Abstract

The tumor suppressor p53 eliminates cancer-prone cells via multiple mechanisms, including apoptosis. Ras elicits apoptosis in cells after protein kinase C (PKC) downregulation. However, the role of p53 in Ras-mediated apoptosis has not been fully investigated. Here, we demonstrate that mouse fibroblasts that express wild-type p53 are more susceptible to apoptosis elicited by PKC inhibition if Ras is transiently expressed or upregulated as opposed to stably expressed. In the latter case, p53 is frequently mutated. Transiently increased Ras activity induces Bax, and PKC inhibition augments this induction. Overexpression of E6 inactivates p53 and thereby suppresses both Bax induction and apoptosis. In contrast, Bax is not induced in stable ras transfectants, regardless of PKC inhibition. The data suggest that short- and long-term activation of Ras use a different mechanism(s) to initiate apoptosis. The status of p53 may contribute to such differences.

Mutations of ras genes have been detected as early events in the development of many types of tumors (7, 32). Overexpression of activated ras leads to tumorigenesis in transgenic mice and in naturally occurring human neoplasia (1, 25, 27, 48). Through interaction with its downstream effector(s), such as the Raf family members or protein kinase B (PKB)/Akt, Ras activates the MEK/mitogen-activated protein kinases and subsequently regulates the activities of transcriptional factors, such as Elk-1 and AP-1 (15, 26, 40). Ras signaling has also been linked to the cell cycle machinery via the regulation of cyclins (especially cyclin D1) and tumor suppressors (Rb and p53) (16). Recently, many studies have demonstrated that Ras is associated with augmented apoptosis (11, 17, 35, 46). However, whether the outcome of Ras signaling is cell proliferation and differentiation or apoptosis depends ultimately upon the cellular context, the presence or absence of other regulatory influences, and the persistence of the signal.

Tumor formation is a multistep process involving positive, growth-stimulatory signals which permit uncontrolled cell proliferation and negative, protective regulation that eliminates unlimited growth through the induction of an apoptotic crisis (21, 43, 49, 51, 53). These two conflicting signals often occur simultaneously during the transformation process, in which p53 has been implicated as a crucial regulator (3, 28). A functional p53, together with other cell cycle regulators, elicits the apoptotic crisis during the establishment of myc-induced immortalization or the transformation process mediated by Abelson murine leukemia virus (3, 28, 48). p53, as a transcriptional factor, also regulates the induction and function of several other genes, including Bax and p21, which participate in either p53-dependent apoptosis or growth arrest (28, 36, 37). It has been observed that mutations in both p53 and ras genes often occur in the same cancer cell (5, 8, 30, 48). In colon cancer cells, Ras mutations have been demonstrated to precede p53 mutations (30). The possible mechanism has been proposed to be one in which the Ras signaling pathway suppresses p53 during an early stage of tumor development by targeting MDM2 activity (42).

Bax is a cell death agonist with homology to the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 protein (36, 41). Mice deficient in Bax have selective hyperplasia and show resistance to certain apoptotic stimuli (36, 37). Overexpression of p53 increases Bax expression in various cell lines, and this increase correlates with the induction of apoptosis in various cell types (36, 37). Overexpression of Bcl-2 protects cells from certain types of apoptosis, including Ras-mediated cell death, and also counteracts the proapoptotic function of Bax elicited by various apoptotic stimuli (11, 36, 37, 39, 41). However, the involvement of Bax in Ras-induced cell death has not yet been fully explored.

The complex relationship between cell proliferation or differentiation and apoptosis mediated by oncogenic ras has begun to be elucidated (11, 17, 35, 46). We previously reported that mouse or human lymphocytes and fibroblasts containing oncogenic ras die after downregulation of PKC activity (11, 12, 13). The integration of Ras signaling has also been observed in Fas-induced apoptosis (12, 24). Furthermore, ras-transformed cells are susceptible to apoptosis upon suppression of NF-κB activation in a p53-independent fashion (35). These data provide evidence that, although oncogenic ras promotes unlimited cell proliferation under normal growth conditions, cells expressing activated ras retain the ability to undergo apoptosis. Other studies have indicated that abnormalities of tumor suppressors are important in the regulation of the susceptibility of tumor cells to apoptosis. It is not completely understood how changes in these tumor suppressors may regulate the threshold of the sensitivity of cells to apoptotic stimulations, and subsequently affect their fate. Since Ras activity has been directly linked to the inactivation of p53 and to the regulation of the susceptibility of cells to apoptosis (11, 17, 35, 46), it led us to investigate the role of p53 in Ras-mediated apoptosis. The expression of wild-type (wt) p53 in BALB or Swiss mouse fibroblasts did not change after transient expression of v-ras or acute increase of endogenous Ras activity by GAP antisense oligonucleotide. However, in stable ras transfectants, p53 was mutated. We also demonstrated that cells transiently transfected with ras or treated with GAP antisense oligonucleotides became susceptible to apoptosis, and this apoptotic process was dramatically augmented after PKC suppression, accompanied with Bax induction, in a p53-dependent fashion. In contrast, stable ras transfectants were less sensitive to PKC inhibition, and Bax was not induced. The results suggest that PKC is crucial for cells containing high Ras activity to survive and to be further transformed. Apoptosis mediated by transiently increased Ras activity is p53 dependent. After escaping from the Ras-elicited, p53-dependent apoptotic crisis, the stable ras transfectants still retain the ability to die, under circumstances in which endogenous PKC activity is eliminated, and this apoptosis is p53 independent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

Mouse fibroblasts, BALB (clone A31 initially developed from 14-day-old BALB/c mouse embryos) and Swiss, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.). The cells were infected with retroviral vector containing the v-Ki-ras or v-Ha-ras gene, respectively. After infection, the transfectants were subcloned and maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (containing 10% donor calf serum and Geneticin). The expression of the v-Ki- or v-Ha-ras gene was confirmed by Northern blot analysis.

For an acute increase of Ras activity or suppression of Bax expression, a 15 or 20 μM concentration of GAP or Bax antisense oligonucleotides was added into a cell culture for 48 h, and subsequently the cells were refed with medium containing a half dose of the oligonucleotides every 2 days. For transient transfection, cells were infected with ras or E6 and exposed to various treatments 48 h after the transfection.

GDP-GTP exchange assay.

BALB and Swiss cells without or with transiently or stably expressed ras were washed with phosphate-free RPMI medium containing 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum and cultured in the same medium with [32P]orthophosphate (0.5 mCi/ml) for 4 h. Subsequently, cells were lysed in lysis buffer (24). Equal amounts of cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Ras antibody (anti-Ras Ab) (Oncogene Science, Uniondale, N.Y.), and this was followed by the addition of goat anti-rat immunoglobulin-conjugated protein A-Sepharose beads. Precipitates were washed with lysis buffer, and bound nucleotides were eluted with the elution buffer containing 20 mM EDTA and a 25 μM concentration (each) of cold GDP and GTP at 65°C. The eluted products were separated on polyethyleneimine-cellulose plates (24). Quantitation was performed by densitometric scanning of autoradiograms using a laser densitometer.

Cell viability assays.

Cells (0.5 × 106 cells/ml) were cultured in the medium containing various concentrations of 1-O-hexadecyl-2-O-methyl-rac-glycerol (HMG; Calbiochem) for the times indicated in the figures or in the figure legends. Viable cells were determined and enumerated using trypan blue exclusion (11).

