcription of the 180-kDa subunit of the DNA polymerase α was shown to be regulated by E2F, GABP, and Sp1 (15), the latter of which interacts with E2F1 in a cell cycle-regulated manner (18). A general requirement for GABP transcription factors to selectively induce gene transcription is cooperation with protein partners from unrelated families (9). Therefore, transcription complexes often contain proteins from different families, ensuring controlled regulation of gene transcription during growth and development.

In our study, GABPγ1 significantly augmented E2F1-dependent gene transcription in transient-transfection studies employing Saos-2 cells. Coexpression of pRb gave rise to an inhibition of pl-H2A-68 reporter stimulation by E2F1/GABPγ1 (Fig. 5). The ability of pocket proteins to specifically interfere with the E2F-dependent transactivation of this particular promoter was analyzed extensively in vitro (30). Therefore, our data suggest that pRb suppresses physiologically relevant E2F1/GABPγ1 complexes.

Recent reports demonstrated that E2F1-dependent apoptosis requires its DNA-binding domain but not the transactivation domain, which in contrast is necessary for S-phase entry (14, 31). The E2F1 mutant (1-374) lacking most of the transactivation domain was previously shown to be even more effective in inducing apoptosis in Saos-2 cells than was wt E2F1 (14, 31). Our study shows that GABPγ1 failed to inhibit apoptosis induced by mutant E2F1 (1-374), as opposed to full-length E2F1 or E2F1 Δ24, the latter of which in this regard was indistinguishable from wt E2F1 (Fig. 6 and 7). The fact that GABPγ1 did not counteract E2F1 (1-374)-mediated apoptosis is due to the absence of the transactivation domain in E2F1 (1-374), which was identified as the interaction surface for GABPγ1 in vitro (Fig. 2). In addition to the truncated mutant E2F1 (1-374) analyzed in this study, pRb-binding-defective E2F1 deletion mutants (e.g., E2F1 Δ406-415) were demonstrated to induce apoptosis to the same extent as wt E2F1 (14). In our study, we did not use these E2F1 mutants since a C-terminally truncated E2F1 (1-400), which is devoid of the pRb-binding domain, did not bind to GABPγ1 in GST pulldown assays (Fig. 2B).

As reported previously, the association of E2F1 with its heterologous dimerization partner DP1 accelerates cellular death (13). Simultaneous expression of MDM2 and E2F1/DP1 also leads to suppression of apoptosis in Saos-2 cells (25). Interestingly, the antiapoptotic effect of MDM2 on E2F1-mediated apoptosis was dependent on the direct interaction of MDM2 with the DP1 unit of E2F1/DP1 heterodimers (25, 27). Although E2F1 and E2F1/DP1 induced apoptosis to a comparable degree in this study, MDM2 was capable only of inhibiting E2F1-mediated cell death in the presence of DP1 (25). In contrast to MDM2, GABPγ1 does not interact with DP1 directly as demonstrated by in vitro binding studies (Fig. 3). In addition, our study revealed that cotransfection of GABPγ1 also led to suppression of E2F1-dependent apoptosis even when DP1 was not included in E2F1 transfections (Fig. 6A). We infer from these data that GABPγ1 and MDM2 might control cellular E2F1 activity by distinct mechanisms. It appears tentative to speculate that GABPγ1 acts as a coactivator directing another unknown factor(s) to E2F transcription factor complexes, which in turn might then activate antiapoptotic processes.

To extend our results based on immunocytochemical detection of cell death (TUNEL and Hoechst staining) or flow cytometry analysis of cells with hypodiploid DNA content (Fig. 6 and 7), the impact of GABPγ1 on E2F-regulated gene transcription during E2F1-induced apoptosis was investigated. Northern blot analysis revealed that ectopic expression of E2F1 led to an increase in mRNA transcripts of E2F-regulated proapoptotic factors (Apaf-1 and caspases 3 and 7) involved in the execution of cell death (Fig. 8). Cotransfection of GABPγ1 diminished the increase in transcript levels of all of these factors tested, suggesting that the inhibitory effect of GABPγ1 on E2F1-induced apoptosis involves the downregulation of E2F-regulated genes. Importantly, in light of the dispensability of the E2F1 transactivation domain for both E2F1-dependent induction of proapoptotic genes and execution of apoptosis, our data imply that GABPγ1 counteracts E2F1-induced apoptosis by mechanisms other than the modulation of its transactivation capacity. In this context, a recent study by Philips et al. (32) showed that E2F1 induces apoptosis in Saos-2 cells by downregulation of TRAF2 expression, which prevents the activation of the antiapoptotic factors NF-κB and Jnk. Since E2F1-induced gene transcription of proapoptotic factors could involve repression of antiapoptotic complexes, a phenomenon attributed to E2F1-dependent gene transcription, one such mechanism could be GABPγ1-mediated derepression of such antiapoptotic complexes (42).

