Abstract

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SAGA complex is required for the normal transcription of a large number of genes. Complex integrity depends on three core subunits, Spt7, Spt20, and Ada1. We have investigated the role of Spt7 in the assembly and function of SAGA. Our results show that Spt7 is important in controlling the levels of the other core subunits and therefore of SAGA. In addition, partial SAGA complexes containing Spt7 can be assembled in the absence of both Spt20 and Ada1. Through biochemical and genetic analyses of a series of spt7 deletion mutants, we have identified a region of Spt7 required for interaction with the SAGA component Spt8. An adjacent Spt7 domain was found to be required for a processed form of Spt7 that is present in a previously identified altered form of SAGA called SLIK, SAGAalt, or SALSA. Analysis of an spt7 mutant with greatly reduced levels of SLIK/SAGAalt/SALSA suggests a subtle role for this complex in transcription that may be redundant with a subset of SAGA functions.

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SAGA (Spt-Ada-Gcn5 acetyltransferase) complex is a multisubunit coactivator complex that is important for transcription in vivo (27, 32). Whole-genome mRNA analysis of SAGA mutants has shown that the expression of approximately 10% of S. cerevisiae genes are affected by the loss of the SAGA complex (23). Both in vivo and in vitro experiments have shown that SAGA activates transcription after its recruitment by transcriptional activators (5, 22, 42, 43). Other results have suggested that SAGA also represses transcription at particular promoters (4, 23). In addition, several studies have shown that SAGA often acts coordinately with other coactivator complexes at a promoter to achieve normal levels of transcription (27). The SAGA complex is conserved between yeast and humans, strongly suggesting that this type of coactivator is also important in mammalian transcription (6, 25, 26, 28, 46).

The subunits in SAGA can be grouped functionally based on a large body of in vivo and in vitro experiments (27). Three classes of SAGA proteins are involved in distinct aspects of transcriptional control. First, Gcn5 contains the catalytic activity for the histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity of SAGA (8), and Gcn5's HAT activity is modulated by the Ada2 and Ada3 proteins (2, 16, 39). Second, Spt3 and Spt8 of SAGA have been shown to control the TATA box binding protein (TBP)-TATA interaction at particular promoters (4, 5, 9, 11, 22). Third, Tra1 has been shown to interact with several transcriptional activators in vitro, suggesting that SAGA is recruited to promoters via this subunit and subsequently activates or represses transcription through its different activities (7).

SAGA also contains two additional classes of proteins that are not known to participate directly in regulation and therefore may serve structural roles. In the first class are three proteins, Spt7, Spt20, and Ada1, that function as SAGA core components based on their requirement for integrity of the complex. SAGA is absent from spt7Δ, spt20Δ, and ada1Δ mutants, as assayed by Western analysis and HAT assays (16, 38). Moreover, these mutations cause a broad variety of severe phenotypes, consistent with a complete loss of SAGA function (21, 30, 38). The second class contains a subset of the Tafs (Tafs 5, 6, 9, 10, and 12), proteins initially identified as components of the TFIID complex (17). In referring to the Tafs, we are using the recently revised uniform Taf nomenclature (41). At least one of the Tafs, Taf12, appears to be important for SAGA structure, as its removal via a taf12 temperature sensitivity mutation affects both SAGA integrity as well as its nucleosomal HAT activity (17).

While the control of transcription by SAGA has been extensively studied, less is known about the control of its assembly and the protein-protein associations within the complex. Previous studies have shown that both Spt7 and Ada1 have histone fold motifs that interact with Taf components of SAGA: Ada1 with Taf12 and Spt7 with Taf10 (13, 14). However, it is not known how the core subunits contribute toward the structural integrity of the complex. To learn more about the roles of one of the SAGA core components, we have chosen Spt7 as the focus of our studies. Spt7 is a 1,332-amino-acid, highly negatively charged protein whose sequence contains two motifs of note. First, as mentioned previously, Spt7 contains a histone fold (amino acids 979 to 1045) required for interaction with the Taf10 subunit of SAGA (13). Second, Spt7 contains a bromodomain (amino acids 463 to 523), a motif found in many transcription factors (20; reviewed in reference 44). A deletion that removes the Spt7 bromodomain does not cause any detectable phenotypes, suggesting that this domain is either redundant or not crucial for Spt7 function (15, 38).

Previous studies suggest that Spt7 may act dynamically to regulate SAGA function. These studies demonstrated that SAGA exists in at least one alternate form that has been named SLIK (SAGA-like), SAGAalt, or SALSA (4, 18, 34; D. Sterner and S. Berger, personal communication). This complex is referred to hereafter as SLIK/SALSA. The SLIK/SALSA complex has two identified differences from SAGA: a smaller form of Spt7 and the absence of Spt8 (4; Patrick Grant, personal communication). Although little is known about the formation of SLIK/SALSA, evidence suggests involvement of the general amino acid control pathway, because SLIK/SALSA levels increase in cells grown in amino acid starvation conditions (4). However, the requirements for SLIK/SALSA formation, as well as its functions in vivo, remain unknown.

In this study, we examine several aspects of Spt7 protein structure and function. We demonstrate that Spt7 is involved in regulating the levels of Spt20 and Ada1, the two other SAGA core components, suggesting that Spt7 levels control the amount of SAGA present in vivo. Additional experiments reveal that partial Spt7-containing complexes form in the absence of the other core components. To determine regions of function and interaction with other subunits, we generated and analyzed a set of spt7 partial deletion mutants. This analysis allowed us to delineate a region of minimal function in Spt7 as well as a domain for Spt8 interaction. Moreover, we have defined a region of Spt7 that is required for its processing and, hence, for the formation of SLIK/SALSA. Analysis of the spt7 mutant that impairs processing suggests that SLIK/SALSA is not strongly required for transcriptional activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and methods.

All S. cerevisiae strains used in this study (Table 1) are descended from a GAL2+ derivative of S288C (45). All of the spt3Δ, spt8Δ, gcn5Δ, spt20Δ, and ada1Δ alleles used, as well as spt7Δ402, have been described previously (12, 15, 30, 38). Standard methods for mating, sporulation, transformations, and tetrad analysis were used, and all media were prepared as previously described (31). The Spt phenotype caused by spt7 mutations was scored with respect to two insertion mutations, his4-917δ and lys2-173R2. In an SPT7+ (Spt+) strain, these insertions confer His− and Lys+ phenotypes, respectively; in an spt7 null strain (Spt−), these insertion mutations cause His+ and Lys− phenotypes (15).

TABLE 1.

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| FY3 | MATaura3-52 |

| FY632 | MATa/MATα his4-917δ his4-917δ lys2-173R2/lys2-173R2 leu2Δ1 leu2Δ1 ura3-52/ ura3-52 trp1Δ63/trp1Δ63 |

| FY971 | MATagcn4Δ::LEU2 lys2-173R2 leu2Δ1 ura3-52 |

| FY1093 | MATaspt7Δ402::LEU2 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ1 ura3-52 trp1Δ63 ade8 |

| FY1291 | MATα spt20Δ200::ARG4 arg4-12 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 lys2-173R2 ura3-52 |

| FY1977 | MATα HA-SPT20 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2025 | MATaHA-SPT7-Myc ura3Δ0 his3Δ200 leu2Δ0 lys2-128δ |

| FY2026 | MATaHA-SPT20 his3Δ200 spt7Δ403::URA3 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 lys2-128δ |

| FY2027 | MATaHA-SPT20 ada1Δ::HIS3 his3Δ200 leu2Δ0 lys2-173R2 his4-917δ ura3Δ0 trp1Δ63 |

| FY2028 | MATaspt7Δ404::HIS3 ura3Δ0 his3Δ200 leu2Δ0 lys2-128δ |

| FY2029 | MATaHA-spt7-100 ura3-52 his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 |

| FY2030 | MATaHA-SPT7 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 |

| FY2031 | MATaHA-SPT7-TAP::TRP1 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 |

| FY2032 | MATaHA-spt7-1125-TAP::TRP1 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 |

| FY2033 | MATaHA-spt7-1180-TAP::TRP1 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 |

| FY2034 | MATaHA-SPT7-TAP::TRP1 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 gcn5Δ::HIS3 trp1Δ63 lys2-173R2 |

| FY2035 | MATaHA-SPT7-TAP::TRP1 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 ada1Δ::HIS3 lys2-173R2 his4-917δ |

| FY2036 | MATaHA-SPT7-TAP::TRP1 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 spt20Δ100::URA3 |

| FY2037 | MATaHA-SPT7-TAP::TRP1 trp1Δ63 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 spt8Δ302::LEU2 ura3-52 |

