Abstract

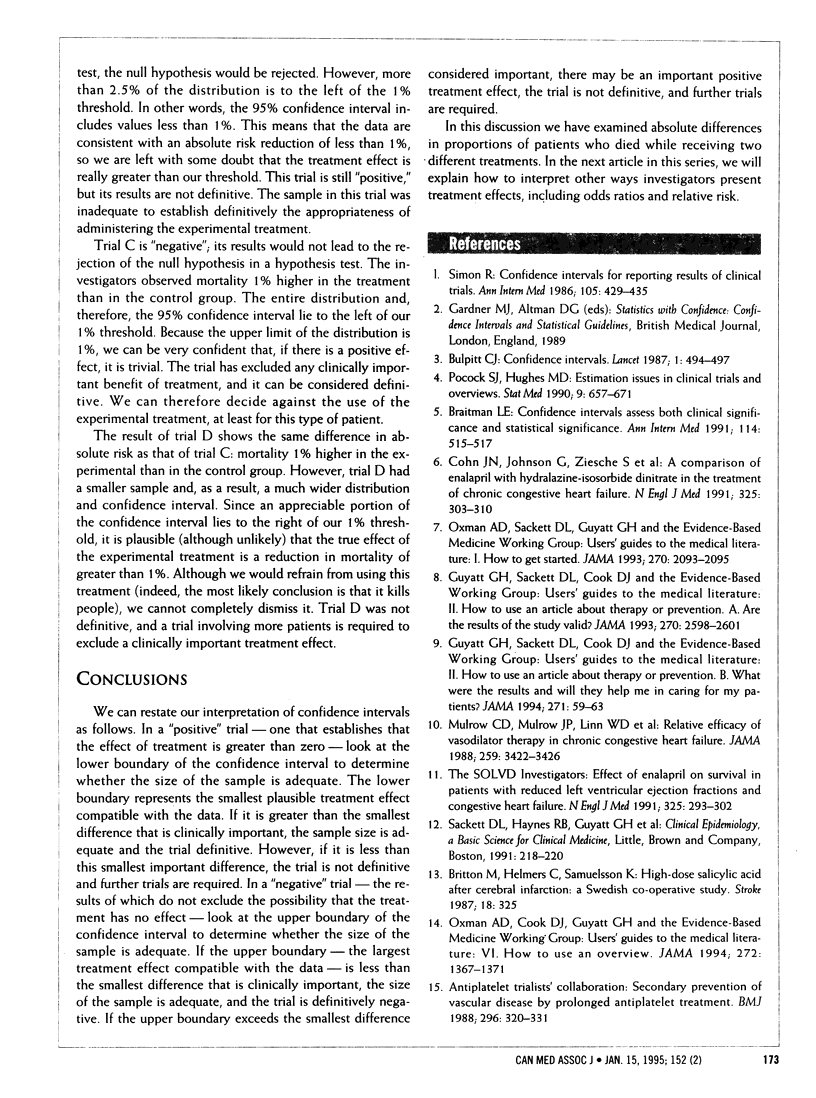

In the second of four articles, the authors discuss the "estimation" approach to interpreting study results. Whereas, in hypothesis testing, study results lead the reader to reject or accept a null hypothesis, in estimation the reader can assess whether a result is strong or weak, definitive or not. A confidence interval, based on the observed result and the size of the sample, is calculated. It provides a range of probabilities within which the true probability would lie 95% or 90% of the time, depending on the precision desired. It also provides a way of determining whether the sample is large enough to make the trial definitive. If the lower boundary of a confidence interval is above the threshold considered clinically significant, then the trial is positive and definitive, if the lower boundary is somewhat below the threshold, the trial is positive, but studies with larger samples are needed. Similarly, if the upper boundary of a confidence interval is below the threshold considered significant, the trial is negative and definitive. However, a negative result with a confidence interval that crosses the threshold means that trials with larger samples are needed to make a definitive determination of clinical importance.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Braitman L. E. Confidence intervals assess both clinical significance and statistical significance. Ann Intern Med. 1991 Mar 15;114(6):515–517. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-6-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulpitt C. J. Confidence intervals. Lancet. 1987 Feb 28;1(8531):494–497. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn J. N., Johnson G., Ziesche S., Cobb F., Francis G., Tristani F., Smith R., Dunkman W. B., Loeb H., Wong M. A comparison of enalapril with hydralazine-isosorbide dinitrate in the treatment of chronic congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991 Aug 1;325(5):303–310. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt G. H., Sackett D. L., Cook D. J. Users' guides to the medical literature. II. How to use an article about therapy or prevention. A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1993 Dec 1;270(21):2598–2601. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.21.2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt G. H., Sackett D. L., Cook D. J. Users' guides to the medical literature. II. How to use an article about therapy or prevention. B. What were the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1994 Jan 5;271(1):59–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High-dose acetylsalicylic acid after cerebral infarction. A Swedish Cooperative Study. Stroke. 1987 Mar-Apr;18(2):325–334. doi: 10.1161/01.str.18.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulrow C. D., Mulrow J. P., Linn W. D., Aguilar C., Ramirez G. Relative efficacy of vasodilator therapy in chronic congestive heart failure. Implications of randomized trials. JAMA. 1988 Jun 17;259(23):3422–3426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxman A. D., Cook D. J., Guyatt G. H. Users' guides to the medical literature. VI. How to use an overview. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1994 Nov 2;272(17):1367–1371. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.17.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxman A. D., Sackett D. L., Guyatt G. H. Users' guides to the medical literature. I. How to get started. The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1993 Nov 3;270(17):2093–2095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock S. J., Hughes M. D. Estimation issues in clinical trials and overviews. Stat Med. 1990 Jun;9(6):657–671. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R. Confidence intervals for reporting results of clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 1986 Sep;105(3):429–435. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-3-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]