Abstract

The general transcription factor TFIIB plays a central role in the selection of the transcription initiation site. The mechanisms involved are not clear, however. In this study, we analyze core promoter features that are responsible for the susceptibility to mutations in TFIIB and cause a shift in the transcription start site. We show that TFIIB can modulate both the 5′ and 3′ parameters of transcription start site selection in a manner dependent upon the sequence of the initiator. Mutations in TFIIB that cause aberrant transcription start site selection concentrate in a region that plays a pivotal role in modulating TFIIB conformation. Using epitope-specific antibody probes, we show that a TFIIB mutant that causes aberrant transcription start site selection assembles at the promoter in a conformation different from that for wild-type TFIIB. In addition, we uncover a core promoter-dependent effect on TFIIB conformation and provide evidence for novel sequence-specific TFIIB promoter contacts.

TFIIB plays a crucial role in preinitiation complex (PIC) assembly, providing a bridge between promoter-bound TFIID and RNA polymerase II (pol II)-TFIIF (reviewed in references 13 and 26). TFIIB is composed of two domains, a core domain with two alpha-helical direct repeats and an N-terminal region that has been shown by nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry to contain a zinc ribbon motif (42). The structure of the core domain of TFIIB (TFIIBc), both as a free entity and in a complex with TATA-binding protein (TBP) and a TATA element, has been elucidated (2, 24). TFIIB makes non-sequence-specific contacts with DNA both upstream and downstream of the TATA box in this structure. In addition, TFIIB can make sequence-specific DNA contact with an element immediately upstream of the TATA box (18, 33, 39). This TFIIB recognition element (BRE) has been reported to be present in a subset of eukaryotic and archaeal promoters. At least one function of this element is to modulate the strength of the core promoter (7, 18, 33). Another function is in the determination of the orientation of the TFIIB-TBP-TATA complex that would project the zinc ribbon of TFIIB towards the transcription initiation site (4, 22, 39).

Present data concerning the structure of TFIIB in a complex with TBP at a promoter have been limited to TFIIBc, which lacks both the zinc ribbon and the highly conserved spacer region. Several studies have reported that the N- and C-terminal regions of TFIIB are engaged in an intramolecular interaction (15, 16, 36, 41). Indeed, conformation plays a critical role in the response of TFIIB to transcriptional activators (15, 37, 41). Thus, present structural models do not help us to understand the role of TFIIB conformation in the assembly of the PIC.

TFIIB plays a central role in transcription start site selection (3, 14, 30). In fact, yeast TFIIB was cloned as the result of a genetic screen that generated a yeast mutant with an altered transcription start site phenotype (30). In addition, the unusual start site selection mechanism (scanner) specific to Saccharomyces cerevisiae is attributable to TFIIB and pol II (10, 19). Studies in archaea have confirmed that the role of TFIIB in transcription start site selection has been conserved through evolution (5). Moreover, the archaeal studies demonstrate that TBP, TFIIB, and pol II are sufficient to support this function of TFIIB. The region of TFIIB involved in transcription start site selection maps to the N terminus of the protein and to a region that is highly conserved between species (32). This is the only region of TFIIB for which we do not have any structural information. This highly conserved region of TFIIB contains several charged residues, which comprise what is here termed a charged cluster domain (CCD), and is involved in maintaining TFIIB conformation (15, 41). Single point mutation of these charged residues causes a shift in the transcription start site at some promoters but not others (3, 5, 8, 14, 28, 30, 31). The transcription start site shift has, so far, always been shown to be downstream of normal, indicating that TFIIB measures the 3′ parameter of the transcription initiation window (reviewed in reference 13). Human TFIIB transcription start site mutants do not show a quantitative difference from wild-type TFIIB in their ability to support transcription or interact with TBP, pol II, or TFIIF (14, 15). Thus, the mechanism by which TFIIB modulates transcription start site selection is not known.

In the present study, we analyzed promoter derivatives to determine the features of the core promoter that render it sensitive to transcription start site shift by TFIIB mutants. In addition, using epitope-specific antibodies, we analyzed the conformation of TFIIB in a TFIIB-TBP complex assembled in a collection of promoters. We found that the conformation of TFIIB in a promoter-bound complex is altered by a mutation in TFIIB that perturbs transcription start site selection. Moreover, we found that the conformation of TFIIB assembled at a promoter can be modulated by sequence-specific TFIIB-DNA contact.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

The promoter DNA templates G5E4T and G5ML have been described previously (14, 21). G5HIVLTR and G5IGFII contain nucleotides −45 to +15 of the human immunodeficiency virus long terminal repeat (HIV LTR) and nucleotides −50 to +30 of the human IGFII (hIGFII) P3 promoters cloned downstream of five GAL4 DNA-binding sites in pGEM3 (Promega). These core promoters and also the E4ML and MLE4 hybrids were synthesized as oligonucleotides flanked by restriction enzyme sites recognized by BamHI and EcoRI. pET TFIIB, pET TFIIB E51R, pET TFIIB (C34A), pET TFIIB (Δ4-85), PTAC GAL4-AH, and pET6His-TBP have been described previously (12, 14, 17, 20).

Protein purification and transcription assay.

Recombinant TFIIB and derivatives were purified from Escherichia coli as native proteins as described previously (12). GAL4-AH was purified as described previously (20). Six-His TBP was purified by nickel chelate affinity chromatography as recommended by the manufacturer (Qiagen). HeLa cell nuclear extracts were purchased from the Computer Cell Culture Centre (Mons, Belgium). TFIIB-depleted nuclear extract was produced by chromatography of HeLa nuclear extract over a column containing anti-TFIIB polyclonal antibodies. TFIIA was purified from HeLa nuclear extract by phosphocellulose, Q-Sepharose, and nickel chelate affinity chromatography as described previously (9). Transcription assays were performed as described previously (20).

DNA-binding assays.

