Abstract

RGS12TS-S, an 1,157-amino-acid RGS protein (regulator of G protein signaling), is a nuclear protein that exhibits a unique pattern of subnuclear organization into nuclear foci or dots when expressed endogenously or ectopically. We now report that RGS12TS-S is a nuclear matrix protein and identify structural determinants that target this protein to the nuclear matrix and to discrete subnuclear sites. We also determine the relationship between RGS12TS-S-decorated nuclear dots and known subnuclear domains involved in control of gene expression and provide the first evidence that RGS12TS-S is functionally involved in the regulation of transcription and cell cycle events. A novel nuclear matrix-targeting sequence was identified that is distinct from a second novel motif needed for targeting RGS12TS-S to nuclear dots. RGS12TS-S nuclear dots were distinct from Cajal bodies, SC-35 domains, promyelocytic leukemia protein nuclear bodies, Polycomb group domains, and DNA replication sites. However, RGS12TS-S inhibited S-phase DNA synthesis in various tumor cell lines independently of Rb and p53 proteins, and its prolonged expression promoted formation of multinucleated cells. Expression of RGS12TS-S dramatically reduced bromo-UTP incorporation into sites of transcription. RGS12TS-S, when tethered to a Gal4 DNA binding domain, dramatically inhibited basal transcription from a Gal4-E1b TATA promoter in a histone deacetylase-independent manner. Structural analysis revealed a role for the unique N-terminal domain of RGS12TS-S in its transcriptional repressor and cell cycle-regulating activities and showed that the RGS domain was dispensable for these functions. These results provide novel insights into the structure and function of RGS12TS-S in the nucleus and demonstrate that RGS12TS-S possesses biological activities distinct from those of other members of the RGS protein family.

RGS (regulator of G protein signaling) proteins represent a large family of proteins that function as negative regulators of heterotrimeric G protein signaling in organisms ranging from Saccharomyces cerevisiae to humans (7, 17). These proteins were originally defined by the presence of a semiconserved domain of approximately 120 amino acids called the RGS domain (RGD). The discovery that RGS proteins or their RGDs bind in vitro to Gα subunits of the Gi and Gq family and accelerate their intrinsic GTPase activity provided the first insight into how RGS proteins regulate G protein signaling. Although RGS proteins possess the potential to interact with heterotrimeric G proteins, recent evidence suggests that several RGS proteins localize predominantly in the nucleus (3, 5, 6, 8, 11, 18, 29), where G proteins are not thought to localize. These findings raise the fascinating possibility that some members of the RGS protein family may have functions apart from regulatory control of heterotrimeric G protein signaling.

Recently, we reported that RGS12, a member of the RGS protein family, exists in multiple splice variant forms and that these splice variant forms of RGS12 localize exclusively in the nucleus (6). One of these RGS12 splice variants, RGS12TS-S, evoked particular interest due to its unique pattern of subnuclear organization as discrete dots or foci, quite reminiscent of localization of those proteins involved in specialized functions within the nucleus. The underlying molecular mechanism of nuclear import and subnuclear targeting of RGS12TS-S is unknown. The subnuclear targeting of RGS12TS-S raises intriguing questions regarding the significance of such localization in relation to the function(s) of nuclear RGS proteins. In the present study, we addressed the structural basis for subnuclear targeting of RGS12TS-S, the topological characteristics of RGS12TS-S subnuclear sites in relation to previously identified subnuclear structures, and the functional involvement of this RGS protein in the cell nucleus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

pEGFP, IRESpuro2, and pM vectors were purchased from Clontech; the pcDNA3.1 vector was from Invitrogen; and the pGL3 basic vector was from Promega. cDNA encoding human Sp100, human EED (embryonic ectoderm development protein), and human Ring-1 proteins was amplified by PCR from human placental cDNA (Clontech) and cloned into the pCMV Tag2 vector (Stratagene). A c-myc-tagged expression construct of human EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog proteins) was generously provided by T. Jenuwein (Vienna Biocenter, Vienna, Austria). Elongase was from Life Technologies. Antibodies to lamin A/C (636), c-myc (9E10), p130 (C-20), promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) (PG-M3), p27kip1 (F-8), CBP (A-22), and nucleolin (C23 and MS-3) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and antibodies to SC-35 and α-fibrillarin (ANA-N) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Polyclonal antibody to green fluorescent protein (GFP) was from Invitrogen, an antibody to Sm proteins was from NeoMarkers, an antibody to bromouridine-bromodeoxyuridine was from Roche, and a Cy5-conjugated secondary antibody was from Jackson ImmunoResearch. Joseph Gall (Carnegie Institute, Baltimore, Md.) generously provided an antibody to p80 coilin (2). Cell culture media and serum were provided by the Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center (the University of Iowa). Oligonucleotide primers and other molecular biological reagents were obtained from the University of Iowa DNA Core.

Preparation of deletion constructs of RGS12TS.

Recently, we described isolation and cloning of the RGS12TS-S cDNA and subcloning of this cDNA into an enhanced GFP (EGFP) vector with the GFP sequence in frame at the C terminus of RGS12TS-S (6). Similarly, we cloned the RGS12TS-S cDNA into pcDNA3.1 myc/His vector with the c-myc/His sequence in frame with the C terminus of RGS12TS-S. cDNAs encoding RGS12TS-S deletion constructs were generated by PCR using forward primers that deleted indicated amino acids and included a Kozak consensus sequence and ATG start codon for proper translation of the proteins. Reverse primers were selected to amplify RGS12TS-S cDNAs encoding RGS12TS-S proteins lacking various C-terminal sequences. Both forward and reverse primers were engineered with restriction sites for cloning into pEGFP or pcDNA3.1 myc/His to create RGS12TS-S deletion constructs with C-terminal GFP or c-myc sequences, respectively. Double-stranded sequencing of all RGS12TS-S cDNAs was performed by automated fluorescent dideoxynucleotide sequencing by the University of Iowa DNA Core Facility.

Cell culture and transfection.

COS-7, HEK293T, NIH 3T3, and U-2 OS cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and gentamicin (50 μg/ml) in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37°C. MCF7, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, Saos-2, C-33 A, and SW-13 cells were grown in American Type Culture Collection-recommended media. Cells were transfected with plasmid DNA by electroporation or by Lipofectamine Plus reagent (GIBCO) and plated for confocal microscopy or immunoblotting studies as we have previously described (6).

Immunofluorescence.

Cells expressing various RGS12TS-S-GFP constructs were fixed, permeabilized, stained with propidium iodide, and subjected to confocal microscopic visualization as previously described (6). For indirect immunofluorescence, fixed and permeabilized cells were incubated with primary antibodies and fluorescein isothiocyanate- or Cy5-conjugated secondary antibodies also as previously documented (6). Confocal microscopy was performed with a Bio-Rad MRC 1024 confocal microscope equipped with a krypton-argon laser at the University of Iowa Central Microscopy Research Facility. EGFP fluorescence was examined via a fluorescein isothiocyanate filter, propidium iodide fluorescence was examined with a Texas Red filter, and Cy5 fluorescence was examined with a Cy5 filter and 60× oil lenses. Images were captured after Kalman averaging, and pseudocolor processing was performed by use of the Confocal Assistance program. Images shown are representative of a minimum of 500 cells derived from three or more separate transfections. In some experiments, fixed cells were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and examined with a Zeiss fluorescence microscope.

Nuclear matrix preparation and immunoblotting.

Subcellular fractionation of COS-7 cells expressing myc- and GFP-tagged RGS12TS protein constructs was performed as we have previously described (6). Resulting nuclear pellets were used to prepare the nuclear matrix fraction by a published procedure (24). In brief, nuclei were treated at room temperature for 10 min with buffer A {10 mM PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)] (pH 6.8), 100 mM NaCl, 300 mM sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM 4-(2-amino-ethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride, 1 μM leupeptin, 1 μM aprotinin, 1 μM pepstatin, 1 μM bestatin, 1 μM E64, 10 U of RNasin/ml} containing 0.5% Triton X-100. Nuclei were then sedimented by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in buffer A containing 600 U each of the restriction enzymes PstI and HaeIII/ml. Nuclei were incubated for 1 h at 37°C followed by addition of ammonium sulfate to a final 0.25 M concentration. This mixture was centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in buffer A and an equal volume of 4 M NaCl. The resulting suspension was incubated at room temperature for 5 min prior to centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting pellet represented the nuclear matrix fraction. Immunoblotting was performed essentially as we have previously reported (6).

