Abstract

Background

Educational interventions that support the implementation of complex clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) require substantial time commitments from participants. We conducted a comparative study to evaluate if a 90-minute workshop would increase compliance with the recommendations of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care as well as decrease the ordering of tests not the subject of specific recommendations.

Methods

Eighty-seven family physicians from Quebec participated in the study. Group assignment was initially randomized, but, owing to logistic problems, randomization was not maintained. After unannounced visits, 2 standardized patients coded the physicians' performance of 23 items recommended for inclusion in the periodic health examination (10 for men and 13 for women) and 8 items recommended for exclusion (4 for both men and women). The “exposed” physicians were visited within 4 to 6 months after the workshop. The “nonexposed” physicians were visited within 4 to 6 months after consent was obtained but before they attended the workshop. We used linear regression analysis to determine if exposure to the workshop resulted in improved performance.

Results

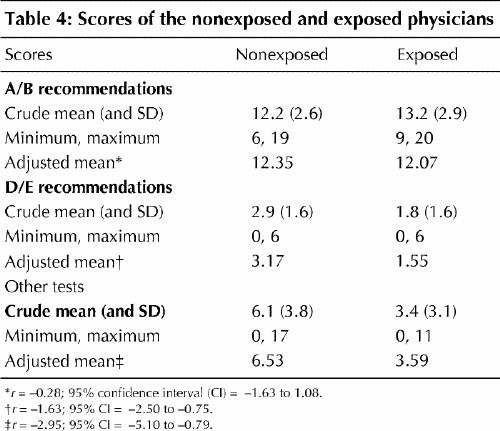

Exposure to the workshop was not associated with a difference in the adjusted mean score for items recommended for inclusion (12.07 for exposed physicians v. 12.35 for those not exposed; maximal and ideal score 23; r = –0.28; 95% confidence interval [CI] = –1.63 to 1.08). However, workshop exposure was associated with lower adjusted mean scores for items recommended for exclusion (1.55 v. 3.17; maximal score 8, ideal score 0; r = –1.63; 95% CI = –2.50 to –0.75) and for other tests (3.59 v. 6.53; r = –2.95; 95% CI = –5.10 to –0.79).

Interpretation

A short workshop can decrease the ordering of unnecessary screening tests by family physicians. Given its low cost and its potential for general application, such an intervention can support the implementation of prevention CPGs.

Reaching health care professionals with information about clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) remains a challenge, particularly in primary care.1 Continuing medical education (CME) is one of the preferred strategies to support the implementation of CPGs.2,3 Interactive workshops have been shown to be effective, sometimes producing moderately large results.4,5 It is not clear which attributes of workshops contribute most to their effectiveness.5 Educational interventions with demonstrated impact require a significant commitment of time, from a full day to a series of sessions. Short workshops, up to 2 hours long, are an interesting alternative, but their effectiveness in modifying complex behaviours has not been established.5

In 1996 the College québécois des médecins de famille and the Collège des médecins du Québec (CMQ) launched a program6 to disseminate to Quebec family physicians the recommendations of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC), known at that time as the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination (PHE).7 The program, which has now been delivered to nearly 1000 family physicians, featured a 90-minute interactive workshop aimed at improving the use of various screening procedures. Could such a brief intervention improve implementation of the CTFPHC recommendations, which involve the modification of a series of behaviours? We conducted a comparative study to evaluate if exposure to the workshop would increase compliance with the recommendations as well as decrease ordering of tests not the subject of specific recommendations.

Methods

Design

We designed a double-blind randomized controlled trial involving unannounced visits by standardized patients (SPs) to family physicians before or after the physicians had been exposed to the workshop. Randomization was not maintained for some of the physicians because of problems with the timing of the SP visits or, less often, lack of attendance at the workshop because of a last-minute change in the physician's schedule. However, blinding was maintained. Thus, the study should be considered a comparative double-blind trial.

The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal's Research Centre.

