Abstract

The hop2 mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae arrests in meiosis with extensive synaptonemal complex (SC) formation between nonhomologous chromosomes. A screen for multicopy suppressors of a hop2-ts allele identified the MND1 gene. The mnd1-null mutant arrests in meiotic prophase, with most double-strand breaks (DSBs) unrepaired. A low level of mature recombinants is produced, and the Rad51 protein accumulates at numerous foci along chromosomes. SC formation is incomplete, and homolog pairing is severely reduced. The Mnd1 protein localizes to chromatin throughout meiotic prophase, and this localization requires Hop2. Unlike recombination enzymes such as Rad51, Mnd1 localizes to chromosomes even in mutants that fail to initiate meiotic recombination. The Hop2 and Mnd1 proteins coimmunoprecipitate from meiotic cell extracts. These results suggest that Hop2 and Mnd1 work as a complex to promote meiotic chromosome pairing and DSB repair. The identification of Hop2 and Mnd1 homologs in other organisms suggests that the function of this complex is conserved among eukaryotes.

Meiosis is a special type of cell division cycle that produces haploid gametes from diploid parental cells. At the first nuclear division of meiosis, sister chromatids remain associated, while homologous chromosomes segregate to opposite poles of the spindle apparatus. This reductional chromosome segregation is preceded by a lengthy prophase during which homologous chromosomes pair with each other, undergo high levels of genetic recombination, and engage in synaptonemal complex (SC) formation. These interactions between homologs are necessary prerequisites to the correct segregation of chromosomes at meiosis I.

Meiotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and other organisms initiates with double-strand breaks (DSBs), which are catalyzed by a topoisomerase-like protein known as Spo11 (21). DSBs are processed to expose single-stranded tails with 3′ termini (6, 44), which invade homologous sequences in nonsister chromatids (5, 31, 40). Strand invasion results in the formation of joint molecules, whose resolution gives rise to crossover and noncrossover products (2, 18, 39). In budding yeast, several proteins are required for efficient strand invasion, but the RecA homolog Rad51 is thought to provide the principal strand-exchange activity (45; reviewed in reference 30). Rad51 and accessory proteins accumulate at discrete foci on meiotic chromosomes, during the period of DSB repair (4, 14).

Meiotic cell cycle progression is tightly coupled to the status of meiotic recombination events. If DSBs are formed but their subsequent repair is prevented by mutation, then a cell cycle checkpoint (the pachytene checkpoint) causes cells to arrest in mid-meiotic prophase (reviewed in reference 3). This arrest can be alleviated by a second mutation that prevents DSB formation; for example, a spo11 mutation restores sporulation in dmc1 and hop2 strains that normally arrest with hyperresected but unrepaired DSBs (6, 23). Thus, recombination intermediates appear to act as signals that trigger the pachytene checkpoint.

In budding yeast, meiotic recombination is concurrent with chromosome synapsis (reviewed in reference 36). Early in SC formation, each chromosome develops a dense proteinaceous core that is shared by sister chromatids. Within the context of mature SC, these chromosome cores, called lateral elements, are connected to each other along their lengths by the central region of the SC. The Zip1 protein is a major building block of the SC central region (11, 46, 50). At pachytene, when chromosomes are fully synapsed, Zip1 localizes along the full length of each chromosome pair. Several observations indicate that Zip1 assembly initiates at the sites of meiotic recombination events (1, 10, 29, 35).

Proper SC formation requires pairing between homologous chromosomes. Homolog pairing occurs prior to synapsis and is largely independent of meiotic recombination (25, 28, 53). The molecular mechanism of pairing is poorly understood. At least in budding yeast, pairing involves a genome-wide homology search and unstable interactions between homologs at multiple and variable sites along their length (16, 53). The pairing machinery must be able to distinguish genuine homologs from homologous sequences dispersed among nonhomologous chromosomes (e.g., transposable elements).

A previous study reported identification of the budding yeast HOP2 gene (23). In the absence of Hop2, pairing is substantially decreased, and there is extensive synapsis between nonhomologous chromosomes. DSBs remain unrepaired, and cells arrest at the pachytene checkpoint. The meiosis-specific Hop2 protein localizes to chromosomes even in the absence of recombination initiation. The phenotype of the hop2 mutant suggests that Hop2 facilitates homologous pairing and/or prevents SC formation between nonhomologous chromosomes.

In an attempt to understand better the molecular mechanism of Hop2 action, we set out to identify proteins that interact physically with Hop2. We recovered the MND1 gene in a screen for genes whose overexpression can suppress the hop2 defect in viable spore production. MND1 was first identified by Rabitsch et al. (32) in a screen for genes expressed specifically in meiotic cells. They found that disruption of MND1 results in a failure of meiotic nuclear division and a defect in SC formation. In this paper, we demonstrate that the Mnd1 and Hop2 proteins work together as a complex that promotes homologous chromosome pairing and meiotic DSB repair. The existence of homologs of Hop2 and Mnd1 in other eukaryotes suggests that the function of this complex is conserved across species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains.

Most of the strains used are diploids in which both parents are isogenic with the haploid strain BR1919-8B (33, 35). This diploid, called TBR001, is MATa/MATα and homozygous for his4-260 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 trp1-289 ade2-1 thr1-4. A subset of the TBR001 derivatives used are heteroallelic at HIS4 (his4-260/his4-Hpa). Isogenic derivatives of TBR001 were constructed by mating appropriate haploids; isogenic haploids were generated by either transformation or genetic crosses.

TBR165 was used to screen for novel hop2 alleles. TBR165 consists of a MATa hop2::ADE2 derivative of BR1919-8B mated to a MATα strain carrying his4-Hpa leu2 ura3 ade2 trp1 thr1-4 can1 cyh2. TBR168 was used to screen for hop2-ts suppressors. TBR168 was derived from TBR165 by transformation with PCR-mutagenized HOP2 DNA as described below.

SK1 strain HTY525 (48) was used to isolate meiotic RNA for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

Strains used for the physical recombination assay are isogenic derivatives of TBR266. TBR266 consists of a MATa his4-Hpa version of BR1919-8B mated to a MATα haploid strain that carries a circular version of chromosome III and is his4-260 leu2::arg4-8-CUP1 CEN3::TRP1 ura3 ade2 trp1 thr1-4 lys2 spo13::LEU2 arg4Δ cup1Δ (34).

Generation of the hop2-ts allele.

To generate novel HOP2 alleles, the HOP2 gene was amplified by PCR using Taq polymerase and primers 10 (5′-GAACTGACCAGGCTCTATTTGAAAGATATG-3′) and 12 (5′-TTAATTAACCCGGGGATCCGCCCAAGTTTCCATTTCATCGTTCG-3′). In parallel, the TRP1 cassette in pFA6a-TRP1 (26) was amplified using primers 13 (5′-CGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA-3′) and 14 (5′-ACAACTAGCAAAGGCAGCCCCATAAACACACAGTATGTTTTTTGAGCCTTCCCCGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC-3′). In addition to containing sequences complementary to TRP1, primer 14 contains (at its outside end) DNA complementary to sequences downstream of the chromosomal HOP2 gene. The two PCR products were mixed and joined together by amplification with primers 10 and 14. This recombinant PCR product was used to transform yeast strain TBR165 selecting for Trp+ Ade+ transformants. Transformants were screened by replica plating to sporulation medium at different temperatures (23, 30, and 33°C) and then replica plating to medium containing canavanine and cycloheximide (43) to select for viable spores. The parental diploid is heterozygous for the recessive drug resistance markers can1 and cyh2 and is therefore sensitive to both drugs. However, one quarter of the viable spores produced are can1 cyh2 and therefore able to grow in the presence of both canavanine and cycloheximide.

Screening for multicopy suppressors of the hop2-ts allele.

To screen for multicopy suppressors of hop2-ts, TBR168 was transformed with a yeast genomic library in YEp24 (8). Transformants were sporulated at 33°C and then replica plated to medium containing canavanine and cycloheximide.

Gene disruption and tagging.

