Abstract

The B-Myb transcription factor has been implicated in coordinating the expression of genes involved in cell cycle regulation. Although it is expressed in a ubiquitous manner, its transcriptional activity is repressed until the G1-S phase of the cell cycle by an unknown mechanism. In this study we used biochemical and cell-based assays to demonstrate that the nuclear receptor corepressors N-CoR and SMRT interact with B-Myb. The significance of these B-Myb-corepressor interactions was confirmed by the finding that B-Myb mutants, which were unable to bind N-CoR, exhibited constitutive transcriptional activity. It has been shown previously that phosphorylation of B-Myb by cdk2/cyclin A enhances its transcriptional activity. We have now determined that phosphorylation by cdk2/cyclin A blocks the interaction between B-Myb and N-CoR and that mutation of the corepressor binding site within B-Myb bypasses the requirement for this phosphorylation event. Cumulatively, these findings suggest that the nuclear corepressors N-CoR and SMRT serve a previously unappreciated role as regulators of B-Myb transcriptional activity.

The transcription factor B-Myb is a member of the family of proteins encoded by the myb proto-oncogenes, which also includes the structurally related proteins A-Myb and c-Myb (26, 29, 31). These three transcription factors, while functionally distinct, have been grouped based on amino acid sequence homology among family members. Unlike A-Myb and c-Myb, the transcriptional activity of B-Myb is constitutively suppressed and appears to be manifest only at specific stages during the cell cycle, during which it is involved in the regulation of a number of genes generally associated with cell proliferation, including cdc2, c-myc, and those encoding DNA polymerase alpha and B-Myb itself (24, 27, 28, 36). More compelling evidence in support of a specific role for B-Myb in proliferation comes from studies which have demonstrated that ablation of B-Myb by antisense oligonucleotides inhibits the growth of human hematopoietic cells and glioblastomas (2, 22), while constitutive expression of B-Myb overrides p53-induced and interleukin-6-induced cell cycle arrest (7, 21). These functional characteristics distinguish B-Myb from c-Myb and A-Myb and suggest that these three Myb proteins have nonredundant functions in gene regulation.

Under most circumstances, B-Myb is unable to activate transcription of its cognate target genes and indeed it may even repress the basal level of transcription of the genes with which it associates (1, 19, 23, 28, 37). However, in proliferating cells it has been observed that as cells progress from the G1 phase to the S phase of the cell cycle, there is an increase in both the expression level and the transcriptional activity of B-Myb. The enhanced expression level can likely be explained by the fact that the B-Myb promoter contains a functional E2F binding site (18). The G1-S phase-restricted manifestation of B-Myb transcriptional activity appears to require the activity of cdk2/cyclin A (1, 19, 28, 37). Direct phosphorylation of B-Myb by cdk2/cyclin A has been demonstrated, though it is not clear how this modification actually enables B-Myb transcriptional activity. It has been suggested that phosphorylation is required in order to overcome an inhibitory function contained within the carboxyl terminus of the receptor, as deletion of this region of the protein enables B-Myb transcriptional activity in the absence of phosphorylation (19, 36). It has not been determined whether the inhibitory activity of the carboxyl terminus of B-Myb is mediated by an autoinhibitory intramolecular interaction or if it requires an intermolecular association with a corepressor protein.

Many transcription factors require an activating event such as ligand binding or phosphorylation to enable them to manifest transcriptional activity. However, B-Myb distinguishes itself from most transcription factors in that its transcriptional activity appears to be actively suppressed. Moreover, in the absence of an activating event this transcription factor may suppress the basal transcription of target genes. Thus, it is not clear if B-Myb activation merely requires it in order to overcome repression or if a second event, subsequent to relief of repression, is required in order to permit it to manifest transcription activity. In looking for insights into this issue, we noticed the similarity between the proposed mechanisms of action of B-Myb and of the nuclear receptor for thyroid hormone (TR). Specifically, it has been shown that TR resides on the promoters of target genes in the absence of the hormone and is able to repress transcription by bringing to target genes the nuclear receptor corepressors N-CoR and SMRT (9, 14). Upon activation by ligand, the corepressors are displaced, coactivators are recruited, and TR-mediated transcriptional activation is permitted. Based on the similarity of the mechanisms of action of TR and B-Myb, we hypothesize that the nuclear receptor corepressors N-CoR and SMRT may be involved in B-Myb action (9, 14). N-CoR and SMRT are homologous corepressors that can associate with the unliganded TR and the retinoic acid receptor, enabling these receptors to repress the basal transcriptional activity of their respective target genes. Within these proteins, specific repression domains that function by recruiting class I and II histone deacetylases (HDACs) to target gene promoters have been mapped (13). When associated with DNA, this complex can deacetylate chromatin and silence transcription. In addition to their ability to interact with nuclear receptors, N-CoR and SMRT have also been shown to interact with and regulate the transcriptional activities of a variety of unrelated transcription factors, including Hox, MyoD, MAD, and SHARP (3, 4, 13, 33). Thus, the influence of these corepressors appears to be more universal than originally anticipated. Consequently, we have investigated whether the corepressors N-CoR and SMRT have roles in regulating the transcriptional activity of B-Myb.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

The expression plasmids of murine B-Myb pcDNA3-B-Myb and pcDNA3-B-Myb1-561 were provided by R. Watson (Imperial College School of Medicine, London, United Kingdom). The plasmid pCMX-N-CoR was from M. G. Rosenfeld (University of California, San Diego). The plasmid pCMX-Gal4-C′SMRT was from J. D. Chen (University of Massachusetts). Plasmids pCMV-cdk2 and pCMV-cdk2DN were from E. Harlow (Massachusetts General Hospital). The plasmid pCMV-cyclinA was from J. R. Nevins (Duke University). The plasmids of pR3SV and pRMb3SV-c-Myb were from T. P. Bender (University of Virginia). Gal4′-C′N-CoR was generated by PCR of a DNA fragment corresponding to N-CoR residues 1944 to 2453 which were then cloned into a PM vector (Clontech). Plasmids Myc-N-CoR and Myc-N-CoR759-2453 were generated by subcloning DNA fragments from pCMX-N-CoR into a pcDNA3-5myc vector. The plasmid for GST fusion of N-CoR ID1 domain (amino acids [aa] 2063 to 2142) was generated by PCR of the corresponding region of N-CoR which were then subcloned into a pGEX-6P-1 vector (Pharmacia). Series of VP16-B-Myb plasmids were made by PCR of the corresponding DNA fragments which were then subcloned into the VP16 vector (Clontech). The reporter plasmid 3A-TK-luc was generated by annealing a pair of 69-mer oligonucleotides containing three copies of Myb binding site A and ligating them into a TK-Luc vector by using HindIII and BamHI sites. The 3A oligonucleotides were as follows: forward, AGCTCTAAAAAACCGTTATAATGTACACTAAAAAACCGTTATAATGTACTCTAAAAAACCGTTATAATG; reverse, GATTTTTTGGCAATATTACATGTGATTTTTTGGCAATATTACATGAGATTTTTTGGCAATATTACCTAG.

GST pull-down assay.

Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins were expressed in bacterial strain BL21 and were isolated by glutathione-conjugated Sepharose 4B beads (Pharmacia). Proteins incorporating [35S]methionine ([35S]Met) were generated by the TNT kit (Promega). GST fusion proteins and beads were incubated with [35S]Met-labeled protein in NETN buffer (20 mM Tris-HCI [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, and 0.5% NP-40) for 16 h at 4°C. Bound proteins were washed twice with NETN buffer and twice with buffer A (2 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40) and were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography.

Cell culture and transfection.

All cultured cells were maintained in minimum essential medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. Culture dishes were precoated with 0.1% gelatin for 10 min at 25°C. Cells were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2. Protocols for transient transfection and luciferase assays were essentially as previously described (8). Briefly, cells were split among 10-mm-diameter culture dishes (for coimmunoprecipitation [co-IP]) and 24-well plates (for luciferase assay) 1 day before the transfection. The lipid-mediated transient transfection was performed with a mixture of Lipofectin (Life Technologies) and plasmid DNA containing 3 μg of DNA for a triplicate of luciferase assay in a 24-well plate (Corning Incorporated) or 18 μg of DNA for a 10-mm-diameter dish (Falcon). Cells were incubated with the Lipofectin-DNA mixture for 3 to 7 h and were then incubated in normal media for an additional 24 to 48 h. For the luciferase assays, luciferase readings were normalized using signals of β-galactosidase (β-Gal) and the final results were shown as means ± standard deviations of triplicate measurements. All data shown are representative of at least three experiments.

Immunoprecipitations and Western blots.

Cultured cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and lysed with buffer T containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 120 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) for 30 min on ice. The whole-cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation and were then precleared by protein A-Sepharose CL-4B (Amersham Biosciences) for 1 h at 4°C. Antibody was then mixed with lysates for 2 h at 25°C or overnight at 4°C. Protein A-Sepharose was added for 2 h and then washed with buffer T for 30 min. Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a Hybond-C nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Biosciences). The membrane was blocked with a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 500 mM NaCl, and 5% nonfat dried milk for 1 h. Primary antibody (1 to 3 μg) was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline plus 0.1% Tween 20 and was incubated with the membrane for 2 h at 25°C or overnight at 4°C. Subsequently the secondary antibodies (diluted 1 to 4,000) were incubated with the membrane for 1 h at 25°C. Anti-B-Myb rabbit polyclonal (N-19), anti-N-CoR goat polyclonal (C-20), anti-myc mouse monoclonal (9E10), anti-myc rabbit polyclonal (A14), and anti TRβ1 (J51) mouse monoclonal antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

RESULTS

B-Myb interacts directly with the nuclear receptor corepressors N-CoR and SMRT.

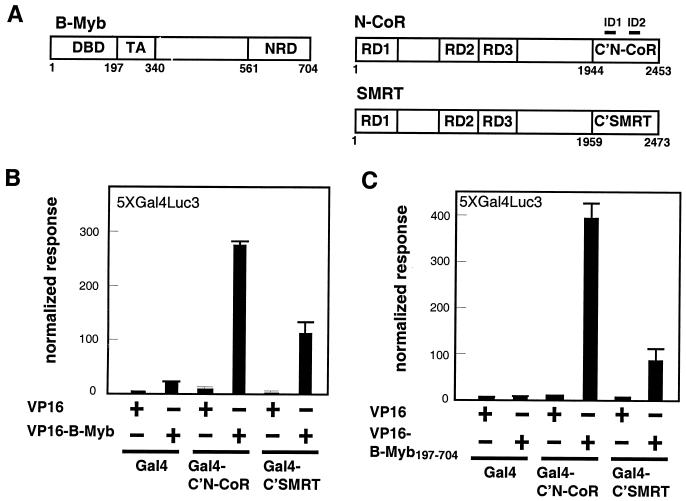

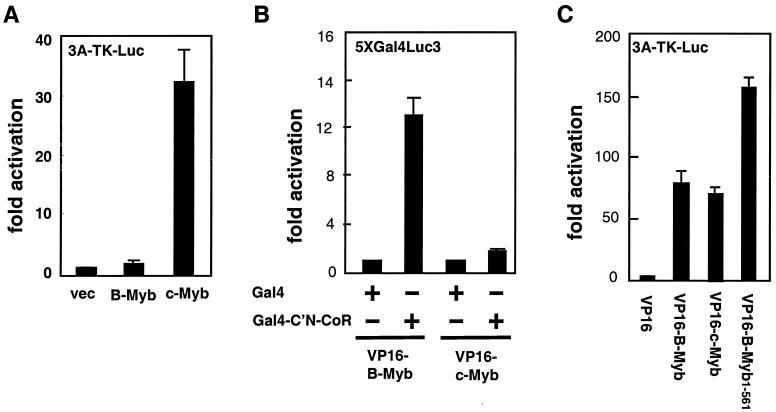

The transcriptional activator B-Myb is maintained in an inactive state in target cells presumably as a consequence of its ability to interact with proteins that function as transcriptional corepressors (26, 29, 31). Based on the general similarity in the proposed mechanism of action of B-Myb and that described for the nuclear hormone receptors, we hypothesized that the corepressors N-CoR and SMRT might be involved in maintaining this transcription factor in a transcriptionally inactive state. Accordingly, we utilized a mammalian two-hybrid assay to examine whether N-CoR (or SMRT) and B-Myb are capable of interacting in intact cells. We first tested the ability of a fusion protein comprising the C terminus of N-CoR (aa 1944 to 2453) fused to the Gal4 DNA binding domain (Gal4-C′N-CoR) to tether a VP16-B-Myb fusion to a Gal4-responsive luciferase reporter. The N-CoR domain chosen does not contain the previously defined repressor domains but rather an intact receptor interaction domain (ID) (11, 14) (Fig. 1A). The results of this initial experiment indicated that Gal4-C′N-CoR is capable of interacting with VP16-B-Myb (Fig. 1B). We noticed that even in the absence of the Gal4-C′N-CoR fusion the VP16-B-Myb protein displayed a significant level of basal transcriptional activity. This may be the result of a nonspecific association between the DNA binding domain of B-Myb and the reporter. To avoid the confounding influence of the observed background activity, we created VP16-B-Myb197-704, a mutant that lacks the previously defined B-Myb DNA binding domain. This mutant protein did not display significant basal transcriptional activity but maintained strong Gal4-C′N-CoR binding activity (Fig. 1C). A similar series of studies led to the observation that SMRT, a corepressor protein homologous to N-CoR, was also capable of interacting with B-Myb. Specifically, it was determined that Gal4-C′SMRT interacts with both VP16-B-Myb and VP16-B-Myb197-704 (Fig. 1B and C). Thus, N-CoR and SMRT, two structurally related corepressors, are capable of interacting with B-Myb within intact cells.

FIG. 1.

