Abstract

Mammalian heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K (hnRNP K) is an RNA- and DNA-binding protein implicated in the regulation of gene expression processes. To better understand its function, we studied two Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologues of the human hnRNP K, PBP2 and HEK2 (heterogeneous nuclear RNP K-like gene). pbp2Δ and hek2Δ mutations inhibited expression of a marker gene that was inserted near telomere but not at internal chromosomal locations. The telomere proximal to the ectopic marker gene became longer, while most of the other telomeres were not altered in the double mutant cells. We provide evidence that telomere elongation might be the primary event that causes enhanced silencing of an adjacent reporter gene. The telomere lengthening could, in part, be explained by the inhibitory effect of hek2Δ mutation on the telomeric rapid deletion pathway. Hek2p was detected in a complex with chromosome regions proximal to the affected telomere, suggesting a direct involvement of this protein in telomere maintenance. These results identify a role for hnRNP K-like genes in the structural and functional organization of telomeric chromatin in yeast.

Heterogeneous nuclear RNPs (hnRNPs) bind to primary transcripts in the nucleus and along with small RNA ribonucleoprotein complexes mediate RNA maturation and transport to the cytoplasm (5). Much progress has been made in the identification and elucidation function of these components. It is becoming clear that hnRNPs have a broader role than was previously thought. For instance, yeast Rlf6p and the mammalian A1 hnRNPs were shown to directly bind telomeric DNA sequences and alter the metabolism of telomeres (21, 23). Mammalian hnRNP K was shown to bind CT-rich elements within several promoters and to modulate transcription (39). Drosophila DDP1, a single-stranded nucleic acid-binding protein containing K homology (KH) domains, binds pericentric heterochromatin and controls cell ploidy (8). These data imply that hnRNP K and other RNA-binding proteins are able to bind and regulate both DNA- and RNA-dependent processes.

K protein contains three evolutionarily conserved KH domains; similar domains were also found in RNA- and DNA-binding proteins derived from organisms as diverse as Escherichia coli and mammals (54). The structure of the K protein KH3 domain has recently been determined (2). It contains a three-stranded β-sheet stacked against three α-helices, βααββα, a structural fold found in other RNA-binding proteins unrelated to K protein in primary sequence (5). K protein contains a cluster of three proline-rich SH3-binding segments (16, 57, 59) that reside within the K-interactive domain (3). The K-interactive domain mediates the interaction of K protein with a number of its protein partners (6, 12, 18, 39, 47, 59). K protein also contains both the nuclear localization signal and nuclear shuttling domain (38). A general model is emerging where K protein may serve to link signal transduction pathways to nucleic acid-directed processes (42).

We have recently shown that the mammalian K protein interacts with the Polycomb Group protein Eed (11). K protein also binds DNA-methyltransferase (50). Involvement of these K protein partners in chromatin rearrangements suggested a role for K protein in chromatin function. Consistent with this notion is the observation that K protein binds telomeric repeat DNA in vitro (24). Here we identified two Saccharomyces cerevisiae hnRNP K-like proteins, Pbp2p (Hek1p) and Hek2p, as suppressors of the telomeric position effect (TPE). Our data provide evidence for a direct role of these genes in chromatin-dependent processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, plasmids, and methods.

Media used for the growth of S. cerevisiae were as previously described (13); cells were grown at 30°C. All strains used in this study (Table 1) except UCC3505, UCC3515, and AYH2.45 were isogenic with YPH250 (51). Yeast transformation was performed by the lithium acetate procedure as described in Technical Tips Online (http://tto.trends.com). 5-Fluoroorotic acid resistance (5-FOAR) was determined as described in reference 1. 5-FOAR was obtained from Zymo Research (Orange, Calif.). PCR-mediated gene disruption was performed as described in reference 4.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Reference or origin |

|---|---|---|

| YPH250 | MATaade2-101 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 lys2-801 trp1-Δ1 ura3-52 | 51 |

| UCC509 | YPH250 DIU5-11 | 44 |

| UCC511 | YPH250 DIU5-13 | 44 |

| UCC513 | YPH250 DIU5-3 ppr1::HIS3 | 44 |

| UCC519 | YPH250 DIU5-9 ppr1::HIS3 | 44 |

| UCC521 | YPH250 DIU5-11 ppr1::HIS3 | 44 |

| UCC523 | YPH250 DIU5-13 ppr1::HIS3 | 44 |

| UCC3505 | MATaura3-52 lys2-801 ade2-101 trp1-Δ63 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 ppr1::HIS3 adh4::URA TEL DIA5-1 | 52 |