GABP was shown to be involved in differentiation of skeletal muscle cells (36), where elevation of pRb expression is a key event (10, 29). Upon induction of myoblast differentiation, transcriptional activation of the pRb gene was strongly activated by interaction of GABP with bcl-3 (40). Therefore, regulation of E2F1-dependent gene transcription by GABPγ1 might also be relevant for differentiation or maladaptive growth of heart muscle cells.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to H. Handa (Tokyo Institute of Technology, Yokohama, Japan), who generously provided GABP cDNAs and antibodies to GABP, and to K. Vousden, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, Md., for her kind gift of mutant E2F1 plasmids.

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid from the Max Delbrück Center (M.L. and R.V.H.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Batchelor, A. H., D. E. Piper, F. C. de la Brousse, S. L. McKnight, and C. Wolberger. 1998. The structure of GABPalpha/beta: an ETS domain-ankyrin repeat heterodimer bound to DNA. Science 279:1037-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brehm, A., E. A. Miska, D. J. McCance, J. L. Reid, A. J. Bannister, and T. Kouzarides. 1998. Retinoblastoma protein recruits histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nature 391:597-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, V. D., R. A. Phillips, and B. L. Gallie. 1999. Cumulative effect of phosphorylation of pRB on regulation of E2F activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:3246-3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, X., and R. Prywes. 1999. Serum-induced expression of the cdc25A gene by relief of E2F-mediated repression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:4695-4702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clerk, A., A. Michael, and P. H. Sugden. 1998. Stimulation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes by the G protein-coupled receptor agonists, endothelin-1 and phenylephrine: a role in cardiac myocyte hypertrophy? J. Cell Biol. 142:523-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de la Brousse, F. C., E. H. Birkenmeier, D. S. King, L. B. Rowe, and S. L. McKnight. 1994. Molecular and genetic characterization of GABP beta. Genes Dev. 8:1853-1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyson, N. 1998. The regulation of E2F by pRB-family proteins. Genes Dev. 12:2245-2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flory, E., A. Hoffmeyer, U. Smola, U. R. Rapp, and J. T. Bruder. 1996. Raf-1 kinase targets GA-binding protein in transcriptional regulation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 promoter. J. Virol. 70:2260-2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graves, B. J. 1998. Inner workings of a transcription factor partnership. Science 279:1000-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu, W., J. W. Schneider, G. Condorelli, S. Kaushal, V. Mahdavi, and B. Nadal-Ginard. 1993. Interaction of myogenic factors and the retinoblastoma protein mediates muscle cell commitment and differentiation. Cell 72:309-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helin, K., E. Harlow, and A. Fattaey. 1993. Inhibition of E2F-1 transactivation by direct binding of the retinoblastoma protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:6501-6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helin, K., C. L. Wu, A. R. Fattaey, J. A. Lees, B. D. Dynlacht, C. Ngwu, and E. Harlow. 1993. Heterodimerization of the transcription factors E2F-1 and DP-1 leads to cooperative trans-activation. Genes Dev. 7:1850-1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiebert, S. W., G. Packham, D. K. Strom, R. Haffner, M. Oren, G. Zambetti, and J. L. Cleveland. 1995. E2F-1:DP-1 induces p53 and overrides survival factors to trigger apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:6864-6874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsieh, J. K., S. Fredersdorf, T. Kouzarides, K. Martin, and X. Lu. 1997. E2F1-induced apoptosis requires DNA binding but not transactivation and is inhibited by the retinoblastoma protein through direct interaction. Genes Dev. 11:1840-1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Izumi, M., M. Yokoi, N. S. Nishikawa, H. Miyazawa, A. Sugino, M. Yamagishi, M. Yamaguchi, A. Matsukage, F. Yatagai, and F. Hanaoka. 2000. Transcription of the catalytic 180-kDa subunit gene of mouse DNA polymerase alpha is controlled by E2F, an Ets-related transcription factor, and Sp1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1492:341-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson, D. G., K. Ohtani, and J. R. Nevins. 