Abstract

Transcriptional regulation by nuclear receptors is controlled by the concerted action of coactivator and corepressor proteins. The product of the thyroid hormone-regulated mammalian gene hairless (Hr) was recently shown to function as a thyroid hormone receptor corepressor. Here we report that Hr acts as a potent repressor of transcriptional activation by RORα, an orphan nuclear receptor essential for cerebellar development. In contrast to other corepressor-nuclear receptor interactions, Hr binding to RORα is mediated by two LXXLL-containing motifs, a mechanism associated with coactivator interaction. Mutagenesis of conserved amino acids in the ligand binding domain indicates that RORα activity is ligand-dependent, suggesting that corepressor activity is maintained in the presence of ligand. Despite similar recognition helices shared with coactivators, Hr does not compete for the same molecular determinants at the surface of the RORα ligand binding domain, indicating that Hr-mediated repression is not simply through displacement of coactivators. Remarkably, the specificity of Hr corepressor action can be transferred to a retinoic acid receptor by exchanging the activation function 2 (AF-2) helix. Repression of the chimeric receptor is observed in the presence of retinoic acid, demonstrating that in this context, Hr is indeed a ligand-oblivious nuclear receptor corepressor. These results suggest a novel molecular mechanism for corepressor action and demonstrate that the AF-2 helix can play a dynamic role in controlling corepressor as well as coactivator interactions. The interaction of Hr with RORα provides direct evidence for the convergence of thyroid hormone and RORα-mediated pathways in cerebellar development.

Nuclear receptors are transcription factors that control essential developmental and physiological pathways (34). The nuclear receptor superfamily consists of receptors that bind steroid hormones (such as estradiol and cortisone), nonsteroidal ligands (such as retinoic acid and thyroid hormone), diverse products of lipid metabolism (such as fatty acids and bile acids), as well a large group of receptors whose discoveries have preceded that of their ligands, known as orphan receptors (14). Members of this superfamily control the expression of their target genes in a ligand-regulated fashion through interaction with coregulator proteins (16). Coregulators and associated cofactors can either repress or activate gene transcription through the recruitment of diverse functional domains and enzymatic activities to the promoters of target genes (37). Corepressor and coactivator binding to nuclear receptors is thought to be mutually exclusive and regulated by ligand binding, making coregulator exchange a key feature in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors (16).

The ligand-binding domain (LBD) of nuclear receptors mediates the ligand-dependent transactivation function through activation function 2 (AF-2), which serves as a binding surface for a diverse set of coactivators (12). AF-2 is comprised of a hydrophobic cleft formed by 3 (H3, H5, and H6) of the 11 helices constituting the LBD and a short amphipathic alpha-helix referred to as the AF-2 helix (8). AF-2-dependent coactivators encode one or more signature motifs of a consensus sequence LXXLL (where L is a leucine and X is any amino acid) which also form amphipathic alpha-helices (20). The LXXLL helix fits into the hydrophobic cleft of a liganded receptor and this interaction is stabilized by the presence of the AF-2 helix (39, 46, 57). Receptor-specific utilization of LXXLL-containing motifs is dictated by adjacent amino acid residues (9, 33, 36), and peptides containing such motifs have been shown to antagonize the activity of nuclear receptors with great specificity (3, 40).

Corepressors such as N-CoR and SMRT have an autonomous repression domain and interact with unliganded nonsteroid receptors (4, 7, 19, 22, 30, 32, 44, 47, 59) as well as to antagonist-bound steroid receptors (25, 31, 48). Like coactivators, these proteins encode an extended amphipathic helix whose sequence contains the residues ΦXXΦΦ (where Φ is a hydrophobic residue and X is any amino acid) (23, 38, 41). In a manner analogous to the LXXLL-containing motifs, mutational analysis has suggested that this extended helix also makes contacts with residues in the hydrophobic pocket but is not dependent on the charged clamp and the AF-2 helix (38, 41). Indeed, deletion of the AF-2 helix enhances corepressor binding (4), suggesting that the helix does not play an active role in nuclear receptor-corepressor recognition.

RORα (retinoic acid receptor related orphan receptor α) (NR1F1) is a constitutively active orphan nuclear receptor that plays a vital role in cerebellar development, lipid metabolism, and neoplasia (reviewed in reference 14). Disruption of the rora gene in mice leads to the staggerer phenotype, which is characterized by depletion of Purkinje cells and severe cerebellar ataxia (10, 18, 35, 50). Transcription of RORα target genes can be regulated by passive repression. This mechanism involves competition for binding to the same response element with Rev-erbAα (NR1D1) and RVR (NR1D2) orphan nuclear receptors which lack an AF-2 helix (11, 13, 43). Repression of RORα-regulated gene expression may be functionally significant, as generation of a null mutation in the gene encoding Rev-ErbAα results in delayed Purkinje cell differentiation, suggesting that inhibiting the expression of RORα-induced genes is required for maturation of these cells (5). A third factor known to be important for cerebellar development is thyroid hormone (T3). T3 deficiency affects a number of developmental processes in neonatal cerebellum, including cell migration, differentiation, and synaptogenesis (28). Thus, cerebellar development is likely to be regulated through the cross talk of T3R, RORα, and Rev-ErbAα nuclear receptors.

A search for T3-regulated genes in the cerebellum resulted in the isolation of the rat hairless (hr) gene (52). hr is expressed at high levels shortly after birth and is a direct target gene of T3, as it has a potent T3 response element and is rapidly induced even in the absence of protein synthesis (52, 54). Multiple mutant hr alleles have been described that result in the hairless phenotype both in mice (51) and in humans (1, 6). The hr gene product (Hr) has been shown to be a corepressor that mediates transcriptional repression by unliganded T3R (42, 53). Hr interacts with histone deacetylases and localizes to matrix-associated deacetylase bodies, indicating that the mechanism of Hr-mediated repression is similar to those of other corepressors (42).

Given the potential cross talk between T3R and RORα in cerebellar development, we investigated whether Hr was a common cofactor of these regulatory pathways. Here we show that Hr is a potent repressor of RORα transcriptional activity and that the specificity of the interaction between Hr and RORα is dictated by the primary structure of the AF-2 helix. These results define a novel role for the AF-2 helix in corepressor/nuclear receptor interactions and suggest that Hr, RORα, and T3R belong to a common ligand-based developmental regulatory network.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast two-hybrid assay.

The yeast two-hybrid assay was performed as previously described (21, 53). pLexA-Hr 568-1207, pLexA-Hr 782-1207 and pLexA-Hr 568-784 have been described previously (42, 53). pVP16-RORα was constructed by excising the RORα LBD from pCMXGAL4hRORαLBD by digestion with EcoRI and BamHI and inserting the fragment into the EcoRI-BamHI sites of pVP16 (21).

Plasmid construction.

pCMX-VP16hRORα1 was made as follows: pCMX-hRORα1, described elsewhere (15), was digested with NotI/BamHI restriction enzymes, yielding a 1.7-kb fragment (including amino acids 22 to 523) and cloned into the NotI/BamHI sites of pCMXVP16N containing a NotI linker. pCMX-Flag-hRORα1 was made by introducing by PCR EcoRI and BamHI sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, of RORα (amino acids 1 to 523) and cloning into pCMX-FLAG vector. pCMXGAL4hRORαLBD, which encodes amino acids 270 to 523, was constructed by cloning in frame an EcoRV/BamHI fragment from pCMXhRORα1 downstream of the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (DBD) sequence. pKShRORα1LBD was constructed by cloning the same EcoRV/BamHI fragment into pBluescript KS II (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). pKS-RORαLBD was used as a template for site-directed mutagenesis, generating the following LBD mutants: C288F, W320A, C323A, E329A, A330T, V335R, K339A, I353A, K357A, L361F, V364G, F365Y, M368A, A371G, Y380A, D382V, G395D, F399Y, H484A, L488A, F491A, F503A, L506R, Y507A, E509K, and L510A. Mutations were verified by sequencing followed by subcloning of the EcoRV-BamHI fragment into the pCMX-hRORα1 backbone. pCMX-RORαΔAF2 was generated by mutating E509A, L510A, F511A, and T512A residues of helix 12. pCMX-RORαV335R/ΔAF2, K339A/ΔAF2, I353A/ΔAF2, and K357A/ΔAF2 were generated by subcloning a 509-bp XbaI/BamHI fragment encoding the mutated H12 into the pCMX-RORα cleft mutant backbone.

