Abstract

Blood vessel recruitment is an important feature of normal tissue growth. Here, we examined the role of Akt signaling in coordinating angiogenesis with skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Hypertrophy of C2C12 myotubes in response to insulin-like growth factor 1 or insulin and dexamethasone resulted in a marked increase in the secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Myofiber hypertrophy and hypertrophy-associated VEGF synthesis were specifically inhibited by the transduction of a dominant-negative mutant of the Akt1 serine-threonine protein kinase. Conversely, transduction of constitutively active Akt1 increased myofiber size and led to a robust induction of VEGF protein production. Akt-mediated control of VEGF expression occurred at the level of transcription, and the hypoxia-inducible factor 1 regulatory element was dispensable for this regulation. The activation of Akt1 signaling in normal mouse gastrocnemius muscle was sufficient to promote myofiber hypertrophy, which was accompanied by an increase in circulating and tissue-resident VEGF levels and high capillary vessel densities at focal regions of high Akt transgene expression. In a rabbit hind limb model of vascular insufficiency, intramuscular activation of Akt1 signaling promoted collateral and capillary vessel formation and an accompanying increase in limb perfusion. These data suggest that myogenic Akt signaling controls both fiber hypertrophy and angiogenic growth factor synthesis, illustrating a mechanism through which blood vessel recruitment can be coupled to normal tissue growth.

Skeletal muscle hypertrophy plays an important role in normal postnatal development and the adaptive response to physical exercise (20). This process is associated with blood vessel recruitment, such that capillary density is either maintained or increased in the growing muscle (14, 15, 30, 34). Conversely, myofiber atrophy that occurs with aging, disuse, and myopathic disease is associated with capillary loss (8, 28). It has been shown that angiogenesis and compensatory muscle hypertrophy are temporally coupled, suggesting that these two processes may be controlled by common regulatory mechanisms (47). However, nothing is known about the molecular events that coordinate myofiber hypertrophy and the recruitment of new blood vessels.

Akt is a serine-threonine protein kinase that is activated by various extracellular stimuli through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase) pathway (13). Numerous studies have implicated Akt signaling in the control of organ size and cellular hypertrophy (9, 71). With mammalian cell cultures, it has been shown that an oncogenic Akt-Gag fusion protein promotes glucose transport and protein synthesis in L6 myotubes (69) and that constitutive activation of Akt signaling promotes a hypertrophic phenotype in muscle both in vitro (52) and in vivo (6). Similarly, Akt signaling has also been shown to control the smooth muscle cell hypertrophy that is associated with hypertension (27, 70), and PI 3-kinase signaling has been implicated in cardiac myocyte hypertrophy (61).

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is an endothelial cell-selective mitogen that has an important role in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis (18). In vivo, VEGF expression patterns coincide spatially and temporally with blood vessel growth under both physiological and pathological conditions. Although high levels of VEGF are constitutively expressed in many tumors, its expression in nontransformed cells is tightly regulated by hypoxia, cytokines, or growth factors. The regulation of VEGF production by hypoxia occurs through the action of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) on the VEGF promoter (57) and by hypoxia-mediated increases in mRNA stability (29) and protein translation (64). In addition, a proximal G+C-rich element in the promoter is essential for VEGF induction by cytokines and contributes to the constitutive VEGF expression that is seen in tumors (46, 55, 60, 66).

To understand how angiogenesis is coordinated with Akt-mediated tissue growth, we examined the role of myogenic Akt signaling in controlling VEGF production and blood vessel recruitment under conditions of myofiber hypertrophy. The first purpose of this study was to examine the role of Akt signaling in VEGF production during myofiber hypertrophy in vitro. Next, we examined whether myogenic Akt signaling could activate VEGF synthesis in vivo and assessed whether Akt activation was sufficient to promote angiogenesis and perfusion in a hind limb model of vascular insufficiency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Protein concentrations were determined by using bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagent from Pierce (Rockford, Ill.). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), trypsin, fetal bovine serum (FBS), and penicillin-streptomycin mixture were obtained from Life Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, Md.). Insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and insulin were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals (Indianapolis, Ind.), and dexamethasone was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, Calif.). All other chemicals and reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). Mouse VEGF, bovine fibroblast growth factor, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor levels in cell culture media or mouse sera were determined with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) used according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Cell lines and culture conditions.

C2C12 myoblasts (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured as described elsewhere (21). Cells were maintained in growth medium (DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS). To induce differentiation, cells were shifted to differentiation medium (DMEM supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated horse serum). To induce myofiber hypertrophy, differentiation medium was supplemented with IGF-I (200 ng/ml) or insulin and dexamethasone (1 and 2.5 μM, respectively) (I/D) (58). Passaged human skeletal muscle cells and vascular smooth muscle cells were obtained from Clonetics (Walkersville, Md.) and grown according to the directions of the manufacturer. Hypoxia was generated by using a GasPak Plus system (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.) and monitored with anaerobic indicator strips (Becton Dickinson).

Adenovirus vector construction and infection.

Replication-defective adenovirus constructs expressing β-galactosidase (Adeno-βgal), dominant-negative mutant Akt (T308A, S473A) (Adeno-dnAkt), and constitutively active Akt (Adeno-myrAkt) were described previously (24). All constructs were amplified in 293 cells and purified by ultracentrifugation. Viral titers were determined as PFUs. For infection, C2C12 cells were typically incubated with adenovirus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 250 PFU in differentiation medium for 12 h. The virus was removed when the medium was replaced with fresh differentiation medium or differentiation medium containing IGF-I or I/D. Under these conditions, the transfection efficiency was greater than 90%.

Western immunoblotting.

The following antibodies were used in the present study: anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473), anti-phospho-p70S6 kinase, and anti-Akt were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, Mass.); anti-CDK4 and anti-p70S6 kinase were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, Calif.); anti-hemagglutinin (HA) antibody was obtained from Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Indianapolis, Ind.); and anti-β-galactosidase antibodies were obtained from Oncogene Research Products (Boston, Mass.). Cell lysates were prepared with an ice-cold lysis buffer containing the following (in millimoles per liter, unless otherwise indicated): Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 50; NaCl, 137; EDTA, 5; NaF, 100; β-glycerophosphate, 10; dithiothreitol, 1; phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1; 1% Nonidet P-40; 10 μg of aprotinin/ml; and 10 μg of leupeptin/ml. Equal amounts of protein were electrophoresed on polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20, and immunoblotting was performed with antibodies at 1 μg/ml. Positive antibody reactions were visualized with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Amersham Pharmacia). The peroxidase reaction was developed by using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Pharmacia). The same membrane was reprobed for detection of a different antibody after treatment of the membrane with Restore Western blot stripping buffer (Pierce). In some instances, band intensities were scanned for quantitation with NIH Image software.

DNA and protein synthesis assays.

DNA synthesis was measured as [3H]thymidine (Amersham Pharmacia) incorporation (62). Protein synthesis was measured as l-[4,5-3H]leucine (Amersham Pharmacia) incorporation. C2C12 cells were plated in 24-well plates and cultured in growth medium. At subconfluence, the medium was changed to differentiation medium, and the cells were cultured for 12 h. Then, the cells were infected with adenovirus vectors at an MOI of 250 for 12 h. After infection, the medium was replaced with DMEM containing either 2% horse serum, 2% horse serum with IGF-I, or 2% horse serum with I/D. After 3 days, [3H]thymidine (1.0 μCi/well) with nonlabeled thymidine (2 μM) or l-[4,5-3H]leucine (0.25 μCi/well) was added to the cells. After 24 h, the cells were washed twice with PBS, 10% trichloroacetic acid was added to each well, and the cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C. The pellets were washed twice with 5% trichloroacetic acid and then suspended in 0.25 N NaOH. [3H]thymidine or l-[4,5-3H]leucine incorporation was determined by scintillation counting.

Determination of lactate and LDH.

Extracts were prepared from cells growing in a 35-mm dish by adding 400 ml of PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100. To measure lactate levels, 1 ml of lactate reagent solution (Sigma) was added to 100 μl of cell extract, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The absorbance was recorded at 540 nm. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity was measured by adding 100 μl of cell extract to 1 ml of pyruvate substrate solution (Sigma). Reactions were initiated with NADH, and reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Following the addition of Sigma color reagent and 0.4 N sodium hydroxide, the absorbance at 525 nm was determined.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from cultured C2C12 cells by using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) as described by the manufacturer. VEGF mRNA expression was assayed by Northern blot analysis of reaction products obtained with a reverse transcription (RT)-PCR kit for VEGF (Ambion, Austin, Tex.). Before cDNA synthesis, 1.0 μg of total RNA was incubated at 65°C for 3 min and then immediately cooled on ice. This RNA was added to a 20-μl RT cocktail containing 4 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphate mixture, 2 μl of random decamer primer, 1 μl of RNase inhibitor, and 100 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase, and the mixture was incubated at 42°C for 1 h. The cDNA was kept at −20°C until used for PCR analysis. cDNA (1 μl) was used as a template for each PCR amplification. Each 50-μl reaction mixture contained deoxynucleoside triphosphates (0.2 mM each), [α-32P]dCTP (5 μCi), VEGF primer pair (0.4 μM each), 18S Primer-Competimer mix (3:7), and thermostable DNA polymerase (1 U) in PCR buffer. After an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 3 min, the reactions underwent 19 cycles at 94°C (30 s), 59°C (1 min), and 72°C (1 min) in an MJ Research thermocycler. PCR products were analyzed on a 6% acrylamide-8 M urea gel, which was dried and exposed to X-ray film. The image was captured electronically, and the bands were quantified by using image analysis software (NIH Image). 18S rRNA was used as a control for the amount of cDNA present in each amplification reaction.