DNA probes were radiolabeled by Klenow fragment fill in with [α-32P]dATP of the appropriate promoter fragment. All probes were gel purified. Bandshift assays were performed as described previously (23). Where indicated, antibodies were added to the reaction mix at the same time as the other components of the reaction. Protein-DNA complexes were resolved on a 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gel. Methylation interference analysis was performed as described previously (1). Briefly, complexes were formed and resolved as for a bandshift assay, except that the probe was in excess and was partially methylated with dimethyl sulfate prior to use. Complexes were excised from the gel, eluted, and subjected to cleavage with piperidine. Samples were precipitated and resolved by electrophoresis through a 12.5% denaturing PAGE gel. For DNase I footprinting assays, complexes were formed as for electrophoretic mobility shift assays in a 12-μl reaction volume and then 12 μl of salt mix (10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM CaCl2) was added. DNase I was added, and the reaction was allowed to proceed for 90 s before being stopped by the addition of 1× PK buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 25 mM EDTA, 300 mM NaCl, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]), 10 μg of proteinase K/ml, and 10 μg of tRNA. Samples were incubated at 55°C for 15 min and then phenol-chloroform extracted and precipitated with isopropanol. Samples were then resuspended in formamide loading dye and resolved as described above.

Antibodies and immunodetection.

Anti-TFIIB polyclonal antibodies raised against full-length recombinant TFIIB have been described previously (14). The peptides shown in Fig. 4 were synthesized by Graham Bloomberg, University of Bristol (Bristol, United Kingdom). The sequences of the peptides were NHPDAILVEDYRAG, ECGLVVGDRVIDVGSEWR, and TFSNDKATKDPSRVGD. The peptides were attached to keyhole limpet cyanin and used to immunize sheep (Scottish Antibody Production Unit). The antibodies were purified using a specific peptide that had been linked to activated Sepharose (Amersham-Pharmacia). For immunoprecipitation, bacterial lysates containing recombinant TFIIB (or TFIIB E51R) were incubated at 4°C for 1 h in 1 ml of buffer D (20 mM HEPES [pH 8], 20% glycerol, 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) with 200 ng of purified antipeptide antibody, 1 μl of anti-TFIIB antiserum, or 1 μl of preimmune serum. Twenty microliters of protein G-Sepharose (Amersham-Pharmacia) was added, and the incubation was continued for 1 h. The beads were then washed four times in buffer D, and bound proteins were eluted in SDS-PAGE loading dye. After resolution by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore), TFIIB was detected by immunoblotting with anti-TFIIB antibody.

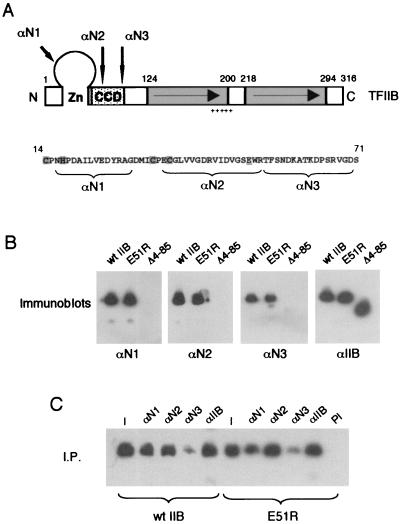

FIG. 4.

Generation and characterization of epitope-specific anti-TFIIB antibodies. (A) Diagram of TFIIB showing the zinc ribbon (Zn), CCD, and direct repeats. Peptides were synthesized as indicated in the sequence below the diagram (see Materials and Methods). Antibodies were raised to these peptides (αN1, αN2, and αN3), and the epitopes are positioned on the TFIIB schematic. The plus signs represent the basic amphipathic α-helix in the first direct repeat of TFIIB. (B) Immunoblots using αIIB and the epitope-specific antibodies from panel A. Lanes of the blots containing wild-type TFIIB, the TFIIB point mutant E51R, and the TFIIB deletion mutant Δ4-85 are indicated. (C) Immunoprecipitation (I.P.) with αIIB and the epitope-specific antibodies (αN1, αN2, and αN3). Lane I, 1/20 of the input in each immunoprecipitation; lane PI, control immunoprecipitation with preimmune serum.

RESULTS

TFIIB determines both the 5′ and 3′ parameters of transcription start site selection in an initiator-dependent manner.

It was shown previously that the TFIIB mutant E51R causes a downstream shift in the transcription start site at the AdE4 promoter but not the AdML promoter (14) (Fig. 1A). The AdML promoter largely initiates transcription at the consensus A (+1) of the initiator region (INR) sequence. The +1 A of the INR is also a major transcription initiation site at the AdE4 promoter, but several additional start sites are used both upstream and downstream. The AdE4 promoter contains a pyrimidine-rich sequence upstream of the initiator that may contribute to both the heterogeneity of the transcription start site and the susceptibility to shifting in the presence of TFIIB E51R. In addition, the AdE4 promoter contains a repeated TATA sequence, providing potential for more than one site for the assembly of TFIID.

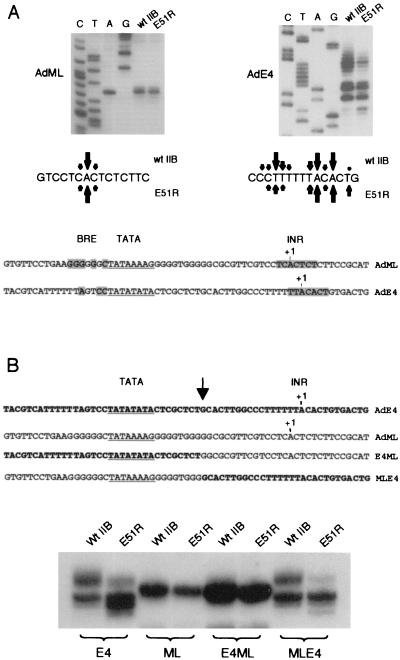

FIG. 1.

The AdE4 INR is responsible for its sensitivity to the TFIIB mutant E51R. (A) The transcription start sites of the AdML and AdE4 promoters were mapped by resolving transcripts alongside a sequencing ladder. Transcription assays were performed by supplementing TFIIB-depleted nuclear extract with either recombinant wild-type TFIIB (wt IIB) or the TFIIB mutant E51R. All transcription reactions contained the activator GAL4-AH. Below the autoradiograms, the sequence around the initiator is shown, with arrows indicating the relative use of the transcription start sites with wild-type TFIIB (above) or TFIIB E51R (below). The sequences of the AdML and AdE4 core promoters are shown at the bottom, with conservation of the indicated sequence elements shaded: BRE, 5′ G/C G/C G/A C G C C-3′ (18); INR, C/T C/T A N T/A C/T C/T (38). (B) Mapping was done as described for panel A, except that the AdML and AdE4 (bold) hybrid constructs were used. E4ML contained the AdE4 TATA region and the AdML INR. MLE4 contained the AdML TATA region and the AdE4 INR. An arrow indicates the joining sites of the hybrid promoters.

