Abstract

In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the Cdc3p, Cdc10p, Cdc11p, Cdc12p, and Sep7p/Shs1p septins assemble early in the cell cycle in a ring that marks the future cytokinetic site. The septins appear to be major structural components of a set of filaments at the mother-bud neck and function as a scaffold for recruiting proteins involved in cytokinesis and other processes. We isolated a novel gene, BNI5, as a dosage suppressor of the cdc12-6 growth defect. Overexpression of BNI5 also suppressed the growth defects of cdc10-1, cdc11-6, and sep7Δ strains. Loss of BNI5 resulted in a cytokinesis defect, as evidenced by the formation of connected cells with shared cytoplasms, and deletion of BNI5 in a cdc3-6, cdc10-1, cdc11-6, cdc12-6, or sep7Δ mutant strain resulted in enhanced defects in septin localization and cytokinesis. Bni5p localizes to the mother-bud neck in a septin-dependent manner shortly after bud emergence and disappears from the neck approximately 2 to 3 min before spindle disassembly. Two-hybrid, in vitro binding, and protein-localization studies suggest that Bni5p interacts with the N-terminal domain of Cdc11p, which also appears to be sufficient for the localization of Cdc11p, its interaction with other septins, and other critical aspects of its function. Our data suggest that the Bni5p-septin interaction is important for septin ring stability and function, which is in turn critical for normal cytokinesis.

Cytokinesis in animal cells involves an actomyosin-based contractile ring, which forms late in the cell cycle and constricts the plasma membrane, resulting in the division of one cell into two cells. In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the cleavage plane is specified early in the cell cycle, and cytokinesis involves the concerted action of actomyosin ring contraction and septum formation (5, 37, 55). Despite some differences in the morphological features and timing of certain cytokinetic events between yeast and animal cells, many of the components involved are conserved (18). In addition to the conserved involvement of the actomyosin contractile ring, it is now widely appreciated that the septins also play a critical role in cytokinesis in both yeast and animal cells.

Septins are a family of proteins that were identified first in yeast and subsequently in various other fungi and animals (for review, see references 20, 32, and 39). Septin family members possess at least 26% amino acid sequence identity. All of the known septins possess an N-terminal P-loop and other sequences conserved in the GTPase superfamily of nucleotide-binding proteins (8). In addition, at or near their C termini, most septins possess a predicted coiled-coil domain (for review, see reference 39) that may be important in protein-protein interactions.

In yeast, the Cdc3p, Cdc10p, Cdc11p, Cdc12p, and Sep7p (or Shs1p) septins all localize to the presumptive bud site before bud emergence and remain at the mother-bud neck until after cytokinesis (11, 21, 28, 33, 45; M. S. Longtine, unpublished observations). Recent studies have indicated that the onset of contraction of the actomyosin ring results in division of the septins between the mother cell and the daughter cells (36, 38). Following cell separation, the septins disappear from the old cleavage site. At a restrictive temperature, temperature-sensitive mutations in CDC3, CDC10, CDC11, or CDC12 result in severe defects in cytokinesis and cell morphogenesis, yielding elongated, connected cells with multiple nuclei (1, 29), whereas loss of SEP7 function leads to milder bud elongation and cytokinetic defects (11, 45). Cdc3p, Cdc10p, Cdc11p, and Cdc12p copurify and form filaments in vitro (22), and they appear to be major structural components of the filaments observed at the neck by electron microscopy (9, 10, 22), although the details of protein arrangement in the filaments are not yet clear (22, 40).

The septins are thought to function as a scaffold for the localized assembly of various proteins at the mother-bud neck (20, 26, 40), including proteins important for cytokinesis. In a septin-dependent manner, the sole yeast type II myosin, Myo1p, assembles into a ring at the incipient budding site early in the cell cycle, whereas F actin is recruited to the myosin ring only late in the cell cycle, just before spindle disassembly and actomyosin ring contraction (5, 36, 37). Hof1p (or Cyk2p) also forms a septin-dependent ring at the mother-bud neck and appears to play an important role in modulating the stability of the actomyosin ring during contraction (36) and/or in septum formation (55). In addition to roles in cytokinesis, the yeast septins appear to be critical for diverse cellular functions, including the localization of chitin deposition (13), bud site selection (12), mother-daughter cell compartmentalization (3, 54), pheromone-induced morphogenesis (25), and the coordination of mitotic entry with morphogenesis (4, 11, 16, 42, 47).

To identify genes that are important for septin function, we sought high-copy suppressors of the cdc12-6 growth defect. We describe here the identification and analysis of a novel gene, BNI5. Our data suggest that Bni5p is important for providing stability to the neck-localized septins, probably through direct interactions with Cdc11p and perhaps also the other septins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain and plasmid construction.

The yeast strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. All strains constructed in this study were confirmed by PCR or Southern hybridization (data not shown). To visualize septin-ring or microtubule structures, a plasmid containing a CDC10 promoter-controlled yellow fluorescence protein gene (YFP)-CDC10 fusion (51) or a TUB1 promoter-controlled TUB1-green fluorescent protein gene (GFP) fusion (53) was integrated into the indicated strains at the LEU2 locus. Complete deletions of the BNI5 (bni5Δ::KanMX6), HOF1/CYK2 (hof1Δ::His3MX6), CDC10 (cdc10Δ::KanMX6), CDC11 (cdc11Δ::KanMX6), and SEP7/SHS1 (sep7Δ::His3MX6) open reading frames (ORFs) were generated by the one-step gene disruption method (41). A strain expressing a BNI5-GFP2 fusion protein under endogenous BNI5 promoter control (KLY1737) was generated by C-terminally tagging the chromosomal copy of BNI5 in KLY1546 with a GFP2::KanMX6 fragment obtained by PCR with pSK1558 (a derivative of pFA6a-KanMX6 [41] that contains one additional copy of GFPS65T between the PacI and BssHII sites) as a template. Strain KLY1737 did not exhibit any detectable defects (data not shown), suggesting that Bni5p-GFP2 is functional. Strain KLY1718 was generated by introducing a plasmid containing GAL1 promoter-controlled GST-CDC11 into strain KLY1546 before disrupting the CDC11 ORF as described above. This strain grew well in galactose medium, but poorly in glucose medium (data not shown). To carry out localization and functional analyses of various forms of Cdc11p, both wild-type and mutant CDC11 alleles were C-terminally tagged with a PCR fragment containing three hemagglutinin (HA) epitopes (HA3), cloned into the URA3-based integration vector pRS306 (48), and then integrated into KLY1718 at the URA3 locus by digesting the plasmids with Sse8387I. Strain KLY1718 integrated with pRS306 itself was used as a control. To determine the localization efficiency of YFP Bni5p or YFP-Cdc10p fusions in wild-type and cdc11 mutant backgrounds, plasmid pRS314 containing either ADH1 promoter-controlled YFP-BNI5 (pKL1900) or CDC10 promoter-controlled YFP-CDC10 (pKL1901) was transformed into the KLY1718-derived strains. After repressing expression of GAL1-GST-CDC11 by growth in glucose-containing medium for various lengths of time, the localizations of these proteins were examined. YFP-Bni5p is functional, because expression of ADH1-YFP-BNI5 suppressed the cdc11-6 or cdc12-6 growth defect (data not shown). To generate strain SKY1601, the CDC3 locus in strain KLY1546 was C-terminally tagged with a PCR fragment containing nine myc epitopes (myc9) bridged with a TEV protease (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.) cleavage site. Either full-length CDC11-HA3 or truncated cdc11-HA3 (amino acids 1 to 385) cloned in pRS306 was then integrated into SKY1601 at the URA3 locus (as described above) to generate strains SKY1824 and SKY1825, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1783a | MATaleu2-3,112 ura3-52 trp1-1 his4 can1r | 35 |

| M-1907b | MATa/α cdc12-6/cdc12-6 ura3-52/ura3-52 lys2-801/lys2-801 leu2-Δ1/leu2-Δ1 his3-Δ200/his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ63/trp1-Δ63 | This study |

| KLY1546c | MATahis3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3 | Laboratory stock |

| KLY1548c | MATα his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3 | Laboratory stock |