Study population

Family physicians practising within 150 km of Montreal were recruited through the Quebec CME network. Physicians practising in a clinic where the workshop had not already been offered were sent a letter of invitation with the endorsement of the physician in charge of CME in the clinic. The letter stated that the objective of the trial was to measure the effectiveness of an educational intervention on the PHE and would involve unannounced visits from 2 SPs.

Physicians accepting new patients and not limiting their practice to a particular patient population were eligible. Eligible physicians interested in the study were contacted by the research assistant, who then obtained informed consent. For their participation the physicians were to receive no remuneration but were offered MAINPRO-C credits from the College of Family Physicians of Canada, in addition to the MAINPRO-C credits they would obtain from attending the workshop. With their confirmation letter, participants were given warning cards, which they were asked to return if they suspected an SP visit. Recruitment took place from January 1998 to April 1999.

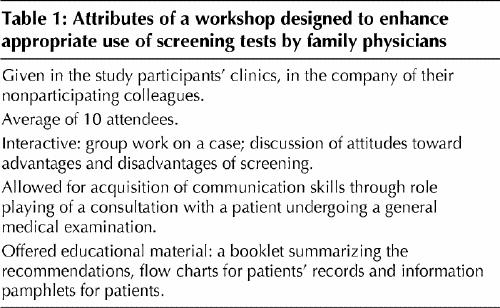

Intervention

The workshop incorporated features of effective educational interventions and addressed known barriers to the implementation of CPGs1,3,4,5,8 and CTFPHC recommendations.9 Its attributes are presented in Table 1. The leaders were trained to ensure a standard presentation. The workshop was pretested with 3 groups of physicians.

Table 1

Group assignment and blinding

The study physicians were randomly assigned to be exposed or not exposed to the intervention by drawings from opaque envelopes by the research assistant. However, since the workshop was given only once at each of the clinics, and all physicians, be they study participants or not, attended the workshop at the same time, it was really the timing of the SPs' visits that was randomized. Thus, if there were 2 participating physicians at a given clinic and one had been assigned to the nonexposed group, he or she should have had the 2 unannounced SP visits before the workshop and could not be “contaminated” by the exposed colleague. The challenge was not to avoid talking among the clinic physicians about the workshop but to avoid talking about the SP visits. The workshop leaders, the SPs and the study physicians remained unaware of the individual physicians' assignments.

Standardized patients

Six men and six women, recruited from advertisements to 3 Montreal senior citizens' groups, were selected on the basis of comparability of relevant physical characteristics (e.g., ethnic origin and weight) and absence of unusual medical conditions. They were paid a small honorarium for their training time and $50 per visit. All their expenses were refunded. The provincial medical insurance board supplied a health insurance card for each SP, and physician payments were reimbursed to the board at the end of the study.

We used 2 scenarios based on a study by Hutchison and colleagues:10 a visit by a recently retired man 55 to 65 years old who had not seen a doctor for 5 years and a visit by a woman 55 to 65 years old who was looking for a new family physician and was worried because one of her friends had just had a heart attack. The SPs were given excuses to avoid rectal and pelvic examinations.

We standardized the scenarios and the coding of physician performance according to previously published methods.11,12,13 The SP visits were audiotaped with a hidden microphone. The research associate periodically verified conformity of the scenarios and coding by listening to the recordings and providing feedback. Every 3 months, all the SPs attended a 2-hour meeting with the research team.

The “exposed” physicians were visited within 4 to 6 months after the workshop. The “nonexposed” physicians were visited within 4 to 6 months after consent was obtained but before they attended the workshop.

Outcome measures

Immediately after each visit the SPs completed a questionnaire, coding the physician's performance of the physical examination and counselling; they also submitted any test requisition forms they had received. Physical abnormalities perceived by physicians during examinations, as reported by SPs, were taken into account as potential confounders.