| FY2038 | MATaHA-SPT7-Myc leu2Δ1 spt8Δ302::LEU2 ura3-52 lys2-128δ his4-917δ trp1Δ63 |

| FY2039 | MATα HA-SPT7-Myc leu2Δ0 spt8Δ302::LEU2 ura3-52 trp1Δ63 |

| FY2040 | MATaHA-SPT7-TAP::TRP1 trp1Δ63 spt3Δ203::TRP1 ura3Δ0 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 |

| FY2041 | MATaHA-SPT7-TAP ada1Δ::HIS3 spt20Δ100::URA3 his4-917δ trp1Δ63 lys2-173R2 his3Δ200 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2042 | MATaHA-spt7-873-TAP::TRP1 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 |

| FY2043 | MATaHA-spt7-200-TAP::TRP1 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 |

| FY2044 | MATaHA-spt7-300-TAP::TRP1 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 |

| FY2045 | MATaHA-spt7-200-Myc ura3Δ0 his3Δ200 leu2Δ0 lys2-128δ |

| FY2046 | MATaHA-spt7-300-Myc ura3Δ0 his3Δ200 leu2Δ0 lys2-128δ |

| FY2047 | MATα HA-spt7-200-TAP::TRP1 arg4-12 ura3-52 trp1Δ63 lys2-173R2 |

| FY2048 | MATα HA-spt7-300-TAP::TRP1 arg4-12 trp1Δ63 lys2-173R2 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2049 | MATaHA-spt7-400-TAP::TRP1 lys2-173R2 trp1Δ63 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2050 | MATaHA-spt7-1180-TAP::TRP1 spt8Δ302::LEU2 his4-917δ trp1Δ63 leu2Δ0 ura3-52 lys2-173R2 |

| FY2051 | MATaHA-spt7-1180-TAP::TRP1 gcn5Δ::HIS3 lys2-173R2 leu2Δ1 ura3Δ0 trp1Δ63 |

| FY2052 | MATaHA-spt7-1180-TAP::TRP1 spt3-401 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 ura3-52 |

| FY2053 | MATaHA-spt7-1125-TAP::TRP1 spt8Δ302::LEU2 his4-917δ trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 ura3-52 lys2-173R2 |

| FY2054 | MATaHA-spt7-1125-TAP::TRP1 gcn5Δ::HIS3 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 lys2-173R2 |

| FY2055 | MATα HA-spt7-1125-TAP::TRP1 spt3-401 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3Δ0 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2056 | MATaHA-spt7-200-TAP::TRP1 spt8Δ302::LEU2 ura3-52 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2057 | MATα HA-spt7-200-TAP::TRP1 gcn5Δ::HIS3 ura3Δ0 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2058 | MATα HA-spt7-200-TAP::TRP1 spt3-401 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ1 ura3Δ0 trp1Δ63 |

| FY2059 | MATaHA-spt7-300-TAP::TRP1 spt8Δ302::LEU2 ura3-52 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2060 | MATaHA-spt7-300-TAP::TRP1 gcn5Δ::HIS3 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ1 arg4-12 ura3Δ0 trp1Δ63 |

| FY2061 | MATaHA-spt7-300-TAP::TRP1 spt3-401 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ1 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2062 | MATa/MATα HA-spt7-100/ HA-spt7-873-TAP::TRP1 ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0 his3Δ200/HIS3 leu2Δ0/ leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ/lys2-173R2 trp1Δ63/TRP1 his4-917δ/HIS4 |

| FY2063 | MATa/MATα HA-spt7-100/HA-spt7-100-TAP::TRP ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0 his3Δ200/his3Δ200 leu2Δ1/leu2Δ0 lys2-128δ/lys2-128δ trp1Δ63/TRP1 |

| FY2064 | MATa/MATα HA-spt7-873-Myc/HA-spt7-873-TAP::TRP1 ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1/leu2Δ0 trp1Δ63/TRP1 his4-917δ/HIS4 his3Δ200/HIS3 lys2-173R2/lys2-128δ |

| FY2065 | MATa/MATα spt7Δ403::URA3/spt7Δ404::HIS3 ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0 his3Δ200/his3Δ200 leu2Δ0/leu2Δ0 lys2-128δ/lys2-128δ |

| L861 | MATα spt3-401 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ1 ura3-52 |

The spt7 null mutations spt7Δ403::URA3 and spt7Δ404::HIS3 were constructed by standard methods (3, 24). Deletions that remove specific sequences of SPT7 were constructed using previously described plasmids and procedures (35). We replaced the amino- or carboxy-terminal regions of SPT7 with the hemagglutinin (HA) or Myc epitopes by PCR-mediated integration. To construct strains containing tandem affinity purification (TAP)-tagged SPT7, we used plasmid pBS1479 as previously described (29). Selection was done using the Kluyveromyces lactis TRP1 gene. The spt7 internal deletions spt7-200, spt7-300, and spt7-400 were constructed by integrating plasmids pJW10, pJW11, and pJW12, respectively, via a two-step method. First, the plasmid was digested with EcoNI and used to transform the appropriate strain to Ura+. Second, recombinants that excised the intervening URA3 marker were identified after overnight growth in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YEPD) liquid media and plating on 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) solid media. Verification of the correct integration and recombination events was performed by PCR.

Plasmid DNA construction and analysis.

Plasmids were constructed, maintained, and isolated from Escherichia coli strains DH5α (1) and MH1 (19) by standard methods (1). Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, and Taq polymerase were purchased from New England Biolabs and Gibco BRL. Plasmid pJW9 contained base pairs 3116 to 3999 of SPT7 subcloned into the integrating URA3 plasmid pRS406 (37). Plasmids pJW10, pJW11, and pJW12, used for construction of spt7-200, spt7-300, and spt7-400, respectively, were generated using the Stratagene QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit.

TAP purifications.

TAP purifications were performed as previously described (29) but with several modifications. All steps, except the tobacco etch virus cleavage, were performed at 4°C. Briefly, 2 liters of cells grown to approximately 2 × 107 cells/ml in YEPD were concentrated in 10 ml of extract buffer (40 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 350 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Tween, 2 μg of pepstatin A/ml, 2 μg of leupeptin/ml, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]), and whole-cell extracts were prepared by bead beating in a mini-beadbeater. Cellular debris was removed by spinning extracts at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The extract was cleared by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h. For the TAP purification, 800 μl of 1:1 immunoglobulin G (IgG)-Sepharose (Sigma) slurry was incubated with clarified lysate for 3 h. Beads were washed with 20 ml of extract buffer followed by 10 ml of TEV cleavage buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 0.5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) and then resuspended in 1 ml of the TEV cleavage buffer. TEV cleavage was performed using 10 μl (100 U) of TEV (Gibco BRL) for 2.5 h at 14°C. TEV-cleaved products were added to 3 ml of calmodulin binding buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgOAc, 1 mM imidazole, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.1% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol) along with 3 μl of 1 M CaCl2 for each milliliter of TEV elution. Calmodulin-Sepharose (Stratagene) purification was performed by binding eluate to 400 μl of bead slurry for 2 h at 4°C. Proteins bound to calmodulin beads were eluted in 0.2-ml fractions using calmodulin elution buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgOAc, 1 mM imidazole, 2 mM EGTA, 0.1% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol). TAP-purified complexes were run on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (5 to 20% acrylamide) gradient gel. Silver staining was performed according to the protocol from the Yeast Resource Center at the University of Washington (http://depts.washington.edu/∼yeastrc/ms_silver.htm). Gels were dried under vacuum at 80°C for 1 h.

Western analysis.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared as described above, and protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts of whole cell extracts, column fractions, or TAP-purified complexes were separated on SDS-PAGE gels. Transfer was performed as previously described (40a). The following antibodies were used at the given concentrations: HA (12CA5 from Boehringer Mannheim, 1:2,500), Myc (A14 from Santa Cruz, 1:1,000), Ada1 (1:2,000), Spt20 (1:1,000), Spt7 (1:1,000), Taf1 (1:2,000), Taf6 (1:2,000), Taf10 (1:2,000), Taf12 (1:1,000), Spt3 (1:1,000), Spt8 (1:1,000), Ada2 (1:1,000), and Gcn5 (1:1,000). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad) were used at a 1:5,000 dilution and were detected by chemiluminescence.

Mono Q fractionations.