| KLY1415d | KLY1548 cdc3-6 | This study |

| KLY1798d | KLY1546 cdc10-1 | This study |

| KLY1419d | KLY1546 cdc11-6 | This study |

| KLY1422d | KLY1548 cdc12-6 | This study |

| KLY3937 | KLY1546 sep7Δ::His3MX6 | See text |

| KLY1350 | 1783 LEU2:YFP-CDC10 | See text |

| KLY1940 | 1783 bni5Δ::KanMX6 | See text |

| KLY1831 | 1783 bni5Δ::KanMX6 LEU2:YFP-CDC10 | See text |

| KLY2177 | KLY1548 cdc3-6 bni5Δ::KanMX6 | See text |

| KLY1803 | KLY1546 cdc10-1 bni5Δ::KanMX6 | See text |

| KLY2174 | KLY1546 cdc11-6 bni5Δ::KanMX6 | See text |

| KLY2010 | KLY1548 cdc12-6 bni5Δ::KanMX6 | See text |

| KLY3941 | KLY1546 sep7Δ::His3MX6 bni5Δ::KanMX6 | See text |

| KLY2214 | KLY1546 cdc12-6 LEU2:YFP-CDC10 | See text |

| KLY2216 | KLY1546 cdc12-6 bni5Δ::KanMX6 LEU2:YFP-CDC10 | See text |

| KLY3022 | 1783 hof1Δ::His3MX6 + pKL1754 | See text |

| SKY2115 | 1783 hof1Δ::His3MX6 bni5Δ::KanMX6 + pKL1754 | See text |

| KLY1737 | KLY1546 BNI5-GFP2::KanMX6 | See text |

| RLY292e | MATaura3-52 his3-Δ200 leu2-3,112 lys2-801 cyk2Δ::HIS3 | 36 |

| RLY332e | MATaura3-52 his3-Δ200 leu2-3,112 lys2-801 bar1Δ myo1Δ::HIS3 | 36 |

| KLY1715 | KLY1546 cdc10Δ::KanMX6 | See text |

| KLY1718 | KLY1546 cdc11Δ::KanMX6 + YCp111-GST/CDC11 | See text |

| KLY3404 | KLY1718 URA3:pRS306 + pKL1900 | See text |

| KLY3405 | KLY1718 URA3:CDC11-HA3 (1-415) + pKL1900 | See text |

| KLY3406 | KLY1718 URA3:cdc11-HA3 (1-385) + pKL1900 | See text |

| KLY3410 | KLY1718 URA3:cdc11-HA3 (31-385) + pKL1900 | See text |

| KLY3411 | KLY1718 URA3:cdc11-HA3 (1-200) + pKL1900 | See text |

| KLY3412 | KLY1718 URA3:pRS306 + pKL1901 | See text |

| KLY3413 | KLY1718 URA3:CDC11-HA3 (1-415) + pKL1901 | See text |

| KLY3414 | KLY1718 URA3:cdc11-HA3 (1-385) + pKL1901 | See text |

| KLY3418 | KLY1718 URA3:cdc11-HA3 (31-385) + pKL1901 | See text |

| KLY3419 | KLY1718 URA3:cdc11-HA3 (1-200) + pKL1901 | See text |

| SKY1601 | KLY1546 CDC3-TEV-myc9::KanMX6 | See text |

| SKY1824 | KLY1546 CDC3-TEV-myc9::KanMX6 URA3:CDC11-HA3 | See text |

| SKY1825 | KLY1546 CDC3-TEV-myc9::KanMX6 URA3:cdc11-HA3 (1-385) | See text |

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Name | Descriptiona | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pEG202-NLS | 2μ, HIS3, LexA DBD | Origene Technologies, Rockville, Md. |

| pGEX-KG | GST fusion expression vector | 27 |

| pJG4-5 | 2μ, TRP1, transcriptional AD | 2 |

| pRS314 | CEN TRP1 | 48 |

| pRS316 | CEN URA3 | 48 |

| YCplac33 | CEN URA3 | 24 |

| YCplac111 | CEN LEU2 | 24 |

| YEp351 | 2μ, LEU2 | 30 |

| YCp111-GST/ CDC11 | CEN LEU2 GAL1-GST-CDC11 | 22 |

| pKL899 | CEN LEU2 GAL1-BNI5 | See text |

| pKL1061 | YCplac111, CDC3 | See text |

| pKL1063 | YCplac111, CDC10 | See text |

| pKL1064 | YCplac111, CDC11 | See text |

| pKL1072 | YCplac111, CDC12 | See text |

| pKL2184 | YCplac33, SEP7/SHS1 | See text |

| pKL1119 | YEp351, BNI5 | See text |

| pKL1120 | YCplac111, BNI5 | See text |

| pKL1754 | pRS316, HOF1/CYK2-myc | See text |

| pKL1900 | pRS314, ADH-YFP-BNI5 | See text |

| pKL1901 | pRS314, YFP-CDC10 | See text |

| pKL1993 | GST-CDC11 | See text |

| pKL1995 | T7-BNI5-His6 | See text |

| pGEX-4T/CDC3 | GST-CDC3 | See text |

| pGEX-4T/CDC10 | GST-CDC10 | See text |

| pGEX-4T/CDC11 | GST-CDC11 | See text |

| pGEX-4T/CDC12 | GST-CDC12 | See text |

2μ indicates high-copy plasmids, and CEN indicates low-copy plasmids.

To construct plasmids for two-hybrid analyses, genes were amplified by PCR. For the tests of interaction between Bni5p and the septins (see Fig. 6), genomic DNA from strain S288C was used as template. Full-length BNI5 was fused to the VP16 transcriptional activation domain (AD) in pJG4-5 as an HA fusion protein (HA tag derived from the vector), whereas full-length CDC3, CDC10, CDC11, and CDC12 were cloned in-frame to the LexA DNA-binding domain (DBD) in pEG202-NLS (Origene Technologies, Rockville, Md.) (51). For the tests of interaction among the septins (see Table 5), the cloned genes were used as templates to amplify full-length or partial genes, and EcoRI or XhoI sites were included in the primers. The partial genes CDC3-N (amino acids 1 to 422), CDC3-C (amino acids 421 to 520), CDC11-N (amino acids 1 to 346), CDC11-C (amino acids 342 to 415), CDC12-N (amino acids 1 to 336), and CDC12-C (amino acids 325 to 407) were designed to include all but the predicted coiled-coil domains (the -N constructs) or only the predicted coiled-coil domains (the -C constructs), respectively. The amplified products were fused in frame to the DBD in pEG202 and to the AD in pJG4-5 by using the EcoRI site (CDC3), the XhoI site (CDC10, CDC11, CDC11-N, and CDC12), or the EcoRI-XhoI sites (all other constructs) of the vectors. The constructs cloned at the EcoRI or EcoRI-XhoI sites of pEG202 contain two additional amino acids (EF), and the constructs cloned at the XhoI site contain 13 additional amino acids (EFPGIRRPWRPLE) between the LexA DBD and the first amino acid of the fused protein. The full-length and -C constructs use the original stop codons of the fused genes; the -N constructs use a stop codon immediately downstream of the polylinker.

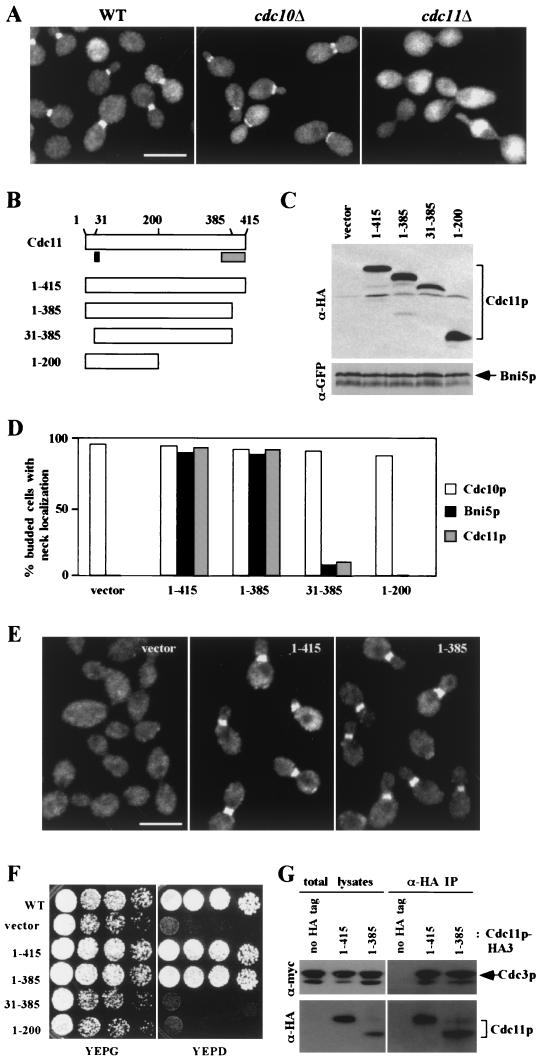

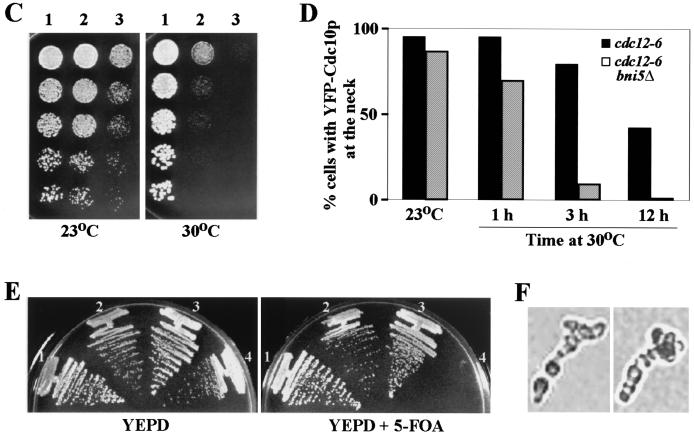

FIG. 6.

Dependence of Bni5p localization and Cdc11p function on the N-terminal portion of Cdc11p. (A) Localization of YFP-Bni5p in wild-type and viable septin deletion mutants. Wild-type strain KLY1546 and the cdc10Δ mutant (KLY1715), both expressing YFP-Bni5p from plasmid pKL1900, were cultured in YEP-glucose (YEPD) medium. Strain KLY1718 (cdc11Δ + YCp111-GST/CDC11) expressing YFP-Bni5p from plasmid pKL1900 was cultured in YEP-galactose overnight and then shifted to YEPD to repress GAL1-GST-CDC11 expression for 1 h prior to fixation. Bar, 5 μm. (B) Structures of the Cdc11p truncations used in these analyses (see Materials and Methods). Solid box, the conserved P-loop motif; shaded box, the predicted coiled-coil domain. (C to E) Strain KLY1718 (cdc11Δ + YCp111-GST/CDC11) derivatives harboring various C-terminally HA-tagged Cdc11p constructs and a plasmid expressing either YFP-CDC10 or ADH1-YFP-BNI5 were cultured in YEP-galactose (YEPG) overnight and then shifted to YEPD medium to repress GAL1-GST-CDC11 expression for 1 h. For each culture, total cellular lysates were prepared for Western analysis (C), and an aliquot was fixed with formaldehyde to assess Cdc10p and Bni5p localization by YFP fluorescence (D) or Cdc11p localization by immunostaining with an anti-HA antibody (D and E). Cdc10p, YFP-Cdc10p; Bni5p, YFP-Bni5p; Cdc11p, wild-type and mutant Cdc11p-HA proteins; vector, strain KLY3404 or KLY3412; 1-415, strain KLY3405 or KLY3413; 1-385, strain KLY3406 or KLY3414; 31-385, strain KLY3410 or KLY3418; 1-200, strain KLY3411 or KLY3419. For panel D, more than 200 cells with clear buds were counted for each sample. (F) Wild-type strain KLY1546 and the KLY1718 derivatives KLY3404, KLY3405, KLY3406, KLY3410, and KLY3411 were cultured overnight, serially diluted, and spotted onto either YEPG or YEPD plates at 30°C. Strains expressing either Cdc11p1-415 or Cdc11p1-385 grow better than the others even on YEPG, because GAL-GST-CDC11 does not fully complement the cdc11Δ mutation. (G) Strains expressing myc-tagged Cdc3p together with no tagged Cdc11p (SKY1601), HA-tagged full-length Cdc11p (SKY1824), or HA-tagged Cdc11p1-385 (SKY1825) were grown on YEPD at 30°C, and extracts were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Proteins present in the total lysates or in the immunoprecipitates (IP) prepared with anti-HA antibody were evaluated by Western blotting with anti-myc (above) and anti-HA (below) antibodies.