| DY14 | UCC509 pbp2::TRP1 | This study |

| DY15 | UCC509 hek2::HIS3 | This study |

| DY16 | UCC509 pbp2::TRP1 hek2::HIS3 | This study |

| DY22 | UCC513 hek2::TRP1 | This study |

| DY25 | UCC519 pbp2::LEU2 hek2::TRP1 | This study |

| DY28 | UCC3505 pbp2::LEU2 hek2::TRP1 | This study |

| UCC3515 | MATα ade2-101 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 lys2-801 trp1-Δ63 ura3-52::hml::URA3 | 53 |

| UCC4565 | UCC3515 ppr1::LYS2 | 53 |

| DY115 | UCC3515 pbp2::TRP1 | This study |

| DY116 | UCC3515 hek2::HIS3 | This study |

| DY117 | UCC3515 pbp2::TRP1 hek2::HIS3 | This study |

| DY1000 | UCC509 rad52::kanMX6 | This study |

| DY119 | UCC509 HEK2-3HA:kanMX6 | This study |

| DY122 | UCC509 HEK2-3HA:kanMX6 sir3::HIS3 | This study |

| AYH2.45 | MATaade2-101 his3-Δ200 leu2-3,-112 lys2-801 trp1-Δ901 ura adh4::URA3TelVII-L sir3::SIR3HA/HIS3 | 56 |

The BamHI-MspA1I fragment of the pHR67-23 plasmid (44) containing the SIR3 gene with the upstream putative regulatory elements was cloned into a BamHI-Ecl136II-cut derivative of the pVP16 plasmid (2μm LEU2) (61) from which the ADH promoter and VP16 open reading frame (ORF) were deleted (SphI fragment). The final plasmid pSIR3 was used to overexpress SIR3 in yeast strains.

Northern, Southern, and Western blot analysis.

RNA was purified from mid-log-phase yeast cultures (5 ml) as described in reference 46. RNA samples were analyzed as described previously (12). After first being denatured in a buffer containing formamide at 65°C for 15 min, the RNA samples were cooled on ice. Five micrograms of the total RNA per lane was resolved by electrophoresis in a 1.2% agarose gel containing 2.2 M formaldehyde. RNA then was transferred to a Nytran membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.) and UV irradiated. The membranes were prehybridized for 2 h at 42°C in prehybridization buffer (50% formamide, 5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate] 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 0.1 mg of denatured salmon sperm DNA/ml, and 0.1 mg of E. coli tRNA/ml). After prehybridization, 32P-labeled cDNA probe (2 × 106 cpm/ml) was added and hybridization was carried out overnight at 42°C. Following hybridization, the membranes were washed twice in 2× SSC with 0.1% SDS at 22°C for 10 min, washed twice in 0.1× SSC with 0.1% SDS at 50°C for 30 min, and exposed to X-ray film.

DNA from yeast cells was purified by the phenol/glass bead method as described in reference 17. Cells from 2-ml overnight cultures were collected by centrifugation, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept at −70°C. After two rounds of phenol deproteinization, nucleic acids were precipitated with ethanol, collected by centrifugation, and dissolved in 100 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer. The samples were treated with RNase A (100 μg/ml, 20 min at 37°C) and then extracted with phenol/chloroform, precipitated with 3 volumes of ethanol, washed once with 70% ethanol, air dried, and dissolved in 50 μl of water. One or two micrograms of DNA was used for Southern blot analysis. DNA samples were resolved in a 1% agarose gel (Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer), and after electrophoresis nucleic acids were transferred from the gel onto a Nytran membrane (Schleicher & Schuell). Prehybridization and hybridization conditions were identical to those described in the Northern blot analysis protocol.

The following DNA fragments were used as probes: (i) URA3, a PstI-NaeI fragment of the URA3 gene that was excised from pRS306. (ii) Y′, a fragment of the Y′ subtelomeric element neighboring the conserved XhoI site at the end of the element, was amplified by PCR. The primers were designed to the regions located 390 bp upstream (forward primer) and 360 bp downstream (reverse primer) of the XhoI site. (iii) ACT1 ORF was amplified by PCR. (iv) VR, a fragment of the VR chromosomal end neighboring the EcoRI site located upstream of the Y′ element, was amplified by PCR. The primers were designed to the regions with coordinates 567023 (forward) and 567576 (reverse) on chromosome V. PCR products were used directly as probes. (v) The EcoRI-BamHI fragment of pYTCA-2 (13) containing the TG1-3 repeat was used as a probe for telomeric repeat sequences.