Extracts were fractionated using a Mono Q column on an AKTA fast-performance liquid chromatograph (FPLC) (Amersham Pharmacia) (10). Cells were grown in 1 liter of YEPD to approximately 2 × 107 cells/ml, and clarified lysate was prepared as described in the previous section. Purification of approximately 10 mg of extract was achieved by fractionation on a 1-ml Mono Q column with a 100 to 500 mM NaCl gradient in the following buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10% glycerol, 0.1% Tween 20, and protease inhibitors (2 μg of leupeptin/ml, 2 μg of pepstatin A/ml, 1 mM PMSF). Every other fraction was analyzed by Western blotting for the presence of SAGA subunits.

RNA isolation and Northern analysis.

To prepare RNA for Northern analyses, cells were grown in liquid media to a concentration of 1 × 107 to 2 × 107 cells/ml. For induction of HIS3 and TRP3, 40 mM 3-aminotriazole (Sigma) was added to cells grown in SC-His; cultures were induced for 2 h before harvesting. RNA isolation and Northern analysis were performed as previously described (1, 40). All probes were synthesized by PCR amplification of each open reading frame from genomic DNA and labeled with [α-32P]dATP by random priming (1). RNA levels were quantitated using the Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager and normalized to the level of ACT1 mRNA.

RESULTS

Levels of Spt20 and Ada1 are dependent on Spt7.

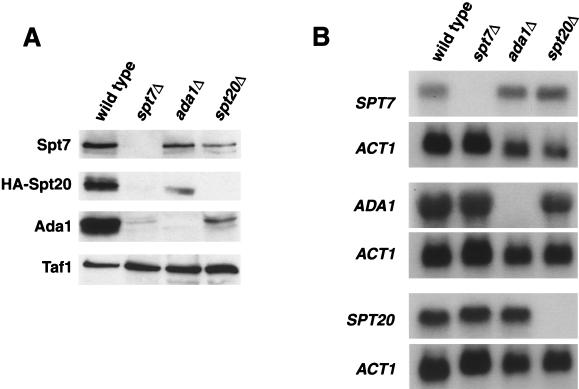

Both biochemical and genetic evidence implicate Spt7, Spt20, and Ada1 as core components of the SAGA complex. From these studies, no distinction is apparent between the requirement for Spt7, Spt20, or Ada1 in SAGA integrity or assembly. To test if they might control each other's protein levels, we measured the amounts of these three core components in spt7Δ, spt20Δ, and ada1Δ mutants. Western blottings of whole-cell extracts (Fig. 1A) demonstrated that in an spt7Δ mutant, both Spt20 and Ada1 proteins are barely detectable. Conversely, the level of Spt7 is only mildly decreased in an ada1Δ mutant, although a more significant decrease is observed in an spt20Δ mutant. Finally, Spt20 and Ada1 affect each other's levels, although the effects are not nearly as severe as those caused by spt7Δ. These results suggest that Spt7 plays an important in vivo role in maintaining appropriate levels of these other two SAGA core components and therefore in determining the level of the entire SAGA complex.

FIG. 1.

Levels of Spt20 and Ada1 are dependent on Spt7. (A) Western analysis was performed to measure the levels of Spt7, Spt20, and Ada1. Wild-type (strain FY1977), spt7Δ (FY2026), spt20Δ (FY1291), and ada1Δ (FY2027) strains were grown in YEPD medium, and whole-cell extracts were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis, using antibodies to Spt7, Ada1, and HA (to detect the HA-Spt20 fusion protein). Taf1 levels were measured as a loading control. (B) Northern analysis of mRNA levels in spt7Δ, spt20Δ, and ada1Δ mutants. The same wild-type, spt7Δ, spt20Δ, and ada1Δ strains were grown in YEPD medium, and RNA was isolated and analyzed by Northern analysis. ACT1 mRNA levels were measured as a loading control.

As SAGA is a transcriptional coactivator, we wanted to determine whether the reduction in protein levels observed in spt7Δ, spt20Δ, and ada1Δ mutants occurs transcriptionally or posttranscriptionally. Northern analysis (Fig. 1B) shows that deletion of either SPT7, SPT20, or ADA1 does not significantly alter the mRNA levels of the two remaining genes. The only reproducible effect observed was an approximately twofold increase in the level of SPT7 mRNA in ada1Δ and spt20Δ mutants; however, this increase does not correlate with the decreased Spt7 protein levels in these strains. Thus, the effect on core component protein levels in spt7Δ, spt20Δ, and ada1Δ mutants is posttranscriptional, probably at the level of stability.

Partial SAGA complexes form in spt20Δ and ada1Δ mutants.

The results described in the previous section demonstrate the importance of Spt7 in the integrity of the SAGA complex. As a significant level of Spt7 exists in spt20Δ and ada1Δ mutants, it is possible that partial SAGA complexes assemble in these strains. To gain insight into the protein interactions within SAGA and potential intermediates in complex formation, we used the TAP tag to purify Spt7-containing complexes. First, we constructed a version of SPT7 that encodes a TAP tag at the carboxy terminus of Spt7 and an HA epitope tag at the amino terminus. This version of SPT7, HA-SPT7-TAP, encodes wild-type Spt7 function by all phenotypes tested (data not shown). Second, strains were constructed that contained HA-SPT7-TAP in combination with deletions of genes that encode other SAGA components. Then, Spt7 and associated proteins were purified (see Materials and Methods) and were analyzed on silver-stained gradient SDS-PAGE gels (Fig. 2) and by Western analysis (Fig. 3). Silver stains were used as the primary indication for the presence of SAGA subunits, and these data were supplemented with Western analyses for the detection of low levels of associated proteins. In a wild-type background, the form of SAGA purified by Spt7-TAP (Fig. 2, lane 1) appeared to be identical to SAGA as previously purified by conventional chromatography (16).

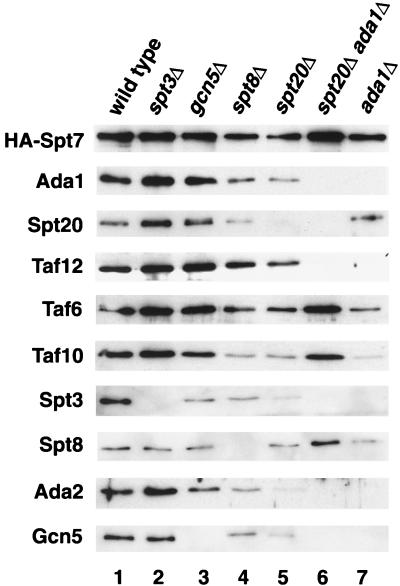

FIG. 2.

Characterization of SAGA purified from wild-type and SAGA mutant strains. TAP-purified complexes from wild-type (strain FY2031), spt3Δ (FY2040), gcn5Δ (FY2034), spt8Δ (FY2037), ada1Δ (FY2035), spt20Δ ada1Δ (FY2041), and spt20Δ (FY2036) strains were prepared, run on SDS-PAGE (5 to 20% acrylamide) gels, and silver stained. The amount of each complex loaded was adjusted to have an equal level of Spt7 in each lane. All samples were run on one gel.

FIG. 3.

Western analysis of TAP-purified mutant SAGA complexes. TAP-purified complexes from the same extracts as in Fig. 2 were run on SDS-PAGE gels and Western blotted using the following antibodies: HA (12CA5), Ada1, Spt20, Taf6, Taf10, Taf12, Spt3, Spt8, Ada2, and Gcn5.

As expected, both spt20Δ and ada1Δ mutations caused major disruptions to SAGA; however, partial complexes are present in both mutants. The ada1Δ mutant produced a partial complex that contained detectable levels of Spt8, Taf5, Taf6, Taf9, and Taf10 (Fig. 2, lane 7) by silver staining and a small amount of Spt20 visible by Western analysis (Fig. 3, lane 7). The absence of Taf12 agrees with a previously described interaction between Taf12 and Ada1 (14). The spt20Δ mutant also produced an altered complex distinct from that produced in either the wild-type or ada1Δ mutant (Fig. 2, lane 5). Although the silver stain shows the presence of only a few SAGA subunits, including Spt8, Taf6, Taf9, Taf10, and Ada1 (Fig. 2, lane 5), Western analysis indicates that this complex contained low but detectable levels of all SAGA proteins for which we tested (Fig. 3, lane 5). Finally, we also examined an ada1Δ spt20Δ double mutant and found that four SAGA proteins were still associated with Spt7, including Taf6, Taf9, Taf10, and Spt8 (Fig. 3, lane 6). The association of Taf10 with Spt7 in the absence of other core components supports previous findings (13).