B-Myb interacts with C′N-CoR and C′SMRT. (A) Schematic diagrams of N-CoR, SMRT, and B-Myb are adapted from previous reports (15, 31). (B) B-Myb interacts with C′N-CoR and C′SMRT in a mammalian two-hybrid assay. The interaction between GAL4 fusion and VP16 fusion was measured through a mammalian two-hybrid assay on the 5XGal4Luc3 reporter plasmid in CV1 cells. A cytomegalovirus β-galactosidase (CMV-β-Gal) internal control plasmid was used to normalize the luciferase values for transfection efficiency. Means ± standard deviations of triplicates are shown. Results are representative of three independent assays. (C) B-Myb197-704 interacts with C′N-CoR and C′SMRT in the mammalian two-hybrid assay using the same assay conditions as those described for panel B. Results are representative of three independent assays.

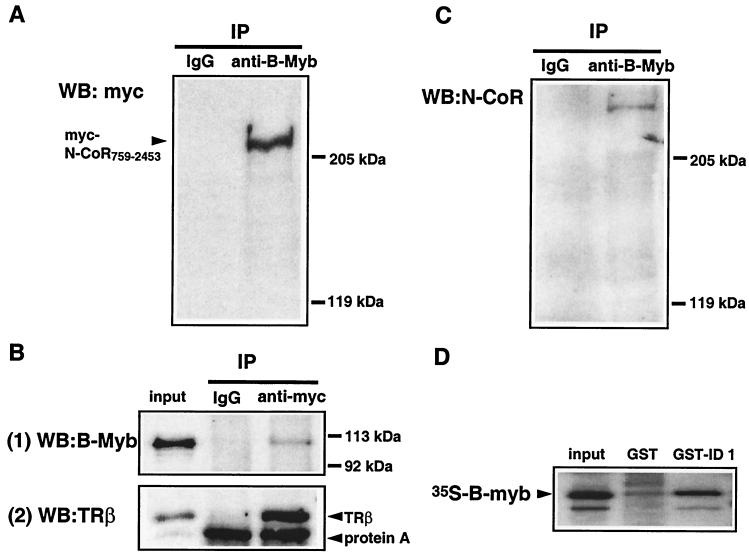

We confirmed that B-Myb and N-CoR can interact by performing co-IP assays on protein extracts from cells transiently transfected with plasmids expressing B-Myb and myc-tagged N-CoR759-2453. In these studies, proteins were immunoprecipitated from extracts with an anti-B-Myb antibody and the presence of N-CoR within the immunoprecipitates was evaluated by Western immunoblotting using an anti-myc antibody. The results indicated that N-CoR759-2453 and B-Myb can form a complex inside cells (Fig. 2A). To further demonstrate that N-CoR and B-Myb interact in cells, we performed the co-IP in the reciprocal manner. In this experiment, myc-N-CoR759-2453 was immunoprecipitated and the level of associated B-Myb was detected by using a Western blot. As shown in Fig. 2B, the results confirm that N-CoR and B-Myb can be coimmunoprecipitated from cells.

FIG. 2.

B-Myb interacts with N-CoR and SMRT in cells. (A) Co-IP between B-Myb and N-CoR759-2453. 293T cells were transfected with pcDNA3-B-Myb and pcDNA3-Myc-N-CoR759-2453 plasmids and were grown for an additional 48 h. Whole-cell lysates (2 mg of total protein) were immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-B-Myb and were then immunoblotted with mouse anti-myc. (B) 293T cells were transfected with pcDNA3-Myc-N-CoR759-2453 plus pcDNA3-B-Myb plasmids (upper panel, labeled 1) or by pcDNA3-Myc-N-CoR759-2453 plus pcDNA3-TRβ1 plasmids (lower panel, labeled 2). Equal molar amounts of pcDNA3-B-Myb and pcDNA2-TRβ1 were used in the transfection, and equal amounts of cell lysates were used in immunoprecipitation. Mouse anti-myc was used for panel 1 and rabbit anti-myc was used for panel 2 for immunoprecipitation. Input, 1%. (C) Co-IP between endogenous B-Myb and N-CoR. Whole-cell lysates of untransfected 293T cells were immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-B-Myb and were then immunoblotted with goat anti-N-CoR. (D) B-Myb interacts with N-CoR domain ID1 (aa 2063 to 2142) in a GST pull-down assay. Two micrograms of GST or GST-ID1 were incubated with 10 μl of TNT lysates containing 35S-labeled B-Myb. Protocols are as described in Materials and Methods. Input, 10%.

The corepressors N-CoR and SMRT were originally identified as proteins that interacted with and suppressed the basal activity of the thyroid and retinoic acid receptors (9, 14). The latter receptors have been shown by most approaches to exhibit robust interactions with SMRT and N-CoR in the absence of an activating ligand. To further characterize the B-Myb-corepressor interactions, we performed a comparative analysis of TR-N-CoR and B-Myb-N-CoR interactions by assessing the level of TRβ or B-Myb that could be immunoprecipitated with myc-tagged N-CoR from cell extracts. Notwithstanding the assumptions inherent in this type of assay, expression levels of the proteins, epitope accessibility, etc., it was clear that TRβ is a more avid N-CoR binder than B-Myb (Fig. 2B). What this actually means, however, is unclear since it has been shown by our group and others that the progesterone and estrogen receptors, two steroid hormone receptors whose pharmacology is modulated dramatically by N-CoR and SMRT, also demonstrate relatively weak corepressor interactions (35). We feel that the functional data (see below) and the observation that the endogenous proteins N-CoR and B-Myb can be coimmunoprecipitated from intact cells indicate that the interaction observed between N-CoR and B-Myb is physiologically relevant (Fig. 2C).

As a final step in evaluating the physical interaction between B-myb and N-CoR, we used in vitro GST pull-down assays to define the region(s) within N-CoR that mediate this interaction (Fig. 2D). Since C′N-CoR interacts with both B-Myb and nuclear receptors such as TR, we considered it possible that the two proteins interact with the same domain within N-CoR. Thus, we examined whether B-Myb can interact with the minimal nuclear receptor IDs of N-CoR. Specifically, the interaction of B-Myb with ID1 (aa 2063 to 2142), an 80-aa domain within C′N-CoR, was assessed, and it was found that this domain was indeed capable of interacting with B-Myb.

N-CoR and SMRT function as repressors of B-Myb transcriptional activity.

