Abstract

R-Ras3/M-Ras is a novel member of the Ras subfamily of GTP-binding proteins which has a unique expression pattern highly restricted to the mammalian central nervous system. In situ hybridization using an R-Ras3 cRNA probe revealed high levels of R-Ras3 transcripts in the hippocampal region of the mouse brain as well as a pattern of expression in the cerebellum that was distinct from that of H-Ras. We found that R-Ras3 was activated by nerve growth factor (NGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor as well as by the guanine nucleotide exchange factor GRP but not by epidermal growth factor. Ectopic expression of either R-Ras3 or GRP in PC12 cells induced efficient neuronal differentiation. The ability of NGF as well as GRP to promote differentiation of PC12 cells was attenuated by an R-Ras3 dominant-negative mutant. Furthermore, the biological action of R-Ras3 in PC12 cells was dependent on the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). Interestingly, whereas R-Ras3 was unable to mediate efficient activation of MAPK activity in NIH 3T3 cells, it was able to do so in PC12 cells. This cell-type specificity is in stark contrast to that of H-Ras, which can stimulate the MAPK pathway in both cell types. Indeed, this pattern of MAPK activation could be explained by the fact that R-Ras3 was unable to activate c-Raf, while it bound and stimulated the neuronal Raf isoform, B-Raf, in PC12 cells. Thus, R-Ras3 is implicated in a novel pathway of neuronal differentiation by coupling specific trophic factors to the MAPK cascade through the activation of B-Raf.

Members of the Ras subfamily of GTP-binding proteins are membrane-bound intracellular signaling molecules that mediate a wide variety of cellular functions, including proliferation, survival, and differentiation (1, 6). The Ras subfamily consists of at least 15 highly conserved proteins, including H-Ras, N-Ras, K-Ras, R-Ras, TC21, Rap1A, Rheb, RalA, and more recently, R-Ras3 (4). Several of these Ras-related genes have been shown to possess the ability to transform immortalized rodent fibroblasts in culture, and Ras itself has been found to be mutated in over 15% of all human tumors (5).

Recently, it has become clear that the Ras-related proteins possess distinct biochemical and biological activities not ascribed to the prototypic ras oncogenes. R-Ras has been shown to promote cell adhesion through the activation of specific integrins on the cell surface (45). This is in contrast to Ras oncogene-expressing cells, which are generally less adhesive to components of the extracellular matrix due to the downregulation of certain subtypes of integrins (35). Additionally, Rap1A, another Ras-related protein, has been shown to inhibit Ras transformation in fibroblasts (14). However, in other cell types, such as PC12 cells, both genes appear to promote neurite outgrowth (44). Further evidence of the importance of the Ras-related proteins can be inferred from the results of studies of Ras knockout mice. Targeted gene disruptions in mice of all three Ras isoforms have been made, with neither H- or N-ras displaying any detectable phenotype as a result (41). K-ras null mice, however, exhibited effects that were embryonically lethal, with defects in early embryonic hematopoiesis (18). Thus, it is possible that the three Ras isoforms may share overlapping functions during development. Alternatively, several of the Ras-related proteins may act independently or in concert with the prototypic Ras in transducing extracellular signals in various tissues.

Ras proteins act as molecular switches, alternating from an inactive GDP-bound state to an active GTP-bound state. Proteins known as guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) catalyze the release of GDP, and the large intracellular molar excess of GTP ensures its preferential uptake by GTPases (3). Several Ras GEFs have been identified, including Sos, GRF, GRF2, and RasGRP (hereafter referred to as GRP) (7, 10, 12, 13). GRF and GRP are particularly interesting, because their expression is highly enriched in the central nervous system (CNS) (10, 13).

We and others have previously described the cloning of R-Ras3 (also referred to as M-Ras), a novel member of the Ras-related proteins (11, 19, 26, 29, 36). Interestingly, in contrast to the other members of the Ras subfamily, R-Ras3 is not ubiquitously expressed and its expression is highly restricted to the mammalian CNS (19). Additionally, unlike H-Ras, R-Ras3 does not mediate efficient activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in mouse fibroblasts (19, 20). We and others have further shown that R-Ras3 preferentially activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) pathway to a greater degree than does H-Ras (20). In fact, R-Ras3 forms a complex with the p110 catalytic subunit of PI3-K in a GTP-dependent fashion, with an apparently higher affinity than H-Ras (20).

Multiple signaling pathways have been implicated in neuronal survival and differentiation. For example, PI3-K, through the generation of lipid second messengers, leads to the activation of the serine/threonine kinase Akt/PKB (8). Activation of Akt promotes the survival of a variety of neuronal cell types, including the PC12 cell line, which has been extensively used as a model for neuronal survival (8). Consistent with this finding, we have previously reported that R-Ras3 activates Akt in PC12 cells and promotes cell survival upon the removal of nerve growth factor (NGF) in a PI3-K-dependent manner (20). As for neuronal differentiation, it has been demonstrated that PI3-K is necessary for the neurite outgrowth of PC12 cells (21). In addition, the MAPK pathway has also been shown to be critical for neuronal differentiation. However, the effect of MAPK activation in these cells is quite complex, with differing responses observed depending on the duration of its activation. For instance, in PC12 cells, a transient activation of MAPK by epidermal growth factor (EGF) results in cell proliferation, whereas a sustained activation by NGF leads to cell cycle withdrawal and differentiation (28).

While the study of Ras-related genes has produced a great deal of information as to their possible functions, less is known with respect to their upstream regulation. Additionally, the role of these proteins in certain cellular functions, such as neuronal differentiation, has not been clearly addressed. Due to the fact that R-Ras3 expression is highly restricted to the CNS, as well as that none of the knockout mice of the three Ras isoforms displayed any neurological defects, it is likely that R-Ras3 serves as a key mediator of signaling in cells of neural origin. In the present report, we demonstrate that R-Ras3 has an expression pattern in the CNS that is distinct from that of H-Ras. In addition, we show that expression of R-Ras3 causes striking differentiation in the PC12 system. We have further explored the role of upstream signaling events leading to R-Ras3 activation and have shown that a dominant-negative mutant of R-Ras3 blocks NGF-induced differentiation in PC12 cells. Finally, the downstream signaling pathways mediating R-Ras3-induced differentiation have also been investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

The NIH 3T3 cell line was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% calf serum (CS). The human embryonic kidney 293T cell line was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal CS (FCS). PC12 cells were propagated on poly-d-lysine coated dishes in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% horse serum and 5% FCS.

Plasmids.

The construction of the wild-type (WT) and constitutively active R-Ras3 mutant R-Ras3 L71 has previously been described (19). Both cDNAs were subsequently amplified by the PCR and cloned into the pCEFL KZ AU5 vector containing an EF1α promoter and an AU5 epitope tag fused in frame at the 5′ end. The R-Ras3 dominant negative (pCEFL KZ AU5 R-Ras3 N27) was generated by a PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis strategy. The construction of the oncogenic form of H-Ras (H-Ras R12) in the pCEFL KZ AU5 vector has been described previously (34). The WT H-Ras construct was generated by PCR amplification of the coding region and was subsequent subcloned into the pCEFL KZ AU5 vector. The Ras-binding domain (RBD) of p110 α (amino acids [aa] 127 to 314) was cloned in frame in the prokaryotic expression vector pGEX-KG. For experiments using various dominant inhibitory molecules, all cDNAs were cloned into the expression vector pCEV29-CAT or pCDNA3. These include dominant-negative mutants of MEK (MEKA) and PI3-K (p85ΔiSH2-N). The neurofilament light chain (NF-L) promoter luciferase plasmid was a generous gift from Lynn Heasley (University of Colorado Health Sciences Center). The GRP constructs (RBC7HA and GRPΔDAG) in the pBabe puro vector were kindly provided by James Stone (University of Alberta) and have been described elsewhere (10). The pCA-GAP-EGFP expression plasmid was a gift from A. Okada (Stanford University), and details of this construct have been reported previously (33).

Antibodies.

The anti-R-Ras3 rabbit polyclonal antibody has been described previously (20). The anti-hemagglutinin (anti-HA) and the anti-Ras antibodies were obtained from the Monoclonal Core Facility of The Mount Sinai School of Medicine. All other antibody reagents were purchased from commercial sources: anti-AU5 monoclonal antibody from Covance, anti-GAP-43 antibody from Calbiochem, anti-phospho p44/p42 extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1 and ERK2 E10 monoclonal antibody from Cell Signaling, and anti-c-Raf-1 (C-20) polyclonal antibody, anti-Raf-B (C-19) polyclonal antibody, and anti-ERK2 (C-14) polyclonal antibody from Santa Cruz.

In situ hybridization.

In situ hybridization was performed on frozen tissue sections using antisense cRNA probes. Transcripts were labeled using [35S]UTP as described previously (30). [35S]-labeled probes were used at a concentration of 20 ng/ml in hybridization buffer (50% deionized formamide, 0.6 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Ficoll, 0.05% bovine serum albumin, 0.05% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 10% dextran sulfate, 0.1 mg of salmon sperm DNA/ml, 50 μg of yeast tRNA/ml, 1.0 mg of Saccharomyces cerevisiae total RNA/ml). Tissue sections were hybridized at 50°C for 16 to 18 h and then washed under high stringency conditions (1× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 50% formamide, 10 mM dithiothreitol) at 50°C, followed by a room temperature wash with 0.5× SSC. Nonhybridized probe was digested with 20 μg of RNase A/ml for 30 min at room temperature. Next, slides were rinsed in RNase-free water and allowed to dry. Sections were dipped in NTB-2 emulsion (Eastman Kodak) diluted 1:1 in H2O, air dried, and stored desiccated at 4°C. After appropriate exposure times, slides were developed in Kodak D-19 developer and counterstained with hematoxylin.

Transcript analysis.

Around 10 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA by murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Inc.). Approximately 3 μl of cDNA was subjected to PCR using primer pairs specific for either mouse (+, caacaggttccagagaaaaccag; −, agtcatcctgggttcctcgctgc) or rat (+, atggcgaccagcgctgttcccagtgac; −, tcacaagatgacacactgtagtt) sequences. The amplification conditions used were 94°C for 1 min, 59°C for 1.5 min, and 72°C for 2 min for 30 cycles. Amplified products were first resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel and then transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane, and their authenticity was confirmed by hybridizing filters with a full-length rat R-Ras3 cDNA probe. Standard Northern blot analysis was performed using 10 μg of total RNA, and membranes were hybridized with a rat R-Ras3 cDNA probe. The final stringency wash was carried out at 55°C in 0.1× SSC-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and blots were then exposed to X-ray films at −70°C.

In vivo activation of R-Ras3.

