Abstract

The WT1 tumor suppressor gene is a zinc finger-containing transcription factor which is required for development of the kidney and gonads. A mammal-specific alternative splicing event within this gene results in the presence or absence of a 17-amino-acid sequence within the WT1 protein. To determine the function of this sequence in vivo, gene targeting was utilized to specifically eliminate the exon encoding this sequence in mice. Mice lacking WT1 exon 5 develop normally. Adult mice lacking this exon are viable and fertile, and females are capable of lactation.

The WT1 gene was originally identified as a gene that is deleted or rearranged in many cases of Wilms' tumor (reviewed in reference 23). It encodes a zinc finger-containing nuclear protein with DNA- and RNA-binding activity. Two alternative splicing events within this gene result in the production of four distinct transcripts, and alternative translation start sites and RNA editing result in the production of at least 24 distinct proteins (8). One alternative splicing event results in the presence or absence of a 3-amino-acid sequence, KTS, in the third zinc finger domain of the protein. Proteins lacking this sequence (hereafter referred to as −KTS) demonstrate a diffuse nuclear localization and DNA-binding and transcriptional regulatory activity (23). Isoforms that contain this insertion (hereafter referred to as +KTS) show a punctate nuclear localization (colocalizing with spliceosomes) and impaired DNA-binding and transcriptional regulatory activities (23). The other alternative splicing event results in the presence or absence of a 17-amino-acid sequence between the transcriptional activation and DNA-binding domains. This sequence has been suggested to contain a transcriptional repression domain and is involved in an interaction with the transcriptional regulatory protein Par4 (11, 22). The in vivo function of proteins containing this 17-amino-acid insertion is unknown.

The WT1 gene is expressed in a complex pattern during embryogenesis. It is first detectable in the intermediate mesoderm, which gives rise to the urogenital ridge (1, 3, 20). Expression continues in the urogenital ridge, and it increases in the developing kidney and gonad. In the kidney, expression is observed in the metanephric mesenchyme (which gives rise to the nephron). Expression is upregulated within the portion of the developing nephron that gives rise to the glomerular epithelial cells (1). In the indifferent gonad, WT1 expression is seen in both the coelomic epithelium and the underlying mesenchyme. In the developing testes, WT1 expression becomes limited to the Sertoli cells (1, 20). In the developing ovary, WT1 expression is seen in the cells around the developing follicles. During embryogenesis, WT1 expression is also seen throughout the mesothelial lining of the visceral organs, in the developing spleen, and in a subset of cells in the neural tube. In the adult, WT1 expression is detected in the glomerular epithelial cells of the kidney, the Sertoli cells of the testes, the granulosa cells of the ovary, the ovarian epithelia, the epithelial lining of the oviduct, the uterine stroma, mammary myoepithelial cells, and some mammary epithelial cells (1, 20).

Mutations in the WT1 gene are associated with three distinct syndromes in humans. WAGR syndrome (Wilms' tumor, aniridia, genitourinary anomalies, and mental retardation) is a contiguous gene syndrome that results from hemizygous loss of WT1 and surrounding genes (4, 7). Hemizygous loss of the WT1 gene results in predisposition to Wilms' tumor formation (resulting from further loss of heterozygosity at this locus), genitourinary defects, and predisposition to gonadoblastoma; hemizygous loss of the adjacent pax6 gene results in the aniridia component of this syndrome. Denys-Drash syndrome is caused by point mutations, deletions, or insertions that result in the production of mutated proteins with impaired DNA-binding activity (19). This syndrome is characterized by predisposition to Wilms' tumor, glomerulosclerosis, and genitourinary defects. This phenotype is more severe than the phenotype seen in WAGR syndrome, suggesting that the mutated proteins function as dominant-negative forms of WT1. Frasier syndrome is very similar to Denys-Drash syndrome with regards to the genitourinary defects, but individuals with Frasier syndrome are not predisposed to Wilms' tumor formation. Molecularly, the two syndromes are distinct. Frasier syndrome results from mutations that affect alternative splicing in the third zinc finger domain, resulting in decreased production of the +KTS isoforms of WT1 (2). Thus, mutations in the WT1 gene are associated with defects in urogenital development and function as well as tumorigenesis.

