Abstract

The DDB2 gene, which is mutated in xeroderma pigmentosum group E, enhances global genomic repair of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and suppresses UV-induced mutagenesis. Because DDB2 transcription increases after DNA damage in a p53-dependent manner, we searched for and found a region in the human DDB2 gene that binds and responds transcriptionally to p53. The corresponding region in the mouse DDB2 gene shared significant sequence identity with the human gene but was deficient for p53 binding and transcriptional activation. Furthermore, when mouse cells were exposed to UV, DDB2 transcription remained unchanged, despite the accumulation of p53 protein. These results demonstrate direct activation of the human DDB2 gene by p53. They also explain an important difference in DNA repair between humans and mice and show how mouse models can be improved to better reflect cancer susceptibility in humans.

The nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway recognizes and removes UV-induced DNA lesions such as 6-4 photoproducts and cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) as well as a broad range of bulky adducts (12). Mutations in NER genes lead to xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), an autosomal recessive disease characterized by hypersensitivity to UV radiation and a severe risk for skin cancer (6).

Some XP patients in complementation group E lack a UV-damaged-DNA binding protein (UV-DDB), which is present in healthy individuals, patients in other XP complementation groups (5), and other patients provisionally assigned to XP group E (XPE) (20). UV-DDB requires the expression of two genes, DDB1 (or p127) and DDB2 (or p48) (8, 17, 31). XPE cells deficient in UV-DDB have inactivating mutations in the DDB2 gene (18, 25). Furthermore, UV-DDB is deficient in rodent cells due to decreased expression of DDB2 (18). XPE and UV-DDB have recently been reviewed (32).

NER consists of two subpathways, transcription-coupled repair and global genomic repair (GGR) (4). Transcription-coupled repair removes lesions from the transcribed strand of DNA, and GGR removes lesions from the genome overall. XPE cells are deficient in GGR (16). Rodent cells are also deficient in GGR of CPDs (4), and expression of DDB2 confers GGR to hamster cells (33).

Accumulation of the tumor suppressor protein p53 after DNA damage activates GGR of CPDs in human cells (11) by a mechanism that has been incompletely understood. UV or ionizing radiation activates the transcription of DDB2 in p53 wild-type cells but not in p53-deficient cells (16). Furthermore, the forced expression of a transfected p53 gene activates DDB2 transcription and increases UV-DDB (16). These data demonstrate that p53 transcriptionally activates the DDB2 gene, but they do not indicate whether this activation is direct or indirect. Here, we report the identification of a p53 response element in the human DDB2 gene and demonstrate binding and direct transcriptional activation of the DDB2 gene by p53. We also show that the mouse DDB2 gene does not contain a functional p53 response element, providing an explanation for the deficiencies of UV-DDB and GGR in mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning the mouse DDB2 cDNA.

A BLASTN search of the mouse expressed sequence tag database was performed with the human DDB2 cDNA sequence. One match was Mus musculus cDNA clone 893619 (GenBank accession no. AA516636) from a Knowles Solter mouse E6 5d whole embryo. When this clone was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.), DNA sequencing revealed internal deletions. To obtain a complete clone, primers for PCR amplification were designed at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the clone. The sequence of the 5′ primer, KnowlesDDB2.84-105F, was 5′-GTAGTCCCTTCCTGTTTTCTCC-3′. The sequence of the 3′ primer, KnowlesDDB2.1567-1683R, was 5′-CCCTGCTCCAACCCTAA-3′. Poly-A+ RNA from NIH 3T3 mouse cells was reverse transcribed by using KnowlesDDB2.1567-1683R and then amplified by PCR with KnowlesDDB2.84-105F and KnowlesDDB2.1567-1683R. The PCR products were cloned into the pCR2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.), and five independent clones yielded the same sequence. The published sequence of a Sugano mouse brain cDNA clone (GenBank accession no. AU035536) contained an additional sequence at the 5′ end of the mouse DDB2 cDNA, which was conserved with the 5′ end of the human DDB2 cDNA. The 5′ end of the mouse cDNA sequence was corrected and extended by 4 nucleotides by sequencing three independent genomic clones from a mouse ES-129/SvJ BAC library (Genome Systems, St. Louis, Mo.). The mouse DDB2 cDNA was subcloned into the pBJ5 vector (28) for expression studies.

Cells.

All cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in 5% CO2. The 041 mut (p53−/−) human fibroblast cell line was a gift from James Ford (Stanford University). The HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cell line, the NMuLi mouse liver cell line, the BNL CL.2 mouse liver cell line, and the WI-38 human lung fibroblast cell line were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Primary wild-type mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) and p53−/− MEF were gifts from Laura Attardi (Stanford University) and used at passage 4.

UV irradiation of cells.

Medium on the cells was removed, and the cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline. The cells were exposed to UVC from a germicidal lamp at a dose of 10 J/m2. Medium was immediately added to the cells after UV exposure.

In vitro translation of p53.

In vitro-translated p53 was synthesized from 1 μg of plasmid DNA containing p53 by using the TNT-coupled rabbit reticulocyte lysate system (Promega, Madison, Wis.). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 90 min after the addition of T3 RNA polymerase. To assess translational efficiency, p53 was labeled with l-[35S]methionine.

DNA oligonucleotides for p53 binding and activation.