Western blot analyses with antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) monoclonal antibody (12CA5; Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) were performed as described elsewhere (56).

Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR).

RNA samples were treated with RNase-free DNase I (1 U/10 μg of RNA; Epicentre Technologies, Madison, Wis.) for 15 min at 37°C and then phenol deproteinized. One microgram of DNA-free RNA was reverse transcribed by SuperscriptII (200 U; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) with a random hexanucleotide mixture (1 μM) for 1 h at 42°C. One-tenth of the reaction mixture was then amplified by PCR with the following sets of primers: (i) primers specific to the beginning and end of ACT1 or URA3 ORFs and (ii) primers specific to the regions with coordinates 567023 (forward) and 567576 (reverse) on chromosome V. PCR was performed in a 25-μl final volume with 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Gibco BRL) for 30 to 32 cycles. Five microliters of the reaction mixtures was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Immunoprecipitation of HA-tagged Hek proteins from fixed whole-cell extracts and PCR analysis of precipitated DNA.

The pFA6a-3HA-kanMX6 plasmid was used to insert the 3HA-kanMX6 cassette into HEK2 between the last codon and stop codon of the ORF as described in reference 29. Modified strains were tested by genomic PCR and Western blot analysis of cellular proteins with anti-HA monoclonal antibody (12CA5; Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Formaldehyde cross-linking, whole-cell extract preparation, immunoprecipitation, DNA purification, and PCR analysis were performed as described in reference 56. Sonication treatment resulted in an average DNA fragment size of 0.5 to 1 kb. PCRs (30 cycles) were carried out in a 25-μl volume with 1/100 of the immunoprecipitated material and 1/18,000 of the input material. PCR products were separated on 1% agarose gels and visualized with 0.1 μg of ethidium bromide/ml.

RESULTS

Yeast homologues of mammalian hnRNP K.

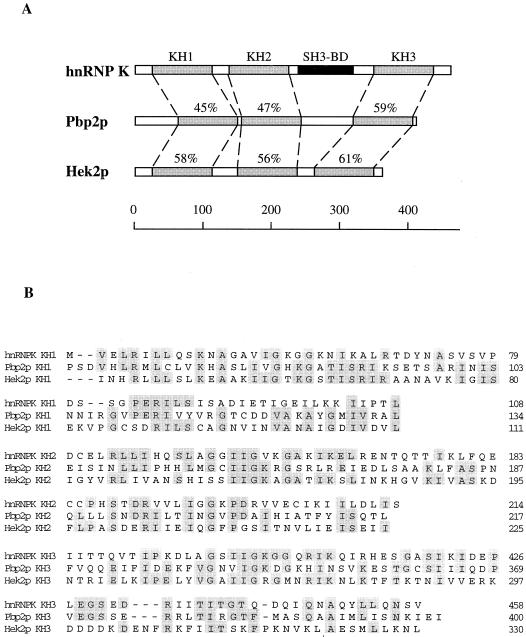

Blast search analysis of the S. cerevisiae genome revealed two ORFs similar to the mammalian K protein, YBR233w and YBL032w. Like K protein, each of the deduced yeast proteins contains three KH domains that appear as the most conserved regions of the yeast and mammalian proteins (Fig. 1A and B). We have also found other KH-containing proteins, but those proteins shared much lower similarity with the mammalian K protein. We have designated the YBR233w ORF as HEK1 (heterogeneous nuclear RNP K-like gene) and the YBL032w ORF as HEK2. The HEK1 gene was recently isolated as one of the clones, PBP2, interacting in a two-hybrid screen with yeast poly(A)-binding protein (34). PBP2 was also described as a gene conferring resistance to the antimalaria drug mefloquine in yeast (10). In this assay, mammalian hnRNP K can fully replace the PBP2 function, providing evidence that the yeast and mammalian proteins are functional homologues (10). Until now no functional studies of the HEK2 gene have been described.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the human K protein and the yeast homologues Pbp2p and Hek2p. (A) Similarity between the deduced amino acid sequences of the human hnRNP K protein and S. cerevisiae Pbp2p (YBR233w) and Hek2p (YBL032w). KH1 to -3, KH domains (percentage of similarity is shown); and SH3-BD, SH3-binding domain. The scale depicts length in amino acid residues. (B) results of KH domain alignment. Identical positions are shaded. (C) Murine K protein and yeast PBP2 and HEK2 cDNAs were transcribed and translated in vitro. 35S-labeled Pbp2p and Hek2p translational products were analyzed by SDS-electrophoresis and autoradiography. (D) RNA- and protein-binding specificity of K protein, Pbp2p, and Hek2p. 35S-labeled translational products were incubated with agarose beads bearing different homopolynucleotides in a buffer containing 150 mM KCl. After incubation the beads were washed with the same buffer, and bound proteins were eluted with SDS sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. Load, 20% of the sample used in the binding reaction.