RNase protection assays.

Human skeletal muscle cell cultures were incubated with adenovirus at an MOI of 250 PFU or mock infected for 12 h. The virus was removed by the addition of fresh medium. After 48 h of incubation, total RNA was isolated by using an RNeasy minikit, and total RNA (20 μg) was analyzed for distinct mRNA by using a RiboQuant multiprobe RNase protection assay system with a human angiogenesis multiprobe template set (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.). The antisense RNA probes can hybridize with target human mRNAs encoding FLT1, FLT4, TIE, thrombin receptor, TIE2, CD31, endoglin, angiopoietin 1, VEGF, and VEGF-C. RNase-treated samples were analyzed on a 5% acrylamide-7 M urea gel, which was dried and exposed to X-ray film.

DNA transfection.

The VEGF promoter-reporter constructs used in transient transfection assays contain sequences from the human VEGF promoter upstream of the firefly luciferase gene (42). Transient transfection was performed with SuperFect transfection reagent (Qiagen) by using protocols provided by the manufacturer. Cells were cotransfected with a promoter-reporter construct, an Akt expression plasmid, and a β-galactosidase expression plasmid to normalize for transfection efficiency. C2C12 cells were seeded in six-well plates and incubated with growth medium. At approximately 70% confluence, the medium was changed to differentiation medium, and the cells were incubated for another 12 h. Cells were incubated with DNA-SuperFect mixture for 3 h, and the mixture was replaced with IGF-I or not replaced. At 48 h after transfection, cell extracts were prepared by using luciferase cell culture lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and assessed for luciferase (Promega) and β-galactosidase (Galacto-Star; Tropix) activities. To examine the effects of hypoxia on promoter activity, cells were incubated under nonhypoxic conditions for 36 h followed by 12 h of hypoxia prior to extract preparation.

Mouse model.

C57BL/6 male mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) were 2 months old and weighed 25 to 30 g. The right gastrocnemius muscle of anesthetized mice was injected with four 25-μl doses of saline alone or saline plus 1010 PFU of Adeno-βgal, an adenovirus vector expressing the mouse Vegf cDNA from the cytomegalovirus promoter (Adeno-VEGF), or Adeno-myrAkt/ml (three mice for the saline group and six mice for each viral treatment group and each time point). Gastrocnemius muscle was harvested 14 days after injection, fixed in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, Calif.), and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Serial cryostat sections (8 μm) were fixed for 3 min in 4% paraformaldehyde. Muscle sections were incubated in X-Gal substrate [0.5 mg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside/ml, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM K3Fe(CN)6-K4Fe(CN)6 in PBS] overnight at 37°C and then counterstained with hematoxylin. Tissue sections were also fixed and stained with goat anti-Akt1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rat monoclonal anti-mouse CD31 (Pharmingen), or rabbit polyclonal anti-VEGF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies. Primary antibody dilutions were incubated overnight at 4°C, incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody for 30 min at room temperature, and incubated with streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase and fast red chromogen solution (Dako, Carpinteria, Calif.) at room temperature. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Myofiber area in tissue sections was measured by using NIH Image software (version 1.61). Approximately 100 myofiber cross sections were analyzed in each study group (saline, selected at random; Adeno-βgal, blue myocytes; Adeno-myrAkt, red myocytes). Blood was obtained by heart puncture, and red blood cells were removed by centrifugation.

Rabbit model.

The left femoral artery and side branches were completely excised from their proximal origin to the point distally where bifurcation occurs in male New Zealand White rabbits weighing 3.0 to 3.5 kg. After 10 days to permit postoperative recovery, 3.5 × 1010 particles of Adeno-myrAkt or Adeno-βgal in 2.5 ml of saline were injected through a 27-gauge needle at a depth of 3 to 5 mm into the adductor (two sites), medial large (two sites), and semimembranous (one site) muscles (500 μl per injection site). Mock-infected animals received 2.5 ml of saline at these same sites. Collateral arteries were evaluated by internal iliac angiography at 10 and 40 days postsurgery by using a 3-F infusion catheter (Tracker-18; Target Therapeutic, San Jose, Calif.). This catheter was introduced into the common carotid artery and advanced to the internal iliac artery of the ischemic limb by using a 0.014-in. guide wire (Cardiometrics, Inc., Mountain View, Calif.) under fluoroscopic guidance. Nonionic contrast medium (Isovue-370; Squibb Diagnostics, New Brunswick, N.J.) was injected at a rate of 1 ml/s, and serial images were recorded for 10 s at a rate of one film per second. Quantitative angiographic analysis of collateral vessels was performed by placing a 4-s angiogram over a grid composed of 2.5-mm-diameter circles arranged in rows spaced 5 mm apart. The angiographic score was calculated as the number of circles crossed by a visible collateral vessel divided by the total number of circles encompassed by the outline of the medial thigh. Calf blood pressure was measured in both limbs with a Doppler flow meter (model 1059; Parks Medical Electronics, Aloha, Oreg.) at 10 and 40 days postsurgery. The calf blood pressure ratio was defined as the ratio of the left calf systolic pressure to the right calf systolic pressure. Intravascular Doppler flow measurements in the internal iliac artery of the ischemic limb were performed at 10 and 40 days postsurgery by using a 0.018-in. Doppler guide wire (Cardiometrics). This wire was advanced through a 3-F infusion catheter to the internal iliac artery of the ischemic limb. Average peak velocity (APV) was recorded after a bolus injection of 2 mg of papaverine through the infusion catheter. Angiographic luminal diameter (d) was determined from the angiograms, and Doppler flow (QD, in milliliters per minute) was calculated as follows: QD = (πd2/4)(0.5APV). Capillary density in the adductor muscle was evaluated after animal sacrifice at 40 days postsurgery. Muscle samples were embedded in OCT compound and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen sections (5 μm) were stained for alkaline phosphatase by using indoxyltetrazolium and then counterstained with 0.5% eosin. The capillary density was calculated as the average number of capillaries per square millimeter from 10 randomly selected microscopic fields.

Statistical analyses.

Data were analyzed by using either Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance followed by Fisher's test.

RESULTS

Akt signaling is essential for myotube hypertrophy.

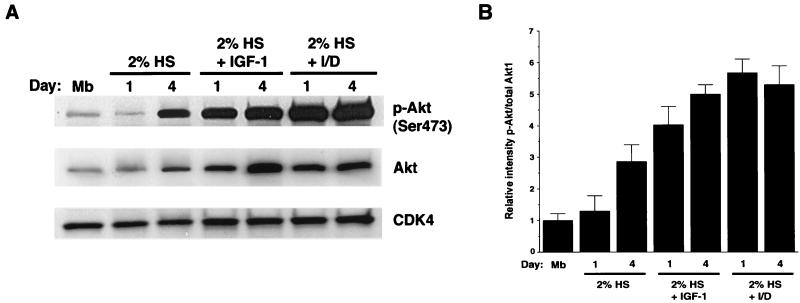

Initially, we examined changes in Akt1 expression and phosphorylation in differentiating cultures of C2C12 skeletal muscle cells under a variety of cell growth conditions. For these studies, myoblast differentiation to myotubes was induced by changing the medium from growth medium (DMEM with 20% FBS) to differentiation medium (DMEM with 2% horse serum) in the presence or absence of IGF-I or I/D. Myoblast cultures incubated briefly in differentiation medium for 30 min or 1 day exhibited a relatively low level of Akt phosphorylation on serine residue 473 (Fig. 1A), a property which is indicative of the status of Akt activation (1, 67). The inclusion of IGF-I or I/D in the differentiation medium led to a marked increase in Akt phosphorylation at day 1. Incubation with IGF-I or I/D also led to an increase in the level of total Akt protein, consistent with prior observations of the myogenic induction of Akt1 and Akt2 (2, 3, 21, 22). A higher level of Akt phosphorylation was also observed in cultures that were maintained in simple differentiation medium for 4 days, presumably due to autocrine stimulation by IGFs secreted by differentiating cultures (19, 26, 53, 68). To determine the relative increase in the fraction of phosphorylated Akt relative to total Akt under these conditions, four independent experiments were performed and Western blot band intensities were quantified. As shown in Fig. 1B, the level of phosphorylated Akt relative to total Akt was increased at day 4 in simple differentiation medium, but a higher level of phosphorylated Akt was detected at day 1 when IGF-I or I/D was included in the medium.

FIG. 1.