A total of 5 × 105 293T cells were transfected with 1 μg of pCEFL KZ AU5 R-Ras3 WT along with 10 μg of either GRP or empty vector by a standard calcium phosphate precipitation method. Around 18 h after transfection, cells were placed in low serum (0.3% FCS) for 20 h and subsequently solubilized in 500 μl of lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM polymethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 2 mM leupeptin, 2 mM aprotinin). For a typical assay, approximately 20 μg of bacterially derived recombinant glutathione transferase (GST)-p110 RBD was first coupled to 30 μl of glutathione Sepharose (Molecular Probes). Next, 500 μg of total cell extracts prepared from 293T transfectants was added and allowed to incubate for 2 h at 4°C. Beads were washed three times in lysis buffer and boiled in Laemmli buffer. Western blot analyses were performed to detect the amount of R-Ras3 protein bound to GST-p110 RBD with the anti-AU5 monoclonal antibody. Similar assays were performed in PC12 cells, with the exception that for trophic factor triggering, 10 μg of R-Ras3 WT was transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Inc.). Cultures were then placed in 1.0% serum for 20 h and exposed to NGF (100 ng/ml), phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) (100 nM), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (20 ng/ml), and EGF (20 ng/ml) for 5 min. For other assays, PC12 cells were cotransfected with 5 μg of R-Ras3 WT and 10 μg of either GRP or a control vector. The subsequent processing was performed as described above for 293T cells. Similar pull-down assays were performed to monitor H-Ras GTP loading, except that a GST-Raf RBD probe was used instead.

Ras GTP-loading assays.

Ras-GTP levels were measured by metabolic labeling of cells with 0.2 mCi of [32P]orthophosphate (23)/ml. Cells were solubilized in a buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 20 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 10 mM Na3VO4, 50 mM NaF, 20 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 40 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 μg each of aprotinin and leupeptin/ml, and 1 mM PMSF. The Ras protein was immunoprecipitated with 5.0 μg of Y259 antibody in the presence of a rabbit anti-rat secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) and 60 μl of (γ-bind) G Sepharose beads (Pharmacia) at 4°C for 2 h. Radiolabeled guanine nucleotides were then eluted by heating at 70°C for 3 min in 20 μl of elution buffer (1 M KH2PO4, 5 mM EDTA). Thin-layer chromatography was performed by spotting 3,000 cpm of each sample onto a cellulose plate (cellulose PEI-F; Baker-flex [J. T. Baker]) using 1 M KH2PO4 (pH 3.5) as the mobile phase. The plate was then dried, and autoradiography was performed at −70°C for 12 to 24 h. Results were quantified by an imaging densitometer (Bio-Rad).

PC12 differentiation assays.

Differentiation of PC12 cells was determined by two methods. For morphology-based assays, cells were transfected with 2 μg of pCEFL KZ AU5 R-Ras3 L71 and 0.2 μg of a GFP plasmid. Approximately 48 h after transfection, cells were visualized under fluorescence microscopy and GFP-positive cells were scored for the presence of neurites longer than two cell diameters. Alternatively, for transcriptional reporter assays, PC12 cells were transfected using lipofectamine or Lipofectamine 2000 with 1 μg of the NF-L promoter reporter plasmid and 0.1 μg or 0.3 μg of pCEFL KZ AU5 R-Ras L71 or a control plasmid, respectively. Approximately 48 h after transfection, cells were solubilized in 150 μl of the supplied lysis buffer (Promega) and 20-μl aliquots of the lysate were used to measure luciferase activity according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega) by using a luminometer (Turner). All values were normalized to total cell protein and are represented as fold increase over control. To investigate the involvement of the MAPK and PI3-K pathways, pharmacological inhibitors (PD90859 [50 μM] and LY294002 [10 μM]) were added 24 h after transfection and fresh inhibitor-containing medium was added daily. Alternatively, cells were cotransfected with 1.5 μg of either a control plasmid or the MEKA or PI3-K dominant-negative (p85ΔiSH2-N) mutant. Assays using NGF (100 ng/ml) were performed in a similar manner, with the exception that cells were transfected with 0.5 or 1.0 μg of the R-Ras3 dominant-negative mutant plasmid (pCEFL KZ AU5 R-Ras3 N27) and were subsequently incubated for 4 to 5 days after transfection in low-serum medium (1.5% serum) supplemented with NGF prior to scoring. For assays using GRP, cells were treated with 100 nM PMA 48 h after transfection and scored for processes. Alternatively, luciferase-based assays were performed 24 h after PMA treatment.

MAPK kinase assay.

For transient assays, 106 NIH 3T3 cells were transfected by a standard calcium phosphate precipitation method using 5 μg of either R-Ras3 L71, H-Ras R12, or a control plasmid. One day after transfection, cells were placed in 0.1% CS for 20 h and then solubilized in 600 μl of 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5)-2.5 mM MgCl2-10 mM EGTA (pH 8.0)-1% NP-40-40 mM β-glycerophosphate-2 mM Na3VO4-2 mM leupeptin-2 mM aprotinin-1 mM PMSF. Around 100 μg of cell lysate was boiled in Laemmli buffer and subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), followed by Western blot analysis with an anti-phospho p44/p42 ERK1 and ERK2 antibody. Blots were stripped and reprobed with an anti-ERK2 antibody to ensure that equal amounts of ERK were expressed. Similar MAPK assays were performed in PC12 cells, with the exception that cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 and were starved in medium containing 0.1% horse serum and 0.05% FCS.

B-Raf coimmunoprecipitation.

Using Lipofectamine 2000, approximately 5 × 106 PC12 cells were transfected with 5 μg of either pCEFL KZ AU5 R-Ras3 L71, H-Ras R12, or a control vector. Approximately 24 h after transfection, cells were placed in low-serum medium (0.1% horse serum and 0.05% FCS) for 20 h and cultures were solubilized in a buffer containing 1% NP-40, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 2 mM leupeptin, 2 mM aprotinin, and 1 mM PMSF. Approximately 1 μg of an anti-AU5 antibody was added to 1 mg of total cell extract and allowed to mix for 2 h at 4°C. Immunocomplexes were affinity absorbed onto 30 μl of γ-bind G Sepharose beads (Pharmacia) for an additional hour at 4°C. Beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and boiled in Laemmli buffer. Western blot analysis was performed using an anti-B-Raf antibody as well as the anti-AU5 antibody to detect the transfected R-Ras3 and H-Ras proteins. To demonstrate NGF-induced association of B-Raf and R-Ras3, PC12 cells were transfected as described above with 7.0 μg of pCEFL KZ AU5 R-Ras3 WT. Two days after transfection, cells were either left untreated or treated with NGF (100 ng/ml) for 5 min and solubilized in 600 μl of a hypotonic buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 5 mM Na4P2O7, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Na3VO4). Crude lysates were treated with 40 strokes in a Dounce homogenizer, and nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatants were then subjected to membrane fractionation by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 50 min at 4°C. The pellet which represented the membrane fraction was resuspended in a 1% NP-40 buffer as described above. Approximately 2 mg of membrane and cytoplasmic fractions was used for immunoprecipitation with an anti-AU5 antibody as described previously.

Raf kinase assays.

The Raf kinase assays were performed using a Raf-1 immunoprecipitation kinase cascade assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology). Briefly, PC12 cells were transfected with 5 μg of R-Ras3 L71, H-Ras R12, or a control vector. Around 24 h after transfection, cultures were placed in low-serum medium for 20 h as described previously. Cells were solubilized in a buffer composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM Na3VO4, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 1% Triton X-100, 50 mM NaF, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 10 mM sodium glycerophosphate, 0.1 mM PMSF, 2 mM leupeptin, and 2 mM aprotinin. Approximately 500 μg of total cell lysate was added to 2 μg of either anti-Raf-1 or anti-B-Raf antibodies bound to 100 μl of γ-bind G Sepharose beads (Pharmacia) and allowed to turn at 4°C for 2 h. Beads were washed twice with the lysis buffer, followed by one wash with an assay dilution buffer (20 mM MOPS [pH 7.2], 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM dithiothreitol). Kinase reactions were initiated by adding the following mixture to the beads: 20 μl of the assay dilution buffer, 10 μl of 500 μM ATP, 75 mM MgCl2 solution, 0.4 μg of MEK1, and 1 μg of ERK2. The resulting mixture was incubated at 30°C for 30 min. A 15-μl aliquot of the reaction was then boiled in Laemmli buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blot analysis with the anti-phospho p44/p42 ERK1 and ERK2 antibody.

RESULTS

Expression of R-Ras3 in juvenile mouse brains.

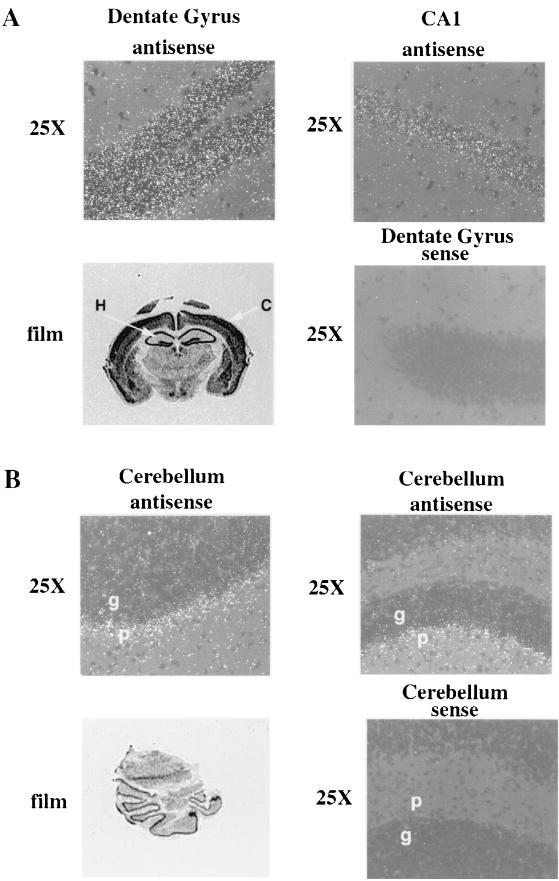

Due to the restricted nature of R-Ras3 expression, attempts to localize its transcripts to particular regions of the CNS were undertaken by in situ hybridization. Coronal sections of juvenile mouse brains were hybridized with a 393-bp radiolabeled R-Ras3 cRNA probe. As shown in Fig. 1, R-Ras3 transcripts were abundant in several areas of the brain, including the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum, as evidenced by the bright grains observed under dark-field microscopy or in sections exposed to X-ray film as autoradiography. Of particular interest was the high level of transcription seen in the entire hippocampal region (Fig. 1A, lower left panel). Moreover, R-Ras3 expression was confined only to the Purkinje cell layer of the cerebellum and was barely detectable in the granular cell layer (Fig. 1B, upper panels). H-Ras, in contrast, has been reported to be expressed in both of these layers of the cerebellum (43). The prominence and regional specificity of R-Ras3 transcripts in the CNS lend further credence to the hypothesis that this Ras-related G protein plays a critical role in certain neurally derived cells.