Flow cytometric determination of nuclear DNA fragmentation and terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay.

Cytofluorometric analysis was performed with a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.). The data analysis and display were performed using the Cell-Fit software program (Becton Dickinson). Cell-Fit provides data from the flow cytometer and real-time statistical analysis of the data, computed at 1-s intervals, and also discriminates doublets or adjacent particles. Briefly, following various treatments with HMG or other stimuli, cells (0.5 × 106/ml) were washed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline, fixed with 70% ethanol, and treated with RNase (10 ng/ml). Subsequently, cells were stained with propidium iodide (50 μg/ml). The stained samples were kept in the dark at 4°C overnight before flow cytometric analysis.

For the TUNEL assay, an in situ cell death detection kit (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, Ind.) was used. After the treatment, cells (0.5 × 106) were washed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline and incubated in 2% paraformaldehyde solution at room temperature. Following centrifugation, cells were resuspended in the permeabilization solution (0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.1% sodium citrate) for 2 min on ice and then stained with TUNEL reaction mixture. The samples were then analyzed with a FACScan and the Lysis II software program (Becton Dickinson).

RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis.

Following various treatments, total RNAs were isolated using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Inc.), quantified, separated by electrophoresis on formaldehyde-agarose gels, and transferred to nitrocellulose. 32P-labeled DNA probes were made by the random oligonucleotide primer method.

Protein analysis.

Cells were labeled with 100 μCi of [35S]methionine (New England Nuclear) for 4 h and lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (47). The protein concentrations of cell lysates were normalized. Equal amounts of total proteins from different cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with 1 μg of Abs recognizing wt p53, mutant (mu) p53, or the common region of p53 (generous gift from C. Prives, Columbia University). The immune complexes were recovered by using Sepharose CL-4B (Pharmacia) and were subsequently separated on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel.

RESULTS

Mouse fibroblasts with transient increase of Ras activity are more susceptible to apoptosis.

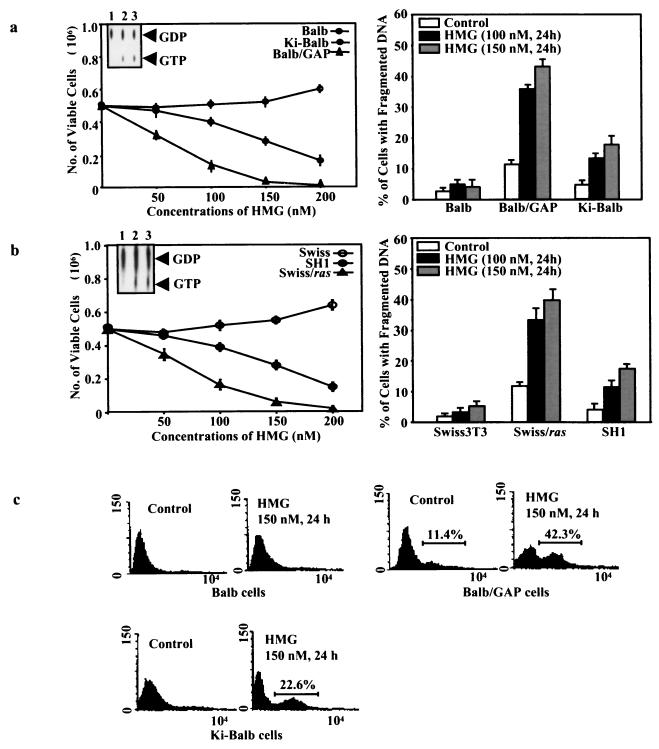

Murine BALB cells were transfected with v-Ki-ras (designated Ki-BALB cells), and Swiss fibroblasts were infected with v-Ha-ras (designated SH1 cells). Following subcloning, the expression of ras was examined by Northern blotting. The clones expressing moderate levels of ras transcripts were selected and employed in this investigation. To transiently increase Ras activity, BALB cells were treated with GAP antisense oligonucleotides (designated BALB/GAP cells) (9, 38, 45) or Swiss cells were transiently infected with v-Ha-ras (designated Swiss/ras cells). We previously demonstrated that v-ras-expressing cells undergo apoptosis after PKC downregulation (11-13). To test whether PKC inhibition has an effect on the cells transiently or stably overexpressing ras, a cell viability assay was first conducted. After exposing the cells to various doses of HMG (a PKC inhibitor) for 24 h, viable cells were counted using the trypan blue exclusion method (Fig. 1a and b, left panels). The numbers of BALB or Swiss cells with a transient increase of Ras activity started to decrease after the addition of 50 nM HMG, and only a few viable cells were left at 200 nM HMG. In contrast, the numbers of viable Ki-BALB and SH1 cells started to decline following addition of 150 nM HMG and became steeper at 200 nM HMG. The numbers of viable parental BALB or Swiss cells did not have obvious changes in response to various doses of HMG treatment. The slight increase of viable cells at 200 nM HMG may be due to the activation of other growth-related pathways elicited by strong suppression of PKC. The inserted panels are the results of the GDP-GTP exchange assay and indicate the active (GTP-bound) or inactive (GDP-bound) status of Ras in the cells. The GTP-bound form of Ras was undetectable in parental BALB or Swiss cells. The relative percentages of GTP-bound Ras versus the GDP-bound form in BALB/GAP, Ki-BALB, Swiss/ras, or SH1 cells was 19.4, 16.2, 21.6, or 17.8%, respectively, indicating an increased level of Ras activity in these cell lines.

FIG. 1.

Susceptibility of cells with differential increases of Ras activity to apoptosis. (a and b) For transient increase of Ras activity, BALB cells were cultured in the medium containing 20 μM GAP antisense oligonucleotide for 48 h or Swiss cells were transiently infected with v-Ha-ras for 2 days. Subsequently, parental BALB or Swiss cells, as well as the cells with transient (BALB/GAP and Swiss/ras cells) or stable (Ki-BALB and SH1 cells) increase of Ras activity, were cultured in media containing various concentrations of HMG for 24 h. Viable cells were enumerated afterward (left panels). Error bars represent the standard errors over five independent experiments. The inserted panels indicate the status of Ras in these cells. The cells were metabolically labeled with [32P]orthophosphate and lysed. Subsequently, Ras protein was immunoprecipitated and Ras-associated guanine nucleotides were separated on a thin-layer chromatogram. For DNA fragmentation assays (right panels), the cells were cultured in the medium containing 100 or 150 nM HMG for 24 h, and subsequently the percentages of the cells with fragmented DNA were examined by flow cytometry. Error bars represent the standard error over five independent experiments. (c) Flow cytometric profiles of DNA strand breaks in the cells labeled by TUNEL assay.

To confirm that the reduction of the viable cells after HMG treatment is due to apoptosis, a DNA fragmentation assay was conducted (Fig. 1a and b, right panels). The cells were treated with 100 or 150 nM HMG for 24 h and then stained with propidium iodide for flow cytometry analysis. The percentages of DNA fragmentation in the cells with transient increases in Ras activity after the treatment were dramatically increased to more than 30% (for treatment with 100 nM HMG) and 40% (for treatment with 150 nM HMG), respectively. In contrast, the percentages of Ki-BALB and SH1 cells with fragmented DNA were slightly augmented after addition of 100 nM HMG (about 12%) and became prominent after exposing the cells to 150 nM HMG (about 20%). Interestingly, the percentage of DNA fragmentation in the untreated cells with transient increases in Ras activity was higher than that in other cell lines (about 13%), which indicates the occurrence of an apoptotic crisis provoked by abnormally high Ras activity. The DNA fragmentation assay was also conducted in other stable ras transfectants, and similar results were obtained (data not shown).