Several conclusions can be made from these data. First, both Ada1 and Spt20 can associate with Spt7 in the absence of the other core member, albeit at reduced levels. Second, Tra1, the SAGA subunit required for the recruitment of SAGA by transcriptional activators in vitro (7), requires both Ada1 and Spt20 to be present in SAGA. Since SAGA from an spt20Δ mutant is still associated with at least most of the other known SAGA components, this result suggests that Tra1 is not absolutely required for normal assembly of other SAGA components. Third, we can tentatively assign four other SAGA proteins, Taf12, Spt3, Gcn5, and Ada2, as requiring Ada1 for association in SAGA. Fourth, the fact that at least four SAGA subunits associate with Spt7 in the ada1Δ spt20Δ double mutant suggests that they interact directly with Spt7 or with each other. Overall, these results demonstrate that Spt7, Spt20, and Ada1 are each required in distinct ways for the formation of SAGA and that partial SAGA complexes can form in the absence of two of the core subunits.

To determine the dependence of SAGA on three members involved in transcriptional control, we also purified SAGA from spt3Δ, spt8Δ, and gcn5Δ mutants. In contrast to loss of the core subunits, for each of these mutants we detected only the loss of the subunit corresponding to the deleted gene (Fig. 2 and 3, compare lane 1 with lanes 2, 3, and 4). Therefore, each of these proteins associates with SAGA independently of the others. These results correlate with previous data that showed that Spt3 and Spt8 are not dependent upon each other for their association with SAGA and that loss of each protein has only mild effects on the complex (38).

Biochemical and genetic characterization of Spt7 carboxy-terminal deletions.

Based on past studies and our new results described in the previous section, Spt7 has an important structural role within SAGA, perhaps as a scaffold for several SAGA components. To determine regions of Spt7 required for interactions with other SAGA components, we constructed a set of spt7 deletion mutations at the endogenous SPT7 locus (see Materials and Methods). Since past work suggested that the carboxy-terminal portion of Spt7 was important for Spt7 function (13, 15), the deletions were constructed to remove increasing amounts from this end of the protein (Fig. 4A). These strains were then examined for a set of mutant phenotypes (Fig. 4B) and for the composition of the SAGA complex (Fig. 5). A deletion mutation that removes the carboxy-terminal 459 amino acids, spt7-873, confers phenotypes close to those of an spt7 null mutation (Fig. 4B). Although it produces a stable product (Fig. 5, lane 6), this truncated protein does not associate with any SAGA components stoichiometrically. The region of SPT7 missing in Spt7-873 contains the previously identified histone fold motif (amino acids 979 to 1045) (13). As we describe in a later section, expression of only these carboxy-terminal 459 amino acids is largely sufficient for Spt7 function.

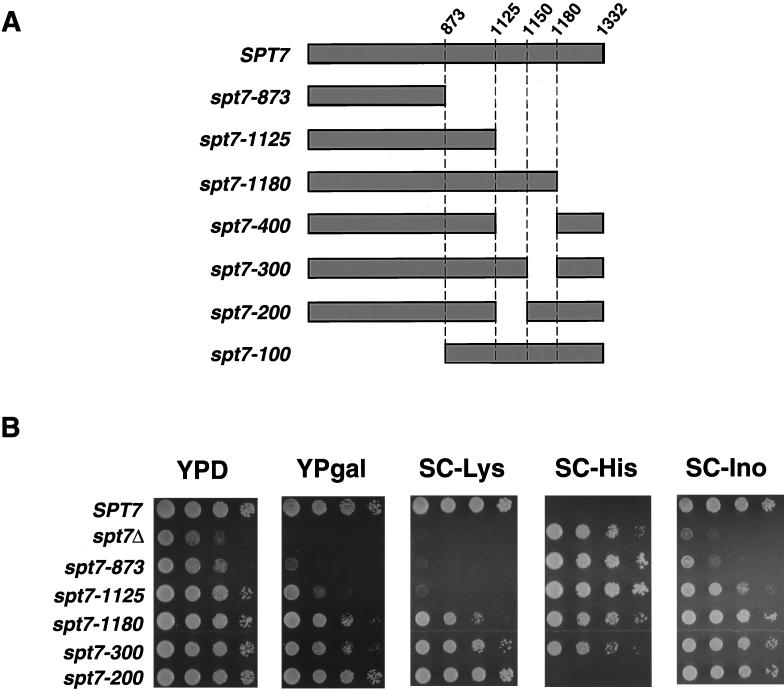

FIG. 4.

Spt7 deletion analysis. (A) Diagram of Spt7 deletion mutants described in this study. Deletion mutations were constructed as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Phenotypic and biochemical analyses of spt7 deletion mutants. The strains used are as follows: wild-type (strain FY2031), spt7Δ (FY1093), spt7-873 (FY2042), spt7-1125 (FY2032), spt7-1180 (FY2033), spt7-300 (FY2044), and spt7-200 (FY2043). All strains contain the his4-917δ and lys2-173R2 alleles for determining the Spt phenotype (see Materials and Methods). An Spt− phenotype corresponds to growth on media lacking histidine and no growth on media lacking lysine. Cells were grown to saturation overnight in YEPD medium and spotted in a dilution series from 108 to 104 cells/ml, and the plates were incubated at 30°C. The plates shown were incubated for the following times: YEPD, 2 days; SC-Lys, 3 days; SC-His, 4 days; YPgal, 3 days; SC, 2 days; and SC-Ino, 2 days.

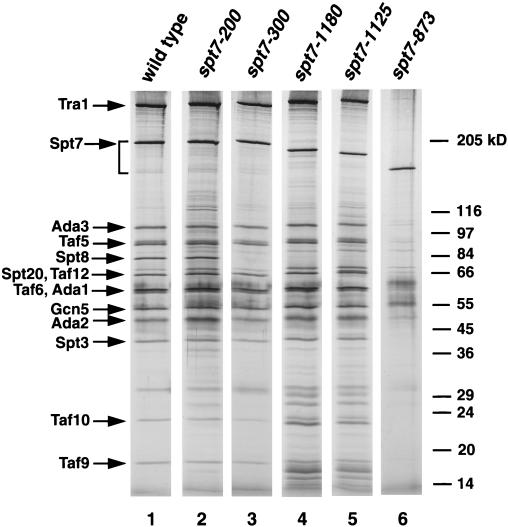

FIG. 5.

Silver stain of SAGA purified from wild-type and spt7 mutant strains. TAP-purified SAGA complex from strains analyzed for phenotypes in Fig. 4B were visualized on an SDS-PAGE (5 to 20% acrylamide) gel by silver stain. The amount of each complex loaded was adjusted to have an equal level of Spt7 in each lane. All samples were run on one gel. The additional faint bands present in lanes 4 and 5 were not observed reproducibly and are not part of SAGA.

Two smaller deletion mutations that leave the histone fold motif intact, spt7-1180 and spt7-1125, cause different mutant phenotypes and were studied further. The larger deletion mutant, spt7-1125, causes stronger Gal−, Ino−, and Spt− phenotypes than does spt7-1180 (Fig. 4B; Table 2), although the proteins are present at the same level (data not shown). To correlate the phenotypes with biochemical interactions, we purified SAGA from these strains. For both deletions, the only detectable difference from wild-type SAGA was the absence of Spt8, indicating that a region in the carboxy-terminal 152 amino acids of Spt7 is required for the association of Spt8 with SAGA (Fig. 5, compare lane 1 with lanes 4 and 5). This result is further supported by the observation that the carboxy-terminal 459 amino acids of Spt7 are sufficient for interactions with Spt8 (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Genetic analysis of spt7 deletion mutants

| Relevant genotype | Phenotypesa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth | Spt | Ino | Gal | |

| SPT7+ | + | + | + | + |

| spt8Δ | +/− | −/+ | + | +/− |

| gcn5Δ | +/− | +/− | + | +/− |

| spt8Δ gcn5Δ | − | − | − | −/+ |

| spt7-1180 | +/− | −/+ | + | +/− |

| spt7-1180 spt8Δ | +/− | −/+ | + | +/− |

| spt7-1180 gcn5Δ | − | − | −/+ | −/+ |

| spt7-300 | +/− | +/− | + | +/− |

| spt7-300 spt8Δ | +/− | −/+ | + | +/− |

| spt7-300 gcn5Δ | − | − | −/+ | −/+ |

| spt7-1125 | −/+ | − | +/− | −/+ |

| spt7-1125 spt8Δ | −/+ | − | +/− | −/+ |

| spt7-1125 gcn5Δ | − | − | − | − |

| spt7-200 | + | + | + | + |

| spt7-200 spt8Δ | −/+ | − | +/− | −/+ |

| spt7-200 gcn5Δ | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− |

Representative strains for each genotype tested above are listed in Table 1. Growth was assessed by streaking for single colonies on YEPD plates, and other phenotypes were determined by replica plating. All phenotypes were scored as +, +/−, −/+, or − (+, wild-type phenotype; −, the spt7 null phenotype). The phenotypes tested were as follows: Ino, inositol auxotrophy; Gal, utilization of galactose as the sole carbon source; Spt, suppression of the lys2-173R2 and/or his4-917δ alleles.