In order to test if the AdE4 INR or the AdE4 TATA element was directly responsible for the shift in the transcription initiation site caused by TFIIB E51R, we constructed the hybrid promoters shown in Fig. 1B. The hybrids contain the AdE4 TATA element linked to the AdML INR (E4ML) or the AdML TATA element linked to the AdE4 INR (MLE4) and were directly compared in transcription assays with the intact AdE4 and AdML promoters (Fig. 1B). In the presence of wild-type TFIIB, the pattern of transcription from the hybrid promoters was directly attributable to the INR sequence and did not appear to be influenced by the TATA region. Specifically, the E4ML hybrid utilized the same transcription start sites as the AdML promoter and the MLE4 hybrid utilized the same transcription start sites as the AdE4 promoter. These data rule out the possibility that the AdE4 double TATA sequence contributes to the broad range of transcription start sites at this promoter. Furthermore, the ability of the TFIIB mutant E51R to cause a downstream shift in the transcription start site was entirely dependent upon the presence of the AdE4 INR.

To gain more insight into the role of TFIIB in transcription start site selection, we selected two other different promoters (Fig. 2): the hIGFII promoter, which contains a BRE-like sequence upstream of the TATA element of similar conservation to that of the AdML promoter, and the HIV LTR, which lacks a consensus BRE that is similar to that for the AdE4 promoter but also does not contain the unusual TATA motif of the AdE4 promoter. The transcription start sites of these two promoters were examined in the presence of wild-type TFIIB and the mutant E51R. In the presence of wild-type TFIIB, the hIGFII promoter predominantly initiated transcription from either of two juxtaposed nucleotides. Transcription at the hIGFII promoter in the presence of the TFIIB mutant E51R showed neither a significant quantitative effect nor any change in the transcription start sites. The HIV LTR, although initiating the vast majority of RNA synthesis at two juxtaposed nucleotides, exhibited minor upstream and downstream transcription start sites. The TFIIB mutant E51R caused a significant shift in the transcription start site of the HIV LTR. However, surprisingly and in contrast to that by the AdE4 promoter, the shift in transcription start site caused by TFIIB E51R was upstream of normal. Thus, TFIIB can modulate both the 5′ and 3′ parameters of transcription start site selection.

FIG. 2.

TFIIB E51R can cause an upstream shift in transcription start site selection. The transcription start sites of the hIGFII and HIV LTR core promoters were mapped in the presence of wild-type TFIIB (wt IIB) and the TFIIB mutant E51R, as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The sequences of the core promoters are shown below the autoradiogram.

The initiator sequence determines the sensitivity to TFIIB mutants that can alter the transcription start site.

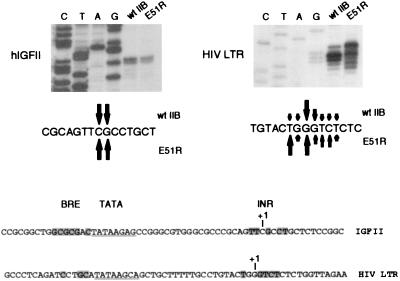

Our results so far suggest that the INR of the promoter is responsible for the ability of the TFIIB mutant E51R to modulate transcription start site selection. To examine this further, we constructed a series of single point mutations within the INR of the HIV LTR (Fig. 3). The transcription start sites utilized by these mutants were compared in the presence of wild-type TFIIB and TFIIB E51R. The results of this analysis revealed two surprising observations. First, single point mutations within the INR can drastically alter the use of surrounding nucleotides as transcription start sites. Second, the precise effect of the TFIIB mutant E51R on transcription start site selection is dependent on the sequence of the INR. Thus, the wild-type HIV LTR and mutant (+4) showed an upstream shift in the transcription initiation site. In contrast, mutant (+3) showed a downstream shift in the transcription start site in the presence of TFIIB E51R. Perhaps the most striking result was demonstrated by mutants (−2) and (+2), which showed a selective reduction in the use of the centrally located transcription start sites. In addition, TFIIB E51R showed a significant quantitative defect in transcription with the mutant (+1), which actually contains an initiator sequence closer to the consensus than the wild-type HIV LTR. Taken together, our data show that the TFIIB mutant E51R can alter the transcription start site in many ways and also exhibit quantitative defects in transcription, both of which are dependent upon the sequence of the INR.

FIG. 3.

The initiator determines the specific nature of the transcription start site shift caused by TFIIB E51R. The wild-type HIV LTR and a series of single point mutants of the initiator (INR is shown only below the autoradiogram) were compared in transcription assays in the presence of either wild-type TFIIB (Wt IIB) or the TFIIB mutant E51R. Shading of the sequences below the gel indicates the conformity of the derivative to the consensus initiator sequence. Arrows indicate the relative use of each nucleotide as a transcription start site with wild-type TFIIB (above the sequence) and TFIIB E51R (below the sequence).

Analysis of TFIIB conformation in a TFIIB-TBP promoter complex.

Previous studies have shown that TFIIB E51R is not defective in forming a TFIIB-TBP promoter complex or in interaction with either TFIIF or pol II (15). Thus, the transcription start site shift caused by TFIIB E51R cannot easily be explained by a defect in interaction with the transcription machinery. Mutations within the CCD at the N terminus of TFIIB have been shown to modulate the conformation of TFIIB (15, 41). We therefore considered the possibility that the conformation of TFIIB may be critical in determining the transcription start site. We generated three peptides that spanned the zinc ribbon and CCD at the N terminus of TFIIB between residues 16 and 71 (Fig. 4A). These peptides were used to immunize animals, and pure antibodies were produced by peptide affinity chromatography (αN1, αN2, and αN3). In Western blotting assays, all three antibodies recognized intact TFIIB but not a TFIIB derivative that lacks the N terminus (Δ4-85 [Fig. 4B]). However, a pan TFIIB polyclonal antibody (αIIB [Fig. 4B]) recognized both full-length TFIIB and TFIIB Δ4-85. In addition, αIIB, αN1, αN2, and αN3 similarly recognized the TFIIB mutant E51R. All of the antibodies were able to immunoprecipitate both recombinant wild-type TFIIB and TFIIB E51R from a bacterial lysate (Fig. 4C). However, αN3 showed a reduced activity in this assay compared to αN1 and αN2.