The primary outcome measures were 2 scores: the total number of items recommended by the CTFPHC7 for inclusion in the PHE (i.e., those having an A/B score because of good or fair evidence to support inclusion) that were performed or ordered during both visits (there were 10 such items for men and 13 for women, for ideal and maximal scores of 23) and the total number of items recommended for exclusion (i.e., those having a D/E score because of good or fair evidence to support exclusion) that were performed during both visits (there were 4 such items for both men and women, for an ideal score of 0 and a maximal score of 8). The secondary outcome measure was the total number of tests ordered that were not the subject of specific recommendations (e.g., measurement of the serum levels of liver enzymes and creatinine), identified as the “other tests” score.

Sample size determination

The rate of performing or ordering A/B items was estimated at 40% and that of D/E items 30%.10 We set the target sample size to demonstrate a 20% increase and a 20% decrease, respectively, with an α error level of 0.05 and a power of 80%. We needed to recruit 135 physicians; assuming a participation rate of 45%,10 we needed to approach 300 eligible physicians.

Statistical analysis

We assessed the validity of the scenarios by calculating the percentage agreement between the scenarios and the SPs' performances. We used the overall percentage agreement and κ statistics to determine the interobserver agreement in coding of physician performance by the SPs and the research associate.14 Multiple linear regression models were adjusted for workshop exposure and for the physician and patient characteristics likely to explain the variation in scores, as well as for interactions between workshop exposure and physician variables.

Results

Study population

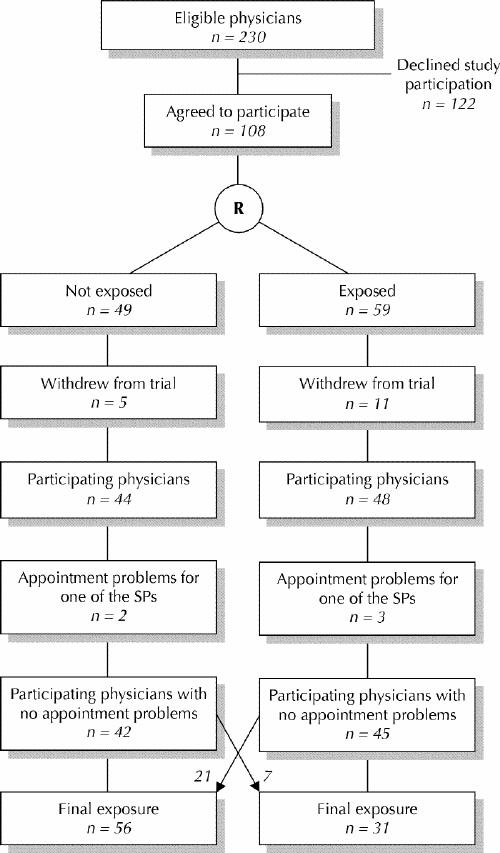

Of the 364 physicians responding to the invitation, 230 were eligible to participate in the study; 108 (47%) of the eligible physicians, from 55 clinics, agreed to participate. Among the eligible physicians those who did not agree to participate were comparable to the participants except that the participants included more graduates of family medicine training programs. Sixteen participants (15%) did not complete the study: 3 withdrew their consent, and 13 stopped accepting new patients before the SPs were ready to visit them. Five physicians saw only one SP each. Therefore, the analyses encompassed 87 physicians. Randomization was broken by change in workshop-exposure status for 21 physicians assigned to the exposed group and 7 physicians assigned to the nonexposed group. This “crossing over” was due almost exclusively to delays in obtaining appointments for SPs within the period set by the random assignment. Also, some physicians could not attend the workshop because of last-minute changes in their schedule. Consequently, the exposed group was composed of 31 physicians and the nonexposed group 56 (Fig. 1). Eight physicians (9%) suspected that 14 visits (8%) were by an SP; these visits were excluded from analysis.

Fig. 1: Recruitment, randomization process and subsequent crossover of study participants. SP = standardized patient.