FIG. 1.

In situ hybridization of juvenile mouse brain tissue with an R-Ras3 cRNA probe. (Panels A) Two regions of the hippocampus (Dentate Gyrus and CA1) are depicted, illustrating the high levels of R-Ras3 expression evidenced by the bright grains under dark-field microscopy. An autoradiograph of an anterior coronal section exposed to X-ray film is shown (film) to demonstrate the high levels of R-Ras3 transcript seen in the cortex (C) as well as in the entire hippocampus (H). (Panels B) Sections of the cerebellum, showing the expression of R-Ras3 restricted mostly to the Purkinje (p) but not the granular (g) layer. A section exposed to X-ray film (film) shows this restricted expression pattern throughout the entire cerebellum. To ensure the specificity of the probe, sections were also hybridized with a sense R-Ras3 probe (sense), with no signal being detected.

Stimulation of R-Ras3 GTP binding by GRP and NGF.

In the mammalian CNS, the ability of the exchange factor GRF to stimulate the GTP binding of prototypic Ras has been well documented (13). In contrast, less is known about the role of two novel members of the Ras-signaling cascade, R-Ras3 and the exchange factor GRP. Interestingly, Stone and coworkers have shown that GRP is highly expressed in the mammalian hippocampus in a fashion similar to that of R-Ras3 (10). Based on these observations, we decided to test whether R-Ras3 could be regulated by GRP.

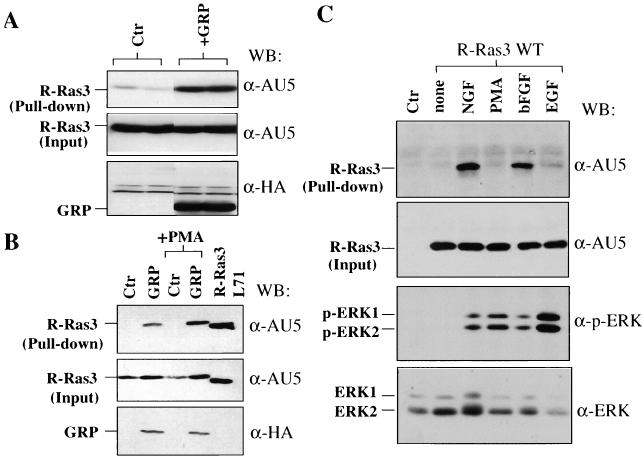

Due to the lack of an effective antibody for R-Ras3 for use in conventional GTP-loading experiments, we sought to develop an affinity pull-down assay, as described previously for the prototypic H-Ras (9). We have previously shown that R-Ras3 binds to the p110 catalytic subunit of PI3-K in a GTP-dependent manner (20). Thus, we utilized this interaction to determine the levels of GTP-bound R-Ras3 in vivo. For this purpose, the RBD of PI3-K (aa 127 to 314) was fused to GST (GST-p110 RBD) and purified from bacteria for use as a pull-down probe. Specificity of this probe was ascertained by comparing the relative abilities of the GST-p110 RBD and the WT R-Ras3 (R-Ras3 WT) to affinity precipitate the R-Ras3 L71-activated mutant. While no observable level of R-Ras3 WT was affinity precipitated in starved cultures, the activated mutant was readily detectable in the pull-down complex (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Stimulation of R-Ras3 GTP binding in mammalian cells. (A) 293T cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of AU5-tagged R-Ras3 WT along with 10 μg of either a control vector (Ctr) or an HA-tagged GRP exchange factor plasmid (+GRP). Transfected cells were starved in 0.3% FCS for 20 h and subsequently solubilized and incubated with the GST-p110 RBD pull-down probe. The affinity complexes were resolved on an SDS-12.5% polyacrylamide gel and subjected to Western blot analysis. Results from a representative of three experiments performed in duplicate are depicted. The amount of R-Ras3-GTP bound (pull-down) and its expression levels in total cell extracts (input) were detected using an anti-AU5 antibody. The expression levels of GRP were determined with an anti-HA antibody (lower panel). (B) The levels of the GTP-bound form of R-Ras3 were determined in PC12 cells by the affinity pull-down assay. Cultures were transfected with the AU5-tagged R-Ras3 WT plasmid together with the indicated plasmids. Transfected cells were maintained in low-serum conditions (1.0% serum) for 20 h, and selected cultures were treated with 100 nM PMA. As a positive control, an activated mutant of R-Ras3 (R-Ras3 L71) was included. A representative of at least two experiments is shown, and Western blot analysis was carried out as described for panel A. (C) The relative ability of different factors to stimulate transfected R-Ras3 in PC12 cells was assayed as for panel B. The efficacy of the stimuli was monitored based on their ability to activate ERK phosphorylation (p-ERK1 and p-ERK2).

Using this assay, we attempted to determine whether R-Ras3 could be activated by GRP in cultured cells. For this purpose, GRP was coexpressed with R-Ras3 WT in 293T cells. Transfected cultures were deprived of serum for 20 h, and total cell extracts were prepared for affinity pull-down with GST-p110 RBD. As shown in Fig. 2A, whereas cotransfection of a control plasmid with R-Ras3 WT produced a low basal level of GTP-bound R-Ras3 WT, the coexpression of GRP markedly stimulated the amount of GTP-bound R-Ras3 WT by approximately 15-fold, as determined by densitometric analysis. The total level of R-Ras3 WT protein in each transfected culture remained, however, at a very similar level.

Activation of R-Ras3 GTP loading in PC12 cells.

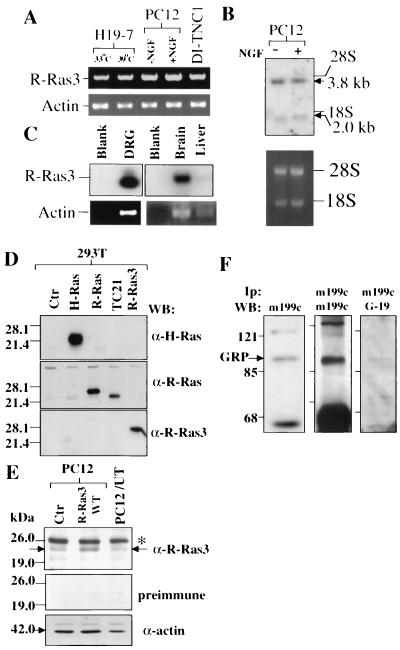

The high level of expression of both R-Ras3 and GRP in the mammalian nervous system prompted us to investigate the activation of R-Ras3 in a neuronal cell system. For this, the PC12 cell line was selected, since it is a well-characterized system that has been extensively used to study neuronal survival and differentiation. To ascertain the expression of both R-Ras3 and GRP in PC12 cells, levels of their RNA and protein were examined. By reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, ∼630 bp products were amplified from PC12 as well as from hippocampal neurons (H19-7) and astrocytes (DI-TNC1) (Fig. 3A). Next, Northern blot analysis using a rat R-Ras3 cDNA probe revealed transcripts of 3.8 and 2.0 kb in PC12, which corresponds to the size of R-Ras3 mRNA in both humans and mice (Fig. 3B) (18, 29). Since PC12 cells are most closely related to peripheral neurons, we also sought to determine whether R-Ras3 showed expression in this cell type. Total RNA was first extracted from primary cultures of mouse dorsal root ganglion (established from the embryonic day 12 stage) which had been exposed to the antimitotic agent cytosine β-d-arabinofuranoside (ara-C) for 6 days to eliminate proliferating glial cells. Next, using a similar RT-PCR strategy, a ∼630-bp band was detected, which in turn hybridized with a [α32P]dCTP-labeled mouse R-Ras3 probe (Fig. 3C). A similarly sized band representing R-Ras3 was readily detectable in an RNA sample prepared from the mouse brain but was expressed at a much lower level in the liver.

FIG. 3.

Expression of R-Ras3 and GRP in PC12 cells. (A) RT-PCR was performed using cDNA prepared from H19-7 cells exposed to different temperatures, from PC12 cells, and from DI-TNC1 cells. All PCRs were resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The ∼630-bp products amplified using R-Ras3 specific primers are indicated. As the control, parallel tubes were amplified using a pair of actin primers (lower panel). (B) Northern blot analysis of R-Ras3 expression was carried out using total RNA prepared from PC12 cells treated with NGF (+) or left untreated (−). RNA was transferred onto nitrocellulose filters and hybridized with a [α32P]dCTP-labeled rat R-Ras3 cDNA probe. The two R-Ras3 transcripts are indicated, and equal sample loading was ascertained by the levels of ethidium bromide-stained 28S and 18S rRNA (lower panel). (C) The expression of R-Ras3 in various tissues was analyzed by RT-PCR techniques as described for panel A, except that the authenticity of the PCR-amplified products was confirmed by Southern blot analysis with a [α32P]dCTP-labeled mouse R-Ras3 cDNA probe. DRG, dorsal root ganglion. (D) An anti-R-Ras3 polyclonal antibody was tested for specificity using 293T cell lysates overexpressing various Ras-related GTPases. Individual filters were incubated with the indicated antibodies (upper three panels). (E) A similar Western blot analysis was performed using 60 μg of total cell extracts from PC12 cells transfected either with a control plasmid (Ctr) or a non-epitope-tagged WT R-Ras3 expression vector. An additional lane was also loaded with 30 μg of an untreated PC12 lysate (PC12/UT). The arrow indicates the mobility of R-Ras3. The identity of a higher-molecular-mass band was not known (asterisk). Parallel Western blots were also incubated with the preimmune serum or an anti-actin antibody to confirm equal protein loading. (F) Expression of GRP in PC12 cellswas examined. PC12 lysate was subjected to Western blot analysis with the anti-GRP monoclonal antibody m199c (left panel). Alternatively, GRP was first immunoprecipitated (Ip) from ∼1 mg of PC12 lysate with m199c followed by Western blot (WB) analysis using m199c (middle panel) or an anti-GRP goat polyclonal antibody, G-19 (right panel). The predicted ∼90-kDa gene product of GRP is indicated with an arrow.