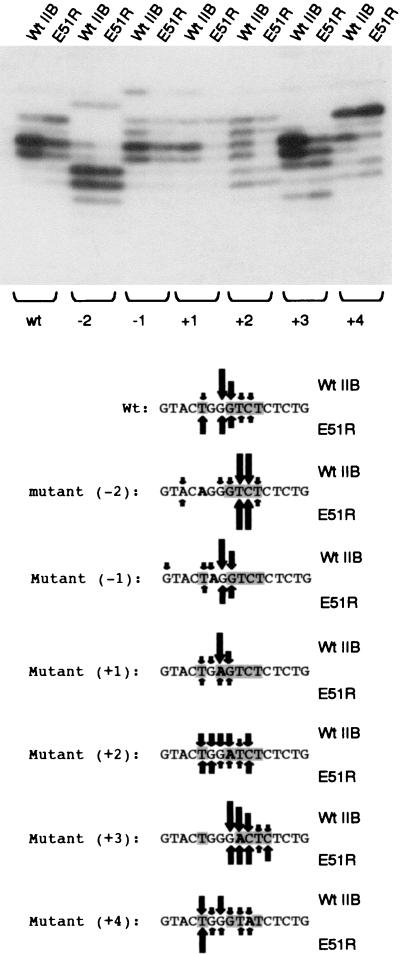

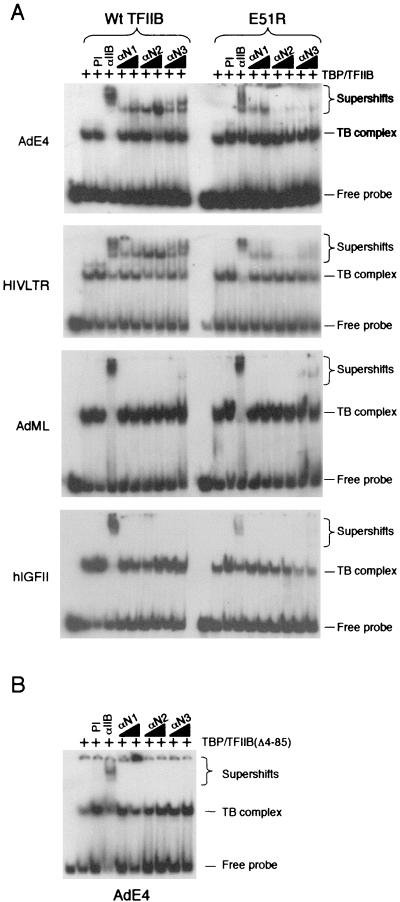

αIIB, αN1, αN2, and αN3 antibodies were next used as probes in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay to monitor their effect on the TFIIB-TBP promoter complex at the AdE4, HIV LTR, AdML, and IGFII core promoters (Fig. 5A). The αIIB antibody supershifted TFIIB-TBP-DNA complexes with all the promoters (Fig. 5A, left). However, all three antipeptide antibodies displayed promoter specificity in their ability to recognize TFIIB in a TFIIB-TBP promoter complex. Specifically, αN1, αN2, and αN3 readily supershifted TFIIB-TBP complexes assembled at the AdE4 and HIV LTR promoters but had little effect with the AdML or IGFII promoters. A TFIIB(Δ4-85)-TBP-AdE4 promoter complex was recognized by the αIIB antibody but not by αN1, αN2, or αN3, confirming the specificity of the antibodies for the N terminus of TFIIB (Fig. 5B). Thus, the four promoters we have described here fall into two distinct categories that present the TFIIB N terminus in two different conformations.

FIG. 5.

TFIIB E51R assembles at the promoter in a conformation different from that to wild-type TFIIB. (A) Bandshift reactions of TFIIB-TBP promoter complexes (left lanes) and TFIIB (E51R)-TBP promoter complexes (right lanes). The four different core promoters are shown. Preimmune serum (PI), αIIB, and epitope-specific TFIIB antibodies (αN1, αN2, and αN3) were added where indicated. Reactions contained 1 ng of TBP, 1 ng of TFIIB, and 10 or 20 ng of purified antibodies (αN1, αN2, and αN3). αIIB and preimmune serum were administered in 0.1-μl volumes. Free probe, TFIIB-TBP promoter (TB) complex, and supershifted complexes are indicated on the right. (B) As described for panel A, except that the TFIIB deletion mutant Δ4-85 and the AdE4 core promoter were used.

To explore the possibility that TFIIB conformation underlies its role in transcription start site selection, we also analyzed the TFIIB derivative E51R in supershift assays with antibodies αN1 through αN3 (Fig. 5A, right). When the complexes contained the TFIIB mutant E51R in place of wild-type TFIIB, the sensitivity to the antibodies changed significantly. Specifically, TFIIB E51R-TBP complexes assembled at the AdE4 and HIV LTR promoters were still sensitive to αN1 though the sensitivity to αN2 and αN3 was severely reduced. The hIGFII and AdML promoters also showed an altered sensitivity to αN3. We also note that the formation of a TFIIB E51R-TBP complex at the hIGFII promoter was disrupted by αN3, indicating a role for the N terminus of TFIIB in stabilizing the TFIIB-TBP-hIGFII promoter complex. Thus, these data demonstrate two determinants of TFIIB conformation assembled at the promoter. First, there is a core promoter sequence-dependent effect on TFIIB conformation. Second, a mutation in TFIIB that causes aberrant transcription start site use shows an altered conformation to wild-type TFIIB when assembled into a promoter complex.

The TATA region determines promoter-dependent TFIIB conformation.

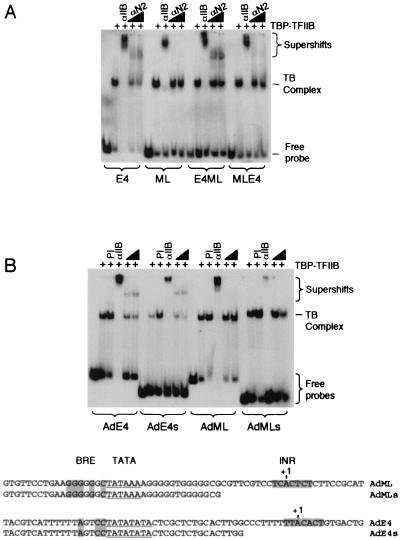

Our results so far have shown that the TFIIB mutant E51R exhibits an altered conformation to wild-type TFIIB when assembled at a promoter. However, we also observed a core promoter-specific effect of the conformation of wild-type TFIIB. We therefore sought to determine if the core promoter-dependent conformation of wild-type TFIIB was linked to the role of TFIIB in transcription start site selection. We assembled TFIIB-TBP complexes at the hybrid promoters shown in Fig. 1B and determined their sensitivity to either αIIB or the epitope-specific αN2 antibody (Fig. 6A). As before, TFIIB assembled at either the AdE4 or AdML promoter was sensitive to αIIB but only the AdE4 was sensitive to αN2. The E4ML hybrid showed sensitivity to αN2, but the MLE4 hybrid did not. These data demonstrate that the determinants of the core promoter-dependent conformation of TFIIB reside within the TATA region of the promoter and not the initiator.

