Abstract

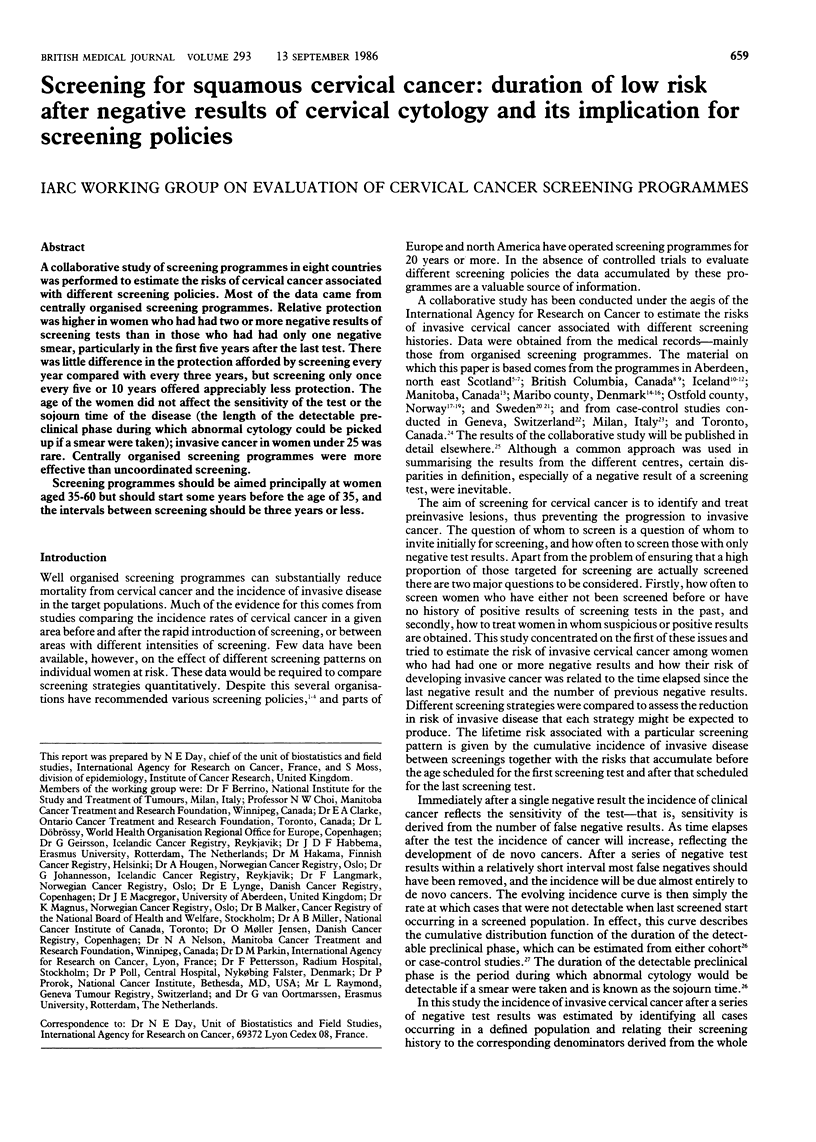

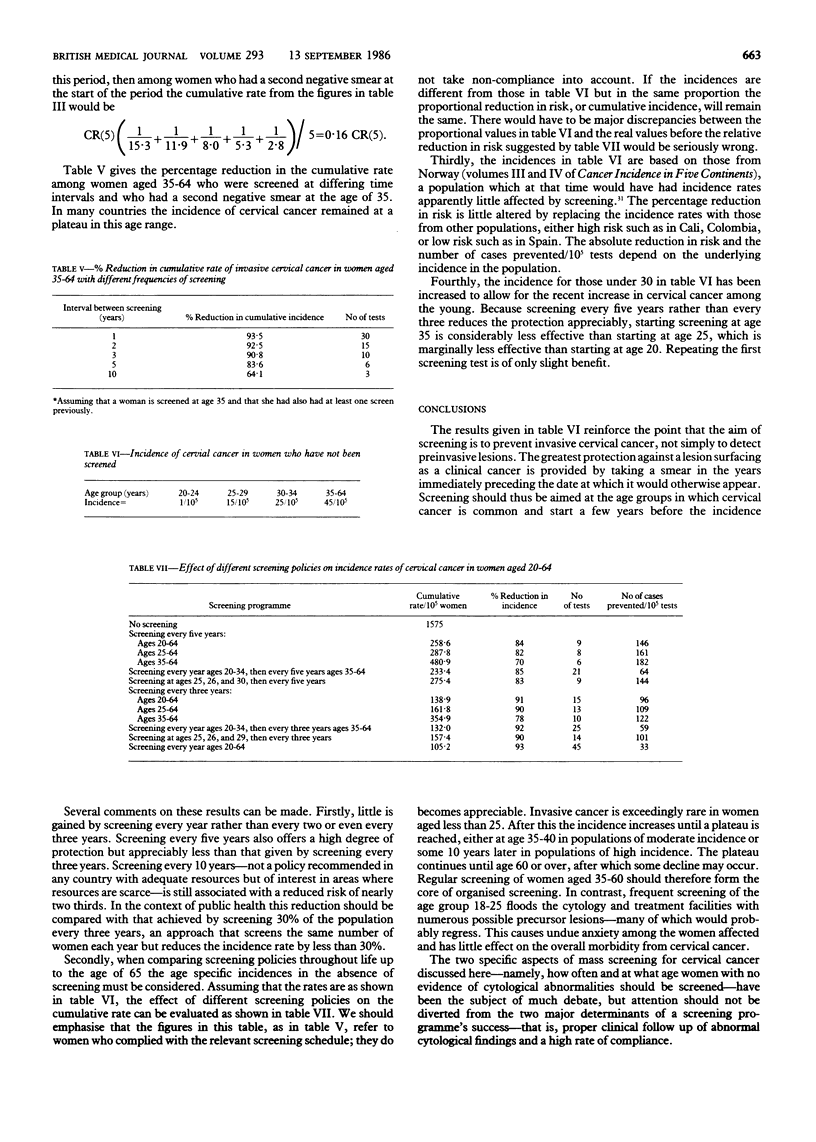

A collaborative study of screening programmes in eight countries was performed to estimate the risks of cervical cancer associated with different screening policies. Most of the data came from centrally organised screening programmes. Relative protection was higher in women who had had two or more negative results of screening tests than in those who had had only one negative smear, particularly in the first five years after the last test. There was little difference in the protection afforded by screening every year compared with every three years, but screening only once every five or 10 years offered appreciably less protection. The age of the women did not affect the sensitivity of the test or the sojourn time of the disease (the length of the detectable preclinical phase during which abnormal cytology could be picked up if a smear were taken); invasive cancer in women under 25 was rare. Centrally organised screening programmes were more effective than uncoordinated screening. Screening programmes should be aimed principally at women aged 35-60 but should start some years before the age of 35, and the intervals between screening should be three years or less.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Berget A. Influence of population screening on morbidity and mortality of cancer of the uterine cervix in Maribo Amt. Dan Med Bull. 1979 Apr;26(2):91–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyes D. A., Morrison B., Knox E. G., Draper G. J., Miller A. B. A cohort study of cervical cancer screening in British Columbia. Clin Invest Med. 1982;5(1):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day N. E., Walter S. D. Simplified models of screening for chronic disease: estimation procedures from mass screening programmes. Biometrics. 1984 Mar;40(1):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler H. K., Boyes D. A., Worth A. J. Cervical cancer detection in British Columbia. A progress report. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1968 Apr;75(4):392–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1968.tb00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesson G., Geirsson G., Day N., Tulinius H. Screening for cancer of the uterine cervix in Iceland 1965--1978. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1982;61(3):199–203. doi: 10.3109/00016348209156556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macgregor J. E., Moss S. M., Parkin D. M., Day N. E. A case-control study of cervical cancer screening in north east Scotland. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985 May 25;290(6481):1543–1546. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6481.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond L., Obradovic M., Riotton G. Une étude cas-témoins pour l'évaluation du dépistage cytologique du cancer du col utérin. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 1984;32(1):10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenkvist B., Bergström R., Eklund G., Fox C. H. Papanicolaou smear screening and cervical cancer. What can you expect? JAMA. 1984 Sep 21;252(11):1423–1426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]