Finally, to analyze R-Ras3 protein expression, we first tested the specificity of an anti-R-Ras3 polyclonal antibody, R3G. As shown in Fig. 3D, R3G did not display significant cross-reactivity with three closely related GTPases, H-Ras, R-Ras, and TC21, which were overexpressed by more than 10-fold in 293T cells. Next, Western blot analysis was performed using cell lysates derived from PC12 cells. For a positive control, we transfected the PC12 cells using an expression vector which contained an untagged WT R-Ras3 to achieve a ∼threefold overexpression of the protein. R3G in this case detected a protein species in the control culture which exhibited a level of mobility that was identical to that of the overexpressed WT R-Ras3 protein (Fig. 3E). These protein species were not detected when the preimmune serum was used.

To demonstrate the expression of GRP in PC12 cells, Western blot analysis was first performed with a monoclonal antibody, m199c, which was generated against the full-length GRP. As shown in Fig. 3F, a 90-kDa species was detected, which was consistent with the predicted molecular mass of full-length GRP (10). To ascertain the authenticity of this protein species, immunoprecipitation was carried out using the m199c antibody, followed by immunoblotting with either the same antibody or a polyclonal antibody, G-19, which was directed against the C terminus of GRP. As expected, a similar ∼90-kDa band was detected in the PC12 lysate in both cases.

Next, changes in the GTP-bound state of R-Ras3 were investigated when PC12 cells were either transfected with GRP or exposed to different trophic factors. As shown in Fig. 2B, when coexpressed with R-Ras3 in PC12 cells, GRP stimulated R-Ras3 GTP binding by at least 14-fold. It has been previously shown that GRP has a diacylglycerol (DAG)-binding domain and that its exchange activity is augmented upon the addition of a DAG analog, PMA (10). As expected, when transfected PC12 cells were triggered with PMA, the ability of GRP to activate R-Ras3 was further enhanced, by ∼threefold (Fig. 2B).

Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of members of the Ras gene family in controlling cell growth and differentiation in response to trophic factors in PC12 cells (42, 44). To investigate whether R-Ras3 showed differential responses to different exogenous stimuli, the activation state of R-Ras3 was examined in PC12 cells treated with NGF, PMA bFGF, and EGF. As shown in Fig. 2C, exposure of PC12 to NGF and bFGF led to the rapid activation (within 5 min) of ectopically expressed R-Ras3 while both EGF and PMA failed to elicit any detectable response under the same experimental conditions. In addition, the effectiveness of these external stimuli was confirmed by their ability to stimulate the MAPK cascade, as indicated by the rapid phosphorylation of the ERK1 and ERK2 (Fig. 2C). Based on all these experiments, we conclude that R-Ras3 is subjected to regulation by selective upstream activators in PC12 cells.

R-Ras3 and GRP promote neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells.

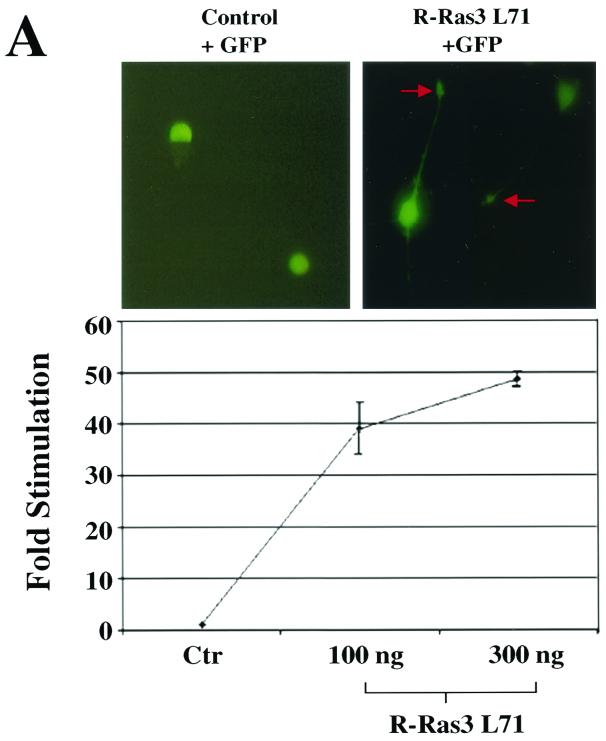

The ability of NGF to activate R-Ras3 and its propensity to promote neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells led us to test whether R-Ras3 could also induce neuronal differentiation in this cell system. For this, we transfected PC12 cells with the R-Ras3 L71 expression vector together with a plasmid encoding the green fluorescent protein (GFP) in a limiting amount as a marker for transfected cells. As illustrated in Fig. 4A, expression of R-Ras3 L71 in PC12 cells caused a striking protrusion of neurite-like processes. This phenomenon was highly efficient, as over 70% of the GFP-positive cells displayed processes greater than two times the cell diameter. Furthermore, transfection of PC12 with a R-Ras3 L71 cDNA in the pBabe-puro expression construct followed by puromycin selection resulted in neurite outgrowth in nearly all selected cells (data not shown). These data indicated that R-Ras3-induced morphological differentiation was a direct effect in transfected PC12 cells, but we do not exclude the possibility that the observed phenomenon was due to the production of paracrine factors.

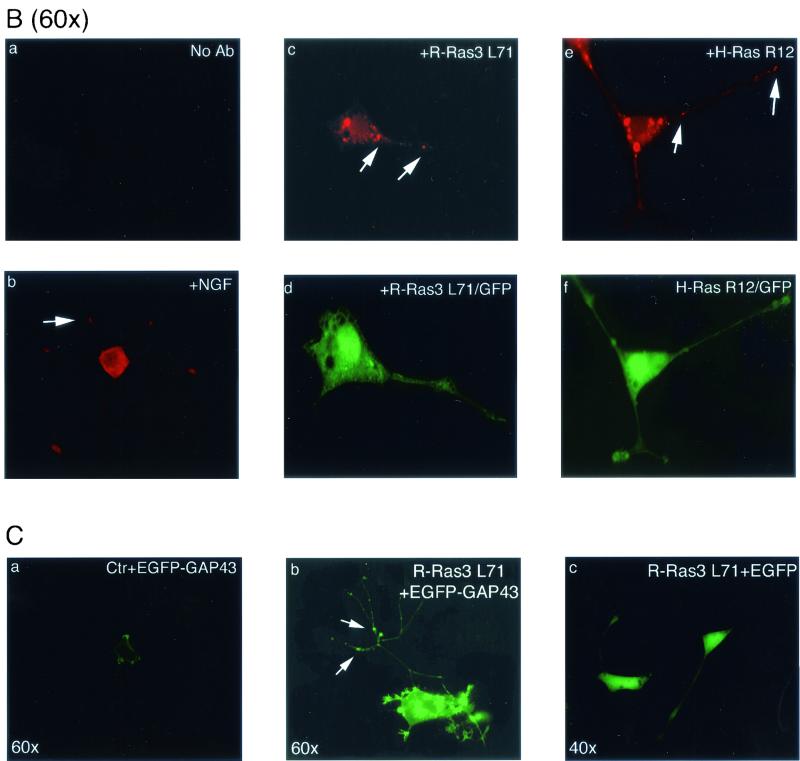

FIG. 4.

R-Ras3-induced differentiation in PC12. (A) PC12 cells were transfected with 2 μg of either a control vector (top left panel) or an activated R-Ras3 (R-Ras3 L71) expression plasmid (top right panel) (×40 magnification). To mark transfected cells, a GFP expression plasmid was cotransfected in each case. Two representative R-Ras3-transfected cells are shown 48 h after transfection, demonstrating the protrusion of neurites and growth cone-like structures as indicated with red arrows (top right panel). R-Ras3-induced neuronal differentiation was also measured by the NF-L transcriptional reporter assay, as described in the Materials and Methods section (lower panel). PC12 cells were transfected with an increasing amount of R-Ras3 L71 along with 1 μg of the reporter plasmid, and the luciferase activity was measured 48 h later. All luciferase readings were normalized to the amount of total cell lysate and expressed as fold increase over control vector (Ctr)-transfected cells. Error bars represent standard deviations derived from triplicate plates of a representative experiment performed at least twice. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of GAP-43 expression in differentiated PC12 cells. PC12 cells were transfected with a control vector (panels a and b) or cotransfected with R-Ras3 L71 and GFP (panels c and d) or H-Ras R12 and GFP (panels e and f). Vector-transfected cells were left untreated (panel a) or treated with (panel b) NGF for 3 days. Expression and localization of GAP-43 were investigated with an anti-GAP-43 antibody and then detected with a Texas Red-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (panels b, c, and e). One of the vector-transfected control cultures was not incubated with the primary antibody and served as a negative control (panel a). Vesicular expression of GAP-43 along the neurites is indicated with arrows. Transfected cells were determined by GFP fluorescence signals (panels d and f). (C) To confirm the GAP-43 expression data, PC12 cells were transfected with a pCA-GAP-EGFP expression plasmid together with either a control vector (panel a) or R-Ras3 L71 (panel b). Arrows highlight the accumulation of punctate green fluorescence signals along the neurites. In contrast, R-Ras3 L71 cotransfected with the pCA-EGFP control plasmid displayed a more homogenous staining pattern throughout the entire cell (panel c shows two such cells [×40 magnification]).

As an additional readout of neuronal differentiation, we measured the transcriptional activity of the NF-L gene, which encodes a class of intermediate filaments that are specifically expressed in the mammalian neurons. In fact, differentiation of PC12 cells by NGF has been shown to correlate with an increase in NF-L gene transcription (38). For this measurement, transcriptional reporter gene assays were performed using a plasmid containing the promoter of NF-L gene placed upstream of the luciferase reporter. When transfected with a control vector, no significant luciferase activity was detected (Fig. 4A). However, introduction of the R-Ras3 L71 plasmid stimulated a robust transactivation of the reporter gene by 40- to 50-fold.

To investigate whether neuronal differentiation induced by NGF and R-Ras3 L71 displayed qualitative differences, we monitored the expression and localization of growth-associated protein-43 (GAP-43). GAP-43 is a membrane protein that has been implicated in the neuronal outgrowth and synaptic plasticity of developing and regenerating neurons (31). As had been observed previously, PC12 cells treated with NGF for 4 days displayed four to five well-defined neurites, and GAP-43 staining was detected in the cell body and the terminal growth cones (Fig. 4B, panel b). In contrast, PC12 cells transfected with R-Ras3 L71 produced one to two neurites with occasional protrusions along the length of the processes (Fig. 4B, panels c and d). When immunofluorescence analysis was performed 36 h after transfection, GAP-43 was detected, mostly in the vesicular compartments along the neuritic processes. Similarly, H-Ras induced neuronal differentiation which very much resembled that of R-Ras3 L71 (Fig. 4B, panels e and f). To further substantiate these findings, we coexpressed R-Ras3 L71 and a fusion protein which comprised an enhanced GFP (EGFP) and the amino-terminal 20-aa membrane-targeting domain of GAP-43 (EGFP-GAP43) (33). As shown in panel a of Fig. 4C, EGFP-GAP43 was mainly localized to the membrane of control vector-transfected cells. However, in R-Ras3 L71-expressing PC12 cells, EGFP-GAP43 was detected as punctate signals resembling trafficking vesicles along the neurites, and strong staining was also observed in the cell body (Fig. 4C, panel b). In contrast, cells cotransfected with R-Ras3 L71 and the control vector EGFP displayed a more even distribution of green fluorescence signals throughout the entire cell (Fig. 4C, panel c). Thus, R-Ras3-induced neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells showed quantitative and qualitative differences from that of NGF.