To further demonstrate that the loss of viability in the cells with high Ras activity is the result of apoptosis, a TUNEL assay was performed (Fig. 1c). With or without HMG treatment, BALB, BALB/GAP, or Ki-BALB cells were permeabilized and labeled with tagged dUTP by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase to detect DNA strand breaks. The percentages of labeled BALB/GAP and Ki-BALB cells were 42.3 and 22.6%, respectively. In contrast, there was no significant increase in the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase labeling in BALB cells after treatment with 150 nM HMG. Again, under normal growth conditions, 11.4% of BALB/GAP cells contained broken DNA strands. Overall, the results from the TUNEL assay are comparable with those obtained from the DNA fragmentation analysis.

p53 is mutated in stable ras transfectants but not in cells with transiently increased Ras activity.

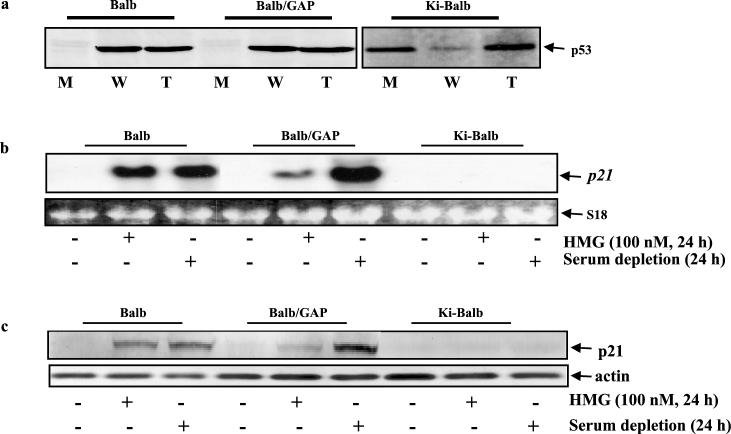

Tumor suppressor p53 possesses multiple functions, including regulation of apoptosis (50, 52). The deregulation of p53 mediated by various oncogenes frequently occurs in tumorigenesis (28). During the early stage of transformation, activated ras suppresses p53 through targeting MDM2 (42). Because cells transiently expressing ras were more susceptible to apoptosis after HMG treatment than the stable transfectants, the expression of p53 was examined in BALB, BALB/GAP, and Ki-BALB cells. After labeling the cells with [35S]methionine, whole-cell lysates were prepared, and subsequently p53 was immunoprecipitated with anti-wt, anti-mu, or anti-pan (recognizing both wt and mu proteins) p53 Ab (Fig. 2a). BALB and BALB/GAP cells expressed wt p53 only. Ki-BALB cells had a p53 protein that was recognized by the anti-pan p53 Ab, in which the expressed p53 mainly reacted with an anti-mu p53 Ab and only a detectable amount of the protein could be recognized by an anti-wt-p53 Ab. The reduction of wt p53 and the increase in mutated p53 were also observed in SH1 cells but not in Swiss/ras cells (data not shown). The same experiment was performed in several other stable ras clones, and similar results were obtained (data not shown). Thus, the data indicated that the accumulation of p53 mutations appears to be one event mediated by activated ras in the process of the establishment of the transformation.

FIG. 2.

Expression and function of p53 in cells with differential increases of Ras activity. (a) BALB, Ki-BALB, and BALB/GAP cells were [35S]methionine labeled, and the lysates were prepared. Subsequently, the lysates were immunoprecipitated with Abs directed against total p53 (lanes T), mu p53 (lanes M), or wt p53 (lanes W). The immune complexes were recovered and separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel. (b) Expression of p21 as shown by Northern blot analysis. With (+) or without (−) HMG treatment or serum starvation, the total RNAs from BALB, BALB/GAP, and Ki-BALB cells were prepared, and 15 μg of the RNAs from each sample was loaded on an agarose gel for Northern blotting. Subsequently, the blot was hybridized with 32P-labeled p21 probe. (c) Expression of p21 protein. The level of p21 in the cells was examined by Western blot analysis. The cell extracts were prepared from untreated or treated cells and then run on an SDS-12% polyacrylamide gel. The blot was probed with an anti-p21 Ab. After stripping, the same blot was also probed with an antiactin Ab.

To further determine the transcriptional function of p53 in the cells with differentially increased Ras activity, the expression and induction of cyclin inhibitor p21 (a p53-regulated gene) were examined (Fig. 2b). Northern blot analysis demonstrated that p21 was equally induced in BALB cells by HMG treatment or serum withdrawal from the medium, because both treatments mediate the cells to arrest in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (data not shown). p21 expression was moderately induced in BALB/GAP cells by HMG but was strongly elicited by serum depletion. In contrast, p21 could not be detected in Ki-BALB cells after either HMG treatment or serum depletion, consistent with loss of p53 function in these cells. p21 was not expressed under normal growth conditions in all three cell lines. To further confirm the deregulation of p53 in Ki-BALB cells, the expression of p21 protein was examined by Western blotting (Fig. 2c). Similar results were obtained, in which p21 was induced in BALB cells by two different treatments. In contrast, p21 protein expression was slightly elicited in BALB/GAP cells by HMG but strongly augmented by serum starvation. Again, there was no p21 induction in Ki-BALB cells after these two treatments. The same experiments were also conducted with other clones of ras transfectants, and similar results were obtained (data not shown). Equal loading of total RNAs or proteins was monitored by the expression of S18 from rRNA stained with ethidium bromide or by the expression of actin protein detected by antiactin Ab, respectively.

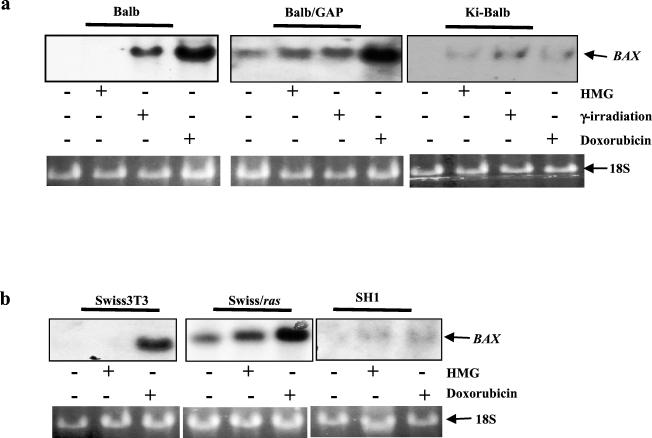

Bax is induced in cells with transient increase of Ras activity.