TABLE 5.

Two-hybrid interactions among the S. cerevisiae septinsa

| AD fusion | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) with DBD fusionb

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDC3 | CDC3-N | CDC3-C | CDC10 | CDC11 | CDC11-N | CDC11-C | CDC12 | CDC12-N | CDC12-C | |

| Nonec | 14 | 21 | 29 | 38 | 14 | 21 | 26 | 3 | 15 | 24 |

| CDC3 | 5 | 8 | 27 | 290 | 5 | 13 | 25 | 2,020 | 10 | 1,680 |

| CDC3-N | 1 | 7 | 29 | 150 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 6 |

| CDC3-C | 4 | 16 | 25 | 33 | 7 | 40 | 11 | 410 | 1 | 500 |

| CDC10 | 99 | 390 | 17 | 31 | 4 | 37 | 14 | 4 | 26 | 11 |

| CDC11 | 1,460 | 69 | 160 | 610 | 780 | 500 | 7 | 1,760 | 630 | 14 |

| CDC11-N | 350 | 7 | 24 | 250 | 66 | 1,640 | 8 | 1,760 | 570 | 19 |

| CDC11-C | 12 | 8 | 56 | 42 | 5 | 43 | 12 | 32 | 20 | 3 |

| CDC12 | 1,630 | 41 | 1,600 | 200 | 1,150 | 1,220 | 1 | 1,740 | 45 | 1,530 |

| CDC12-N | 260 | 270 | 39 | 51 | 920 | 1,610 | 27 | 190 | 13 | 19 |

| CDC12-C | 40 | 21 | 700 | 21 | 8 | 50 | 13 | 120 | 2 | 830 |

Two-hybrid assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

β-Galactosidase activities were measured on three independent isolates of each strain after growth for 16 h at 30°C in minimal medium containing 1% raffinose and 2% galactose. The average values (in Miller units) are shown. Values that are above 100 Miller units and at least sixfold higher than the corresponding control (pJG4-5 with no insert) are shown in boldface. -N and -C indicate the N- and C-terminal fragments, respectively, of the gene in question (see Materials and Methods for details).

None, pJG4-5 with no insert.

Other plasmids were constructed as follows. A SphI-SacI fragment containing full-length CDC3 or a SacI-XbaI fragment containing full-length CDC10, CDC11, or CDC12 was obtained by PCR and inserted into YCplac111 digested with the corresponding enzymes, creating plasmids pKL1061, pKL1063, pKL1064, and pKL1072, respectively. Similarly, a BamHI-SalI fragment containing full-length SEP7/SHS1 was inserted into YCplac33 digested with the corresponding enzymes, creating plasmid pKL2184. A PCR fragment containing full-length BNI5 was inserted into YEp351 at the SmaI site, creating plasmid pKL1119. pKL1120 was created by inserting a SacI-SphI fragment containing full-length BNI5 into YCplac111. To express BNI5 under GAL1 promoter control, a BspEI-StuI fragment containing the BNI5 ORF was cloned into vector pESC-LEU (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), creating plasmid pKL899. pKL1754 was created by inserting a PstI-BamHI fragment containing endogenous promoter-controlled HOF1/CYK2-myc (36) into the corresponding sites in pRS316. To construct plasmid pKL1995, which expresses full-length Bni5p fused to both N-terminal T7 and C-terminal six-His (His6) epitope tags, a BspEI-XhoI fragment comprising the entire BNI5 ORF was ligated into pET21b (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) after digestion with EcoRI and XhoI. The BspEI and EcoRI ends were end filled to allow blunt-end ligation. To construct plasmid pKL1993, which expresses full-length Cdc11p fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST), a BspEI (end filled)/SacI fragment containing full-length CDC11 was cloned into pGEX-KG (27) digested with BglII (end filled) and SacI. pGEX-4T/CDC3 was generated by inserting an EcoRI fragment from pEG202/CDC3 (14) into the EcoRI site of pGEX-4T (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.). pGEX-4T/CDC10, pGEX-4T/CDC11, and pGEX-4T/CDC12 were generated by inserting XhoI fragments from pEG202/CDC10, pEG202/CDC11, and pEG202/CDC12 (14), respectively, into the XhoI site of pGEX-4T.

Growth conditions and media.

Yeast cell culture and transformations were carried out by standard methods (46). Yeast extract-peptone (YEP)-glucose, YEP-galactose, and synthetic media were used as appropriate. For cell cycle synchronization, MATa cells were arrested with 5 μg of α mating pheromone (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml for 3 h at 30°C and then released into fresh growth medium. To select against cells containing URA3 plasmids, cells were streaked onto synthetic minimal medium (SDM) supplemented with 1 g of 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) per liter (6).

Two-hybrid assays.

Quantitative β-galactosidase assays were performed essentially as described previously (2) with reporter plasmid pSH18-34. The assays shown in Fig. 6 used diploid strains obtained by mating isolates of strains EGY48 and EGY194 that had been individually transformed with a pEG202-NLS-based plasmid or with a pJG4-5-based plasmid (as described above); the assays shown in Table 5 used isolates of strain EGY48 that had been cotransformed with a pEG202-based plasmid and with a pJG4-5-based plasmid.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

Cell lysates were prepared in TED buffer, composed of 40 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 0.25 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM AEBSF [4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride] (Pefabloc; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.), 10 μg of pepstatin A per ml (Sigma), 10 μg of leupeptin per ml (Sigma), and 10 μg of aprotinin per ml (Sigma), with an equal volume of glass beads (Sigma) as described previously (50). Immunoprecipitation was carried out as described previously (51). Proteins were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (2). Western blot analyses of total lysates were carried out with anti-GFP (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.), anti-HA.11 (Babco, Richmond, Calif.), anti-LexA (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, Calif.), anti-T7 (Novagen), anti-GST (Clontech), anti-myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), anti-Cdc28 (a gift of R. Deshaies, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, Calif.), and anti-Clb2 (a gift of D. Morgan, University of California, San Francisco, Calif.) antibodies as described previously (51), using the ECL enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

Preparation of recombinant proteins and in vitro protein-protein interaction studies.

Recombinant T7-Bni5p-His6, GST, GST-Cdc3p, GST-Cdc10p, GST-Cdc11p, and GST-Cdc12p fusion proteins were expressed from plasmids pKL1995, pGEX-KG, pGEX-4T/CDC3, pGEX-4T/CDC10, pKL1993, pGEX-4T/CDC11, and pGEX-4T/CDC12 in Escherichia coli. T7-Bni5p-His6 was partially purified with the use of a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid column (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and GST or GST-septins were purified by using glutathione-Sepharose beads (Sigma). In addition, T7-Bni5p-His6 was synthesized in vitro by using the T7-coupled rabbit reticulocyte system (Promega, Madison, Wis.). To investigate the interaction between Bni5p and the septins, in vitro-translated, 35S-labeled T7-Bni5p-His6 was added to either bead-bound GST-septins or bead-bound GST as a control, and then the mixture was incubated in a binding buffer (1× phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.5% NP-40) for 1 h at 4°C. The resin was then washed five times with the binding buffer. Bound proteins were eluted by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and then analyzed by autoradiogram after SDS-PAGE. To further investigate the interaction between Bni5p and Cdc11p, T7-Bni5p-His6 partially purified from E. coli was added to either bead-bound GST-Cdc11p or bead-bound GST, and then the mixture was incubated in a binding buffer as described above. Bound Bni5p was separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by immunoblotting with anti-T7 (Novagen) or anti-GST (Clontech) antibodies.

Cell staining and immunofluorescence microscopy.

To visualize plasma membranes, cells were stained with DiI (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) as described previously (36). To determine whether septa were formed between the cell bodies, chitin was stained as described previously (36) with Calcofluor (Fluorescent Brightener 28; Sigma), and 100-nm-interval serial sections were obtained with either a Bio-Rad MRC 1024 confocal scan head mounted on a Nikon Optiphot microscope with a ×60 planapochromat lens or a Leica TCS spectrophotometer confocal microscope. Indirect immunofluorescence was performed as described previously (34). Briefly, cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde, and Cdc11p was visualized with an anti-Cdc11p antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) and a rhodamine-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibody. Localization of GFP- or YFP-fused proteins was examined after fixing cells as described above. Similar results were obtained with unfixed cells. DNA was stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

Time-lapse imaging.

Cells were grown overnight in selective medium and placed on agarose pads as described previously (56). Living cells were imaged at room temperature on an Eclipse E600 microscope with differential interference contrast (DIC) optics and a Nikon 100/1.40 oil immersion objective. Images of Bni5p-GFP and Tub1p-GFP were collected through a neutral density filter with a value of 8 every 1 min with 0.8 s of exposure to fluorescent light by using a cooled RTE/CCD 782Y Interline camera (Princeton Instruments, Trenton, N.J.). The shutter was controlled automatically with a D122 shutter driver (UniBlitz, Rochester, N.Y.) and WinView 1.6.2 software (Princeton Instruments).

RESULTS

Isolation of BNI5 as a dosage suppressor of a septin temperature-sensitive mutant.

To identify proteins that interact with the septins, we screened a yeast genomic high-copy plasmid library (13) for genes able to suppress the temperature-sensitive lethality of a cdc12-6 mutant (strain M-1907). Initial screening at 37°C yielded no suppressing plasmids that did not contain a septin gene. However, we had found previously that overexpression of the GIN4 gene restored viability to a septin temperature-sensitive strain at a semipermissive temperature but not at 37°C (40). Thus, we screened an additional ∼100,000 transformants of strain M-1907 for growth at 32°C, recovering 30 plasmids that permitted growth at 32°C but not at 37°C. Sequencing of the ends of the inserts in these plasmids identified seven different genomic regions. Three plasmids that showed very good suppression had a region of overlap spanning nucleotides 323823 to 321482 of chromosome XIV. This region contains a single complete ORF of 1,347 bp (YNL166C), suggesting that overexpression of YNL166C was responsible for the observed suppression. This evidence and other data discussed below led us to rename YNL166C as “BNI5” (for Bud Neck Involved 5).