Plasmids for introducing the following gene disruptions were described previously: hop2::ADE2 (17), ndt80::LEU2 (49), and spo11::ADE2 (12). The his4-Hpa mutation was introduced by two-step transplacement using pV131 (51).

The mnd1::TRP1 and mnd1::kanMX mutations were engineered by PCR-mediated gene disruption (52). To generate mnd1::TRP1, the TRP1 cassette in pFA6a-TRP1 (26) was amplified and used to replace the entire YGL183c open reading frame (ORF), including the start and stop codons. To generate mnd1::kanMX, the kanMX cassette in pFA6a-GFP(S65T)-kanMX6 (26) was used to replace the entire second exon in the MND1 ORF including the stop codon.

Replicating plasmids containing the MND1 gene or MND1 cDNA were constructed as follows. Primers 49 (5′-CGGGATCCCCTCTTCTCACGAAGGCACGC-3′) and 45 (5′-GGTCGGGTTTCCCGATCTGG-3′) were used to amplify a fragment containing MND1; the PCR products were then cut with BamHI and SalI and cloned into the corresponding sites in YEplac195 (15) or YCplac33 (15) to make YEp-MND1 or YCp-MND1, respectively. To generate MND1 cDNA, the two exons were amplified separately and then recombined. The upstream exon was amplified with primers 49 and 62 (5′-GATACTGTCTGTCTCTTTGGCCCCATTGTTGAATGTTTATGATACTACACATAAAG-3′); the downstream exon was amplified with primers 45 and 63 (5′-GGGCCAAAGAGACAGACAGTATC-3′). The two PCR products were then combined and amplified with primers 49 and 45. The resulting fragment was cut with BamHI and SalI and cloned into YCplac33 (15) to make YCp-cMND1.

To generate MND1-GFP, the GFP-kanMX cassette in pFA6a-GFP(S65T)-kanMX6 was inserted just before the MND1 stop codon. Transformants were selected on medium containing G418 (26). A diploid homozygous for MND1-GFP shows wild-type spore viability, demonstrating that Mnd1-GFP is fully functional.

Sequences encoding three copies of the myc epitope were inserted between the second and third codons of the HOP2 gene as described previously (38). The spore viability of a HOP2-myc homozygous diploid is close to that of wild type (∼80% viable spores), and the localization of the protein is consistent with data obtained previously using anti-Hop2 antibodies (23). Furthermore, diploids homozygous for both HOP2-myc and MND1-GFP display the same spore viability as that of HOP2-myc alone.

A YEp24 derivative carrying HOP2 was recovered in the course of screening for hop2-ts suppressors; the presence of HOP2 was confirmed by PCR. The hop2::kanMX mutation was generated by PCR-mediated gene disruption (52); the kanMX cassette in pFA6a-GFP(S65T)-kanMX6 (26) was used to replace the entire HOP2 ORF including the start and stop codons.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from HTY525 yeast cells after 5 h in sporulation medium using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). RT-PCR was performed using the GeneAmp Gold RNA PCR reagent kit (PE Biosystems). RNA was reverse transcribed using primer 54 (5′-CGATCATGGGTGAGATTCCGC-3′). The resulting cDNA was amplified using primers 54 and 55 (5′-TGTGTAGTATCATAAACATTCAACAATG-3′). The PCR product was used directly for sequencing with the same primers to determine intron-exon junctions.

Cytology.

Surface-spread meiotic chromosomes were prepared, and immunostaining and fluorescent in situ hybridization were carried out as described previously (10, 46). The hybridization probes used to assay homolog pairing are 15 to 25 kbp in length and correspond to sequences located near the middle of the left arms of chromosomes III and V (10). Rabbit anti-Rad51 antibody was used at a 1:400 dilution (42). Mouse monoclonal anti-myc antibody 9E10 (Covance) was used at a 1:100 dilution. Rabbit and guinea pig anti-green fluorescent protein (anti-GFP) antibodies and mouse anti-Zip1 antibody have been described previously (41, 46).

Meiotic nuclear division was measured as described previously (23).

Protein analysis.

Methods described previously (49) were used for preparation of meiotic cell extracts, immunoprecipitations, and Western blot analysis, with the following modifications. For Western blot analysis, mouse monoclonal anti-myc antibody and rabbit anti-GFP antibody were used at a 1:1,000 dilution. Mouse monoclonal anti-myc and guinea pig anti-GFP antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation at a 1:200 dilution. Extracts were prepared after 16 h in sporulation medium.

Sequence analysis.

Alignment of Mnd1 homologs and shading (see Fig. 2B) were performed with ClustalW 1.7 and Boxshade 2.11 programs, respectively, available at the BCM Search Launcher (http://searchlauncher.bcm.tmc.edu/). Coiled-coil regions were predicted using the COILS program (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/COILS_form.html).

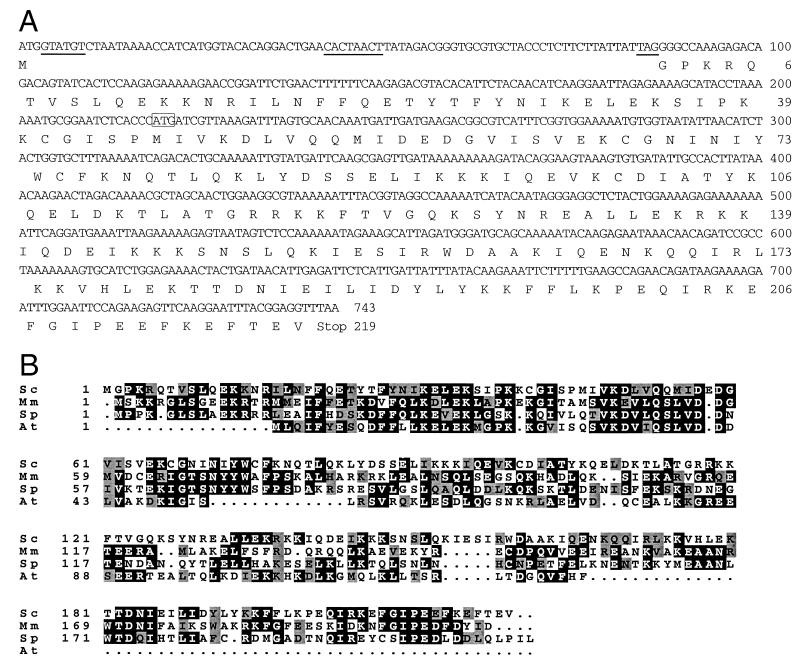

FIG. 2.

DNA and amino acid sequences of MND1 and alignment of potential Mnd1 homologs. (A) DNA sequence and encoded amino acid sequence of MND1. Consensus splicing signals (37) are underlined. The start codon of the YGL183 ORF is boxed. (B) Mnd1 of budding yeast is aligned with potential homologs from other organisms: S. cerevisiae (Sc); Mus musculus (Mm; accession no. BAB27765); S. pombe (Sp; accession no. Q09739); and Arabidopsis thaliana (At; accession no. T08972). Identical amino acids are boxed in black; similar amino acids are boxed in gray.

Physical recombination assay.

Detection of physical recombinants was carried out as described in reference 1.

RESULTS

Identification of a multicopy suppressor of a non-null allele of HOP2.

To generate a non-null allele of HOP2 to use in screening for suppressors, the HOP2 gene was randomly mutagenized by amplification by PCR. Prospective mutants were introduced into yeast, and the resulting transformants were screened for the production of viable meiotic progeny after incubation in sporulation medium (see Materials and Methods). One of the HOP2 allele mutants identified, called hop2-ts, produces abundant viable spores at 23°C but fails to sporulate at 33°C (Fig. 1A). DNA sequence analysis indicates that the hop2-ts mutation changes the leucine at position 132 to a proline; this mutation lies in a region of the protein predicted to form an α-helical coiled coil (7).