Double-stranded oligonucleotides were made by heating and then annealing complementary strands slowly for 2 h. Oligonucleotides for competition electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were resolved by electrophoresis in a nondenaturing Tris-borate-EDTA gel, stained with ethidium bromide, extracted from the appropriate gel slice with 1 M NaCl overnight, purified on a Sep-Pak Vac 1-ml C18 cartridge (Waters Corp., Milford, Mass.), and quantitated with PicoGreen double-stranded DNA quantitation reagent (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) by using a fluorimeter. Double-stranded REhDDB2 was made by annealing 5′-CTAGCAAGCTGGTTGAACAAGCCCTGGGCATGTTTGGCGGGAAGC-3′ and 5′-TCGAGCTTCCCGCCAAACATGCCCAGGGCTTGTTCAACCAGCTTG-3′.The boldface nucleotides in the oligonucleotides indicate the candidate p53 binding sites. Double-stranded REhDDB2mut was made by annealing 5′-CTAGCAAGCTGGTTGAAGAACCCCTGGGGATCTTTGGCGGGAAGC-3′ and 5′-TCGAGCTTCCCGCCAAAGATCCCCAGGGGTTCTTCAACCAGCTTG-3′. Double-stranded REhp21 was made by annealing 5′-CTAGCAAGCTGGTTGAACATGTCCCAACATGTTGGGCGGGAAGC-3′ and 5′-TCGAGCTTCCCGCCCAACATGTTGGGACATGTTCAACCAGCTTG-3′. Double-stranded REhDDB2-L was made by annealing 5′-CTAGCAAGCTGGTTTGAACAAGCCCTGGGCATGTTTGGCGGGAAGTTGGCTTAGCTCC-3′ and 5′-TCGAGGAGCTAAGCCAACTTCCCGCCAAACATGCCCAGGGCTTGTTCAAACCAGCTTG-3′. Double-stranded REmDDB2-L was made by annealing 5′-CTAGCGGGCTAAAAGTAAAGCAGCCCGGAGGAGCGTTTGGCGCGAAGGTGTCTTAGCTGC-3′ and 5′-TCGAGCAGCTAAGACACCTTCGCGCCAAACGCTCCTCCGGGCTGCTTTACTTTTAGCCCG-3′. Double-stranded REhDDB2-I3 was made by annealing 5′-CTAGCGGACAAGGCTTCAGTGAGCTAGGCAAGCCTGGGTGACAGAGCAAGATCC-3′ and 5′-TCGAGGATCTTGCTCTGTCACCCAGGCTTGCCTAGCTCACTGAAGCCTTGTCCG-3′. Double-stranded REhDDB2-I4 was made by annealing 5′-CTAGCAAGCTGGTTAGGCGTGCCTCAGGGCTTGCTTGGCGGGAAGC-3′ and 5′-TCGAGCTTCCCGCCAAGCAAGCCCTGAGGCACGCCTAACCAGCTTG-3′. Double-stranded REhDDB2-3′UTR was made by annealing 5′-CTAGCAGACAAGCCCTCTCTACGCATGTCTC-3′ and 5′-TCGAGAGACATGCGTAGAGAGGGCTTGTCTG-3′. Radiolabeled probes were made by filling in the ends with [α-32P]dCTP with the Klenow fragment of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I. The sequences of the double-stranded oligonucleotides used in competition EMSAs are shown in Fig. 2B. The radiolabeled REhDDB2 probe for the competition EMSAs was made by phosphorylating the 5′ ends with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase.

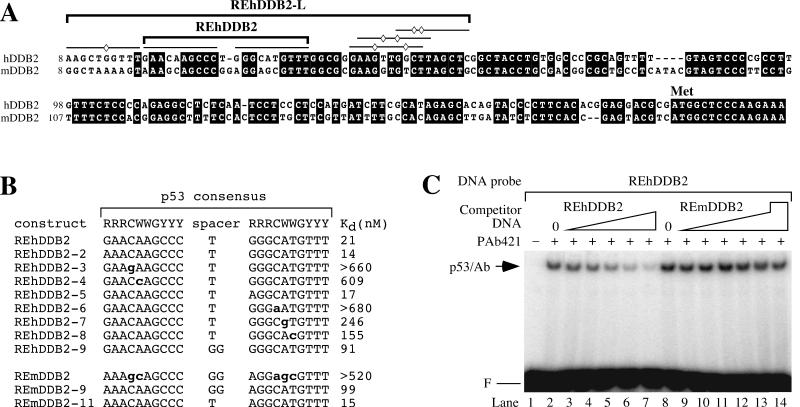

FIG. 2.

The 5′ UTRs in the human and mouse DDB2 genes share high sequence identity and contain several consensus p53 binding sites. (A) Alignment of the human and mouse DDB2 genes. The lines indicate putative p53 binding half sites. The diamonds indicate deviations from the consensus p53 binding site for the human DDB2 gene. The bracketed REhDDB2 was confirmed as a p53 binding site in Fig. 1 (Kd = 21 nM). The bracketed REhDDB2-L is a larger region of the human DDB2 gene confirmed as an even better p53 binding site (Kd = 4 nM). (B) Dissociation constants for p53 binding to different response element constructs. Various DNA constructs derived from the consensus p53 response elements from the human and mouse DDB2 genes were tested for their abilities to compete for binding to in vitro-translated p53 in a competition EMSA such as that shown in panel C. The Kd for REhDDB2 was determined from the fit to equation 2, as described in Materials and Methods. All other dissociation constants were determined from the fit to equation 1. Competition was not observed to any significant degree for REhDDB2-3, REhDDB2-6, or REmDDB2. Therefore, the Kd shown is greater than the highest concentration of cold competitor tested. The boldface lowercase letters indicate deviations from the consensus p53 binding site. R, Y, and W are defined as in the Fig. 1A legend. (C) Competition EMSA for p53 binding. In vitro-translated p53 was incubated with PAb421 and 32P-labeled REhDDB2 DNA probe (0.3 nM) together with unlabeled competitor DNA and resolved by EMSA. Competitor DNA was either REhDDB2 or REmDDB2 at a concentration of 12.5 nM (lanes 3 and 9), 25 nM (lanes 4 and 10), 50 nM (lanes 5 and 11), 100 nM (lanes 6 and 12), or 200 nM (lanes 7 and 13) and was resolved by EMSA. For REmDDB2, a concentration of 520 nM was also tested in lane 14. F and p53/Ab are defined as in the Fig. 1 legend.

EMSAs for DNA binding by p53 and UV-DDB.

For p53 EMSAs, 2.5 μl of in vitro translation extract, 5 μg of HT1080 nuclear extract, or 3 μg of nuclear extract from 041 mut cells transfected with p53 was mixed with 250 ng of PAb421 monoclonal p53 antibody and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Nuclear extracts were prepared as described previously (1). This mixture was then incubated for 30 min at room temperature with 2 μl of 5× binding buffer (100 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 125 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 50% glycerol, 10 mM MgCl2), 0.25 μl of 25 mM dithiothreitol, 0.25 μl of 1% NP-40, 0.25 μl of bovine serum albumin at 4 μg/μl, 250 ng of poly(dI-dC), 245 ng of 32-bp double-stranded f32 DNA (13), and a 32P-labeled DNA probe in a final volume of 10 μl. For competition p53 EMSAs, unlabeled competitor double-stranded DNA ranging from 6.3 to 680 nM was included in the 32P-labeled REhDDB2 probe (0.3 nM) mixture. The reaction mixtures were then resolved by electrophoresis on a 4% Tris-glycine-EDTA polyacrylamide gel and quantified with a phosphorimager. For the UV-DDB EMSAs, 2 μg of whole-cell extract was analyzed as described previously (16).

p53 dissociation constants.