The mouse RORβ and RORγ cDNAs were isolated from a brain and skeletal muscle λgt11 cDNA library (Clonetech), respectively. Both pCMXmRORβ and pCMXmRORγ were generated by subcloning EcoRI fragments containing the full-length cDNAs for both RORβ and RORγ, respectively, into pCMX expression vector.

pRK5-myc-rhr has been described elsewhere (42). pRK5-myc-rhr was used as a template for site-directed mutagenesis using Pfu polymerase (Stratagene), generating Hrm1 (L586A), Hrm2 (L589A, L590A), Hrm3 (L781A, L782A), Hrm4 (I820A, I821A), Hrm5 (L589A, L590A, L781A, L782A), Hrm6 (L586A, L781A, L782A), Hrm7 (L589A, L591A, I820A, I821A), and Hrm8 (L781A, L782A, I820A, I821A). These and all subsequent mutations were verified by sequencing. To generate pCMXGAL4-Hr568-1207, a 2.21-kb HindIII fragment from rat Hr was blunted using Klenow, and BamHI linkers were added and ligated into the BamHI site pCMXGAL4. pCMXGAL4-Hr568-784 was constructed by digesting pCMXGAL4-Hr568-1207 with NheI, isolating the vector fragment, and religating, resulting in the deletion of the Hr sequences downstream of the NheI site at position 2732 of the cDNA. pCMX-HrRID encompassing amino acids 568 to 784 was generated by adding by PCR Asp718 and BamHI restriction sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends of this region, respectively, followed by subcloning into the pCMX backbone.

pCMXhRARα and pCMXhRXRα were described elsewhere (56). pCMXhRARα-R was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis using Pfu polymerase of pCMXhRARα template, introducing a 5-amino-acid change in the AF-2 helix: I410Y, Q411K, M413L, L414F, and E414T. These were verified by sequencing, followed by subcloning of a 286-bp SmaI fragment encoding the mutations into the pCMXhRARα backbone. Reporter constructs ROREα23TKLuc, UAS2TKLuc, and TREpal3TKLuc were previously described (15, 55). pCMX-HA-RARα-R and pCMX-HA-RARα were constructed by the following method. Hemagglutinin (HA) tag (CYPYDVPDYASLEF)-annealed oligonucleotides flanked by ClaI and EcoRI at the 5′ and 3′ end, respectively, were cloned between the ClaI/EcoRI sites of pCMX, yielding pCMX-HA. Amino acids 2 to 462 of pCMXhRARα and pCMXhRARα-R was amplified by PCR. EcoRI and BamHI sites were introduced at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, followed by subcloning into the pCMX-HA vector.

The receptor interacting domains (RID) of the steroid receptor coactivator (SRC) family members were amplified by PCR using Pfu polymerase and oligonucleotides that introduce a BamHI and an EcoRI site on the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, followed by subcloning into the BamHI/EcoRI sites of the pGEX2T vector. pGEX2TmSRC1aRID includes amino acids 565 to 787, pGex2TmGRIP1RID includes amino acids 563 to 767, and pGEX2Tmp/CIPRID includes amino acids 547 to 785. pRK5myc-rHr and pRK5myc-rhrm1-m8 were digested with HindIII and SacI restriction enzymes, generating an 891-bp fragment, encoding amino acids 568 to 864; blunted using Klenow; and ligated into pGEX2T vector digested by SmaI, yielding pGEX2T-rHr568-784 and pGEX2T-rHrm1-m8. The RID of SMRT (amino acids 1080 to 1495) was amplified by PCR and cloned into the BamHI-EcoRI site of pGEX-2T vector, yielding pGEX2T-SMRTRID (provided by M. Latreille, McGill University).

Protein expression and GST pull-down assays.

The various bait constructs were transformed in Escherichia coli DH5α. GSTSRC1aRID, glutathione S-transferase (GST)-GRIP1RID, GST-P/CIPRID, GST-Hr, GST-Hrm1-m8, and GST-SMRTRID protein expression was induced with 0.5 mM isopropylthiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 37°C for 3 h. Bacterial extracts were prepared by sonication in a 1% Triton-X phosphate-buffered saline solution. The amount of bacterial extract used in each experiment was determined based on a Coomassie stained sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-10% polyacrylamide gel, used to determine equal protein expression. The bacterial extracts were bound to 30 μl of a 50% slurry of glutathione-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia Biotech) in NET-N buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1.0% TritonX-100, 1 μM leupeptin, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) for 30 min of mild rotation at 4°C. The beads were then washed twice in GST-binding buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 150 mM KCl, 0.1% 3-{[3-cholamidopropyl]dimethyl-ammonio}-1-propanesulfonate [CHAPS], bovine serum albumin [20 μl/ml], 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM leupeptin). Five microliters of in vitro-translated [35S]methionine-labeled proteins, using TNT rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega, Madison, Wis.), was added to the beads in a final volume of 150 μl of GST-binding buffer and incubated for 1 h 30 min at 4°C with mild rotation. The complexes were washed twice in GST-binding buffer. They were then resuspended in 1× SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5 min prior to loading on an SDS-10% polyacrylamide gel. The gels were fixed in 25% isopropanol/10% acetic acid, followed by treatment with the fluorographic reagent Amplify (Amersham Life Science), dried and exposed.

Cell culture and transient transfection.

Cos-1 cells obtained from the American Type Culture Collection were cultured in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium containing penicillin (25 U/ml), streptomycin (25 U/ml), and 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C with 5% CO2. Twenty-four hours prior to transfection the cells were split and seeded in 12-well plates. The cells were transfected with FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics), following protocol supplied by the manufacturer, and harvested 24 h after transfection. Typically, 0.05 μg of receptor plasmid, 0.5 μg of pRK5-mycrhr, 0.5 μg of reporter plasmid, and 0.25 μg of internal control pCMVβGal were transfected per well. For the mammalian two-hybrid assay, 0.2 μg of pCMXVP16hRORα1, 0.01 μg of pCMX-GAL4-rHr, 0.5 μg of pCMX-UAS2cTKLuc, 0.25 μg pof CMVβGal, and pBluescript KS plasmid were added to a total of 1 μg DNA per well. For transfection of RARα/RARα-R, the cells were seeded in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% charcoal-dextran-treated fetal calf serum 24 h prior to transfection. Four hours after transfection, the cells were washed twice with 1× phosphate-buffered saline and fresh medium was added containing ethanol (vehicle) or all-trans retinoic acid (at-RA) to final concentration of 10−8 M. Cells were then harvested 16 h later and assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase. Per well, 0.05 μg of pCMXhRARα/hRARα-R and pCMXhRXRα, 0.25 μg of pRK5-mycrhr, 0.5 μg of TREpal3TKLuc, and 0.25 μg of pCMVβGal were transfected.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

Cos-1 cells were transiently transfected with 5 μg of pCMX-FlagRORα, pCMX-HAhRARα, pCMX-HAhRARα-RpRK5-mycrHr as described above. Cells were lysed in IP buffer (1% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete Mini EDTA-free; Roche Diagnostics). Lysates were incubated with either Flag antibody (Sigma), HA antibody (Upstate Biotechnology), or Hr antibody (MD9-Hr) overnight at 4°C, with gentle rotation. Proteins were collected on either protein A- or protein G-Sepharose for 3 h at 4°C with mild rotation and then washed three times with low-salt buffer (1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]). Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblotted with Flag antibody, HA antibody (Covance), or Hr antibody. Proteins were visualized with the POD chemiluminescence kit following manufacturer's instructions (Roche Diagnostics). Immunoblotting for detection of Hr mutant proteins was similarly done using lysates from transiently transfected Cos-1 cells and immunoblotting with Hr antibody.