Next, we asked if overexpression of BNI5 could suppress the temperature-sensitive growth defects of other septin mutants. Indeed, overexpression of BNI5 either from a high-copy plasmid or under control of the GAL1 promoter suppressed the cdc10-1, cdc11-6, and sep7Δ mutants, in addition to the cdc12-6 mutant (Fig. 1 and Table 3). In contrast, no suppression of a cdc3-6 mutant was detected at several temperatures examined (Table 3). It is noteworthy that overexpression of BNI5 resulted in better suppression of the septin mutants tested than did overexpression of GIN4 (M. Longtine, unpublished data), which was previously shown to have a positive role in septin organization (40). These data suggest that Bni5p has a positive role in septin function.

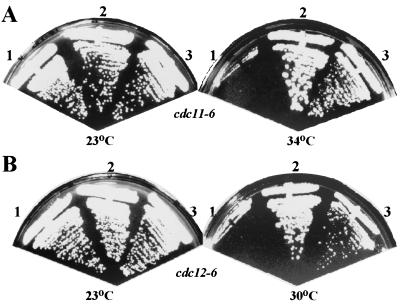

FIG. 1.

Suppression of the cdc11-6 and cdc12-6 growth defects by overexpression of BNI5. (A) Strain KLY1419 (cdc11-6) carrying a control vector (YCplac111) (no. 1), a low-copy-number CDC11 plasmid (pKL1064) (no. 2), or a multicopy BNI5 plasmid (pKL1119) (no. 3) was streaked onto YEP-glucose plates and grown at the indicated temperatures for 3 days. (B) Similar tests were performed with the cdc12-6 strain KLY1422 carrying plasmid YCplac111 (no. 1), pKL1072 (CDC12) (no. 2), or pKL1119 (BNI5) (no. 3).

TABLE 3.

Suppression of septin mutants by BNI5a

| Mutant | Plasmid type | Degree of suppression on growth medium

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| YEPD | YEPG | ||

| cdc3-6 | Vector | − | − |

| 2μ-BNI5 | − | − | |

| GAL1-BNI5 | − | − | |

| CDC3 | +4 | +4 | |

| cdc10-1 | Vector | − | − |

| 2μ-BNI5 | +1 | +1 | |

| GAL1-BNI5 | − | +1 | |

| CDC10 | +4 | +4 | |

| cdc11-6 | Vector | − | − |

| 2μ-BNI5 | +2 | +2 | |

| GAL1-BNI5 | − | +2 | |

| CDC11 | +4 | +4 | |

| cdc12-6 | Vector | − | − |

| 2μ-BNI5 | +2 | +2 | |

| GAL1-BNI5 | − | +2 | |

| CDC12 | +4 | +4 | |

| sep7Δ | Vector | − | − |

| 2μ-BNI5 | +1 | +1 | |

| GAL1-BNI5 | − | +1 | |

| SEP7 | +4 | +4 | |

The cdc3-6, cdc10-1, and cdc12-6 transformants were tested at 30°C, whereas the cdc11-6 and sep7Δ transformants were tested at 34 and 37°C, respectively. The cdc3-6 transformant was also tested at several other temperatures without detecting any suppression (data not shown). The degree of suppression of the growth defects is scored on an arbitrary scale from +1 to +4. −, no suppression. Strains: cdc3-6, KLY1415; cdc10-1, KLY1798; cdc11-6, KLY1419; cdc12-6, KLY1422; sep7Δ, KLY3937. Plasmids: 2μ-BNI5, pKL1119; GAL1-BNI5, pKL899; CDC3, pKL1061; CDC10, pKL1063; CDC11, pKL1064; CDC12, pKL1072; SEP7, pKL2184. Note that in this strain background, the sep7Δ mutation produces a significant growth defect with a chained-cell morphology at 37°C. The growth media used were YEP-glucose (YEPD) and YEP-galactose (YEPG).

BNI5 is predicted to encode a novel protein of 50 kDa that has no obvious homologues identified as yet in other organisms. In addition, Bni5p contains no currently recognizable functional motifs, except for three possible coiled-coil regions (for review, see reference 43) at amino acids 4 to 29, 161 to 183, and 363 to 383. Interestingly, both a Bni5p-GFP2 fusion protein expressed in S. cerevisiae (see Fig. 4C, below) and a T7-Bni5p-His6 fusion protein, either expressed in E. coli or translated in vitro in reticulocyte extracts (see Fig. 7B and C, below), migrated much more slowly than expected during SDS-PAGE (apparent molecular masses of 137 and 85 kDa, respectively, in contrast to the predicted masses of 102 and 52 kDa).

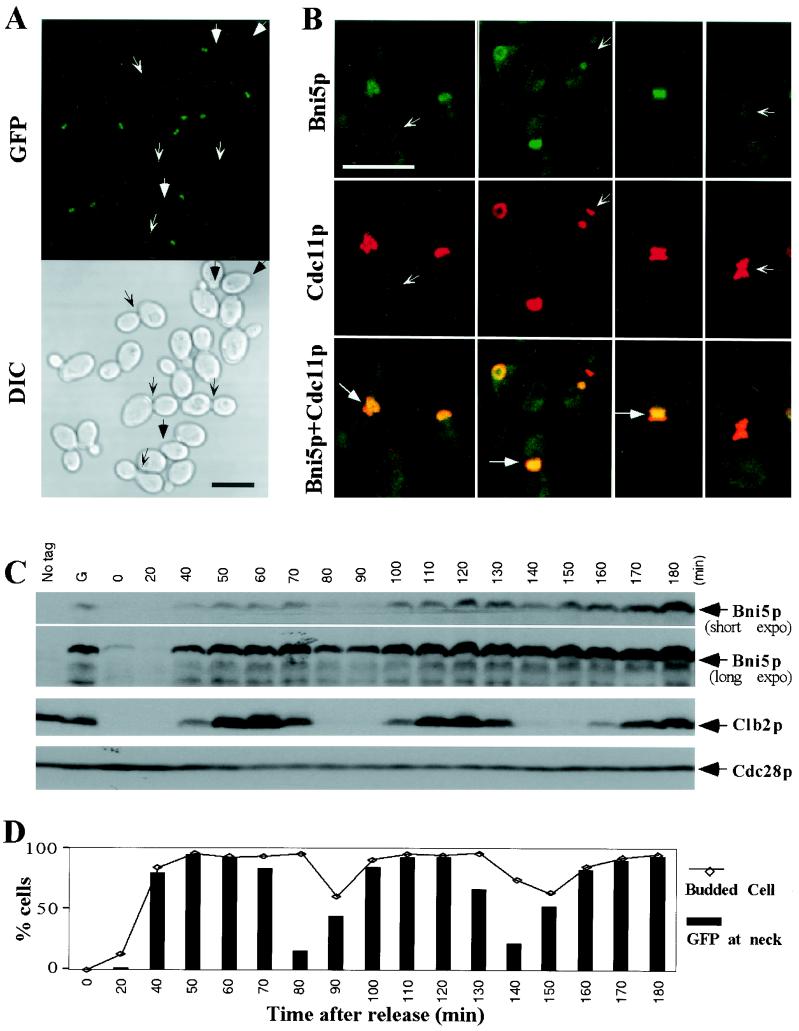

FIG. 4.

Expression and localization of Bni5p through the cell cycle. (A) Localization of Bni5p to the neck of budded cells. Exponentially growing cells of strain KLY1737 (BNI5-GFP2) were fixed and examined for Bni5p-GFP localization and cell morphology. Arrows, unbudded cells or cells with nascent buds without detectable Bni5p-GFP signal; barbed arrows, large-budded cells without detectable Bni5p-GFP signal. Bar, 5 μm. (B) Colocalization of Bni5p and Cdc11p. Bni5p was visualized by the GFP signal, whereas Cdc11p was detected by immunofluorescence. Barbed arrows, unbudded or large-budded cells with Cdc11p signal but no Bni5p signal; arrows, localization of Bni5p within the Cdc11p bands. Bar, 5 μm. (C and D) Levels of Bni5p and Bni5p localization in a synchronous culture. Strain KLY1737 was arrested in G1 by α-factor treatment for 3 h and then released. At the indicated times, samples were taken to prepare total cellular proteins and to determine Bni5p localization and the presence or absence of buds after fixation. (C) Proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against GFP, Clb2p, or Cdc28p. Both short and long exposures of the Bni5p-GFP immunoblot are shown for clarity. The Cdc28p levels provide a loading control. No tag, wild-type strain KLY1546; G, asynchronously growing KLY1737 cells. (D) The percentages of budded cells and of cells showing detectable Bni5p-GFP localization were determined by counting more than 200 cells for each time point.

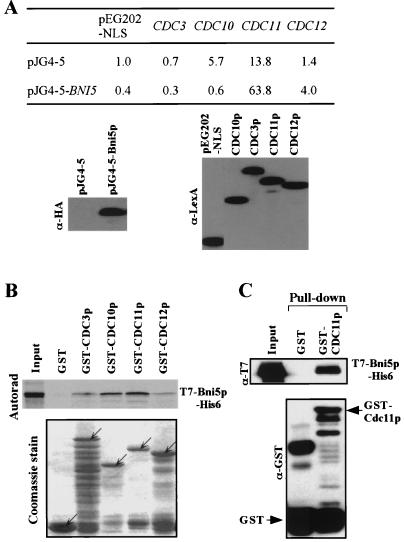

FIG. 7.