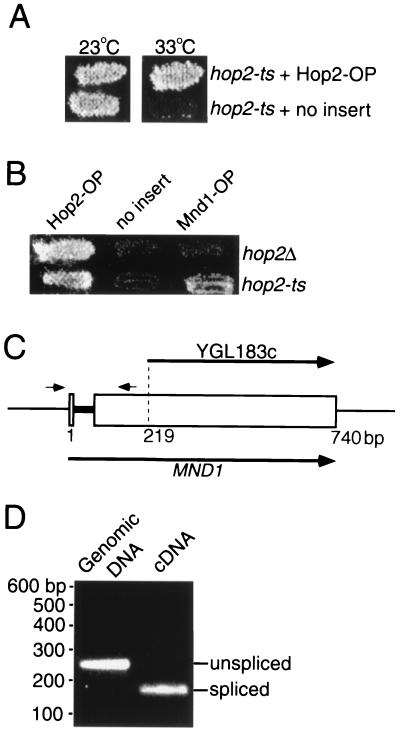

FIG. 1.

Suppression effect of Mnd1 overproduction and splicing of MND1 pre-mRNA. (A) The hop2-ts mutant (hop2-ts/hop2::ADE2) carrying the multicopy vector YEp24 containing either HOP2 or no insert was sporulated at permissive (23°C) and restrictive (33°C) temperatures and then replica plated to medium selecting for viable spores. OP, overproduction. (B) The hop2-ts mutant (hop2-ts/hop2::ADE2) and an isogenic hop2::ADE2 homozygote (referred to as hop2Δ) were transformed with YEp24 containing HOP2, MND1, or no insert. Transformants were sporulated at the restrictive temperature (33°C) for hop2-ts and then replica plated to medium selecting for viable spores. (C) Structure of the YGL183c and MND1 ORFs. The gray bar indicates the MND1 intron. The small arrows indicate the locations of the primers used to generate the PCR products shown in panel D. (D) Genomic DNA and cDNA derived from meiotic mRNA were amplified by PCR with primers flanking the putative intron (as shown in panel C). The positions of molecular size markers are indicated on the left.

In an attempt to identify genes that interact with HOP2, a yeast genomic library was screened for genes whose overexpression can suppress the hop2-ts defect in viable spore production at 33°C (see Materials and Methods). Subcloning of a recovered plasmid demonstrated that suppressor activity (Fig. 1B) requires ORF YGL183c, also known as the MND1 gene (32; http://genome-www.stanford.edu/Saccharomyces/). A multicopy plasmid carrying YGL183c suppresses the hop2-ts defects in spore formation and viable spore production (Fig. 1B); sporulation efficiency is 5%, and spore viability is 82%. Multicopy YGL183c does not suppress a hop2-null mutant (Fig. 1B), demonstrating that overexpression does not simply bypass the requirement for Hop2.

The MND1 gene contains an intron.

Rabitsch et al. (32) assumed that the MND1 gene is contained entirely within the YGL183c ORF. However, a plasmid containing all of YGL183c plus 302 bp of upstream and 622 bp of downstream sequence does not suppress hop2-ts, suggesting that the ORF identified in the course of yeast genome sequencing is incomplete. One possibility is that the suppressor gene contains an intron and YGL183c corresponds to sequences from only one exon. To investigate this possibility, the sequences surrounding YGL183c were examined for the presence of splicing signals (37). In this manner, a putative intron defined by consensus 5′ and 3′ splice sites, and containing a consensus branch point sequence, was found approximately 200 bp upstream of the YGL183c start codon (Fig. 1C and 2A). To determine whether this intron is utilized, mRNA from meiotic cells was reverse transcribed, and the resulting cDNA was amplified by PCR using primers flanking the putative intron. The DNA amplified from cDNA was found to be smaller than the DNA amplified from genomic DNA (Fig. 1D), indicating that the mRNA is indeed spliced. Sequencing of the amplified cDNA confirmed that the 5′ and 3′ splice sites identified by sequence inspection are used as splice junctions (Fig. 2A). Based on this analysis, the MND1 gene consists of not only YGL183c but also an upstream exon. A plasmid containing the intronless version of MND1 fully complements the mnd1 defects in meiosis (Table 1; see below), indicating that this version of the gene encodes a functional Mnd1 protein.

TABLE 1.

Nuclear division, sporulation, and spore viability in meiotic mutants

| Genotypea | Nuclear division (%)b | Spore formation (%)b | Spore viability (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| mnd1::kanMX + YCp | NDd | 1.7 | ND |

| mnd1::kanMX + YCp-MND1 | ND | 61.0 | 97 |

| mnd1::kanMX + YCp-cMND1 | ND | 67.4 | 92 |

| Wild type | 66.8 | 68.0 | 98 |

| hop2::ADE2 | 0.6 | 1.3 | ND |

| mnd1::TRP1 | 0.5 | 1.5 | ND |

| spo11::ADE2 | ND | 50.7 | ND |

| spo11::ADE2 hop2::ADE2 | ND | 50.0 | ND |

| spo11::ADE2 mnd1::TRP1 | ND | 48.6 | ND |

All strains are homozygous diploids isogenic with TBR001. The MND1 gene and MND1 cDNA were introduced on the centromere-containing plasmid YCplac33.

To measure nuclear division and spore formation, cells were scored after 48 h in sporulation medium; at least 400 cells were counted for each strain. Meiotic nuclear division and spore formation were measured in separate experiments.

To generate spore viability data, at least 22 tetrads were dissected for each strain.

ND, not determined.

Transcription of the YGL183c ORF (and presumably the MND1 gene) is induced during meiotic prophase, with timing similar to that of HOP2 (9, 32). The carboxy-terminal two-thirds of the Mnd1 protein has a high probability of forming a coiled coil (amino acids 85 to 190, with an interruption from amino acids 115 to 125). A database search identified similar proteins from fission yeast, Arabidopsis, and mice, suggesting that Mnd1 plays a conserved role in meiosis across species (Fig. 2B).

The mnd1 mutant arrests in meiotic prophase.

To understand the function of MND1, the gene was disrupted and the resulting phenotype was characterized. When diploids homozygous for a mnd1-null mutation are introduced into sporulation medium, they fail to make tetrads (Table 1). To determine the stage at which the mnd1 mutant is defective, cells were stained with a DNA-binding dye (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole [DAPI]) and viewed in the fluorescence microscope. Almost all cells (99%) in the mutant remain mononucleate, even at late time points when the wild type has completed sporulation (Table 1). Thus, mnd1 cells arrest in meiotic prophase.

Previous studies have shown that the pachytene checkpoint causes meiotic cells to arrest in mid-meiotic prophase if DSBs remain unrepaired (reviewed in reference 3). If cell cycle arrest in the mnd1 strain is due to this checkpoint, then arrest should be alleviated by introduction of a spo11 mutation to prevent the formation of meiotic DSBs. Indeed, mnd1 spo11 cells are able to complete meiosis and form spores (Table 1), as is the case for the hop2 spo11 double mutant (Table 1) (23).

Chromosomes are incompletely synapsed in the absence of Mnd1.

To examine the effect of mnd1 on chromosome synapsis, meiotic nuclei were surface spread and stained with DAPI and antibodies to the Zip1 protein. Analysis of mnd1 cells at different time points indicated that Zip1 localization is maximal at late times, after most wild-type cells have completed nuclear division (data not shown). To quantitate synapsis, cells were harvested after 28 h in sporulation medium when most mnd1 (and hop2) cells had arrested. As a positive control, an ndt80 strain was analyzed. The ndt80 mutant undergoes normal SC formation but then arrests at pachytene with fully synapsed chromosomes (55). Nuclei were classified into three categories based on the pattern of Zip1 staining (Fig. 3A). In nuclei with “dotty” Zip1 staining, Zip1 localizes to foci on chromosomes, representative of the initiation of SC formation. Nuclei with “dotty-linear” Zip1 staining, which is indicative of partial synapsis, display a number of linear stretches of Zip1 staining in addition to Zip1 foci. In nuclei with “linear” Zip1 staining, Zip1 is localized along the full length of each chromosome pair, indicating full synapsis.