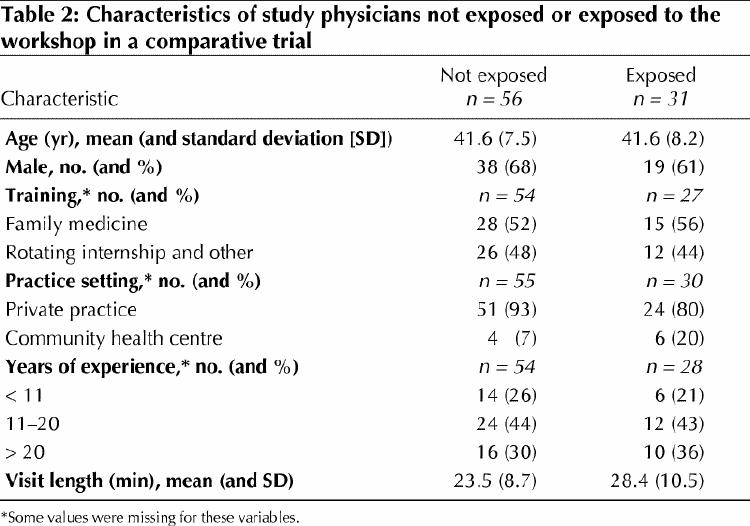

The 2 study groups were comparable except for length of SP visit, which was greater (p = 0.04) for the exposed group (Table 2). The study participants were comparable to the other workshop attendees in terms of demographic and practice variables and evaluation of the workshop. However, the study participants expressed slightly greater agreement with the CTFPHC recommendations (p = 0.03).

Table 2

Validation of scenarios and coding

The degree of conformity with the standard scenarios was high: 93.5% and 84.8% for the female and male SPs, respectively. The degree of conformity in coding was also high: 90.5% (κ = 0.66) for the female SPs and 90.1% (κ = 0.68) for the male SPs.

Effect of workshop on physician performance

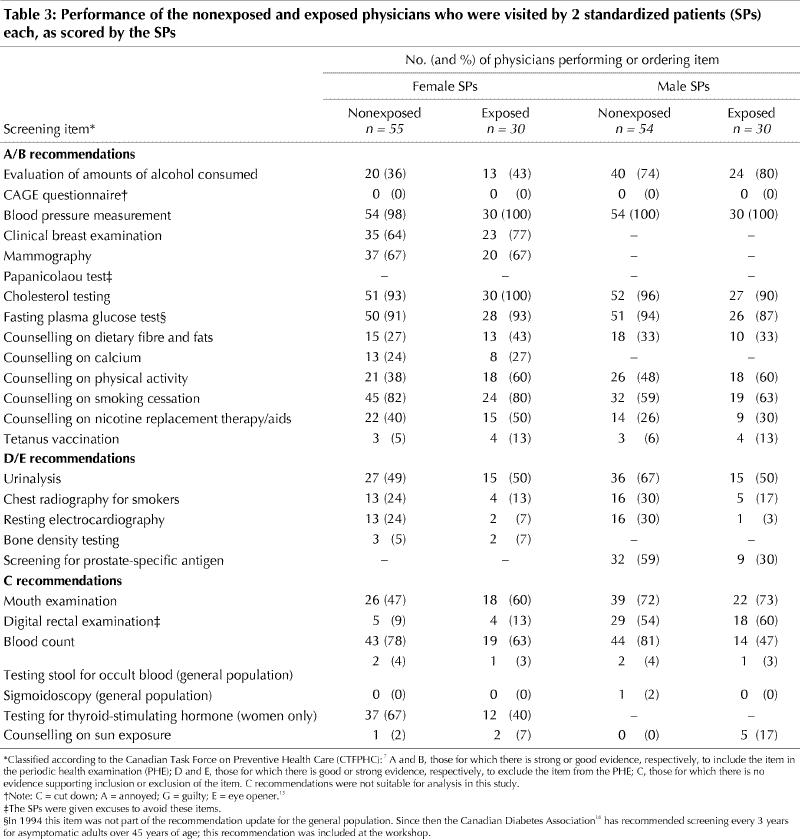

Table 3 summarizes the data on each of the items for which information was collected by the SPs. The CAGE questionnaire,15 for detection of excessive alcohol use (C = cut down; A = annoyed; G = guilty; E = eye opener), was never used. Smoking cessation was addressed more frequently with the women SPs, whose reason for the visit included concern about cardiovascular disease.