Work with transgenic mice has revealed a great deal about WT1 function during development. Mice completely lacking WT1 function demonstrate complete agenesis of the kidney and gonad, incomplete diaphragm, and abnormal development of the heart, lungs, and spleen (10, 16, 18). Initial development of the metanephric mesenchyme and gonadal ridge occurs in these animals, but subsequent development is arrested (6). Unlike humans, mice heterozygous for this WT1 mutation show no obvious phenotype, except when the mutation is present on a 129/SvJae background, where heterozygous females are infertile (15). Recently, gene targeting has been used to address the role of the +KTS and −KTS isoforms in vivo by creating animals that are incapable of producing one of the two splice forms (9). Heterozygous animals with impaired production of +KTS isoforms of WT1 are viable and fertile but develop proteinuria at approximately 2 to 3 months of age due to glomerulosclerosis. Homozygotes that are incapable of generating either the +KTS or −KTS isoforms develop hypoplastic kidneys with dysgenic glomeruli. The gonads of these animals also develop abnormally. Thus, both +KTS and −KTS isoforms are required for normal kidney and gonadal development. However, the role of the 17-amino-acid sequence in the alternatively spliced exon 5 is unknown.

The functional kidneys of all vertebrates express WT1 during development, and the sequences regulating production of the +KTS and −KTS isoforms are found in all vertebrates examined to date (14). Interestingly, the 17-amino-acid sequence encoded by the alternatively spliced exon 5 is found only in placental mammals (14). Since the functional kidneys of lower vertebrates can form without this exon, this sequence may not be required for kidney or gonadal development. However, this exon may be important for mammal-specific processes such as embryonic implantation or lactation. This possibility is supported by the observation that WT1 is expressed in the uterine stroma, where it is significantly upregulated at the embryonic implantation site (25). WT1 expression is also seen in the adult mammary glands (24). We have recently demonstrated that the uterine stroma predominantly expresses WT1 isoforms containing both the 17-amino-acid sequence and the KTS sequence (15). This observation led us to hypothesize that the 17-amino-acid sequence of exon 5 may be required for embryonic implantation. To test this hypothesis, gene targeting was used to selectively remove exon 5 from the mouse genome. Contrary to our expectations, animals completely lacking this exon are viable, fertile, and capable of lactation, revealing that WT1 exon 5 is not required for any of these functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vector production.

A lambda phage library of mouse 129/SvJae genomic DNA was screened for exon 5-containing clones by hybridization to a 32P-labeled exon 5 probe fragment using standard procedures (16). The targeting construct was generated by cloning a 6-kb SalI-BglII fragment 5′ to exon 5 into the XhoI site of pLNTK and a 3-kb BglII-BglII fragment 3′ to exon 5 into the SalI site of the resulting plasmid. The final targeting plasmid replaces a 350-bp BglII-BglII fragment containing exon 5 with a Pgk-1 promoter-driven neomycin phosphotransferase gene flanked by LoxP sites. A unique NotI site was created to linearize the plasmid prior to electroporation.

ES cell growth.

J1 embryonic stem (ES) cells were cultured, electroporated, and selected as described previously, except for the addition of 1,000 U of leukemia inhibitory factor (Chemicon)/ml to the growth medium (16). For cre-mediated excision of the neomycin selection cassette, targeted ES cells were transiently transfected with the plasmid pMCcre and were plated at low density with no selective agents. Individual colonies were picked and screened as usual (16). ES cells showing the desired targeted mutations were karyotyped by Giemsa staining. Only those colonies with 40 chromosomes in >85% of the cells counted were used for subsequent manipulations.

Genotyping.