Competition EMSAs were analyzed by plotting binding activity versus concentration of cold competitor DNA. The dissociation constant for the radiolabeled probe (Kd*) is defined as [D*][P]/[D* · P], where D* is the radiolabeled REhDDB2 probe, P is free p53, and D* · P is the radiolabeled probe-p53 complex. The dissociation constant for the cold competitor (Kd) is defined as [D][P]/[D · P], where D is the cold competitor DNA and [D · P] is the cold competitor DNA-p53 complex. The total p53 concentration (PT) is defined as [PT] = [P] + [D* · P] + [D · P]. The binding activity, B, is measured as [D* · P], yielding the equation B = [PT] − [P] − [D · P]. After substituting for [P] and [D · P] by using the dissociation constant equations, we find that B = [PT]/{1 + (Kd*/[D*])(1 + [D]/Kd)}. We define B = Bmax when [D] = 0. Hence, Bmax = [D*][PT]/([D*] + Kd*). Incorporation of Bmax gives

|

(1) |

When the cold competitor DNA is REhDDB2, Kd = Kd* and equation 1 simplifies to

|

(2) |

Kd* for REhDDB2 was determined from the fit to equation 2 and then used in equation 1 to derive Kd values for all elements other than REhDDB2. All fits were performed with KaleidaGraph software (Synergy Software, Reading, Pa.).

p53 and luciferase constructs.

The P72 allele of human p53 was obtained from James Ford. The R72 allele of p53 was made by PCR mutagenesis of P72. Both p53 alleles were subcloned into the pGC-IRES expression vector and verified by DNA sequencing. The mouse p53 cDNA was cloned by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Invitrogen). The mouse p53 cDNA was then subcloned into pGC-IRES. DNA sequence elements tested in luciferase assays were constructed by subcloning into the NheI and XhoI sites of the luciferase reporter vector, pGL3 (Promega).

DNA transfections.

The 041 mut cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 105 cells per 3.6-cm-diameter dish on the day prior to transfection. For the transfection, 1 μg of p53 expression vector (pGC-IRES) and 0.5 μg of luciferase reporter construct were mixed with Lipofectamine Plus reagent and Lipofectamine (Life Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.). Cell extracts were harvested after 24 h with passive lysis buffer (Promega), and scraping was performed with a rubber policeman. Extracts (5 μg) were assessed for luciferase activation by p53 with luciferase assay reagent (Promega).

We attempted to control for transfection efficiency by cotransfecting a Renilla luciferase reporter, pRL-TK (Promega), and utilizing a dual luciferase reporter assay (Promega) but found that this resulted in expression levels that were dependent on p53 transfection. Since this produced biased normalizations for transfection efficiency, we chose not to use this second reporter. Instead, we cotransfected one luciferase reporter with p53 expression vectors in sextuplicate and averaged the data from two to seven independent experiments with different DNA preparations. For EMSAs, 28 μg of p53 was transfected into 041 mut cells (50% confluency) in 150-mm-diameter dishes and harvested after 24 h.

The calcium phosphate transfection kit (Life Technologies, Inc.) was used to transfect 48 μg of DNA into MEF cells (75% confluency) in a 100-mm-diameter dish. Cells were harvested after 48 h.

MEF transductions.

The mouse p53 expression vector or the vector alone was transfected into Phoenix-E packaging cells, and retroviral infections of p53−/− MEF were performed as described previously (7). Cells were harvested for RNA and protein 48 h after infection.

Immunoblot analysis.

To measure p53 protein levels, extracts (15 μg) were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The samples were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with p53 M19 goat polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.) at a dilution of 1/500. To confirm that equivalent amounts of protein extract were present, the blots were stripped and reprobed with hsc70 (K-19) goat polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a dilution of 1/2,000. The secondary antibody was peroxidase-labeled horse anti-goat immunoglobulin G (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) diluted 1/100,000. Supersignal West femto maximum sensitivity substrate (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) was used to develop the blots.

Quantitative PCR.

Cytoplasmic RNA was harvested from cells with an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) along with an RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen) to digest contaminating genomic DNA. RNA was quantitated with a RiboGreen RNA quantitation kit (Molecular Probes). A TaqMan Gold one-step RT-PCR kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) was used to analyze the RNA samples (5 ng). The primers for mouse DDB2 RT-PCRs were 5′-CAGCACCTCACACCCATCAA-3′ and 5′-GGTATCGGCCCACAACAATG-3′. The primers for mouse p21 RT-PCRs were 5′-CCATGTCCAATCCTGGTGATG-3′ and 5′-CGAAGAGACAACGGCACACTT-3′. The primers for mouse DDB1 RT-PCRs were 5′-GGCGAGGCTTCTACCCCTAC-3′ and 5′-GCCCTATCATGCCGTTGACT-3′. The fluorescent probes used in the RT-PCRs were 5′-VIC-CGACCTGGCATTCACGGCACAA-TAMRA-3′ (DDB2), 5′-VIC-CCGACCTGTTCCGCACAGGAGC-TAMRA-3′ (p21), and 5′-VIC-TGCCAAAGAGCACCGAGCCCTG-TAMRA-3′ (DDB1). The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) RT-PCRs were performed with a VIC TaqMan rodent GAPDH control reagents kit (Applied Biosystems). The TaqMan reactions were performed in an ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed with Sequence Detector version 1.7a software (Applied Biosystems). The comparative CT method was used according to user bulletin no. 2 for the ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems).

RESULTS

The 5′ UTR of the human DDB2 gene contains a consensus p53 binding site.

To investigate the transcriptional activation of the DDB2 gene by p53, we searched for consensus p53 binding sites in the human DDB2 gene by using Sequencher (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, Mich.). The consensus p53 binding site consists of two half sites separated by 0 to 13 bp of spacer DNA (9). With the consensus p53 binding half site as the query, we found two half sites separated by a 1-bp spacer in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of DDB2 (Fig. 1A). This putative response element in the human DDB2 gene will be referred to as REhDDB2. As a negative control for experiments in this paper, we constructed REhDDB2mut, which contains four mutations at highly conserved positions of the consensus p53 binding site. As a positive control, we used REhp21, which is the p53 response element from the human p21 gene (10).