RESULTS

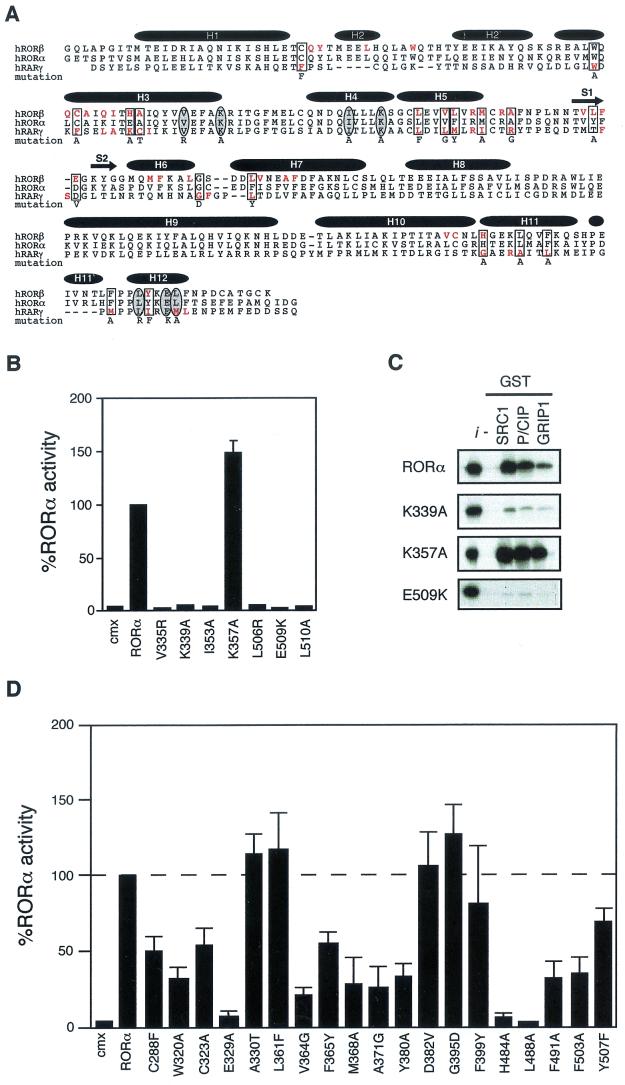

RORα shares functional and structural determinants with classic nuclear receptors. The amino acid residues involved in forming the hydrophobic cleft required for coactivator interaction are highly conserved among members of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Formation of this hydrophobic cleft is also dependent on the AF-2 helix. Recently, resolution of the crystal structure of RORβ LBD demonstrated that the members of the ROR family share the same canonical fold described for other nuclear receptors, with an additional 2 alpha-helices (49). The presence of a functional ligand binding pocket (LBP), a hydrophobic cleft and AF-2 helix at the surface of RORβ LBD is maintained. We first used site-directed mutagenesis to assess the involvement of these determinants in RORα constitutive transcriptional activity and their interaction with the three members of the SRC family of coactivators. Residues were targeted according to previous functional analyses of nuclear receptor/coactivator interaction demonstrating the importance of specific conserved residues in these interactions (Fig. 1A ). As shown in Fig. 1B, mutation of residues participating in the formation of the hydrophobic cleft resulted in complete loss of RORα transcriptional activity when assayed by transient transfection with a reporter plasmid consisting of the monomeric RORE linked to the basal thymidine kinase promoter. The loss of RORα transcriptional activity is correlated with loss of interaction with members of the SRC family of coregulators as measured in a GST pull-down assay (Fig. 1C). These results extend observations previously made using mutant Gal4DBD-RORα chimeras and GRIP-1 (2) to the native RORα and all members of the SRC family. RORα differs from other nuclear receptors with respect to the importance of K357 in H4. This residue has been shown to be required for the formation of a functional coactivator surface (12). Mutation of K357A does not affect RORα transcriptional activity (Fig. 1B), and interaction with SRC family members remains unhindered (Fig. 1C). This is in agreement with data provided by the RORβ crystal structure, in which this residue was not shown to make contact with SRC LXXLL helix.

FIG.1.

RORα shares common structural and functional determinants with classic nuclear receptors. (A) Primary sequence of RORβ, RORα, and RARγ ligand binding domains. Amino acids involved in the LBP identified by crystallographic analysis are highlighted in red. Amino acids essential for AF-2 activity and known to participate in ligand binding targeted for site-directed mutagenesis are circled and boxed, respectively. The respective amino acid change is indicated below the sequence. The secondary structure is represented by black bars for the α-helices and arrows for the β-sheets. (B) RORα hydrophobic cleft mutants (V335R, K339A, and I353A) and AF-2 helix mutants (L506R, E509K, and L510A) are transcriptionally inactive in transfected Cos-1 cells, with the exception of the cleft mutant K357A. Normalized values are calculated in terms of percent RORα activity with respect to wild type. These results are the average of three independent experiments. (C) Binding of RORα and hydrophobic cleft (K339A, K357A) and AF-2 helix (E509K) mutants to SRC proteins. GST-SRC1aRID, GST-p/CIPRID, and GST-GRIP1RID fusion proteins were coupled to Sepharose beads incubated with 35S-labeled RORα, RORαK339A, RORαK357A, and RORαE509K. The input lane (i) represents 10% of total lysate included in the binding reaction. (D) Cos-1 cells were cotransfected with RORα LBP mutants and ROREα23-TkLuc reporter. Normalized luciferase values are expressed as percent activity with respect to wild-type RORα. These results are the average of three independent experiments.

X-ray structure analyses complemented by extensive mutational studies of nuclear receptor LBDs have defined the determinants required for high-affinity ligand binding (reviewed in reference 58). By analogy with data derived from analysis of RARγ and RORβ, we have generated a set of RORα mutants carrying point mutations that, in the context of RARγ and RORβ, either abolish or significantly diminish the ability to recognize their cognate ligands, thus hampering their ability to transactivate (Fig. 1A). As seen in Fig. 1D, for 12 of 19 mutant receptors transcriptional activity was diminished by more than 50%. All mutant receptors were expressed at similar levels as measured by Western blot analysis (data not shown). These results strongly suggest that the transcriptional activity of RORα is regulated by a ligand present endogenously in cultured cells. This data also lends support to the differences within the ligand binding pocket (LBP) of ROR family members. Particularly, residues A330, L361, and F399 are required for ligand binding for both RORβ and RARγ (Fig. 1A) but are not required for ligand binding by RORα, leading to transactivation levels equivalent to wild type (Fig. 1D). In general, RORα, RORβ, and RORγ likely share the same overall structure, but significant differences within the LBP would allow each receptor to discriminate their respective ligands.

Hr is a repressor of orphan nuclear receptor RORα.

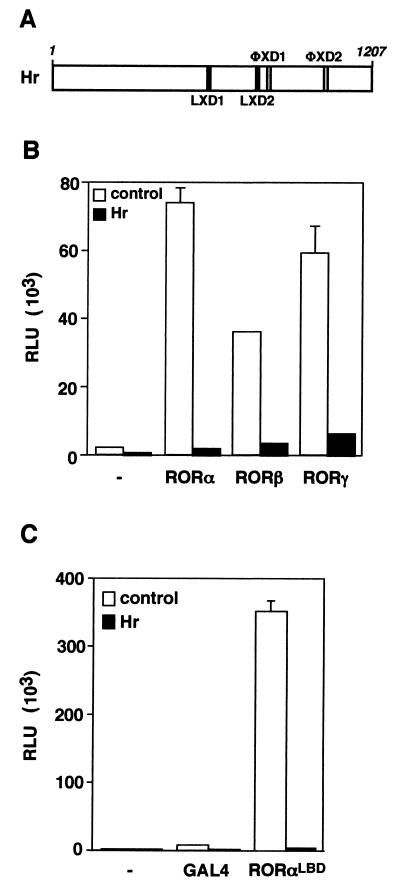

Hr is a newly identified nuclear receptor corepressor that has been shown to interact specifically with T3R (42, 53). While the Hr protein does not share sequence identity with previously characterized nuclear receptor corepressors, it encodes four nuclear receptor interaction motifs (Fig. 2A). Two motifs have the coactivator LXXLL-containing consensus sequence, and two include the sequence ΦXXΦΦ, which is thought to mediate corepressor interaction. Since RORα and T3R may be part of a common regulatory pathway controlling cerebellar development, we investigated whether Hr could also modulate RORα transcriptional activity. As shown in Fig. 2B, coexpression of Hr and RORα leads to nearly complete inhibition of the potent constitutive transcriptional activity displayed by RORα. Given the high degree of identity and functional similarity between members of the ROR family (14), we next tested whether Hr could inhibit the activity of the RORβ and γ isoforms. Hr antagonizes the transcriptional activity of RORβ and RORγ (Fig. 3B), indicating that Hr is a corepressor of all ROR isoforms and that Hr interaction determinants are likely conserved within the family.