Animals were handled in accordance with all federal guidelines and institutional policies. Genomic DNA was isolated from cultured ES cells or tail clippings from animals as described previously (17). For Southern blot analysis, genomic DNA was digested with BamHI and hybridized to a 32P-labeled BglII-Acc65I fragment of mouse genomic DNA from the region immediately 3′ to that used in the targeting construct following standard procedures (16). Under these conditions, wild-type alleles and alleles with a deletion of cre yield a 9-kb band after hybridization, while neo-containing alleles yield a 6-kb band after hybridization. To distinguish wild-type alleles from alleles with a deletion of cre by Southern blot analysis, genomic DNA was digested with EcoRV and hybridized to the targeting probe (giving 10-kb endogenous and 7-kb targeted bands) or to a 3-kb SpeI-BglII fragment derived from the long arm of the targeting vector (giving a 10-kb endogenous or 3-kb targeted band). Primers used for PCR-based genotyping are as follows: exon 5 screen 5′, 5′-ACCACTTCTCAGATTCCCAAC-3′; exon 5 screen 3′, 5′-AGGCAGAGGTAGTACGGTAG-3′; and PGK, 5′-CCATTTGTCACGTCCTGC-3′. For genotyping neo-containing alleles, the three primers were mixed in equimolar ratios; for genotyping alleles with a deletion of cre, only the exon 5 screen 5′ and exon 5 screen 3′ primers were used. PCR was performed as described earlier (6).

Blastocyst injection.

C57BL/6 blastocysts were injected with 15 ES cells each as described earlier (13).

RNA isolation, RNase protection, and Northern blot analysis.

Organs for RNA isolation were dissected free of surrounding tissue and were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen tissue was pulverized with a mortar and pestle under liquid nitrogen, and RNA was isolated as described earlier (5). RNase protection analysis was performed on 20 μg of total RNA from adult testes. A WT1 probe fragment covering nucleotides 1170 to 1755 of the mouse WT1 complementary DNA (cDNA) (+exon 5, +KTS) was subcloned into Bluescript KS(+). 32P-labeled antisense RNA was produced using a MaxiScript in vitro transcription kit as described by the manufacturer (Ambion). RNase protection was performed using the RPAIII RPA kit as described by the manufacturer (Ambion). Protected RNA was electrophoresed on a 4% acrylamide gel containing 8 M urea. Northern blot analysis was performed as described earlier (21). The probes used were as follows: WT1, a Sau3AI-Sau3AI fragment of the mouse WT1 cDNA covering nucleotides 435 to 1936 of the mouse WT1 sequence; and β-actin, a 307-bp fragment of the mouse β-actin gene covering nucleotides 723 to 1029.

Histology.

Tissues samples were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and processed as described earlier (16). Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed as described previously (16).

Sperm counts.

The right epididymis of an adult male mouse was macerated in 1 ml of PBS, and the resulting solution was diluted 1:100 in PBS plus 5 mM EDTA. Sperm heads were counted in a hemocytometer.