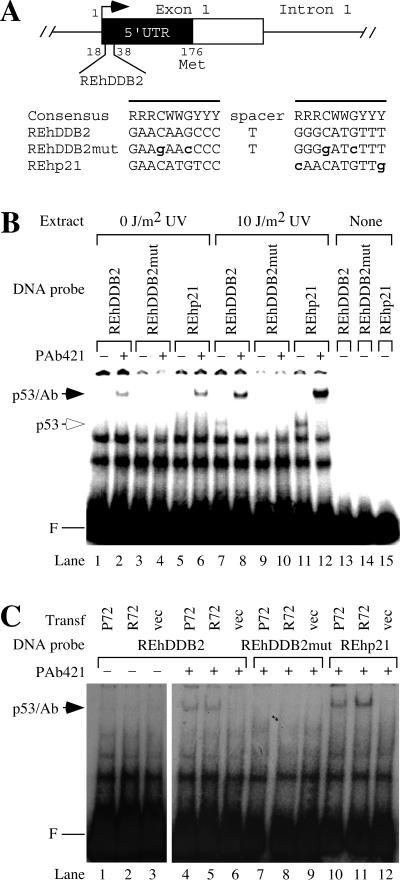

FIG. 1.

The 5′ UTR of the human DDB2 gene contains a consensus sequence for p53 binding. (A) Consensus p53 binding site in the human DDB2 gene. The putative p53 response element from the human DDB2 gene (REhDDB2) is located from 18 to 38 bp downstream of the putative transcriptional start site. The consensus p53 binding site is shown, where R stands for purines A or G, Y stands for pyrimidines C or T, and W stands for A or T. The boldface lowercase letters indicate deviations from the consensus sequence. The lines denote the two half sites for p53 binding. REhDDB2mut was derived from REhDDB2 by mutating four highly conserved sites in the p53 consensus and served as a negative control in the experiments. REhp21 is the p53 response element from the human p21 gene and served as a positive control in the experiments. (B) Binding of p53 in HT1080 cell extracts to REhDDB2. Nuclear extracts were made from HT1080 cells, which had been untreated or treated with UV at a dose of 10 J/m2. A 32P-labeled DNA probe was incubated with the extracts and resolved by EMSA. F marks the position of the free DNA probe. Where indicated, incubations also included the monoclonal antibody PAb421, which binds to p53 and stabilizes its binding activity. The mobilities of the p53-DNA complex and the p53-PAb421-DNA complex are indicated (p53 and p53/Ab, respectively). (C) Binding of p53 in transfected cell extracts to REhDDB2. Nuclear extracts were made from 041 mut (p53−/−) cells, which had been transfected with vector or with one of the common wild-type alleles of p53, P72 or R72. Different 32P-labeled DNA probes were incubated with extracts with or without PAb421 and resolved by EMSA.

p53 binds to the putative response element from the human DDB2 gene.

To test whether p53 can bind to REhDDB2, we prepared a radiolabeled 49-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide containing this sequence. The radiolabeled DNA was incubated with nuclear extracts from human HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells, which have wild-type p53 (27), and the products were resolved by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1B). Binding of p53 to REhDDB2 and REhp21 could be detected in HT1080 extracts only after the cells were exposed to UV radiation. To better detect the presence of p53 binding activity, some incubations also included the monoclonal antibody PAb421, which binds to the C terminus of p53 and enhances its DNA binding activity (15). In the presence of PAb421, supershifted bands were detected for the DNA probes REhDDB2 and REhp21 but not for REhDDB2mut. The supershifted bands were more intense when the HT1080 cells were exposed to UV radiation, which is known to lead to the accumulation of p53 protein (22).

We next transfected p53 into 041 mut (p53−/−) cells, which were derived from Li-Fraumeni fibroblasts (11). The human p53 gene has two common alleles encoding either proline or arginine at codon 72 (P72 or R72, respectively) (23). Because these alleles differed in their abilities to activate the p53 binding site in the p21 gene (34), we tested their ability to activate the p53 binding site in the DDB2 gene. When extracts from the p53-transfected cells were tested for binding activity to REhDDB2, the P72 and R72 alleles of p53 bound equivalently to the REhDDB2 probe DNA (Fig. 1C). Binding activity was specific for the putative p53 response element, since binding also occurred for the REhp21 probe but not for the REhDDB2mut probe. Immunoblots confirmed that extracts from the cells transfected with P72 and R72 contained equivalent amounts of p53 (data not shown).

The 5′ UTR of the homologous mouse DDB2 gene shares significant sequence identity with human DDB2 but is not bound by p53.

To investigate whether the p53 response element from the human DDB2 gene is conserved in mice, we cloned the mouse DDB2 cDNA and compared it to the human DDB2 cDNA. The two cDNAs shared high sequence identity in their open reading frames, as expected, but were also homologous in their 5′ (Fig. 2A) and 3′ UTRs. In particular, the p53 binding site from human DDB2 (REhDDB2) and the corresponding region in mouse DDB2 shared 62% sequence identity. The mouse sequence (REmDDB2) contained five deviations from the consensus p53 binding site (Fig. 2B). We compared REmDDB2 and REhDDB2 for p53 binding by measuring their abilities to compete with a radiolabeled REhDDB2 probe for binding to p53 in the presence of PAb421. Binding to the radiolabeled probe was competed away efficiently by REhDDB2 but not by REmDDB2 (Fig. 2C). The affinity of p53 for REmDDB2 was low, with a dissociation constant (Kd) of >520 nM, in contrast to the high affinity for REhDDB2, with a Kd of 21 nM (Fig. 2B).

To understand the difference in p53 affinity for the mouse and human elements, we systematically mutated the human element to the mouse element. The mutated oligonucleotides were tested in competition EMSAs, and dissociation constants were determined. Any one of the five mouse mutations that led to deviation from the consensus p53 binding site was sufficient to disrupt p53 binding to REhDDB2 (Fig. 2B). Alteration of the spacer also disrupted binding, but to a lesser degree. We also systematically mutated the mouse element to the human element. After testing a large number of altered mouse elements (data not shown), we found that p53 binding was detectable only when all five deviations from consensus were mutated to form REmDDB2-9 (Fig. 2B). Mutating the GG spacer from the REmDDB2-9 to the human T spacer (REmDDB2-11) increased p53 affinity 6.6-fold. Therefore, six mutations in REmDDB2 were necessary to confer p53 binding affinity at the level observed for REhDDB2.

p53 has a high binding affinity for a region in the 5′ UTR of human DDB2.