In situ nuclear matrix preparations.

In situ nuclear matrix was prepared essentially as previously described (24). Briefly, COS-7 cells growing in two-chambered glass slides were washed twice with cold Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with buffer A containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 2 to 5 min at 4°C. Cells were then incubated sequentially with buffer A containing 600 U each of PstI and HaeIII/ml for 1 h at 37°C, buffer A containing 0.25 M ammonium sulfate, and buffer A containing 2 M NaCl. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in buffer A for 30 min at room temperature. No detectable staining of nuclei with DAPI was observed in these cells, demonstrating the effective removal of DNA from cells by this procedure. Thus, cell nuclei were visualized by indirect immunofluorescence of lamin A/C.

In situ labeling of DNA replication sites.

COS-7 cells expressing RGS12TS-S-GFP were washed twice with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline followed by incubation in growth medium containing 10 μM bromodeoxyuridine for 45 min or 24 h at 37°C. Cells were fixed by sequential treatment with 70% ethanol and 4 N HCl, and bromodeoxyuridine incorporation into DNA was visualized by indirect immunofluorescence. RGS12TS-S was visualized by indirect immunofluorescence with an antibody that we developed to the N terminus of RGS12TS (6), because the fixation procedure used to identify bromodeoxyuridine-labeled DNA interferes with fluorescence from GFP.

For visualization of DNA synthesis in various human tumor cell lines transfected with RGS12TS-S-GFP, 10 μM bromodeoxyuridine was added to the medium 24 or 48 h following transfection for a period of 20 h. Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100, and treated with DNase I (100 μg/ml) before detection of bromodeoxyuridine-labeled DNA by indirect immunofluorescence, with RGS12TS-S-GFP being identified directly by GFP fluorescence.

In situ run-on transcription.

Labeling of nascent RNA transcripts in situ was performed by a previously published method (26). Briefly, COS-7 cells expressing various RGS12TS-S-GFP constructs were rinsed sequentially with ice-cold TBS (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2) and ice-cold glycerol buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 25% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1 mM 4-(2-amino-ethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride]. Washed cells were incubated briefly with ice-cold glycerol buffer containing Triton X-100 (0.03%) and RNasin (100 U/ml) followed by incubation at room temperature for 25 to 30 min in nucleic acid synthesis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5); 10 mM MgCl2; 150 mM NaCl; 25% glycerol; 1 mM 4-(2-amino-ethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride; 1 μM leupeptin; 1 μM pepstatin; 1 μM aprotinin; 100 U of RNasin/ml; and 0.5 mM (each) ATP, CTP, GTP, and bromo-UTP]. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with Triton X-100-NP-40 (0.1% each), and bromouridine incorporation into RNA was visualized by indirect immunofluorescence.

Reporter gene expression.

Luciferase reporter gene constructs driven by an E1b TATA promoter containing five repeats of the Gal4 binding element (pFR-Luc vector) were obtained from Stratagene. Five repeats of the Gal4 binding element containing the herpesvirus thymidine kinase (TK) promoter or adenovirus minimal late promoter (MLP) (chloramphenicol acetyltransferase reporter constructs provided by D. Ayer, University of Utah) were PCR amplified and cloned in the pGL3 basic vector (Promega). Gal4 DNA binding domain fusion constructs of RGS12TS-S and its various deletion mutants were cloned into the pM vector (Clontech). NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with various DNA constructs by using Lipofectamine Plus reagent according to the manufacturer's suggestions. Luciferase activity in transfected cells was determined with a luciferase assay kit (Promega) 40 h following transfection. Trichostatin A (Sigma) was added to the culture medium at a 500 nM concentration 16 h following transfection. Luciferase activity was normalized for transfected β-galactosidase determined with a Galacto chemiluminescence assay kit (Tropix, Bedford, Mass.).

RESULTS

RGS12TS-S is a nuclear matrix protein.

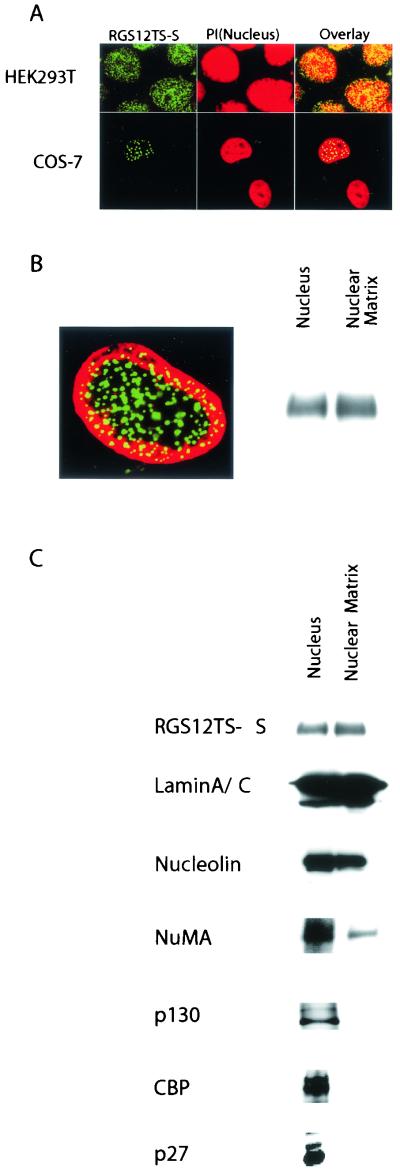

We recently demonstrated that RGS12TS-S is a nuclear protein that exhibits a unique pattern of subnuclear organization into nuclear dots (6). RGS12TS-S exhibits this subnuclear organization as an endogenous protein in HEK293T cells and upon its expression as a GFP fusion protein in COS-7 cells (Fig. 1A ) and in various other cell types (see Fig. 7).

FIG.1.

Subnuclear localization of RGS12TS-S expressed endogenously or ectopically and association of RGS12TS-S with the nuclear matrix. (A) Subnuclear organization of endogenous RGS12TS-S in HEK293T cells and ectopically expressed RGS12TS-S-GFP in COS-7 cells. Green represents RGS12TS-S, and red represents propidium iodide (PI)-stained nuclei (yellow represents overlapping green and red fluorescence). (B) Confocal microscopic overlay image of in situ nuclear matrix preparation of COS-7 cells expressing RGS12TS-S-GFP (green) with lamin A/C antibody-labeled nuclear structures (red) and c-myc immunoblot of nuclear and nuclear matrix fractions of COS-7 cells expressing RGS12TS-S-myc. (C) Immunoblot of RGS12TS-S and various endogenous nuclear proteins in nuclear and nuclear matrix fractions of COS-7 cells expressing RGS12TS-S-myc. Immunofluorescence measurement of endogenously expressed RGS12TS-S in HEK293T cells was performed as described previously (6). Transfection of COS-7 cells, immunofluorescence measurements, subcellular fractionation, and immunoblotting were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