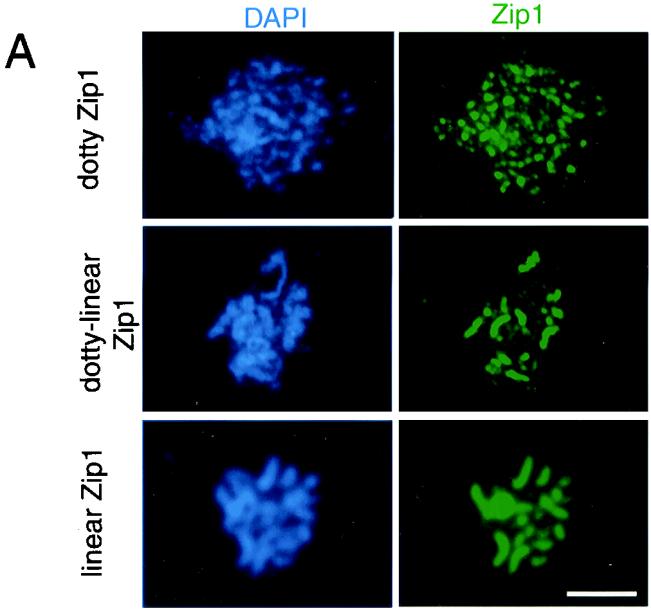

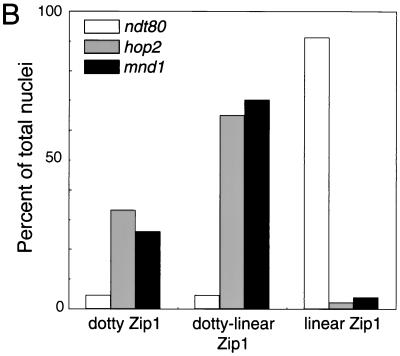

FIG. 3.

Chromosome synapsis is aberrant in mnd1 mutants. (A) Spread nuclei from mnd1 mutants were stained with DAPI and anti-Zip1 antibodies. Examples of different patterns of Zip1 staining are shown. (B) Quantitative analysis of spread nuclei according to the pattern of Zip1 localization. Samples were collected after 28 h in sporulation medium. At least 100 nuclei were scored for each strain. Strains used were ndt80::LEU2, hop2::ADE2, and mnd1::kanMX; all are homozygous diploids isogenic with TBR001. Bar = 5 μm.

After 28 h of sporulation of the ndt80 strain, about 90% of cells display full synapsis (Fig. 3B). In contrast, in mnd1 and hop2 strains, very few cells have fully synapsed chromosomes. Instead, about two-thirds of the nuclei exhibit dotty-linear Zip1 staining, while the remaining one-third display dotty Zip1 localization (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, most nuclei from mnd1 (53%) and hop2 (55%) strains contain a polycomplex, an aggregate of Zip1 protein that is unassociated with chromosomal DNA. In contrast, only 3% of nuclei from wild type contain a polycomplex. Polycomplexes are common in mutants defective in SC formation (1, 10, 25, 29). These results demonstrate that the mnd1 mutation impairs synapsis, though it does not completely abolish SC formation.

Homolog pairing is defective in the mnd1 mutant.

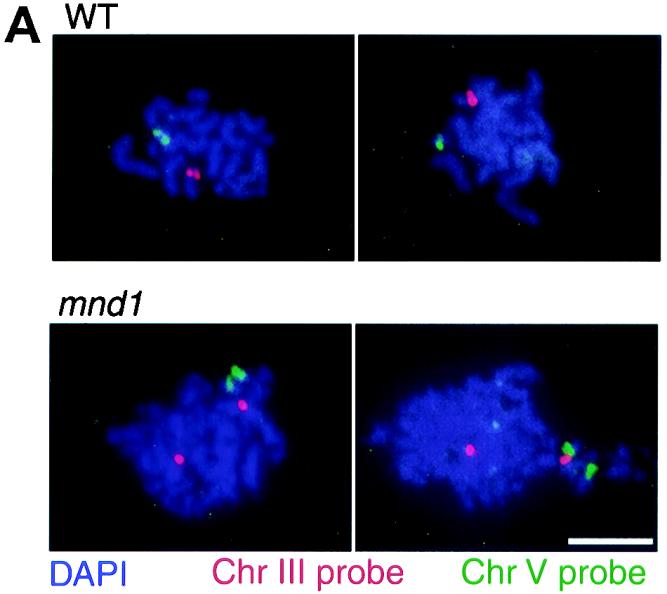

The defect in SC formation in the mnd1 mutant might reflect an underlying defect in homologous chromosome pairing, as postulated previously for the hop2 strain (23). Alternatively, chromosomes could pair but fail to synapse, as observed with several mutants including zip1 mutants (10, 25, 28, 53). To distinguish these possibilities, homolog pairing was assayed by fluorescent in situ hybridization, using chromosome-specific DNA probes to analyze spread meiotic nuclei. Hybridization of a chromosome-specific probe to a spread nucleus results in a single hybridization signal or two immediately adjacent signals (usually overlapping or touching) if homologs are paired; two separate signals result if homologs are unpaired (Fig. 4A). Nuclei were spread after 24 h in sporulation medium, and the ndt80 mutant was used as a control.

FIG. 4.

Homolog pairing is defective in mnd1 mutants. (A) Typical images of fluorescent in situ hybridization in wild-type (WT) and mnd1 strains are shown. (B) Quantitative analysis of homolog pairing. For each strain, 120 nuclei were scored after 24 h in sporulation medium. Strains used were ndt80::LEU2, hop2::ADE2, mnd1::kanMX, and hop2::ADE2 mnd1::kanMX; all are homozygous diploids isogenic with TBR001. Shown is the frequency of pairing for chromosomes III and V, as well as the frequency of nuclei in which both chromosomes III and V are paired. Chr, chromosome. Bar = 5 μm.

In ndt80 cells, both chromosomes III and V are paired in almost all nuclei (Fig. 4B). In contrast, in the mnd1 mutant, chromosome III is paired in only ∼30% of nuclei, and a similar frequency is observed for chromosome V. The frequency of mnd1 nuclei in which both chromosomes III and V are paired is only ∼10%, which is approximately the frequency expected if pairing of chromosome III and that of chromosome V are independent events.

The ability to suppress the hop2-ts allele by Mnd1 overproduction suggests that Hop2 and Mnd1 act in the same pathway. If so, then a hop2 mnd1 double mutant should display a defect in pairing similar to that of the two single mutants. In contrast, if the hop2 and mnd1 mutations affect pairing through different mechanisms, then these mutations should have additive (or synergistic) effects on homolog pairing. As shown in Fig. 4B, the double mutant behaves similarly to the two single mutants, indicating that HOP2 and MND1 are in the same epistasis group with respect to pairing.

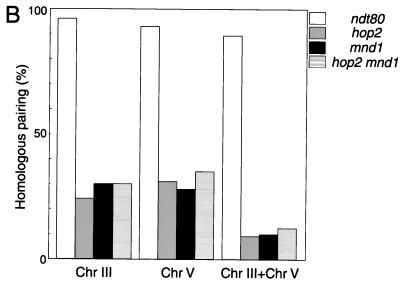

The formation of mature recombinants is defective in the mnd1 mutant.

To investigate the involvement of Mnd1 in meiotic recombination, the formation of mature recombinants was assayed physically in diploid strains carrying one linear and one circular copy of chromosome III (13). A single crossover between one linear and one circular chromatid results in production of a linear dimer. A double crossover involving one linear chromatid and both chromatids of the circular chromosome generates a linear trimer. The linear monomers, dimers, and trimers can be separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (circular chromosomes do not enter the gel). In wild type, after 45 h of sporulation, 57% of total DNA entering the gel was recombinant (Fig. 5A). In the mnd1 mutant, the band representing the linear monomer was very diffuse, with a substantial amount of DNA migrating faster than the intact monomer (Fig. 5A). These fragments of lower molecular weight represent molecules resulting from double-strand breakage, and their persistence indicates that the mnd1 mutant is defective in DSB repair. Consistent with this interpretation, the mnd1 mutant produced only a small amount of linear dimers and trimers (8% of total DNA), and these did not appear until much later than their wild-type counterparts (Fig. 5A). A small amount of recombinant DNA (7% of total) was also detected in hop2 (Fig. 5A), in contrast to a previous report that used a less sensitive assay and failed to detect crossover products (23).