FIG. 6.

The TATA region determines TFIIB conformation. (A) TFIIB-TBP promoter complexes were assembled with the hybrid promoters from Fig. 1B and resolved by native electrophoresis. Preimmune serum (PI), αIIB, or αN2 was included in the reaction where indicated. All amounts of each component are the same as described for Fig. 5. (B) TFIIB-TBP complexes were assembled on the AdE4 and AdML promoters and also truncated versions of these promoters (AdMLs and AdE4s; shown below autoradiogram). Preimmune serum, αIIB, or αN2 was included in the reaction where indicated.

To further analyze the effect of promoter DNA on TFIIB conformation, we produced AdE4 and AdML promoters that were truncated to remove the INR (AdE4s and AdMLs). The promoter derivatives were assembled into TFIIB-TBP complexes that were then resolved by electrophoresis (Fig. 6B). The results show that TBP-TFIIB promoter complexes at the truncated promoters exhibit antibody sensitivity patterns equivalent to those observed at the full-length core promoters. Taken together with the results of the hybrid promoters (Fig. 6A), we concluded that the conformation of TFIIB within the PIC is determined entirely by the TATA region of the promoter. Thus, the combined results shown in Fig. 5 and 6 suggest two independent effects on TFIIB conformation. First, the TATA region of the core promoter modulates the conformation of TFIIB within a TFIIB-TBP promoter complex. Second, the E51R mutation alters the conformation of TFIIB within the promoter-bound complex.

Analysis of sequence-specific interactions between TFIIB and the different core promoters.

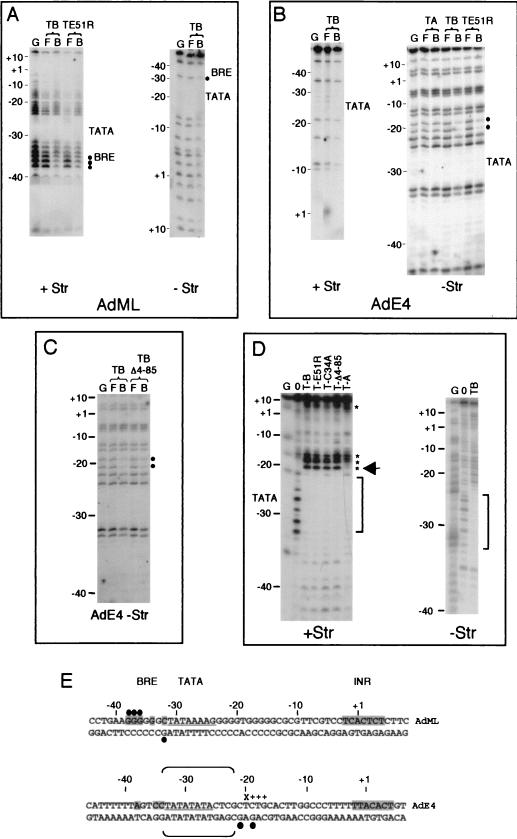

One possible explanation for the promoter-dependent difference in the conformation of promoter-bound TFIIB that we observed may reside in the ability of TFIIB to interact with the core promoter. Indeed, the AdML promoter contains a consensus BRE sequence that has been shown to engage in contact with TFIIB. Moreover, the hIGFII promoter also contains a consensus BRE sequence but the AdE4 and HIV LTR promoters do not. We therefore analyzed TFIIB-TBP complex formation by methylation interference of both strands of the AdML and AdE4 core promoters (Fig. 7A and B). In each case, TFIIB-TBP promoter complexes were formed with partially methylated promoter and the free and bound fractions were separated by electrophoresis and purified. After cleavage with piperidine, the samples were resolved by denaturing electrophoresis alongside a G-track (G) of the same promoter. Bases that exhibited methylation interference are indicated in Fig. 7A through C. Annotated sequences of the promoters are shown in panel E. On the positive strand of the AdML promoter, we observed significant interference of three Gs upstream of the TATA element (−38, −37, and −36 [Fig. 7A]). On the negative strand of the ML promoter, we also observed interference of the G within the BRE immediately upstream of the TATA element (−32). These sequence-specific contacts upstream of the TATA element agree well with previous reports (by other methods) that a helix-turn-helix motif in the second direct repeat of TFIIB recognizes a sequence element upstream of the TATA box (the BRE) (18, 39). Furthermore, the TFIIB mutant E51R showed the same BRE contact as wild-type TFIIB.

FIG. 7.

Extensive DNA sequence recognition by TFIIB. (A) Methylation interference analysis of both the positive strand (+ Str) and negative strand (−Str) of the AdML promoter. The free (F) and bound (B) portions of a TFIIB-TBP promoter complexes (TB) bandshift reaction with partially methylated probe were purified and cleaved with piperidine and resolved by denaturing electrophoresis. A G-track of the promoter (G) is shown, and numbers on the left indicate the positions relative to the transcription start site. The TATA box and BRE are indicated on the right. Nucleotides at which methylation interference has occurred are indicated by filled black circles on the right of the autoradiogram and are reiterated on the sequence in panel E. (B) As described for panel A, except that the AdE4 promoter was used. In addition, methylation interference analysis was performed on TFIIA-TBP-AdE4 complexes (TA). (C) As described for panel A, except that the TFIIB deletion mutant Δ4-85 was compared with the wild-type in TFIIB in methylation interference. (D) DNase I digest analysis of wild-type TFIIB and derivatives assembled with TBP at the AdE4 promoter. On the left is an analysis of the positive strand (+Str), and on the right is an analysis of the negative strand (−Str). DNase I protection is indicated by a bracket, and hypersensitivity is indicated by an asterisk. DNase I hypersensitivity that is specific to TFIIB is indicated by an arrow. TBP-promoter complexes containing the TFIIB point mutants E51R (T-E51R) and C34A (T-C34A) and the deletion mutant TFIIB Δ4-85 (T-Δ4-85) are also shown. DNase I analysis of a TFIIA-TBP-AdE4 complex is also shown (T-A). (E) Summary of the methylation interference and DNase I analysis of the AdML and AdE4 promoters. Solid circles indicate TFIIB-specific methylation interference; plus signs designate DNase I hypersensitivity; X denotes TFIIB-dependent DNase I hypersensitivity. The DNase I protected region is bracketed.