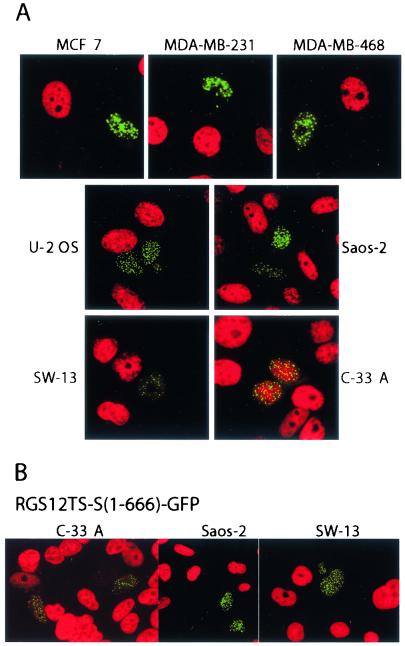

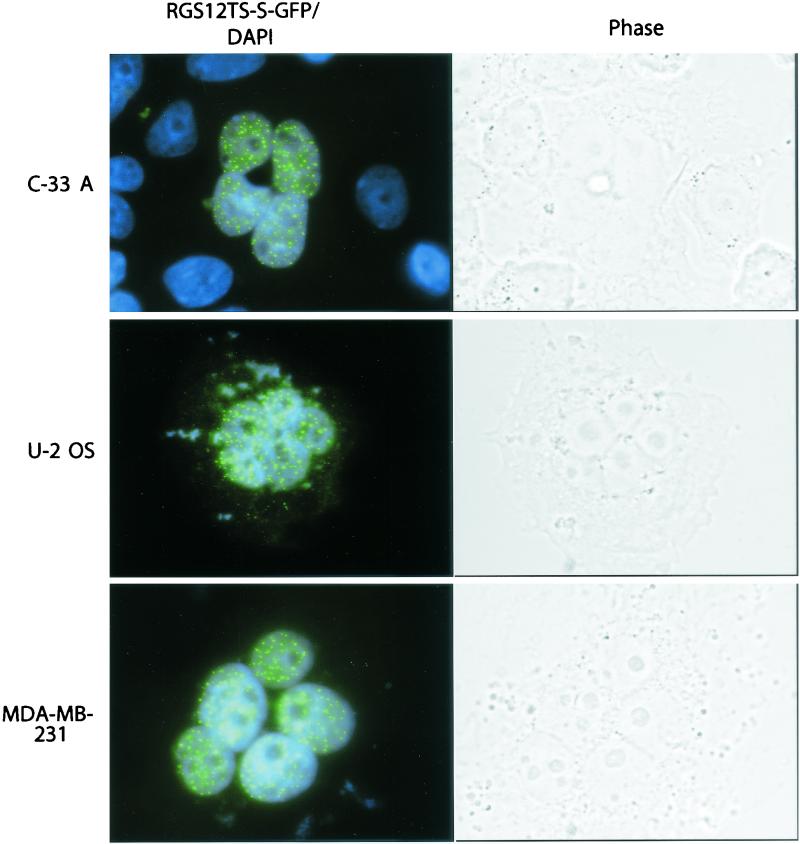

FIG. 7.

RGS12TS-S inhibits DNA synthesis in various human tumor cell lines, and the RGD of RGS12TS-S is not required for this activity. (A) Confocal microscopic images showing various tumor cell lines transfected with RGS12TS-S-GFP (green) and DNA synthesis labeled with bromodeoxyuridine for 20 h (red). (B) Confocal microscopic images of tumor cells expressing RGS12TS-S(1-666)-GFP (green) and bromodeoxyuridine-labeled DNA (red).

Because nuclear matrix structures have been proposed previously to be the underlying structural support for subnuclear organization of various proteins (19), we examined the possible involvement of nuclear matrix structures in the distinctive, dotted subnuclear distribution of RGS12TS-S. Figure 1B shows a confocal microscopic image of an in situ nuclear matrix preparation from COS-7 cells expressing RGS12TS-S-GFP and a corresponding anti-myc immunoblot of nuclear and nuclear matrix preparations from COS-7 cells expressing RGS12TS-S-myc. As shown, RGS12TS-S is retained within the nuclear matrix structure of COS-7 cells and its dotted subnuclear organization remained intact within the nucleoskeletal structure. The corresponding immunoblot shows that RGS12TS-S was recovered in the nuclear matrix fraction of COS-7 cell transfectants, in agreement with the confocal microscopic finding. To verify the authenticity of the nuclear matrix fraction prepared from COS-7 cell transfectants, we examined the distribution of nuclear proteins, some that are known nuclear matrix proteins and others that are not. Figure 1C shows that known nuclear matrix proteins, lamins A and C, nucleolin, and NuMA (nuclear matrix-associated protein/nuclear apparatus protein), fractionated wholly or in part with RGS12TS-S-myc in the nuclear matrix fraction. In contrast, transcriptional regulator p130 of the retinoblastoma family, transcriptional coactivator CBP, and Cdk inhibitor p27kip1 were not retained in the nuclear matrix fraction. The confocal microscopic evidence for retention of RGS12TS-S in the nuclear matrix and the localization of RGS12TS-S in the nuclear matrix fraction demonstrates that RGS12TS-S is a nuclear matrix-associated protein.

Subnuclear and nuclear matrix-targeting domains of RGS12TS-S.

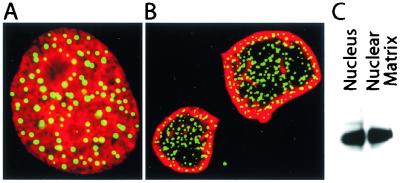

The dotted subnuclear distribution of RGS12TS-S is not shared by other members of the RGS12 protein family or any other member of the RGS protein family. Indeed, we showed that the dotted nuclear distribution of RGS12TS-S is unique to this N-terminal splice variant form of RGS12, as both RGS12B-S and RGS12P-S are distributed homogenously throughout the nucleoplasm (6). Because RGS12TS-S differs from these other splice variant forms of RGS12 by its unique 666-amino-acid N-terminal domain, we hypothesized that this region of RGS12TS-S was responsible for its unique organization within the nucleus. We initiated studies to test this hypothesis by examining the pattern of nuclear distribution of RGS12TS-S(1-685), a construct encoding the unique N-terminal domain of RGS12TS-S and 19 additional amino acids. Indeed, RGS12TS-S(1-685) expressed as a GFP fusion protein showed a pattern of distribution within the nucleus of COS-7 cells (Fig. 2A) that was indistinguishable from that of full-length RGS12TS-S (Fig. 3). Figure 2 also shows an in situ nuclear matrix preparation of COS-7 cells expressing RGS12TS-S(1-685)-GFP and a corresponding immunoblot of nuclear and nuclear matrix preparations of COS-7 cells expressing a myc-tagged form of this N-terminal domain of RGS12TS-S. As shown, RGS12TS-S(1-685), like full-length RGS12TS-S, is retained within the nuclear matrix structure of COS-7 cells with retention of its dotted subnuclear organization within the nucleoskeletal structure (Fig. 2B and C). These results suggest that the necessary structural elements for the subnuclear localization and nuclear matrix targeting of RGS12TS-S are present in its N-terminal domain.

FIG. 2.

Subnuclear localization and nuclear matrix association of an N-terminal domain of RGS12TS-S. (A) Confocal microscopic overlay images of COS-7 cells expressing RGS12TS(1-685)-GFP (green) with propidium iodide-stained nuclei (red). (B) Confocal microscopic image of in situ nuclear matrix preparation of COS-7 cells expressing RGS12TS-S(1-685)-GFP (green) with lamin A/C antibody-labeled nuclear structures (red). (C) c-myc immunoblot of nuclear and nuclear matrix fractions of COS-7 cells expressing RGS12TS-S(1-685)-myc.