Effects of IGF-I and I/D on Akt phosphorylation. (A) C2C12 cells were plated on 60-mm dishes and cultured in growth medium. When the cells reached partial confluence, the medium was replaced with differentiation medium, differentiation medium with IGF-I, or differentiation medium with I/D. HS, horse serum. Cells were harvested on the indicated day. Myoblast (Mb) cultures were switched to differentiation medium for 30 min prior to harvest and analysis. Immunoblot analysis was performed with anti-phospho-Akt (p-Akt), anti-total Akt1, and anti-CDK4 antibodies. In this experiment, we used an anti-phospho-Akt antibody which recognizes phosphorylation within the activation loop at Ser473. (B) Quantitative analysis of the level of phosphorylated Akt relative to the level of total Akt. Band intensities for phosphorylated Akt and total Akt1 were determined from four different experiments. Results are expressed as the mean level of phosphorylated Akt/total Akt and the standard error of mean. The fraction of phosphorylated Akt in myoblasts was set at 1.0.

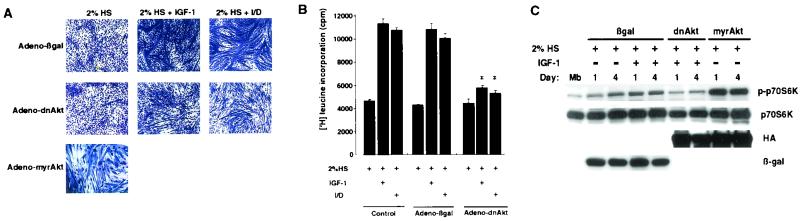

Previous studies showed that plasmids expressing constitutively active or dominant-negative Akt constructs will produce increases or decreases in the measured widths of individually transfected myotubes (6, 52), suggesting that the Akt signaling step controls fiber hypertrophy. For the present study, we used adenovirus vectors expressing Akt constructs because they transduce skeletal muscle cells at a very high frequency (>90%), permitting biochemical analyses of the differentiating cultures under a variety of growth conditions. To assess the usefulness of these reagents in this system, transduction-dependent alterations in the morphology of differentiating myotubes in the presence or absence of hypertrophic agents were examined. The inclusion of IGF-I or I/D in the differentiation medium led to visibly larger myotubes by 4 days in control cultures transduced with Adeno-βgal (Fig. 2A). No detectable differences in myotube morphology were observed between mock- and Adeno-βgal-infected cultures (unpublished data). Transduction with Adeno-dnAkt reduced the hypertrophic phenotype that was induced by incubation with IGF-I or I/D. Under the conditions of these assays, Adeno-dnAkt had little or no effect on the differentiation of cultures in differentiation medium alone. Conversely, transduction with Adeno-myrAkt promoted the formation of visibly thicker myotubes in the absence of hypertrophic stimuli.

FIG. 2.

Effects of IGF-I and I/D on hypertrophy and p70S6 kinase phosphorylation. (A) Morphological analysis of Akt-mediated hypertrophy. C2C12 cells were cultured in growth medium and changed to differentiation medium. After 12 h, cells were infected for 12 h with Adeno-βgal, Adeno-dnAkt, or Adeno-myrAkt at an MOI of 250. The medium was replaced with medium containing either 2% horse serum (HS), 2% horse serum with IGF-I, or 2% horse serum with I/D. Microscopic analysis of cultures was performed at day 4 postdifferentiation. Cells were fixed and stained with 5% Giemsa stain. All microscopic fields are shown at the same magnification. (B) Akt signaling is essential for hypertrophy-associated protein synthesis. C2C12 cultures were infected with Adeno-dnAkt or Adeno-βgal or mock infected (control) as described for panel A. [3H]leucine incorporation was determined as described in Materials and Methods between days 3 and 4 in differentiation medium. Values are means and standard errors of the means for three independent experiments performed in triplicate. An asterisk indicates a P value of <0.01 for a comparison with cells that were mock infected or infected with Adeno-βgal under identical culture conditions. (C) C2C12 cells were cultured as described in panel A and changed to differentiation medium. After 12 h, cells were infected for 12 h with Adeno-βgal, Adeno-dnAkt, or Adeno-myrAkt at an MOI of 250. The medium was replaced with medium containing either 2% horse serum or 2% horse serum with IGF-I. Western immunoblot analysis was performed by using anti-phospho-p70S6 kinase (p-p70S6K), anti-p70S6 kinase (p70S6K), anti-HA (HA), and anti-β-galactosidase (β-gal) antibodies on the indicated days postdifferentiation. Mb, myoblasts.

Quantitative analyses of the effects of Adeno-dnAkt on I/D- and IGF-I-induced hypertrophy were performed by measuring [3H]leucine incorporation into protein (Fig. 2B). Treatment with either IGF-I or I/D increased leucine incorporation into protein by a factor of 2 in differentiating cultures of myocytes. To test whether Akt signaling is essential for this induction of protein synthesis, differentiating cultures were transduced with Adeno-dnAkt prior to growth factor stimulation. Adeno-dnAkt inhibited IGF-I- and I/D-induced leucine incorporation by approximately 90%, whereas transduction with Adeno-βgal had no effect on the hypertrophic response (Fig. 2B). The effect of Adeno-dnAkt on IGF-I- and I/D-stimulated leucine incorporation was dose dependent, with the maximal effect being observed at an Adeno-dnAkt MOI of 250 (unpublished data). Adeno-dnAkt had no effect on DNA synthesis, as determined by measuring [3H]thymidine incorporation (unpublished data), indicating that Akt signaling is essential for IGF-I- and I/D-induced hypertrophy, with little or no effect on myocyte hyperplasia.

Insulin and other growth factors control protein synthesis, at least in part, through the activation of p70S6 kinase (48, 59). Incubation of cultures for 1 or 4 days in differentiation medium in the presence of IGF-I led to an increase in p70S6 kinase phosphorylation compared with that seen in myoblast cultures incubated in differentiation medium for 30 min (Fig. 2C). Transduction with Adeno-dnAkt decreased p70S6 kinase phosphorylation, whereas transduction with Adeno-myrAkt led to a marked increase in p70S6 kinase phosphorylation. These data suggest that p70S6 kinase functions downstream of Akt signaling to control protein synthesis in differentiating muscles.

LDH activity and intracellular lactate also represent biochemical markers of myocyte hypertrophy (58). Both IGF-I and I/D treatments increased LDH activity approximately threefold in differentiating C2C12 cultures (Table 1). When these cultures were transduced with Adeno-dnAkt, the I/D- and IGF-I-induced increase in LDH activity was significantly inhibited. Transduction with Adeno-dnAkt had no effect on basal LDH activity in cells cultured in differentiation medium alone. A similar pattern of regulation was observed with intracellular lactate (Table 1). Infection of cultures with Adeno-βgal had no detectable effect on LDH activity or lactate levels under any experimental conditions. Collectively, these data suggest that manipulation of Akt signaling with adenovirus vectors will modulate biochemical markers of myotube hypertrophy, including the induction of protein translation and metabolic alterations.

TABLE 1.

Akt signaling is essential for hypertrophy-induced LDH activity and lactate levelsa

| Vector | Medium conditions | LDH activity (Berger-Broida U/mg) | Lactate level (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 2% HS | 594 ± 119 | 5.1 ± 0.4 |

| 2% HS + IGF-I | 1,728 ± 17 | 31.0 ± 1.4 | |

| 2% HS + I/D | 1,772 ± 10 | 24.1 ± 1.3 | |

| Adeno-βgal | 2% HS | 581.5 ± 120.4 | 4.2 ± 0.2 |

| 2% HS + IGF-I | 1,733.3 ± 9.1 | 30.8 ± 1.1 | |

| 2% HS + I/D | 1,800.2 ± 16.0 | 23.1 ± 2.1 | |

| Adeno-dnAkt | 2% HS | 534.9 ± 68.8 | 3.92 ± 0.2 |

| 2% HS + IGF-I | 1,054.7 ± 103.5b | 10.1 ± 0.4b | |

| 2% HS + I/D | 1,025.1 ± 53.5b | 10.7 ± 0.3b |

C2C12 cells were cultured and infected with adenovirus vectors at an MOI of 250 as described in the legend to Fig. 2. At day 4 postdifferentiation, LDH activity and lactate levels were measured as described in Materials and Methods. The values shown represent the mean and standard error of the mean for triplicate experiments.

The P value for a comparison with differentiation medium was <0.05.

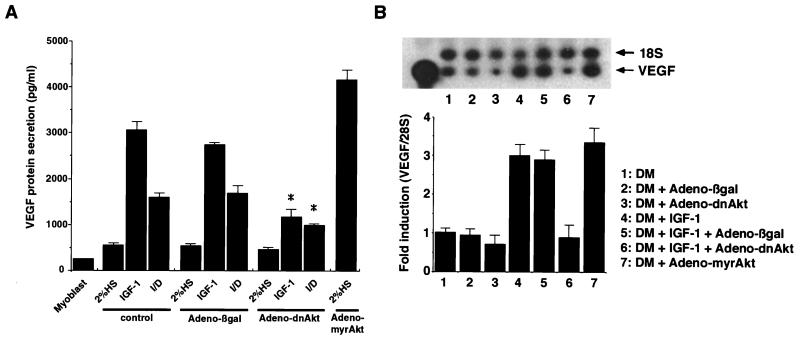

Hypertrophy-associated VEGF regulation in vitro.