RESULTS

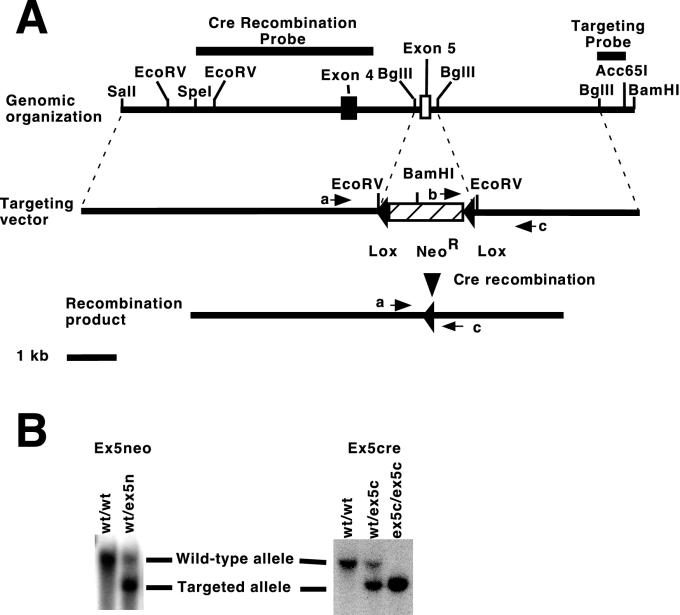

A two-step approach was used to eliminate exon 5 from the mouse genome without disrupting gene function (Fig. 1A). A targeting construct was generated by replacing an approximately 350-bp BglII-BglII fragment from the WT1 gene that contains all of exon 5 with a neomycin resistance cassette flanked by LoxP recognition sequences. Of 170 neomycin- and 1-(1-2-deoxy-2-fluoro-β-d-arabinofuranosyl)-5-iodouracil-resistant colonies screened using Southern blot hybridization, 11 colonies were correctly targeted (data not shown). This allele was designated the WT1ex5n allele. One colony with a normal karyotype was selected to obtain WT1ex5n mice and was also selected to proceed with Cre recombinase-mediated deletion of the neomycin selection cassette. Heterozygous (WT1+/ex5n) males and females were intercrossed, and the resulting pups were genotyped. No homozygous mutant animals (WT1ex5n/ex5n) were obtained. This suggests that the presence of the neomycin phosphotransferase gene disrupts expression of the WT1 gene in these animals. To test this further, WT1+/ex5n males were mated with females heterozygous for the original WT1-targeted mutation. Compound heterozygotes examined at embryonic day 12.5 showed pericardial bleeding, edema, renal agenesis, and gonadal agenesis. Therefore, the compound heterozygotes phenocopy the homozygous WT1-null phenotype. This demonstrates that the WT1ex5n allele functions as a null allele. Therefore, no further characterization of these animals was performed.

FIG. 1.

Gene targeting of WT1 exon 5. (A) Schematic of the WT1 genomic organization and targeting construct. The genomic organization of the WT1 gene is shown with exons 4 and 5 indicated (black and white boxes, respectively). Restriction endonuclease recognition sites are indicated above the line. Probe fragments used to screen for targeting and recombination events are indicated above. The arrows on the diagram of the targeting vector indicate the orientation and approximate location of PCR primer binding sites; a, b, and c represent the exon 5 screen 5′, Pgk, and exon 5 screen 3′ primers, respectively. Restriction endonuclease recognition sequences introduced by the targeting construct are indicated above. A herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase expression cassette was included outside the region of homology to allow selection against randomly integrated plasmids (not shown). At the bottom is a diagram of the targeted WT1 locus following Cre-mediated recombination. PCR primer binding sites are indicated. (B) Genotyping of animals. Southern blot analysis was performed on BamHI-digested tail DNA from animals carrying the neo insertion (ex5neo) or EcoRV-digested tail DNA from animals carrying the allele with a deletion of cre (ex5cre) and hybridized with the targeting probe indicated in panel A. The genotypes of the animals are indicated: wt, wild-type allele; ex5n, ex5n allele; and ex5c, ex5c allele. Arrows indicate the bands derived from the wild-type (wt), ex5n (ex5neo), or ex5c (ex5cre) alleles.

To eliminate the neomycin selection cassette, the selected colony was transiently transfected with the Cre expression vector pMCcre and plated at low density. DNA from individual colonies was screened for recombination by both a PCR genotyping assay and by Southern blot analysis. Of 190 colonies screened, three colonies that had undergone a cre-mediated excision event were identified. Southern blot analysis of BamHI-digested DNAs using pMCcre as a probe failed to reveal any integration of this plasmid into the genome of these cells. This allele was designated the WT1 ex5c allele. These cells were used to generate WT1ex5c-containing animals.