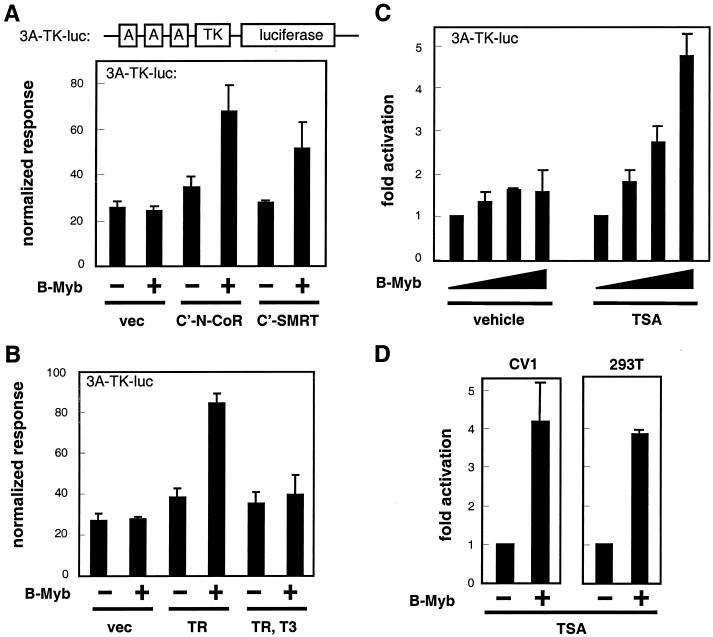

The observation that B-Myb and N-CoR or SMRT interact raised the possibility that these corepressors may negatively regulate B-Myb transcriptional activity. If this were the case, then B-Myb transcriptional activity should be enhanced in cells in which the repression activity of endogenous N-CoR and SMRT is inhibited. To test this idea, we used the following three approaches to inhibit the activities of the two repressors and assessed the effects of these manipulations on B-Myb transcriptional activity: (i) the dominant negative inhibitors C′N-CoR or C′SMRT were expressed, (ii) unliganded TRβ was expressed as a competitive inhibitor of B-Myb-corepressor interactions, and (iii) trichostatin A (TSA) was used to inhibit the HDAC activity associated with N-CoR and SMRT. The transcriptional activity of B-Myb was assessed in transfected CV-1 cells by using a reporter plasmid, 3A-TK-luc, that contains three copies of the Myb binding site A from the mim-1 gene (25) (Fig. 3A). As expected, B-Myb expression alone was not sufficient to activate the 3A-TK-luc reporter. However, coexpression of C′N-CoR or C′SMRT did permit a significant increase in B-Myb transactivation activity (Fig. 3A). A similar result was achieved when we overexpressed TR (TRβ1) to sequester endogenous SMRT and N-CoR (Fig. 3B). It has been shown previously that unliganded TR forms a stable complex with the C terminus of N-CoR and SMRT and that the complex is dissociated when TR interacts with its cognate hormone T3 (9, 14). Not surprisingly, therefore, the ability of TR to enhance the transactivation activity of B-Myb was lost when T3 was added to the transfected cells (Fig. 3B). We believe that the slight enhancement of reporter activity observed in the presence of overexpressed C′N-CoR, C′SMRT, or TRβ1 in the absence of a B-Myb expression plasmid may represent an enhancement of the transcriptional activity of the endogenously expressed B-Myb protein.

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of the repression function of N-CoR and SMRT releases B-Myb transactivation activity. (A) CV1 cells were transfected with 3A-luc reporter, cytomegalovirus β-galactosidase (CMV-β-Gal) internal control vector, and the plasmids pcDNA3-B-Myb, pcDNA3-C′N-CoR, and pCMX-C′SMRT as indicated. Empty pcDNA3 was added to assays to ensure that each assay contained equal amounts of CMV promoters. The result is a representative of three independent assays. (B) CV1 cells were transfected with 3A-TK-luc reporter, CMV-β-Gal internal control vector, and pcDNA3-TRβ. T3, 100 nM. (C) HepG2 cells were transfected with various amounts of pcDNA3-B-Myb. Empty pcDNA3 was added to assays to ensure that each assay contained equal amounts of CMV promoters. TSA, 20 nM. (D) CV1 and 293T cells were transfected with pcDNA3-B-Myb. TSA, 20 nM. Results are representative of three independent assays.

N-CoR and SMRT repress transcriptional activity by recruiting HDACs to target gene promoters (13). If N-CoR and SMRT are bona fide repressors of B-Myb, as we propose, then HDAC inhibitors such as TSA should enhance B-Myb transcriptional activity. Indeed, B-Myb displayed significant transcriptional activity in HepG2 cells treated with TSA (Fig. 3C). A similar enhancement of B-Myb transcriptional activity by TSA was also observed in both CV-1 and 293T cells (Fig. 3D). Cumulatively, these data indicate that B-Myb is repressed by a ubiquitously expressed, TSA-sensitive factor(s). Such characteristics are consistent with those of N-CoR and SMRT, further supporting our hypothesis that N-CoR and SMRT are physiological regulators of B-Myb transcriptional activity.

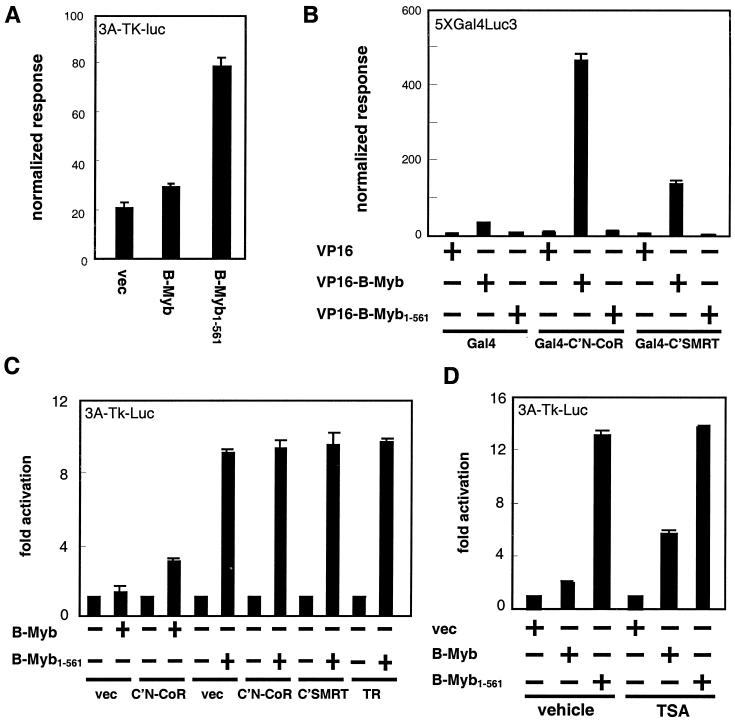

N-CoR and SMRT act through the previously defined negative regulatory domain of B-Myb.

It has been shown by others that truncation of the C terminus of B-Myb releases the constitutively repressed B-Myb transactivation activity (19, 36). Consistent with this, using transiently transfected HepG2 cells, we observed that a B-Myb mutant (B-Myb1-561) that is truncated at the C terminus displays markedly stronger transactivation activity than the full-length B-Myb (Fig. 4A). We next investigated whether the corepressors SMRT and N-CoR can interact with the B-Myb1-561 mutant. Using a mammalian two-hybrid assay, we found that VP16-B-Myb1-704 interacts in a robust manner with Gal4-C′N-CoR and Gal4-C′SMRT while VP16-B-Myb1-561 displays essentially no corepressor binding activity (Fig. 4B). We confirmed that the VP16-B-Myb1-561 fusion protein was properly expressed by demonstrating that it was able to activate transcription of the Myb-responsive 3A-TK-luc reporter (Fig. 6C). Thus, a correlation was established between enhancement of B-Myb1-561 transcriptional activity and loss of N-CoR and SMRT binding activity. This correlation was further demonstrated by the observation that unlike that of full-length B-Myb (Fig. 2), the transcriptional activity of B-Myb1-561 cannot be enhanced by C′N-CoR, C′SMRT, unliganded TRβ, or TSA (Fig. 4C and D).

FIG. 4.