Since spt7-1125 causes more severe phenotypes than does spt7-1180, we analyzed the region between amino acids 1125 and 1180 in greater detail. First, we constructed an internal deletion of this region (spt7-400; Fig. 4A) and observed that this mutation caused phenotypes identical to those of spt7-1125 (data not shown). Next, we divided this region by two smaller deletions: spt7-200 removes codons 1125 to 1150 and spt7-300 removes codons 1150 to 1180 (Fig. 4A). The spt7-300 mutation caused phenotypes very similar to those of spt7-1180 (Fig. 4B). We also noted that both spt7-1180 and spt7-300 caused phenotypes very similar to an spt8Δ mutation (Table 2). Consistent with these mutant phenotypes, Spt8 failed to associate with SAGA in the spt7-300 mutant (Fig. 5, lane 3). These results strongly suggest that a region of Spt7 that spans amino acid 1180 is required for interaction with Spt8. In contrast, analysis of the spt7-200 mutant showed that it was phenotypically distinct from spt7-300. The spt7-200 mutation caused no mutant phenotypes among those tested (Fig. 4B), and Spt8 is still associated with SAGA in this mutant (Fig. 5, lane 2). The spt7-200 mutant is also wild type for several additional phenotypes that are possessed by an spt7 null mutant, including sensitivities to caffeine, hydroxyurea, formamide, 3-aminotriazole, and mycophenolic acid and the inability to utilize glycerol as the sole carbon source (data not shown). Therefore, while the spt7-200 deletion strengthens mutant phenotypes when combined with deletion of the adjacent region, it does not cause detectable phenotypes in an otherwise wild-type background. Thus, two regions of Spt7 are defined by these deletions: one required for association with Spt8 and a second shown in a later section to be required for carboxy-terminal processing.

Further genetic characterization of Spt7 carboxy-terminal deletions.

To test if the spt7-1180 and spt7-300 mutations are truly genetically equivalent to spt8Δ, we performed three additional genetic tests. First, double mutants were constructed between spt8Δ and each of these spt7 mutations. If the sole defect in these spt7 mutants was loss of Spt8, then the double mutants should have no greater phenotype than any of the single mutants. Indeed, this result was observed (Table 2; compare spt8Δ, spt7-1180, spt7-1180 spt8Δ, spt7-300, and spt7-300 spt8Δ). Second, double mutants were constructed between each of these spt7 mutations and gcn5Δ. Previous results showed that spt8Δ gcn5Δ double mutants have more severe phenotypes than either single mutant. Again, the spt7 mutations mimicked the spt8Δ mutation, as the spt7-1180 gcn5Δ and spt7-300 gcn5Δ double mutants have significantly more severe phenotypes than any of the single mutants (Table 2, compare spt8Δ, gcn5Δ, spt8Δ gcn5Δ, spt7-1180, spt7-1180 spt8Δ, spt7-1180 gcn5Δ, spt7-300, and spt7-300 gcn5Δ). Third, we tested the spt7-300 and the spt7-1180 mutations with respect to a previously described genetic interaction between spt8Δ and a mutation in another SAGA-encoding gene, SPT3. In this case, it was demonstrated that spt8Δ and the spt3-401 mutation mutually suppress each other with respect to their Spt− mutant phenotypes (12). Therefore, to test if the spt7-1180 and spt7-300 mutations act like spt8Δ, we constructed spt7-1180 spt3-401 and spt7-300 spt3-401 double mutants. As observed for spt8Δ, these spt7 mutations exhibited mutual suppression when in combination with spt3-401 (Table 3). Thus, we have shown by several genetic tests that the only role of the region defined by the spt7-300 and spt7-1180 deletions is to assemble or maintain Spt8 in the SAGA complex.

TABLE 3.

spt3-401 suppresses spt7-1180 and spt7-300 but not spt7-1125

| Genotype | Spt phenotypea |

|---|---|

| Wild type | + |

| spt3-401 | − |

| spt8Δ | − |

| spt7-1180 | − |

| spt7-300 | −/+ |

| spt7-1125 | − |

| spt3-401 spt8Δ | +/− |

| spt3-401 spt7-1180 | +/− |

| spt3-401 spt7-300 | +/− |

| spt3-401 spt7-1125 | − |

Phenotypes were determined by growing patches of cells on YEPD plates and then replica plating onto synthetic complete plates lacking histidine (SC-His) to assess suppression of his4-917δ (Spt− phenotype). Phenotypes are scored on a scale using +, +/−, −/+, and − (+, wild-type phenotype; −, the spt8Δ phenotype).

We also analyzed spt7-1125 and spt7-200 by an analogous set of double mutants to those described above for spt7-1180 and spt7-300. Mutant analysis of spt7-1125 and spt7-200 suggested that the region of Spt7 from amino acids 1125 to 1150 is required for a function unrelated to the association with Spt8. The results of the double mutant analysis showed that spt7-1125 behaves similarly to spt7-1180 with respect to interactions with spt8Δ and gcn5Δ (Table 2, spt7-1125, spt7-1125 spt8Δ, and spt7-1125 gcn5Δ). However, unlike spt7-1180, the Spt phenotype of spt7-1125 is not suppressed by spt3-401 (Table 3), supporting the idea that this deletion impairs Spt7 beyond losing its ability to interact with Spt8. The analysis of double mutants with spt7-200 was consistent with this hypothesis, as spt7-200 caused a mutant phenotype when in combination with spt8Δ (Table 2, spt7-200 and spt7-200 spt8Δ). The spt7-200 spt8Δ double mutant showed synthetic Ino−, Gal−, and Spt− phenotypes, similar to those of spt7-1125. Additionally, in a triple mutant, spt7-200 negated the suppression of spt8Δ by spt3-401 (data not shown). The phenotypes of the spt7-200 spt8Δ double mutant, then, are the same as the more severe phenotypes of spt7-1125 and are indicative of the loss of two distinct Spt7 functions. Taken together, these data support the existence of a function for the 1125 to 1150 region of Spt7.

Intragenic complementation by Spt7 amino- and carboxy-terminal deletions.

The deletion analysis of Spt7 described above demonstrated that the carboxy terminus is necessary for critical functions of the wild-type protein. To determine if this portion of the protein is sufficient for Spt7 function, we constructed a mutant lacking the first 873 codons of SPT7, spt7-100 (Fig. 4A). The design of this mutant was based on a previous observation that a cloned restriction fragment that encodes the carboxy-terminal fragment of Spt7 can partially complement an spt7Δ mutation (15). Indeed, the spt7-100 mutant is only partially defective with respect to several phenotypes caused by spt7 mutations, including growth, Spt, Gal, and Ino (Fig. 6A and data not shown). As the Spt7 carboxy terminus provides some, but not all, functions of the wild-type protein, we investigated if coexpression of two nonoverlapping portions of Spt7, using the spt7-100 (encoding amino acids 874 to 1132) and spt7-873 (encoding amino acids 1 to 873) mutations, might be able to complement. To do this test, a diploid strain containing spt7-100 and spt7-873 was constructed and its phenotypes were determined (Fig. 6A). The spt7-100/spt7-873 heterozygote exhibits phenotypes close to those of an SPT7+/SPT7+ strain, demonstrating intragenic complementation.

FIG. 6.

Analysis of intragenic complementation between spt7-100 and spt7-873. (A) Comparison of the phenotypes of wild-type (strain FY632), spt7Δ/spt7Δ (FY2065) spt7-100/spt7-100 (FY2063), spt7-873/spt7-873 (FY2064), and spt7-873/spt7-100 (FY2062) diploids. Cells were grown to saturation overnight in YEPD medium and spotted in a dilution series from 108 to 104 cells/ml, and the plates were incubated at 30°C for 2 days. (B) Western analysis of TAP-purified complexes from wild-type (FY2031), spt7-100 (FY2029), and spt7-873 (FY2042) haploids as well as spt7-873/spt7-100 (FY2062) heterozygous diploids. Purified complexes were run on SDS-PAGE (8% acrylamide) gels and probed using the HA (12CA5) antibody.

To determine whether the intragenic complementation arose from the partial function of two different mutant SAGA complexes or, alternatively, from the assembly of the two partial Spt7 products into a single SAGA complex, we purified SAGA from an spt7-100/spt7-873 heterozygote containing TAP-tagged Spt7-873. Silver staining showed that the complex from this strain appears similar to that from an spt7-873 mutant (data not shown). However, by Western analysis, we detected copurification of Spt7-100 with Spt7-873, suggesting the presence of both Spt7 truncations in one complex (Fig. 6B, lane 3). This evidence, along with the genetic complementation, indicates that the amino- and carboxy-terminal portions of Spt7 can be coassembled to form a largely functional SAGA complex.