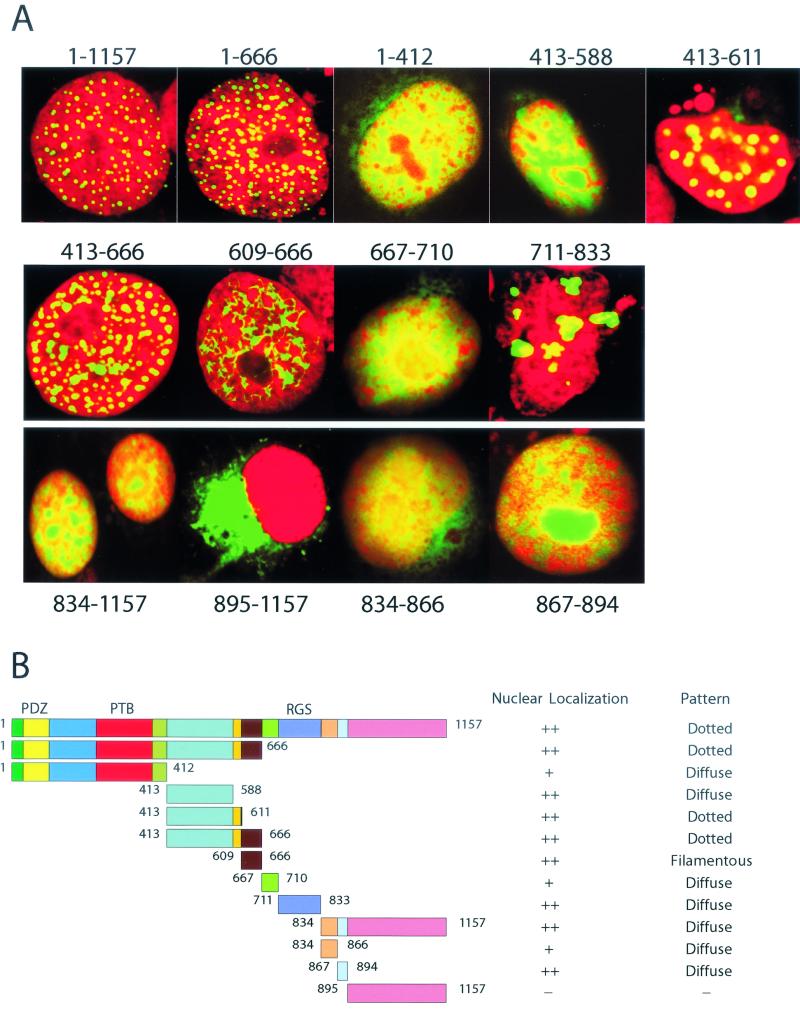

FIG. 3.

Mapping of subnuclear targeting domains of RGS12TS-S. (A) Confocal microscopic overlay images of COS-7 cells expressing GFP-tagged RGS12TS-S or its various deletion constructs. (B) Schematic representation of full-length and deletion constructs of RGS12TS-S and scoring of nuclear localization and pattern of subnuclear distribution.

Mapping of subnuclear targeting domains of RGS12TS-S.

It is likely that distinct processes are involved in promoting nuclear import and subsequent subnuclear targeting of RGS12TS-S. We undertook studies to provide further insight into the structural basis underlying the nuclear and subnuclear localization of RGS12TS-S. Figure 3A shows confocal microscopic images of COS-7 cells expressing full-length RGS12TS-S-GFP or various deletion constructs of RGS12TS-S fused to GFP. The 12 deletion constructs represent contiguous and sometimes overlapping domains of RGS12TS-S that were chosen to evaluate systematically the structural basis for nuclear and subnuclear targeting of RGS12TS-S (Fig. 3B). Figure 3B identifies the region of RGS12TS-S being examined in each construct and the scoring of the nuclear localization and pattern of subnuclear distribution observed.

Mapping of the N-terminal domain of RGS12TS-S.

We first evaluated the nuclear and subnuclear localization of constructs encompassing all or portions of the N-terminal domain unique to RGS12TS-S. Construct 1-666, representing this entire domain, exhibited a pattern of nuclear and subnuclear distribution indistinguishable from that of RGS12TS-S. This result, like that obtained with RGS12TS-S(1-685)-GFP in Fig. 2, suggested that this domain has structural elements for nuclear import and targeting to subnuclear domains. Five additional constructs were prepared to map this region in more detail. Constructs 1-412 and 413-588 showed weaker nuclear localization and diffuse distribution within the nucleus, suggesting that these regions lack sequences needed for subnuclear targeting. However, constructs 413-611 and 413-666 each accumulated in the nucleus and exhibited a dotted pattern of nuclear distribution. The lack of such subnuclear targeting by construct 413-588 suggested that the 23-amino-acid sequence between amino acids 588 and 611 of RGS12TS-S contains necessary structural elements for the dotted pattern of distribution of construct 413-611 and possibly that of construct 413-666. This was confirmed by results obtained with construct 609-666, which exhibited a filamentous or lattice-like pattern of distribution within the nucleus. These results indicated that the region encompassing amino acids 589 to 611 of RGS12TS-S contains sequence elements required for the organization of these protein constructs into nuclear dots.

Mapping of the C-terminal domain of RGS12TS-S.

We next evaluated the patterns of nuclear and subnuclear localization of constructs encompassing portions of the approximate C-terminal half of RGS12TS-S located distal to its unique N-terminal domain. This region of RGS12TS-S is shared entirely by RGS12B-S and RGS12P-S, RGS12 splice variants that exhibit a diffuse pattern of distribution within the nucleus. Inspection of this C-terminal domain for possible nuclear localization sequences (NLSs) showed regions of basic amino acids that could serve as nonclassical NLSs in each of the constructs that we evaluated and the presence of a single prototypic NLS at amino acids 891 to 894 (KKRK) that also conforms to a consensus motif for a nucleolar localization sequence (25). Construct 667-710, representing the region between the unique N terminus of RGS12TS-S and its RGD, localized primarily in the nucleus. Construct 711-833, representing the RGD, also accumulated in the nucleus.

Construct 834-1157, comprising the entire C-terminal domain of RGS12TS-S distal to its RGD, also localized to the nucleus, while construct 895-1157 did not. Further mapping of the region of amino acids 834 to 894 revealed that construct 867-894 predominantly localized within the nucleolus, compared to a weak nuclear localization of construct 834-866. Nucleolar localization of construct 867-894 was confirmed by colocalization of this construct with fibrillarin, a nucleolar marker (data not shown).

Relationship between nuclear matrix- and subnuclear targeting sequences of RGS12TS-S.

Our confocal microscopic results showed that a region encompassing amino acids 589 to 611 of RGS12TS-S was required for the subnuclear organization of various GFP-tagged deletion constructs of this protein into nuclear dots. Indeed, GFP-tagged RGS12TS-S constructs 413-611 and 413-666 localized to these discrete subnuclear sites while RGS12TS-S constructs 1-412, 413-588, and 609-666 did not. Our findings also showed that a construct encompassing amino acids 1 to 685 of RGS12TS-S had necessary structural elements for targeting nuclear dots and the nuclear matrix. However, what remained unclear was whether the subnuclear targeting sequences of RGS12TS-S also represented the nuclear matrix-targeting sequence (NMTS) of this protein. Therefore, we undertook studies to identify the region within the unique N-terminal domain of RGS12TS-S required for targeting the nuclear matrix for comparison to the sequence of RGS12TS-S required for targeting nuclear dots. Nuclear matrix fractions were prepared from COS-7 cells transfected with the same GFP-tagged deletion constructs of RGS12TS-S that were used to identify sequences required for subnuclear targeting of nuclear dots by RGS12TS-S constructs (Fig. 3), and the expressed proteins were detected by immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibody.

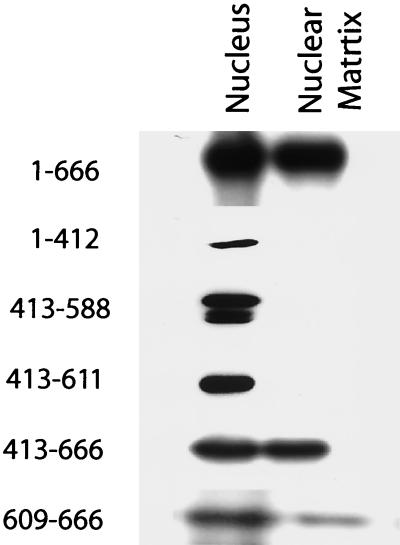

Figure 4 shows the results of these nuclear matrix-targeting studies. As shown, construct 1-666 was retained in the nuclear matrix while constructs 1-412, 413-588, and 413-611 were not. Thus, sequences between amino acids 1 and 611 of RGS12TS-S alone cannot account for association of construct 1-666 with the nuclear matrix. These results, together with the observed retention of construct 413-666 in the nuclear matrix fraction, suggest that the region between amino acids 612 and 666 contributes to the NMTS of these RGS12TS-S constructs. Indeed, construct 609-666 was retained partially in the nuclear matrix fraction. Comparison of this analysis to the structural analysis of subnuclear targeting sequences of RGS12TS-S showed that the structural determinants required for nuclear matrix targeting of RGS12TS-S constructs were distinct from those needed for subnuclear targeting. Indeed, a very clear example of this could be seen in construct 413-611, which showed no nuclear matrix binding (Fig. 4) but localized to nuclear dots like RGS12TS-S itself (Fig. 3). Thus, while we hypothesized that association of RGS12TS-S with the nuclear matrix could potentially underlie its subnuclear organization into nuclear dots, as suggested for several transcription factors and other proteins, our results indicated that this is not the case.