Physical interactions between Bni5p and septins. (A) Two-hybrid assays were conducted as described in Materials and Methods with plasmids that expressed the full-length genes as AD or DBD fusions. Numbers indicate the Miller units of β-galactosidase activity averaged from two independent experiments. Immunoblotting (lower panels) indicated that the four septin fusions were expressed equally. (B) In vitro binding studies were carried out with 35S-labeled, in vitro-translated T7-Bni5p-His6 and bacterially expressed, bead-bound GST and GST-septin fusion proteins (see Materials and Methods). After pull-down, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with Coomassie to detect GST and GST-septin fusion proteins (lower panel) and then subjected to autoradiography to detect bound Bni5p (upper panel). Note that although there was considerable degradation of the fusion proteins (particularly GST-Cdc3p), approximately equal amounts of the full-length fusion proteins were still present (arrows). Input, 2% of the 35S-labeled T7-Bni5p-His6 that was added to each binding reaction. (C) In vitro binding studies were carried out with bacterially expressed T7-Bni5p-His6 and bead-bound GST-Cdc11p or GST (see Materials and Methods). After SDS-PAGE, the amounts of bound T7-Bni5p-His6 were determined by immunoblotting with an anti-T7 antibody (upper panel), while the amounts of GST or GST-Cdc11p were determined by immunoblotting with an anti-GST antibody (lower panel). Input (upper panel), 5% of the T7-Bni5p-His6 that was incubated with GST or GST-Cdc11p.

Loss of BNI5 function results in a partially penetrant defect in cytokinesis.

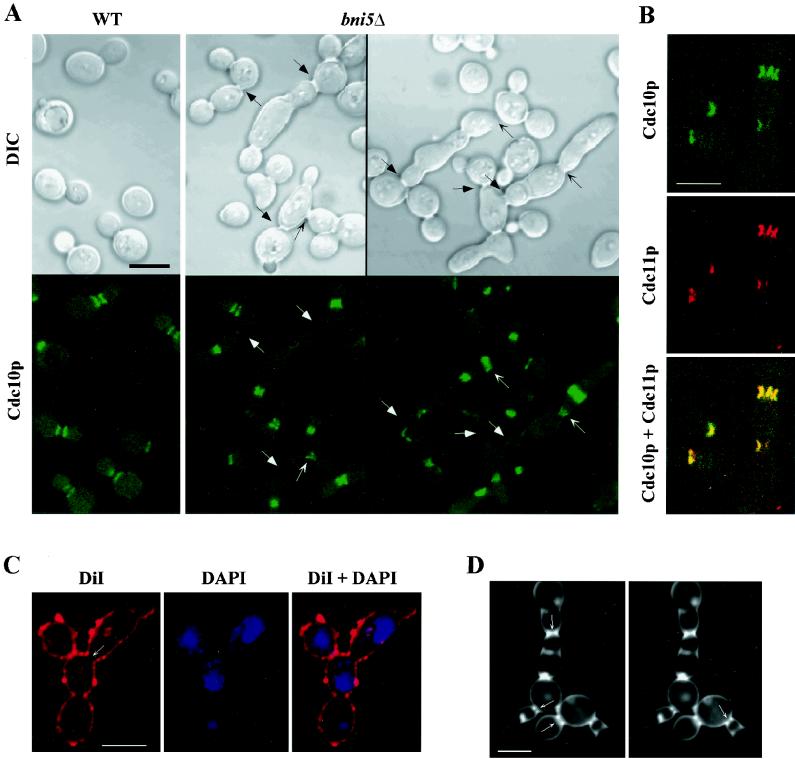

To investigate the function of Bni5p, we deleted BNI5 in a strain that expresses an integrated copy of YFP-CDC10 under control of the normal CDC10 promoter. The resulting strain (KLY1831) grew at normal rates at 23°C and had mild, but detectable, growth rate defects at 30 and 37°C (data not shown). After growth at 23°C, a small fraction of KLY1831 cells exhibited connected cells, occasionally with slightly elongated cell bodies. Following 12 h of growth at 37°C and sonication, ∼30% of KLY1831 cells were connected as short chains and/or displayed cell bodies that were more elongated than those of the wild type (Fig. 2A). In almost all cases, cells with normal morphology appeared also to have normal septin organization, as judged by the YFP-Cdc10p fluorescence signals. In contrast, most of the morphologically abnormal cells either lacked neck-localized YFP-Cdc10p (Fig. 2A, arrows) or displayed aberrantly organized YFP-Cdc10p structures (Fig. 2A, barbed arrows). In some cases, the aberrant septin structures appeared as a set of bars parallel to the mother-bud axis. Immunostaining with an anti-Cdc11p antibody revealed that the aberrant structures also contained Cdc11p (Fig. 2B) and thus, presumably, the other septins as well. Similar septin bars have been observed in cells carrying mutations in GIN4, CLA4, or NAP1, genes whose products appear to be involved in septin function and organization (40, 42).

FIG. 2.

Loss of BNI5 function leads to defects in septin localization and cytokinesis. (A) Strains KLY1350 (BNI5 YFP-CDC10) and KLY1831 (bni5Δ YFP-CDC10) grown in YEP-glucose at 23°C were shifted to 37°C for 12 h, fixed with formaldehyde, and examined by confocal microscopy. Representative morphologies are shown for each strain. Arrows indicate structures discussed in the text. WT, wild type. (B) Strain KLY1831 (bni5Δ YFP-CDC10), cultured as in panel A, was fixed with formaldehyde and subjected to immunostaining with anti-Cdc11p antibodies. (C) Strain KLY1940 (bni5Δ), cultured as in panel A, was fixed and stained with DiI to reveal membrane structures and stained with DAPI to visualize the DNA. The arrow indicates a neck with apparently connected cytoplasm. (D) Cells from the culture in panel C were stained with Calcofluor and subjected to confocal microscopy in 100-nm sections to investigate whether septa are formed. Arrows indicate seemingly incomplete primary septa as seen in the appropriate planes of focus. Bars, 5 μm.

To determine whether the connected cell morphology results from a defect in cytokinesis or in cell separation, bni5Δ cells were grown at 37°C, sonicated, and stained with DiI to reveal the plasma membrane. In this assay, approximately 50% (n = 90) of internal mother-bud necks of connected cells with three or more cell bodies appeared to have a shared cytoplasm (Fig. 2C). bni5Δ cells were also stained with Calcofluor to assay for primary septum formation in the internal necks of cells with three or more cell bodies. Serial optical sectioning with a confocal microscope revealed discontinuous chitin deposition in ∼90% of such necks (n = 110) (Fig. 2D), indicating defective primary septum formation. Together, these observations suggest that Bni5p plays a role in cytokinesis. Because the septins are essential for cytokinesis and septin structures are frequently abnormal in bni5Δ mutant cells, it is likely that the observed cytokinesis defects in bni5Δ strains are related to the abnormal septin organization.

Exacerbation by bni5Δ of septin and hof1 mutant defects.

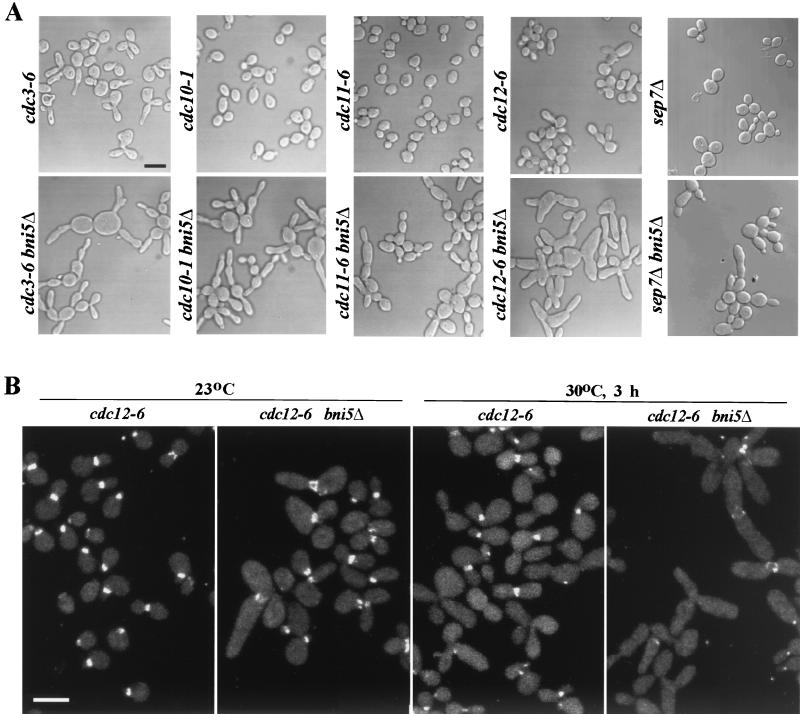

To further examine the interaction of Bni5p and the septins, a BNI5 deletion was introduced into cdc3-6, cdc10-1, cdc11-6, cdc12-6, and sep7Δ mutants. When cultured at temperatures that are normally semipermissive for these septin mutations, all double-mutant cells exhibited severely elongated buds and an apparent exacerbation of the cytokinesis defects (Fig. 3A). Compared to bni5Δ and septin single-mutant strains, bni5Δ cdc10-1, bni5Δ cdc11-6, bni5Δ cdc12-6, and bni5Δ sep7Δ double-mutant strains, but not a bni5Δ cdc3-6 double-mutant strain, also exhibited enhanced growth defects at elevated temperatures (Fig. 3C and data not shown). We also compared the localization of YFP-Cdc10p in cdc12-6 and bni5Δ cdc12-6 mutants. In the cdc12-6 strain, YFP-Cdc10p appeared to localize normally at 23°C, and approximately 80% of the cells possessed neck-localized YFP-Cdc10p after 3 h at 30°C (Fig. 3B and D). In contrast, in the bni5Δ cdc12-6 double-mutant strain, YFP-Cdc10p was often aberrantly localized at 23°C and was largely absent from the necks after 3 h at 30°C (Fig. 3B and D). Together, these observations suggest that Bni5p contributes to the maintenance or stability of neck-localized septins.

FIG. 3.