Bax, a p53-regulated gene, is involved in p53-dependent apoptosis in certain cell types (36, 37). To test whether Bax is induced in cells with increased Ras activity, before the onset of Ras-mediated apoptosis, Northern blot analysis was conducted (Fig. 3a, upper panel). The different doses of HMG (100 nM for the cells with a transient increase of Ras activity or 150 nM for the ras transfectants) were chosen based on the different sensitivities of these cells to the inhibitor for the induction of apoptosis (Fig. 1). Other apoptotic stimuli (doxorubicin and γ-irradiation) were used as positive controls. Bax was induced in BALB/GAP cells following treatment with doxorubicin (0.5 μg/ml, 15 h), γ-irradiation (400 rads), or HMG (100 nM, 15 h). The stronger induction of Bax by doxorubicin than other reagents (about 1.5-fold) may reflect the different usage of the promoter(s) and/or enhancer(s). Bax was moderately expressed in untreated BALB/GAP cells. This is consistent with the data shown in Fig. 1, in which a moderate magnitude of apoptosis was elicited in these cells. In contrast, Bax was slightly expressed in Ki-BALB cells after HMG, γ-irradiation, or doxorubicin treatment. However, in parental BALB cells, Bax was not induced by HMG, because PKC inhibition was not apoptotic in BALB cells. Perhaps, under such conditions, a functional transcription complex for the induction of Bax is unable to assemble in BALB cells. Equal loading of total RNA was monitored by the expression of 18S on the Northern blot (Fig. 3a, lower panel).

FIG. 3.

Effects of acute or chronic increase of Ras activity on Bax induction and function. (a and b) Cells were treated with HMG for 15 h (100 nM for BALB/GAP and Swiss/ras cells; 150 nM for BALB, Ki-BALB, Swiss, and SH1 cells). The cells were also exposed to 400 rads of γ-irradiation and 0.5 μg of doxorubicin/ml for 15 h. Subsequently, 15 μg of total mRNA from each sample was prepared. The Northern blots were hybridized with 35P-labeled Bax probe.

To confirm that Bax was differentially induced by HMG in cells with transiently or stably increased Ras activity, Northern blotting for Bax expression was also conducted in Swiss cells transiently or stably expressing v-Ha-ras. Again, Bax was induced by HMG in Swiss/ras cells but not in SH1 or parental Swiss cells (Fig. 3c, upper panels). However, doxorubicin strongly elicited gene expression in Swiss and Swiss/ras cells but not in SH1 cells. The equal loading of the samples was monitored by 18S expression on the Northern blot (Fig. 3c, lower panel). Overall, the data indicate a correlation between the requirement of a functional p53 and the induction of Bax in the apoptotic process mediated by the transient increase of Ras activity.

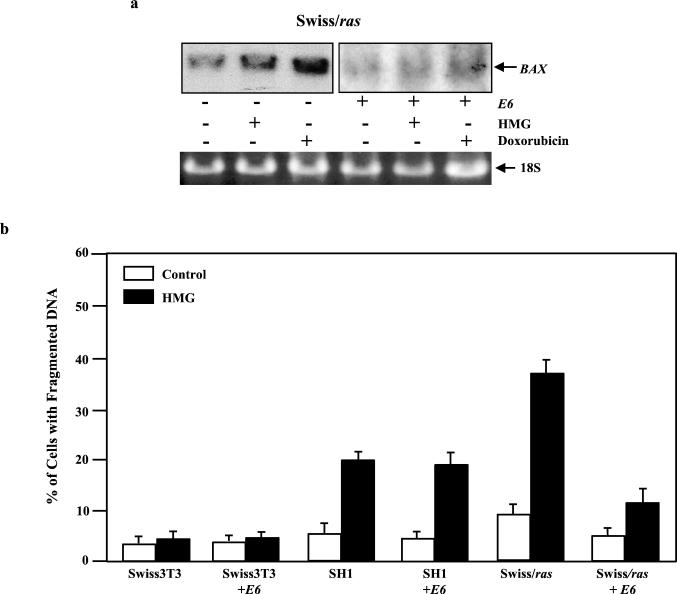

E6 or Bax antisense oligonucleotides suppress apoptosis mediated by transient increases in Ras activity.

To further determine the p53 dependency of Bax expression and the induction of apoptosis mediated by transient increases in Ras activity, a retroviral vector containing the papillomavirus E6 gene (which targets and causes the rapid degradation of p53) was employed. Following the coinfection of Swiss cells with v-ras and E6, the induction of Bax mediated by two different treatments was examined by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 4a, upper panel). A low level of Bax was detected in Swiss/ras cells under normal growth conditions, and the expression was further induced by HMG (1.8-fold) and doxorubicin (about 4-fold). However, the introduction of E6 blocked Bax expression in untreated Swiss/ras cells and also inhibited the induction of the gene mediated by HMG or doxorubicin in these cells. The same results were obtained from BALB/GAP cells (data not shown). The equal loading of the samples was also monitored by 18S expression on the Northern blot (Fig. 4a, lower panel).

FIG. 4.

Effect of E6 on apoptosis in cells with differential increases of Ras activity. (a) E6 and v-ras constructs were transiently coinfected into Swiss 3T3 cells. The cells with (+) or without (−) expression of E6 were incubated with 100 nM HMG for 15 h. Subsequently, 15 μg of total mRNA from each sample was prepared. The Northern blot was hybridized with 35P-labeled Bax probe. (b) Cells with differential increases of Ras activity, with or without expression of E6, were treated with HMG for 24 h. Subsequently, the DNA fragmentation assay was performed. Control, no treatment; HMG, 100 nM HMG for Swiss/ras cells with or without expression of E6 or 150 nM HMG for Swiss 3T3 and SH1 cells with or without expression of E6. Error bars represent the standard error over five independent experiments.

To determine further the effect of E6 on the induction of Ras-mediated apoptosis, a DNA fragmentation assay was conducted in the cells with or without expression of E6 (Fig. 4b). The percentages of DNA fragmentation in Swiss/ras cells in response to HMG (100 nM) treatment was dramatically increased (to about 40%), and the magnitude of Ras-mediated apoptosis was significantly reduced by introducing E6 into the cells (to less than 15%). E6 also inhibited DNA fragmentation in untreated Swiss/ras cells. The results indicate that the apoptotic process mediated by transiently expressed v-ras is in part regulated by p53. However, the incomplete suppression of Ras-induced cell death suggests that other p53-independent signaling pathways may participate in the process. Again, only about 20% of the stable ras transfectant (SH1 cells) had fragmented DNA after the addition of HMG (150 nM), and the introduction of E6 had no inhibitory effect on the cells.