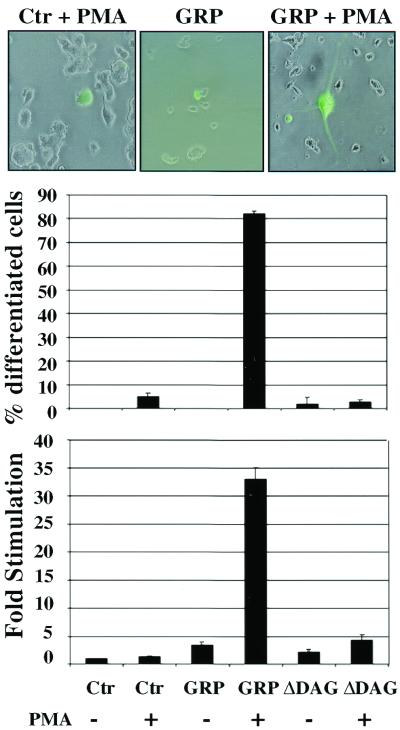

Next, we investigated whether GRP could also promote differentiation of PC12 cells. Interestingly, expression of GRP alone failed to evoke morphological differentiation, even after a prolonged period of incubation (Fig. 5, center micrograph and middle panel). However, exposure of these transfectants to PMA resulted in the appearance of neurite outgrowth in over 80% of the transfected cells (Fig. 5, right micrograph), while the presence of PMA alone failed to elicit a similar response (left micrograph). This result was in accordance with the previous finding that PMA addition allowed GRP to further promote R-Ras3 activation. Although GRP alone could activate R-Ras3 GTP binding, it is possible that a maximal activation of R-Ras3 is required for efficient neuronal differentiation. Furthermore, to ensure that this differentiation event was due to an increase in GTP exchange on R-Ras3 stimulated by PMA, a mutant form of GRP lacking the DAG-binding domain (GRP-ΔDAG) was used as a negative control. This mutant has been shown previously to be nonresponsive to PMA stimulation (10). As expected, GRP-ΔDAG was unable to induce differentiation in either the presence or absence of PMA (Fig. 5, middle panel). These biological data were further validated by the NF-L transcriptional reporter assays, with which nearly identical results were obtained (Fig. 5, lower panel). Thus, the ability of GRP to promote efficient neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells may require its targeting to the plasma membrane by DAG.

FIG. 5.

GRP-induced differentiation of PC12 cells. Morphological differentiation of PC12 cells was induced by ectopic expression of GRP only in the presence of 100 nM PMA. Control (Ctr) cells exposed to PMA (left micrograph) or GRP alone (center micrograph) failed to induce neurite outgrowth in GFP-marked cells. The extent of GRP-induced differentiation in the presence of PMA was quantified by scoring ∼50 GFP-positive cells for neurites (middle panel). Error bars represent standard deviations derived from a representative experiment performed at least twice. GRP effects on PC12 cells were further ascertained using the NF-L luciferase reporter as described for Fig. 4 (bottom panel). Cells were transfected with 2 μg of either GRP or GRPΔDAG (which does not bind the DAG analogue PMA). Luciferase activity was measured in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 100 nM PMA. The data are expressed as fold increase over control, with error bars representing standard deviations derived from triplicate measurements of a representative experiment.

GRP- and NGF-induced neurite outgrowth is blocked by an R-Ras3 dominant negative.

Since both GRP and NGF could stimulate neurite outgrowth and activate R-Ras3, it is possible that R-Ras3 may be a critical downstream signaling molecule for neuronal differentiation. To test this possibility, we examined the ability of a dominant-negative mutant of R-Ras3 (R-Ras3 N27) to block neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells. To examine the requirement of R-Ras3 for GRP-induced differentiation, we performed NF-L transcriptional reporter assays by cotransfecting GRP with either a control vector or R-Ras3 N27 in PC12 cells in the presence of PMA. As shown in Fig. 6A, R-Ras3 N27 hampered the ability of GRP to transactivate the NF-L promoter by more than 50% compared to that of the control. Next, we tested whether NGF-induced differentiation in PC12 cells was also attenuated by the R-Ras3 dominant-negative mutant. For this test, we quantified the extent of neurite outgrowth using the morphological assays as described above. Cells were first cotransfected with R-Ras3 N27 and a GFP plasmid as a marker for transfection, and the fraction of green cells possessing neurites was scored four days after NGF addition. As shown in Fig. 6B, the R-Ras3 N27 inhibited NGF-induced neurite outgrowth by ∼75% compared to the control vector.

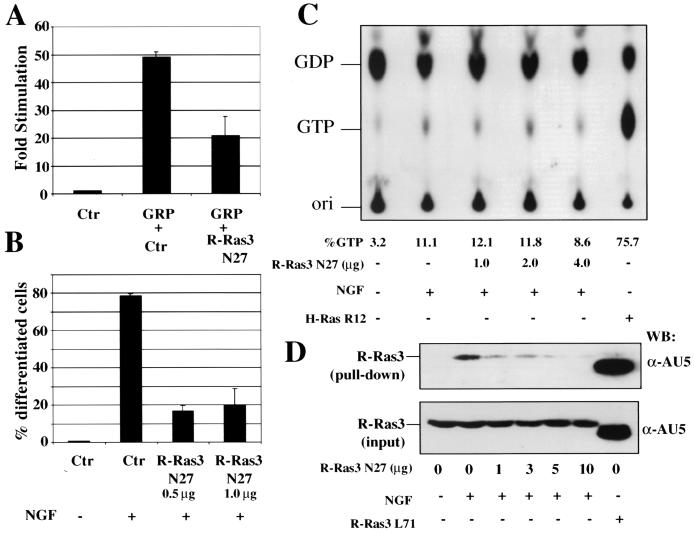

FIG. 6.

The role of R-Ras3 in PC12 differentiation. (A) PC12 cells were transfected with GRP (2 μg), a control vector (0.5 μg), and R-Ras3 N27 dominant-negative mutant (0.5 μg). Around 48 h after transfection, 100 nM PMA was added, and luciferase reporter assays were performed 24 h later. The data are expressed as fold increase over control, with error bars representing standard deviations derived from a representative experiment of two performed. (B) PC12 cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of R-Ras3 N27 or with a control vector (Ctr). To mark transfected cells, 0.2 μg of a GFP expression plasmid was cotransfected in each plate. Cultures were treated with NGF (100 ng/ml) 24 h after transfection. The number of cells with neurites was scored by assessing at least 50 transfected cells 3 days later. The results of a representative experiment performed at least twice are shown with error bars representing the standard deviations derived from triplicate measurements. (C) The ability of R-Ras3 N27 to block H-Ras activation was examined by first transfecting PC12 cells with the indicated amount of R-Ras3 N27. As a positive control, parallel cultures were transfected with an oncogenic H-Ras R12 expression plasmid. Cells were then metabolically labeled with [α32P]orthophosphate for 5 h, and selected cultures were exposed to NGF for 5 min. H-Ras proteins were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Ras antibody, and the nucleotide bound was resolved on a thin-layer chromatography plate. The percentage of GTP was determined, and results are from a single experiment which had been repeated once with similar results being obtained. (D) The efficacy of R-Ras3 N27 in blocking activation of R-Ras3 WT by NGF was investigated. PC12 cells were transfected with the indicated amount of R-Ras3 N27 followed by the addition of NGF for 5 min. The level of R-Ras3-GTP was monitored by assessing binding to the GST-p110 RBD fusion protein as described in the legend of Fig. 2. A greater than 70% inhibition of R-Ras3 activation was observed with the use of only 1 μg of R-Ras3 N27.

Because it has been shown that R-Ras3 and Ras may share some of the upstream exchange factors, we tested whether the R-Ras3 dominant-negative mutant could block Ras activation. For this, the Ras-GTP level was measured in NGF-induced PC12 cells in the presence of an increasing amount of R-Ras3 N27. As shown in Fig. 6C, the level of Ras-GTP increased from ∼3% to ∼11% upon NGF addition, a magnitude commonly reported by others (44). Coexpression of an increasing amount of R-Ras3 N27 failed to significantly suppress the level of Ras-GTP upon NGF triggering. This observation was particularly significant, since transfecting a low level of R-Ras3 N27 was sufficient to induce a >80% suppression of NGF biological action. Furthermore, this level of R-Ras3 N27, which has a negligible effect on Ras-GTP loading, efficiently blocked R-Ras3 activation by ∼80% (Fig. 6D). Thus, the inhibitory effects of R-Ras3 N27 were unlikely to be the result of a block in the activation of endogenous Ras. However, although other small G proteins such as Rap1A and Ral have not been shown to share overlapping exchange factors with R-Ras3 (32), we do not exclude the possibility that R-Ras3 N27 may inhibit the activation of other GTPases yet unknown.

R-Ras3 promotes PC12 differentiation through the MAPK pathway.

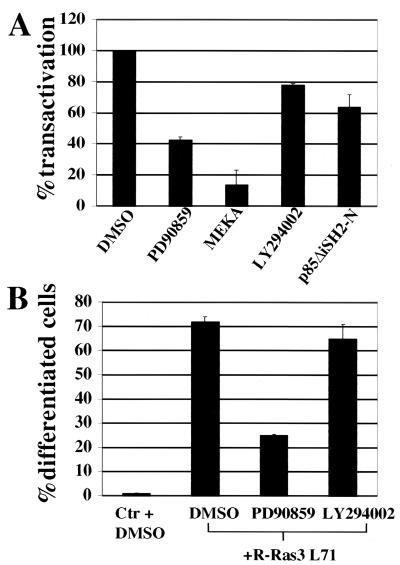

We have previously reported that R-Ras3 can promote survival in PC12 cells in a PI3-K-dependent manner (20). Furthermore, our group has also shown that R-Ras3 does not activate the MAPK pathway in mouse fibroblast cells (20). Based on these observations, it is very likely that R-Ras3-induced differentiation is also dependent on PI3-K. To test this hypothesis, NF-L reporter assays were performed to test whether either a dominant-negative mutant of the PI3-K (p85ΔiSH2-N) or a specific pharmacological inhibitor, LY294002, could block R-Ras3 L71-induced transactivation. In parallel, we also examined the involvement of the MAPK pathway by introducing MEKA and PD90859, a chemical inhibitor of MEK. All of the dominant-negative mutants and inhibitors have been previously shown to be specific and were used at noncytotoxic concentrations (21, 34, 40). Interestingly, inhibiting PI3-K only moderately blocked the R-Ras3-induced differentiation response. In contrast, attenuating the MAPK pathway with MEKA or PD90859 markedly inhibited the ability of R-Ras3 to transactivate the reporter gene by ∼85% or ∼60%, respectively (Fig. 7A). To ascertain whether these specific inhibitors displayed similar effects on morphological differentiation, the extent of neurite outgrowth was quantified as described above. As expected, the ability of LY294002 and PD90859 to inhibit R-Ras3-induced neuronal differentiation was essentially identical to that shown by the results of the NF-L report assay (Fig. 7 B).