Spt7 processing occurs in the carboxy terminus.

The SAGA complex has been shown to exist in an alternate form, referred to here as SLIK/SALSA (4, 18, 34; D. Sterner and S. Berger, personal communication). Characterization of SLIK/SALSA has shown that it differs from SAGA in at least two ways: it contains a smaller form of Spt7 and lacks Spt8 (4; Patrick Grant, personal communication). The smaller size of Spt7 in SLIK/SALSA suggests that it is proteolytically processed. To test this idea, full-length Spt7 was epitope tagged at both the amino and carboxy termini with HA and Myc tags, respectively. This doubly tagged version of Spt7 had wild-type function as determined by several phenotypic tests (data not shown). To examine the two forms of Spt7, whole-cell extracts were fractionated on a Mono Q column, previously shown to separate SAGA and SLIK/SALSA (4), and fractions were assayed for each Spt7 epitope tag by Western analysis (Fig. 7). Our results demonstrate that the smaller form of Spt7 can be detected with the antibody against the amino-terminal HA epitope tag but not with the antibody against the carboxy-terminal Myc epitope tag (Fig. 7, top, fractions 34 and 36). These results strongly suggest that the smaller form of Spt7 arises from the removal of part of its carboxy terminus. Confirmation of this result was obtained by probing whole-cell extracts with the HA and Myc antibodies (Fig. 8, upper panels). Consistent with results from the Mono Q fractionation, both forms of Spt7 are detectable with the antibody against the amino-terminal HA epitope, while only the longer form is detectable with the antibody against the carboxy-terminal Myc epitope. Moreover, a processed piece of Spt7 with a molecular mass of approximately 40 kDa containing the Myc epitope can be observed by Western blotting (Fig. 8, lower panel). These results indicate that Spt7 processing occurs in the carboxy terminus and is unlikely to be an artifact of fractionation, because it is observed out of whole-cell extracts.

FIG. 7.

Spt7 in SLIK/SALSA lacks part of the carboxy terminus. Mono Q fractionation of yeast whole-cell extract from wild-type (strain FY2025), spt7-200 (FY2045), and spt7-300 (FY2046) strains expressing HA- and Myc-tagged Spt7. Western analyses of Mono Q fractions were probed with antibodies to HA or Myc (to detect Spt7) as well as antibodies to Ada1. The diagram depicts the doubly-tagged Spt7 protein; Spt7-200 lacks the region in black, and Spt7-300 lacks the region in gray. The faster-migrating band in the panel showing the anti-HA antibody-probed blot of Mono Q fractions from a wild-type strain represents the carboxy-terminally processed form of Spt7. The presence of Ada1 in the fractions containing SLIK/SALSA in the spt7-200 panel is likely due to the loss of Spt8 from SAGA upon fractionation.

FIG. 8.

Analysis of yeast whole-cell extract from untagged and tagged wild-type (strain FY2025), spt7-200 (FY2045), spt7-300 (Y2046), and spt8Δ (FY2038) strains on Western blots probed with HA (12CA5) or Myc (A14) antibodies. Equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane.

To map the region of Spt7 involved in this processing event, several spt7 deletion mutants described in a previous section were analyzed. Extracts from spt7-1180 and spt7-1125 strains were fractionated on a Mono Q column and Western blotted. The Spt7-1180 protein was processed while Spt7-1125 protein was not (data not shown), suggesting that amino acids 1125 to 1180 of Spt7 are required for the processing to occur. To delineate further the region involved in processing, we examined the two spt7 internal deletion mutants that are missing either amino acids 1125 to 1150 (in spt7-200) or 1150 to 1180 (in spt7-300). The spt7-200 mutation greatly impairs Spt7 processing, as there are barely detectable levels of the shorter form of Spt7 in this mutant (Fig. 7 and 8). In contrast, the spt7-300 mutation causes no detectable effect on processing (Fig. 7 and 8). Similar to an spt8Δ mutant, the spt7-300 mutant has an altered elution profile on a Mono Q column. These results demonstrate that adjacent regions of Spt7, as defined by spt7-200 and spt7-300, are required independently for Spt7 processing and for association with Spt8, respectively. Furthermore, they show that Spt8 is not required for Spt7 processing, a conclusion confirmed by the presence of processed Spt7 in an spt8 deletion mutant (Fig. 8, lane 5). Finally, the results from the Mono Q fractionation show that the spt7-200 mutant has severely reduced levels of SLIK/SALSA, using Ada1 as a marker for the presence of both SAGA and SLIK/SALSA. The low level of Ada1 in the characteristic SLIK/SALSA fractions may actually be due to SAGA that has lost Spt8 during fractionation, since we see the larger form of Spt7 in those fractions both wild-type and spt7-200 strains as well.

Nonprocessed Spt7 mutant has normal transcriptional activation of HIS3 and TRP3.

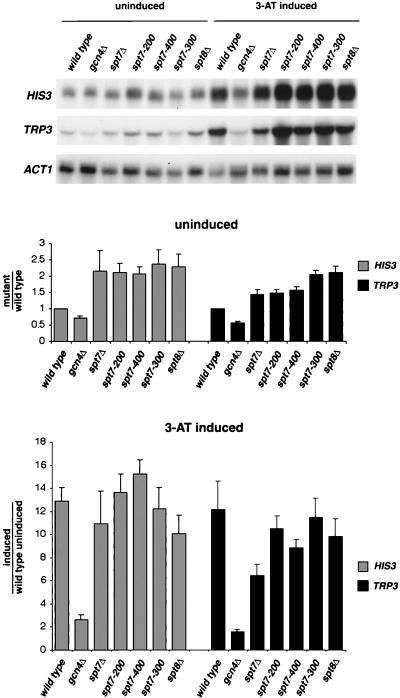

The identification of a nonprocessed form of Spt7 allowed us to examine the requirement for SLIK/SALSA in vivo. Previous studies showed that, under conditions of amino acid starvation, SLIK/SALSA is a predominant form of SAGA-related complexes (4). This finding raised the possibility that SLIK/SALSA is required for activation of genes under general amino acid control. We tested the requirement for SLIK/SALSA under these conditions by measuring the level of HIS3 and TRP3 mRNAs in the spt7-200 mutant, where SLIK/SALSA levels are severely reduced. Our results (Fig. 9) show that there is no significant effect on activated levels of HIS3 or TRP3 mRNAs in the spt7-200 mutant. In addition, the level of these transcripts is normal in the spt7 mutants that have lost interaction with Spt8. These results strongly suggest that SLIK/SALSA is not necessary for activation of HIS3 or TRP3 and may not be required in general for activation via the general amino acid control pathway.

FIG. 9.

Northern analysis of spt7 internal deletion mutants. Wild-type (strain FY3), gcn4Δ (FY971), spt7Δ (FY2028), spt7-200 (FY2047), spt7-300 (FY2048), spt7-400 (FY2049), and spt8Δ (FY2039) mutants were grown in SC-His to approximately 1 × 107 to 2 × 107 cells/ml and induced with 40 mM 3-aminotriazole for 2 h. RNA was then made from uninduced and induced samples. Northern blots were probed separately with HIS3, TRP3, and ACT1 DNA probes. Shown is a representative Northern blot. The bar graphs below the Northern blot show the average and standard error measured for each mRNA level, with the wild-type, uninduced level equal to 1.0. Each value was determined three to six times.

Previous studies also showed that spt8Δ and spt3Δ mutations cause increased levels of basal transcription of TRP3 and HIS3, suggesting a possible role for SAGA in controlling the uninduced levels of mRNAs of these genes (4). Northern analysis (Fig. 9) shows that there is an approximately twofold increase in the uninduced levels of HIS3 and TRP3 mRNAs in all of the spt7 mutants, including spt7-200, in which Spt7 processing does not occur and spt7-300, which does not associate with Spt8. As previously shown (4), an spt8Δ mutation also causes an approximately twofold increase in HIS3 and TRP3 mRNA levels. These results suggest that perturbations to the level of SAGA and/or SLIK/SALSA cause mild defects in this aspect of transcriptional control.