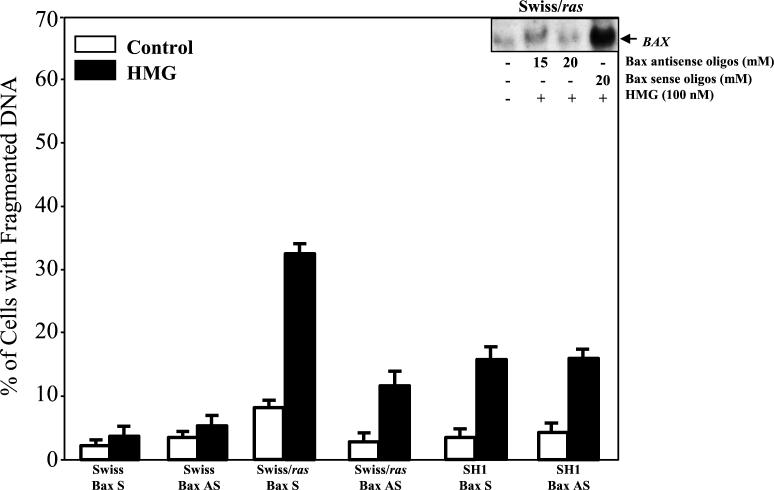

We next tested whether Bax antisense oligonucleotides also have a negative effect on the apoptotic process. The concentration of the antisense oligonucleotide required to suppress Bax expression was determined by a dose titration experiment (Fig. 5, inserted panel). Swiss/ras cells were exposed to a 15 or 20 μM concentration of Bax antisense oligonucleotide or 20 μM Bax sense oligonucleotide for 48 h, and Northern blotting of Bax expression was then conducted with or without HMG treatment. A 15 μM concentration of the antisense oligonucleotide moderately inhibited Bax induction, and a 20 μM concentration of the antisense oligonucleotide significantly suppressed Bax expression. The addition of the sense oligonucleotide did not affect the induction of the gene. Subsequently, Swiss, Swiss/ras, or SH1 cells were cultured in the medium containing a 20 μM concentration of either the Bax sense or antisense oligonucleotide for 48 h, and then the DNA fragmentation assay was performed, under normal growth conditions or after PKC suppression (Fig. 5). The Bax antisense oligonucleotide partially inhibited the generation of DNA fragmentation mediated by HMG (100 nM) in Swiss/ras. It is notable that the inhibitory effect of the antisense oligonucleotide is similar to that of E6. The addition of the sense oligonucleotide did not affect Ras-mediated apoptosis in the same cells. A moderate number of SH1 cells had fragmented DNA after the addition of 150 nM HMG, and Bax antisense oligonucleotide had no effect on the formation of DNA fragmentation. Apoptosis did not occur in parental Swiss cells in the presence of either the sense or antisense oligonucleotide. The data again provide evidence that Bax is involved only in the regulation of apoptosis mediated by transient expression of Ras.

FIG. 5.

Effect of Bax antisense oligonucleotide on apoptotic process. In the inserted panel, the cell lysates from Swiss/ras cells were prepared after the cells were cultured in 15 or 20 μM Bax antisense oligonucleotide or 20 μM Bax sense oligonucleotide for 48 h. Subsequently, 15 μg of the total RNAs from each sample was prepared. The Northern blot was hybridized with 35P-labeled Bax probe. For the DNA fragmentation assay, Swiss 3T3, Swiss/ras, or SH1 cells were cultured in the medium containing a 20 μM concentration of either Bax sense or antisense oligonucleotide for 48 h. The cells were then treated with HMG for 24 h (150 nM HMG for Swiss 3T3 and SH1 cells; 100 nM HMG for Swiss/ras cells), and the percentages of the cells containing fragmented DNA were analyzed. Error bars represent the standard error over five independent experiments.

The introduction of wt p53 changes the susceptibility of stable ras transfectants to apoptosis.

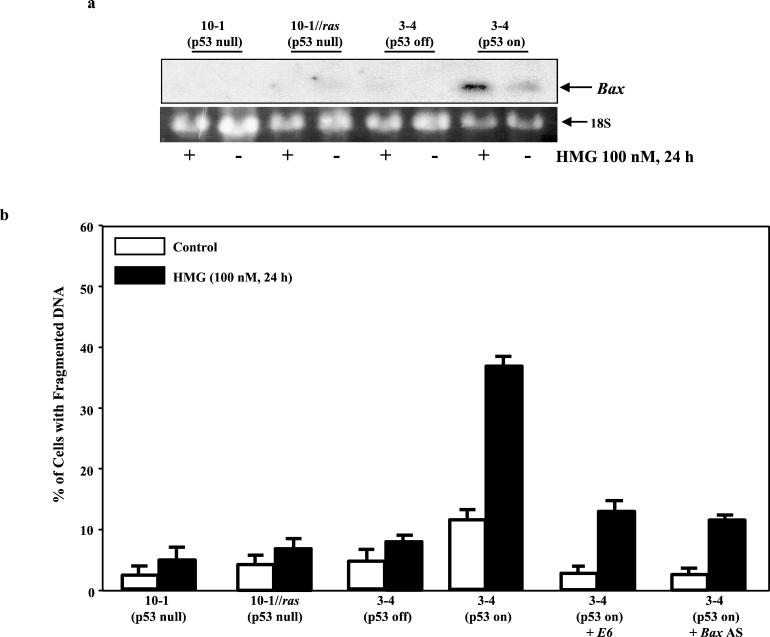

Because p53 is a key player in the regulation of Ras-induced apoptosis, we examined whether the introduction of wt p53 affects the susceptibility of stable ras transfectants to apoptosis. Mouse p53-null fibroblasts (10-1) and 3-4 cells that were generated by stable cotransfection of 10-1 cells with v-Ha-ras and the temperature-sensitive murine p53val135 were used (14). p53-null 10-1 cells were also transiently infected with v-Ha-ras (designated 10-1/ras cells). The Northern blotting for Bax induction was conducted with these cells. Bax was not induced by HMG (100 nM) in either 10-1 cells or 10-1/ras cells (Fig. 6a, upper panel). In 3-4 cells, p53 is in mutant form at 37°C, while at 32°C, it changes to the wt conformation. Bax was not induced by HMG when 3-4 cells grew at 37°C. However, after culturing the cells at 32°C, Bax was slightly induced, and the expression was dramatically augmented by HMG. The susceptibility of these cells to Ras-mediated apoptosis was subsequently tested (Fig. 6b). HMG (100 nM) did not elicit apoptosis in 10-1 cells with or without transiently expressed v-Ha-ras. In 3-4 cells, once p53 changed to the wt conformation, a moderate number of the cells spontaneously underwent apoptosis, and the magnitude of cell death was dramatically augmented after adding HMG. We then tested the percentage of DNA fragmentation after infecting 3-4 cells with E6 or growing the cells in the medium containing Bax antisense oligonucleotides. Both E6 and Bax antisense oligonucleotides inhibited apoptosis that spontaneously occurred or were further enhanced by HMG in 3-4 cells, when p53 in the cells was in its wt conformation. The data suggest that, in order to survive, activated ras, together with other prosurvival factors, may target wt p53 and further suppress the apoptotic crisis-related signaling.

FIG. 6.

Effect of inducible p53 on apoptosis. (a) 10-1 (p53-null), 10-1/ras (10-1 cells transiently expressing Ha-ras), and 3-4 (containing temperature-inducible p53) cells were treated with HMG for 15 h. For p53 induction, 3-4 cells were cultured at 32°C in the medium containing HMG for 15 h. Subsequently, 15 μg of total mRNA from each sample was prepared. The Northern blots were hybridized with 35P-labeled Bax probe. (b) The cells were treated with HMG for 24 h under the conditions described for panel a. Subsequently, the DNA fragmentation assay was performed. Error bars represent the standard error over five independent experiments.

Induction of Ras-mediated apoptosis in tumor cells harboring wt p53.