To search for other consensus p53 binding sites in the human DDB2 gene, we analyzed the human genomic clones RP11-390K5 (GenBank accession no. AC024045), RP11-17G12 (GenBank accession no. AC018410), and 133K12 (GenBank accession no. AC022470). Overlapping contiguous regions from these clones were used to derive the DDB2 genomic structure, including 4.8 kbp upstream of the 5′ UTR and 28.9 kbp downstream of the 3′ UTR. The human DDB2 gene spanned 24.2 kbp, which included 10 exons and 9 introns, consistent with the human DDB2 map of Itoh et al. (19) and the mouse DDB2 map of Zolezzi and Linn (37). Allowing no mismatches and a spacer of 0 to 13 bp yielded only the REhDDB2 element.

A search for consensus p53 binding sites containing one mismatch yielded four additional sites, including a site 8 kb downstream of the 3′ UTR (REhDDB2-3′UTR), a site in intron 4 (REhDDB2-I4), and a site with an adjacent consensus p53 half site in intron 3 (REhDDB2-I3), which will be discussed further in the next section.

The fourth site consisted of a half site with one mismatch adjacent to the upstream consensus half site of REhDDB2. In addition, beginning 6, 7, and 12 bp from the downstream end of REhDDB2, there were three overlapping half sites with two mismatches. The entire region consisting of REhDDB2 and the four adjacent half sites will be referred to as REhDDB2-L (Fig. 2A).

We tested REhDDB2-L for its ability to compete with the labeled REhDDB2 DNA probe. For p53 binding to REhDDB2-L, Kd was 4 nM, representing an affinity fivefold higher than that for REhDDB2 (data not shown). We also tested p53 binding to the corresponding region in the mouse DDB2 gene, designated REmDDB2-L. The ability of REmDDB2-L to compete with the labeled REhDDB2 DNA probe was poor, with a Kd of >330 nM (data not shown).

p53 activates reporters containing REhDDB2 but not reporters containing other candidate p53 binding sites from the human and mouse DDB2 genes.

To determine whether p53 can bind and activate REhDDB2 and REhDDB2-L in vivo, we tested luciferase reporter constructs containing various consensus p53 response elements (Fig. 3). The reporter containing REhDDB2 was activated to a level similar to that observed for activation of the REhp21 reporter when either human or mouse p53 (hp53 or mp53) was cotransfected into 041 mut cells. Consistent with its increased p53 binding activity, the REhDDB2-L reporter was activated four- to sixfold more than the REhDDB2 reporter. There was no difference in activation by the P72 and R72 alleles of p53 (data not shown). In contrast, both mp53 and hp53 failed to activate the REmDDB2 reporter (data not shown) or the REmDDB2-L reporter (Fig. 3). Also, hp53 failed to activate the REhDDB2-I3, REhDDB2-I4, and REhDDB2-3′UTR reporters, the candidate p53 binding sites in the DDB2 gene with one mismatch from the consensus sequence.

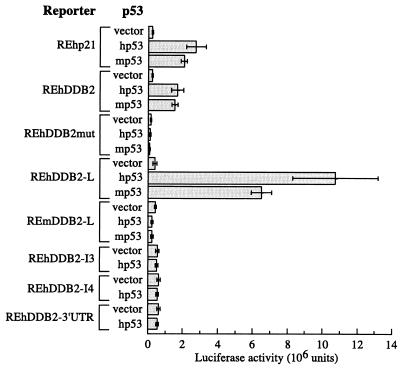

FIG. 3.

p53 activates reporters containing REhDDB2 and REhDDB2-L but not REmDDB2-L, REhDDB2-I3, REhDDB2-I4, or REhDDB2-3′ UTR. Luciferase reporters containing various DNA elements were cotransfected with human p53 (hp53), mouse p53 (mp53), or vector alone into 041 mut (p53−/−) cells. Extracts from the transfections were assessed for luciferase activity. The bars represent means of the results of two to seven independent experiments, each done in sextuplicate.

Transcription of DDB2 in mouse cells is not induced by p53.

Although the REmDDB2-L region in the mouse DDB2 gene was not activated by p53, it remained possible that a cryptic p53 response element was present elsewhere in the gene. To address this possibility, we activated p53 by exposing wild-type MEF and p53−/− MEF to 10 J of UV radiation/m2. Northern blot analysis failed to detect DDB2 mRNA after UV exposure (data not shown), so we used the more sensitive quantitative PCR assay. During the time course after UV exposure, DDB2 and DDB1 mRNA levels remained unchanged in both wild-type and p53−/− MEF, despite the marked increase of p53 in wild-type MEF (Fig. 4A). In contrast, p21 mRNA levels increased dramatically in wild-type MEF after UV exposure, as expected.

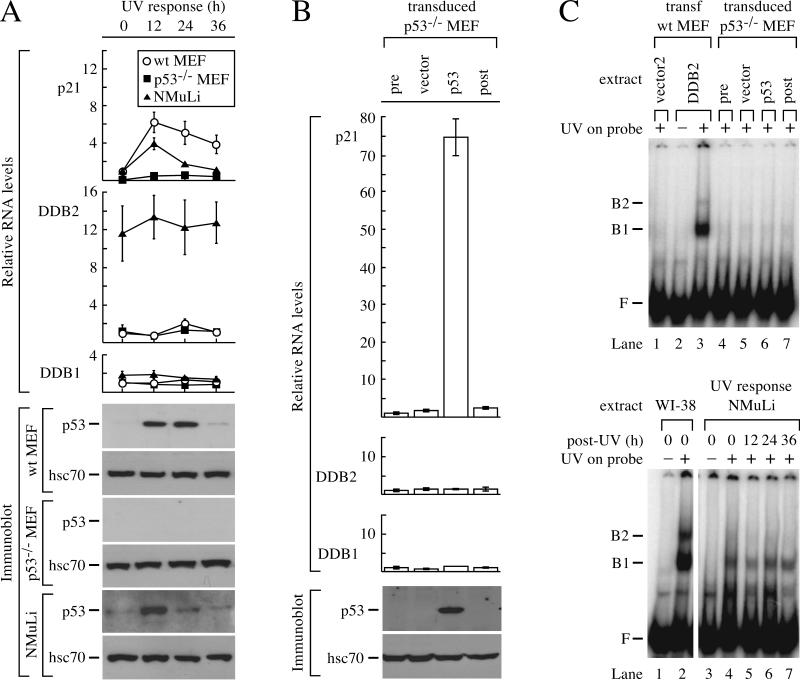

FIG. 4.