FIG. 7.

Effects of MAPK- and PI3-K-specific inhibitors on R-Ras3-induced neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells. (A) The ability of R-Ras3 L71 to promote transactivation from the NF-L luciferase reporter was determined in the presence of either a chemical inhibitor or a dominant-negative mutant of the MAPK (50 μM PD90859 [MEKA]) or PI3-K (10 μM LY294002 [p85ΔiSH2-N]) pathway. The data delineate the percentage of suppression of transactivation by these inhibitors. Error bars represent standard deviations derived from a representative of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. (B) Parallel cultures cotransfected with R-Ras3 L71 and GFP were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide, PD90859, or LY294002. The fraction of GFP-positive cells which displayed morphological differentiation was scored as outlined for Fig. 4. Data represent results from triplicate measurements, with standard deviations derived from a representative of two independent experiments.

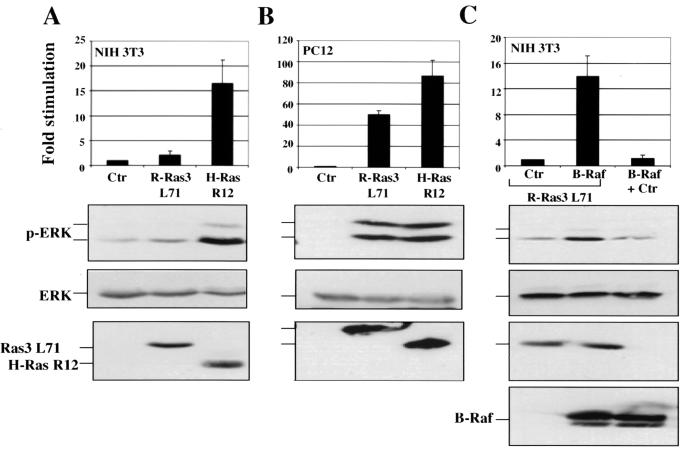

R-Ras3 activates MAPK in a cell-type-specific manner.

These unexpected findings led us to investigate the idea that R-Ras3 showed a disparate propensity to activate MAPK in NIH 3T3 versus PC12 cells. To test this hypothesis, MAPK assays were performed by transiently transfecting R-Ras3 L71 and H-Ras R12 expression plasmids in both cell lines. The activation state of MAPK was monitored by a phospho-specific antibody that recognizes the phosphorylated and thus activated forms of MAPK. As shown in Fig. 8A and B, while R-Ras3 only marginally activated MAPK in NIH 3T3 cells, it stimulated a 50-fold activation in PC12 cells when compared with the vector control. On the other hand, H-Ras R12 exhibited the expected robust activation of MAPK in both NIH 3T3 and PC12 cells.

FIG. 8.

Activation of MAPK pathway by R-Ras3. (A) NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with 5 μg of expression plasmids for activated R-Ras3 (R-Ras L71), H-Ras (H-Ras R12), or a control plasmid (Ctr). Approximately 100 μg of total cell lysate was resolved on an SDS-12.5% polyacrylamide gel, followed by Western blot analysis with a phospho-specific ERK antibody (p-ERK). The levels of ERK were determined using an anti-ERK2 antibody (ERK). The levels of R-Ras3 L71 and H-Ras R12 were detected using an anti-AU5 antibody. (B) The ability of R-Ras3 L71 and H-Ras R12 to activate the MAPK pathway was analyzed in PC12 cells under conditions similar to that described for NIH 3T3 cells. (C) To restore the ability of R-Ras3 to activate ERK in NIH 3T3 cells, 10 μg of either control vector (Ctr) or B-Raf plasmid was cotransfected along with 5 μg of R-Ras3 L71 expression plasmid in NIH 3T3 cells. B-Raf alone failed to stimulate any detectable activation of ERK. All results were quantified and were derived from a representative experiment that was performed at least twice and are expressed as fold increase compared to the control, with error bars representing standard deviations derived from triplicate plates.

The inability of R-Ras3 to activate MAPK in NIH 3T3 cells can be explained by our previous finding that R-Ras3 has only a modest affinity for c-Raf (19). In addition, it is likely that an essential protein is absent in NIH 3T3 cells which is normally present in PC12 cells. An obvious candidate for such a protein would be B-Raf, whose expression, like that of R-Ras3, is highly restricted to the CNS. In fact, NIH 3T3 cells predominantly express c-Raf, but not B-Raf, while PC12 cells express high levels of both Raf isoforms (42). To test the hypothesis that B-Raf is the protein that is absent in NIH 3T3 cells, we sought to recapitulate the conditions found in PC12 cells by ectopically expressing B-Raf in NIH 3T3 cells. As shown in Fig. 8C, cells coexpressing both R-Ras3 and B-Raf displayed a synergistic effect in their activation of MAPK by 14-fold, a level very similar to that elicited by H-Ras R12 alone. In contrast, B-Raf expression alone did not produce any significant activation when experiments were performed under similar conditions.

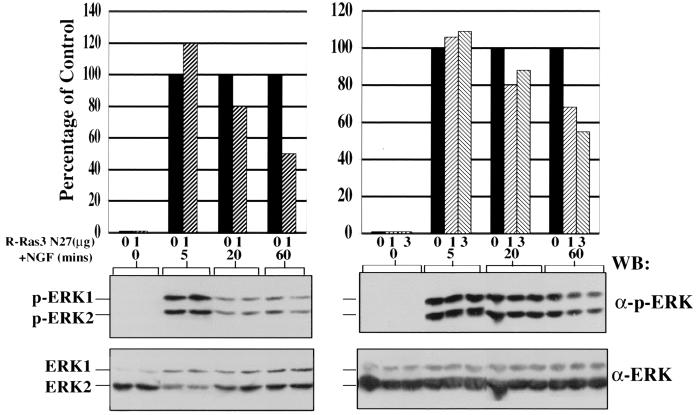

Previous studies have implicated members of the Ras subfamily in mediating MAPK activation upon NGF treatment in PC12 cells. To investigate whether R-Ras3 was a component of this signaling network, we examined whether R-Ras3 N27 could block NGF-induced MAPK activation. As shown in Fig. 9, the robust activation of MAPK was not significantly dampened by the presence of R-Ras3 N27 within 5 min of NGF addition. A ∼20% block was observed after 20 min of treatment with this trophic factor. However, there was a reproducible 50% reduction of ERK phosphorylation at the later time point of 60 min. Given the fact that the transfection efficiency of these experiments was ∼80%, the actual level of inhibition could have been higher than that of the suppression observed. We conclude from these experiments that R-Ras3 appears to display cell type specificity in activating the MAPK signaling cascade and that this activation may be required for neuronal differentiation.

FIG. 9.

Effects of expressing R-Ras3 N27 on NGF-induced MAPK activity. PC12 cells were transfected with the indicated amount of R-Ras3 N27 or control (Ctr) vector. Cells were treated with NGF, and the extent of phosphorylation of ERK1 and ERK2 was monitored at various time points. Results from two separate experiments are shown. The band intensity of phosphorylated ERK1 and ERK2 was first quantified by an imaging densitometer and then normalized for the corresponding expression levels of total ERK1 and ERK2. Data are summarized in the top panel, which represents the percentages of ERK1 and ERK2 phosphorylation relative to the vector control-transfected cells at the indicated time point.

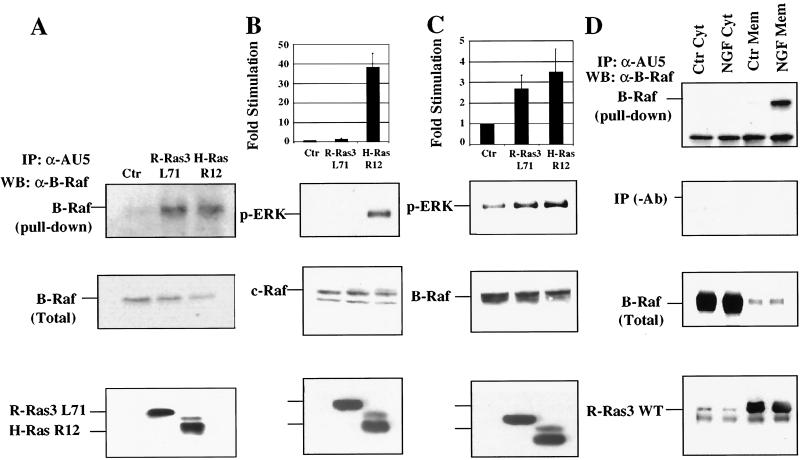

R-Ras3 interacts with and activates B-Raf in PC12 cells.

The cooperative effect observed between R-Ras3 and B-Raf led us to test whether they can form a complex in vivo. For this test, PC12 cells were first transfected with R-Ras3 L71, H-Ras R12, or a control plasmid. Cells were solubilized, and G proteins were immunoprecipitated using an anti-AU5 antibody. The presence of B-Raf in the immunocomplexes was then detected using Western blot analysis. As depicted in Fig. 10A, whereas immunocomplexes from control transfectants lacked any detectable endogenous B-Raf, those from R-Ras3- and H-Ras-transfected cells displayed a similar amount of coimmunoprecipitated B-Raf.

FIG. 10.