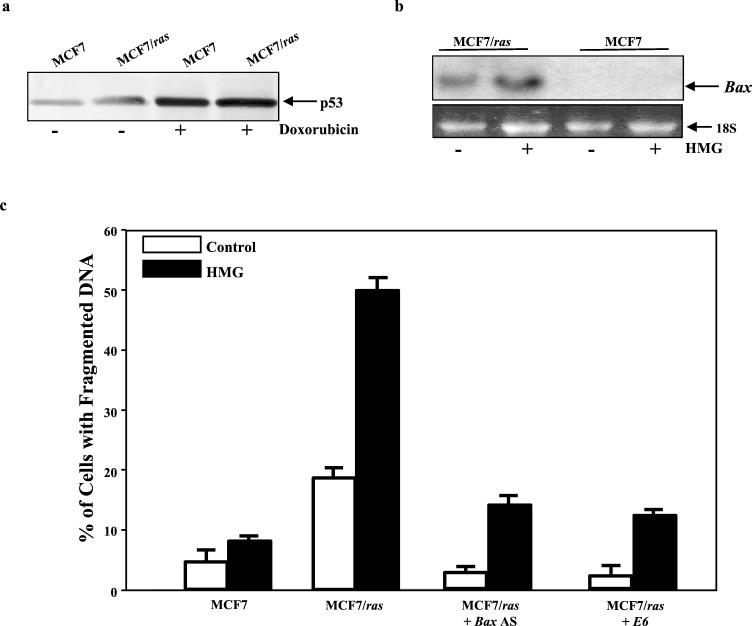

We then tested whether transient increase of Ras activity renders tumor cells expressing wt p53 susceptible to apoptosis. A human breast adenocarcinoma cell line (MCF7) has been shown to harbor wt p53 and possess nonmutated endogenous Ras (2, 10). The induction of p53 in MCF7 cells was first examined. Under normal growth conditions, MCF7 cells express a low amount of wt p53 protein, and the level of the protein expression was slightly increased (about 0.8-fold) after transiently introducing v-Ha-ras into MCF7 cells (designated MCF7/ras cells) (Fig. 7a). However, the expression was dramatically augmented (three- to fourfold) 15 h after addition of doxorubicin (0.5 μg/ml), indicating that p53 in MCF7 cells is functional. The induction of Bax was also examined by Northern blotting (Fig. 7b). Bax was not expressed in MCF7 cells, with or without HMG treatment (100 nM for 15 h). The gene was able to be induced after transient introduction of v-Ha-ras into MCF7 cells and strongly elicited by HMG in these cells. Subsequently, the susceptibilities of MCF7 and MCF7/ras cells to Ras-induced apoptosis were tested by DNA fragmentation assay (Fig. 7c). With or without HMG treatment, a very low percentage of MCF7 cells had fragmented DNA. After introducing v-Ha-ras into MCF7 cells, a moderate percentage of the cells underwent apoptosis, and the magnitude of cell death was dramatically augmented after addition of HMG. The induction of apoptosis was also examined in MCF7/ras cells either treated with Bax antisense oligonucleotide or infected with E6. Both treatments suppressed Ras-induced apoptosis elicited by HMG. The data again indicate that apoptosis induced by transiently expressed v-ras is p53 dependent.

FIG. 7.

Increasing susceptibility to apoptosis in MCF7 cells transiently expressing v-ras. (a) MCF7 cells and MCF7/ras cells (MCF7 cells transiently expressing v-Ha-ras) were treated with doxorubicin (0.5 μg/ml) for 15 h. The whole-cell lysates from treated or untreated cells were prepared. The immunoblotting for p53 expression was performed. (b) The cells were treated with HMG for 24 h (150 nM for MCF7; 100 nM for MCF7/ras cells). Subsequently, 15 μg of total mRNA from each sample was prepared. The Northern blots were hybridized with 32P-labeled Bax probe. (c) The MCF7 and MCF7/ras cells were treated with HMG for 24 h. Subsequently, the DNA fragmentation assay was performed. The same experiment was also conducted in MCF7/ras cells treated with Bax antisense oligonucleotide or transiently expressing E6, prior to HMG treatment. Error bars represent the standard error over five independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Activated ras transforms a variety of primary cell lines, with or without cooperative oncogenes (50). Ras functions through various parallel or downstream signals (including PKC-dependent or -independent pathways), leading to cell growth and differentiation (18). It has been reported that, under certain circumstances (such as Fas ligation or PKC downregulation), Ras also promotes apoptosis (11, 17, 35, 46). However, the mechanism of Ras-mediated apoptosis has not been well defined. In this study, we demonstrated that transiently expressing or upregulating Ras activity in mouse fibroblasts elicits an apoptotic crisis. However, these same cells that express wt p53 are more susceptible to apoptosis in response to PKC suppression than the stable ras transfectants in which p53 is often mutated. Apoptosis mediated by transient increase of Ras activity is p53 dependent, and Bax is involved in this process. In contrast, we find no evidence of a role for p53 in the regulation of apoptosis in cells that stably express v-ras.

During the early stage of transformation, cells undergo a period of crisis in which the majority of cells die before permanent establishment of malignancy (21, 43, 49, 51, 53). This phenomenon has also been noticed in the establishment of immortal cell lines. For instance, myc overexpression rapidly activates p53 and triggers an apoptotic crisis in primary mouse embryo fibroblasts (53). Some mouse embryo fibroblasts survive the crisis by inactivating wt p53 or other cell cycle checkpoint regulators during the process and become immortal. Our study, which compares the effects of transient and stable v-ras expressions, provides a new model for further understanding potential interactions among activated Ras, p53, and PKC. Studies have shown that PKC is involved in a variety of diverse signaling pathways, including its interaction with Ras. Moreover, PKC activity is important for tumor promotion (6, 29, 38). Our study demonstrates that a transient but persistent increase of Ras activity in cells transmits a signal to downstream effectors; however, the decision to grow or to undergo apoptosis depends upon p53 and PKC. In general, p53, as a guardian of the genome, eliminates those cells containing abnormally high Ras activity (pretransformed) via apoptosis during the early stages of transformation. PKC, as a survival-promoting factor, suppresses the activities of various proapoptotic factors, thereby helping cells to escape from p53 surveillance. The elimination of PKC activity releases the apoptotic factors from this suppression and dramatically enhances Ras-mediated apoptosis. Alternatively, under such conditions, suppression of endogenous PKC activity further provokes the collision among internal, unstable signals mediated by increases of Ras activity and in turn activates massive cell death signaling pathways. In the stable ras transfectants, PKC appears to be required for adapting gene mutations and genetic changes mediated by oncogenic ras. At the same time, this kinase may, together with oncogenic ras, block programmed cell death, especially p53-mediated apoptotic signaling. However, transformed cells are not absolutely immortal and, under certain circumstances, have the propensity to commit suicide. Our study demonstrates that the stable ras transfectants undergo programmed cell death once PKC activity is inhibited, in a p53-independent fashion. It is possible that the blockade of PKC activity causes clashes of hyperproliferative signals in the cells with unstable genome mediated by loss of wt p53 and in turn lifts the ban for p53-independent apoptosis.

Mutation of the p53 gene is a common event in tumorigenesis and often occurs in the late stage of malignancy (5, 8, 30, 48). In various types of cells transformed by oncogenic ras, p53 appears to be mutated. For example, the introduction of Ha-ras into mouse prostate cells mediates the mutation of endogenous p53 and induces hyperplasia in the reconstituted mouse prostate organ (33). In colon cancer cells, ras mutation precedes p53 mutations (30, 44, 45). Recently, it has been reported that, in the early stage of transformation, Ras activity negatively regulates p53 through modulating MDM2 (42). The BALB and Swiss cell lines employed in this study possess wt p53. Therefore, it is possible that, during this process, the autoregulatory loop for maintaining normal function of p53 is disrupted by persistent increase of Ras activity, which facilitates error-prone mutations, including p53 mutation. The loss of wt p53 expression or function mediated by oncogenic ras in cells also cripples apoptotic crisis-related signals and leads to the increased tolerance to abnormally high Ras activity. However, MCF7 breast cancer cells are tumor cells that express wt p53 and contain nonmutated Ras. In the process of tumorigenesis, the loss of the expression or function of other tumor suppressors, for example BRCA1 and -2, may play an important role in the regulation of the susceptibility of the cells to apoptotic crisis.