FIG. 4.

Mapping of nuclear matrix-targeting domain in the N-terminal region of RGS12TS-S. Nuclear and nuclear matrix fractions of COS-7 cells expressing GFP-tagged RGS12TS(1-666) or various deletion constructs were subjected to GFP immunoblotting.

Relationship between RGS12TS-S nuclear dots and known nuclear subdomains.

It is now appreciated that the cell nucleus contains several organized domains or substructures that include Cajal bodies, PML domains (alternatively called nuclear domain 10 or PML oncogenic domains), SC-35 domains (nuclear speckles), and Polycomb group (PcG) domains (13, 15, 16, 22). These subnuclear domains accommodate a number of proteins involved in the functional organization of the cell nucleus. An immediate question that arose is whether the subnuclear localization of RGS12TS-S is unique or overlaps with that of known subnuclear domains.

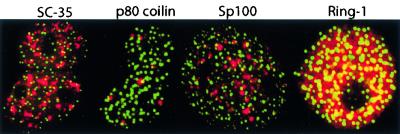

RGS12TS-S subnuclear sites are distinct from sites of RNA processing, PML nuclear bodies, and PcG domains.

We investigated whether RGS12TS-S nuclear dots correspond to SC-35 domains, Cajal bodies, PML nuclear bodies, or PcG domains. Confocal microscopic overlay images of COS-7 cells in Fig. 5 showed subnuclear distribution of GFP-tagged RGS12TS-S in relation to marker proteins for sites of RNA processing, PcG domains, and PML nuclear bodies. As shown, subnuclear structures containing SC-35 and p80 coilin (sites of RNA processing) as well as Sp100 (PML nuclear bodies) and Ring-1 (PcG domains) showed no overlap in distribution with RGS12TS-S subnuclear sites. RGS12TS-S nuclear dots also did not colocalize with two other PcG domain proteins, human EED and human EZH2, when expressed in COS-7 cells (data not shown). RGS12TS-S subnuclear sites also appeared distinct from recently described nuclear bodies (matrix-associated deacetylases), as subnuclear organization of RGS12TS-S is insensitive to inhibitors of histone deacetylase (data not shown). Together, these results demonstrated that RGS12TS-S occupies unique subnuclear sites that are distinct from known subnuclear domains involved in RNA processing and transcriptional regulation.

FIG. 5.

RGS12TS-S subnuclear sites are distinct from known subnuclear domains. Shown are confocal microscopic overlay images of COS-7 expressing RGS12TS-S-GFP (green) and endogenously expressed SC-35, p80 coilin, and coexpressed myc-Sp100 or myc-Ring-1 proteins (red). SC-35 and p80 coilin proteins were detected with specific antibodies, while myc-tagged Sp100 and Ring-1 proteins were detected with an anti-myc antibody.

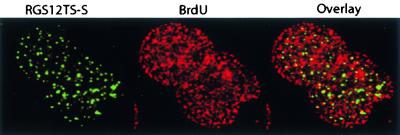

RGS12TS-S does not overlap with DNA replication sites but inhibits S-phase DNA synthesis by p53- and Rb-independent mechanisms.

DNA within the interphase cell nucleus is organized into discrete chromosome territories and replication occurs at fixed sites. Figure 6 shows confocal microscopic images of COS-7 cells expressing RGS12TS-S-GFP in which DNA replication sites were labeled in situ by pulse-labeling with bromodeoxyuridine for 45 min. Few cells expressing RGS12TS-S showed good labeling with bromodeoxyuridine (i.e., compared to untransfected cells), although labeling was more apparent in binucleated cells. As shown, DNA replication sites were organized throughout the nucleus in discrete foci that did not overlap with RGS12TS-S nuclear dots. These results showed that RGS12TS-S is not present at sites of DNA replication in COS-7 cells.

FIG. 6.

RGS12TS-S subnuclear sites are distinct from DNA replication sites. Green represents RGS12TS-S-GFP, and red represents bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU)-labeled (45-min) replication sites. Bromodeoxyuridine labeling of DNA replication sites was performed as described in Materials and Methods.

Because few cells expressing RGS12TS-S were pulse-labeled with bromodeoxyuridine, we examined the possibility that RGS12TS-S expression blocked S-phase DNA synthesis. Therefore, we evaluated S-phase DNA synthesis by labeling COS-7 cells with bromodeoxyuridine for 20 h. We found that over 80% of COS-7 cells expressing RGS12TS-S exhibited no detectable bromodeoxyuridine labeling while cells not expressing RGS12TS-S (i.e., untransfected cells) were uniformly labeled (data not shown). These results showed that cells expressing RGS12TS-S are impaired in S-phase DNA synthesis, which suggests cell cycle-regulatory effects of RGS12TS-S.

To examine the generality and mechanism(s) underlying this response to RGS12TS-S expression, we examined S-phase DNA synthesis in a variety of human tumor cell lines following transient expression of RGS12TS-S. We sought to examine whether RGS12TS-S requires functional Rb or p53 to inhibit S-phase DNA synthesis. Rb and p53 are transcriptional regulators that play critical roles in regulating cell cycle processes. Cell lines derived from human breast adenocarcinoma, human osteosarcoma, human adrenal small cell carcinoma, and human cervical carcinoma were selected for these studies because of their distinct Rb and p53 backgrounds (Table 1). These various cell lines were transfected with RGS12TS-S-GFP, and bromodeoxyuridine labeling (20 h) was initiated 48 h following transfection. Figure 7A shows confocal overlay microscopic images of bromodeoxyuridine incorporation and RGS12TS-S in each of these seven human cell lines. As shown, cells expressing RGS12TS-S uniformly exhibited a lack of bromodeoxyuridine incorporation, with the exception of C-33 A cells, while untransfected cells were robustly labeled. Table 1 summarizes the percentages of RGS12TS-S-GFP-expressing cells that demonstrated a lack of detectable DNA synthesis in these cell lines following bromodeoxyuridine labeling 24 and 48 h posttransfection. As shown, RGS12TS-S expression was associated with a dramatic reduction in DNA synthesis in all cell lines 24 h posttransfection, which persisted in all cells, except C-33 A cells, 48 h posttransfection. As shown, cells with functional Rb and p53 (MCF7 and U-2 OS) appeared equally as sensitive to inhibition of DNA synthesis by RGS12TS-S as were cells lacking p53 (MDA-MB-231) or lacking both Rb and p53 (MDA-MB-468 and Saos-2). These results showed that RGS12TS-S inhibition of S-phase DNA synthesis is cell type independent and occurs by mechanisms independent of Rb and p53. Structural-functional studies of RGS12TS-S showed that constructs encoding the unique N-terminal domain of RGS12TS-S, possessing both NMTSs and subnuclear targeting motifs (Fig. 3 and 4), were sufficient for inhibition of S-phase DNA synthesis (Fig. 7B).

TABLE 1.

Inhibition of bromodeoxyuridine incorporation into DNA in various human tumor cell lines transiently expressing RGS12TS-Sa

| Cell line | Cell type | pRb/p53 | Inhibition of BrdU incorporation in RGS12TS-S transfectants (% cells)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | |||

| MCF7 | Breast | +/+ | 82-97 | 74-80 |

| MDA-MB-231 | Breast | +/+ | 82-84 | 72-78 |

| MDA-MB-468 | Breast | −/− | 74-76 | 69-73 |

| U-2 OS | Osteosarcoma | +/+ | 68-74 | 82-86 |

| Saos-2 | Osteosarcoma | −/− | 58-64 | 48-58 |

| SW-13 | Adrenal | +/? | 60-64 | 65-76 |

| C-33 A | Cervical | −/− | 61-67 | 5-9 |

Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling (10 μM, 20 h) of cells was performed 24 and 48 h following transfection with RGS12TS-S-GFP. At least 200 RGS12TS-S-GFP-expressing cells were examined visually for the presence or absence of bromodeoxyuridine-labeled DNA in each experiment. The results are expressed as percentages of RGS12TS-S transfectants with no detectable bromodeoxyuridine labeling of DNA and are shown as the ranges of two separate experiments. All untransfected cells showed robust labeling of DNA (Fig. 7).

