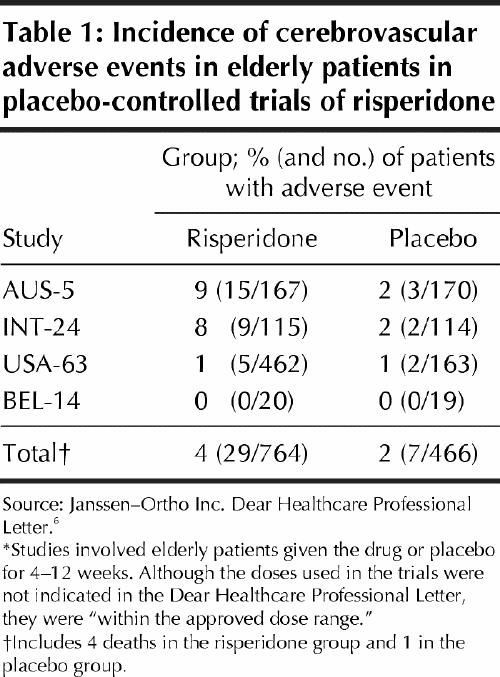

Reason for posting: The burden of dementia is staggering — over 8% of the population over the age of 65 is affected1 — and behavioural disturbances that often accompany dementia (including physical aggression, hallucinations, wandering, yelling, throwing and vocalizations)2 are distressing for caregivers and patients alike.3 Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors may play a role in slowing the cognitive decline of patients with Alzheimer's disease,4 but low-dose therapy with antipsychotic agents (including risperidone) is often used to control behavioural problems.5 However, a recent analysis by the drug's manufacturer of trials involving patients with dementia suggests that the use of risperidone may be associated with increased rates of cerebrovascular adverse events, including stroke and transient ischemic attacks, when compared with placebo.6 In 4 placebo-controlled trials lasting 1–3 months and involving more than 1200 patients with Alzheimer's disease or vascular dementia, cerebrovascular adverse events were twice as common in the risperidone-treated group (4%) as in the placebo group (4% v. 2%) (Table 1). A further search of international databases of postmarketing adverse events revealed 37 cases (1 in Canada) of such events in elderly dementia patients taking risperidone, of which 16 (43%) were fatal.6

Table 1

The drug: Although the exact mechanism of action of risperidone is unknown, the drug blocks receptors in the dopaminergic, adrenergic and histaminergic neurotransmitter systems as well as those in the serotonin system that may play a role in agression.7,8,9 Like other atypical antipsychotic agents, risperidone is a popular first-line agent for psychotic disorders because it is effective (especially for negative symptoms) and is associated with fewer extrapyramidal adverse effects than are traditional antipsychotic drugs.7 Risperidone, at doses higher than those used in dementia, appears to cause diabetes, worsened lipid profiles and obesity in some patients,10 but any relation between these adverse effects and risperidone-associated cerebrovascular adverse events is unclear. Risperidone should be used with caution in patients with seizure disorders and avoided in states of dehydration and hypotension.

What to do: Dementia is a difficult burden for patients and caregivers,11 but the degree to which a behaviour is a problem depends greatly on a caregiver's ability to tolerate the problem. Given dementia's prevalence and its sufferer's susceptibility to medication-related adverse events, nonpharmacologic measures are often preferable. Education of family members about natural exacerbations of disruptive behaviours in the early evening (“sun-downing”) is important, and the “knee-jerk” initiation of pharmacologic measures should be avoided. An assessment for alternative causes of disruptive behaviour (e.g., delirium) may be warranted in some patients. Family members caring for affected patients at home are often reluctant to seek extra help,11 and physicians are often key to providing emotional and practical support for applications for increased home care or eventual placement in long-term care facilities. Such facilities often offer special floors for patients with dementia-related behavioural problems and have staff available around the clock who are acquainted with and tolerant of such problems and who can offer close supervision and frequent reassurance of patients (often minimizing violent outbursts). Locked and alarmed floors and registration with an Alzheimer's “wandering registry” (www.alzheimer.ca) are further nonpharmacologic harm-reduction strategies.

If medications are indicated, decision-makers should be informed of the possible risks, and low doses (e.g., risperidone 0.25 mg twice daily)8 should be used. Risperidone should be used with caution in patients with cardiovascular disease (including heart failure, myocardial infarction or ischemia, cerebrovascular disease, or conduction abnormalities). Patients should be monitored for excessive sedation, hypotension (especially if taking antihypertensive agents), extrapyramidal side effects, neuroleptic malignant syndrome and cerebrovascular adverse events. The relative cardiovascular safety of alternative antipsychotic agents (haloperidol, olanzapine, clozapine or quetiapine) is currently unknown.

Eric Wooltorton CMAJ

References

- 1.Canadian Study of Health and Aging Working Group. Canadian Study of Health and Aging: study methods of prevalence of dementia. CMAJ 1994;150:899-913. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Beers MH. Behavior disorders in dementia. In: The Merck manual of geriatrics. Whitehouse Station (NJ): Merck & Co. Inc.; 2000. p. 371-7.

- 3.Ballard C, O'Brien J. Treating behavioural disease and psychological signs in Alzheimer's disease. BMJ 1999;319:138-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Gauthier S. Advances in the pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer's disease. CMAJ 2002;166(5):616-23. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Tune LE. Risperidone for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(Suppl 21):29-32. [PubMed]

- 6.Risperdal (risperidone) and cerebrovascular adverse events in placebo-controlled dementia trials [Dear Healthcare Professional Letter]. Toronto: Janssen–Ortho Inc.; 2002 Oct 11. Available: www .hc-sc.gc.ca/hpb-dgps/therapeut/zfiles/english /advisory /industry/risperdal1_e.pdf (accessed 2002 Oct 25).

- 7.Edwards JG. Risperidone for schizophrenia. BMJ 1994;308:1311-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Risperidol (risperidone) [product monograph]. In: Compendium of pharmaceuticals and specialties. Ottawa: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2002. p. 1486-90.

- 9.Mintzer JE. Underlying mechanisms of psychosis and aggression in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(Suppl 21):23-5. [PubMed]

- 10.McIntyre RS, McCann SM, Kennedy SH. Antipsychotic metabolic effects: weight gain, diabetes mellitus and lipid abnormalities. Can J Psychiatry 2001;46(3):273-81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Grunfeld E, Glossop R, McDowell I, Danbrook C. Caring for elderly people at home: the consequences to caregivers. CMAJ 1997;157(8):1101-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]