We next tested the AdE4 promoter by methylation interference (Fig. 7B). On the positive strand, we did not observe any interference although we did note that there were few Gs present. However, on the negative strand, we observed interference of two Gs located downstream of the TATA element (−21 and −19). Moreover, a TFIIA-TBP-AdE4 complex did not show any interference of the two Gs downstream of the TATA, demonstrating that these contacts are specific to a TFIIB-TBP complex. Analysis of the TFIIB E51R-TBP-AdE4 complex (TE51R) showed the same sequence-specific contact with the element downstream of the TATA box. We next performed methylation interference with a TFIIB derivative in which the N terminus was deleted (TFIIB Δ4-85), which also showed the same contact with the nucleotides at positions −21 and −19 downstream of the AdE4 TATA box (TBΔ4-85) [Fig. 7C]). Thus, TFIIBc makes sequence-specific DNA contact with an element downstream of the TATA box in the AdE4 promoter. In addition, TFIIBc promoter contact is not affected by a mutation in TFIIB that alters transcription start site selection.

Methylation interference analysis uncovered a core promoter element downstream of the TATA box of the AdE4 promoter that is contacted by TFIIB. We therefore sought to confirm this contact by DNase I analysis on both strands of the AdE4 promoter (Fig. 7D). We observed two significant regions of DNase I hypersensitivity on the positive strand: one immediately downstream of the TATA element and the other close to the INR. The hypersensitivity at the AdE4 promoter around the transcription start site occurred with both the TBP-TFIIB and TBP-TFIIA complexes. However, part of the hypersensitivity in the −20 region of the E4 promoter was specific to the TBP-TFIIB complex. This coincided with the region of TFIIB-dependent methylation interference (Fig. 7E). The TFIIB deletion (Δ4-85) and point (C34A) mutants showed that the hypersensitivity is not due to the zinc ribbon but rather that it is due to the TFIIBc (Fig. 7D). Taken together, methylation interference and DNase I analysis of the AdE4 promoter have uncovered an element downstream of the TATA box that is contacted by TFIIBc.

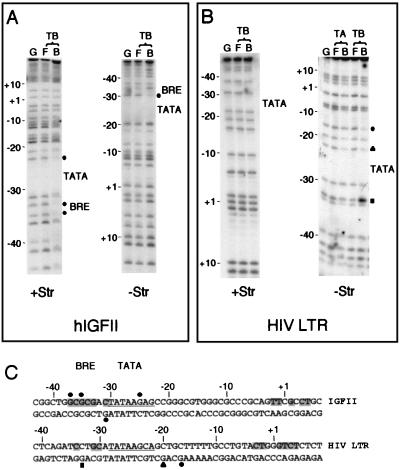

We next performed methylation interference analysis of the hIGFII and HIV LTR core promoters (Fig. 8). Methylation interference analyses of the IGFII promoter confirmed that the BRE-like element upstream of the IGFII TATA element is subject to specific contact at three Gs upstream of the TATA element (two contacts on the positive strand and one contact on the negative strand, at −37, −35, and −31 [Fig. 8A]). Interference was also observed at the G immediately downstream of the TATA element of the IGFII promoter (positive strand at −25). Methylation interference analysis of the HIV LTR revealed two Gs downstream of the TATA element that are crucial to the formation of a TFIIB-TBP complex (at −20 and −17 [Fig. 8B]). The G at −20 (closer to the TATA) was also critical for TFIIA-TBP-HIV LTR complex formation. However, the G at −17 was specifically contacted in the presence of TFIIB. Interestingly, methylation enhancement was observed with the G 5 bases upstream of the TATA element (at position −33) that was also specific for TFIIB. This may have arisen from the proximity to the hydrophobic patch at the C terminus of TFIIB that would lie in this region. From these data, we conclude that, similar to the AdML promoter, the hIGFII promoter contains a BRE that is contacted by TFIIB. In contrast, both the AdE4 and HIV LTR promoters show sequence-specific TFIIB-DNA contact downstream of the TATA element. These data provide a molecular basis for the two distinct conformations of wild-type TFIIB that we observed at these promoters.

FIG. 8.

TFIIB-DNA sequence-specific contacts at the hIGFII and HIV LTR promoters. (A) As described for Fig. 7, except that the hIGFII promoter was used as the probe. (B) As described for Fig. 7, except that the HIV LTR core promoter was used as the probe. In addition, methylation interference of TBP-specific contact is shown as a black triangle, and TFIIB-dependent methylation enhancement is shown as a black square. (C) Annotation of the hIGFII and HIV LTR core promoter sequences to indicate the regions of methylation interference. Solid circles indicate TFIIB-specific interference, triangles indicate TBP-dependent interference, and the square indicates TFIIB-specific methylation enhancement.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used a collection of different core promoters to analyze the function of TFIIB in transcription start site selection. Furthermore, we provided evidence that TFIIB conformation is an important determinant in this process. Several previous studies have shown that TFIIB conformation is critical in the response to upstream transcriptional activators (15, 16, 36, 41). The results presented here suggest that TFIIB conformation can also regulate the basal transcription functions of this general transcription factor.

An additional finding in this study was the extensive DNA sequence-specific contact by TFIIB that affects the conformation of TFIIB when assembled with TBP at the core promoter. Using methylation interference and DNase I analysis, we have found that, in addition to the previously described BRE, TFIIB can make sequence-specific DNA contact with the core promoter downstream of the TATA element. Examination of the sequence that is contacted within the AdE4 and HIV LTR promoters suggests that this is not BRE-like. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the HTH motif within TFIIB contacts the downstream region of the HIV LTR and AdE4 promoters. The presence of two distinct BREs is reminiscent of bacterial sigma factors, which also engage in two sequence-specific interactions with promoter DNA (reviewed in reference 40).