Bax, a transcriptional target of p53, has been suggested to be involved in certain types of apoptotic processes (9, 20). Bax is induced by a transient increase of Ras activity. The introduction of E6 into the cells with a transient increase of Ras activity to degrade p53 inhibits the Bax induction, and, at the same time, dramatically reduces Ras-mediated apoptosis. The apoptotic process was also greatly diminished by treating the same cells with Bax antisense oligonucleotide, with a magnitude similar to that achieved by E6, which presents a linear relationship between p53 and Bax in the regulation of Ras-mediated apoptosis. Therefore, we conclude that a transient increase of Ras activity activates p53-mediated apoptotic machinery in which Bax activity is required. In addition, the study shows that HMG does not induce Bax expression in parental BALB or Swiss cells that contain wt p53, and only mediates G1 arrest in these cells (data not shown). p53 is able to sense or distinguish growth arrest and apoptotic signals (22, 34, 50, 54). Because PKC suppression is not apoptotic to these cells, it is reasonable to believe that the p53-dependent transcriptional factors which regulate the apoptotic process do not converge under this condition in the cells. It is also conceivable that other cis elements exist within the promoter-enhancer region of Bax which discriminates such differences. Overall, wt p53 and Bax appear to be the key players in the induction of Ras-mediated apoptosis initiated by transient increase of Ras activity. The incomplete blockades of the apoptotic process by either E6 or Bax antisense oligonucleotide indicate that multiple pathways are involved in Ras-induced apoptosis.

The present study also demonstrates that the pattern of the induction of p21 in the cells containing a transient increase of Ras activity (BALB/GAP), in response to PKC suppression, is very different from Bax expression. Under normal growth conditions, p21 could not be detected in these cells, and the addition of HMG only moderately induced the gene, in comparison with that mediated by serum starvation in the same cells or by the same drug in BALB cells. In BALB/GAP cells, the apoptotic signaling elicited by HMG may increase the recruitment of p53 and further allow for the specific binding of p53 to a death-related element(s) (such as Bax), whereas less p53 may transactivate p21 expression. This model was suggested by the experiments with irradiated cells, in which Bax is maximally induced and GADD45 is only slightly expressed, despite the apparently lower affinity of wt p53 for the Bax site (22, 52). Under apoptotic conditions, the activation of apoptosis-related promoters, such as the Bax promoter, by p53 may be favored. However, the mechanism of the preferential activation of p53 is still unclear.

There are considerable data indicating that inappropriately increasing Ras activity interferes with the normal function(s) of cell cycle checkpoints (4, 16, 18, 19, 23, 31). Selective induction of activated Ha-ras stimulates serum-depleted cells to progress from G1 arrest into S phase. Other studies demonstrated that oncogenic ras shortens the G1 phase of the cell cycle. It is possible that, in order to tolerate the environment or to survive, activated ras, together with prosurvival factors such as PKC and NF-κB, cripples cell cycle surveillance by targeting tumor suppressors and promotes cell proliferation. The results generated from 3-4 cells indicate that p53 is a target for oncogenic ras to regulate the apoptotic process. After restoration of the wt conformation of p53, the cells regain the susceptibility to Ras-induced cell death in a p53/Bax-dependent fashion. The fact that MCF7 cells become susceptible to Ras-mediated cell death once Ras activity is transiently increased provides further evidence for the connection between Ras and wt p53 in the regulation of apoptosis. In the future, the identification of the factors which are involved in the regulation of the p53-independent, apoptotic process in stable ras transfectants will help us to further understand the mechanism(s) of Ras-mediated apoptosis and may offer a potential cancer therapy for targeting elements at different stages of oncogenic ras-mediated malignancy.

In the process of signal transduction, PKC transmits the proper message for cell activation or cell cycle progression. Suppression of PKC by various methods causes normal cells to arrest in the G1 phase of the cell cycle; however, it augments or elicits the apoptotic process in cells containing high Ras activity. This indicates that PKC is a crucial factor for the survival and further transformation of cells with abnormally high Ras activity. The present investigation also suggests that the cells at various stages of ras-mediated transformation possess different susceptibilities to apoptosis. The discrepancy of the susceptibilities to apoptosis is regulated, in part, by Ras, PKC, and p53.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. V. Faller and C. Vaziri for the critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank C. Vaziri for providing various constructs and reagents.