The PBP2 and HEK2 genes were cloned and transcribed and translated in a cell-free system (Fig. 1C). Both of the cDNAs gave a single translational product of the predicted size. K protein binds avidly to poly(C) RNA, in contrast to most other cellular RNA-binding proteins, which prefer poly(U) (36, 37). Therefore, we compared the RNA-binding specificity of the murine K and yeast Hek proteins (Fig. 1D). K protein binds poly(C) and poly(U) but does not bind poly(A). Both Pbp2p and Hek2p bind poly(C) and poly(U) well, which is consistent with the sequence analysis evidence that these yeast proteins are homologues of K protein. To define the function of K-like proteins in yeast, we generated single (pbp2Δ and hek2Δ) and double (pbp2Δ hek2Δ) mutants. These strains were viable and had the same growth rates as the parental wild-type strains, and the pattern of 35S pulse-labeled cellular proteins observed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis was not detectably altered by the mutations (not shown). These results show that PBP2 and HEK2 are nonessential genes under the conditions used.

PBP2 and HEK2 act as modifiers of TPE.

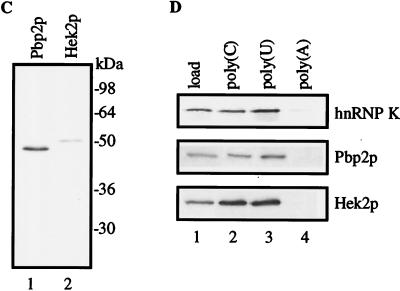

Recently we identified the Polycomb group protein Eed as one of the partners of the mammalian K protein (11). This finding suggested a direct role for K protein in chromatin-dependent processes. We wondered if Pbp2/Hek2 proteins could play such a role. To test this possibility we examined the effect of PBP2 and HEK2 disruption on TPE, a well-described reporter system for studying chromatin-mediated processes in yeast (13). This system is based on the finding that a marker gene placed near the telomere is a subject of heritable silencing. In the first experiment we used a strain where URA3 was introduced to the end of chromosome VR (44) (Fig. 2A). Disruption of both PBP2 and HEK2 resulted in a substantial increase in the fraction of cells with repressed URA3, compared to the wild-type strain, the amount of which was measured by counting 5-FOAR cells present in exponentially growing cultures. Double mutation (pbp2Δ hek2Δ) further increased the percentage of 5-FOAR cells. Thus, these mutations enhance TPE. A similar effect of pbp2Δ hek2Δ mutation on TPE was observed in a strain where URA3 was introduced to the end of chromosome VIIL (not shown), indicating that this effect is not chromosome specific. To exclude the possibility that these effects were specific to the URA3 gene, we next tested another strain where the ADE2 gene was introduced to the end of chromosome VR (52). The wild-type strain colonies have several white (ade+) and fewer pink (ade−) sectors, while the pbp2Δ hek2Δ colonies have more red than white sectors (Fig. 2B). This result shows that the pbp2Δ hek2Δ mutation enhances repression of subtelomeric ADE2, indicating that the observed effects of PBP2 and HEK2 deletion on TPE are not specific to one marker gene.

FIG. 2.