Transcription of DDB2 does not respond to p53 in mouse cells. (A) Response of mouse cells to UV. Wild-type MEF, mutant p53−/− MEF, and a normal mouse liver cell line (NMuLi) were exposed to 10 J of UV/m2 and harvested for protein and cytoplasmic RNA after 12, 24, and 36 h. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed for p21, DDB2, and DDB1, and the RNA levels for each gene were normalized to the 0-h time point of wild-type MEF. Immunoblots were performed for p53 and hsc70. (B) Response of p53−/− MEF to transduction of p53. p53−/− MEF were transduced with virus expressing mouse p53 or vector and harvested for protein and cytoplasmic RNA after 48 h. Untransduced cells were also harvested at time points 0 (pre) and 48 (post) h. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed for p21, DDB2, and DDB1, and the RNA levels were normalized to pretransduction levels. Immunoblots were performed for p53 and hsc70. (C) UV-DDB after p53 transduction or UV exposure. Cell extracts were incubated with a 148-bp 32P-labeled DNA probe that was nonirradiated (−) or irradiated with 5,000 J of UV/m2 (+). The upper panel shows an EMSA for UV-DDB in extracts from p53−/− MEF transduced with empty vector (lane 5) or mouse p53 (lane 6). Also included are controls with extracts from untransduced p53−/− MEF at 0 (pre) and 48 (post) h (lanes 4 and 7, respectively) and extracts from wild-type MEF transfected with vector2 (lane 1) or mouse DDB2 (lanes 2 and 3). The lower panel shows an EMSA for UV-DDB in NMuLi extracts 12, 24, and 36 h after UV exposure. Extracts from human wild-type fibroblasts (WI-38; lanes 1 and 2) were included to show the higher levels of UV-DDB in human cells compared to NMuLi. F is defined as in the Fig. 1 legend. wt, wild type; B1 and B2, complexes of UV-damaged DNA bound to UV-DDB.

To determine whether high levels of p53 might be capable of activating DDB2 transcription in mouse cells, we overexpressed p53 in p53−/− MEF by retroviral transduction. Despite the artificially high levels of p53, DDB2 mRNA levels were unaffected (Fig. 4B). In contrast, p21 mRNA was induced over 70-fold after p53 transduction. An EMSA with a labeled, UV-damaged DNA probe showed barely detectable UV-DDB at every point of the UV time course for wild-type and p53−/− MEF (data not shown). Furthermore, UV-DDB remained barely detectable after p53 transduction into p53−/− MEF (Fig. 4C, upper panel). In contrast, transfection of an expression vector for mouse DDB2 conferred UV-DDB to MEF (Fig. 4C, upper panel).

Because the basal level of DDB2 mRNA was low in MEF, it was possible that a tissue-specific repressor or some other transcriptional silencing mechanism might prevent p53-induced DDB2 transcription in these particular mouse cells. To address this issue, we searched for mouse tissues which express higher levels of DDB2 mRNA. Northern blot analysis of various mouse tissues detected higher levels of DDB2 mRNA in liver, testis, thymus, and kidney than in tissues such as skin, brain, lung, muscle, heart, small intestine, spleen, and stomach (data not shown). Therefore, we UV irradiated NMuLi, a cell line derived from the healthy liver of a weanling mouse. The DDB2 mRNA levels in NMuLi cells were more than fivefold higher than those in MEF and were not induced by UV, despite the accumulation of p53 (Fig. 4A). In contrast, p21 mRNA was induced after UV exposure, demonstrating that the accumulated p53 was physiologically active in these cells. UV-DDB levels in NMuLi were readily detectable (Fig. 4C, lower panel) but were not induced after UV exposure. In addition, UV-DDB and DDB2 mRNA were readily detected but not induced in the embryonic mouse liver cell line BNL CL.2 after UV exposure (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The human DDB2 gene is activated by a p53 binding site in the 5′ UTR.

The accumulation of p53 after DNA damage activates transcription of the DDB2 gene (16), which then enhances GGR in human cells (33). However, it was not known whether p53 activates DDB2 transcription directly or indirectly. To address this issue, we searched for a consensus p53 binding site in the DDB2 gene. The search identified a site (REhDDB2) in the 5′ UTR of DDB2 that matched the consensus p53 binding site exactly. REhDDB2 bound to p53 contained in human cell extracts, and this binding activity increased when the extracts were made from UV-irradiated cells. Furthermore, in vitro-translated p53 bound to REhDDB2 with high affinity, and transfection of p53 activated transcription of a luciferase reporter containing REhDDB2. We then identified a putative p53 half site with one mismatch immediately upstream of REhDDB2 and three overlapping putative p53 half sites with two mismatches less than 13 bp downstream of REhDDB2. The affinity of p53 for the region containing REhDDB2 and the four putative p53 half sites (REhDDB2-L) was fivefold higher than that for REhDDB2 alone. Activation of a luciferase reporter containing REhDDB2-L was four- to sixfold greater than that for a reporter containing REhDDB2, consistent with the binding affinities. We tested other candidate p53 response elements in the DDB2 gene with one mismatch from the consensus p53 binding site. None of these response elements was activated by p53. Although we cannot rule out the existence of other p53 response elements in the human DDB2 gene, we have succeeded in identifying REhDDB2-L as a sequence that responds strongly to p53.

The two major alleles of p53 activate DDB2 equivalently.

Beckman et al. studied the distribution of the two major polymorphic alleles of p53 at codon 72, P72 and R72, in different human populations (2). They found that the frequency of the P72 allele increased from 17 to 63% as the geographic location of populations moved from the Arctic Circle to the equator. This raised the possibility that the allele frequencies might be maintained by natural selection related to sun exposure.

We tested the possibility that the P72 allele of p53 might be advantageous where sun exposure is greater because it activates UV-DDB more efficiently for repair. However, P72 and R72 were equally proficient in activating luciferase reporters containing REhDDB2 and REhDDB2-L (data not shown). We also tested several stably integrated REhDDB2 luciferase clones for activation by P72 or R72 transfected at different concentrations but found no differences between the two alleles (data not shown). Furthermore, when p53 from intact cells was tested in EMSAs, we found no difference in binding between the two alleles (Fig. 1C). We conclude that the P72 and R72 alleles of p53 activate DDB2 transcription equivalently. Thus, p53-dependent activation of DDB2 does not appear to explain the changes in p53 allele frequencies with latitude.