FIG. 5.

Meiotic recombination is impaired in mnd1. (A) Diploids containing one circular and one linear copy of chromosome III were introduced into sporulation medium, and samples were harvested at the time points indicated. The lane labeled 45* represents a shorter exposure of the 45-h sample from wild type (WT). (B) Cells were incubated in sporulation medium for 20 h and then subdivided. One subculture was further incubated in sporulation medium (SPM), and aliquots were harvested after 5 and 10 h. The other subculture was transferred to vegetative growth medium and incubated for an additional 5 h. Genomic DNA was subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis followed by Southern blot analysis hybridizing with a probe containing the THR4 gene on chromosome III. Strains used were wild type, mnd1::TRP1/mnd1::kanMX, and hop2::ADE2/hop2::kanMX; all strains are isogenic with TBR266.

When mnd1 cells are incubated in sporulation medium for 20 h and then transferred to rich medium to permit vegetative growth, the fragments indicative of DSBs disappear (Fig. 5B). Thus, the defect in DSB repair in mnd1 strains is restricted to meiotic cells. Despite efficient DSB repair after the return to vegetative growth, only a small fraction (3%) of DNA is found as linear dimers and trimers, indicating that DSB repair by interhomolog crossing over is infrequent.

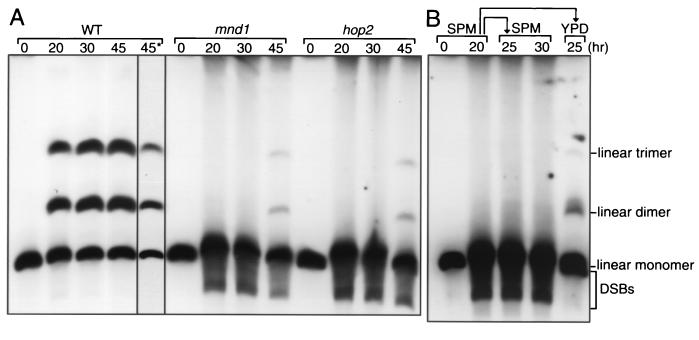

Rad51 foci accumulate on chromosomes in the mnd1 mutant.

To investigate further the recombination defect in the mnd1 mutant, the Rad51 strand-exchange protein was immunolocalized in spread nuclei. In wild type, Rad51 is present as numerous foci on chromosomes at the leptotene (dotty Zip1 staining) and zygotene (dotty-linear Zip1) stages, but these foci largely disappear by pachytene (linear Zip1) (Fig. 6A) (4). The mnd1 mutant is similar to wild type at leptotene (Fig. 6B). However, at zygotene, Rad51 foci are more numerous and more intensely stained than are their wild-type counterparts (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, Rad51 staining persists throughout pachytene; at this stage, Rad51 no longer appears as discrete foci, perhaps because chromosome condensation brings the foci closer together (Fig. 6B). The difference between wild type and mutant is most pronounced at late time points (Fig. 6C), when most mutant cells have undergone cell cycle arrest. After 28 h in sporulation medium, 70 to 80% of nuclei from the mutants contain more than 10 Rad51 foci, compared to only ∼10% in wild type (and also the ndt80 strain [data not shown]). Thus, the defect in recombination in mnd1 (and hop2) strains occurs after the localization of Rad51 to chromosomes.

FIG. 6.

Rad51 foci accumulate on meiotic chromosomes in mnd1. Spread meiotic nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue) and antibodies to Rad51 (green) and Zip1 (red). Shown are spread nuclei from wild type (A) and the mnd1-null mutant (B). Arrowheads indicate the position of a polycomplex. (C) The fraction of nuclei with more than 10 Rad51 foci was scored at various time points after the introduction into sporulation medium. Note that cells do not proceed through meiosis with perfect synchrony; thus, a small fraction of wild-type cells are at the zygotene stage even at late time points. Strains analyzed were wild type, hop2::ADE2, and mnd1::TRP1; all strains are homozygous diploids isogenic with TBR001. WT, wild type. Bar = 5 μm.

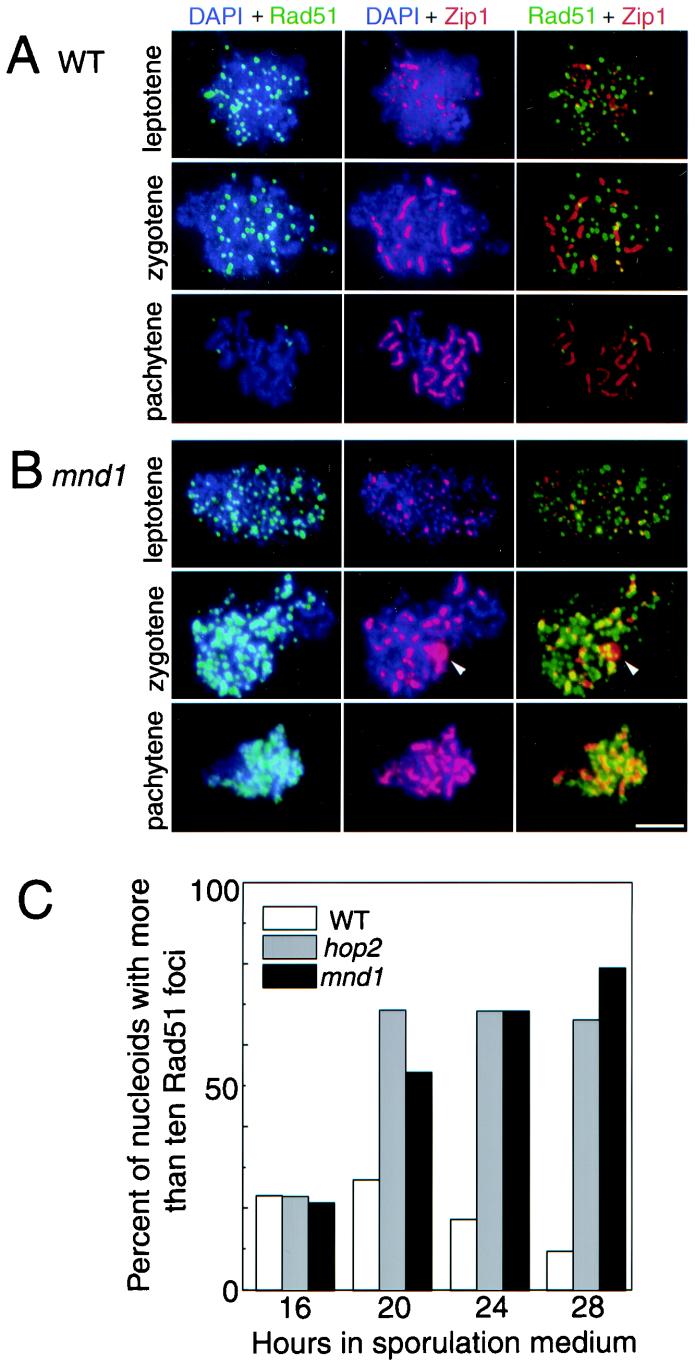

Mnd1 localizes to chromosomes throughout meiotic prophase, and this localization requires Hop2.

To determine the in vivo location of Mnd1, the protein was tagged with GFP and immunolocalized in spread meiotic nuclei. Cells at different stages of meiotic prophase were identified based on the pattern of Zip1 staining. Extensive localization of Mnd1 to chromosomes was observed from leptotene through pachytene (Fig. 7A). There is no detectable Mnd1 on chromosomes from vegetative cells (data not shown).