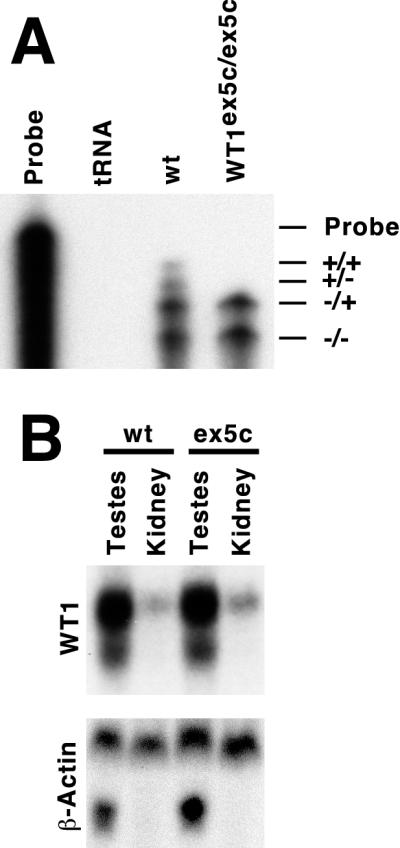

When heterozygous (WT1+/ex5c) animals were intercrossed, the number of wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mutant pups obtained was 77, 166, and 78, respectively, which is at the expected ratios for a nonlethal mutation (chi-square result = 0.38). To confirm that no exon 5-containing transcripts are produced in the WT1ex5c/ex5c mice, RNase protection analysis was performed (Fig. 2). Two bands representing the +exon 5 transcripts are present in RNA samples from the testes of wild-type animals. No +exon 5 transcripts are detected in the WT1ex5c/ex5c animals. Alternative splicing at exon 9 is similar in both wild-type and WT1ex5c/ex5c mice. Northern blot analysis reveals that the overall levels of total WT1 production remain constant, suggesting that the absence of exon 5 exerts no influence on overall WT1 expression levels (Fig. 2). This demonstrates that WT1 exon 5 is not required for viability.

FIG. 2.

Expression of WT1 isoforms. (A) RNase protection analysis of WT1 splice forms. RNase protection was performed using a probe spanning nucleotides 1170 to 1755 of the WT1 +exon 5, +KTS cDNA. The lanes are as follows: probe, probe alone; tRNA, probe hybridized to yeast tRNA; wt, probe hybridized to 20 μg of total testes RNA from a wild-type animal; and WT1ex5c/ex5c, probe hybridized to 20 μg of total testes RNA from a WT1ex5c/ex5c animal. The isoform producing each protected band is indicated to the right: (+/+), + exon 5, +KTS; (+/−), + exon 5, −KTS; (−/+), −exon 5, +KTS; and (−/−), −exon 5, −KTS. Two bands representing the +exon 5 isoforms are detected in wild-type but not WT1ex5c/ex5c samples. No change is seen in the ratio of +KTS to −KTS isoforms in the WT1ex5c/ex5c samples. (B) Northern blot analysis of WT1 expression in WT1ex5c/ex5c animals. Total RNA from wild-type (wt) or WT1ex5c/ex5c (ex5c) testes or kidney hybridized to probes for WT1 or β-actin. No change in WT1 levels is detected.