Table 3

Exposure to the workshop had no impact on the A/B score (Table 4), the exposed physicians performing or ordering an average of only 0.28 fewer items than the nonexposed physicians (adjusted means 12.07 and 12.35; r = –0.28; 95% confidence interval [CI] = –1.63 to 1.08). However, workshop exposure was the variable with greatest impact on both the D/E score and the “other tests” score: the exposed physicians ordered an average of 1.62 fewer D/E tests (adjusted means 1.55 and 3.17; r = –1.63; 95% CI = –2.50 to –0.75) and 2.94 fewer other tests (adjusted means 3.59 and 6.53; r = –2.95; 95% CI = –5.10 to –0.79).

Table 4

In addition, physicians with less than 11 years of experience ordered an average of 1.32 fewer D/E tests (r = –1.32; 95% CI = –2.32 to –0.32) and 2.59 fewer other tests (r = –2.59; 95% CI = –5.05 to –0.14).

Only length of visit was associated with the A/B score: during visits lasting less than 20 minutes the physicians performed or ordered 1.40 fewer items (r = –1.4; 95% CI = –2.7 to –0.09).

Because the unit of analysis was the physician and not the clinic, we considered the possibility of contamination in the 23 clinics with more than one study participant. In only one instance did a study physician detect an SP in the month preceding visits by SPs to a colleague. It is possible that study participants did not notify us of their suspicion but discussed it with their colleagues. We hypothesized that in that case there would be more homogeneity within the clinics that had more than one study participant. In fact, there were no differences in mean scores and standard deviations between the physicians from multiple-participant clinics and those from single-participant clinics.

Interpretation

Our results suggest that a short interactive workshop can decrease the ordering of unnecessary screening tests for adults who consult for check-ups. This finding could have major implications, given the low cost of the intervention relative to the costs and potential harm of unnecessary tests.

The strengths of this study were the rigour of the SP methodology, the blinding of exposure to the intervention and to the SP coding, and the duration of follow-up. The high conformity of both scenario and coding and the low rate of SP detection confirm that we attained the state of the art in SP methodology.12,13

The main limitation of the study was the failure to maintain randomization. Still, we are confident that no systematic bias occurred, for 3 reasons: the shift from one group to another was not attributable to the intervention, blinding was preserved, and the characteristics of the physicians in the exposed and nonexposed groups were comparable.

Recruiting physicians who were accepting new patients proved to be more difficult than we had expected. CME requiring the participation of many physicians on set dates, particularly if the timing of outcome measurements is an issue, is the most challenging type of intervention.

Our results add to the body of knowledge showing that interactive CME sessions can change professional practice.3,5,17 We had an impact on a relatively complex behaviour with a simple and low-cost intervention. We believe that our workshop was effective because its content was based on a sound understanding of the reasons family physicians are reluctant to implement D/E recommendations,9 it was offered under the auspices of recognized organizations relying on an existing CME structure, and it allowed for acquisition of communication skills through role play. Also important is the fact that it was given in each participant's clinic: in addition to permitting interaction with significant peers during the workshop, this feature may have increased the impact of the intervention by inducing further formal or informal discussion about the content of the workshop.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Robyn Tamblyn, Brian Hutchison and Christel Woodward for sharing with us their knowledge about the standardized-patient methodology. We also thank the Collège québécois des médecins de famille, the Collège des médecins de famille du Québec and the Collège des médecins du Québec for their initiative in developing the workshop. Finally, we thank workshop leaders Drs. Raymond Lalande, Johanne Blais and Roger Ladouceur, the standardized patients and the physicians who participated in the study.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Marie-Dominique Beaulieu was the principal author and was involved in all aspects of the study. Marie-Dominique Beaulieu and Claude Beaudoin were the study's principal investigators. All the authors were involved in planning the study and writing the protocol. Eveline Hudon, Claude Beaudoin (who died before this article was written) and Martine Remondin were involved in the data collection. Michèle Rivard was responsible for data analysis with Marie- Dominique Beaulieu. All the authors were involved in interpreting the data, and all but Claude Beaudoin reviewed the first draft of the article and participated in subsequent revisions.