Enhanced TPE in pbp2Δ hek2Δ strains. (A) PBP2 HEK2 (UCC509 [44]), pbp2Δ (DY14), hek2Δ (DY15), and pbp2Δ hek2Δ (DY16) strains were grown on yeast-peptone-dextrose agar plates for 2 days; separate colonies were grown in yeast-peptone-dextrose liquid medium. Tenfold serial dilutions of overnight cultures were plated on either complete or 5-FOA-supplemented agar media. The graph represents the fraction of cells forming colonies on 5-FOA medium compared with cells forming colonies on nonselective medium, from at least four independent experiments. (B) Subtelomeric ADE2 gene expression in PBP2 HEK2 and pbp2Δ hek2Δ strains. Wild-type (PBP2 HEK2, strain UCC3505) and mutant (pbp2Δ hek2Δ, strain DY28) cells with the ADE2 gene introduced near the VR telomere (52) were grown on yeast-peptone-dextrose agar for 3 days at 30°C, and then the dish was kept at 4°C for 1 week to develop the color. (C) Growth of wild-type and hek mutant strains containing URA3 inserted into the HML locus on media either lacking uracil or containing 5-FOA. Tenfold dilutions of wild-type (WT; strain UCC3515 [53]), pbp2Δ (strain DY115), hek2Δ (strain DY116), pbp2Δ hek2Δ (strain DY117), and ppr1Δ (strain UCC4565) strains were spotted onto complete medium (Complete), medium lacking uracil (−URA), or medium containing 5-FOA. The experiment was repeated three times, and the results of one representative experiment are shown. (D) Level of URA3 mRNA expression in pbp2Δ hek2Δ strains. Individual colonies were grown to mid-log phase in yeast-peptone-dextrose, cells were harvested by centrifugation, and total RNA was extracted by the phenol/glass bead method. RNA samples (5 μg each) were examined by Northern blot analysis with fragments of URA3 (upper panel) or ACT1 (lower panel) genes used as probes. The position of URA3, ura3-52, and ACT1 transcripts is shown. Strains used: 1 to 3, UCC509 (PBP2 HEK2); 4 to 6, DY16 (pbp2Δ hek2Δ); 7, UCC511 (PBP2 HEK2 [44]); 8, DY19 (pbp2Δ hek2Δ); and 9, YPH250 (PBP2 HEK2). Numbers above the panels represent frequencies of 5-FOA-resistant cells. N/A, not applicable. The chromosomal constructs used in these experiments are shown below.

Next we tested the effect of pbp2Δ and hek2Δ mutations on silencing of the URA3 gene inserted at the HML locus. The fractions of cells surviving on uracil-lacking media or 5-FOA-supplemented media were similar for the wild-type and hek mutant strains (Fig. 2C). In contrast to pbp2Δ and hek2Δ mutations, deletion of the PPR1 transcription factor for the URA3 gene (ppr1Δ mutation) substantially decreased growth of these cells on uracil-lacking medium, indicating that silencing of the hml::URA3 construct was increased (Fig. 2C; see also reference 53). We similarly found no effect of hek mutations on URA3 gene expression at the HMR locus (data not shown). To increase the sensitivity of this assay, we performed experiments employing 6-azauracil (6-AU), a competitive inhibitor of the URA3-encoded enzyme orotidine 5′-phosphate decarboxylase (28, 53). Likewise, these experiments revealed no difference between the wild-type and hek mutant strains in the growth rates on uracil-lacking media supplemented with 6-azauracil (data not shown). In agreement with these results, hek mutations had no effect on the mating efficiency of these strains (data not shown). Thus, unlike the enhanced TPE observed in hek mutants, there were no changes in silencing of the mating loci.

To discriminate between transcriptional and translational effects, the level of URA3 mRNA was measured in these strains. The results of Northern blot analysis are shown in Fig. 2D. The level of URA3 mRNA was substantially decreased in the mutant pbp2Δ hek2Δ strain, compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 2D, compare lanes 4 to 6 and 1 to 3). Expression of the URA3 gene that was localized farther from the telomere (Fig. 2D, lanes 7 and 8) and expression of the internal ura3-52 gene were changed little in the mutant strains. These data suggest that PBP2/HEK2 genes modulate URA3 transcription, a process that depends on the chromosomal location of the URA3 gene. Alternatively, Pbp2 and Hek2 proteins could modulate the stability of URA3 mRNA, depending on the position of this gene within the genome, but this possibility is less likely.

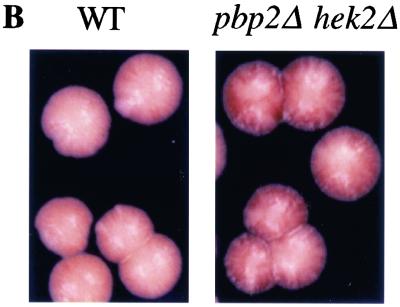

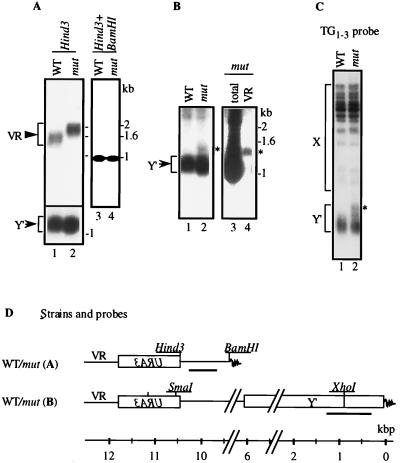

The effect of pbp2Δ hek2Δ mutation on the length of telomeres.