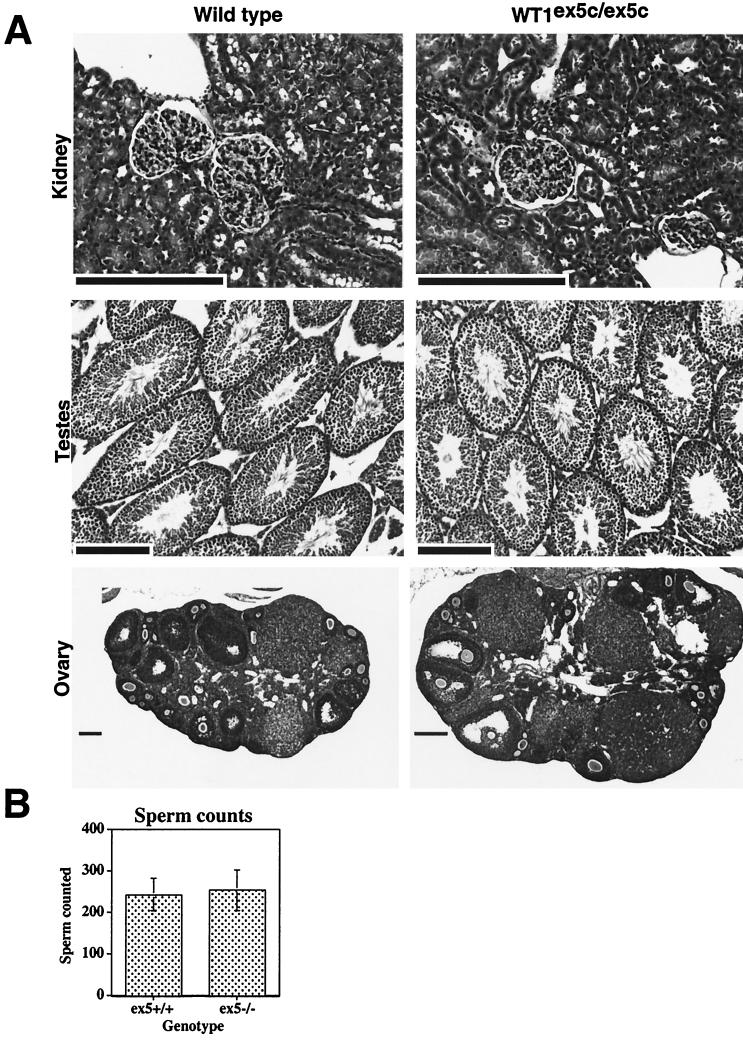

To determine if subtler defects are present in tissues from WT1ex5c/ex5c animals, histological examination was performed on adult animals. No defects were found in the kidneys, testes, ovaries, oviducts, or uteri of WT1ex5c/ex5c animals (Fig. 3 and data not shown). To determine if reproductive function is intact in WT1ex5c/ex5c animals, WT1ex5c/ex5c males were mated with 129/SvJae females and WT1ex5c/ex5c females were mated with C57BL/6J males (Table 1). At least three individuals of each genotype were tested; all had at least one litter. Additionally, when WT1ex5c/ex5c males were mated with WT1ex5c/ex5c females, viable pups were born (data not shown). WT1ex5c/ex5c females nursed their young normally, showing no defects in lactation. Sperm counts were performed on wild-type and WT1ex5c/ex5c males (Fig. 3); no significant difference was noted, and sperm from WT1ex5c/ex5c animals showed normal motility. Finally, compound heterozygotes carrying the original WT1-null allele and the ex5c allele were viable. WT1ex5c/ex5c animals and compound heterozygotes have been observed up to 7 months of age and are apparently normal. Therefore, WT1 exon 5 is not required for viability, fertility, or lactation.

FIG. 3.

Phenotypic analysis of WT1ex5c/ex5c animals. (A) Hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained sections of wild-type or WT1ex5c/ex5c kidney, testes, and ovary are shown. An apparently normal glomerulus is shown in each kidney section. Testes sections show normal spermatogenesis. Ovary sections show ongoing oogenesis and production of corpora lutea. No histological abnormalities are detected. Note that the apparent difference in size between the ovaries is due to differences in the plane of the section, not due to a real size difference. Scale bars are 200 μm. (B) Sperm counts of adult male animals. Epididymal sperm was isolated from three separate wild-type (ex5+/+) or WT1ex5c/ex5c (ex5−/−) animals and counted. The mean of these counts is indicated; error bars indicate the standard deviation.

TABLE 1.

Litter size by parental genotype

| Male genotypea | Female genotypea | Mean litter size ± SD (no. of litters) |

|---|---|---|

| wt/wt | wt/wt | 5.6 ± 1.3 (5) |

| wt/ex5c | wt/ex5c | 4.8 ± 2.0 (6)b |

| wt/wt | ex5c/ex5c | 4.8 ± 1.8 (5)b |

| ex5c/ex5c | wt/wt | 5.0 ± 1.3 (4)b |

wt, wild-type allele; ex5c, ex5c allele.