This study was made possible by a grant from the Medical Research Council of Canada (MRC) and Aventis Pharma through the MRC–Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association of Canada.

We also received funding from Health Canada and from the College of Family Physicians of Canada for development of the workshop and production of materials given to the participants.

Competing interests: Marie-Dominique Beaulieu, Danielle Saucier and Martine Remondin received financial support from Aventis Pharma Inc., Laval, Que., to attend conferences where preliminary results of the study were presented. Marie-Dominique Beaulieu and Danielle Saucier received an honorarium from the Collège des médecins du Québec for their role as workshop leaders (as did all the other workshop leaders).

Correspondence to: Dr Marie-Dominique Beaulieu, Chaire Dr Sadok Besrour en médecine familiale, Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal, Hôpital Notre-Dame, Pavillon L.-C. Simard, 8e étage, 1560, rue Sherbrooke Est, Montréal QC H2L 4M1; fax 514 412-7579; maried.beaulieu@sympatico.ca

References

- 1.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Effective dissemination and implementation of Canadian Task Force guidelines on preventive health care: literature review and model development. Ottawa: Health Canada; 1999. Available (PDF format): www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hppb/healthcare/pubs/ctfguidelines/pdf/edctfg.pdf (accessed 2002 August 22).

- 2.Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A. Translating guidelines into practice. CMAJ 1997;157:408-16. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Wensing M, Van Der Weijden T, Grol R. Implementing guidelines and innovation in general practice: Which interventions are effective? Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:991-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB. Changing physician performance. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA 1995;274:700-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Thomson O'Brien MA, Freemantle N, Oxman AD, Wolf F, Davis DA, Herrin J. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes [Cochrane review]. In: The Cochrane Library; Issue 4, 2001. Oxford: Update Software. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.L'examen médical périodique. Atelier sur les applications quotidiennes des recommandations les plus récentes en matière de prévention clinique auprès des adultes. Montréal: Collège des médecins du Québec; 1998.

- 7.Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. The Canadian guide to clinical preventive health care. 1st ed. Ottawa: Canada Communication Group; 1994.

- 8.Tamblyn R, Battista RN. Changing clinical practice: Which intervention works? J Contin Educ Health Prof 1993;13:273-88.

- 9.Beaulieu MD, Hudon E, Roberge D, Pineault R, Forté DLJ. Practice guidelines on clinical prevention: Do patients, physicians and experts share common ground? CMAJ 1999;161:519-23. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Hutchison B, Woodward CA, Norman GR, Abelson J, Brown JA. Provision of preventive care to unannounced standardized patients: correlates of family physician performance. CMAJ 1998;158:185-93. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Tamblyn RM, Klass DJ, Schnabl GK, Kopelow ML. The accuracy of standardized patient presentations. Med Educ 1991;25:100-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Tamblyn RM. Use of standardized patients in the assessment of medical practice. CMAJ 1998;158:205-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Brown JA, Abelson J, Woodward CA, Hutchison B, Norman G. Fielding standardized patients in primary care settings: lessons from a study using unannounced standardized patients to assess preventive care practices. Int J Qual Health Care 1998;10:199-206. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Fleiss JL. The measurement of interrater agreement. In: Fleiss JL, editor. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1981. p. 211-36.

- 15.Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism: the CAGE Questionnaire. JAMA 1984;252:1905-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Lignes directrices de pratique clinique pour le traitement du diabète au Canada. CMAJ 1998;159(8 Suppl).

- 17.Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Harvey E, Oxman AD, Thomson MA. Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. BMJ 1998;317:465-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]