C-terminal truncation of B-Myb loses N-CoR binding activity. (A) HepG2 cells were transfected with 3A-TK-luc, cytomegalovirus β-galactosidase (CMV-β-Gal), and the plasmids as indicated. Each assay contains equal amounts of CMV promoters. (B) HepG2 cells were transfected with 5XGal4Luc3, CMV-β-Gal, and the plasmids as indicated. The results for the mammalian two-hybrid assays are representative of three independent experiments. (C) HepG2 cells were transfected with 3A-TK-luc, CMV-β-Gal, and the plasmids as indicated. (D) HepG2 cells were transfected with 5XGal4Luc3, CMV-β-Gal, and the plasmids as indicated. TSA (20 nM; vehicle, ethanol) was added 24 h after transfection, and cells were grown for additional 24 h.

FIG. 6.

C-Myb does not associate with N-CoR. (A) HepG2 cells were transfected with 3A-TK-luc, cytomegalovirus β-galactosidase (CMV-β-Gal), and the plasmids as indicated. The plasmid for B-Myb is pcDNA3-B-Myb, and its control vector is pcDNA3. The plasmid for c-Myb is pRMb3SV/c-Myb, and its control vector is pR3SV. Each assay contains equal amounts of CMV promoters. (B) HepG2 cells were transfected with 5XGal4Luc3, CMV-β-Gal, and the plasmids as indicated. The results for the mammalian two-hybrid assays are representative of three independent experiments. (C) HepG2 cells were transfected with 3A-TK-luc, CMV-β-Gal, and the plasmids as indicated.

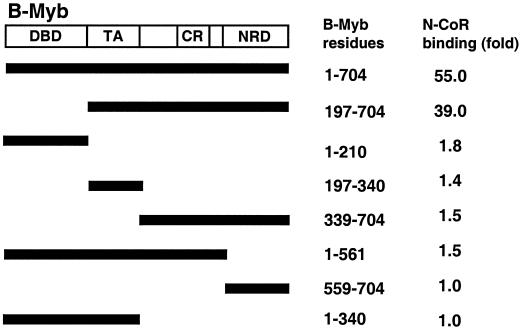

Clearly, the repressor activity of B-Myb requires the C terminus of the protein, which prompted us to test whether this domain is sufficient for N-CoR interaction. To address this issue, we constructed a series of B-Myb mutants and measured their abilities to interact with N-CoR using a mammalian two-hybrid assay (Fig. 5). The result of this analysis suggests that the minimal requirement for N-CoR binding is B-Myb197-704, which includes the transactivation domain (TA), the conserved region (CR), and the negative regulatory domain (NRD). Within B-Myb197-704, neither TA, CR, nor NRD showed significant N-CoR binding activity. These data indicate that although truncation of the NRD abolishes N-CoR binding, NRD itself does not comprise the corepressor binding domain. Instead, a much larger region of B-Myb (aa 197 to 704) is necessary to maintain the interaction between N-CoR and B-Myb.

FIG. 5.

Several B-Myb domains are required for B-Myb/N-CoR interaction. The domain structure of B-Myb was adapted from findings by Saville and Watson (31). B-Myb DNA binding domain (DBD), transactivation domain (TA), conserved region (CR), and negative regulatory domain (NRD) encompass residues 1 to 210, 197 to 340, 470 to 550, and 561 to 704, respectively. Individual domains, combinations of domains, and complementary regions of such domain(s) were generated as VP16 fusion. Their N-CoR binding activities were measured by their ability to associate with Gal4-C′N-CoR in the mammalian two-hybrid assay in CV1 cells. N-CoR binding (fold) was the fold activation in the two-hybrid assay.

C-Myb does not associate with N-CoR.

In addition to B-Myb, the myb family of transcription factors has two other members, A-Myb and c-Myb (26, 29, 31). However, the region whose high degree of amino acid homology has been used to group A-, B-, and c-Myb in the same family (the DNA binding domain) does not overlap with the carboxyl-terminal N-CoR interacting domain mapped in B-Myb. In addition, unlike B-Myb, c-Myb is a constitutive transcriptional regulator and thus may not be subject to regulation by a corepressor (26, 29, 31). Regardless, we felt that it was important to determine if N-CoR and SMRT were able to interact with other myb family members. Specifically, we evaluated potential interactions between N-CoR and c-Myb. Using the 3A-TK-luc reporter, we were able to show that in HepG2 cells c-Myb displays significant transcriptional activity whereas B-Myb activity is completely repressed under the same conditions (Fig. 6A). We further demonstrated by a two-hybrid assay that VP16-c-Myb does not interact with Gal4-C′N-CoR while VP16-B-Myb does (Fig. 6B). Our control experiments (Fig. 6C) indicated that both VP16-B-Myb and VP16-c-Myb are capable of activating the Myb-responsive 3A-TK-luc reporter, suggesting that the VP16-c-Myb fusion protein was properly expressed. Therefore, our data suggest that c-Myb does not possess intrinsic N-CoR binding activity.

Cdk2/cyclin A-mediated phosphorylation blocks the ability of B-Myb to interact with corepressors.

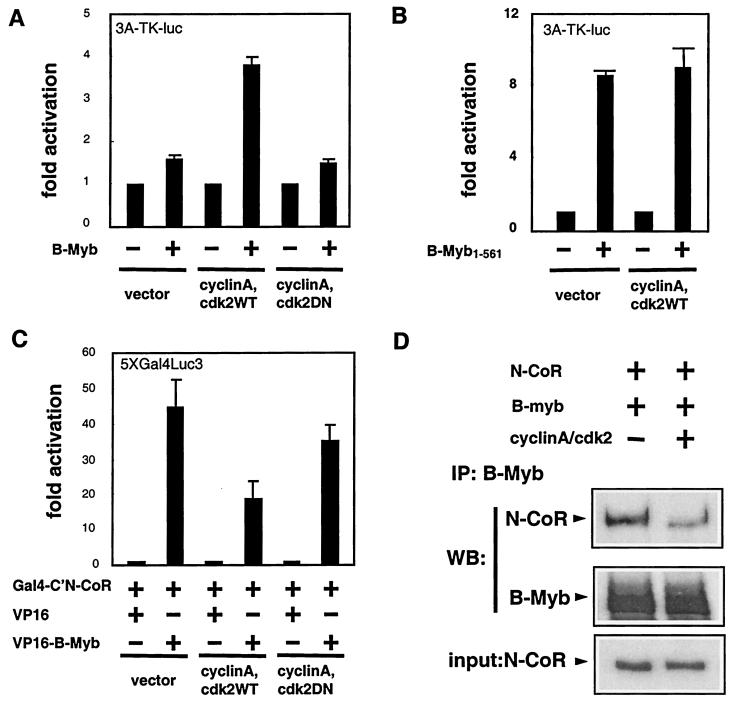

It has been shown previously that phosphorylation of B-Myb by cdk2/cyclin A enhances its transcriptional activity in U-2OS, SAOS-2, and QT6 cells (1, 19, 28, 37). Consistent with these observations, we found that in HepG2 cells expression of cdk2/cyclin A markedly enhances B-Myb's ability to transactivate the 3A-TK-luc reporter (Fig. 7A). A dominant negative form of cdk2, cdk2DN, that lacks kinase activity has been developed (34). When this protein was expressed with cyclin A in HepG2 cells, it had no effect on B-Myb transcriptional activity (Fig. 7A). The transcriptional activity of B-Myb1-561, unlike that of B-Myb, was not affected by cyclinA/cdk2 (Fig. 7B). In fact, the insensitivity of B-Myb upon cyclin A treatment has also been observed by others (6). Since we have shown that B-Myb, but not B-Myb1-561, interacts with corepressors N-CoR and SMRT, we hypothesized that cdk2/cyclin A-mediated phosphorylation could affect the interaction between B-Myb and the negative regulatory factors N-CoR and SMRT.