FIG. 2.

Hr represses ROR transcriptional activation. (A) Schematic representation of the Hr protein containing two LXXLL motifs (LXD1 and LXD2) and two ΦXXΦΦ motifs (ΦxD1 and ΦxD2). The numbers above indicate amino acid positions. (B) Hr represses RORα, -β, and -γ constitutive transcriptional activities. Cos-1 cells were cotransfected with hRORα, mRORβ, mRORγ, and ROREα23-TKLuc in the absence (open bars) or the presence (black bars) of Hr. (C) Hr represses RORα activity on a heterologous promoter through its LBD. Schematic representation of the Gal4-RORαLBD. Numbers above indicate the amino acid positions. Cos-1 cells were cotransfected with Gal4-RORαLBD, Hr, and UAS2TKLuc. Normalized values are presented in relative luciferase units (RLU). A representative experiment of three independent experiments is shown. Error bars represent the standard deviation between duplicate samples.

FIG. 3.

Determinants involved in Hr-RORα interaction. (A) A domain of Hr encoding two LXXLL motifs is sufficient for interaction with RORα. Results of yeast two-hybrid assay with Hr deletion derivatives. The indicated Hr fragments were expressed as fusion proteins with the LexA DBD and tested for interaction with the RORα LBD fused with the VP16 activation domain. +, survival in the absence of histidine. (B) Cos-1 cells were cotransfected with Gal4-Hr568-1207, Gal4-Hr568-784, VP16-RORα, and UAS2TKLuc. Normalized values are presented. (C) The AF-2 helix inhibits Hr binding to RORα in vitro. In vitro-translated and labeled RORα and RORαΔAF-2 were assayed for interaction with GST-SRC1RID or GST-Hr568-784 coupled to Sepharose beads. The input lane (i) represents 10% of total lysate included in each binding reaction. (D) Hr interacts with RORα in vivo. Cos-1 cells were transiently transfected with pCMX-FlagRORα and pRk5-mycHr. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with Hr antibody, Flag antibody, or rabbit or mouse immunoglobulin G (as negative controls), followed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag. The input lane (i) represents 20% of lysate used in each IP.

The presence of nuclear receptor interaction motifs within Hr and the ability to repress transcriptional activity by all ROR isoforms indicated that Hr might interact with the ROR LBD. To assess this possibility, we first generated a chimeric protein in which the DNA binding domain of the yeast Gal4 transcription factor was linked to the LBD of RORα (Fig. 2C). When transiently expressed in Cos-1 cells with a Gal4UASLuc reporter plasmid, the Gal4-RORαLBD chimera displays constitutive transcriptional activity as potent as the activity generated by the native receptor. Similarly, the transcriptional activity of the Gal4-RORαLBD chimera is completely abolished by Hr, demonstrating that repression is mediated through the LBD and is independent of the reporter gene used in the assay.

We next tested whether the region of Hr encoding the nuclear receptor interaction motifs was sufficient to promote Hr/RORα interaction. Figure 3A depicts the result of a yeast two-hybrid experiment in which fragments of Hr were fused with the LexA DBD and the activation function of VP16 was fused to RORα. Both the carboxy-terminal fragment (Hr568-1207) and an internal fragment (Hr568-784) interact with RORα. Surprisingly, Hr568-784 contains the two coactivator interaction LXXLL motifs, while the noninteracting fragment (amino acids 782 to 1207) contains the two corepressor motifs previously shown to mediate interaction with T3R (42). Analysis of Hr-ROR interaction in a mammalian two-hybrid experiment gave similar results (Fig. 3B). Fragments of the Hr protein were fused to the Gal4 DBD while the activation function of VP16 was fused to RORα. The resulting constructs were cotransfected in Cos-1 cells together with a Gal4 upstream activation sequence reporter and interaction was measured by luciferase assay. As shown, both the carboxy-terminal Hr fragment (amino acids 568 to 1207) and the smaller internal fragment (amino acids 568 to 784) interact with RORα in mammalian cells. These results indicate that it may be the coactivator binding motifs and not the corepressor interaction motifs that play a role in Hr-RORα interaction.

Direct interaction between RORα and Hr was tested using GST pull-down experiments. As shown in Fig. 3C, native RORα interacts very weakly with Hr but strongly with SRC-1. However, it has been observed that interaction between nuclear receptors and corepressors such as SMRT and N-CoR is enhanced upon inactivation of the AF-2 helix (4). We thus generated an AF-2 helix-deficient form of RORα and tested its ability to bind to Hr in vitro. The AF-2 helix-deficient RORα mutant displays a complete reversal in binding activity: strong interaction with Hr and a total loss of its ability to bind SRC-1. We next tested whether Hr interacts with RORα in vivo. As shown in Fig. 3D, Flag-tagged RORα coimmunoprecipitates with Hr in transiently transfected Cos-1 cells. Although the AF-2 helix hinders Hr binding in vitro, this is not the case in vivo, where interaction between RORα and Hr occurs. This suggests that a third component required for Hr binding is missing in the in vitro system. One explanation for this phenomenon is that posttranslational modification of RORα may influence the dynamics of the AF-2 helix, promoting interaction with Hr. There are three species detected by the Flag antibody, which may represent posttranslationally modified forms of RORα. A second possibility is that a third protein acting as a bridging factor is required as a ternary partner for RORα-Hr interaction.

Repression of RORα activity by Hr is dependent on two LXXLL motifs.

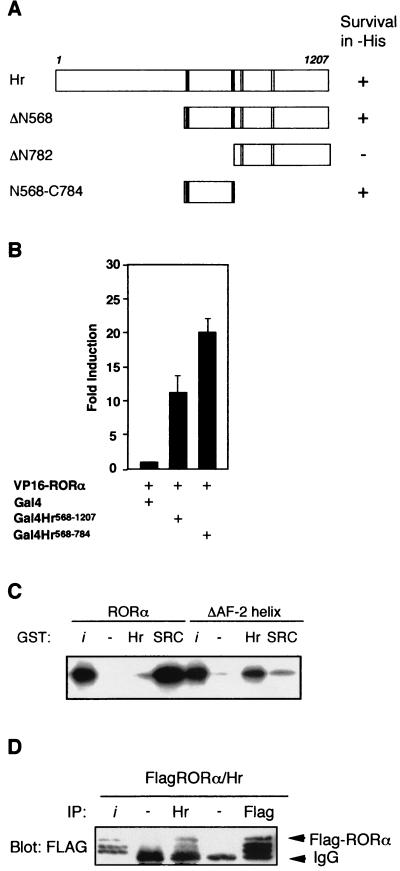

While the above results indicate that Hr-RORα binding is mechanistically similar to that of a classic nuclear receptor-corepressor interaction, based on our deletion analysis (Fig. 3A), its interaction with RORα appears to be dictated through coactivator-like recognition motifs. To test this hypothesis, we introduced a series of point mutations in three of the nuclear receptor recognition motifs (Fig. 4A) and assayed the ability of the mutated Hr to repress RORα transcriptional activity in Cos-1 cells. All mutants were expressed at similar levels as shown by the Western blot (Fig. 4B, lower panel). As shown in Fig. 4B (upper panel), mutations of the proximal leucine residue (Hrm1) and two distal leucine residues (Hrm2) in the first LXXLL motif leads to an ∼50% loss in Hr repressive activity. Likewise, mutation of the two distal leucine residues in the second LXXLL motif (Hrm3) also results in a sharp diminution of Hr activity. In contrast, mutations within the ΦXXΦΦ motif (Hrm4) have no deleterious effect on Hr function. However, the ability of Hr to repress RORα activity was completely lost when combinations of mutations in both LXXLL were introduced in Hr (Hrm5 and Hrm6). Combinations of mutations in either LXXLL motif together with the ΦXXΦΦ motif (Hrm7 and Hrm8) resulted in Hr mutants with activity similar to that of the individual LXXLL mutants. Finally, the GST pull-down experiment shows that the levels of in vivo activity displayed by Hr mutants correlate well with their RORα binding activity in vitro (Fig. 4C). Unexpectedly, these results demonstrate that the repressive activity of Hr is dependent on the presence of the two LXXLL motifs rather than the ΦXXΦΦ motifs.