Thomas et al. reported that the P72 allele of p53 was more effective than R72 in activating transcription of p21 through their use of a reporter containing the p21 promoter and enhancer region (34). Thus, the P72 allele may induce p21-mediated cell cycle arrest more effectively than the R72 allele. In the setting of equivalent activation of DDB2 and, thus, equivalent levels of GGR, more effective cell cycle arrest should suppress UV-induced mutagenesis and apoptosis (3). This could confer a selective advantage to individuals carrying the P72 allele of p53.

Rodents and humans regulate DDB2 transcription differently.

GGR of CPDs and UV-DDB are greatly decreased in rodent cells compared to human cells (4, 18). The expression of human DDB2 in rodent cells confers GGR of CPDs and UV-DDB (33). GGR deficiency in rodent cells is not due to an absence of the DDB2 gene, since we and others (37) were able to clone the mouse gene. Furthermore, the transfection of mouse DDB2 cDNA into MEF conferred UV-DDB (Fig. 4C, upper panel). Therefore, the low level of GGR in many rodent tissues is due to the low level of DDB2 transcription (Fig. 4A).

The mouse and human DDB2 genes share high sequence identity, including a region in the mouse gene homologous to the p53 response element in the human DDB2 5′ UTR. This homologous region in the mouse DDB2 gene contained several deviations from the human gene and did not respond to p53. To see whether DDB2 transcription could be induced by a cryptic p53 element somewhere else in the mouse DDB2 gene, we exposed wild-type and p53−/− MEF to UV. Transcription of DDB2 remained low and uninducible, despite activation of p53. Furthermore, overexpression of p53 in p53−/− MEF failed to induce DDB2 transcription. Therefore, the lack of a functional p53 response element in the mouse DDB2 gene contributes to the low level of DDB2 transcription in mouse cells.

There may not be any selective pressure to maintain a functional p53 element in the mouse DDB2 gene, since rodents are nocturnal animals with fur to shield them from UV exposure. On the other hand, DDB2 transcription appears to occur at significant levels in some mouse tissues, such as liver, testis, thymus, and kidney, despite the absence of a p53 response element (data not shown). Consistent with DDB2 expression in mouse liver cells, Prost et al. observed significant levels of GGR of CPDs in primary mouse hepatocytes (26). Zolezzi and Linn have also reported DDB activity to be present in mouse plasmacytoma cells (37).

The low levels of DDB2 in MEF and tissues such as skin (data not shown) could be due to a silencing mechanism. This mechanism could have obscured p53-dependent transcriptional activation of DDB2. To rule this out, we tested NMuLi mouse liver cells, which have significant levels of UV-DDB and DDB2 mRNA (Fig. 4A and C, lower panel). In NMuLi cells, UV led to p53 accumulation but failed to induce DDB2 transcription (Fig. 4A). Thus, the mouse DDB2 gene is not regulated by p53, unlike the human DDB2 gene.

Rodent fibroblasts typically show less-efficient GGR than human fibroblasts (21, 24), while mouse hepatocytes have GGR levels that approach those of human fibroblasts (26). Our studies show that these differences in GGR are correlated with differences in DDB2 and UV-DDB expression.

MEF and hepatocytes from p53−/− mice show a loss of GGR (26, 30). Although p53 does not regulate DDB2 in mouse cells, p53 regulates the gadd45 and PCNA genes in human cells and likely in mouse cells, as well (14, 36). Gadd45 and PCNA encode interacting proteins involved in GGR (29). The loss of Gadd45 in MEF causes a reduction in GGR similar to that seen with the loss of p53 (30). Thus, it appears that p53 regulates some GGR genes in mice and humans but regulates DDB2 only in humans.