It is intriguing that C-33 A cells were able to bypass RGS12TS-S-induced growth arrest observed 24 h posttransfection (Table 1). These results suggested the existence of compensatory mechanisms that become operative in C-33 A, and perhaps other cells, and facilitate reversal of RGS12TS-S-induced inhibition of S-phase DNA synthesis. To investigate this possibility, we studied the survival and morphology of C-33 A and other cells during prolonged expression of RGS12TS-S. For these experiments, RGS12TS-S-GFP was cloned into a puromycin selection vector for rapid selection of RGS12TS-S-GFP transfectants. One day following transfection, cells were selected by addition of puromycin to the culture. Only RGS12TS-S-GFP transfectants, or cells transfected with vector alone, survived this selection procedure. Cells were examined by fluorescence and phase-contrast microscopy 1 week following transfection (Fig. 8). Irrespective of the cell type that was transfected with RGS12TS-S-GFP, 80 to 90% of RGS12TS-S-GFP transfectants exhibited multiple nuclei, with the remaining cells exhibiting abnormally large or bizarrely shaped nuclei. To illustrate that these morphological changes resulted from RGS12TS-S-GFP expression and were not secondary to the transfection or selection procedure, C-33 A cells transfected with vector alone were mixed with those transfected with RGS12TS-S-GFP, and the cocultured cells are shown in the C-33 A panel (Fig. 8). All RGS12TS-S-GFP transfectants exhibited the typical subnuclear distribution pattern of RGS12TS-S. RGS12TS-S-GFP-expressing cells were larger than normal, and their nuclei had DAPI-stainable DNA, although the multiple nuclei within a given cell showed some variation in DAPI staining patterns. These results showed that RGS12TS-S-GFP-expressing cells can survive for prolonged periods but exhibit morphological features suggesting dysregulation of cell cycle processes. The presence of DAPI-stainable DNA in cells expressing RGS12TS-S-GFP for 1 week indicated that U-2 OS and MDA-MB-231 cells, like C-33 A cells, recover from inhibition of S-phase DNA synthesis observed 24 or 48 h following RGS12TS-S-GFP expression (Fig. 7A; Table 1).

FIG. 8.

Prolonged expression of RGS12TS-S in various human tumor cell lines induces formation of multinucleated cells. (Left) Fluorescence microscopic overlay images of C-33 A, U-2 OS, and MDA-MB-231 cells expressing RGS12TS-S-GFP (green) and DAPI-stained nuclear DNA (blue). (Right) Phase-contrast pictures of cell morphology. In the C-33 A panel, RGS12TS-S-GFP transfectants were mixed with vector-transfected cells for comparison. RGS12TS-S-GFP transfectants were selected with puromycin and at 7 days following transfection were fixed and stained with DAPI. All surviving cells exhibited dotted subnuclear distribution of RGS12TS-S and multinucleation.

RGS12TS-S inhibits transcription in situ and acts as a transcriptional repressor.

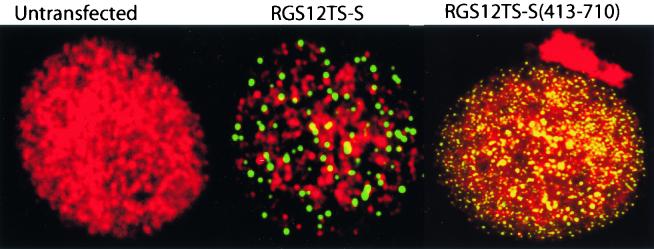

The major cell cycle regulators Rb and p53 and other tumor suppressors such as PML and BRCA1 mediate cell cycle regulation by acting as transcriptional regulators. The observed effects of RGS12TS-S on cell cycle processes and perhaps normal cell division similarly could result from transcriptional regulatory activity(s) of RGS12TS-S. Therefore, we assessed the effects of RGS12TS-S on transcription by in situ transcription runoff and reporter gene assays. Nascent RNA transcripts were labeled with bromo-UTP in COS-7 cells transfected with RGS12TS-S-GFP or mutants thereof. Nontransfected cells from the same microscopic field subjected to identical labeling conditions were used for comparison to RGS12TS-S-GFP-expressing cells. Figure 9 shows representative confocal images of nascent RNA synthesis in nontransfected cells and in cells expressing RGS12TS-S-GFP or RGS12TS(413-710)-GFP. As shown, transcriptionally active sites were organized as dots throughout the nucleoplasm of COS-7 cells and were reduced significantly in cells expressing RGS12TS-S-GFP. Also apparent is the lack of colocalization of RGS12TS-S-GFP with transcription sites. RGS12TS(413-710)-GFP, a construct which contains both the NMTS and subnuclear targeting sequences of RGS12TS-S (Fig. 3 and 4), did not inhibit transcription in situ in COS-7 cells, even when expressed at a much higher level than that of RGS12TS-S-GFP, as shown in Fig. 9. These results suggested that the reduced transcriptional activity in cells expressing RGS12TS-S and its lack of colocalization at sites of transcription likely result from its ability to repress transcription and that sequences outside of amino acids 413 to 710 are required for this effect.

FIG. 9.

RGS12TS-S represses and fails to colocalize with sites of RNA synthesis while RGS12TS-S(413-710) colocalizes with and fails to repress nascent RNA synthesis in COS-7 cells. Shown are confocal microscopic overlay images of RGS12TS-S-GFP- and RGS12TS-S(413-710)-GFP (green)-transfected and nontransfected (control) COS-7 cells with nascent RNA synthesis labeled with bromo-UTP (red).

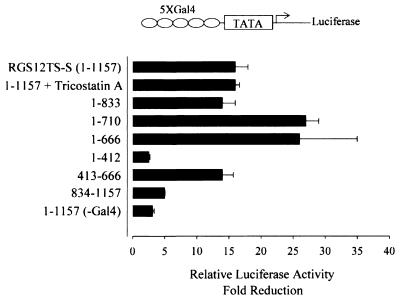

RGS12TS-S could inhibit transcription indirectly by sequestering proteins essential for transcription or by acting directly as a transcriptional repressor by interacting with gene-regulatory elements. To provide insight into the transcriptional repressor activity of RGS12TS-S, we evaluated effects of RGS12TS-S on transcription by using a luciferase reporter gene construct with an E1b minimal TATA promoter. Five repeats of the Gal4 binding element were engineered in front of this promoter (Fig. 10) for targeting of RGS12TS-S and deletion constructs thereof fused to a Gal4 DNA binding domain. The influence of RGS12TS-S and its deletion constructs was evaluated with NIH 3T3 cells, chosen because of the high basal activity of this promoter in these cells. Expression of Gal4-RGS12TS-S elicited a 16- to 20-fold reduction in luciferase activity compared to that for cells expressing the Gal4 DNA binding domain alone (Fig. 10), while expression of RGS12TS-S lacking the Gal4 sequence produced a two- to threefold reduction in luciferase activity. This latter effect may reflect nonspecific effects of RGS12TS-S or effects on sequestering factors needed for basal transcription. Nevertheless, the dramatic inhibition of promoter activity by Gal4-RGS12TS-S demonstrated that this protein represses transcription when targeted to the promoter site of this construct. The RGS12TS-S construct 1-833 was as active as was the full-length protein, while constructs 1-710 and 1-666, which lack the RGD, were even more effective than was the full-length RGS12TS-S in repression of transcription. This latter observation demonstrated that transcriptional repression is independent of the RGD and suggests that the RGD might negatively regulate the transcriptional repressor activity of RGS12TS-S. Further deletion mapping of construct 1-666 revealed that the region from amino acids 1 to 412 had little activity, while construct 413-666 produced a 14-fold reduction in luciferase activity compared to the 26-fold reduction by construct 1-666. These results suggested that the region spanning amino acids 413 to 666 is a major contributor to transcriptional repression by RGS12TS-S. Construct 834-1157, representing the C-terminal domain of RGS12TS-S, had little effect on luciferase activity. Transcriptional repression by RGS12TS-S failed to show any sensitivity to the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A, which demonstrated the lack of histone deacetylase involvement in RGS12TS-S-mediated transcriptional repression.