Because physiological hypertrophy is temporally coupled to the induction of angiogenesis (47), VEGF production during myocyte differentiation and hypertrophy was examined. During C2C12 myoblast differentiation, the VEGF concentration increased 2.3-fold in the culture supernatant relative to that in myoblasts cultured in growth medium (Fig. 3A). In contrast, treatment with the hypertrophic agents IGF-I and I/D increased the amount of secreted VEGF by 12.8- and 6.7-fold, respectively, relative to that in myoblasts in growth medium. Transduction with Adeno-dnAkt significantly inhibited I/D- and IGF-I-induced VEGF secretion but had little or no effect on the basal VEGF production observed in differentiation medium alone. Conversely, transduction with Adeno-myrAkt led to robust VEGF secretion from cells maintained in differentiation medium. Infection with the control vector Adeno-βgal had no effect on VEGF secretion under any of these conditions. Collectively, these data show that Akt signaling is both essential and sufficient for hypertrophy-associated VEGF synthesis by skeletal muscle in vitro.

FIG. 3.

Akt signaling regulates VEGF synthesis and secretion upon myocyte hypertrophy. (A) C2C12 myoblasts were seeded on 24-well plates and cultured in growth medium. Subconfluent cultures were exposed to differentiation medium. After 12 h, cells were infected with the indicated adenovirus vectors (MOI, 250) or mock infected (control). After 12 h, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing either 2% horse serum (HS), 2% horse serum with IGF-I, or 2% horse serum with I/D. The medium was changed every day, and on day 4 postdifferentiation, 50 μl of medium was assayed for VEGF concentrations as described in Materials and Methods. Values are means and standard errors for three independent experiments performed in triplicate. An asterisk indicates a P value of <0.01 for a comparison with Adeno-βgal or control results under identical culture conditions. (B) Regulation of VEGF transcript levels by Akt signaling. RNA isolation and RT-PCR analysis were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Equal amounts of RT-PCR products were loaded and analyzed on a 6% acrylamide-8 M urea gel. Data are representative of three separate experiments; data are means ± standard errors of the mean. Lane 1 was loaded with amplified Vegf DNA and used as a positive control. 18S rRNA was used as an endogenous standard. The image was captured electronically, and the bands were quantified by using image analysis software (NIH Image). The degree of mRNA induction was determined as the value relative to that for 2% horse serum-stimulated cells (lane 1). DM, differentiation medium.

Akt-induced VEGF secretion in various cultured human cell lines was also evaluated (Table 2). Consistent with the findings obtained for the murine C2C12 cell line, transduction with Adeno-myrAkt promoted VEGF secretion in human skeletal muscle cells, human coronary artery smooth muscle cells, and HeLa cells. In human skeletal muscle and HeLa cells, the level of induction of VEGF achieved by Adeno-myrAkt was comparable to the level of induction achieved by hypoxia.

TABLE 2.

Relative induction of VEGF in different human cell typesa

| Treatment | Relative VEGF expression in the following cells:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa | HSKM | HSM | |

| Nonhypoxic, no virus | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Nonhypoxic, Adeno-βgal | 0.95 ± 0.19 | 1.12 ± 0.15 | 0.91 ± 0.15 |

| Nonhypoxic, Adeno-myrAkt | 3.27 ± 0.31b | 3.88 ± 0.34b | 3.12 ± 0.29b |

| Hypoxic, no virus | 3.57 ± 0.46b | 5.43 ± 0.67b | ND |

Cells were infected with adenovirus vectors or exposed to hypoxia for 48 h prior to the determination of VEGF levels in the medium by ELISAs. Data are representative of three or four independent experiments and are expressed as mean and standard error of the mean relative to basal VEGF production under mock-infected, nonhpoxic conditions. HSKM, human skeletal muscle; HSM, human smooth muscle; ND, not determined.

The P value for a comparison with the control (nonhypoxic, no virus) was <0.05.

Vegf mRNA levels were examined to assess the mechanism of Akt-mediated VEGF regulation during myocyte hypertrophy. As shown in Fig. 3B, incubation with IGF-I increased the amounts of Vegf mRNA in C2C12 cells by threefold over that in cells in differentiation medium alone (n = 3; P < 0.05). Transduction with Adeno-dnAkt inhibited the IGF-I-stimulated increase in Vegf transcript levels (0.9- ± 0.32-fold relative to the level in differentiation medium alone; the P value was <0.05 for a comparison with the level obtained with differentiation medium plus IGF-I) but had little or no effect on basal Vegf transcript levels. Infection with the control vector Adeno-βgal had no effect on basal or IGF-I-regulated Vegf expression. In contrast, infection with Adeno-myrAkt induced Vegf mRNA expression in cells cultured in differentiation medium with no IGF-I (3.3- ± 0.39-fold; the P value was <0.05 for a comparison with the level obtained with differentiation medium plus Adeno-βgal). Thus, the IGF-I- or Akt-mediated regulation of Vegf mRNA parallels the changes in VEGF protein expression. RNase protection analyses of cultured human skeletal muscle cells also detected the induction of VEGF-A but not VEGF-C or Ang-1 transcripts following transduction with Adeno-myrAkt (data not shown).

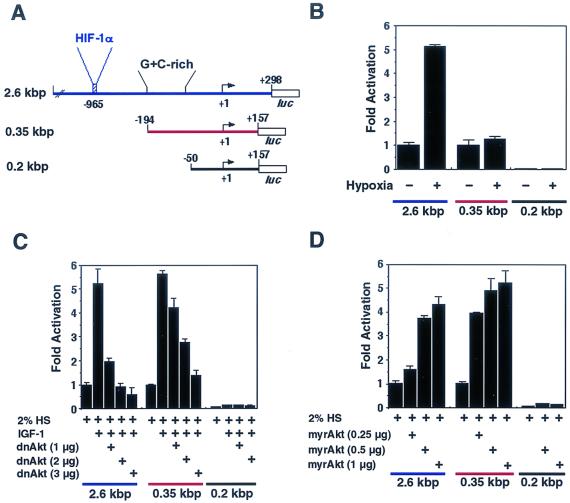

To test whether the IGF-I- or Akt-regulated expression of VEGF occurs at the level of transcription, the activities of a series of VEGF promoter constructs in transiently transfected C2C12 cells were assessed. Constructs contained various lengths of the 5′-flanking sequences from the human VEGF gene upstream of the luciferase reporter gene (Fig. 4A). The 2.6-kbp promoter construct (−2361 to +298), containing the hypoxic regulatory element (position −965), was induced fivefold by hypoxia in C2C12 cells cultured in differentiation medium (Fig. 4B). The shorter, 0.35-kbp fragment lacking the HIF-1α binding site was not responsive to regulation by hypoxia, and the 0.2-kbp fragment was essentially inactive. In contrast to the response to hypoxia, the 2.6- and 0.35-kbp Vegf promoter fragments were similarly activated by IGF-I in differentiating muscle cultures (Fig. 4C). Depending upon specific cell culture and transfection conditions, the activation of these promoter fragments by IGF-I ranged from two- to sixfold (data not shown). Cotransfection with a dominant-negative Akt expression plasmid led to a dose-dependent reduction in IGF-I-activated transcription from the Vegf promoter fragments (Fig. 4C). Conversely, cotransfection with a constitutively active Akt expression plasmid led to a dose-dependent increase in promoter activity from both 2.6- and 0.35-kbp fragments (Fig. 4D). Collectively, these results show that IGF-I- or Akt-mediated regulation of VEGF synthesis occurs, at least in part, at the level of transcription and that hypoxia and IGF-I or Akt activate Vegf transcription through distinct DNA regulatory elements in the promoter.

FIG. 4.

Hypertrophy-associated VEGF transcription requires Akt signaling but is independent of HIF-1α. (A) Diagram of VEGF promoter-luciferase reporter constructs. The HIF-1α binding site is located 965 bp upstream from the start of transcription and is present only on the 2.6-kbp promoter construct. (B) Hypoxia activates the 2.6-kbp promoter fragment but not the 0.35- or 0.2-kbp promoter fragment. C2C12 cells were transfected with 2 μg of the indicated VEGF promoter-luciferase reporter constructs. After 36 h, cells were exposed to hypoxia or remained under aerobic conditions for another 12 h. Luciferase activity in lysates is expressed relative to the activity of the 2.6-kbp construct under nonhypoxic conditions. (C) Akt is essential for the induction of VEGF promoter activity by IGF-I. The indicated VEGF promoter-luciferase reporter constructs were cotransfected with increasing amounts of Adeno-dnAkt in C2C12 cells cultured in differentiation medium. Cultures were incubated with or without IGF-I for 48 h. Cells were harvested for luciferase measurements, and the degree of IGF-I induction for each test plasmid is expressed relative to that for the 2.6-kbp VEGF promoter-reporter construct alone. HS, horse serum. (D) Adeno-myrAkt activates the VEGF promoter independently of the hypoxia-inducible element. The indicated VEGF promoter-luciferase reporter constructs were cotransfected with increasing amounts of Adeno-myrAkt in C2C12 cells cultured in differentiation medium. Cells were harvested for luciferase assays 48 h after transfection, and the degree of induction by Adeno-myrAkt is expressed relative to that for the 2.6-kbp VEGF promoter-luciferase construct alone. Data in panels B to D are presented as means ± standard errors of the mean for three experiments.

Akt signaling promotes myofiber hypertrophy and VEGF synthesis in vivo.