Synthetic effects in bni5Δ septin and bni5Δ hof1Δ double mutants. (A) Septin single-mutant and septin bni5Δ double-mutant strains were cultured overnight at 23°C and shifted to 30°C (or 37°C for sep7Δ and sep7Δ bni5Δ) for 3 h before fixation and examination by DIC microscopy. Strains: cdc3-6, KLY1415; cdc10-1, KLY1798; cdc11-6, KLY1419; cdc12-6, KLY1422; sep7Δ, KLY3937; cdc3-6 bni5Δ, KLY2177; cdc10-1 bni5Δ, KLY1803; cdc11-6 bni5Δ, KLY2174; cdc12-6 bni5Δ, KLY2010; sep7Δ bni5Δ, KLY3941. Bar, 5 μm. (B) Strains KLY2214 (cdc12-6 YFP-CDC10) and KLY2216 (cdc12-6 bni5Δ YFP-CDC10) were cultured overnight at 23°C and then shifted to 30°C. Samples were fixed for microscopic analyses during growth at 23°C and 3 h after the shift to 30°C. Bar, 5 μm. (C) Strains KLY1546 (wild type) (lane 1), KLY2214 (lane 2), and KLY2216 (lane 3) were cultured overnight. These cultures were serially diluted, spotted on YEP-glucose (YEPD), and incubated at the indicated temperature for 3 days. (D) Quantitation of cells with YFP-Cdc10p localization at the neck as a function of time. The strains used in panel B were cultured overnight at 23°C and then shifted to 30°C. Samples were fixed for microscopic analyses during growth at 23°C and at the indicated times after the shift to 30°C. The fractions of cells with YFP-Cdc10p localization at the neck were determined by counting more than 200 cells for each sample. Cells with partially localized YFP-Cdc10p at the neck were scored as positive. (E) Synthetic lethality between bni5Δ and hof1Δ. Strains 1783 (wild type) (no. 1), KLY1940 (bni5Δ) (no. 2), KLY3022 (hof1Δ with a HOF1/CYK2 plasmid) (no. 3), and SKY2115 (bni5Δ hof1Δ with the HOF1/CYK2 plasmid) (no. 4) were streaked on YEPD plates with or without 5-FOA to select against the URA3-based plasmid. (F) Two examples of bni5Δ hof1Δ double-mutant segregants after tetrad dissection of a heterozygous diploid.

We also tested for genetic interactions between Bni5p and other cellular components known to be important for cytokinesis. Loss of HOF1 function leads to a rapid disassembly of the actomyosin ring during its contraction, sometimes causing incomplete cytokinesis, whereas overexpression of HOF1 can block cytokinesis, probably by disrupting septin localization to the neck (31, 36, 55). Consistent with a role for Bni5p in cytokinesis, bni5Δ was synthetically lethal with a hof1Δ mutation (Fig. 3E). Tetrad analysis of a diploid strain heterozygous for the bni5Δ and hof1Δ mutations also showed that bni5Δ hof1Δ double-mutant spores were incapable of forming colonies at 23°C. Microscopic analysis of the double-mutant segregants (Fig. 3F) revealed that they produced several interconnected cell bodies before cessation of growth, which appeared to result from cell lysis. In contrast, a bni5Δ myo1Δ double-mutant strain did not exhibit any detectable synthetic defect (data not shown), suggesting that Bni5p and Myo1p may function in the same pathway.

Cell cycle-dependent expression and localization of Bni5p.

To investigate the localization of Bni5p, the chromosomal BNI5 gene was tagged at its C-terminal end with two tandem copies of GFP sequences. The tagged Bni5p appeared to be fully functional (see Materials and Methods). Microscopic observation of asynchronously growing cells revealed a band of Bni5p-GFP at the mother-bud neck in most budded cells (Fig. 4A). However, Bni5p was not detectably localized in most unbudded cells or in some cells with nascent buds, as well as in some large-budded cells (Fig. 4A). Immunostaining with an anti-Cdc11p antibody revealed that the Bni5p-GFP band corresponded approximately to that of the septins (Fig. 4B). Although the Bni5p band often appeared to occupy only a portion of the region defined by the septin staining (Fig. 4B, arrows), this appearance might just result from the greater strength of the Cdc11p signal relative to that of the Bni5p-GFP signal. Interestingly, Bni5p-GFP localization was not detected in some unbudded or nascent-budded cells, or in some large-budded cells, even when the septins were clearly present (Fig. 4B, barbed arrows). These data suggest that Bni5p arrives at the bud site approximately coincident with bud emergence (and thus ∼10 to 15 min later than the septins [21, 33]) and dissociates from the septin scaffold before cytokinesis.

To explore further the timing of Bni5p localization and to investigate whether the changes in localization reflect changes in Bni5p abundance, we examined Bni5p-GFP levels and localization in a synchronous culture. Bni5p-GFP levels were low in the α-factor-arrested cells and for 20 min after release (Fig. 4C). They then increased abruptly between 20 and 40 min and peaked at ∼50 to 70 min, approximately coincident with the G2/M peak in Clb2p levels (Fig. 4C). These observations are consistent with microarray data indicating that BNI5 mRNA is enriched in the S phase (52; Saccharomyces Genome Database, Stanford University, Calif.). The percentage of cells with detectably localized Bni5p-GFP also increased abruptly between 20 and 40 min after release and paralleled (but perhaps lagged slightly behind) the appearance of buds (Fig. 4D). Between 70 and 90 min after release, the number of cells with detectably localized Bni5p-GFP first fell abruptly, even though the number of budded cells remained high, and then began to increase again, presumably as new buds were formed in the next cell cycle (Fig. 4D). These data support the inferences about the timing of Bni5p localization and delocalization that were made from the observations on asynchronous cells, and they also suggest that the changes in Bni5p localization may reflect, at least in part, changes in Bni5p abundance during the cell cycle.

To further explore the timing of Bni5p delocalization from the neck, we made time-lapse observations of living cells expressing both Bni5p-GFP and Tub1p-GFP. As shown in Fig. 5, the band of Bni5p disappeared abruptly, without any detectable change in diameter, 2 to 4 min before spindle disassembly. Interestingly, Bni5p localization to the neck was still apparent in the cdc5-1 and cdc15-2 mutants, which are defective in exit from mitosis, after 3.5 h at a restrictive temperature (data not shown). Since the spindle disassembles at the onset of cytokinesis (36), these observations indicate that Bni5p delocalizes from the neck after mitotic exit has been triggered, but before the onset of cytokinesis.

FIG. 5.

Dynamics of Bni5p neck localization in relation to spindle structure. Strain KLY1737 (BNI5-GFP2) was transformed with TUB1-GFP (see Materials and Methods) and then examined by time-lapse video microscopy as described in Materials and Methods. In the two cells imaged here (outlined in the first panel), Bni5p-GFP is visible as a band crossing the elongated spindle. Spindle disassembly began at 10 min in the cell on the left or 12 min in the cell on the right.

Dependence of Bni5p localization on direct interaction with septins.

To ask if Bni5p neck localization depends on the septins, Bni5p with an N-terminal YFP tag was expressed under control of the ADH1 promoter in cdc3-6, cdc10-1, cdc11-6, and cdc12-6 strains. Although YFP-Bni5p was clearly localized to the neck in all four strains at permissive temperature, neck localization was lost when the cultures were shifted to a nonpermissive temperature for 30 (cdc10-1 and cdc12-6) or 60 (cdc3-6 and cdc11-6) min (Table 4 and data not shown). We also examined Bni5p localization in the viable septin deletion mutants. A cdc11Δ mutant conditionally expressing GAL-GST-CDC11 (KLY1718) was further transformed either with plasmid pKL1900 (expressing YFP-BNI5 under ADH1 promoter control) or with plasmid pKL1901 (expressing YFP-CDC10 under endogenous CDC10 promoter control), and the localization of YFP-Bni5p or YFP-Cdc10p was determined upon depletion of GST-Cdc11p by a shift to glucose-containing medium. The YFP-Bni5p rings completely disappeared from the bud necks within 1 h of the shift (Fig. 6A), whereas the YFP-Cdc10p signal was stable for at least several hours under the same conditions (data not shown). In contrast, YFP-Bni5p localized normally to the neck in cdc10Δ cells at 23°C (Fig. 6A), as well as in hof1Δ (strain RLY292) and myo1Δ (strain RLY332) cells (data not shown). In a sep7Δ mutant (strain KLY3937 containing plasmid pKL1900), the localization of YFP-Bni5p was severely impaired at temperatures from 23 to 37°C. However, at 23°C, approximately 10% of the population still exhibited normal-looking YFP-Bni5p rings (data not shown). Taken together, these observations suggest that Bni5p localization depends on the septins and perhaps particularly on Cdc11p. In addition, because the neck filaments are disorganized in a cdc10Δ background (22), these observations suggest that Bni5p, like Bud4p, Cdc3p, and Cdc11p (17, 22), does not depend on intact neck-filament structures for its normal localization.

TABLE 4.

Septin-dependent localization of Bni5pa

| Strain | % of budded cells with signalb

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 23°C | 37°C for 0.5 h | |

| Wild-type | ||

| YFP-Cdc10p | 89 | 91 |

| YFP-Bni5p | 76 | 79 |

| cdc12-6 | ||

| YFP-Cdc10p | 84 | 0 |

| YFP-Bni5p | 69 | 0 |

Wild-type strain KLY1546 or the isogenic cdc12-6 mutant KLY1422 was transformed either with pKL1901 (expressing YFP-CDC10 under endogenous CDC10 promoter control) or with pKL1900 (expressing YFP-BNI5 under ADH1 promoter control). The transformants were grown overnight at 23°C, and half of each culture was shifted to 37°C for 30 min before fixing the cells.

For each sample, the percentage of budded cells with localized YFP-Cdc10p or YFP-Bni5p signal at the mother-bud neck was determined by examining at least 200 budded cells.

We next asked if Bni5p interacts physically with Cdc11p or other septins. In two-hybrid assays, Bni5p interacted with Cdc11p and perhaps with Cdc12p, but not with Cdc3p or Cdc10p (Fig. 7A). In addition, in vitro binding studies showed that GST-Cdc11p interacted with in vitro-translated T7-Bni5p-His6 (Fig. 7B). Under the same conditions, GST-Cdc3p, GST-Cdc10p, and GST-Cdc12p, but not GST alone, also interacted with Bni5p at a somewhat lesser level (Fig. 7B). In a second experiment, we observed that GST-Cdc11p, but not GST alone, could interact with bacterially expressed, partially purified, T7-Bni5p-His6 (Fig. 7C). Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that Bni5p interacts directly with Cdc11p and perhaps also with the other septins.