FIG. 10.

RGS12TS-S represses Gal4-E1b TATA luciferase reporter gene expression. Shown are results for NIH 3T3 cells expressing the Gal4 DNA binding domain alone or its fusion constructs of full-length RGS12TS-S (1-1157) and various deletion constructs of RGS12TS-S along with the luciferase reporter construct. Data are expressed as fold activation of luciferase activity over that observed following expression of the Gal4 DNA binding domain alone. Data are normalized for transfection efficiency by cotransfected β-galactosidase and represent means ± standard errors of the means of three independent experiments. Trichostatin A (500 nM) treatment was performed for 24 h.

In contrast to its effects on repression of basal transcriptional activity, RGS12TS-S had no effects on activated transcription modeled with an adenovirus MLP or herpes virus TK promoter. MLP utilizes Sp1 and TATA sites, and the TK promoter uses Sp1, CCAAT-binding protein, and TATA sites. Both of these promoters exhibit good activity in NIH 3T3 cells. Expression of RGS12TS-S with and without a Gal4 DNA binding domain reduced luciferase activity from MLP by (2.2 ± 0.1)- and (1.9 ± 0.2)-fold, respectively, and from the TK promoter by (3.6 ± 0.1)- and (2.9 ± 0.4)-fold, respectively. These results demonstrated the lack of specific regulatory effects of RGS12TS-S on activated transcription from the MLP and TK promoter, in contrast to its ability to repress transcription from a minimal TATA promoter.

DISCUSSION

The present study documents that RGS12TS-S is a nuclear protein, that it associates with nuclear matrix structures and organizes as subnuclear dots, and that it functionally influences cell cycle processes and represses transcription. This study also delineates structural motifs for nuclear and nuclear matrix localization, dotted subnuclear organization, regulation of cell cycle events, and the transcriptional repressor activity of RGS12TS-S. RGS12TS-S, therefore, represents a constitutive nuclear protein with distinctive subnuclear localization and functions.

We identified unique structural regions within the N-terminal domain of RGS12TS-S required for its dotted subnuclear localization. The characteristic dotted subnuclear organization of RGS12TS-S is reminiscent of subnuclear organization of various nuclear proteins involved in specialized functions including DNA replication, transcription, RNA processing, DNA repair, and gene silencing. It is now becoming increasingly clear that the cell nucleus is functionally compartmentalized and that proteins are targeted to discrete subdomains within the nucleus to perform specialized functions. Nuclear matrix structures provide the underlying support for such spatial organization of nuclear proteins. NMTSs have been identified within several transcription factors including AML-1B (27), Pit-1 (14), glucocorticoid receptor (20), and YY1 (4) as well as in protein kinase A anchoring protein AKAP95 (1). RGS12TS-S, like those nuclear proteins with specialized functions, associates with the nuclear matrix, and we have here identified sequence elements that target RGS12TS-S to nuclear matrix structures. The NMTS of RGS12TS-S and those identified in several other nuclear proteins, however, show no obvious sequence similarities, which suggests that various nuclear proteins utilize diverse NMTSs for their targeting of appropriate sites within the nucleus. It is interesting that the NMTS of RGS12TS-S is distinct from sequence elements involved in its dotted organization. This NMTS targets RGS12TS-S to the nuclear matrix but fails to promote its dotted subnuclear organization. A separate motif is involved in dotted organization of RGS12TS-S. Thus, nuclear matrix targeting and dotted subnuclear organization are clearly independent processes governed by two distinct sequence motifs of RGS12TS-S. This finding is in contrast to a recent report with transcription factor AML-1B, in which a single 31-amino-acid motif was found to promote both nuclear matrix and subnuclear targeting of this transcription factor (27).

The subnuclear sites occupied by RGS12TS-S represent a novel subnuclear compartment distinct from sites occupied by Cajal bodies, SC-35 protein, PcG proteins, and PML nuclear bodies, as well as that involved in DNA replication and synthesis of nascent RNA transcripts. This distinctive pattern of subnuclear targeting of RGS12TS-S suggests that this RGS protein is not directly involved in DNA replication, RNA synthesis and processing, gene silencing like PcG group proteins, or the function of the PML nuclear bodies. Therefore, RGS12TS-S subnuclear structures represent either a novel functional subcompartment of the nucleus or a storage site of certain nuclear proteins destined for shipment to appropriate locales to meet specific cellular needs.

RGS12TS-S expression apparently prevents cell entry into and/or progression through the S phase. It is not clear what step(s) of the cell cycle is the target of RGS12TS-S action in promoting inhibition of S-phase DNA synthesis. However, S-phase block by RGS12TS-S is transient, and cells eventually overcome this block to resume DNA synthesis. Cells escaping S-phase DNA synthesis block continue to be viable, although they invariably exhibit aberrant nuclear morphologies and/or multiple nuclei. Such multinucleated cells could result from multiple rounds of nuclear division without cytokinesis or alternatively from initial endoreduplication and subsequent cell division with a higher DNA content. Previous studies have shown a similar accumulation of multiple and abnormally shaped nuclei following DNA damage in cells lacking the cell cycle regulator p21 (23), ectopic expression of AIM-1 or its kinase-deficient mutant (21), and coexpression of constitutively active Rb and BRG1 in cells lacking BRG1 (28). Mammalian hepatocytes and osteoclasts and early embryos of insects undergo nuclear division without cytokinesis, leading to multinucleated cells as part of normal developmental paradigms (9). The underlying mechanisms of RGS12TS-S-induced cell cycle arrest and dysregulation of cell cycle processes are not clear at present. Nevertheless, our findings provide the initial basis to suggest that RGS12TS-S affects cell cycle progression, leading to multinucleated cells and a decrease in the proportion of cells entering S phase. It is worthwhile to point out that HEK293T cells do not exhibit multinucleated cells, although these cells endogenously express RGS12TS-S. It is possible that HEK293T cells are endowed with or deficient in some factor(s) that allows normal growth even in the continued presence of RGS12TS-S, as is the case with SW-13 and C-33 A cells, which escape Rb-induced growth arrest due to a deficiency in the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling protein BRG1 (28).

The major cell cycle regulators Rb and p53 inhibit cell cycle progression by transcriptional regulation of various components involved in this process. A large network of proteins also indirectly regulates cell cycle progression by influencing the transcriptional regulatory activities of Rb and/or p53. Because RGS12TS-S is competent to influence cell cycle processes even in cells lacking Rb and/or p53, the involvement of Rb and p53 proteins in the mechanism of RGS12TS-S action could readily be ruled out. The demonstration that RGS12TS-S is a transcriptional repressor suggests that cell cycle regulation by RGS12TS-S could be a consequence of this activity. RGS12TS-S is endowed with a single modular domain (amino acids 413 to 666) that functions, when tagged with an appropriate DNA binding domain, as a transcriptional repressor on an E1b TATA promoter. However, on a chromatin-embedded template this domain is not active as a transcriptional repressor unless present in context with sequence module 1-412. This finding indicates that the sequence element within amino acids 1 to 412 targets the repressor domain (amino acids 413 to 666) at appropriate sites to allow repression of transcription from chromatin templates. The sequence element present within amino acids 1 to 412 could bind a DNA sequence that positions the repressor domain in proximity to appropriate promoter sites or could allow its recruitment to appropriate promoter sites via binding to other proteins. This sequence (amino acids 1 to 412) is endowed with known protein binding modules including PDZ and PTB (phosphotyrosine binding) domains, and it remains to be seen whether these modules actually participate in regulating transcriptional repressor activity of RGS12TS-S on chromatin templates. It should be pointed out that the PDZ protein binding module is found only within a limited number of nuclear proteins, including a transcriptional coactivator, TAZ, in the transcriptional coactivator function of which the PDZ domain seems to play an essential role (12). Transcriptional corepressors, like SMRT and N-CoR, are targeted to appropriate promoter sites also through their protein binding modules and in turn recruit ancillary proteins, including histone deacetylase, to inhibit transcription. RGS12TS-S inhibition of transcription, however, does not require histone deacetylase.