1994. Autoregulatory control of E2F1 expression in response to positive and negative regulators of cell cycle progression. Genes Dev. 8:1514-1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson, D. G., J. K. Schwarz, W. D. Cress, and J. R. Nevins. 1993. Expression of transcription factor E2F1 induces quiescent cells to enter S phase. Nature 365:349-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karlseder, J., H. Rotheneder, and E. Wintersberger. 1996. Interaction of Sp1 with the growth- and cell cycle-regulated transcription factor E2F. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1659-1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirshenbaum, L. A., M. Abdellatif, S. Chakraborty, and M. D. Schneider. 1996. Human E2F-1 reactivates cell cycle progression in ventricular myocytes and represses cardiac gene transcription. Dev. Biol. 179:402-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirshenbaum, L. A., and M. D. Schneider. 1995. Adenovirus E1A represses cardiac gene transcription and reactivates DNA synthesis in ventricular myocytes, via alternative pocket protein- and p300-binding domains. J. Biol. Chem. 270:7791-7794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kowalik, T. F., J. DeGregori, J. K. Schwarz, and J. R. Nevins. 1995. E2F1 overexpression in quiescent fibroblasts leads to induction of cellular DNA synthesis and apoptosis. J. Virol. 69:2491-2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krek, W., M. E. Ewen, S. Shirodkar, Z. Arany, W. G. Kaelin, Jr., and D. M. Livingston. 1994. Negative regulation of the growth-promoting transcription factor E2F-1 by a stably bound cyclin A-dependent protein kinase. Cell 78:161-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krek, W., G. Xu, and D. M. Livingston. 1995. Cyclin A-kinase regulation of E2F-1 DNA binding function underlies suppression of an S phase checkpoint. Cell 83:1149-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazou, A., P. H. Sugden, and A. Clerk. 1998. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (p38-MAPKs, SAPKs/JNKs and ERKs) by the G-protein-coupled receptor agonist phenylephrine in the perfused rat heart. Biochem. J. 332:459-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loughran, Ö., and N. B. La Thangue. 2000. Apoptotic and growth-promoting activity of E2F modulated by MDM2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:2186-2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magnaghi-Jaulin, L., R. Groisman, I. Naguibneva, P. Robin, S. Lorain, J. P.Le Villain, F. Troalen, D. Trouche, and A. Harel-Bellan. 1998. Retinoblastoma protein represses transcription by recruiting a histone deacetylase. Nature 391:601-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin, K., D. Trouche, C. Hagemeier, T. S. Sorenson, N. B. La Thangue, and T. Kouzarides. 1995. Stimulation of E2F1/DP1 transcriptional activity by MDM2 oncoprotein. Nature 375:691-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moroni, M. C., E. S. Hickman, E. L. Denchi, G. Caprara, E. Colli, F. Cecconi, H. Muller, and K. Helin. 2001. Apaf-1 is a transcriptional target for E2F and p53. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:552-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novitch, B. G., G. J. Mulligan, T. Jacks, and A. B. Lassar. 1996. Skeletal muscle cells lacking the retinoblastoma protein display defects in muscle gene expression and accumulate in S and G2 phases of the cell cycle. J. Cell Biol. 135:441-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oswald, F., T. Dobner, and M. Lipp. 1996. The E2F transcription factor activates a replication-dependent human H2A gene in early S phase of the cell cycle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1889-1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips, A. C., S. Bates, K. M. Ryan, K. Helin, and K. H. Vousden. 1997. Induction of DNA synthesis and apoptosis are separable functions of E2F-1. Genes Dev. 11:1853-1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phillips, A. C., M. K. Ernst, S. Bates, N. R. Rice, and K. H. Vousden. 1999. E2F-1 potentiates cell death by blocking antiapoptotic signaling pathways. Mol. Cell 4:771-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qin, X. Q., D. M. Livingston, M. Ewen, W. R. Sellers, Z. Arany, and W. G. Kaelin, Jr. 1995. The transcription factor E2F-1 is a downstream target of RB action. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:742-755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qin, X. Q., D. M. Livingston, W. G. Kaelin, Jr., and P. D. Adams. 1994. Deregulated transcription factor E2F-1 expression leads to S-phase entry and p53-mediated apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:10918-10922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross, J. F., X. Liu, and B. D. Dynlacht. 1999. Mechanism of transcriptional repression of E2F by the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein. Mol. Cell 3:195-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savoysky, E., T. Mizuno, Y. Sowa, H. Watanabe, J. Sawada, H. Nomura, Y. Ohsugi, H. Handa, and T. Sakai. 1994. The retinoblastoma binding factor 1 (RBF-1) site in RB gene promoter binds preferentially E4TF1, a member of the Ets transcription factors family. Oncogene 9:1839-1846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sawa, C., M. Goto, F. Suzuki, H. Watanabe, J. Sawada, and H. Handa. 1996. Functional domains of transcription factor hGABP beta1/E4TF1-53 required for nuclear localization and transcription activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:4954-4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sawada, J., M. Goto, C. Sawa, H. Watanabe, and H. Handa. 1994. Transcriptional activation through the tetrameric complex formation of E4TF1 subunits. EMBO J. 13:1396-1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shan, B., and W. H. Lee. 1994. Deregulated expression of E2F-1 induces S-phase entry and leads to apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:8166-8173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiio, Y., J. Sawada, H. Handa, T. Yamamoto, and J. Inoue. 1996. Activation of the retinoblastoma gene expression by Bcl-3: implication for muscle cell differentiation. Oncogene 12:1837-1845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki, F., M. Goto, C. Sawa, S. Ito, H. Watanabe, J. Sawada, and H. Handa. 1998. Functional interactions of transcription factor human GA-binding protein subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 273:29302-29308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takahashi, Y., J. B. Rayman, and B. D. Dynlacht. 2000. Analysis of promoter binding by the E2F and pRB families in vivo: distinct E2F proteins mediate activation and repression. Genes Dev. 14:804-816. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsai, K. Y., Y. Hu, K. F. Macleod, D. Crowley, L. Yamasaki, and T. Jacks. 1998. Mutation of E2f-1 suppresses apoptosis and inappropriate S phase entry and extends survival of Rb-deficient mouse embryos. Mol. Cell 2:293-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Harsdorf, R., L. Hauck, F. Mehrhof, U. Wegenka, M. C. Cardoso, and R. Dietz. 1999. E2F-1 overexpression in cardiomyocytes induces downregulation of p21CIP1 and p27KIP1 and release of active cyclin-dependent kinases in the presence of insulin-like growth factor I. Circ. Res. 85:128-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wasylyk, B., J. Hagman, and A. Gutierrez-Hartmann. 1998. Ets transcription factors: nuclear effectors of the Ras-MAP-kinase signaling pathway. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23:213-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watanabe, H., T. Imai, P. A. Sharp, and H. Handa. 1988. Identification of two transcription factors that bind to specific elements in the promoter of the adenovirus early-region 4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:1290-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watanabe, H., J. Sawada, K. Yano, K. Yamaguchi, M. Goto, and H. Handa. 1993. cDNA cloning of transcription factor E4TF1 subunits with Ets and notch motifs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:1385-1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weintraub, S. J., K. N. Chow, R. X. Luo, S. H. Zhang, S. He, and D. C. Dean. 1995. Mechanism of active transcriptional repression by the retinoblastoma protein. Nature 375:812-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu, C. L., L. R. Zukerberg, C. Ngwu, E. Harlow, and J. A. Lees. 1995. In vivo association of E2F and DP family proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:2536-2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yan, Z., J. DeGregori, R. Shohet, G. Leone, B. Stillman, J. R. Nevins, and R. S. Williams. 1998. Cdc6 is regulated by E2F and is essential for DNA replication in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3603-3608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]