To investigate which domain(s) of Cdc11p may be important for the interaction with Bni5p, and hence for Bni5p localization, we integrated into strain KLY1718 (cdc11Δ with a GAL1-GST-CDC11 plasmid) various HA-tagged Cdc11p constructs under normal CDC11 promoter control (Fig. 6B and C). These strains were then transformed with a plasmid expressing either ADH1-YFP-BNI5 or YFP-CDC10. Cells were fixed after depleting GST-Cdc11p by growth in 2% glucose for 1 h, and the percentages of budded cells with neck-localized YFP-Bni5p or YFP-Cdc10p were determined. In strains expressing either full-length Cdc11p1-415 or Cdc11p1-385, YFP-Bni5p was detectable at approximately 90% of the necks in budded cells (Fig. 6D). This result is striking because Cdc11p1-385 lacks a canonical leucine zipper motif (Leu384-X6-Leu391-X6-Leu398-X6-Leu405) that comprises about half of the 57-amino-acid coiled-coil domain predicted by the Coils program (44). In contrast, YFP-Bni5p localization was greatly diminished or abolished in the strains expressing Cdc11p31-385 or Cdc11p1-200 (Fig. 6D), even though these proteins were expressed at levels comparable to those of the others (Fig. 6C). Under the same conditions, YFP-Cdc10p localization at the bud neck was consistently detected in all the strains (Fig. 6D). These data suggest that the N-terminal region (amino acids 1 to 385) of Cdc11p is sufficient for Bni5p localization and that the C-terminal coiled-coil domain is not involved in this event.

Apparently normal function of Cdc11p lacking the coiled-coil domain.

The neck localization of Bni5p in the Cdc11p1-385 cells suggested that Cdc11p1-385 itself also localizes to the neck. Indeed, immunostaining revealed that Cdc11p1-385 localized to the neck as well as did the full-length protein, whereas the other mutant Cdc11p proteins did not (Fig. 6D and E). We then examined the abilities of the Cdc11p truncation mutants to complement the cdc11Δ growth defect. Consistent with the localization data, Cdc11p1-385 appeared to complement the growth defect as well as did the full-length protein, while the other truncated proteins did not (Fig. 6F). Finally, we examined whether Cdc11p1-385 could form a complex with other septin proteins. In strains expressing a myc-tagged Cdc3p and either HA-tagged full-length Cdc11p or HA-tagged Cdc11p1-385, immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibodies was equally effective in coprecipitating Cdc3p-myc (Fig. 6G). This observation is consistent with the results of a matrix of two-hybrid tests involving the full-length and partial septin proteins (Table 5). In particular, although no interactions were observed with the C-terminal domain of Cdc11p, the N-terminal domain appeared to be capable of interacting with itself, with the N-terminal domain of Cdc12p, and with Cdc3p and Cdc10p. With regard to possible models of septin assembly (see Discussion), it was also of interest in these experiments that no homotypic interactions were observed with the Cdc3p constructs (although these did interact with other septins) and that the C-terminal domain of Cdc12p appeared to interact well not only with itself but also with the C-terminal domain of Cdc3p (Table 5). Taken together, these data suggest that the predicted coiled-coil domain of Cdc11p is not required for interaction with other septins, for neck localization, or for other vital aspects of Cdc11p function, and that the assembly of septin complexes involves complex interactions involving both the N- and C-terminal portions of the proteins.

DISCUSSION

Interaction of Bni5p with Cdc11p and other septins.

In this study, we have performed an initial characterization of the novel S. cerevisiae protein Bni5p. Multiple lines of evidence indicate that Bni5p interacts with the septin array at the mother-bud neck. First, BNI5 acts as a dosage suppressor of several different temperature-sensitive septin mutations. Second, Bni5p localizes to the neck in a septin-dependent manner. Third, deletion of BNI5 results in partially penetrant defects in septin organization and in the septin-dependent process of cytokinesis, and double mutants containing both bni5Δ and a temperature-sensitive septin mutation display a phenotype that is more severe than those of the single mutants. Fourth, bni5Δ is synthetically lethal with deletion of HOF1/CYK2, a gene whose product appears to interact with the septins and other proteins involved in cytokinesis (31, 36, 55). Finally, both two-hybrid data and GST pull-down experiments suggest that Bni5p interacts directly with Cdc11p, a suggestion supported by the observations that Bni5p is present at the neck in a cdc10Δ or a sep7Δ strain but disappears rapidly from the neck when Cdc11p is depleted in a viable cdc11Δ strain. The GST pull-down experiments also suggest that Bni5p may interact directly, but more weakly, with the other septins.

Although many proteins have now been shown to localize to the mother-bud neck in a septin-dependent manner (26), suggesting a scaffold function for the septin array, there are very few cases in which strong evidence exists for a specific and/or direct interaction with a particular septin. For example, although the available evidence does suggest that Bni4p interacts specifically with Cdc10p (13) and that Gin4p interacts specifically with Cdc3p (40), these putative interactions have not yet been observed with the isolated proteins. Thus, the results with Bni5p are important in suggesting that at least some proteins are recruited to the neck by direct interaction with the septins and that interaction with particular septins (e.g., Cdc11p in the case of Bni5p) may be largely responsible for the recruitment in particular cases.

Possible roles of Bni5p.

Except for the possible coiled-coil domains, the sequence of Bni5p displays no known motifs or other clues to Bni5p function. Nonetheless, the bni5Δ mutant phenotype and the timing and pattern of Bni5p localization allow some speculations about possible functions of this protein. Because Bni5p localizes to the neck only after the septins are already there, it cannot be involved in their initial recruitment or assembly. However, the partial loss of septin localization and aberrant septin rings that are observed in the bni5Δ mutant suggest that Bni5p, like Gin4p, Cla4p, Elm1p, and Nap1p (7, 40, 42), contributes to the organization and/or stability of the septin array. Although the precise nature of the role of Bni5p is not yet clear, one interesting possibility is suggested by a comparison of previous electron and light microscopic observations. Byers and Goetsch observed that the apparent septin filaments were not fully evident by electron microscopy until the bud had emerged and that they seemed to disappear before cytokinesis (9, 10). However, studies using immunofluorescence and GFP-tagged proteins have shown that the septin proteins arrive at the presumptive bud site 10 to 15 min before bud emergence and typically remain at the division site for some time after cytokinesis and cell separation are complete (21, 33, 36). Thus, the localization of Bni5p to the neck at about the time of bud emergence and its abrupt disappearance just before cytokinesis suggest that it might be involved in the assembly of the higher-order septin structure that gives the appearance of filaments in the electron microscope. Because it does not appear that this higher-order structure is necessary for most aspects of septin function (22, 40), the nonlethality of the bni5Δ mutation is consistent with this hypothesis.

Another interesting possibility is suggested by the recent evidence that activation of the GTPase Tem1p triggers splitting of the septin array, an event that immediately precedes, and may be a prerequisite for, contraction of the actomyosin ring during cytokinesis (38). Thus, the timing of Bni5p delocalization suggests that it might be a Tem1p target, the dissociation of which from the septins is necessary for the splitting of the septin array. However, Tem1p presumably has at least one other relevant target, because most cells of a bni5Δ mutant appear to have a continuous septin array and to complete cytokinesis normally.

In elucidating the role(s) of Bni5p, it will also be necessary to account for the apparent lack of Bni5p homologues in other organisms. Particularly striking is the lack of an unequivocal homologue in Candida albicans, which also reproduces by budding and has a septin family whose sequences and assembly seem very similar to those in S. cerevisiae (15, 23, 57). However, it remains possible that improvements in the annotation of the C. albicans sequence will resolve this apparent paradox.

Roles of the predicted coiled-coil domains in septin assembly and function.

Most of the known septins contain predicted coiled-coil domains at or near their C termini (39), and one simple model for septin assembly suggested that these domains might function in the formation of septin homodimers that were subunits of the heteromeric complexes (19). This model is difficult to reconcile with the dimensions of septin complexes isolated from cdc10Δ and cdc11Δ strains (22). In addition, we have shown here that Cdc11p1-385 (which lacks the leucine zipper motif that comprises about half of the predicted coiled-coil domain) is able to associate with Cdc3p and localize apparently normally to the mother-bud neck. Moreover, in two-hybrid tests, a fragment of Cdc11p lacking the entire predicted coiled-coil domain was able to self-associate, whereas a fragment of 74 amino acids that included the entire 57-amino-acid predicted coiled-coil domain was not. Indeed, taken as a whole, the two-hybrid data (see also reference 14) suggest that the assembly of septin complexes involves a complicated set of both homomeric and heteromeric interactions that involve both the N-terminal and C-terminal domains. Higher-resolution structural data will presumably be necessary to clarify the details of septin complex assembly.

The septin coiled-coil domains may also be involved in interactions with the many proteins that are recruited to the neck in a septin-dependent manner (26). In this regard, however, it is striking that Cdc11p1-385 was able not only to recruit Bni5p to the neck but also to rescue fully the growth defect of a cdc11Δ mutant. In addition, the two-hybrid data suggest that the coiled-coil domain of Cdc12p may be involved both in homomeric interactions and in interactions with the coiled-coil domain of Cdc3p. Additional structure-function studies of the various septins and the septin-interacting proteins will be necessary to clarify these issues.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

Consistent with the results reported here, Mortensen et al. have recently noted the presence of Bni5p in isolated protein complexes that contain also the septins Gin4p and Nap1p (E. M. Mortensen, H. McDonald, J. Yates III, and D. R. Kellogg, Mol. Biol. Cell 13:2091-2105, 2002).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Christine Field and Jeremy Thorner for valuable discussions; Yeon-Sun Seong, Young-Wook Cho, and Dan Ilkovitch for technical support; and Jason Chong for assistance in the initial identification of BNI5. We also thank Susan Garfield for helping with confocal microscopy and Jim McNally and Tatiana Karpova for processing confocal images obtained at the LRBGE Fluorescence Imaging Facility at NCI.

This work was supported in part by grants NIH GM59964 (R.L.) and NIH GM31006 (J.R.P.).