The findings that RGS12TS-S localizes within the cell nucleus, represses transcription, and inhibits S-phase DNA synthesis are of particular interest and importance, as they provide the first insight into possible nuclear functions of this protein. Indeed, RGS12TS-S is the first example of an RGS protein with such activities, although combined concomitant transcriptional repressor and cell cycle-regulatory activities are found in p53, Rb, and other tumor suppressor proteins. Interestingly, a recent study showed that RGS12TS-S transcripts are down regulated in human larynx tumors (10), as observed also for tumor suppressor proteins. However, further studies will be required to determine precisely the role of RGS12TS-S in transcriptional repression and cell cycle regulation during normal and abnormal growth, development, and differentiation. Our findings implicate the unique N-terminal domain of RGS12TS-S in its transcriptional repressor and cell cycle-regulating activities and demonstrate that the RGD is entirely dispensable for these functions. These results provide new evidence for modular functional domains of RGS12TS-S, those implicated in nuclear functions and those implicated in interactions with G proteins. While RGS proteins were originally described by the presence of an RGD, the domain required for their ability to inactivate G protein signaling by functioning as GTPase-activating proteins for Gα subunits, Gα subunits have rarely been described within the nucleus, with the sole exception being Gαi2. The present results, therefore, provide evidence for novel and previously unrecognized roles of an RGS family member in the nucleus, which are quite distinct from regulation of cell surface G protein-coupled receptor signaling.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL-41071 (R.A.F.) and DK-25295 (University of Iowa Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center).

We thank John G. Koland for careful reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akileswaran, L., J. W. Taraska, J. A. Sayer, J. M. Gettemy, and V. M. Coghlan. 2001. A-kinase-anchoring protein AKAP95 is targeted to the nuclear matrix and associates with p68 RNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:17448-17454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almeida, F., R. Saffrich, W. Ansorge, and M. Carmo-Fonseca. 1998. Microinjection of anti-coilin antibodies affects the structure of coiled bodies. J. Cell Biol. 142:899-912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burgon, P. G., W. L. Lee, A. B. Nixon, E. G. Peralta, and P. J. Casey. 2001. Phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of a regulator of G protein signaling (RGS10). J. Biol. Chem. 276:32828-32834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bushmeyer, S. M., and M. L. Atchison. 1998. Identification of YY1 sequences necessary for association with the nuclear matrix and for transcriptional repression functions. J. Cell. Biochem. 68:484-499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterjee, T. K., and R. A. Fisher. 2000. Cytoplasmic, nuclear, and Golgi localization of RGS proteins. Evidence for N-terminal and RGS domain sequences as intracellular targeting motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 275:24013-24021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatterjee, T. K., and R. A. Fisher. 2000. Novel alternative splicing and nuclear localization of human RGS12 gene products. J. Biol. Chem. 275:29660-29671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Vries, L., B. Zheng, T. Fischer, E. Elenko, and M. G. Farquhar. 2000. The regulator of G protein signaling family. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 40:235-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dulin, N. O., P. Pratt, C. Tiruppathi, J. Niu, T. Voyno-Yasenetskaya, and M. J. Dunn. 2000. Regulator of G protein signaling RGS3T is localized to the nucleus and induces apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 275:21317-21323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edgar, B. A., and T. L. Orr-Weaver. 2001. Endoreplication cell cycles: more for less. Cell 105:297-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frohme, M., B. Scharm, H. Delius, R. Knecht, and J. D. Hoheisel. 2000. Use of representational difference analysis and cDNA arrays for transcriptional profiling of tumor tissue. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 910:85-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heximer, S. P., H. Lim, J. L. Bernard, and K. J. Blumer. 2001. Mechanisms governing subcellular localization and function of human RGS2. J. Biol. Chem. 276:14195-14203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanai, F., P. A. Marignani, D. Sarbassova, R. Yagi, R. A. Hall, M. Donowitz, A. Hisaminato, T. Fujiwara, Y. Ito, L. C. Cantley, and M. B. Yaffe. 2000. TAZ: a novel transcriptional co-activator regulated by interactions with 14-3-3 and PDZ domain proteins. EMBO J. 19:6778-6791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamond, A. I., and W. C. Earnshaw. 1998. Structure and function in the nucleus. Science 280:547-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mancini, M. G., B. Liu, Z. D. Sharp, and M. A. Mancini. 1999. Subnuclear partitioning and functional regulation of the Pit-1 transcription factor. J. Cell. Biochem. 72:322-338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matera, A. G. 1999. Nuclear bodies: multifaceted subdomains of the interchromatin space. Trends Cell Biol. 9:302-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Misteli, T. 2000. Cell biology of transcription and pre-mRNA splicing: nuclear architecture meets nuclear function. J. Cell Sci. 113:1841-1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross, E. M., and T. M. Wilkie. 2000. GTPase-activating proteins for heterotrimeric G proteins: regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) and RGS-like proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:795-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saitoh, O., I. Masuho, I. Terakawa, S. Nomoto, T. Asano, and Y. Kubo. 2001. Regulator of G protein signaling 8 (RGS8) requires its NH2 terminus for subcellular localization and acute desensitization of G protein-gated K+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 276:5052-5058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stein, G. S., A. J. van Wijnen, J. L. Stein, J. B. Lian, S. H. Pockwinse, and S. McNeil. 1999. Implications for interrelationships between nuclear architecture and control of gene expression under microgravity conditions. FASEB J. 13:S157-S166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang, Y., R. H. Getzenberg, B. N. Vietmeier, M. R. Stallcup, M. Eggert, R. Renkawitz, and D. B. DeFranco. 1998. The DNA-binding and tau2 transactivation domains of the rat glucocorticoid receptor constitute a nuclear matrix-targeting signal. Mol. Endocrinol. 12:1420-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terada, Y., M. Tatsuka, F. Suzuki, Y. Yasuda, S. Fujita, and M. Otsu. 1998. AIM-1: a mammalian midbody-associated protein required for cytokinesis. EMBO J. 17:667-676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Lohuizen, M., M. Tijms, J. W. Voncken, A. Schumacher, T. Magnuson, and E. Wientjens. 1998. Interaction of mouse polycomb-group (Pc-G) proteins Enx1 and Enx2 with Eed: indication for separate Pc-G complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:3572-3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waldman, T., C. Lengauer, K. W. Kinzler, and B. Vogelstein. 1996. Uncoupling of S phase and mitosis induced by anticancer agents in cells lacking p21. Nature 381:713-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wan, K. M., J. A. Nickerson, G. Krockmalnic, and S. Penman. 1999. The nuclear matrix prepared by amine modification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:933-938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber, J. D., M. L. Kuo, B. Bothner, E. L. DiGiammarino, R. W. Kriwacki, M. F. Roussel, and C. J. Sherr. 2000. Cooperative signals governing ARF-Mdm2 interaction and nucleolar localization of the complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:2517-2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei, X., S. Somanathan, J. Samarabandu, and R. Berezney. 1999. Three-dimensional visualization of transcription sites and their association with splicing factor-rich nuclear speckles. J. Cell Biol. 146:543-558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeng, C., A. J. van Wijnen, J. L. Stein, S. Meyers, W. Sun, L. Shopland, J. B. Lawrence, S. Penman, J. B. Lian, G. S. Stein, and S. W. Hiebert. 1997. Identification of a nuclear matrix targeting signal in the leukemia and bone-related AML/CBF-alpha transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:6746-6751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang, H. S., M. Gavin, A. Dahiya, A. A. Postigo, D. Ma, R. X. Luo, J. W. Harbour, and D. C. Dean. 2000. Exit from G1 and S phase of the cell cycle is regulated by repressor complexes containing HDAC-Rb-hSWI/SNF and Rb-hSWI/SNF. Cell 101:79-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang, J. H., V. A. Barr, Y. Mo, A. M. Rojkova, S. Liu, and W. F. Simonds. 2001. Nuclear localization of G protein beta 5 and regulator of G protein signaling 7 in neurons and brain. J. Biol. Chem. 276:10284-10289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]