FIG. 4.

Hr repression requires intact LXXLL motifs. (A) Schematic representation of the Hr protein. Hrm1-Hr-m8 encoding point mutations of the LXD1, LXD2, and ΦXD1 motifs are represented. (B) Hr and Hrm1-Hrm8 expression plasmids were cotransfected into Cos-1 cells with RORα and ROREα23-TkLuc reporter, as shown at the top of the panel. Normalized values are expressed as a percentage of RORα activity. Results are the average of three independent experiments. Cos-1 cells were transiently transfected with pRK5-mycHr wild-type and mutant expression vectors, as shown at the bottom of the panel. Extracts were immunoblotted with Hr antibody. (C) Hr repression correlates with RORα binding. GST-Hr and GST-Hrm1-Hrm8 were coupled to Sepharose beads and incubated with 35S-labeled RORαΔAF2 mutant, in a GST pull-down assay. The input lane (i) represents 10% of total lysate included in each binding reaction. (D) Hr interaction is not mediated through residues of the hydrophobic cleft. 35S-labeled hydrophobic cleft mutants (V335R, K339A, I353A, K357A)/ΔAF2 were assayed for interaction with GST-Hr in a pull-down assay as above. (E) HrRID does not compete with endogenous coactivators. Cos-1 cells were transiently transfected with RORα, Hr and HrRID expression plasmids. Normalized values are expressed as relative luciferase units (RLU). Error bars represent the standard deviation between duplicate samples. This is one representative experiment of three.

Since Hr binds to RORα via LXXLL motifs, a mechanism shared by coactivators such as SRC-1, repression of RORα activity by Hr may occur by occluding coactivator binding. To test whether Hr LXXLL motifs and SRC LXXLL motifs share the same determinants at the surface of the RORα LBD, we generated constructs containing both mutations in the hydrophobic cleft and the AF-2 helix and tested their ability to interact in vitro with Hr in a GST pull-down assay (Fig. 4D). Mutation of residues (V335, K339, and I353) which are important for SRC-1 binding did not affect binding of Hr. This suggests that although Hr and SRC share similar recognition helices, they do not compete for the same molecular determinants at the surface of the RORα LBD. We next used a putative dominant negative Hr construct containing only the RID and cotransfected it with both wild-type Hr and RORα. HrRID did not affect RORα transcriptional activity but did hinder Hr repression. This demonstrates that HrRID indeed acts as a dominant negative for Hr action, and importantly, it does not displace endogenous coactivators.

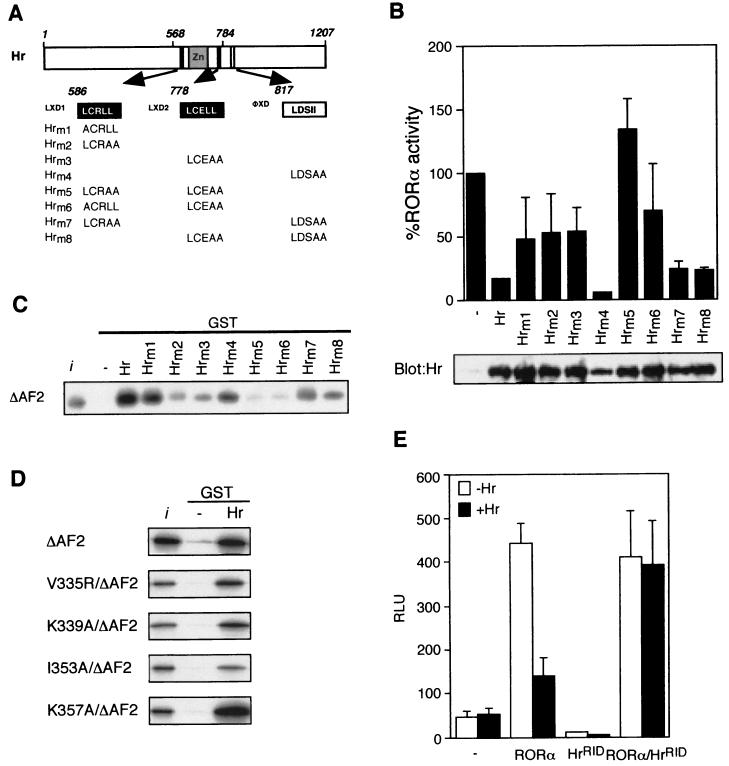

Specificity of Hr nuclear receptor targets is conferred by the AF-2 helix.