P.R.L., S.S., and H.-S.R. contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, A. E. M., and J. R. Pringle. 1984. Relationship of actin and tubulin distribution to bud growth in wild-type and morphogenetic-mutant Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 98:934-945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1995. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., New York, N.Y.

- 3.Barral, Y., V. Mermall, M. S. Mooseker, and M. Snyder. 2000. Compartmentalization of the cell cortex by septins is required for maintenance of cell polarity in yeast. Mol. Cell 5:841-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barral, Y., M. Parra, S. Bidlingmaier, and M. Snyder. 1999. Nim1-related kinases coordinate cell cycle progression with the organization of the peripheral cytoskeleton in yeast. Genes Dev. 13:176-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bi, E., P. Maddox, D. J. Lew, E. D. Salmon, J. N. McMillan, E. Yeh, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Involvement of an actomyosin contractile ring in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 142:1301-1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boeke, J. D., F. Lacroute, and G. R. Fink. 1984. A positive selection for mutants lacking orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoro-orotic acid resistance. Mol. Gen. Genet. 197:345-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouquin, N., Y. Barral, R. Courbeyrette, M. Blondel, M. Snyder, and C. Mann. 2000. Regulation of cytokinesis by the Elm1 protein kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Sci. 113:1435-1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourne, H. R., D. A. Sanders, and F. McCormick. 1991. The GTPase superfamily: conserved structure and molecular mechanism. Nature 349:117-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byers, B. 1981. Cytology of the yeast life cycle, p. 59-96. In J. N. Strathern, E. W. Jones, and J. R. Broach (ed.), The molecular biology of the yeast Saccharomyces: life cycle and inheritance. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 10.Byers, B., and L. Goetsch. 1976. A highly ordered ring of membrane-associated filaments in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 69:717-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll, C. W., R. Altman, D. Schieltz, J. R. Yates, and D. Kellogg. 1998. The septins are required for the mitosis-specific activation of the Gin4 kinase. J. Cell Biol. 143:709-717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chant, J., M. Mischke, E. Mitchell, I. Herskowitz, and J. R. Pringle. 1995. Role of Bud3p in producing the axial budding pattern of yeast. J. Cell Biol. 129:767-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeMarini, D. J., A. E. M. Adams, H. Fares, C. De Virgilio, G. Valle, J. S. Chuang, and J. R. Pringle. 1997. A septin-based hierarchy of proteins required for localized deposition of chitin in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall. J. Cell Biol. 139:75-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Virgilio, C., D. J. DeMarini, and J. R. Pringle. 1996. SPR28, a sixth member of the septin gene family in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that is expressed specifically in sporulating cells. Microbiology 142:2897-2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiDomenico, B. J., N. H. Brown, J. Lupisella, J. R. Greene, M. Yanko, and Y. Koltin. 1994. Homologs of the yeast neck filament associated genes: isolation and sequence analysis of Candida albicans CDC3 and CDC10. Mol. Gen. Genet. 242:689-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edgington, N. P., M. J. Blacketer, T. A. Bierwagen, and A. M. Myers. 1999. Control of Saccharomyces cerevisiae filamentous growth by cyclin-dependent kinase Cdc28. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:1369-1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fares, H., L. Goetsch, and J. R. Pringle. 1996. Identification of a developmentally regulated septin and involvement of the septins in spore formation in S. cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 132:399-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Field, C., R. Li, and K. Oegema. 1999. Cytokinesis in eukaryotes: a mechanistic comparison. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11:68-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Field, C. M., O. Al-Awar, J. Rosenblatt, M. L. Wong, B. Alberts, and T. J. Mitchison. 1996. A purified Drosophila septin complex forms filaments and exhibits GTPase activity. J. Cell Biol. 133:605-616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Field, C. M., and D. Kellogg. 1999. Septins: cytoskeletal polymers or signalling GTPases? Trends Cell Biol. 9:387-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford, S. K., and J. R. Pringle. 1991. Cellular morphogenesis in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell cycle: localization of the CDC11 gene product and the timing of events at the budding site. Dev. Genet. 12:281-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frazier, J. A., M. L. Wong, M. S. Longtine, J. R. Pringle, M. Mann, T. J. Mitchison, and C. Field. 1998. Polymerization of purified yeast septins: evidence that organized filament arrays may not be required for septin function. J. Cell Biol. 143:737-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gale, C., M. Gerami-Nejad, M. McClellan, S. Vandoninck, M. S. Longtine, and J. Berman. 2001. Candida albicans Int1p interacts with the septin ring in yeast and hyphal cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:3538-3549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gietz, R. D., and A. Sugino. 1988. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene 74:527-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giot, L., and J. B. Konopka. 1997. Functional analysis of the interaction between Afr1p and the Cdc12p septin, two proteins involved in pheromone-induced morphogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 8:987-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gladfelter, A. S., J. R. Pringle, and D. J. Lew. 2001. The septin cortex at the yeast mother-bud neck. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:681-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guan, K. L., and J. E. Dixon. 1991. Eukaryotic proteins expressed in Escherichia coli: an improved thrombin cleavage and purification procedure of fusion proteins with glutathione S-transferase. Anal. Biochem. 192:262-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haarer, B. K., and J. R. Pringle. 1987. Immunofluorescence localization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC12 gene product to the vicinity of the 10-nm filaments in the mother-bud neck. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:3678-3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartwell, L. H. 1971. Genetic control of the cell division cycle in yeast. IV. Genes controlling bud emergence and cytokinesis. Exp. Cell Res. 69:265-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill, J. E., A. M. Myers, T. J. Koerner, and A. Tzagoloff. 1993. Yeast/E. coli shuttle vectors with multiple unique restriction sites. Yeast 2:163-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamei, T., K. Tanaka, T. Hihara, M. Umikawa, H. Imamura, M. Kikyo, K. Ozaki, and Y. Takai. 1998. Interaction of Bnr1p with a novel Src homology 3 domain-containing Hof1p. Implication in cytokinesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 273:28341-28345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kartmann, B., and D. Roth. 2001. Novel roles for mammalian septins: from vesicle trafficking to oncogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 114:839-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim, H. B., B. K. Haarer, and J. R. Pringle. 1991. Cellular morphogenesis in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell cycle: localization of the CDC3 gene product and the timing of events at the budding site. J. Cell Biol. 112:535-544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, K. S., T. Z. Grenfell, F. R. Yarm, and R. L. Erikson. 1998. Mutation of the polo-box disrupts localization and mitotic functions of the mammalian polo kinase Plk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:9301-9306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee, K. S., and D. E. Levin. 1992. Dominant mutations in a gene encoding a putative protein kinase (BCK1) bypass the requirement for a Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein kinase C homolog. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:172-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lippincott, J., and R. Li. 1998. Dual function of Cyk2, a cdc15/PSTPIP family protein, in regulating actomyosin ring dynamics and septin distribution. J. Cell Biol. 143:1947-1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lippincott, J., and R. Li. 1998. Sequential assembly of myosin II, an IQGAP-like protein, and filamentous actin to a ring structure involved in budding yeast cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 140:355-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lippincott, J., K. B. Shannon, W. Shou, R. J. Deshaies, and R. Li. 2001. The Tem1 small GTPase controls actomyosin and septin dynamics during cytokinesis. J. Cell Sci. 114:1379-1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Longtine, M. S., D. J. DeMarini, M. L. Valencik, O. S. Al-Awar, H. Fares, C. De Virgilio, and J. R. Pringle. 1996. The septins: roles in cytokinesis and other processes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 8:106-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Longtine, M. S., H. Fares, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Role of the yeast Gin4p protein kinase in septin assembly and the relationship between septin assembly and septin function. J. Cell Biol. 143:719-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Longtine, M. S., C. L. Theesfeld, J. N. McMillan, E. Weaver, J. R. Pringle, and D. J. Lew. 2000. Septin-dependent assembly of a cell cycle-regulatory module in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:4049-4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lupas, A. 1996. Coiled coils: new structures and new functions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 21:375-382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lupas, A., M. V. Dyke, and J. Stock. 1991. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science 252:1162-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mino, A., K. Tanaka, T. Kamei, M. Umikawa, T. Fujiwara, and Y. Takai. 1998. Shs1p: a novel member of septin that interacts with Spa2p, involved in polarized growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 251:732-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sherman, F., G. R. Fink, and J. B. Hicks. 1986. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 47.Shulewitz, M. J., C. J. Inouye, and J. Thorner. 1999. Hsl7 localizes to a septin ring and serves as an adapter in a regulatory pathway that relieves tyrosine phosphorylation of Cdc28 protein kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:7123-7137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122:19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siliciano, P. G., and K. Tatchell. 1984. Transcription and regulatory signals at the mating type locus in yeast. Cell 37:969-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song, S., T. Z. Grenfell, S. Garfield, R. L. Erikson, and K. S. Lee. 2000. Essential function of the polo box of Cdc5 in subcellular localization and induction of cytokinetic structures. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:286-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song, S., and K. S. Lee. 2001. A novel function of Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC5 in cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 152:451-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spellman, P. T., G. Sherlock, M. Q. Zhang, V. R. Iyer, K. Anders, M. B. Eisen, P. O. Brown, D. Botstein, and B. Futcher. 1998. Comprehensive identification of cell cycle-regulated genes of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by microarray hybridization. Mol. Biol. Cell 9:3273-3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Straight, A. F., W. F. Marshall, J. W. Sedat, and A. W. Murray. 1997. Mitosis in living budding yeast: anaphase A but no metaphase plate. Science 277:574-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takizawa, P. A., J. L. DeRisi, J. E. Wilhelm, and R. D. Vale. 2000. Plasma membrane compartmentalization in yeast by messenger RNA transport and a septin diffusion barrier. Science 290:341-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vallen, E. A., J. Caviston, and E. Bi. 2000. Roles of Hof1p, Bni1p, Bnr1p, and Myo1p in cytokinesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:593-611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Waddle, J. A., T. S. Karpova, R. H. Waterston, and J. A. Cooper. 1996. Movement of cortical actin patches in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 132:861-870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Warenda, A. J., and J. B. Konopka. Septin function in Candida albicans morphogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:2732-2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]