Although rodent models of human cancer have been widely used, the deficiency of GGR in rodents is a significant limitation. Indeed, some rodent models fail to recapitulate human disease. For example, the Cockayne syndrome B (CSB)-deficient mouse is highly susceptible to skin cancer, unlike CSB humans (35). Loss of CSB leads to the loss of transcription-coupled repair. This occurs in a background of deficient GGR in the mouse and leads to a cancer phenotype that is not seen in humans. A better rodent model for skin cancer can be constructed by engineering the appropriate regulated expression of DDB2.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tom Purcell, who graciously declined to be a coauthor on this paper. He conducted the computer search that first identified REhDDB2, the core p53 binding site described in this paper, and also provided critical comments on the manuscript. We thank James M. Ford for the p53 Pro72 cDNA and 041 mut cells, Gina L. Costa and C. Garrison Fathman for the pGC-IRES expression vector, Laura Attardi for wild-type and p53−/− MEF cells, Garry Nolan for the Phoenix-E packaging cells, Niro Anandasabapathy and Byung Joon Hwang for construction of the p53 Arg72 vector, Kevin Chen for assistance with the MEF transformations, and Niro Anandasabapathy for assistance with the viral transductions. We thank M. Krasnow, R. Lehman, J. Budman, L. DeFazio, O. Hammarsten, U. Lee, K. Rieger, J. Tang, Y. Thorstenson, and V. Tusher for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by a Smith Stanford Graduate Fellowship and NIH CMB training grant GMO7276 to T.T. and a Burroughs-Wellcome Clinical Scientist Award to G.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews, N. C., and D. V. Faller. 1991. A rapid micropreparation technique for extraction of DNA-binding proteins from limiting numbers of mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:2499.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckman, G., R. Birgander, A. Sjalander, N. Saha, P. A. Holmberg, A. Kivela, and L. Beckman. 1994. Is p53 polymorphism maintained by natural selection? Hum. Hered. 44:266-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bissonnette, N., and D. J. Hunting. 1998. p21-induced cycle arrest in G1 protects cells from apoptosis induced by UV-irradiation or RNA polymerase II blockage. Oncogene 16:3461-3469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohr, V., C. Smith, D. Okumoto, and P. Hanawalt. 1985. DNA repair in an active gene: removal of pyrimidine dimers from the DHFR gene of CHO cells is much more efficient than in the genome overall. Cell 40:359-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu, G., and E. Chang. 1988. Xeroderma pigmentosum group E cells lack a nuclear factor that binds to damaged DNA. Science 242:564-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cleaver, J. E., and K. H. Kraemer. 1989. Xeroderma pigmentosum, p. 2949-2971. In C. R. Scriver, A. L. Beaudet, W. S. Sly, and D. Valle (ed.), The metabolic basis of inherited disease, vol. 2. McGraw-Hill, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa, G. L., J. M. Benson, C. M. Seroogy, P. Achacoso, C. G. Fathman, and G. P. Nolan. 2000. Targeting rare populations of murine antigen-specific T lymphocytes by retroviral transduction for potential application in gene therapy for autoimmune disease. J. Immunol. 164:3581-3590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dualan, R., T. Brody, S. Keeney, A. Nichols, A. Admon, and S. Linn. 1995. Chromosomal localization and cDNA cloning of the genes (DDB1 and DDB2) for the p127 and p48 subunits of a human damage-specific DNA binding protein. Genomics 29:62-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Deiry, W. S., S. E. Kern, J. A. Pietenpol, K. W. Kinzler, and B. Vogelstein. 1992. Definition of a consensus binding site for p53. Nat. Genet. 1:45-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Deiry, W. S., T. Tokino, V. E. Velculescu, D. B. Levy, R. Parsons, J. M. Trent, D. Lin, W. E. Mercer, K. W. Kinzler, and B. Vogelstein. 1993. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 75:817-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford, J. M., and P. C. Hanawalt. 1995. Li-Fraumeni syndrome fibroblasts homozygous for p53 mutations are deficient in global DNA repair but exhibit normal transcription-coupled repair and enhanced UV resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:8876-8880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedberg, E. C., G. C. Walker, and W. Siede. 1995. DNA repair and mutagenesis. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 13.Hammarsten, O., L. DeFazio, and G. Chu. 2000. Activation of DNA-dependent protein kinase by single-stranded DNA ends. J. Biol. Chem. 275:1541-1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollander, M. C., I. Alamo, J. Jackman, M. G. Wang, O. W. McBride, and A. J. Fornace. 1993. Analysis of the mammalian gadd45 gene and its response to DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 268:24385-24393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hupp, T. R., D. W. Meek, C. A. Midgley, and D. P. Lane. 1992. Regulation of the specific DNA binding function of p53. Cell 71:875-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hwang, B. J., J. Ford, P. C. Hanawalt, and G. Chu. 1999. Expression of the p48 xeroderma pigmentosum gene is p53-dependent and is involved in global genomic repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:424-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang, B. J., J. Liao, and G. Chu. 1996. Isolation of a cDNA encoding a UV-damaged DNA binding factor defective in xeroderma pigmentosum group E cells. Mutat. Res. 362:105-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang, B. J., S. Toering, U. Francke, and G. Chu. 1998. p48 activates a UV-damaged-DNA binding factor and is defective in xeroderma pigmentosum group E cells that lack binding activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:4391-4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itoh, T., T. Mori, H. Ohkubo, and M. Yamaizumi. 1999. A newly identified patient with clinical xeroderma pigmentosum phenotype has a non-sense mutation in the DDB2 gene and incomplete repair in (6-4) photoproducts. J. Investig. Dermatol. 113:251-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keeney, S., H. Wein, and S. Linn. 1992. Biochemical heterogeneity in xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group E. Mutat. Res. 273:49-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madhani, H., V. Bohr, and P. Hanawalt. 1986. Differential DNA repair in transcriptionally active and inactive proto-oncogenes: c-abl and c-mos. Cell 45:417-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maltzman, W., and L. Czyzyk. 1984. UV irradiation stimulates levels of p53 cellular tumor antigen in nontransformed mouse cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4:1689-1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matlashewski, G. J., S. Tuck, D. Pim, P. Lamb, J. Schneider, and L. V. Crawford. 1987. Primary structure polymorphism at amino acid residue 72 of human p53. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:961-963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mellon, I., G. Spivak, and P. Hanawalt. 1987. Selective removal of transcription-blocking DNA damage from the transcribed strand of the mammalian DHFR gene. Cell 51:241-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nichols, A., P. Ong, and S. Linn. 1996. Mutations specific to the xeroderma pigmentosum group E Ddb-phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 271:24317-24320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prost, S., J. M. Ford, C. Taylor, J. Doig, and D. J. Harrison. 1998. Hepatitis B x protein inhibits p53-dependent DNA repair in primary mouse hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 273:33327-33332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma, S., I. Schwarte-Waldhoff, H. Oberhuber, and R. Schafer. 1993. Functional interaction of wild-type and mutant p53 transfected into human tumor cell lines carrying activated ras genes. Cell Growth Differ. 4:861-869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smider, V., W. K. Rathmell, M. Lieber, and G. Chu. 1994. Restoration of X-ray resistance and V(D)J recombination in mutant cells by Ku cDNA. Science 266:288-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith, M., I.-T. Chen, Q. Zhan, I. Bae, C.-Y. Chen, T. Gilmer, M. Kastan, P. O'Connor, and A. Fornace. 1994. Interaction of the p53-regulated protein gadd45 with proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Science 266:1376-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith, M., J. Ford, M. Hollander, R. Bortnick, S. Amundson, Y. Seo, C. Deng, P. Hanawalt, and A. J. Fornace. 2000. p53-mediated DNA repair responses to UV radiation: studies of mouse cells lacking p53, p21, and/or gadd45 genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:3705-3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takao, M., M. Abramic, M. Moos, V. Otrin, J. Wootton, M. McLenigan, A. Levine, and M. Protic. 1993. A 127 kDa component of a UV-damaged DNA-binding complex, which is defective in some xeroderma pigmentosum group E patients, is homologous to a slime mold protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:4111-4118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang, J., and G. Chu. Xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group E and UV-damaged DNA binding protein. DNA Repair, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Tang, J., B. Hwang, J. Ford, P. Hanawalt, and G. Chu. 2000. Xeroderma pigmentosum p48 gene enhances global genomic repair and suppresses UV-induced mutagenesis. Mol. Cell 5:737-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas, M., A. Kalita, S. Labrecque, D. Pim, L. Banks, and G. Matlashewski. 1999. Two polymorphic variants of wild-type p53 differ biochemically and biologically. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:1092-1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Horst, G. T., H. van Steeg, R. J. Berg, A. J. van Gool, J. de Wit, G. Weeda, H. Morreau, R. B. Beems, C. F. van Kreijl, F. R. de Gruijl, D. Bootsma, and J. H. Hoeijmakers. 1997. Defective transcription-coupled repair in Cockayne syndrome B mice is associated with skin cancer predisposition. Cell 89:425-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yarosh, D. B., L. Alas, J. Kibitel, A. O'Connor, F. Carrier, and A. J. Fornace, Jr. 1993. Cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers in UV-DNA induce release of soluble mediators that activate the human immunodeficiency virus promoter. J. Investig. Dermatol. 100:790-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zolezzi, F., and S. Linn. 2000. Studies of the murine DDB1 and DDB2 genes. Gene 245:151-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]