FIG. 7.

Cyclin A/cdk2 destabilizes N-CoR-B-Myb interaction. (A) Cyclin A/cdk2 releases B-Myb transactivation activity. HepG2 cells were transfected with 3A-TK-luc, cytomegalovirus β-galactosidase (CMV-β-Gal), pcDNA3-B-Myb, and plasmids as indicated. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Effects of cyclin A/cdk2 on the transactivation activity of B-Myb1-561. HepG2 cells were transfected with 3A-TK-luc, CMV-β-Gal, pcDNA3-B-Myb, and plasmids as indicated. (C) CV1 cells were transfected with 5XGal4Luc3, CMV-β-Gal, and plasmids as indicated. Results for the mammalian two-hybrid assay are representative of three independent assays. (D) 293T cells were transfected with the plasmids indicated and incubated at 37°C for 40 h. The whole-cell extract was generated for immunoprecipitation with rabbit anti-B-Myb antibody. Mouse anti-myc was used in Western blotting to detect myc-N-CoR759-2453. Rabbit anti-B-Myb was used to confirm the precipitated B-Myb.

Using a mammalian two-hybrid assay, we found that the interaction between B-Myb and N-CoR is reduced in the presence of overexpressed cdk2/cyclin A (Fig. 7C). No significant reduction in the interaction between B-Myb and N-CoR was observed when the two-hybrid assay was performed in the presence of overexpressed cdk2DN. The role of cdk2/cyclin A as a modulator of B-Myb-corepressor interactions was confirmed by using a co-IP assay (Fig. 7D). Specifically, we measured the amount of myc-tagged N-CoR759-2453 that was associated with the B-Myb complex in extracts of transfected cells in the presence or absence of overexpressed cdk2/cyclin A. We found that coexpression of cdk2/cyclin A correlates with significantly reduced ability of B-Myb to associate with N-CoR under conditions where N-CoR and B-Myb expression levels were not affected (Fig. 7D). It appears, therefore, that cdk2/cyclin A is a key regulator of the transcriptional activity of B-Myb and that it functions by regulating the ability of the transcription factor to interact with the corepressors N-CoR and SMRT.

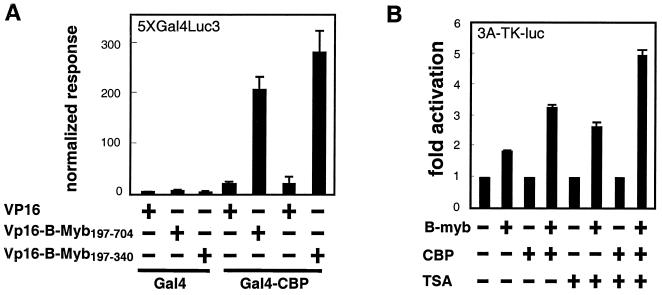

CBP interacts with and potentiates B-Myb transcriptional activity.

Thus far, our studies have indicated that inhibition of the activity of corepressors N-CoR and SMRT is a key step in the activation of B-Myb. However, the identities of the positive acting factors which interact with the derepressed B-Myb proteins and permit it to activate transcription have not been well characterized. Recently, it has been shown that CBP, a general coactivator protein, can interact with B-Myb (6). We have been able to confirm this finding in our model systems using a co-IP assay to demonstrate that CBP is capable of associating with B-Myb (not shown). These interactions were confirmed in a two-hybrid assay which indicated that B-Myb, specifically a domain spanning residues 197 to 340, was able to interact with CBP (Fig. 8A). This particular region of B-Myb (aa 197 to 340) has previously been shown to constitute the TA of this coactivator. In light of these findings, we considered that it might be possible to increase the dynamic range of B-Myb transactivation by inhibiting the corepressor function of N-CoR and SMRT, thus facilitating the coactivator function of CBP. Consequently, we investigated whether CBP and N-CoR (or SMRT) cooperate in the regulation of B-Myb transactivation activity. The results of our transcription assay suggested that coexpression of CBP stimulates B-Myb transactivation activity (Fig. 8B). When the HDAC inhibitor TSA is added, the activity of B-Myb is enhanced, and further potentiation of B-Myb activity is achieved when both TSA and CBP are present. It appears, therefore, that the activity of B-Myb in target cells may be subject to (i) positive regulation by coactivators such as CBP and (ii) negative regulation by corepressors such as N-CoR (or SMRT).

FIG. 8.

CBP interacts with B-Myb and potentiates B-Myb transcriptional activity. (A) CBP interacts with B-Myb197-704 and B-Myb197-340 in a mammalian two-hybrid assay. CV1 cells were transfected with 5XGal4Luc3, cytomegalovirus β-galactosidase (CMV-β-Gal), and the plasmids as indicated. (B) Effects of CBP and TSA on a B-Myb transcription assay. 293T cells were transfected with 3A-TK-luc, CMV-β-Gal, and plasmids as indicated. TSA concentration, 20 nM. Results are representative of three independent assays.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have used several experimental approaches to demonstrate that N-CoR and/or SMRT directly interacts with B-Myb and regulates its transcriptional activity. Under most circumstances, B-Myb is maintained in an inhibited state in cells. We were able to relieve this repression and enable B-Myb transcriptional activity by inhibiting the activity of the corepressors using either dominant negative corepressor mutants or pharmacological inhibitors. B-Myb transcriptional activity was also manifest when mutants were introduced into the protein that blocks B-Myb's ability to interact with N-CoR and SMRT. It has been proposed by others that direct phosphorylation of B-Myb by cdk2/cyclin A is the physiologically relevant signaling event that leads to its conversion from an inactive to a transcriptionally active state. Our findings support this hypothesis and demonstrate that phosphorylation decreases the ability of B-Myb to interact with N-CoR. Considering the fact that B-Myb, N-CoR, and SMRT are widely expressed in almost all cells (9, 14, 31) and our observation that endogenous B-Myb and N-CoR can interact, it is likely that the corepressors can function as physiological regulators of B-Myb transcriptional activity.