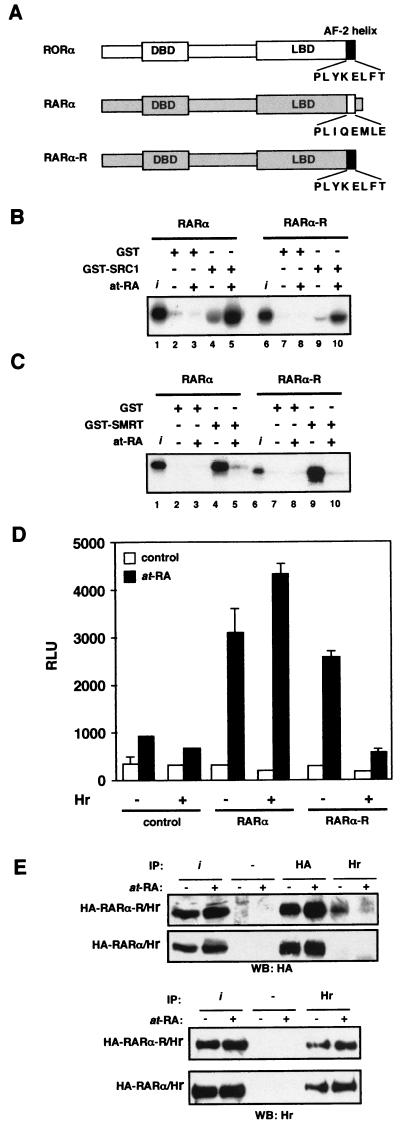

RORα is closely related to RARα, yet Hr does not bind RARα (42, 53). Given that coactivator-type binding motifs mediate RORα binding, we hypothesized that the specificity of Hr for RORα is conferred by the AF-2 helix. Previous observations that the C-terminal domain of RORβ is functional in the context of the RARα LBD (17) suggested that a RARα/RORα chimera could constitute a useful tool to test this idea. Thus, to determine if Hr binding could be transferred to a heterologous receptor, we generated a RARα mutant receptor in which the primary amino acid sequence of the AF-2 helix was changed to that of RORα, a change of only 5 amino acids (RARα-R) (Fig. 5A). We first tested whether the RARα-R chimeric protein retained the transcriptional properties of wild-type RARα. Using an in vitro GST pull-down assay, we showed that the RARα-R chimera is able to bind SRC-1 in a ligand-dependent fashion as well as its wild-type RARα counterpart (Fig. 5B). Similarly, the RARα-R chimera interacts with SMRT in the absence of retinoic acid and this interaction is abolished by the addition of ligand (Fig. 5C). These observations not only demonstrate that the RARα-R mutant is functional but, perhaps more importantly, that the AF-2 helix of RORα functions properly in the context of a liganded receptor, adding support to the hypothesis that RORα activity is indeed regulated by an endogenous ligand. Next, we tested the chimeric receptor for transcriptional activity. As expected, RARα activated gene transcription in response to at-RA in a transient-transfection assay (Fig. 5C). This response was not affected by the presence of Hr. Strikingly, RARα-R showed retinoic acid-dependent transcriptional activity, and cotransfection of Hr dramatically decreased the transcriptional activity of RARα-R. Finally, we show that the observed repression of the modified RARα-R is due to recruitment of Hr. As shown in Fig. 5E, the complex immunoprecipitated with the Hr antibody contains RARα-R but not wild-type RARα. The specificity of interaction between Hr and RARα-R is further highlighted by the observation of a slight decrease in interaction between these two proteins in the presence of retinoic acid, possibly reflecting a competition between Hr and coactivator complexes. These results clearly demonstrate that the specificity of Hr interaction with nuclear receptors resides within the AF-2 helix. Furthermore, these data also show that unlike other corepressors whose interaction with nuclear receptors is disrupted upon ligand binding (4, 22), Hr repression of RARα-R activity occurs in the presence of ligand. These results suggest that Hr function is unhindered by the presence of ligand in the context of the AF-2 helix of RORα, and thus Hr constitutes a distinct type of nuclear receptor corepressor.

FIG.5.

RORα AF-2 helix dictates specificity of Hr repression function. (A) Schematic representation of RORα and RARα, whose AF-2 helix is represented by a solid and an open box, respectively. RARα-R is a chimeric RARα encoding the RORα AF-2 helix. For GST pull-down assays, 35S-labeled RARα and RARα-R were incubated with GST, GST-SRC1RID (B), or GST-SMRTRID (C) in the absence (ethanol) or the presence of 10−6M at-RA. Input (i) represents 10% of the labeled protein used in a binding reaction. (D) Cos-1 cells were cotransfected with TREp3-TkLuc, pCMX (control), hRARα/hRXRα (RARα), or hRARα-R/hRXRα (RARα-R) in the absence (−) or the presence (+) of Hr. Cells were treated with ethanol (open bars) or with 10−8 M at-RA (closed bars). Normalized values are expressed in relative luciferase units (RLU). Error bars represent the standard deviation between duplicate samples. This is a representative experiment of a total of three independent experiments. (E) Hr interacts with RARα-R. Cos-1 cells were transiently transfected with pRK5-myc-rhr, pCMX-HA-RARα-R, or pCMX-HA-RARα. Cells were treated with ethanol (−) or 10−8 M at-RA (+). Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with HA antibody, Hr antibody, or rabbit immunoglobulin G (as negative control), followed by immunoblotting with anti-HA or anti-Hr. The input lanes (i) represents 40% of lysate used in each IP.

DISCUSSION

Nuclear receptors are transcriptional regulators capable of both activating and repressing specific gene networks in response to developmental and physiological cues. The choice between activation and repression is thought to depend on specific, mutually exclusive interactions with coactivators and corepressors. These interactions take place through common surface determinants in the receptor LBD and are tightly regulated by ligand binding (reviewed in reference 16). This proposed mode of action constitutes an elegant and simple molecular mechanism through which a family of ligand-dependent transcription factors can efficiently and precisely control the expression of target genes.

The existence of constitutively active orphan nuclear receptors whose activity might be continuously stimulated by the presence of ubiquitous ligands (reviewed in reference 14) suggests that this class of nuclear receptors may utilize related but distinct molecular mechanisms to regulate their transcriptional functions. Here, we describe the functional interaction between RORα, a constitutively active orphan nuclear receptor, with a novel corepressor, the Hr protein. This study shows a novel function for Hr as a potent ligand-oblivious nuclear receptor corepressor. Strikingly, these results demonstrate that the targets of nuclear receptor corepressors can be specified by determinants encoded within the AF-2 helix.

Hr is a bifunctional corepressor.

Despite its lack of sequence identity with previously described corepressors such as SMRT and N-CoR, Hr has been shown to function as a nuclear receptor corepressor (42, 53). Hr interacts directly and specifically with T3R and can mediate transcriptional repression of unliganded T3R. Interaction with T3R is mediated by two ΦXXΦΦ-containing domains, and Hr likely mediates transcriptional repression through associated histone deacetylase activity (42). These data suggest that in the context of T3R, Hr functions in a manner similar to SMRT and N-CoR.

The finding that Hr, the same protein that can mediate ligand-independent repression by T3R, can also influence the activity of a constitutively active orphan receptor indicates that Hr can serve multiple roles in mediating transcriptional repression. Evidence that RORα may bind to an as-yet-unknown ligand suggests that Hr interacts with ligand-bound RORα, exactly the opposite of its mechanism of action on T3R. This assumption is clearly validated by the observation that Hr represses transcriptional activation by the retinoic acid-activated chimeric RARα-R protein (Fig. 5). Thus, Hr is a bifunctional corepressor, which can interact with different classes of nuclear receptors through distinct, well-conserved interaction domains: with T3R through ΦXXΦΦ motifs (42) and with RORα via two LXXLL motifs (Fig. 4).

The interaction of Hr with RORα through coactivator type binding motifs suggests that Hr might compete for coactivator binding. However, our results show that Hr interaction with RORα does not require the same molecular determinants on the surface of the LBD. In addition, expression of the minimal region of Hr shown to bind RORα does not hinder transcriptional activation as would be expected if Hr interaction displaced coactivator binding. Thus, repression of ligand bound RORα by Hr is not due to mere competition or occlusion of the coactivator binding site, but instead likely occurs through one or more of the independent repression domains previously defined in Hr (42).

The AF-2 helix dictates corepressor binding specificity.

Biochemical and X-ray crystallographic studies have shown that the AF-2 helix plays a crucial role in controlling the assembly of nuclear receptors and coactivator proteins (9, 39, 46, 57). The AF-2 helix participates in the formation of a charged clamp defined by highly conserved residues among nuclear receptors, suggesting a shared structural role for the AF-2 helix in the common mechanism for coactivator binding with nuclear receptors. This study reveals for the first time that the AF-2 helix can also mediate binding between a corepressor and a nuclear receptor. Indeed, introduction of the AF-2 helix sequence of RORα within the otherwise-intact RARα, a change of only 5 amino acids, allowed Hr to repress the transcriptional activity of the mutant RARα (Fig. 5). Thus, the primary amino acid sequence of the AF-2 helix can dictate binding specificity between a corepressor and a nuclear receptor. This observation implies that nuclear receptor AF-2 helices, although highly conserved, encode unique determinants that dictate coregulator interactions. This mechanism parallels the code embedded within the LXXLL and ΦXXΦΦ motifs that confers interaction specificity to coactivators and corepressors (3, 9, 23, 36, 38, 40, 41, 45).

We have shown that in vitro, the RORα LBD is in an active conformation, favoring coactivator interaction and exerting an inhibitory influence on Hr binding. This implies that the AF-2 helix masks the molecular determinants required for Hr binding, which may be otherwise unveiled in the presence of the corepressor under the appropriate conditions. For example, a tertiary protein may be necessary to anchor the AF-2 helix away from the surface of the LBD and allow Hr binding. Alternatively, phosphorylation may also be an important component influencing the dynamics of the AF-2 helix and enhancing Hr binding, thus shifting RORα into a repressed state. It has previously been shown that the affinity of peptides encoding LXXLL motifs for RORα is increased in the presence of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV (27).

Convergence of ROR and Hr function in vivo.

The functional significance of the interaction between Hr and RORα described in this study is clearly demonstrated by the degree to which Hr can repress RORα-mediated transcriptional activation and is likely to be of biological importance. Mutations in the gene encoding RORα result in the staggerer phenotype, which is characterized by severe ataxia and defects in both Purkinje and granule cells (10, 18, 35, 50), suggesting that RORα is necessary for Purkinje cell survival. Interestingly, although hr is abundantly expressed in cerebellar granule cells, it is not present in Purkinje cells (52). This predicts that in Purkinje cells in which RORα activity is essential for survival, the receptor can function optimally. Given the developmental and tissue-specific expression of Hr (1, 52) and members of the ROR family (14), Hr likely acts as a developmental and tissue-specific inhibitor of ROR family members in which the level of Hr expression regulates the amount of ROR activity. More importantly, the expression of Hr is hormonally regulated (52), providing a means to control RORα activity in response to exogenous stimuli. Notably, T3 also influences cerebellar development, predicting the convergence of ROR and thyroid hormone signaling pathways during the development of the cerebellum (18). These results provide the first direct evidence linking T3-dependent and ROR-dependent developmental processes.