Using epitope-specific antibodies targeted to the highly conserved N-terminal region of TFIIB, we found that TFIIB can exist in at least two distinct conformations within a TFIIB-TBP core promoter complex. The conformation effects that we observed were attributable to the DNA sequence flanking the TATA box. Previous structural studies suggested that the TBP-TATA structure is essentially the same regardless of the sequence of the TATA region (29). Thus, the most likely explanation for our data is that TFIIB-DNA contact can modulate TFIIB conformation within a TFIIB-TBP promoter complex.

It has been demonstrated that TFIIB can engage in an intramolecular interaction between the CCD and the second direct repeat (15, 36, 41). Modulation of the TFIIB intramolecular interaction by assembly into a TBP-TATA complex may therefore underlie the promoter-specific conformation effects we observed. It is interesting to note that the structure of TFIIBc in solution differs from that observed when TFIIBc is assembled into a TBP-TATA complex (2, 24). Indeed, in order for the TFIIB HTH motif to make contact with the BRE, TFIIB must undergo a significant conformational change when assembling into a complex. Small-angle X-ray scattering suggests that the core domain within full-length TFIIB in solution is not in the same conformation as that observed within TFIIBc in solution (11). Instead, the core domain of intact TFIIB appears to exhibit a conformation similar to that observed within TFIIBc in the crystal structure with TBP at the AdML promoter. It is therefore possible that the interaction of TFIIB with the BRE stabilizes the intramolecular interaction. The BRE has been shown to modulate the transcriptional potency of a core promoter (7, 18, 33). Our present data suggest that this may, at least in part, be due to effects on TFIIB conformation.

In addition to the effects of core promoter sequence on TFIIB conformation, we found that the TFIIB mutant E51R assembles at the promoter in a conformation different from that observed for wild-type TFIIB. The N terminus of TFIIB forms a binding site for TFIIF-pol II, which helps to guide pol II into the PIC (12). Previous studies of the TFIIB E51R mutant failed to uncover a defect in its interaction with TFIIF, RNA pol II, or a transcriptional activator protein (15). In addition, TFIIB E51R forms a complex with TBP at the promoter with an affinity equivalent to wild-type TFIIB (15). Studies in yeast in which a similar TFIIB mutant E62K (corresponding to human residue 51) was used also showed no defects in interaction with pol II or in the ability to form a TFIIB-TBP-TFIIF-pol II complex at the promoter (6, 34). Moreover, the archaeon TFIIB mutant E46K (corresponding to human residue 51) did not show any defects in the assembly of a transcription complex or in open complex formation (5). Thus, the finding that human TFIIB E51R exhibits an altered conformation provides a novel mechanism by which TFIIB mutants alter transcription start site selection. It is possible that the altered conformation of TFIIB E51R shifts the location of TFIIF-pol II complex relative to the INR, resulting in a translocation of the pol II catalytic center. This would result in the initiation of transcription at a different nucleotide, although ultimately this is clearly dependent upon the sequence around the initiator and the spacing from the TATA element (27). Moreover, considering that the DNA distorts significantly around the PIC, it is entirely possible that the same alteration in TFIIB conformation can cause either an upstream or downstream shift in the transcription initiation site (25, 35).

Promoter hybrid analysis and point mutation have shown that the INR determines the sensitivity to shifts in the transcription start site caused by the TFIIB mutant E51R. These results are consistent with previous studies in yeast and archaea (5, 8). Our results also show that the sequence of the initiator dictates the nature of the alteration in transcription start site use. Indeed, our data suggest that the effects of TFIIB E51R are manifested as an alteration in specificity rather than a shift 5′ or 3′ per se. These effects are consistent with a translocation of the pol II catalytic center and the presentation of alternative nucleotides at which pol II can initiate. It is also interesting that one of the HIV LTR initiator derivatives (+1) we tested showed a significant quantitative difference in transcription between wild-type TFIIB and TFIIB E51R. The most likely explanation is that TFIIB E51R forms a nonproductive PIC at this promoter derivative. Indeed, the yeast TFIIB mutants E62G and E62K (residue 51 in humans) can support the formation of a complete PIC at a core promoter but transcription initiation is blocked (34). In light of the data presented here, we suggest that the most plausible interpretation of a quantitative transcription defect of TFIIB transcription start site mutants is that pol II is positioned at a sequence that is not acceptable as an INR. This and other possibilities will form the basis of future studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andy Sharrocks, Paul Shore, and members of the lab for comments on the manuscript and also members of the Division of Gene Expression at Dundee University for helpful comments during this study. We are also grateful to Ben Luisi and Tali Haran for many discussions and critiques of the data.