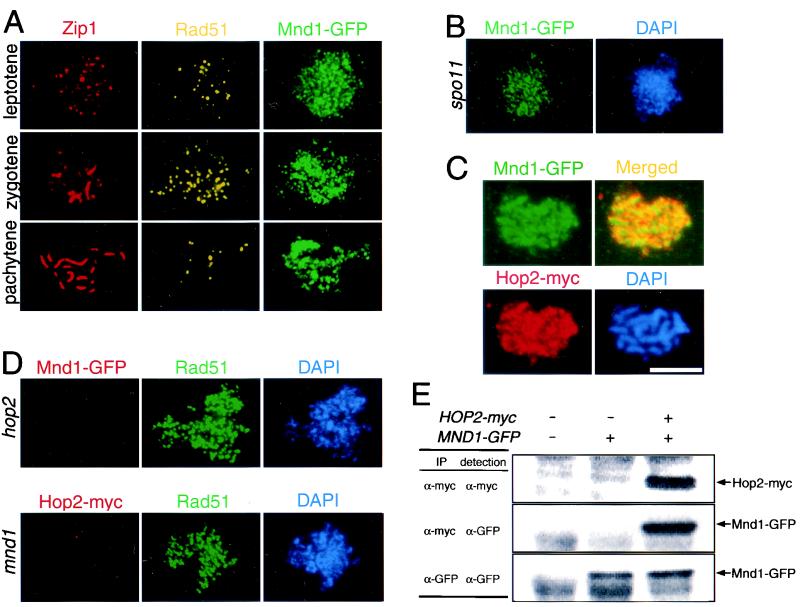

FIG. 7.

Localization of Mnd1 to meiotic chromosomes and coimmunoprecipitation of Mnd1 and Hop2. (A) Meiotic chromosomes from cells producing Mnd1 tagged with GFP were stained with anti-Zip1, anti-Rad51, and anti-GFP antibodies. (B) Nuclei from spo11 cells producing Mnd1-GFP were stained with anti-GFP antibodies and DAPI. (C) Nuclei from cells producing myc-tagged Hop2 and GFP-tagged Mnd1 were stained with anti-myc and anti-GFP antibodies. Areas of overlap appear yellow in the merged image. (D) Shown in the top row is a nucleus from a hop2-null mutant producing GFP-tagged Mnd1 after staining with anti-GFP and anti-Rad51 antibodies and with DAPI. Shown on the bottom is a nucleus from a mnd1-null mutant producing myc-tagged Hop2 after staining with anti-myc and anti-Rad51 antibodies and with DAPI. (E) Extracts from meiotic cells containing untagged Hop2 and Mnd1, tagged Mnd1 only, or tagged versions of both Hop2 and Mnd1 were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-myc or anti-GFP antibodies. Antibodies used for precipitation are indicated under “IP”; antibodies used for Western blot analysis are indicated under “detection.” Strains used were wild type, spo11::ADE2 MND1-GFP, MND1-GFP, HOP2-myc MND1-GFP, hop2::ADE2 MND1-GFP, and mnd1::TRP1 HOP2-myc; all strains are homozygous diploids isogenic with TBR001. Bar = 5 μm.

In light of the mnd1 defect in meiotic recombination, it is possible that Mnd1 functions at the sites of meiotic recombination events. To investigate this possibility, the localization pattern of Mnd1 was compared to that of Rad51. Mnd1 loads onto chromosomes earlier and remains later than does Rad51; Rad51 staining is most intense in zygotene, but Mnd1 staining is similar in intensity from leptotene through pachytene (Fig. 7A). Also, whereas Rad51 localizes to discrete foci, Mnd1 staining is more diffuse and continuous (Fig. 7A). Finally, localization of Rad51 to chromosomes requires DSBs (4), but Mnd1 localizes to chromosomes even in a spo11 mutant (Fig. 7B).

The localization of Hop2 and that of Mnd1 were also compared. These proteins display similar patterns of staining, both spatially and temporally (Fig. 7C) (23; data not shown), and double staining indicates significant overlap between the two (Fig. 7C). However, since both proteins localize all over chromatin, the overlap observed does not necessarily indicate an interaction between the two proteins. Importantly, however, localization of Mnd1 to chromosomes requires Hop2, and localization of Hop2 requires Mnd1 (Fig. 7D).

The Mnd1 and Hop2 proteins coimmunoprecipitate from meiotic cell extracts.

To investigate further the relationship between Hop2 and Mnd1, the proteins were immunoprecipitated from meiotic cell extracts and the precipitates were analyzed by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 7E, when Hop2 protein tagged with the myc epitope is precipitated with anti-myc antibodies, the Mnd1-GFP fusion protein is also present in the precipitate. Recovery of Mnd1-GFP with anti-myc antibodies depends on the presence of Hop2-myc. These results argue that Hop2 and Mnd1 are part of the same protein complex.

DISCUSSION

The mnd1 mutant is defective in meiotic interhomolog interactions.

Our analysis indicates that the mnd1 mutant has a constellation of phenotypes similar to those of the hop2 mutant. In both cases, meiotic cells arrest at the pachytene checkpoint with unrepaired DSBs and abundant Rad51 foci on chromosomes. In addition, homolog pairing is defective and SC formation is impaired. The Mnd1 protein localizes to chromosomes from leptotene through pachytene, suggesting a direct involvement in mediating interhomolog interactions.

Mnd1 is defective in meiotic recombination.

A physical recombination assay demonstrates that most DSBs remain unrepaired in mnd1 and hop2 mutants. However, a small amount of crossover product is generated in both mutants; in each case, mature recombinants are decreased about eightfold. The reduction in mature recombinants cannot be an indirect consequence of cell cycle arrest, because Leu and Roeder (24) showed that DSBs remain unrepaired in hop2 strains even when the pachytene checkpoint is inactivated by a swe1 mutation.

In wild type, the average number of crossovers on chromosome III is three; the eightfold reduction observed for hop2 and mnd1 mutants should thus result in ∼0.4 crossovers per chromosome III bivalent. It is therefore surprising that the relative abundance of linear trimers compared to linear dimers is similar in wild type and the mutants. Linear trimers result only from double and higher-order exchanges, whereas linear dimers can result from single crossovers (as well as higher-order exchanges). Furthermore, only one quarter of double crossovers generate a linear trimer. Thus, given the low frequency of crossing over, linear trimers are expected to be rare in the mutants (as is the case in the return-to-growth experiment). The higher-than-expected abundance of trimers in meiotic cells suggests that a subset of mnd1 (and hop2) cells are competent to undergo recombination on chromosome III, and these undergo nearly wild-type levels of crossing over. Most of the rest of the population is presumably incompetent for recombination on this chromosome. In light of the homolog pairing data presented above, it seems likely that the subset of cells in which chromosome III is paired accounts for most or all of the recombination observed, while the cells in which chromosome III is unpaired produce few or no recombinants.

When mnd1 cells are incubated in sporulation medium to induce meiotic DSBs and then returned to growth medium, the DSBs are repaired. Thus, the defect in DSB repair is specific to meiotic cells. Despite efficient DSB repair, few crossover products are generated in the return-to-growth protocol. It is likely that most DSBs are repaired by sister chromatid exchange (which would not be detected in the physical assay) because this is the preferred mode of repair in vegetative cells (20). In meiotic cells, exchange between sisters is inhibited (5, 31, 40); this inhibition would be relieved when cells return to the mitotic cell cycle. It is also possible that some DSBs are repaired by interhomolog recombination events that are resolved as noncrossover products; indeed, the fraction of DSB repair events associated with crossing over is much lower in vegetative cells than in meiotic cells (reviewed in reference 30).

Cytological analysis indicates that the Rad51 protein accumulates on chromosomes in mnd1 and hop2 strains. A previous study showed that the RecA homolog Dmc1 also persists on chromosomes in hop2 strains (23). These results indicate that the defect in recombination in mnd1 and hop2 strains occurs after the Rad51 and Dmc1 proteins normally localize to chromosomes. A previous study showed that DSBs in hop2 strains are processed to expose single-stranded tails, and these tails become longer than their wild-type counterparts (23). This is the same phenotype observed for the rad51 mutant (42), which is presumed to be defective in strand invasion in vivo based on the strand-exchange activity of the Rad51 protein in vitro (45). Thus, it seems likely that the DSBs made in mnd1 strains undergo processing but then fail to engage in strand invasion.