Binding and activation of B-Raf by R-Ras3. (A) PC12 cells were transfected with 5 μg of R-Ras3 L71, H-Ras R12, or a control (Ctr) plasmid. R-Ras3 and H-Ras were immunoprecipitated (IP) from total cell extracts by using an anti-AU5 antibody. The resultant immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis (WB). The top panel shows the amount of B-Raf present in the immunoprecipitates. The middle panel shows the levels of B-Raf expression in total cell lysate, and the lower panel shows the expression of transfected R-Ras3 L71 and H-Ras R12 using the anti-AU5 antibody. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) PC12 cells were transfected with 5 μg of the indicated plasmids. After incubation in low-serum medium, c-Raf was immunoprecipitated and in vitro Raf kinase assays were performed after adding recombinant MEK1 and ERK2. The reaction products were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blot analysis with the phospho-specific ERK antibody (p-ERK). The levels of c-Raf, R-Ras3 L71, and H-Ras R12 were determined with their respective antibodies. The results of two independent experiments were quantified by densitometric analysis and expressed as fold increase compared to control (top panel). (C) Similar kinase assays were performed for B-Raf, using essentially the same method as that described for panel B. (D) NGF-induced B-Raf recruitment to the plasma membrane by R-Ras3 was investigated. Approximately 3 × 106 PC12 cells were transfected with 6 μg of R-Ras3 WT expression vector and treated with NGF (+) or left untreated (−) for 5 min. Total cell extract were prepared and fractionated into cytosolic (Cyt) or membrane (Mem) fractions. R-Ras3 WT was immunoprecipitated with an anti-AU5 antibody, and the associated B-Raf was mainly found in the membrane fraction of NGF-stimulated cells (top panel). The expression of B-Raf and R-Ras3 was mainly confined to the cytosol and membrane fractions, respectively (bottom two panels).

To substantiate these findings, we sought to compare the abilities of R-Ras3 and H-Ras to activate the two Raf isoforms in PC12 cells. Of note, H-Ras has been shown to activate both Raf isoforms (27). For this comparison, PC12 cells were transiently transfected with R-Ras3 L71, H-Ras R12, or a control vector and endogenous B-Raf or c-Raf was immunoprecipitated using their respective antibodies. In vitro kinase assays were then performed by the addition of recombinant MEK1 and ERK2, and activation events were monitored by the phospho-specific ERK antibody. As illustrated in Fig. 10B, whereas H-Ras R12 produced a ∼38-fold activation of c-Raf, R-Ras3 L71 failed to exhibit any detectable stimulation under similar experimental conditions. In contrast, R-Ras3 and H-Ras elicited comparable levels of B-Raf activation of 2.7 and 3.5-fold, respectively (Fig. 10C). The lower fold level of activation seen in the B-Raf kinase assays reflects the higher basal activity of the kinase, as previously reported (27).

Finally, to prove that R-Ras3 could serve as a signaling intermediate linking NGF and B-Raf activation, we sought to demonstrate the ability of R-Ras3 to recruit B-Raf to the cell membrane in an NGF-inducible manner. For this, PC12 cells were transfected with R-Ras3 WT and then stimulated with NGF for 5 min. Membrane and cytoplasmic fractions were prepared, and the amount of B-Raf associated with R-Ras3 WT immunocomplexes was then quantified. As shown in Fig. 10D, while B-Raf was absent in the membrane fraction of the unstimulated cells, it was clearly associated with R-Ras3 WT in the membrane of NGF-treated cells. Taken together, all these results reveal a potential novel signaling cascade involved in R-Ras3-induced neuronal differentiation through B-Raf and MAPK.

DISCUSSION

Unlike that of other members of the Ras subfamily, R-Ras3 expression is highly restricted to the mammalian nervous system. Therefore, this G protein is likely to serve as a critical signal transducer for neurotrophic factors essential for growth and differentiation. Indeed, we have demonstrated that R-Ras3 is activated by NGF as well as by a Ras exchange factor, GRP, which is enriched in the hippocampus. Biologically, R-Ras3 possesses dual functionality in PC12 cells. First, as previously reported, R-Ras3 can promote survival in differentiated PC12 cells deprived of NGF (20). In this study, we have demonstrated that R-Ras3 can cause the robust differentiation of PC12 cells and that a dominant-negative mutant of R-Ras3 can attenuate differentiation events caused by both NGF and GRP.

Our observation that R-Ras3 expression in the cerebellum is highly restricted to the Purkinje cell layer highlights a major departure from the characteristics of its close relative, H-Ras. The cerebellum has been shown to be responsible for the control of movements and postural adjustments. The Purkinje cells, in particular, reside in the cerebellar cortex and are characterized by a large dendritic tree. These neurons provide the sole connection from the cerebellar cortex to the deep cerebellar nuclei (17). Interestingly, unlike most other neurons in the brain, which receive an average of about 1,000 synapses, the Purkinje cells can have up to 200,000 (17). Whether R-Ras3 plays a role in the signal transduction of these synapses remains to be seen, and a more detailed analysis of its function in primary neuronal cultures is required.

Several GEFs, including GRP, have been shown to have an elevated expression in the CNS; however, little is known about the physiological role of GRP in neurally derived cells. At the biochemical level, GRP is presumably activated by the second messenger, DAG, through binding to a DAG-binding domain of the exchange factor (10). Our results have established a novel link between GRP and R-Ras3 in PC12 cells, as demonstrated by the following three observations: (i) GRP increases the levels of the GTP-bound form of R-Ras3, (ii) both GRP and R-Ras3 stimulate neurite outgrowth, and (iii) inhibition of R-Ras3 results in an attenuation of GRP-induced neuronal differentiation. It is at present unclear whether GRP can be activated directly by NGF. However, others have shown that DAG is upregulated in PC12 cells upon NGF stimulation (25). To address this question, we are presently constructing a dominant-negative GRP which lacks the exchange factor domain to test whether it can block NGF action.

We have shown that the expression of GRP alone in PC12, while able to activate R-Ras3, is nevertheless incapable of inducing differentiation unless PMA is added. This apparent inconsistency can be explained by the fact that a critical threshold level of R-Ras3-GTP is needed to evoke a full differentiation response. In addition, PMA may also activate other novel DAG-dependent GEFs that together with GRP contribute to neuronal differentiation in a synergistic manner. It is also intriguing that while PMA fails to stimulate R-Ras3, both NGF and bFGF are very effective in doing so. One plausible explanation is that the endogenous level of GRP may not be sufficiently high enough to efficiently activate R-Ras3. Alternatively, PMA, given that it is an analogue of DAG, is not expected to be as effective in promoting the translocation of the majority of the GRP to the cell membrane where R-Ras3 is localized.

While we have shown a potential role for R-Ras3 and GRP in neuronal differentiation, the situation is further complicated by the presence of a repertoire of GEFs with similar biochemical specificity. For example, two separate groups have recently shown that Sos and GRF stimulate exchange on R-Ras3 both in vitro and in vivo (32, 36). Consistent with our findings, Ohba et al. have also reported that GRP possesses exchange activity on R-Ras3 (32). Given the fact that these GEFs all have strong activity towards H-Ras, it is conceivable that the regulation of H-Ras and R-Ras3 activation is highly complex. It is likely that the specificity of GEF and GTPase interactions is dependent on the nature of the external stimuli. Indeed, we have observed that while NGF and bFGF can activate R-Ras3 efficiently, EGF fails to do so. On the contrary, all three trophic factors have been demonstrated to activate Ras in many different cell types. These findings reiterate the critical role of R-Ras3 in transmitting signals important for neuronal differentiation instead of growth. It will be important to identify the GEF that could specifically activate H-Ras, but not R-Ras3, in response to EGF.

We have provided evidence implicating the involvement of R-Ras3 in NGF signaling. In this regard we have shown that the ability of NGF and GRP to induce neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells can be blocked by an R-Ras3 N27 dominant-negative mutant. Since R-Ras3 N27 could potentially sequester multiple GEFs, we cannot definitively rule out that it may also inhibit other G proteins. However, we have demonstrated that it does not inhibit Ras activation by NGF at the concentrations used in various biological assays. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that two other Ras-related members, Rap1A and RalA, are regulated by a different class of GEFs (32). To firmly define a role of R-Ras3 in NGF and GRP signaling, it is therefore necessary to characterize cells derived from mice which are completely null for R-Ras3 expression.

Our investigation into the downstream signaling events responsible for R-Ras3-induced neuronal differentiation has led to some unexpected revelations. Whereas R-Ras3 activates only the PI3-K pathway in NIH 3T3 cells, it mediates the efficient activation of both PI3-K and MAPK pathways in PC12 cells. This is in stark contrast to H-Ras, which has been reported to activate both pathways in either cell line (22, 24). By the use of dominant-negative mutants and pharmacological inhibitors, R-Ras3 was shown to display a certain selectivity in the signaling pathways being used to mediate its biological actions in PC12 cells. While R-Ras3-induced survival is more dependent on PI3-K/Akt, neurite outgrowth is more reliant on the MAPK pathway. It has been demonstrated that the diversity of biological phenotypes elicited by Ras can be attributed to its propensity to activate a host of downstream signaling cascade (6). Similarly, in response to specific trophic factors, R-Ras3 may control neuronal cell fate in the developing CNS by modulating the relative signaling intensity of the PI3-K and MAPK pathways. A detailed examination of the expression and activation state of R-Ras3 and various kinase cascades during mammalian CNS development will shed light on these possibilities.

Our data also imply that R-Ras3 may in fact utilize the neuronally specific Raf isoform, B-Raf, to promote MAPK activation. This would provide a plausible explanation for the cell-type-specific activation of MAPK and is highly reminiscent of the characteristics of Rap1A. Like R-Ras3, Rap1A is unable to activate MAPK in most cell types, with the exception of cells of neuronal lineage (42). Vossler et al. have demonstrated that in PC12 cells, Rap1A also utilizes B-Raf to couple signals derived from cyclic AMP to MAPK activation (42). This is in striking contrast to H-Ras, which can activate the MAPK in a variety of cell types and can bind and activate both B- and c-Raf (27). There are also some recent evidence that there may be cross talk between R-Ras3 and Rap1A. Rebhun et al. and Gao et al. have reported the identification of two GEFs for Rap1A, MR-GEF and RA-GEF-2, in which both possess a Ras-associating (RA) domain. More importantly, these GEFs interact only with the GTP-bound form of R-Ras3 but not with H-Ras (15, 37). Intriguingly, while interaction between R-Ras3 and MR-GEF seems to inhibit Rap1A activation, coexpression of R-Ras3 and RA-GEF-2 leads to the activation of Rap1A. Finally, like Rap1A, R-Ras3 appears to play a role in the sustained phase of MAPK activation upon NGF stimulation (44). Based on all these findings, it is plausible that R-Ras3 and Rap1A are two functionally interacting components of a novel signaling pathway in neuronal differentiation.