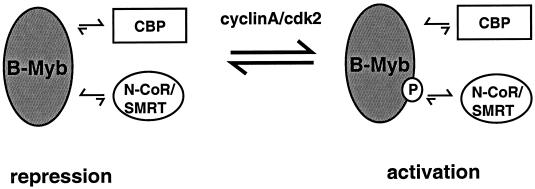

Based on our findings and those of others, we propose a simple model to explain how B-Myb transcriptional activity is regulated by the corepressors N-CoR and SMRT and by the coactivator CBP (Fig. 9). Specifically, we suggest that under most circumstances B-Myb activity is suppressed as a consequence of its ability to interact with N-CoR or SMRT. However, during the S phase of the cell cycle two distinct events can occur. First, there is an increase in B-Myb expression that may enable a titration of the available corepressors and decrease the threshold for activation. Secondly, at the S phase of the cell cycle the cdk2/cyclin A pair can phosphorylate B-Myb, an event that leads to the disruption of the interaction between B-Myb and the corepressors. When the negative influence of the corepressor is removed, CBP is able to interact with the transactivation domain of B-Myb and its positive transcriptional activity is manifest. This model would suggest that alterations in the integrity, expression level, or activity of N-CoR or SMRT would have a profound effect on B-Myb transcriptional activity. We believe that these studies provide compelling evidence that N-CoR and/or SMRT is a physiologically relevant negative regulator of B-Myb transcriptional activity, an association that suggests that these corepressors may be involved in cell cycle regulation.

FIG. 9.

Schematic model illustrating how N-CoR and SMRT cooperate with CBP in regulating B-Myb transcriptional activity.

Studies from others have revealed that there are multiple sites in B-Myb that can be phosphorylated by cdk2/cyclin A (5, 17, 32). Many of these sites are likely to be involved in regulating the interaction of B-Myb with N-CoR and SMRT since mutation of each leads to a progressive increase in the transcriptional activity of this coactivator. A mutation of up to four of the major cdk2/cyclin A phosphorylation sites reduces, but does not totally inhibit, cyclin/cdk2's ability to enhance the transcriptional activity of B-Myb (32). This indicates that there may be additional sites on B-Myb (or in other proteins interacting with B-Myb) where phosphorylation by cdk2/cyclin A is involved in regulating the interaction of this transcription factor with N-CoR. In line with this apparent complexity, we have shown that the N-CoR binding domain on B-Myb is large, comprising most of the carboxyl half of the protein. Although all indications are that B-Myb is the primary target of cdk2/cyclin A phosphorylation in this B-Myb-N-CoR regulatory system, we cannot rule out the possibility that N-CoR may also be subject to cdk2/cyclin A-mediated phosphorylation.

In this study we have found that the transcriptional coactivator CBP interacts directly with the previously defined transactivation domain within B-Myb. We do not know whether the coactivator and the corepressor bind to B-Myb simultaneously or whether displacement of the coactivator is required for subsequent coactivator recruitment. Until recently, the sequential model was favored. However, there is an increasing amount of evidence that suggests that transcriptional repression and activation may be more closely regulated than was previously thought. This position is supported by the recent demonstration that the nuclear receptor cofactor SHARP can interact with both the coactivator SRA and the SMRT/HDAC corepressor complex (33). In another study, p300 (a coactivator) and Groucho (a corepressor) were demonstrated to bind separate domains of the transcription factor NK-4 (10). Of more direct relevance to our studies, however, was the demonstration that the homeobox protein heterodimer Hox-pbx, N-CoR, and CBP exist in a single complex and that PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Hox-pbx by PKA permits this transcription factor to activate target gene transcription (3, 30). Interestingly, PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Hox-pbx enhances its ability to interact with CBP. Whether phosphorylation has any effect on the interaction of corepressors with this transcription factor pair is not known. However, it appears that the regulation of B-Myb transcriptional activity occurs in a manner that is similar to that of other well-characterized transcription factors. Interestingly, we found in a previous study that addition of 8-Br-cAMP, a PKA activator, to cells was sufficient to abolish the interaction between the N-CoR and the human progesterone receptor (35). Thus, phosphorylation may be a general way of displacing N-CoR and SMRT from transcription factors.

In addition to B-Myb, N-CoR and SMRT have been shown to interact with numerous other transcription factors (3, 4, 13, 33). Thus, although originally classified as regulators of the transcriptional activity of nuclear receptors, they are clearly involved in a more diverse array of cellular processes. N-CoR and SMRT are not abundant proteins, and therefore it is likely that alterations in the expression levels or activities of these corepressors would impact several different processes. With respect to the corepressors themselves, it has been shown that genetic disruption of the corepressor N-CoR in mice gives a complicated embryonic lethal phenotype (16). This suggests that N-CoR and SMRT are not able to substitute for each other in all circumstances. In breast tumors that are resistant to the antiestrogen tamoxifen, a previous study has demonstrated that the corepressors are significantly down-regulated (20). Whereas these studies conclude that corepressor down-regulation permits tamoxifen to manifest agonist activity and that this explains tumor progression, it is equally likely that derepression of B-Myb or other transcription factors may also be involved. Given that N-CoR and SMRT interact with different transcription factors in cells, it is possible that a pathological overexpression of any one of these partners could titrate out the available corepressors and enhance the activity of multiple, functionally unrelated, transcription factors. In support of this hypothesis, we demonstrated that overexpression of apo-TR leads to an enhancement of B-Myb transcriptional activity. A mechanism such as this may help to understand the puzzling observation that overexpression of B-Myb can activate the HSP70 promoter despite the fact that a B-Myb binding site in this promoter has not yet been identified (12).

Acknowledgments

We thank Roger J. Watson for the B-Myb expression plasmids pcDNA3-B-Myb and pcDNA3-B-Myb1-561, Ed Harlow for pCMV-cdk2 and pCMV-cdk2DN, and Timothy P. Bender for pR3SV and pRMb3SV-c-Myb. We thank Anthony R. Means and Tso-Pang Yao for helpful insight and suggestions.