Although Hop2 and Mnd1 resemble the recombination proteins Rad51 and Dmc1 in many respects, it is important to note several differences. First, localization of the Rad51 and Dmc1 proteins requires DSB formation, whereas localization of Hop2 and Mnd1 is independent of the initiation of meiotic recombination. Second, the Hop2/Mnd1 complex loads onto chromosomes earlier and remains later than do Rad51 and Dmc1. Third, whereas Rad51 and Dmc1 localize to discrete foci, Hop2/Mnd1 staining is more diffuse and continuous. Fourth, the hop2- and mnd1-null mutants fail to sporulate in all yeast strains tested, whereas arrest of dmc1 and rad51 mutants depends on strain background (among the strains used for this study both rad51 and dmc1 strains sporulate). Fifth, the hop2 mutant has been shown previously to undergo nonhomologous synapsis, while the dmc1 mutant undergoes little or no SC formation between nonhomologous chromosomes (23). Finally, hop2 and mnd1 strains undergo more polycomplex formation than do rad51 and dmc1 strains (unpublished data), suggesting a more severe defect in chromosome synapsis. This comparison suggests that Hop2 and Mnd1 affect recombination through a mechanism distinct from that of the Rad51 and Dmc1 proteins.

Mnd1 and Hop2 are conserved proteins that form a complex.

A number of observations indicate that the Hop2 and Mnd1 proteins interact with each other. First, overexpression of MND1 results in allele-specific suppression of the hop2-ts phenotype. Second, epistasis analysis indicates that the two proteins participate in the same pathway or process. Third, the localization of these proteins to chromosomes is mutually dependent. Fourth, Mnd1 coimmunoprecipitates with Hop2. Finally, analysis of the Hop2 immunoprecipitate by gel electrophoresis and silver staining demonstrates that Mnd1 is the predominant protein recovered together with Hop2 (data not shown). Though these observations do not conclusively demonstrate a direct physical interaction between Mnd1 and Hop2, they argue strongly that these proteins are part of the same complex.

Both Hop2 and Mnd1 are predicted to form regions of coiled coil (7), raising the possibility that these proteins form a heterodimer held together by coiled-coil interactions. The hop2-ts mutation changes a leucine residue (Leu 132) in the middle of the coiled-coil region (amino acids 95 to 160) to a proline and is predicted to cause an interruption in the coiled coil. Thus, it is possible that the hop2-ts mutation impairs Hop2 function by destabilizing its interaction with Mnd1. Consistent with this possibility, suppression by Mnd1 overproduction is allele specific. MND1 overexpression does not suppress the hop2-null allele, nor does it suppress two other temperature-sensitive hop2 alleles (unpublished data). One of these temperature-sensitive mutations is predicted to eliminate much of the Hop2 coiled coil; in this case, the defect in the Hop2-Mnd1 interaction is probably too severe to be corrected by Mnd1 overproduction. The other temperature-sensitive mutation has no effect on the formation of coiled coil and presumably affects some other aspect of Hop2 function. It is interesting that both Hop2 (19, 27, 47) and Mnd1 (Fig. 2B) have homologs in other organisms, and these homologous proteins also have high probabilities of forming coiled coils. Thus, the Hop2/Mnd1 complex appears to be conserved across species.

What is the molecular function of the Hop2/Mnd1 complex?

A previous study showed that the hop2 mutation is unique in permitting extensive SC formation between nonhomologous chromosomes (23). We have shown that hop2 and mnd1 mutants have the same phenotype in many respects, and they are in the same epistasis group genetically. Thus, it is likely that the mnd1 mutant also undergoes SC formation between nonhomologous chromosomes. Nonhomologous synapsis can explain the reduction in SC formation. If synapsis is partially or largely nonhomologous, then chromosomes can never fully synapse. For example, two chromosomes of different lengths cannot synapse end to end. Branch points, where chromosomes switch pairing partners, are bound to have short regions of asynapsis.

Recently, Nabeshima et al. (27) reported characterization of a fission yeast null mutant null in the meu13 gene, which is homologous to HOP2. The meu13 mutant displays defects in meiotic recombination and homolog pairing similar to those reported for hop2 and mnd1 strains. However, the meu13 strain is not defective in the telomere clustering and nuclear movements required for proper homolog pairing in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (56). Thus, Meu13 must affect pairing through some other mechanism. Note that fission yeast does not make SC, suggesting that Meu13 and its homologs are not directly involved in SC formation. The aberrations in SC formation observed for hop2 and mnd1 strains, therefore, probably result from a defect in one or more processes that normally precede synapsis.

We favor the view that the Hop2/Mnd1 complex is involved in some aspect of matching homologous DNA sequences. Wild-type meiotic cells undergo a high frequency of ectopic recombination events between artificial repeats on nonhomologous chromosomes (16). These ectopic events suggest that each sequence in the genome has the potential to interact at least transiently with many other sequences in the genome. Nevertheless, chromosomes are fully synapsed with their homologs by the pachytene stage. Thus, there must exist mechanisms to discriminate homologous from nonhomologous (or ectopic) sequences and to reverse inappropriate interhomolog interactions.

Hop2 and Mnd1 could act either before or after the formation of meiotic DSBs. Analyses of chromosome pairing by fluorescent in situ hybridization indicate that homolog alignment is largely independent of DSBs (25, 28, 53). The Hop2/Mnd1 complex could act on the unstable interactions between intact DNA duplexes that occur prior to DSB induction. Alternatively, Hop2 and Mnd1 could act after DSBs are formed. The RecA-like proteins (including Rad51) have the ability to assess homology between a single-stranded DNA tail and an intact DNA duplex (54); Hop2 and Mnd1 might be meiosis-specific participants in this process. Regardless of whether Hop2 and Mnd1 act before or after DSB formation, these proteins might be involved in homology assessment or recognition. It is also possible that the Hop2/Mnd1 complex functions either to stabilize interactions between homologous allelic sequences or to dissociate inappropriate partners.

Acknowledgments

We thank Douglas Bishop and Akira Shinohara for anti-Rad51 antibodies. We are grateful to Jennifer Fung, Erica Hong, Jun-Yi Leu, and Beth Rockmill for comments on the manuscript and to Tomomi Tsubouchi for helpful discussions. The Howard Hughes Biopolymer/Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Laboratory at Yale University synthesized oligonucleotides and performed DNA sequencing analysis.