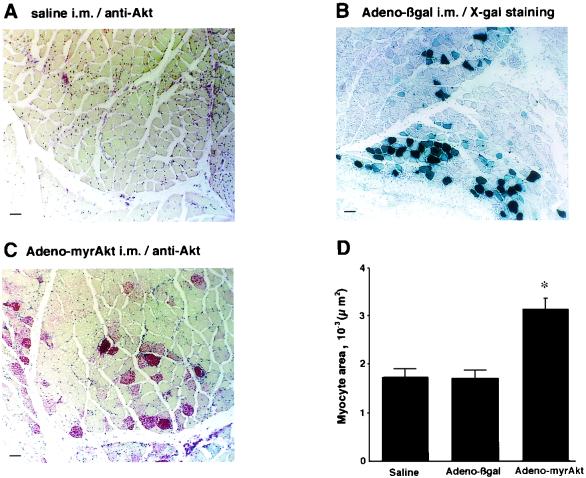

To investigate whether myogenic Akt signaling is sufficient to promote fiber growth and angiogenesis in vivo, the gastrocnemius muscle of mice was injected with saline, Adeno-βgal, or Adeno-myrAkt. Figure 5 shows representative histological sections of the injected muscle stained with anti-Akt1 antibody (red) or X-Gal to detect β-galactosidase activity (blue). In saline-injected muscle, Akt protein expression was faint or undetectable under these assay conditions (Fig. 5A). However, positive red myofibers were readily apparent in the muscle injected with Adeno-myrAkt at a frequency that was comparable to that of X-Gal-positive fibers in the muscle injected with Adeno-βgal (compare Fig. 5B and C). The cross-sectional area of 100 myofibers selected at random from multiple animals was determined for each experimental group. The red-staining fibers in the muscle injected with Adeno-myrAkt exhibited a 1.7-fold-greater diameter than the blue-staining cells in the Adeno-βgal-injected muscle (Fig. 5D). The diameter of β-galactosidase-positive fibers was not significantly different from that of fibers in saline-injected gastrocnemius muscle.

FIG. 5.

Intramuscular transfection of Adeno-myrAkt is sufficient to induce myofiber hypertrophy in gastrocnemius muscle. The right gastrocnemius muscle of C57BL/6 mice was injected with 100 μl of saline alone (A), Adeno-βgal (B), or Adeno-myrAkt (C). Immunostaining for Akt (A and C, red reaction product) and X-Gal staining (B, blue reaction product) were performed at 14 days after transduction. i.m., intramuscular. Bars, 50 μm. (D) Quantitative analysis of myofiber cross-sectional area. A total of 100 myocytes were analyzed from each of six mice per experimental condition. Myofibers were selected at random for analysis in the saline-injected limbs, blue-stained myofibers were analyzed for the Adeno-βgal-injected limbs, and red-stained fibers were analyzed for the Adeno-myrAkt-injected limbs. The average myocyte area for each condition is expressed relative to the value for myocytes from the saline-injected limb. Values are means and standard deviations. An asterisk indicates a P value of <0.05 for a comparison with Adeno-βgal or saline.

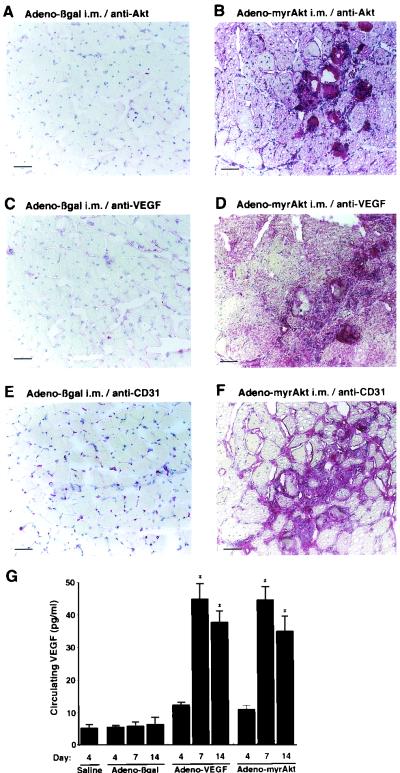

Immunohistochemical analyses were performed to analyze VEGF production within the injected portions of the gastrocnemius muscle (Fig. 6). In Adeno-myrAkt-injected muscle, an enhanced signal for VEGF was found in sections adjacent to those that stained positive for increased Akt expression (Fig. 6B and D). The Adeno-myrAkt-injected muscle segments exhibiting the most robust Akt and VEGF expression also displayed a disorganized network of CD31-positive endothelial cells in adjacent sections (Fig. 6F). This pattern of CD31 staining is reminiscent of the focal vascular structures that are reported to occur from excessive VEGF overexpression (31, 56, 63), and these data provided preliminary evidence to suggest that increases in myogenic Akt signaling can promote blood vessel growth.

FIG. 6.

Injection of Adeno-myrAkt into mouse skeletal muscle increases tissue-resident and circulating VEGF levels and produces a disorganized pattern of CD31-positive cells at sites of locally high VEGF expression. Transverse cryosections of mouse gastrocnemius muscle from the Adeno-βgal-treated (A, C, and E) and Adeno-myrAkt-treated (B, D, and F) groups were immunostained for Akt (A and B), VEGF (C and D), and CD31-positive cells (E and F). Bars, 50 μM. Control muscle sections injected with Adeno-βgal showed faint staining for Akt and VEGF proteins and a normal distribution of CD31-positive cells. In contrast, sections of Adeno-myrAkt-injected muscle showing intense immunostaining for Akt and VEGF displayed a disorganized network of CD31-positive cells. i.m., intramuscular. (G) Intramuscular injection of Adeno-VEGF or Adeno-myrAkt increases serum VEGF levels. The right gastrocnemius muscle of C57BL/6 mice was injected with 100 μl of saline or Adeno-βgal, Adeno-myrAkt, or Adeno-VEGF. Adeno-VEGF expresses the murine VEGF165 protein from the cytomegalovirus promoter. At 4, 7, and 14 days after injection, 50 μl of serum was collected, and VEGF levels were measured by ELISAs. Values are expressed as means and standard deviations. An asterisk indicates a P value of <0.01 for a comparison with Adeno-βgal for each time point. There were six mice for each time point and condition.

To test whether myogenic Akt signaling can increase circulating levels of VEGF, serum VEGF levels were determined by immunoassays at 4, 7, and 14 days after the injection of adenovirus constructs into mouse gastrocnemius muscle (Fig. 6G). Intramuscular injection of Adeno-myrAkt led to a time-dependent increase in circulating VEGF to levels comparable to those obtained from the injection of Adeno-VEGF, whereas injection with Adeno-βgal did not detectably affect VEGF levels. Because the intramuscular injection of adenovirus vectors leads to transgene expression that is predominantly localized to myofibers (Fig. 5B and C), the source of the circulating VEGF is likely to be myogenic cells, although contributions of nonmyogenic cells cannot be excluded. In contrast, the injection of Adeno-myrAkt, Adeno-VEGF, or Adeno-βgal had no detectable effects on the circulating levels of bovine fibroblast growth factor or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (data not shown).

Increased myogenic Akt signaling promotes angiogenesis in ischemic tissue.

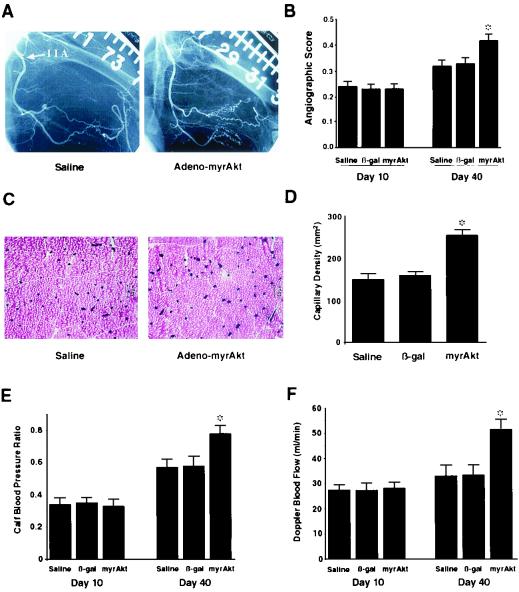

A preclinical model of vascular insufficiency was evaluated to test whether an increase in myogenic Akt signaling in muscle is sufficient to promote functional angiogenesis. In this model, unilateral resection of the femoral artery and major side branches is performed (49). As a result of the surgery, the internal iliac artery is the remaining major conduit of blood flow, and there is a marked decrease in limb perfusion. At 10 days after surgery to allow recovery and establish a baseline, rabbits were divided into three experimental groups, and intramuscular injections of saline, Adeno-βgal, or Adeno-myrAkt were administered. Angiogenic assessment at 40 days after surgery revealed more collateral vessels with characteristic corkscrew morphology in the Adeno-myrAkt-treated animals than in control animals (Fig. 7A). The enhanced collateral vessel formation was reflected by a statistically significant increase in the angiographic score at 40 days postsurgery but not at 10 days, when the injections were performed (Fig. 7B). Treatment with Adeno-myrAkt also increased capillary density in the adductor muscle of the ischemic limb (Fig. 7C). This increase was statistically significant compared with the results for saline- or Adeno-βgal-treated animals (Fig. 7D).

FIG. 7.