Conclusion.

The identification of Hr as a potent repressor of RORα transcriptional activity and the investigation into the molecular mechanisms regulating the interaction between the two proteins have revealed significant new insights into how RORα regulates gene expression. We have shown that RORα constitutive activity is likely dependent on the presence of an endogenous ligand and that a new class of nuclear receptor corepressors, represented here by Hr, can modulate that activity. More importantly, we have demonstrated that the interaction between Hr and nuclear receptors also requires specific determinants encoded within the AF-2 helix, a surprising finding in view of the results of previous studies attributing an inhibitory role to the AF-2 helix in nuclear receptor-coregulator interactions. Finally, the observation that Hr inhibits the transcriptional activity of a liganded receptor (RARα-R) suggests that this repression mechanism is likely to be shared by other members of the nuclear receptor family. The mechanism is also likely to be of physiological importance, as transcriptional repression in the absence or presence of ligand constitutes an essential molecular pathway through which nuclear receptors control development and homeostasis (24, 26, 29).

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Klingenstein Fund. A. N. Moraitis is the recipient of a training grant from the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec. V. Giguère holds a CIHR senior scientist career award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad, W., M. Faiyaz ul Haque, V. Brancolini, H. C. Tsou, S. ul Haque, H. Lam, V. M. Aita, J. Owen, M. deBlaquiere, J. Frank, P. B. Cserhalmi-Friedman, A. Leask, J. A. McGrath, M. Peacocke, M. Ahmad, J. Ott, and A. M. Christiano. 1998. Alopecia universalis associated with a mutation in the human hairless gene. Science 279:720-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkins, G. B., X. Hu, M. G. Guenther, C. Rachez, L. P. Freedman, and M. A. Lazar. 1999. Coactivators for the orphan nuclear receptor RORα. Mol. Endocrinol. 13:1550-1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang, C.-Y., J. D. Norris, H. Grøn, L. A. Paige, P. T. Hamilton, D. J. Kenan, D. Fowlkes, and D. P. McDonnell. 1999. Dissection of the LXXLL nuclear receptor-coactivator interaction motif using combinatorial peptide libraries: discovery of peptide antagonists of estrogen receptors α and β. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:8226-8239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, J. D., and R. M. Evans. 1995. A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature 377:454-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chomez, P., I. Neveu, A. Mansen, E. Kiesler, L. Larsson, B. Vennstrom, and E. Arenas. 2000. Increased cell death and delayed development in the cerebellum of mice lacking the rev-erbA(α) orphan receptor. Development 127:1489-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cichon, S., M. Anker, I. R. Vogt, H. Rohleder, M. Putzstuck, A. Hillmer, S. A. Farooq, K. S. Al-Dhafri, M. Ahmad, S. Haque, M. Rietschel, P. Propping, R. Kruse, and M. M. Nothen. 1998. Cloning, genomic organization, alternative transcripts and mutational analysis of the gene responsible for autosomal recessive universal congenital alopecia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 7:1671-1679. (Erratum, 7: 1987-1988.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crawford, P. A., C. Dorh, Y. Sadovsky, and J. Milbrandt. 1998. Nuclear receptor DAX-1 recruits nuclear receptor corepressor N-CoR to steroidogenic factor 1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:2949-2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danielian, P. S., R. White, J. A. Lees, and M. G. Parker. 1992. Identification of a conserved region required for hormone dependent transcriptional activation by steroid hormone receptors. EMBO J. 11:1025-1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darimont, B. D., R. L. Wagner, J. W. Apriletti, M. R. Stallcup, P. J. Kushner, J. D. Baxter, R. J. Fletterick, and K. R. Yamamoto. 1998. Structure and specificity of nuclear receptor-coactivator interactions. Genes Dev. 12:3343-3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dussault, I., D. Fawcett, A. Matthyssen, J.-A. Bader, and V. Giguère. 1998. Orphan nuclear receptor RORα-deficient mice display the cerebellar defects of staggerer. Mech. Dev. 70:147-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dussault, I., and V. Giguère. 1997. Differential regulation of the N-myc proto-oncogene by RORα and RVR, two orphan members of the superfamily of nuclear hormone receptors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:1860-1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng, W., R. C. J. Ribeiro, R. L. Wagner, H. Nguyen, J. W. Apriletti, R. J. Fletterick, J. D. Baxter, P. J. Kushner, and B. L. West. 1998. Hormone-dependent coactivator binding to a hydrophobic cleft on nuclear receptors. Science 280:1747-1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forman, B., J. Chen, B. Blumberg, S. A. Kliewer, R. Henshaw, E. S. Ong, and R. M. Evans. 1994. Cross-talk among RORα1 and the Rev-erb family of orphan nuclear receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 8:1253-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giguère, V. 1999. Orphan nuclear receptors: from gene to function. Endocr. Rev. 20:689-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giguère, V., M. Tini, G. Flock, E. S. Ong, R. M. Evans, and G. Otulakowski. 1994. Isoform-specific amino-terminal domains dictate DNA-binding properties of RORα, a novel family of orphan nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. 8:538-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glass, C. K., and M. G. Rosenfeld. 2000. The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. 14:121-141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greiner, E. F., J. Kirfel, H. Greschik, U. Dörflinger, P. Becker, A. Mercep, and R. Schüle. 1996. Functional analysis of retinoid Z receptor β, a brain-specific nuclear orphan receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:10105-10110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton, B. A., W. N. Frankel, A. W. Kerrebrock, T. L. Hawkins, W. FitzHugh, K. Kusumi, L. B. Russell, K. L. Mueller, V. van Berkel, B. W. Birren, L. Kruglyak, and E. S. Lander. 1996. Disruption of nuclear hormone receptor RORα in staggerer mice. Nature 379:736-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harding, H. P., G. B. Atkins, A. B. Jaffe, W. J. Seo, and M. A. Lazar. 1997. Transcriptional activation and repression by RORα, an orphan nuclear receptor required for cerebellar development. Mol. Endocrinol. 11:1737-1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heery, D. M., E. Kalkhoven, S. Hoare, and M. G. Parker. 1997. A signature motif in transcriptional co-activators mediates binding to nuclear receptors. Nature 387:733-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollenberg, S. M., R. Sternglanz, P. F. Cheng, and H. Weintraub. 1995. Identification of a new family of tissue-specific basic helix-loop-helix proteins with a two-hybrid system. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:3813-3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horlein, A. J., A. M. Naar, T. Heinzel, J. Torchia, B. Gloss, R. Kurokawa, A. Ryan, Y. Kamel, M. Soderstrom, C. K. Glass, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 1995. Ligand-independent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor co-repressor. Nature 377:397-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu, X., and M. A. Lazar. 1999. The CoRNR motif controls the recruitment of corepressors by nuclear hormone receptors. Nature 402:93-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu, X., and M. A. Lazar. 2000. Transcriptional repression by nuclear hormone receptors. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 11:6-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson, T. A., J. K. Richer, D. L. Bain, G. S. Takimoto, L. Tung, and K. B. Horwitz. 1997. The partial agonist activity of antagonist-occupied steroid receptors is controlled by a novel hinge domain-binding coactivator L7/Spa and the corepressors N-Cor or SMRT. Mol. Endocrinol. 11:693-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jepsen, K., O. Hermanson, T. M. Onami, A. S. Gleiberman, V. Lunyak, R. J. McEvilly, R. Kurokawa, V. Kumar, F. Liu, E. Seto, S. M. Hedrick, G. Mandel, C. K. Glass, D. W. Rose, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 2000. Combinatorial roles of the nuclear receptor corepressor in transcription and development. Cell 102:753-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kane, C. D., and A. R. Means. 