This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and by a Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad granted to H.T. by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agarwal, S., and G. S. Roeder. 2000. Zip3 provides a link between recombination enzymes and synaptonemal complex proteins. Cell 102:245-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allers, T., and M. Lichten. 2001. Differential timing and control of noncrossover and crossover recombination during meiosis. Cell 106:47-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailis, J. M., and G. S. Roeder. 2000. The pachytene checkpoint. Trends Genet. 16:395-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bishop, D. K. 1994. RecA homologs Dmc1 and Rad51 interact to form multiple nuclear complexes prior to meiotic chromosome synapsis. Cell 79:1081-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop, D. K., Y. Nikolski, J. Oshiro, J. Chon, M. Shinohara, and X. Chen. 1999. High copy number suppression of the meiotic arrest caused by a dmc1 mutation: REC114 imposes an early recombination block and RAD54 promotes a DMC1-independent DSB repair pathway. Genes Cells 4:425-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishop, D. K., D. Park, L. Xu, and N. Kleckner. 1992. DMC1: a meiosis-specific yeast homolog of E. coli recA required for recombination, synaptonemal complex formation, and cell cycle progression. Cell 69:439-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burkhard, P., J. Stetefeld, and S. V. Styrelkov. 2001. Coiled coils: a highly versatile protein folding motif. Trends Cell Biol. 11:82-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson, M., and D. Botstein. 1982. Two differentially regulated mRNAs with different 5′ ends encode secreted with intracellular forms of yeast invertase. Cell 28:145-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu, S., J. DeRisi, M. Eisen, J. Mulholland, D. Botstein, P. O. Brown, and I. Herskowitz. 1998. The transcriptional program of sporulation in budding yeast. Science 282:699-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chua, P. R., and G. S. Roeder. 1998. Zip2, a meiosis-specific protein required for the initiation of chromosome synapsis. Cell 93:349-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong, H., and G. S. Roeder. 2000. Organization of the yeast Zip1 protein within the central region of the synaptonemal complex. J. Cell Biol. 148:417-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engebrecht, J., and G. S. Roeder. 1989. Yeast mer1 mutants display reduced levels of meiotic recombination. Genetics 121:237-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Game, J. C., K. C. Sitney, V. E. Cook, and R. K. Mortimer. 1989. Use of a ring chromosome and pulsed-field gels to study interhomolog recombination, double-strand DNA breaks and sister-chromatid exchange in yeast. Genetics 123:695-713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gasior, S. L., A. K. Wong, Y. Kora, A. Shinohara, and D. K. Bishop. 1998. Rad52 associates with RPA and functions with Rad55 and Rad57 to assemble meiotic recombination complexes. Genes Dev. 12:2208-2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gietz, R. D., and A. Sugino. 1988. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene 74:527-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldman, A. S. H., and M. Lichten. 1996. The efficiency of meiotic recombination between dispersed sequences in Saccharomyces cerevisiae depends upon their chromosomal location. Genetics 144:43-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong, E.-J. E., and G. S. Roeder. 2002. A role for Ddc1 in signaling meiotic double-strand breaks at the pachytene checkpoint. Genes Dev. 16:363-376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter, N., and N. Kleckner. 2001. The single-end invasion: an asymmetric intermediate at the double-strand break to double-holliday junction transition of meiotic recombination. Cell 106:59-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ijichi, H., T. Tanaka, T. Nakamura, H. Yagi, A. Hakuba, and M. Sato. 2000. Molecular cloning and characterization of a human homologue of TBPIP, a BRCA1 locus-related gene. Gene 248:99-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadyk, L. C., and L. H. Hartwell. 1992. Sister chromatids are preferred over homologs as substrates for recombinational repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 132:387-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keeney, S. 2001. Mechanism and control of meiotic recombination initiation. Curr. Biol. 52:1-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein, F., P. Mahr, M. Galova, S. Buonomo, and K. Nasmyth. 1999. A central role for cohesins in sister chromatid cohesion, the formation of axial elements and recombination during yeast meiosis. Cell 98:91-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leu, J.-Y., P. R. Chua, and G. S. Roeder. 1998. The meiosis-specific Hop2 protein of S. cerevisiae ensures synapsis between homologous chromosomes. Cell 94:375-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leu, J.-Y., and G. S. Roeder. 1999. The pachytene checkpoint in S. cerevisiae depends on Swe1-mediated phosphorylation of the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdc28. Mol. Cell 4:805-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loidl, J., F. Klein, and H. Scherthan. 1994. Homologous pairing is reduced but not abolished in asynaptic mutants of yeast. J. Cell Biol. 125:1191-1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Phillippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nabeshima, K., Y. Kakihara, Y. Hiraoka, and H. Nojima. 2001. A novel meiosis-specific protein of fission yeast, Meu13p, promotes homologous pairing independently of homologous recombination. EMBO J. 14:3871-3881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nag, D. K., H. Scherthan, B. Rockmill, J. Bhargava, and G. S. Roeder. 1995. Heteroduplex DNA formation and homolog pairing in yeast meiotic mutants. Genetics 141:75-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novak, J. E., P. Ross-Macdonald, and G. S. Roeder. 2001. The budding yeast Msh4 protein functions in chromosome synapsis and the regulation of crossover distribution. Genetics 158:1013-1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paques, F., and J. E. Haber. 1999. Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:349-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petes, T. D., and P. J. Pukkila. 1995. Meiotic sister chromatid recombination. Adv. Genet. 33:41-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabitsch, K. P., A. Toth, M. Galova, A. Schleiffer, G. Schaffner, E. Aigner, C. Rupp, A. M. Penkner, A. C. Moreno-Borchart, M. Primig, R. E. Esposito, F. Klein, M. Knop, and K. Nasmyth. 2001. A screen for genes required for meiosis and spore formation based on whole-genome expression. Curr. Biol. 11:1001-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rockmill, B., and G. S. Roeder. 1990. Meiosis in asynaptic yeast. Genetics 126:563-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rockmill, B., and G. S. Roeder. 1998. Telomere-mediated chromosome pairing during meiosis in budding yeast. Genes Dev. 12:2574-2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rockmill, B., M. Sym, H. Scherthan, and G. S. Roeder. 1995. Roles for two RecA homologs in promoting meiotic chromosome synapsis. Genes Dev. 9:2684-2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roeder, G. S. 1997. Meiotic chromosomes: it takes two to tango. Genes Dev. 11:2600-2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rymond, R. C., and M. Rosbash. 1992. Yeast pre-mRNA splicing, p. 143-192. In E. W. Jones, J. R. Pringle, and J. R. Broach (ed.), The molecular biology of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, vol. II. Gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 38.Schneider, B. L., W. Seufert, B. Steiner, Q. H. Yang, and A. B. Futcher. 1995. Use of polymerase chain reaction epitope tagging for protein tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 11:1265-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwacha, A., and N. Kleckner. 1995. Identification of double Holliday junctions as intermediates in meiotic recombination. Cell 83:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwacha, A., and N. Kleckner. 1997. Interhomolog bias during meiotic recombination: meiotic functions promote a highly differentiated interhomolog-only pathway. Cell 90:1123-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seedorf, M., M. Damelin, J. Kahana, T. Taura, and P. A. Silver. 1999. Interactions between a nuclear transporter and a subset of nuclear pore complex proteins depend on Ran GTPase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:1547-1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shinohara, A., H. Ogawa, and T. Ogawa. 1992. Rad51 protein involved in repair and recombination in S. cerevisiae is a RecA-like protein. Cell 69:457-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sikorski, R. S., and J. D. Boeke. 1991. In vitro mutagenesis and plasmid shuffling: from cloned gene to mutant yeast. Methods Enzymol. 194:302-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun, H., D. Treco, and J. W. Szostak. 1991. Extensive 3′-overhanging, single-stranded DNA associated with the meiosis-specific double-strand breaks at the ARG4 recombination initiation site. Cell 64:1155-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sung, P. 1994. Catalysis of ATP-dependent homologous DNA pairing and strand exchange by yeast RAD51 protein. Science 265:1241-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sym, M., J. Engebrecht, and G. S. Roeder. 1993. ZIP1 is a synaptonemal complex protein required for meiotic chromosome synapsis. Cell 72:365-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanaka, T., T. Nakamura, H. Takagi, and M. Sato. 1997. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel TBP-1 interacting protein (TBPIP): enhancement of TBP-1 action on TAT by TBPIP. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 239:176-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsubouchi, H., and H. Ogawa. 2000. Exo1 roles for repair of DNA double-strand breaks and meiotic crossing over in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:2221-2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tung, K.-S., E. Hong, and G. S. Roeder. 2000. The pachytene checkpoint prevents accumulation and phosphorylation of the meiosis-specific transcription factor Ndt80. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:12187-12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tung, K.-S., and G. S. Roeder. 1998. Meiotic chromosome morphology and behavior in zip1 mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 149:817-832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Voelkel-Meiman, K., and G. S. Roeder. 1990. A chromosome containing HOT1 preferentially receives information during mitotic interchromosomal gene conversion. Genetics 124:561-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wach, A., A. Brachat, R. Pohlmann, and P. Philippsen. 1994. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 10:1793-1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weiner, B. M., and N. Kleckner. 1994. Chromosome pairing via multiple interstitial interactions before and during meiosis in yeast. Cell 77:977-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.West, S. C. 1992. Enzymes and molecular mechanisms of genetic recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 61:603-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu, L., M. Ajimura, R. Padmore, C. Klein, and N. Kleckner. 1995. NDT80, a meiosis-specific gene required for exit from pachytene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:6572-6581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamamoto, A., and Y. Hiraoka. 2001. How do meiotic chromosomes meet their homologous partners? lessons from fission yeast. Bioessays 23:526-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]