To this date, only three members of the Ras subfamily are known to be involved in NGF-induced differentiation of PC12 cells: H-Ras, Rap1A, and Ral (16, 40, 44). Of note, other members such as R-Ras do not display this biological property (39). Interestingly, Ral appears to antagonize neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells, since the Ral exchange factor Rgr attenuates NGF-induced neurite outgrowth, whereas a Ral dominant-negative mutant synergizes with NGF (16). More importantly, whereas activated mutants of H-Ras, Rap1A, and R-Ras3 can promote differentiation in the PC12 system (2, 44), only dominant inhibitory mutants of H-Ras and R-Ras3 block NGF-induced neurite outgrowth (40). The corresponding Rap1A dominant-negative mutant fails to do so (44). One plausible explanation is that while all three GTPases play a role in NGF-induced differentiation, only R-Ras3 and H-Ras are required for neurite outgrowth. On the other hand, Rap1A may be crucial to other aspects of the NGF-induced differentiation, such as the regulation of ion-gated channels (44). We favor the model in which the coordinated activation of these GTPases is necessary for the full differentiation of NGF-treated PC12 cells. At the developmental level, one can envisage that these small GTPases are tightly regulated in a spatial and temporal fashion. Indeed, in this study we have shown that H-Ras and R-Ras3 have distinct patterns of expression in the mammalian CNS, particularly in the cerebellum. The creation of mice possessing homozygous deletions of the R-Ras3 locus will be necessary to understand the physiological role of R-Ras3 during the development of the mammalian nervous system.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Blum (Mt. Sinai) for assisting in the in situ hybridization studies, S. Salton (Mt. Sinai) for help on the PC12 system, D. Felsenfeld (Mt. Sinai) for the dorsal root ganglion culture, M. Rosner (University of Chicago) for H19-7 cells, J. Stone (University of Alberta) for RasGRP plasmids, X. Bustelo (University of Salamanca) for advice on GTP-loading assays, L. Heasley (University of Colorado Health Sciences Center) for the NF-L reporter construct, and A. Okada (Stanford University) for pEGFP-GAP43.

This work was funded by NIH grants CA66654, CA78509, and MH59771. A.C.K. was supported by a NCI predoctoral training grant (CA78207). A.M.C. was a recipient of a Career Scientist Award from the Irma T. Hirschl Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barbacid, M. 1987. ras genes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 56:779-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bar-Sagi, D., and J. R. Feramisco. 1985. Microinjection of the ras oncogene protein into PC12 cells induces morphological differentiation. Cell 42:841-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boguski, M. S., and F. McCormick. 1993. Proteins regulating Ras and its relatives. Nature 366:643-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bos, J. L. 1998. All in the family? New insights and questions regarding interconnectivity of Ras, Rap1 and Ral. EMBO J. 17:6776-6782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bos, J. L. 1989. ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 49:4682-4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell, S. L., R. Khosravi-Far, K. L. Rossman, G. J. Clark, and C. J. Der. 1998. Increasing complexity of Ras signaling. Oncogene 17:1395-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chardin, P., J. H. Camonis, N. W. Gale, L. van Aelst, J. Schlessinger, M. H. Wigler, and D. Bar-Sagi. 1993. Human Sos1: a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Ras that binds to GRB2. Science 260:1338-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffer, P. J., J. Jin, and J. R. Woodgett. 1998. Protein kinase B (c-Akt): a multifunctional mediator of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation. Biochem. J. 335:1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Rooij, J., and J. L. Bos. 1997. Minimal Ras-binding domain of Raf1 can be used as an activation-specific probe for Ras. Oncogene 14:623-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebinu, J. O., D. A. Bottorff, E. Y. Chan, S. L. Stang, R. J. Dunn, and J. C. Stone. 1998. RasGRP, a Ras guanyl nucleotide-releasing protein with calcium- and diacylglycerol-binding motifs. Science 280:1082-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrhardt, G. R., K. B. Leslie, F. Lee, J. S. Wieler, and J. W. Schrader. 1999. M-Ras, a widely expressed 29-kD homologue of p21 Ras: expression of a constitutively active mutant results in factor-independent growth of an interleukin-3-dependent cell line. Blood 94:2433-2444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fam, N. P., W. T. Fan, Z. Wang, L. J. Zhang, H. Chen, and M. F. Moran. 1997. Cloning and characterization of Ras-GRF2, a novel guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Ras. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:1396-1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farnsworth, C. L., N. W. Freshney, L. B. Rosen, A. Ghosh, M. E. Greenberg, and L. A. Feig. 1995. Calcium activation of Ras mediated by neuronal exchange factor Ras-GRF. Nature 376:524-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frech, M., J. John, V. Pizon, P. Chardin, A. Tavitian, R. Clark, F. McCormick, and A. Wittinghofer. 1990. Inhibition of GTPase activating protein stimulation of Ras-p21 GTPase by the Krev-1 gene product. Science 249:169-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao, X., T. Satoh, Y. Liao, C. Song, C. D. Hu, K. Kariya Ki, and T. Kataoka. 2001. Identification and characterization of RA-GEF-2, a Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor that serves as a downstream target of M-Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 276:42219-42225. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Goi, T., G. Rusanescu, T. Urano, and L. A. Feig. 1999. Ral-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factor activity opposes other Ras effectors in PC12 cells by inhibiting neurite outgrowth. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:1731-1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heimer, L. 1995. The human brain, 2nd ed. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- 18.Johnson, L., D. Greenbaum, K. Cichowski, K. Mercer, E. Murphy, E. Schmitt, R. T. Bronson, H. Umanoff, W. Edelmann, R. Kucherlapati, and T. Jacks. 1997. K-ras is an essential gene in the mouse with partial functional overlap with N-ras. Genes Dev. 11:2468-2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimmelman, A., T. Tolkacheva, M. V. Lorenzi, M. Osada, and A. M. Chan. 1997. Identification and characterization of R-ras3: a novel member of the RAS gene family with a non-ubiquitous pattern of tissue distribution. Oncogene 15:2675-2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimmelman, A. C., M. Osada, and A. M. Chan. 2000. R-Ras3, a brain-specific Ras-related protein, activates Akt and promotes cell survival in PC12 cells. Oncogene 19:2014-2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura, K., S. Hattori, Y. Kabuyama, Y. Shizawa, J. Takayanagi, S. Nakamura, S. Toki, Y. Matsuda, K. Onodera, and Y. Fukui. 1994. Neurite outgrowth of PC12 cells is suppressed by wortmannin, a specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 269:18961-18967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klesse, L. J., K. A. Meyers, C. J. Marshall, and L. F. Parada. 1999. Nerve growth factor induces survival and differentiation through two distinct signaling cascades in PC12 cells. Oncogene 18:2055-2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lacal, J. C., and S. A. Aaronson. 1986. Activation of ras p21 transforming properties associated with an increase in the release rate of bound guanine nucleotide. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6:4214-4220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, B. Q., D. Kaplan, H. F. Kung, and T. Kamata. 1992. Nerve growth factor stimulation of the Ras-guanine nucleotide exchange factor and GAP activities. Science 256:1456-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, J., and R. J. Wurtman. 1998. Nerve growth factor stimulates diacylglycerol de novo synthesis and phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis in pheochromocytoma cells. Brain Res. 803:44-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Louahed, J., L. Grasso, C. De Smet, E. Van Roost, C. Wildmann, N. C. Nicolaides, R. C. Levitt, and J. C. Renauld. 1999. Interleukin-9-induced expression of M-Ras/R-Ras3 oncogene in T-helper clones. Blood 94:1701-1710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marais, R., Y. Light, H. F. Paterson, C. S. Mason, and C. J. Marshall. 1997. Differential regulation of Raf-1, A-Raf, and B-Raf by oncogenic Ras and tyrosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 272:4378-4383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marshall, C. J. 1995. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell 80:179-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsumoto, K., T. Asano, and T. Endo. 1997. Novel small GTPase M-Ras participates in reorganization of actin cytoskeleton. Oncogene 15:2409-2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melton, D. A., P. A. Krieg, M. R. Rebagliati, T. Maniatis, K. Zinn, and M. R. Green. 1984. Efficient in vitro synthesis of biologically active RNA and RNA hybridization probes from plasmids containing a bacteriophage SP6 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:7035-7056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oestreicher, A. B., P. N. De Graan, W. H. Gispen, J. Verhaagen, and L. H. Schrama. 1997. B-50, the growth associated protein-43: modulation of cell morphology and communication in the nervous system. Prog. Neurobiol. 53:627-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohba, Y., N. Mochizuki, S. Yamashita, A. M. Chan, J. W. Schrader, S. Hattori, K. Nagashima, and M. Matsuda. 2000. Regulatory proteins of R-Ras, TC21/R-Ras2, and M-Ras/R-Ras3. J. Biol. Chem. 275:20020-20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okada, A., R. Lansford, J. M. Weimann, S. E. Fraser, and S. K. McConnell. 1999. Imaging cells in the developing nervous system with retrovirus expressing modified green fluorescent protein. Exp. Neurol. 156:394-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osada, M., T. Tolkacheva, W. Li, T. O. Chan, P. N. Tsichlis, R. Saez, A. C. Kimmelman, and A. M. Chan. 1999. Differential roles of Akt, Rac, and Ral in R-Ras-mediated cellular transformation, adhesion, and survival. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:6333-6344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plantefaber, L. C., and R. O. Hynes. 1989. Changes in integrin receptors on oncogenically transformed cells. Cell 56:281-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quilliam, L. A., A. F. Castro, K. S. Rogers-Graham, C. B. Martin, C. J. Der, and C. Bi. 1999. M-Ras/R-Ras3, a transforming ras protein regulated by Sos1, GRF1, and p120 Ras GTPase-activating protein, interacts with the putative Ras effector AF6. J. Biol. Chem. 274:23850-23857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rebhun, J. F., A. F. Castro, and L. A. Quilliam. 2000. Identification of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) for the Rap1 GTPase. Regulation of MR-GEF by M-Ras-GTP interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 275:34901-34908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reeben, M., T. Neuman, J. Palgi, K. Palm, V. Paalme, and M. Saarma. 1995. Characterization of the rat light neurofilament (NF-L) gene promoter and identification of NGF and cAMP responsive regions. J. Neurosci. Res. 40: 177-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rey, I., P. Taylor-Harris, H. van Erp, and A. Hall. 1994. R-ras interacts with rasGAP, neurofibromin and c-raf but does not regulate cell growth or differentiation. Oncogene 9:685-692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szeberenyi, J., H. Cai, and G. M. Cooper. 1990. Effect of a dominant inhibitory Ha-ras mutation on neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:5324-5332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Umanoff, H., W. Edelmann, A. Pellicer, and R. Kucherlapati. 1995. The murine N-ras gene is not essential for growth and development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1709-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vossler, M. R., H. Yao, R. D. York, M. G. Pan, C. S. Rim, and P. J. Stork. 1997. cAMP activates MAP kinase and Elk-1 through a B-Raf- and Rap1-dependent pathway. Cell 89:73-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]