Intramuscular injection of Adeno-myrAkt promotes blood vessel formation in the rabbit hind limb. Rabbits underwent unilateral resection of the femoral artery and its major side branches. After 10 days to allow recovery and establish a baseline, rabbits were randomized to receive intramuscular injections of saline, Adeno-βgal, or Adeno-myrAkt in the ischemic limb. (A) Internal iliac artery angiography was performed at 40 days after femoral artery resection to assess collateral vessel formation. (B) Quantitative analysis of collateral vessel growth between 10 and 40 days postresection in the different treatment groups. (C) Rabbits were sacrificed at 40 days, and alkaline phosphatase staining of adductor muscles from the ischemic limbs was performed to assess capillary density. (D) Quantitative analysis of capillary density reveals a higher capillary density in the adductor muscles excised from ischemic limbs that received an intramuscular injection of Adeno-myrAkt. (E) The calf blood pressure ratio was calculated as the systolic pressure of the surgically treated limb divided by that of the normal limb for each rabbit. (F) Blood flow in the internal iliac artery of the affected limb was analyzed by Doppler guide wire measurements on days 10 and 40 under conditions of maximal blood flow. Intramuscular injections were performed at day 10 after the measurements. Data in panels B, D, E, and F are presented as means and standard errors of the means (six rabbits for each treatment group). An asterisk indicates a P value of <0.05 for a comparison with ischemic limbs receiving intramuscular injections of saline or Adeno-βgal, as determined by analysis of variance.

To assess the physiological consequences of these anatomic changes in collateral and capillary vessels, the ratios of calf systolic pressures between the normal and test limbs were analyzed (Fig. 7E). The calf blood pressure ratio was statistically higher in the Adeno-myrAkt-treated group than in the control group, consistent with an increase in limb perfusion. Direct evidence for an increase in limb perfusion in the Adeno-myrAkt-treated group was provided by measurement of blood flow through the internal iliac artery of the test limb by use of a Doppler guide wire (Fig. 7F). To ascertain blood flow, vessel diameter was determined angiographically, and average peak velocity through the internal iliac artery was determined under conditions of maximal flow. When the 10-day and 40-day follow-up values were compared, there was a statistically significant improvement in flow in the limb treated with Adeno-myrAkt as opposed to saline or Adeno-βgal.

DISCUSSION

During postnatal muscle growth, capillary formation accompanies myofiber hypertrophy to ensure adequate nutrient and oxygen supply for normal muscle function during contraction (32). While studies have shown that Akt signaling is a key regulator of cell and tissue growth in Drosophila (71) and mammals (9), its role in vascularization during tissue growth is incompletely understood. It was previously reported that Akt1 and its structurally similar homolog, Akt2, are upregulated during myogenic differentiation (2, 3, 21). Activation of Akt signaling in skeletal muscle has been shown to be crucial for the suppression of apoptosis during differentiation (21, 36) and the control of myofiber size (6, 51, 52). Here, we analyzed the role of myogenic Akt signaling in coordinating blood vessel recruitment with myofiber hypertrophy, an essential feature of normal muscle maturation.

It is well established that IGF and I/D promote skeletal muscle hypertrophy (4, 43, 58). Here, we reported that VEGF protein secretion is modestly induced (2.3-fold) upon C2C12 cell differentiation in low-mitogenicity medium, consistent with a previous report that examined Vegf transcript expression (11), while incubation with IGF and I/D had more profound effects on VEGF secretion into the culture medium (6.7- to 12.8-fold induction relative to the results for myoblasts). Transduction with Adeno-dnAkt inhibited the hypertrophy-associated induction of VEGF but did not interfere with basal VEGF expression under the conditions of these assays. Transduction with Adeno-dnAkt also inhibited the hypertrophic action of these agents in cultured C2C12 cells, as determined by microscopic observations of myofiber size, measurements of [3H]leucine incorporation into protein, and the induction of LDH activity and lactate production. Conversely, transduction with Adeno-myrAkt promoted fiber hypertrophy and induced high levels of VEGF secretion in cells cultured in normal differentiation medium in the absence of IGF-I or I/D stimulation. Taken together, these data show that Akt signaling is essential and sufficient for both myofiber hypertrophy and angiogenic growth factor secretion. Therefore, this regulatory pathway may function to maintain capillary density as organ size varies during postnatal development and can account for the temporal coupling of blood vessel recruitment and myofiber growth which has been observed in animal models of compensatory hypertrophy (47).

Here, we showed that hypertrophic agents regulated Vegf mRNA levels and promoter activity in an Akt-dependent manner. Previous studies showed that the PI 3-kinase/Akt-mediated regulation of HIF-1α expression is required for Vegf transcription in Ha-ras-transformed cells (39) and glioblastoma-derived cell lines (73). In contrast, the findings of this study show that promoter fragments containing the hypoxia regulatory element were largely dispensable for the Akt-mediated regulation of Vegf transcription and that different DNA regulatory sequences confer hypertrophy-inducible expression in C2C12 cells. In other experiments, transduction with Adeno-dnAkt had no effect on the induction of HIF-1α by hypoxia, nor did Adeno-myrAkt induce HIF-1α under nonhypoxic conditions in cultured skeletal or cardiac muscle (unpublished data). Collectively, these data suggest that distinct regulatory mechanisms control VEGF synthesis and blood vessel recruitment during normal tissue development and in response to pathological stimuli, such as ischemic stress and tumorigenesis. Presumably, the hypoxic conditions generated by robust tumor growth or acute blood vessel occlusion promote Vegf transcription via a mechanism that requires both Akt and HIF-1α, whereas normal postnatal tissue growth appears to involve Akt-mediated regulation of Vegf transcription that is independent of HIF-1α. Consistent with this notion, it has been reported that targeted deletion of the hypoxia response element in the Vegf promoter leads to structurally normal muscle in mice, although they suffer from late-onset motor neuron degeneration (44). Given that deletion of a single allele of Vegf is lethal (7), it appears likely that Vegf regulation during normal tissue growth involves regulatory mechanisms that are largely independent of HIF-1α.

Transient transfection experiments revealed that a G+C-rich region between positions −194 and −50 relative to the start of transcription in the Vegf promoter is essential for activation by hypertrophic agents in muscle. Proteins that bind to this region include SP1, SP3, and AP2 (25, 54, 65). Although the regulation of these sequences by mitogen-activated protein kinase was described previously (41, 66), the data presented here are the first to show that Akt signaling can regulate transcription through this element. Interestingly, it was recently reported that protein kinase C zeta also controls VEGF transcription by acting upon this element (45). Protein kinase C zeta is regulated by PI 3-kinase (10, 38) and in some circumstances can function as an upstream regulator of Akt (17).

This study also provides evidence in animal models to support the hypothesis that Akt signaling couples VEGF synthesis with myofiber hypertrophy. Injection of Adeno-myrAkt into normal mouse gastrocnemius muscle was found to increase myofiber cross-sectional area, and these fibers exhibited increased immunostaining for VEGF protein. Muscle segments exhibiting the highest Akt transgene product signal in myofibers also displayed a disorganized network of CD31-positive endothelial cells. These structures appeared morphologically similar to the focal vascular structures that form when VEGF is overexpressed from plasmids or transplanted allogeneic cells (37, 56, 63). These results provide preliminary evidence that an increase in myogenic Akt signaling can promote capillary vessel growth in vivo and are consistent with the finding that retrovirus vectors expressing constitutively active constructs of PI 3-kinase or Akt can induce hemangiosarcomas in chicken embryo chorioallantoic membranes (33). Our study also found that the intramuscular injection of Adeno-myrAkt produced a time-dependent increase in the circulating levels of VEGF. Of particular note, Akt-induced VEGF production was similar in time course and magnitude to that resulting from the intramuscular injection of Adeno-VEGF, indicating the efficiency at which Akt can activate VEGF production in vivo.