R.E. was supported by a research studentship from the MRC. N.A.H. was the recipient of a BBSRC research studentship. This work was funded by the BBSRC and the Wellcome Trust (061207/Z/00/Z/CH/TG/dr). S.G.E.R. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1995. Short protocols in molecular biology, p. 12.9-12.11. John Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 2.Bagby, S., S. J. Kim, E. Maldonado, K. I. Tong, D. Reinberg, and M. Ikura. 1995. Solution structure of the C-terminal core domain of human TFIIB-similarity to cyclin-A and interaction with TATA-binding protein. Cell 82:857-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bangur, C. S., T. S. Pardee, and A. S. Ponticelli. 1997. Mutational analysis of the D1/E1 core helices and the conserved N-terminal region of yeast transcription factor IIB (TFIIB): identification of an N-terminal mutant that stabilizes TATA-binding protein-TFIIB-DNA complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6784-6793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell, S. D., P. L. Kosa, P. B. Sigler, and S. P. Jackson. 1999. Orientation of the transcription preinitiation complex in Archaea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:13662-13667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell, S. D., and S. P. Jackson. 2000. The role of transcription factor B in transcription initiation and promoter clearance in the Archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. J. Biol. Chem. 275:12934-12940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho, E.-J., and S. Buratowski. 1999. Evidence that transcription factor IIB is required for a post-assembly step in transcription initiation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:25807-25813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans, R., J. A. Fairley, and S. G. E. Roberts. 2001. Activator-mediated disruption of sequence-specific DNA contacts by the general transcription factor TFIIB. Genes Dev. 15:2945-2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faitar, S. L., S. A. Brodie, and A. S. Ponticelli. 2001. Promoter-specific shifts in transcription initiation conferred by yeast TFIIB mutations are determined by the sequence in the immediate vicinity of the start sites. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4427-4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ge, U., E. Martinez, C.-M. Chiang, and R. G. Roeder. 1996. Activator-dependent transcription by mammalian RNA polymerase II: in vitro reconstitution with general transcription factors and cofactors. Methods Enzymol. 274:57-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giardina, C., and J. T. Lis. 1993. DNA melting on yeast RNA polymerase II promoters. Science 261:759-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grossmann, J. G., A. J. Sharff, P. O'Hare, and B. Luisi. 2001. Molecular shapes of transcription factors TFIIB and VP16 in solution: implications for recognition. Biochemistry 40:6267-6274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ha, I., S. G. E. Roberts, E. Maldonado, X. Sun, L.-U. Kim, M. R. Green, and D. Reinberg. 1993. Multiple functional domains of general transcription factor IIB: distinct interactions with two general transcription factors and RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 7:1021-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hampsey, M. 1998. Molecular genetics of the RNA polymerase II general transcription machinery. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:465-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawkes, N. A., and S. G. E. Roberts. 1999. The role of human TFIIB in transcription start site selection in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 274:14337-14343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawkes, N. A., R. Evans, and S. G. E. Roberts. 2000. The conformation of TFIIB modulates the response to transcriptional activators in vivo. Curr. Biol. 10:273-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi, F., R. Ishima, D. Liu, K. I. Tong, S. Kim, D. Reinberg, S. Bagby, and M. Ikura. 1998. Human general transcription factor TFIIB: conformational variability and interaction with VP16 activation domain. Biochemistry 37:7941-7951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmann, A., and R. G. Roeder. 1991. Purification of his-tagged proteins in non-denaturing conditions suggests a convenient method for protein interaction studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:6337-6338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lagrange, T., A. N. Kapanidis, H. Tang, D. Reinberg, and R. H. Ebright. 1998. New core promoter element in RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription: sequence specific DNA binding by transcription factor IIB. Genes Dev. 12:34-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, Y., P. M. Flanagan, H. Tschochner, and R. D. Kornberg. 1994. RNA polymerase II initiation factor interactions and transcription start site selection. Science 263:805-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin, Y.-S., M. Carey, M. Ptashne, and M. R. Green. 1988. GAL4 derivatives function alone and synergistically with mammalian activators in vitro. Cell 54:659-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin, Y. S., and M. R. Green. 1991. Mechanism of action of an acidic transcriptional activator in vitro. Cell 64:971-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Littlefield, O., Y. Korkhin, and P. B. Sigler. 1999. The structural basis for the oriented assembly of a TBP/TFB/promoter complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:13668-13673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maldonado, E., I. Ha, P. Cortes, L. Weis, and D. Reinberg. 1990. Factors involved in specific transcription by mammalian RNA polymerase II: role of transcription factors IIA, IID, and IIB during formation of a transcription-competent complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:6335-6347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nikolov, D. B., H. Chen, E. D. Halay, A. A. Usheva, K. Hisatak, D. K. Lee, R. G. Roeder, and S. K. Burley. 1995. Crystal structure of a TFIIB-TBP-TATA element ternary complex. Nature 377:119-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oelgeschlager, T., C.-M. Chiang, and R. G. Roeder. 1996. Topology and reorganisation of a human TFIID-promoter complex. Nature 382:735-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orphanides, G., T. Lagrange, and D. Reinberg. 1996. The general transcription machinery of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 10:2657-2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Shea-Greenfield, A., and S. T. Smale. 1992. Roles of TATA and initiator elements in determining the start site location and direction of RNA polymerase II transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 267:1391-1402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pardee, T. S., C. S. Bangur, and A. S. Ponticelli. 1998. The N-terminal region of yeast TFIIB contains two adjacent functional domains involved in stable RNA polymerase II binding and transcription start site selection. J. Biol. Chem. 273:17859-17864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patikoglou, G. A., J. L. Kim, L. P. Sun, S.-H. Yang, T. Kodadek, and S. K. Burley. 1999. TATA element recognition by the TATA box-binding protein has been conserved throughout evolution. Genes Dev. 13:3217-3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinto, I., D. E. Ware, and M. Hampsey. 1992. The yeast SUA7 gene encodes a homolog of human transcription factor TFIIB and is required for normal start site selection in vivo. Cell 68:977-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinto, I., W.-H. Wu, J. G. Na, and M. Hampsey. 1994. Characterization of sua7 mutations defines a domain of TFIIB involved in transcription start site selection in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 269:30569-30573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qureshi, S. A., B. Khoo, P. Baumann, and S. P. Jackson. 1995. Molecular cloning of the transcription factor TFIIB homolog from Sulfolobus shibatae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:6077-6081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qureshi, S. A., and S. P. Jackson. 1998. Sequence-specific DNA binding by the S. shibatae TFIIB homolog, TFB, and its effect on promoter strength. Mol. Cell 1:389-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ranish, J. A., N. Yudkovsky, and S. Hahn. 1999. Intermediates in the formation and activity of the RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex: holoenzyme recruitment and a postrecruitment role for the TATA box and TFIIB. Genes Dev. 13:49-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robert, F., M. Douziech, D. Forget, J. M. Egly, J. Greenblatt, Z. F. Burton, and B. Coulombe. 1998. Wrapping of promoter DNA around the RNA polymerase II initiation complex induced by TFIIF. Mol. Cell 2:341-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts, S. G. E., and M. R. Green. 1994. Activator-induced conformational change in general transcription factor TFIIB. Nature 371:717-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts, S. G. E. 2000. Mechanisms of transcription activation and repression domains. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 57:1149-1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smale, S. T., A. Jain, J. Kaufman, K. H. Emami, K. Lo, and I. P. Garraway. 1998. The initiator element: a paradigm for core promoter heterogeneity within metazoan protein-coding genes. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 63:21-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsai, F. T. F., and P. B. Sigler. 2000. Structural basis of preinitiation complex assembly on human Pol II promoters. EMBO J. 19:25-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wosten, M. M. S. M. 1998. Eubacterial sigma factors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22:127-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu, W.-H., and M. Hampsey. 1999. An activation-specific role for transcription factor TFIIB in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2764-2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu, W. L., Q. D. Zeng, C. M. Colangel, L. M. Lewis, M. F. Summers, and R. A. Scott. 1996. The N-terminal domain of TFIIB from Pyrococcus furiosus forms a zinc ribbon. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3:122-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]