2000. Activation of orphan receptor-mediated transcription by Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV. EMBO J. 19:691-701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koibuchi, N., and W. W. Chin. 2000. Thyroid hormone action and brain development. Trends Endo. Metab. 11:123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koide, T., M. Downes, R. A. Chandraratna, B. Blumberg, and K. Umesono. 2001. Active repression of RAR signaling is required for head formation. Genes Dev. 15:2111-2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurokawa, R., M. Soderstrom, A. Horlein, S. Halachmi, M. Brown, M. G. Rosenfeld, and C. K. Glass. 1995. Polarity-specific activities of retinoic acid receptors determined by a co-repressor. Nature 377:451-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lavinsky, R. M., K. Jepsen, T. Heinzel, J. Torchia, T. M. Mullen, R. Schiff, A. L. Del-Rio, M. Ricote, S. Ngo, J. Gemsch, S. G. Hilsenbeck, C. K. Osborne, C. K. Glass, M. G. Rosenfeld, and D. W. Rose. 1998. Diverse signaling pathways modulate nuclear receptor recruitment of N-CoR and SMRT complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:2920-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee, J. W., F. Ryan, J. C. Swaffield, S. A. Johnston, and D. D. Moore. 1995. Interaction of thyroid-hormone receptor with a conserved transcriptional mediator. Nature 374:91-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mak, H. Y., S. Hoare, P. M. Henttu, and M. G. Parker. 1999. Molecular determinants of the estrogen receptor-coactivator interface. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:3895-3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mangelsdorf, D. J., C. Thummel, M. Beato, P. Herrlich, G. Schütz, K. Umesono, B. Blumberg, P. Kastner, M. Mark, P. Chambon, and R. M. Evans. 1995. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell 83:835-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matysiak-Scholze, U., and M. Nehls. 1997. The structural integrity of RORα isoforms is mutated in staggerer mice: cerebellar coexpression of RORα1 and RORα4. Genomics 43:78-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McInerney, E. M., D. W. Rose, S. E. Flynn, S. Westin, T. M. Mullen, A. Krones, J. Inostroza, J. Torchia, R. T. Nolte, N. Assa-Munt, M. V. Milburn, C. K. Glass, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 1998. Determinants of coactivator LXXLL motif specificity in nuclear receptor transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 12:3357-3368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKenna, N. J., R. B. Lanz, and B. W. O'Malley. 1999. Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocr. Rev. 20:321-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagy, L., H. Y. Kao, J. D. Love, C. Li, E. Banayo, J. T. Gooch, V. Krishna, K. Chatterjee, R. M. Evans, and J. W. Schwabe. 1999. Mechanism of corepressor binding and release from nuclear hormone receptors. Genes Dev. 13:3209-3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nolte, R. T., G. B. Wisely, S. Westin, J. E. Cobb, M. H. Lambert, R. Kurokawa, M. G. Rosenfeld, T. M. Willson, C. K. Glass, and M. V. Milburn. 1998. Ligand binding and co-activator assembly of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ. Nature 395:137-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Norris, J. D., L. A. Paige, D. J. Christensen, C. Y. Chang, M. R. Huacani, D. Fan, P. T. Hamilton, D. M. Fowlkes, and D. P. McDonnell. 1999. Peptide antagonists of the human estrogen receptor. Science 285:744-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perissi, V., L. M. Staszewski, E. M. McInerney, R. Kurokawa, A. Krones, D. W. Rose, M. H. Lambert, M. V. Milburn, C. K. Glass, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 1999. Molecular determinants of nuclear receptor-corepressor interaction. Genes Dev. 13:3198-3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Potter, G. B., G. M. J. Beaudoin, I. I. I., C. L. DeRenzo, J. M. Zarach, S. H. Chen, and C. C. Thompson. 2001. The hairless gene mutated in congenital hair loss disorders encodes a novel nuclear receptor corepressor. Genes Dev. 15:2687-2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Retnakaran, R., G. Flock, and V. Giguère. 1994. Identification of RVR, a novel orphan nuclear receptor that acts as a negative transcriptional regulator. Mol. Endocrinol. 8:1234-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sande, S., and M. L. Privalsky. 1996. Identification of Tracs (T-3 receptor-associating cofactors), a family of cofactors that associate with, and modulate the activity of, nuclear hormone receptors. Mol. Endocrinol. 10:813-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sauvé, F., L. D. B. McBroom, J. Gallant, A. N. Moraitis, F. Labrie, and V. Giguère. 2001. CIA, a novel estrogen receptor coactivator with a bifunctional nuclear receptor interacting determinant. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:343-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shiau, A. K., D. Barstad, P. M. Loria, L. Cheng, P. J. Kushner, D. A. Agard, and G. L. Greene. 1998. The structural basis of estrogen receptor/coactivator recognition and the antagonism of this interaction by tamoxifen. Cell 95:927-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shibata, H., Z. Nawaz, S. Y. Tsai, B. W. O'Malley, and M. J. Tsai. 1997. Gene silencing by chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor I (COUP-TFI) is mediated by transcriptional corepressors, nuclear receptor-corepressor (N-Cor) and silencing mediator for retinoic Acid receptor and thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT). Mol. Endocrinol. 11:714-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith, C. L., Z. Nawaz, and B. W. O'Malley. 1997. Coactivator and corepressor regulation of the agonist/antagonist activity of the mixed antiestrogen, 4-hydroxytamoxifen. Mol. Endocrinol. 11:657-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stehlin, C., J. M. Wurtz, A. Steinmetz, E. Greiner, R. Schüle, D. Moras, and J. P. Renaud. 2001. X-ray structure of the orphan nuclear receptor RORβ ligand-binding domain in the active conformation. EMBO J. 20:5822-5831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steinmayr, M., E. André, F. Conquet, L. Rondi-Reig, N. Delhaye-Bouchaud, N. Auclair, H. Daniel, F. Crepel, J. Mariani, C. Sotelo, and M. Becker-André. 1998. staggerer phenotype in retinoid-related orphan receptor α-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3960-3965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoye, J. P., S. Fenner, G. E. Greenoak, C. Moran, and J. M. Coffin. 1988. Role of endogenous retroviruses as mutagens: the hairless mutation of mice. Cell 54:383-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thompson, C. C. 1996. Thyroid hormone-responsive genes in developing cerebellum include a novel synaptotagmin and a hairless homolog. J. Neurosci. 16:7832-7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thompson, C. C., and M. C. Bottcher. 1997. The product of a thyroid hormone-responsive gene interacts with thyroid hormone receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:8527-8532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thompson, C. C., and G. B. Potter. 2000. Thyroid hormone action in neural development. Cereb. Cortex 10:939-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tini, M., R. A. Fraser, and V. Giguère. 1995. Functional interactions between retinoic acid-related orphan nuclear receptor (RORα) and the retinoic acid receptors in the regulation of the γF-crystallin promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 270:20156-20161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Umesono, K., K. K. Murakami, C. C. Thompson, and R. M. Evans. 1991. Direct repeats as selective response elements for the thyroid hormone, retinoic acid, and vitamin D3 receptors. Cell 65:1255-1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Westin, S., R. Kurokawa, R. T. Nolte, G. B. Wisely, E. M. McInerney, D. W. Rose, M. V. Milburn, M. G. Rosenfeld, and C. K. Glass. 1998. Interactions controlling the assembly of nuclear-receptor heterodimers and co-activators. Nature 395:199-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wurtz, J. M., W. Bourguet, J. P. Renaud, V. Vivat, P. Chambon, D. Moras, and H. Gronemeyer. 1996. A canonical structure for the ligand-binding domain of nuclear receptors. Nature Struct. Biol. 3:87-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zamir, I., H. P. Harding, G. B. Atkins, A. Hörlein, C. K. Glass, M. G. Rosenfeld, and M. A. Lazar. 1996. A nuclear hormone receptor corepressor mediates transcriptional silencing by receptors with distinct repression domains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:5458-5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]