A rabbit hind limb model of vascular insufficiency was used to assess whether myogenic Akt signaling can promote the recruitment of functional blood vessels. Intramuscular administration of Adeno-myrAkt to ischemic limbs resulted in the formation of more angiographically detectable collateral vessels and an increase in capillary density in adductor muscle relative to the results obtained for controls. These limbs also displayed improved hemodynamic properties, as determined by measurements of blood flow through the internal iliac artery and limb blood pressure. Because this rabbit hind limb model of vascular insufficiency has been used to document the efficacy of proangiogenic agents prior to clinical trials in patients (5, 31), the findings reported here suggest that activation of myogenic Akt signaling could have utility for therapeutic angiogenesis in patients with ischemic tissue diseases. Strategies being considered for therapeutic angiogenesis include the manipulation of individual growth factors (35) or transcriptional regulators of growth factor synthesis (72), whereas perturbation of proangiogenic signaling pathways has not been explored previously. In this regard, agents that promote myogenic Akt signaling may be advantageous to a single growth factor protein or gene because of their potential ability to promote myofiber hypertrophy in addition to angiogenesis, a scenario that may be desirable in peripheral artery disease patients, who often experience severe muscular atrophy (50). Further benefits may derive from the action of Akt in enhancing myocyte survival (21, 23, 36, 40) and diminishing cellular stress in ischemic muscle by promoting glucose oxidation (12, 16). Thus, myogenic Akt signaling may serve as a potential target for drugs to treat vascular insufficiency and the sequelae associated with chronic ischemia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants HD-23681, HL-50692, AR-40197, AG-15052, and AG-17241.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alessi, D. R., M. Andjelkovic, B. Caudwell, P. Cron, N. Morrice, P. Cohen, and B. A. Hemmings. 1996. Mechanism of activation of protein kinase B by insulin and IGF-1. EMBO J. 15:6541-6551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altomare, D. A., K. Guo, J. Q. Cheng, G. Sonoda, K. Walsh, and J. R. Testa. 1995. Cloning, chromosomal localization and expression analysis of the mouse Akt2 oncogene. Oncogene 11:1055-1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altomare, D. A., G. E. Lyons, Y. Mitsuuchi, J. Q. Cheng, and J. R. Testa. 1998. Akt2 mRNA is highly expressed in embryonic brown fat and AKT2 kinase is activated by insulin. Oncogene 16:2407-2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barton-Davis, E. R., D. I. Shoturma, A. Musaro, N. Rosenthal, and H. L. Sweeney. 1998. Viral mediated expression of insulin-like growth factor I blocks the aging-related loss of skeletal muscle function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:15603-15607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumgartner, I., A. Pieczek, O. Manor, R. Blair, M. Kearney, K. Walsh, and J. M. Isner. 1998. Constitutive expression of phVEGF165 after intramuscular gene transfer promotes collateral vessel development in patients with critical limb ischemia. Circulation 97:1114-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bodine, S. C., T. N. Stitt, M. Gonzalez, W. O. Kline, G. L. Stover, R. Bauerlein, E. Zlotchenko, A. Scrimgeour, J. C. Lawrence, D. J. Glass, and G. D. Yancopoulos. 2001. Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:1014-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmeliet, P., V. Ferreira, G. Breier, S. Pollefeyt, L. Kieckens, M. Gertsenstein, M. Fahrig, A. Vandenhoeck, K. Harpal, C. Eberhardt, C. Declercq, J. Pawling, L. Moons, D. Collen, W. Risau, and A. Nagy. 1996. Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature 380:435-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpenter, S., and G. Karpati. 1982. Necrosis of capillaries in denervation atrophy of human skeletal muscle. Muscle Nerve 5:250-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, W. S., P. Z. Xu, K. Gottlob, M. L. Chen, K. Sokol, T. Shiyanova, I. Roninson, W. Weng, R. Suzuki, K. Tobe, T. Kadowaki, and N. Hay. 2001. Growth retardation and increased apoptosis in mice with homozygous disruption of the Akt1 gene. Genes Dev. 15:2203-2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou, M. M., W. Hou, J. Johnson, L. K. Graham, M. H. Lee, C. S. Chen, A. C. Newton, B. S. Schaffhausen, and A. Toker. 1998. Regulation of protein kinase C zeta by PI 3-kinase and PDK-1. Curr. Biol. 8:1069-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Claffey, K. P., W. O. Wilkison, and B. M. Spiegelman. 1992. Vascular endothelial growth factor. Regulation by cell differentiation and activated second messenger pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 267:16317-16322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai, Y., E. M. Schwarz, D. Gu, W.-W. Zhang, N. Sarvetnick, and I. M. Verma. 1995. Cellular and humoral immune responses to adenoviral vectors containing factor IX gene: tolerization of factor IX and vector antigens allows for long-term expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1401-1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Datta, S. R., A. Brunet, and M. E. Greenberg. 1999. Cellular survival: a play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 13:2905-2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Degens, H., Z. Turek, L. J. C. Hoofd, M. A. Van't Hof, and R. A. Binkhorst. 1992. The relationship between capillarisation and fibre types during compensatory hypertrophy of the plantaris muscle in the rat. J. Anat. 180:455-463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Degens, H., J. H. Veerkamp, H. T. B. van Moerkerk, Z. Turek, L. J. C. Hoofd, and R. A. Binkhorst. 1993. Metabolic capacity, fibre type area and capillarization of rat plantaris muscle. Effects of age, overload and training and relationship with fatigue resistance. Int. J. Biochem. 25:1141-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diaz, R., E. A. Paolasso, L. S. Piegas, C. D. Tajer, M. G. Moreno, R. Corvalan, J. E. Isea, G. Romero, et al. 1998. Metabolic modulation of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 98:2227-2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doornbos, R. P., M. Theelen, P. C. van der Hoeven, W. J. van Blitterswijk, A. J. Verkleij, and P. M. van Bergen en Henegouwen. 1999. Protein kinase Czeta is a negative regulator of protein kinase B activity. J. Biol. Chem. 274:8589-8596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrara, N. 1999. Molecular and biological properties of vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Mol. Med. 77:527-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Florini, J. R., K. A. Magri, D. Z. Ewton, P. L. James, K. Grindstaff, and P. S. Rotwein. 1991. “Spontaneous” differentiation of skeletal myoblasts is dependent upon autocrine secretion of insulin-like growth factor-II. J. Biol. Chem. 266:15917-15923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franzini-Armstrong, C., and D. A. Fischman. 1994. Morphogenesis of skeletal muscle fibers, p. 74-96. In A. G. Engel and C. Franzini-Armstrong (ed.), Myology: basic and clinical, 2nd ed., vol. 1. McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc., New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujio, Y., K. Guo, T. Mano, Y. Mitsuuchi, J. R. Testa, and K. Walsh. 1999. Cell cycle withdrawal promotes myogenic induction of Akt, a positive modulator of myocyte survival. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:5073-5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujio, Y., Y. Mitsuuchi, J. R. Testa, and K. Walsh. 2001. Activation of Akt2 inhibits anoikis and apoptosis induced by myogenic differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 8:1207-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujio, Y., T. Nguyen, D. Wencker, R. N. Kitsis, and K. Walsh. 2000. Akt promotes survival of cardiomyocytes in vitro and protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury in mouse heart. Circulation 101:660-667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujio, Y., and K. Walsh. 1999. Akt mediates cytoprotection of endothelial cells by vascular endothelial growth factor in an anchorage-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 274:16349-16354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gille, J., R. A. Swerlick, and S. W. Caughman. 1997. Transforming growth factor-alpha-induced transcriptional activation of the vascular permeability factor (VPF/VEGF) gene requires AP-2-dependent DNA binding and transactivation. EMBO J. 16:750-759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han, V. K. M., A. J. D'Ercole, and P. K. Lund. 1987. Cellular localization of somatomedin (insulin-like growth factor) messenger RNA in the human fetus. Science 236:193-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hixon, M. L., C. Muro-Cacho, M. W. Wagner, C. Obejero-Paz, E. Millie, Y. Fujio, Y. Kureishi, T. Hassold, K. Walsh, and A. Gualberto. 2000. Akt1/PKB upregulation leads to vascular smooth muscle cell hypertrophy and polyploidization. J. Clin. Investig. 106:1011-1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hudlicka, O. 1990. The response of muscle to enhanced and reduced activity, p. 417-439. In J. B. Harris and D. M. Turnbull (ed.), Bailliere's clinical endocrinology and metabolism, vol. 4. Bailliere-Tindal, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ikeda, E., M. G. Achen, G. Breier, and W. Risau. 1995. Hypoxia-induced transcriptional activation and increased mRNA stability of vascular endothelial growth factor in C6 glioma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270:19761-19766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ingjer, F. 1979. Capillary supply and mitochondrial content of different skeletal muscle fiber types in untrained and endurance-trained men. A histochemical and ultrastructural study. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 40:197-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Isner, J. M., A. Pieczek, R. Schainfeld, R. Blair, L. haley, T. Asahara, K. Rosenfield, S. Razvi, K. Walsh, and J. F. Symes. 1996. Clinical evidence of angiogenesis after arterial gene transfer of phVEGF165 in patient with ischaemic limb. Lancet 348:370-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jerusalem, F. 1994. The microcirculation of muscle, p. 361-374. In A. G. Engel and C. Franzini-Armstrong (ed.), Myology: basic and clinical, 2nd ed., vol. 1. McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc., New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang, B. H., J. Z. Zheng, M. Aoki, and P. K. Vogt. 2000. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling mediates angiogenesis and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1749-1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kano, Y., S. Shimegi, K. Masuda, H. Ohmori, and S. Katsuta. 1997. Morphological adaptation of capillary network in compensatory hypertrophied rat plantaris muscle. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 75:97-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laham, R. J., A. Mannam, M. J. Post, and F. Sellke. 2001. Gene transfer to induce angiogenesis in myocardial and limb ischaemia. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 1:985-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawlor, M. A., and P. Rotwein. 2000. Coordinate control of muscle cell survival by distinct insulin-like growth factor activated signaling pathways. J. Cell Biol. 151:1131-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee, R. J., M. L. Springer, W. E. Blanco-Bose, R. Shaw, P. C. Ursell, and H. M. Blau. 2000. VEGF gene delivery to myocardium: deleterious effects of unregulated expression. Circulation 102:898-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Good, J. A., W. H. Ziegler, D. B. Parekh, D. R. Alessi, P. Cohen, and P. J. Parker. 1998. Protein kinase C isotypes controlled by phosphoinositide 3-kinase through the protein kinase PDK1. Science 281:2042-2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mazure, N. M., E. Y. Chen, K. R. Laderoute, and A. J. Giaccia. 1997. Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor by hypoxia is modulated by a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway in Ha-ras-transformed cells through a hypoxia inducible factor-1 transcriptional element. Blood 90:3322-3331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miao, W., Z. Luo, R. N. Kitsis, and K. Walsh. 2000. Intracoronary, adenovirus-mediated Akt gene transfer in heart limits infarct size following ischemia-reperfusion injury in vivo. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 32:2397-2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milanini, J., F. Vinals, J. Pouyssegur, and G. Pages. 1998. p42/p44 MAP kinase module plays a key role in the transcriptional regulation of the vascular endothelial growth factor gene in fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 273:18165-18172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mukhopadhyay, D., B. Knebelmann, H. T. Cohen, S. Ananth, and V. P. Sukhatme. 1997. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene product interacts with Sp1 to repress vascular endothelial growth factor promoter activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:5629-5639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Musarò, A., K. J. A. McCullagh, F. J. Naya, E. N. Olson, and N. Rosenthal. 1999. IGF-1 induces skeletal myocyte hypertrophy through calcineurin in association with GATA-2 and NF-ATc1. Nature 400:581-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oosthuyse, B., L. Moons, E. Storkebaum, H. Beck, D. Nuyens, K. Brusselmans, J. Van Dorpe, P. Hellings, M. Gorselink, S. Heymans, G. Theilmeier, M. Dewerchin, V. Laudenbach, P. Vermylen, H. Raat, T. Acker, V. Vleminckx, L. Van den Bosch, N. Cashman, H. Fujisawa, M. R. Drost, R. Sciot, F. Bruyninckx, D. Hicklin, C. Ince, P. Gressens, F. Lupu, K. H. Plate, W. Robberecht, J. M. Herbert, D. Collen, and P. Carmeliet. 2001. Deletion of the hypoxia-response element in the vascular endothelial growth factor promoter causes motor neuron degeneration. Nat. Genet. 28:131-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pal, S., K. Datta, R. Khosravi-Far, and D. Mukhopadhyay. 2001. Role of protein kinase Czeta in Ras-mediated transcriptional activation of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor expression. J. Biol. Chem. 276:2395-2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pal, S., K. Datta, and D. Mukhopadhyay. 2001. Central role of p53 on regulation of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor (VPF/VEGF) expression in mammary carcinoma. Cancer Res. 61:6952-6957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plyley, M. J., B. J. Olmstead, and E. G. Noble. 1998. Time course of changes in capillarization in hypertrophied rat plantaris muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 84:902-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Proud, C. G., and R. M. Denton. 1997. Molecular mechanisms for the control of translation by insulin. Biochem. J. 328:329-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pu, L. Q., A. D. Sniderman, Z. Arekat, A. M. Graham, R. Brassard, and J. F. Symes. 1993. Angiogenic growth factor and revascularization of the ischemic limb: evaluation in a rabbit model. J. Surg. Res. 54:575-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Regensteiner, J. G., E. E. Wolfel, E. P. Brass, M. R. Carry, S. P. Ringel, M. E. Hargarten, E. R. Stamm, and W. R. Hiatt. 1993. Chronic changes in skeletal muscle histology and function in peripheral arterial disease. Circulation 87:413-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rommel, C., S. C. Bodine, B. A. Clarke, R. Rossman, L. Nunez, T. N. Stitt, G. D. Yancopoulos, and D. J. Glass. 2001. Mediation of IGF-1-induced skeletal myotube hypertrophy by PI(3)K/Akt/mTOR and PI(3)K/Akt/GSK3 pathways. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:1009-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rommel, C., B. A. Clarke, S. Zimmermann, L. Nunez, R. Rossman, K. Reid, K. Moelling, G. D. Yancopoulos, and D. J. Glass. 1999. Differentiation stage-specific inhibition of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway by Akt. Science 286:1738-1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosen, K. M., B. M. Wentworth, N. Rosenthal, and L. Villa-Komaroff. 1993. Specific, temporally regulated expression of the insulin-like growth factor II gene during muscle cell differentiation. Endocrinology 133:474-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ryuto, M., M. Ono, H. Izumi, S. Yoshida, H. A. Weich, K. Kohno, and M. Kuwano. 1996. Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor by tumor necrosis factor alpha in human glioma cells. Possible roles of SP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 271:28220-28228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sakuta, T., K. Matsushita, N. Yamaguchi, T. Oyama, R. Motani, T. Koga, S. Nagaoka, K. Abeyama, I. Maruyama, H. Takada, and M. Torii. 2001. Enhanced production of vascular endothelial growth factor by human monocytic cells stimulated with endotoxin through transcription factor SP-1. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:233-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwarz, E. R., M. T. Speakman, M. Patterson, S. S. Hale, J. M. Isner, L. H. Kedes, and R. A. Kloner. 2000. Evaluation of the effects of intramyocardial injection of DNA expressing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in a myocardial infarction model in the rat—angiogenesis and angioma formation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 35:1323-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Semenza, G. L. 2000. HIF-1 and human disease: one highly involved factor. Genes Dev. 14:1983-1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Semsarian, C., M. J. Wu, Y. K. Ju, T. Marciniec, T. Yeoh, D. G. Allen, R. P. Harvey, and R. M. Graham. 1999. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy is mediated by a Ca2+-dependent calcineurin signalling pathway. Nature 400:576-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shah, O. J., J. C. Anthony, S. R. Kimball, and L. S. Jefferson. 2000. 4E-BP1 and S6K1: translational integration sites for nutritional and hormonal information in muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 279:E715-E729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shi, Q., X. Le, J. L. Abbruzzese, Z. Peng, C. N. Qian, H. Tang, Q. Xiong, B. Wang, X. C. Li, and K. Xie. 2001. Constitutive Sp1 activity is essential for differential constitutive expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 61:4143-4154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shioi, T., P. M. Kang, P. S. Douglas, J. Hampe, C. M. Yballe, J. Lawitts, L. C. Cantley, and S. Izumo. 2000. The conserved phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway determines heart size in mice. EMBO J. 19:2537-2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith, R. C., D. Branellec, D. H. Gorski, K. Guo, H. Perlman, J.-F. Dedieu, C. Pastore, A. Mahfoudi, P. Denèfle, J. M. Isner, and K. Walsh. 1997. p21CIP1-mediated inhibition of cell proliferation by overexpression of the gax homeodomain gene. Genes Dev. 11:1674-1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Springer, M. L., A. S. Chen, P. E. Kraft, M. Bednarski, and H. M. Blau. 1998. VEGF gene delivery to muscle: potential role for vasculogenesis in adults. Mol. Cell 2:549-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stein, I., A. Itin, P. Einat, R. Skaliter, Z. Grossman, and E. Keshet. 1998. Translation of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA by internal ribosome entry: implications for translation under hypoxia. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:3112-3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stoner, M., F. Wang, M. Wormke, T. Nguyen, I. Samudio, C. Vyhlidal, D. Marme, G. Finkenzeller, and S. Safe. 2000. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in HEC1A endometrial cancer cells through interactions of estrogen receptor alpha and Sp3 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 275:22769-22779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tanaka, T., H. Kanai, K. Sekiguchi, Y. Aihara, T. Yokoyama, M. Arai, T. Kanda, R. Nagai, and M. Kurabayashi. 2000. Induction of VEGF gene transcription by IL-1 beta is mediated through stress-activated MAP kinases and Sp1 sites in cardiac myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 32:1955-1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Toker, A., and A. C. Newton. 2000. Akt/Protein Kinase B is regulated by autophosphorylation at the hypothetical PDK-2 site. J. Biol. Chem. 275:8271-8274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tollefsen, S. E., J. L. Sadow, and P. Rotwein. 1989. Coordinate expression of insulin-like growth factor II and its receptor during muscle differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:1543-1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ueki, K., R. Yamamoto-Honda, Y. Kaburagi, T. Yamauchi, K. Tobe, B. M. Burgering, P. J. Coffer, I. Komuro, Y. Akanuma, Y. Yazaki, and T. Kadowaki. 1998. Potential role of protein kinase B in insulin-induced glucose transport, glycogen synthesis, and protein synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 273:5315-5322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ushio-Fukai, M., R. W. Alexander, M. Akers, Q. Yin, Y. Fujio, K. Walsh, and K. K. Griendling. 1999. Reactive oxygen species mediate the activation of Akt/protein kinase B by angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274:22699-22704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Verdu, J., M. A. Buratovich, E. L. Wilder, and M. J. Birnbaum. 1999. Cell-autonomous regulation of cell and organ growth in Drosophila by Akt/PKB. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:500-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vincent, K. A., K. G. Shyu, Y. Luo, M. Magner, R. A. Tio, C. Jiang, M. A. Goldberg, G. Y. Akita, R. J. Gregory, and J. M. Isner. 2000. Angiogenesis is induced in a rabbit model of hindlimb ischemia by naked DNA encoding an H1F-1alpha/VP16 hybrid transcription factor. Circulation 102:2255-2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zundel, W., C. Schindler, D. Haas-Kogan, A. Koong, F. Kaper, E. Chen, A. R. Gottschalk, H. E. Ryan, R. S. Johnson, A. B. Jefferson, D. Stokoe, and A. J. Giaccia. 2000. Loss of PTEN facilitates HIF-1-mediated gene expression. Genes Dev. 14:391-396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]