This work was supported by a U.S. Army breast cancer research grant to X.L. (DAMD17-00-1-0234) and an NIH grant to D.P.M. (DK50494).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ansieau, S., E. Kowenz-Leutz, R. Dechend, and A. Leutz. 1997. B-Myb, a repressed trans-activating protein. J. Mol. Med. 75:815-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arsura, M., M. Introna, F. Passerini, A. Mantovani, and J. Golay. 1992. B-myb antisense oligonucleotides inhibit proliferation of human hematopoietic cell lines. Blood 79:2708-2716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asahara, H., S. Dutta, H. Y. Kao, R. M. Evans, and M. Montminy. 1999. Pbx-Hox heterodimers recruit coactivator-corepressor complexes in an isoform-specific manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:8219-8225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey, P., M. Downes, P. Lau, J. Harris, S. L. Chen, Y. Hamamori, V. Sartorelli, and G. E. Muscat. 1999. The nuclear receptor corepressor N-CoR regulates differentiation: N-CoR directly interacts with MyoD. Mol. Endocrinol. 13:1155-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartsch, O., S. Horstmann, K. Toprak, K. H. Klempnauer, and S. Ferrari. 1999. Identification of cyclin A/Cdk2 phosphorylation sites in B-Myb. Eur. J. Biochem. 260:384-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bessa, M., M. K. Saville, and R. J. Watson. 2001. Inhibition of cyclin A/Cdk2 phosphorylation impairs B-Myb transactivation function without affecting interactions with DNA or the CBP coactivator. Oncogene 20:3376-3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bies, J., B. Hoffman, A. Amanullah, T. Giese, and L. Wolff. 1996. B-Myb prevents growth arrest associated with terminal differentiation of monocytic cells. Oncogene 12:355-363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang, C., J. D. Norris, H. Gron, L. A. Paige, P. T. Hamilton, D. J. Kenan, D. Fowlkes, and D. P. McDonnell. 1999. Dissection of the LXXLL nuclear receptor-coactivator interaction motif using combinatorial peptide libraries: discovery of peptide antagonists of estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:8226-8239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, J. D., and R. M. Evans. 1995. A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature 377:454-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi, C. Y., Y. M. Lee, Y. H. Kim, T. Park, B. H. Jeon, R. A. Schulz, and Y. Kim. 1999. The homeodomain transcription factor NK-4 acts as either a transcriptional activator or repressor and interacts with the p300 coactivator and the Groucho corepressor. J. Biol. Chem. 274:31543-31552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen, R. N., F. E. Wondisford, and A. N. Hollenberg. 1998. Two separate NCoR (nuclear receptor corepressor) interaction domains mediate corepressor action on thyroid hormone response elements. Mol. Endocrinol. 12:1567-1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foos, G., S. Natour, and K. H. Klempnauer. 1993. TATA-box dependent trans-activation of the human HSP70 promoter by Myb proteins. Oncogene 8:1775-1782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinzel, T., R. M. Lavinsky, T. M. Mullen, M. Soderstrom, C. D. Laherty, J. Torchia, W. M. Yang, G. Brard, S. D. Ngo, J. R. Davie, E. Seto, R. N. Eisenman, D. W. Rose, C. K. Glass, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 1997. A complex containing N-CoR, mSin3 and histone deacetylase mediates transcriptional repression. Nature 387:43-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horlein, A. J., A. M. Naar, T. Heinzel, J. Torchia, B. Gloss, R. Kurokawa, A. Ryan, Y. Kamei, M. Soderstrom, C. K. Glass, et al. 1995. Ligand-independent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor co-repressor. Nature 377:397-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu, X., and M. A. Lazar. 2000. Transcriptional repression by nuclear hormone receptors. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 11:6-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jepsen, K., O. Hermanson, T. M. Onami, A. S. Gleiberman, V. Lunyak, R. J. McEvilly, R. Kurokawa, V. Kumar, F. Liu, E. Seto, S. M. Hedrick, G. Mandel, C. K. Glass, D. W. Rose, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 2000. Combinatorial roles of the nuclear receptor corepressor in transcription and development. Cell 102:753-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson, T. K., R. E. Schweppe, J. Septer, and R. E. Lewis. 1999. Phosphorylation of B-Myb regulates its transactivation potential and DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 274:36741-36749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam, E. W., and R. J. Watson. 1993. An E2F-binding site mediates cell-cycle regulated repression of mouse B-myb transcription. EMBO J. 12:2705-2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane, S., P. Farlie, and R. Watson. 1997. B-Myb function can be markedly enhanced by cyclin A-dependent kinase and protein truncation. Oncogene 14:2445-2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lavinsky, R. M., K. Jepsen, T. Heinzel, J. Torchia, T. M. Mullen, R. Schiff, A. L. Del-Rio, M. Ricote, S. Ngo, J. Gemsch, S. G. Hilsenbeck, C. K. Osborne, C. K. Glass, M. G. Rosenfeld, and D. W. Rose. 1998. Diverse signaling pathways modulate nuclear receptor recruitment of N-CoR and SMRT complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:2920-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin, D., M. Fiscella, P. M. O'Connor, J. Jackman, M. Chen, L. L. Luo, A. Sala, S. Travali, E. Appella, and W. E. Mercer. 1994. Constitutive expression of B-myb can bypass p53-induced Waf1/Cip1-mediated G1 arrest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:10079-10083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin, D., M. T. Shields, S. J. Ullrich, E. Appella, and W. E. Mercer. 1992. Growth arrest induced by wild-type p53 protein blocks cells prior to or near the restriction point in late G1 phase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:9210-9214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marhamati, D. J., and G. E. Sonenshein. 1996. B-Myb expression in vascular smooth muscle cells occurs in a cell cycle-dependent fashion and down-regulates promoter activity of type I collagen genes. J. Biol. Chem. 271:3359-3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakagoshi, H., C. Kanei-Ishii, T. Sawazaki, G. Mizuguchi, and S. Ishii. 1992. Transcriptional activation of the c-myc gene by the c-myb and B-myb gene products. Oncogene 7:1233-1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ness, S. A., A. Marknell, and T. Graf. 1989. The v-myb oncogene product binds to and activates the promyelocyte-specific mim-1 gene. Cell 59:1115-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oh, I. H., and E. P. Reddy. 1999. The myb gene family in cell growth, differentiation and apoptosis. Oncogene 18:3017-3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sala, A., A. De Luca, A. Giordano, and C. Peschle. 1996. The retinoblastoma family member p107 binds to B-MYB and suppresses its autoregulatory activity. J. Biol. Chem. 271:28738-28740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sala, A., M. Kundu, I. Casella, A. Engelhard, B. Calabretta, L. Grasso, M. G. Paggi, A. Giordano, R. J. Watson, K. Khalili, and C. Peschle. 1997. Activation of human B-MYB by cyclins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:532-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sala, A., and R. Watson. 1999. B-Myb protein in cellular proliferation, transcription control, and cancer: latest developments. J. Cell. Physiol. 179:245-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saleh, M., I. Rambaldi, X. J. Yang, and M. S. Featherstone. 2000. Cell signaling switches HOX-PBX complexes from repressors to activators of transcription mediated by histone deacetylases and histone acetyltransferases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8623-8633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saville, M. K., and R. J. Watson. 1998. B-Myb: a key regulator of the cell cycle. Adv. Cancer Res. 72:109-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saville, M. K., and R. J. Watson. 1998. The cell-cycle regulated transcription factor B-Myb is phosphorylated by cyclin A/Cdk2 at sites that enhance its transactivation properties. Oncogene 17:2679-2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi, Y., M. Downes, W. Xie, H. Y. Kao, P. Ordentlich, C. C. Tsai, M. Hon, and R. M. Evans. 2001. Sharp, an inducible cofactor that integrates nuclear receptor repression and activation. Genes Dev. 15:1140-1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van den Heuvel, S., and E. Harlow. 1993. Distinct roles for cyclin-dependent kinases in cell cycle control. Science 262:2050-2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner, B. L., J. D. Norris, T. A. Knotts, N. L. Weigel, and D. P. McDonnell. 1998. The nuclear corepressors NCoR and SMRT are key regulators of both ligand- and 8-bromo-cyclic AMP-dependent transcriptional activity of the human progesterone receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:1369-1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watson, R. J., C. Robinson, and E. W. Lam. 1993. Transcription regulation by murine B-myb is distinct from that by c-myb. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:267-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ziebold, U., O. Bartsch, R. Marais, S. Ferrari, and K. H. Klempnauer. 1997. Phosphorylation and activation of B-Myb by cyclin A-Cdk2. Curr. Biol. 7:253-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]