DISCUSSION

Our studies have investigated the functions of Spt7, a core component of the S. cerevisiae SAGA coactivator complex. These results have strongly suggested that Spt7 plays an important role in SAGA assembly and have demonstrated that partial SAGA complexes that contain Spt7 can be formed in the absence of the core subunits Ada1 and Spt20. Deletion analysis has delineated a minimal functional Spt7 that encompasses the carboxy-terminal portion of the protein. Further analyses have established that one carboxy-terminal region of Spt7 is required for interaction with Spt8, and an adjacent small region is required for Spt7 carboxy-terminal processing. We have shown that this carboxy-terminally processed Spt7 is the form previously described to be in SLIK/SALSA, an altered version of SAGA (4, 18). An spt7 mutant that impairs Spt7 processing has only weak mutant phenotypes, suggesting that processed Spt7 and the SLIK/SALSA complex are not strongly required under the conditions tested.

Spt7 and SAGA complex formation.

Previous biochemical and genetic studies showed that Spt7, Spt20, and Ada1 are required for integrity of the SAGA complex. Our studies have shown that Spt7 must play an early and central role in SAGA formation as it is necessary for normal levels of Spt20 and Ada1. In addition, Spt7, Spt20, and Ada1 are each required for the presence of other SAGA components in the complex. Thus, directly or indirectly, Spt7 is required for the presence of most SAGA subunits. These results strongly suggest that one of the first steps in SAGA assembly is the association of the three core subunits, Spt7, Spt20, and Ada1. In addition, the key role for Spt7 in modulating the level of other SAGA subunits raises the possibility that the level of SAGA is regulated under some conditions by controlling the level of Spt7. Recent work shows that SPT7 mRNA levels are decreased in cells treated with rapamycin or shifted to low quality nitrogen or carbon sources, suggesting regulation by the Tor pathway (36). Another study demonstrated that Spt7 is ubiquitinated, indicating a possible mechanism to control Spt7 levels (33).

Several results suggest that different regions of Spt7 play distinct roles in SAGA assembly and function. Our studies have shown that Spt7 associates with several SAGA members in the absence of Spt20 and Ada1, including Spt8, Taf6, Taf9, and Taf10. Previous results demonstrated that the histone fold region of Spt7 interacts with Taf10 (13). Our results, discussed below, show that a different region is required for the association between Spt7 and Spt8. Furthermore, we have observed intragenic complementation between nonoverlapping spt7 deletions, strongly suggesting that the two different pieces of Spt7 expressed in the heterozygote play independent roles in SAGA assembly and/or function.

Spt7-Spt8 interaction.

Our analysis has shown that Spt8 requires a region in the carboxy terminus of Spt7 for assembly into SAGA. Two results suggest that the Spt7-Spt8 interaction is direct. First, two spt7 deletions, spt7-300 and spt7-1180, cause loss of Spt8 from SAGA without the detectable loss of any other SAGA components. Second, Spt8 is still associated with Spt7 in an spt20Δ ada1Δ double mutant. In addition, the two spt7 deletions that cause the loss of Spt8 from SAGA result in the same set of mutant phenotypes as does an spt8Δ mutation, strongly suggesting that the only function of this carboxy-terminal region of Spt7 is for association with Spt8. The extremely similar mutant phenotypes displayed by spt8Δ, spt7-1180, and spt7-300 strongly suggest that Spt8 functions in vivo solely through its presence in SAGA.

The SAGA complex has been divided into distinct functional subgroups based on both genetic and biochemical results (27, 32). One subgroup contains Spt8 and Spt3, as several studies have suggested that these factors play related roles in transcription initiation by controlling the binding of TBP to TATA regions (22). However, previous studies showed that their physical association in SAGA is independent: Spt8 is still present in SAGA purified from an spt3Δ mutant and Spt3 is still present in SAGA from an spt8Δ mutant (38). Our results have confirmed this finding and have provided additional information on the independent association of these two factors within SAGA. While Spt8's association with SAGA is dependent upon Spt7, the presence of Spt3 in SAGA is dependent upon Spt20 and Ada1. In spite of these distinct associations, Spt8 and Spt3 may still interact directly in the assembled complex.

Analysis of in vivo requirement for Spt7 processing.

Several studies have provided strong evidence for multiple forms of SAGA (4, 18, 34). One form of SAGA previously described, named SLIK or SALSA, was defined as having an altered form of Spt7 and lacking Spt8 (4; Patrick Grant, personal communication). Our analysis of Spt7 has provided a view of how this form of SAGA arises. First, analysis of wild-type Spt7 showed that this altered form of Spt7 lacks a portion of its carboxy-terminal end. In addition, the spt7-200 mutant identified a region of Spt7 required for the presence of this altered form, suggesting that it arises by cleavage within or very near amino acids 1125 to 1150. Since this region is immediately amino terminal to the region of Spt7 required for the association of Spt8 with Spt7, the cleavage of Spt7 would result both in generating the shorter form of Spt7 and the loss of Spt8. Analysis of an spt8Δ mutant demonstrated that Spt8 is not required for Spt7 processing.

Since the spt7-200 mutation blocks the carboxy-terminal processing of Spt7, resulting in little or no SLIK/SALSA complex in vivo, we were able to address the requirement for this form of SAGA in vivo. As described in Results, spt7-200 causes only a few weak mutant phenotypes. While these mild defects are likely caused by the loss of Spt7 processing, we cannot rule out the possibility that the spt7-200 deletion impairs Spt7 independently of the processing defect. In an spt7-200 mutant, activation of transcription of the HIS3 and TRP3 genes was normal, strongly suggesting that SLIK/SALSA plays no significant role in the activation of genes regulated by general amino acid control. Since a previous study suggests that SLIK/SALSA is the major form of SAGA in cells induced with 3-AT, SLIK/SALSA and SAGA may be functionally equivalent under most conditions. We cannot rule out that there may be defects in gene expression that we did not detect. We also cannot rule out the possibility that SLIK/SALSA function is actually dependent upon something other than the processing of Spt7 and loss of Spt8. Regardless of these uncertainties, a significant role for SLIK/SALSA in vivo remains to be discovered.

Conservation of Spt7.

Several SAGA components have been shown to be conserved and to exist in similar mammalian complexes (6, 25, 26, 28, 46). With respect to the three SAGA core components, mammalian homologues of Spt7 and Ada1 have been recently identified (26), while no mammalian homologue of Spt20 has yet been reported. Comparison of the sequences of human and S. cerevisiae Spt7 reveals that the human version, named STAF65γ, is considerably smaller (414 amino acids) than S. cerevisiae Spt7 (1332 amino acids). Interestingly, STAF65γ is homologous to the carboxy-terminal 543 amino acids of S. cerevisiae Spt7, including the previously identified histone fold motif (13) and the region of Spt7 required for processing. This conservation corresponds extremely well with our finding that expression of the carboxy-terminal 459 amino acids of Spt7 can complement many spt7Δ mutant phentoypes. In mammalian cells, the functions provided by the amino terminus of Spt7 in S. cerevisiae may not be required or may be encoded by another gene.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joe Martens and Erica Larschan for helpful comments on the manuscript and members of the Winston laboratory for stimulating discussions. We are grateful to Shelley Berger, David Sterner, and Patrick Grant for sharing unpublished data. We thank Jerry Workman and Shigehiro Osada for their hospitality and invaluable aid with SAGA purification techniques. We thank Shelley Berger, Michael Green, Lenny Guarente, Jerry Workman, and Patrick Grant for providing antibodies to SAGA subunits. We also thank Bertrand Séraphin for plasmids.

P.-Y.W. was supported by a Predoctoral Fellowship from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM45720 to F.W.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1988. Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene Publishing Associates/Wiley-Interscience, New York, N.Y.