Difference from wild-type control mating is not statistically significant (P > 0.1).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that exon 5-containing isoforms of WT1 are not required for normal development or reproduction. It is still formally possible that there is a role for WT1 exon 5 in maintenance of organ function; therefore, long-term survival studies are in progress. This alternatively spliced exon is only found in placental mammals; fish, amphibians, reptiles, and birds lack this sequence. Specific deletion of exon 5 has allowed us to test the hypotheses that this sequence is required for mammalian reproduction but not for urogenital development. Here it has been shown that exon 5 is indeed dispensable for urogenital development but, surprisingly, is also dispensable for those reproductive functions specific to mammals.

Alternative splicing of the WT1 gene has long been thought to play an important role in regulating the function of this gene in vivo. A number of assays have revealed differences in the properties of isoforms containing or lacking the KTS insertion in the third zinc finger domain, and gene targeting in mice has recently revealed that both isoforms are required for proper development of the kidney and gonad (9, 23). Since both of these isoforms are conserved in all vertebrates examined to date and since expression in the developing nephric structures and gonad is similarly conserved, it has been proposed that both +KTS and −KTS isoforms have conserved functions in all vertebrates (14).

It has been more difficult to determine if the 17-amino-acid sequence encoded by exon 5 modulates the function of WT1. There are suggestions that this sequence encodes a transcriptional repression domain (11). Recently, it has been shown that this sequence is involved in an interaction between WT1 and another transcription factor, Par4 (22). The functional significance of this interaction is not known. It is possible that exon 5 modulates the activity of WT1 in ways that are not evident during development but may become manifest in disease states. It has been proposed that the sequence encoded by exon 5 is a transcriptional repression domain, and that, therefore, changes in gene expression may occur in these animals. Recent work in mice derived from ES cells or in animals cloned by nuclear transplantation has revealed that even apparently normal animals can display deviation from normal gene expression levels without an obvious effect (12). The availability of animals that lack exon 5 will enable this to be examined directly. This may lead to the identification of previously unrecognized targets of WT1 transcriptional regulatory activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Thompson and H. Ye at the Children's Hospital Mental Retardation Research Gene Manipulation Facility for blastocyst injection, F. Alt for the gift of the pLNTK and pMCcre plasmids, R. Bronson and the Harvard Cancer Center Rodent Histopathology core for help with histological analysis, and J. Ramos for assistance with animal maintenance.