This work was supported by a grant from the American Cancer Society (RPG-00-111-01-MGO awarded to C.-Y.C.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, J. M., and S. Cory. 1991. Transgenic models of tumor development. Science 254:1161-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ameyar, M., V. Shatrov, C. Bouquet, C. Capoulade, Z. Cai, R. Stancou, C. Badie, H. Haddada, and S. Chouaib. 1999. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of wild-type p53 gene sensitizes TNF resistant MCF7 derivatives to the cytotoxic effect of this cytokine: relationship with c-myc and Rb. Oncogene 18:5464-5472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amundson, S. A., T. G. Myers, and A. J. Fornace, Jr. 1998. Roles for p53 in growth arrest and apoptosis: putting on the brakes after genotoxic stress. Oncogene 17:3287-3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arber, N., T. Sutter, M. Miyake, S. M. Kahn, V. S. Venkatraj, A. Sobrino, D. Warburton, P. R. Holt, and I. B. Weinstein. 1996. Increased expression of cyclin D1 and the Rb tumor suppressor gene in c-K-ras transformed rat enterocytes. Oncogene 12:1903-1908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azzoli, C. G., M. Sagar, A. Wu, D. Lowry, H. Hennings, D. L. Morgan, and W. C. Weinberg. 1998. Cooperation of p53 loss of function and v-Ha-ras in transformation of mouse keratinocyte cell lines. Mol. Carcinogenesis 21:50-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baier-Bitterlich, G., F. Ulberall, B. Bauer, F. Fresser, G. Wachter, H. Grunicke, G. Utermann, A. Altman, and G. Baier. 1996. Protein kinase C-theta isoenzyme selective stimulation of the transcription factor complex AP-1 in T lymphocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1842-1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bos, J. L. 1989. ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 49:4682-4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boukamp, P., W. Peter, U. Pascheberg, S. Altmeier, C. Fasching, E. J. Stanbridge, and N. E. Fusenig. 1995. Step-wise progression in human skin carcinogenesis in vitro involves mutational inactivation of p53, ras oncogene activation and additional chromosome loss. Oncogene 11:961-969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caelles, C., A. Heimberg, and M. Karin. 1994. p53-dependent apoptosis in the absence of transcriptional activation of p53-target genes. Nature 370:220-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai, Z., C. Capoulade, C. Moyret-Lalle, M. Amor-Gueret, J. Feunteun, A. K. Larsen, B. B. Paillerets, and S. Chouaib. 1997. Resistance of MCF7 human breast carcinoma cells to TNF-induced cell death is associated with loss of p53 function. Oncogene 15:2817-2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, C.-Y., and D. V. Faller. 1995. Direction of p21Ras-generated signals cell growth or apoptosis is determined by protein kinase C and Bcl-2. Oncogene 11:1487-1498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, C.-Y., J. Liou, L. W. Forman, and D. V. Faller. 1998. Differential regulation of discrete apoptotic pathways by Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 273:16700-16709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, C-Y., J. Liou, L. W. Forman, and D. V. Faller. 1998. Correlation of genetic instability and apoptosis in the presence of oncogenic Ki-Ras. Cell Death Diff. 5:984-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, X., J. Bargonetti, and C. Prives. 1995. p53, through p21(WAF1/CIP1), induces cyclin D1 synthesis. Cancer Res. 55:4257-4263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark, G. J., J. K. Westwick, and C. J. Der. 1997. p120GAP modulates Ras activation of Jun kinase and transformation. J. Biol. Chem. 272:1677-1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Downward, J. 1997. Cell cycle: routine role for Ras. Curr. Biol. 7:258-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Downward, J. 1998. Ras signalling and apoptosis. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 8:49-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downward, J., J. D. Graves, P. H. Warne, S. Rayter, and D. A. Cantrell. 1990. Stimulation of p21ras upon T-cell activation. Nature 346:719-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Filmus, J., A. I. Robles, W. Shi, M. J. Wong, L. L. Colombo, and C. J. Conti. 1994. Induction of cyclin D1 overexpression by activated ras. Oncogene 9:3627-3633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher, D. E. 1994. Apoptosis in cancer therapy: crossing the threshold. Cell 78:539-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franza, B. R., K. Maruyama, J. I. Garrels, and H. E. Ruley. 1986. In vitro establishment is not a sufficient prerequisite for transformation by activated Ras oncogenes. Cell 44:409-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedlander, P., Y. Haupt, C. Prives, and M. Oren. 1996. A mutant p53 that discriminates between p53-responsive gene cannot induce apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:4961-4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gille, H., and J. Downward. 1999. Multiple Ras effector pathways contribute to G1 cell cycle progression. J. Biol. Chem. 274:22033-22042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gulbins, E., R. Bissonnette, A. Mahoubi, S. Martin, W. Nishioka, T. Brunner, G. Baier, G. Baier-Bitterlich, C. Byrd, F. Lang, R. Kolesnick, and D. Green. 1995. Fas-induced apoptosis is mediated via a ceramide-initiated Ras signaling pathway. Immunity 2:341-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson, L., K. Mercer, D. Greenbaum, R. T. Bronson, D. Crowley, D. A. Tuveson, and T. Jacks. 2001. Somatic activation of the K-ras oncogene causes early onset lung cancer in mice. Nature 410:1111-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joneson, T., M. A. White, M. H. Wigler, and D. Bar-Sagi. 1996. Stimulation of membrane ruffling and MAP kinase activation by distinct effectors of Ras. Science 271:810-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khosravi-Far, R., and C. J. Der. 1994. The Ras signal transduction pathway. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 13:67-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ko, L. J., and C. Prives. 1996. p53: puzzle and paradigm. Genes Dev. 10:1054-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, J. Y., Y. A. Hannun, and L. M. Obeid. 1996. Ceramide inactivates cellular protein kinase C alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 271:13169-13174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lengauer, C., W. Kenneth, and B. Vogelstein. 1997. DNA methylation and genetic instability in colorectal cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:2545-2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, J., J. Chao, M. Jiang, S. Ng, J. J. Yen, and H. Yang-Yen. 1995. Ras transformation results in an elevated level of cyclin D1 and acceleration of G1 progression in NIH 3T3 cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:3654-3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowy, D. R. 1993. Function and regulation of Ras. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62:851-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu, X., S. H. Park, T. C. Thompson, and D. P. Lane. 1992. ras-induced hyperplasia occurs with mutation of p53, but activated ras and myc together can induce carcinoma without p53 mutation. Cell 70:153-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludwig, R. L., S. Bates, and K. H. Vousden. 1996. Differential activation of target cellular promoters by p53 mutants with impaired apoptotic function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:4952-4960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayo, M. W., C.-Y. Wang, P. C. Cogswell, K. S. Rogers-Graham, S. W. Lowe, C. J. Der, and A. S. Baldwin. 1997. Requirement of NFκB activation to suppress p53-independent apoptosis induced by oncogenic Ras. Science 278:1812-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyashita, T., S. Krajewski, M. Krajewska, H. G. Wang, H. K. Lin, D. A. Liebermann, B. Hoffman, and J. C. Reed. 1994. Tumor suppressor p53 is a regulator of bcl-2 and Bax gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene 9:1799-1805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyashita, T., and J. C. Reed. 1995. Tumor suppressor p53 is a direct transcriptional activator of the human Bax gene. Cell 80:293-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monks, C. R. F., H. Kupfer, I. Tamir, A. Barlow, and A. Kupfer. 1997. Selective modulation of protein kinase C-theta during T-cell activation. Nature 385:83-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oltvai, Z., C. Milliman, and S. J. Korsmeyer. 1993. Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that accelerates programmed cell death. Cell 74:609-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quin, R.-G., F. McCormick, and M. Symons. 1996. An essential role for Rac in Ras transformation. Nature 374:457-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reed, J. C. 1994. Bcl-2 and the regulation of programmed cell death. J. Cell Biol. 124:1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ries, S., C. Biederer, D. Woods, O. Shifman, S. Shirasawa, T. Sasazuki, M. McMahon, M. Oren, and F. McCormick. 2000. Opposing effects of Ras and p53: transcriptional activation of mdm2 and induction of p19ARF. Cell 103:321-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenberg, N., and D. Baltimore. 1976. A quantitative assay for transformation of bone marrow cells by Abelson murine leukemia. J. Exp. Med. 143:1453-1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shaw, P., R. Bovey, S. Tardy, R. Sahli, B. Sordat, and J. Costa. 1992. Induction of apoptosis by wild-type p53 in a human colon tumor-derived cell line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:4495-4499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shirasawa, S., M. Furuse, N. Yokoyama, and T. Sasazuki. 1993. Altered growth of human colon cancer lines disrupted at activated Ki-ras. Science 260:85-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanaka, N., M. Ishihara, M. Kitagawa, H. Harada, T. Kimura, T. Matsuyama, M. S. Lamphier, S. Aizawa, T. W. Mak, and T. Taniguchi. 1994. Cellular commitment to oncogene-induced transformation or apoptosis is dependent on the transcription factor IRF-1. Cell 77:829-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thome, K. C., A. Radfar, and N. Rosenberg. 1997. Mutation of Tp53 contributes to the malignant phenotype of Abelson virus-transformed lymphoid cells. J. Virol. 71:8149-8156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tuveson, D. A., and T. Jacks. 1999. Modeling human lung cancer in mice: similarities and shortcomings. Oncogene 18:5318-5324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Unnikrishnan, I., A. Radfar, J. Jenab-Wolocott, and N. Rosenberg. 1999. p53 mediates apoptotic crisis in primary Abelson virus-transformed pre-B cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:4825-4831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vogelstein, B., and K. W. Kinzler. 1992. p53 function and dysfunction. Cell 70:523-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vousden, K. H. 2000. p53: death star. Cell 103:691-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vousden, K. H., and G. F. Vande Woude. 2000. The ins and outs of p53. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:E178-E180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weinber, R. A. 1989. Oncogenes, antioncogenes, and the molecular bases of multistep carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 49:3713-3736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whitlock, C. A., S. F. Ziegler, and O. N. Witte. 1983. Progression of the transformed phenotype in clonal lines of Abelson virus-infected lymphocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3:596-604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]