- 2.Balasubramanian, R., M. G. Pray-Grant, W. Selleck, P. A. Grant, and S. Tan. 2001. Role of the Ada2 and Ada3 transcriptional coactivators in histone acetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:7989-7995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baudin, A., O. Ozier-Kalogeropoulos, A. Denouel, F. Lacroute, and C. Cullin. 1993. A simple and efficient method for direct gene deletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:3329-3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belotserkovskaya, R., D. E. Sterner, M. Deng, M. H. Sayre, P. M. Lieberman, and S. L. Berger. 2000. Inhibition of TATA-binding protein function by SAGA subunits Spt3 and Spt8 at Gcn4-activated promoters. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:634-647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhaumik, S. R., and M. R. Green. 2001. SAGA is an essential in vivo target of the yeast acidic activator Gal4p. Genes Dev. 15:1935-1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brand, M., K. Yamamoto, A. Staub, and L. Tora. 1999. Identification of TATA-binding protein-free TAFII-containing complex subunits suggests a role in nucleosome acetylation and signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 274:18285-18289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, C. E., L. Howe, K. Sousa, S. C. Alley, M. J. Carrozza, S. Tan, and J. L. Workman. 2001. Recruitment of HAT complexes by direct activator interactions with the ATM-related Tra1 subunit. Science 292:2333-2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brownell, J. E., J. Zhou, T. Ranalli, R. Kobayashi, D. G. Edmondson, S. Y. Roth, and C. D. Allis. 1996. Tetrahymena histone acetyltransferase A: a homolog to yeast Gcn5p linking histone acetylation to gene activation. Cell 84:843-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dudley, A. M., C. Rougeulle, and F. Winston. 1999. The Spt components of SAGA facilitate TBP binding to a promoter at a post-activator-binding step in vivo. Genes Dev. 13:2940-2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eberharter, A., S. John, P. A. Grant, R. T. Utley, and J. L. Workman. 1998. Identification and analysis of yeast nucleosomal histone acetyltransferase complexes. Methods 15:315-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenmann, D. M., K. M. Arndt, S. L. Ricupero, J. W. Rooney, and F. Winston. 1992. SPT3 interacts with TFIID to allow normal transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 6:1319-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenmann, D. M., C. Chapon, S. M. Roberts, C. Dollard, and F. Winston. 1994. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SPT8 gene encodes a very acidic protein that is functionally related to SPT3 and TATA-binding protein. Genetics 137:647-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gangloff, Y. G., S. L. Sanders, C. Romier, D. Kirschner, P. A. Weil, L. Tora, and I. Davidson. 2001. Histone folds mediate selective heterodimerization of yeast TAF(II)25 with TFIID components yTAF(II)47 and yTAF(II)65 and with SAGA component ySPT7. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1841-1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gangloff, Y. G., S. Werten, C. Romier, L. Carre, O. Poch, D. Moras, and I. Davidson. 2000. The human TFIID components TAF(II)135 and TAF(II)20 and the yeast SAGA components ADA1 and TAF(II)68 heterodimerize to form histone-like pairs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:340-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gansheroff, L. J., C. Dollard, P. Tan, and F. Winston. 1995. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SPT7 gene encodes a very acidic protein important for transcription in vivo. Genetics 139:523-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant, P. A., L. Duggan, J. Cote, S. M. Roberts, J. E. Brownell, R. Candau, R. Ohba, T. Owen-Hughes, C. D. Allis, F. Winston, S. L. Berger, and J. L. Workman. 1997. Yeast Gcn5 functions in two multisubunit complexes to acetylate nucleosomal histones: characterization of an Ada complex and the SAGA (Spt/Ada) complex. Genes Dev. 11:1640-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant, P. A., D. Schieltz, M. G. Pray-Grant, D. J. Steger, J. C. Reese, J. R. Yates III, and J. L. Workman. 1998. A subset of TAF(II)s are integral components of the SAGA complex required for nucleosome acetylation and transcriptional stimulation. Cell 94:45-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant, P. A., D. Schieltz, M. G. Pray-Grant, J. R. Yates III, and J. L. Workman. 1998. The ATM-related cofactor Tra1 is a component of the purified SAGA complex. Mol. Cell 2:863-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall, M. N., L. Hereford, and I. Herskowitz. 1984. Targeting of E. coli beta-galactosidase to the nucleus in yeast. Cell 36:1057-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haynes, S. R., C. Dollard, F. Winston, S. Beck, J. Trowsdale, and I. B. Dawid. 1992. The bromodomain: a conserved sequence found in human, Drosophila and yeast proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horiuchi, J., N. Silverman, B. Pina, G. A. Marcus, and L. Guarente. 1997. ADA1, a novel component of the ADA/GCN5 complex, has broader effects than GCN5, ADA2, or ADA3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:3220-3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larschan, E., and F. Winston. 2001. The S. cerevisiae SAGA complex functions in vivo as a coactivator for transcriptional activation by Gal4. Genes Dev. 15:1946-1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, T. I., H. C. Causton, F. C. Holstege, W. C. Shen, N. Hannett, E. G. Jennings, F. Winston, M. R. Green, and R. A. Young. 2000. Redundant roles for the TFIID and SAGA complexes in global transcription. Nature 405:701-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorenz, M. C., R. S. Muir, E. Lim, J. McElver, S. C. Weber, and J. Heitman. 1995. Gene disruption with PCR products in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 158:113-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez, E., T. K. Kundu, J. Fu, and R. G. Roeder. 1998. A human SPT3-TAFII31-GCN5-L acetylase complex distinct from transcription factor IID. J. Biol. Chem. 273:23781-23785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez, E., V. B. Palhan, A. Tjernberg, E. S. Lymar, A. M. Gamper, T. K. Kundu, B. T. Chait, and R. G. Roeder. 2001. Human STAGA complex is a chromatin-acetylating transcription coactivator that interacts with pre-mRNA splicing and DNA damage-binding factors in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:6782-6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narlikar, G. J., H.-Y. Fan, and R. E. Kingston. 2002. Cooperation between complexes that regulate chromatin structure and transcription. Cell 108:475-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogryzko, V. V., T. Kotani, X. Zhang, R. L. Schiltz, T. Howard, X. J. Yang, B. H. Howard, J. Qin, and Y. Nakatani. 1998. Histone-like TAFs within the PCAF histone acetylase complex. Cell 94:35-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rigaut, G., A. Shevchenko, B. Rutz, M. Wilm, M. Mann, and B. Seraphin. 1999. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat. Biotechnol. 17:1030-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts, S. M., and F. Winston. 1997. Essential functional interactions of SAGA, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae complex of Spt, Ada, and Gcn5 proteins, with the Snf/Swi and Srb/mediator complexes. Genetics 147:451-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rose, M. D., F. Winston, and P. Hieter. 1990. Methods in yeast genetics: a laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 32.Roth, S. Y., J. M. Denu, and C. D. Allis. 2001. Histone acetyltransferases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:81-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saleh, A., M. Collart, J. A. Martens, J. Genereaux, S. Allard, J. Cote, and C. J. Brandl. 1998. TOM1p, a yeast hect-domain protein which mediates transcriptional regulation through the ADA/SAGA coactivator complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 282:933-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saleh, A., V. Lang, R. Cook, and C. J. Brandl. 1997. Identification of native complexes containing the yeast coactivator/repressor proteins NGG1/ADA3 and ADA2. J. Biol. Chem. 272:5571-5578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneider, B. L., W. Seufert, B. Steiner, Q. H. Yang, and A. B. Futcher. 1995. Use of polymerase chain reaction epitope tagging for protein tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 11:1265-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shamji, A. F., F. G. Kuruvilla, and S. L. Schreiber. 2000. Partitioning the transcriptional program induced by rapamycin among the effectors of the Tor proteins. Curr. Biol. 10:1574-1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122:19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sterner, D. E., P. A. Grant, S. M. Roberts, L. J. Duggan, R. Belotserkovskaya, L. A. Pacella, F. Winston, J. L. Workman, and S. L. Berger. 1999. Functional organization of the yeast SAGA complex: distinct components involved in structural integrity, nucleosome acetylation, and TATA-binding protein interaction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:86-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sterner, D. E., X. Wang, M. H. Bloom, and S. L. Berger. 2002. The SANT domain of Ada2 is required for normal acetylation of histones by the yeast SAGA complex. J. Biol. Chem. 277:8178-8186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swanson, M. S., E. A. Malone, and F. Winston. 1991. SPT5, an essential gene important for normal transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, encodes an acidic nuclear protein with a carboxy-terminal repeat. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:3009-3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40a.Swanson, M. S., and F. Winston. 1992. SPT4, SPT5 and SPT6 interactions: effects on transcription and viability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 132:325-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tora, L. 2002. A unified nomenclature for TATA box binding protein (TBP)-associated factors (TAFs) involved in RNA polymerase II transcription. Genes Dev. 16:673-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Utley, R. T., K. Ikeda, P. A. Grant, J. Cote, D. J. Steger, A. Eberharter, S. John, and J. L. Workman. 1998. Transcriptional activators direct histone acetyltransferase complexes to nucleosomes. Nature 394:498-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vignali, M., D. J. Steger, K. E. Neely, and J. L. Workman. 2000. Distribution of acetylated histones resulting from Gal4-VP16 recruitment of SAGA and NuA4 complexes. EMBO J. 19:2629-2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winston, F., and C. D. Allis. 1999. The bromodomain: a chromatin-targeting module? Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:601-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winston, F., C. Dollard, and S. L. Ricupero-Hovasse. 1995. Construction of a set of convenient Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that are isogenic to S288C. Yeast 11:53-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu, J., J. M. Madison, S. Mundlos, F. Winston, and B. R. Olsen. 1998. Characterization of a human homologue of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae transcription factor spt3 (SUPT3H). Genomics 53:90-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]