T.A.N. was supported by an American Society for Nephrology/National Kidney Foundation/SangStat fellowship. This work was supported by NIH grant DK50118.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong, J. F., K. Pritchard-Jones, W. A. Bickmore, N. D. Hastie, and J. B. Bard. 1993. The expression of the Wilms' tumour gene, WT1, in the developing mammalian embryo. Mech. Dev. 40:85-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbaux, S., P. Niaudet, M. C. Gubler, J. P. Grunfeld, F. Jaubert, F. Kuttenn, C. N. Fekete, T. N. Souleyreau, E. Thibaud, M. Fellous, and K. McElreavey. 1997. Donor splice-site mutations in WT1 are responsible for Frasier syndrome. Nat. Genet. 17:467-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buckler, A. J., J. Pelletier, D. A. Haber, T. Glaser, and D. E. Housman. 1991. Isolation, characterization, and expression of the murine Wilms' tumor gene (WT1) during kidney development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:1707-1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Call, K. M., T. Glaser, C. Y. Ito, A. J. Buckler, J. Pelletier, D. A. Haber, E. A. Rose, A. Kral, H. Yeger, and W. H. Lewis. 1990. Isolation and characterization of a zinc finger polypeptide gene at the human chromosome 11 Wilms' tumor locus. Cell 60:509-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chomczynski, P., and N. Sacchi. 1987. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 162:156-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donovan, M. J., T. A. Natoli, K. Sainio, A. Amstutz, R. Jaenisch, H. Sariola, and J. A. Kreidberg. 1999. Initial differentiation of the metanephric mesenchyme is independent of WT1 and the ureteric bud. Dev. Genet. 24:252-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gessler, M., A. Poustka, W. Cavenee, R. L. Neve, S. H. Orkin, and G. A. Bruns. 1990. Homozygous deletion in Wilms tumours of a zinc-finger gene identified by chromosome jumping. Nature 343:774-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haber, D. A., R. L. Sohn, A. J. Buckler, J. Pelletier, K. M. Call, and D. E. Housman. 1991. Alternative splicing and genomic structure of the Wilms tumor gene WT1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:9618-9622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammes, A., J. K. Guo, G. Lutsch, J. R. Leheste, D. Landrock, U. Ziegler, M. C. Gubler, and A. Schedl. 2001. Two splice variants of the Wilms' tumor 1 gene have distinct functions during sex determination and nephron formation. Cell 106:319-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herzer, U., A. Crocoll, D. Barton, N. Howells, and C. Englert. 1999. The Wilms tumor suppressor gene wt1 is required for development of the spleen. Curr. Biol. 9:837-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewitt, S. M., and G. F. Saunders. 1996. Differentially spliced exon 5 of the Wilms' tumor gene WT1 modifies gene function. Anticancer Res. 16:621-626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humpherys, D., K. Eggan, H. Akutsu, K. Hochedlinger, W. M. Rideout III, D. Biniszkiewicz, R. Yanagimachi, and R. Jaenisch. 2001. Epigenetic instability in ES cells and cloned mice. Science 293:95-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joyner, A. L. 1993. Gene targeting: a practical approach. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 14.Kent, J., A. M. Coriat, P. T. Sharpe, N. D. Hastie, and V. van Heyningen. 1995. The evolution of WT1 sequence and expression pattern in the vertebrates. Oncogene 11:1781-1792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreidberg, J. A., T. A. Natoli, L. McGinnis, M. Donovan, J. D. Biggers, and A. Amstutz. 1999. Coordinate action of Wt1 and a modifier gene supports embryonic survival in the oviduct. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 52:366-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreidberg, J. A., H. Sariola, J. M. Loring, M. Maeda, J. Pelletier, D. Housman, and R. Jaenisch. 1993. WT-1 is required for early kidney development. Cell 74:679-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laird, P. W., A. Zijderveld, K. Linders, M. A. Rudnicki, R. Jaenisch, and A. Berns. 1991. Simplified mammalian DNA isolation procedure. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:4293.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore, A. W., L. McInnes, J. Kreidberg, N. D. Hastie, and A. Schedl. 1999. YAC complementation shows a requirement for Wt1 in the development of epicardium, adrenal gland and throughout nephrogenesis. Development 126:1845-1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelletier, J., W. Bruening, C. E. Kashtan, S. M. Mauer, J. C. Manivel, J. E. Striegel, D. C. Houghton, C. Junien, R. Habib, L. Fouser, et al. 1991. Germline mutations in the Wilms' tumor suppressor gene are associated with abnormal urogenital development in Denys-Drash syndrome. Cell 67:437-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pelletier, J., M. Schalling, A. J. Buckler, A. Rogers, D. A. Haber, and D. Housman. 1991. Expression of the Wilms' tumor gene WT1 in the murine urogenital system. Genes Dev. 5:1345-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pruitt, S. C., and T. A. Natoli. 1992. Inhibition of differentiation by leukemia inhibitory factor distinguishes two induction pathways in P19 embryonal carcinoma cells. Differentiation 50:57-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richard, D. J., V. Schumacher, B. Royer-Pokora, and S. G. Roberts. 2001. Par4 is a coactivator for a splice isoform-specific transcriptional activation domain in WT1. Genes Dev. 15:328-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scharnhorst, V., A. J. van der Eb, and A. G. Jochemsen. 2001. WT1 proteins: functions in growth and differentiation. Gene 273:141-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silberstein, G. B., K. Van Horn, P. Strickland, C. T. Roberts, Jr., and C. W. Daniel. 1997. Altered expression of the WT1 Wilms tumor suppressor gene in human breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:8132-8137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou, J., F. J. Rauscher III, and C. Bondy. 1993. Wilms' tumor (WT1) gene expression in rat decidual differentiation. Differentiation 54:109-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]