In S. cerevisiae, telomeres contain ∼350 bp of (TG1–3)n (49, 62). Some mutations of genes that modify TPE also alter the length of telomeres (14, 30, 63), implying that components of telomeric chromatin are involved in the maintenance of chromosomal ends. Therefore, we measured the length of telomeres in our strains. The pbp2Δ hek2Δ mutation resulted in a substantial increase in the length of the telomere neighboring the URA3 gene (Fig. 3A, lanes 1 and 2, and B, lanes 1 to 4). This increase was not dependent on the chromosomal end bearing URA3 (not shown) or the presence or absence of the natural subtelomeric sequences, such as Y′ and X boxes (Fig. 3A and B). The observed telomere extension resulted from the addition of DNA fragments to the TG1-3 repeat region, as digestion with HindIII-BamHI showed the unchanged size of the DNA fragment adjacent to the telomere in the öhek mutant strain compared to in the wild-type strain (Fig. 3A, compare lane 3 to lane 4). In telomerase and some SIR3/histone H4 mutant strains, fragments of the Y′ box (5.5 to 6.7 kb) are frequently inserted into the telomere region and may cause lengthening of the nearby TG1-3 repeat region (32, 33, 60). Thus, we wondered if the Y′ box or its fragment was inserted to the URA3-modified telomere in pbp2Δ hek2Δ mutants. This possibility was ruled out by the results of Southern blot analysis of this region with URA3-, VR-, Y′-, and TG1-3-specific probes (Fig. 3 and results not shown). To test if other telomeres were altered in the pbp2Δ hek2Δ mutants, we used a fragment of the Y′ box and TG1-3 repeat as probes in Southern blots. Interestingly, unlike what was found for the VR telomere, little or no change was found in the length of other telomeres (Fig. 3A, lower panel, B, and C). Thus, in contrast to other known TPE modifiers that alter the length of most telomeres (30), the pbp2Δ hek2Δ mutation specifically elongates the telomere adjacent to the inserted URA3 gene.

FIG. 3.

The effect of PBP2 and HEK2 disruption on the length of telomeres. (A) UCC519 (PBP2 HEK2 [44]) and DY25 (pbp2Δ hek2Δ) strains were grown on yeast-peptone-dextrose agar media; separate colonies were grown overnight in the same liquid media. Cells were collected by centrifugation; DNA was extracted by the phenol/glass bead method (Materials and Methods). One microgram of DNA was digested with either HindIII (upper panel, lanes 1 and 2), HindIII and BamHI (lanes 3 and 4), or XhoI (lower panel, lanes 1 and 2). The products were analyzed by the Southern method with either VR (upper panel, lanes 1 through 4) or Y′ (lower panel, lanes 1 and 2) probes. Arrowhead and arrow mark the position of DNA fragments bearing the telomeric repeat either proximal to the URA3 gene (VR) or corresponding to the Y′-type chromosomal ends (Y′) respectively. WT, wild type; mut, mutant. (B) UCC513 (PBP2 HEK2 [44]) and DY22 (PBP2 hek2Δ) strains were grown and analyzed as described for panel A. DNA was digested with XhoI (lanes 1 and 2) and was analyzed by the Southern method with the Y′ probe. For lanes 3 and 4, genomic DNA was cut with SmaI (this site is introduced with URA3 to VR. The arrowhead marks DNA fragment corresponding to Y′ probe. All other chromosomal ends recognized by the Y′ probe do not contain a SmaI site within 25 kb adjacent to telomeres); the 11-kb zone was purified from gel, cut with XhoI, and then analyzed by the Southern method with the Y′ probe. WT, PBP2 HEK2 cells; mut, PBP2 hek2Δ cells; asterisk, position of DNA fragment specific to the sample purified from hek2Δ cells. (C) DNA samples shown in panel B, lanes 1 and 2, were cut with XhoI and analyzed by Southern blotting with a probe specific to the TG1-3 repeat. Position of fragments corresponding to the X- and Y′-type chromosomal ends is marked. The asterisk indicates the position of DNA fragment specific to the sample purified from hek2Δ (mut) cells. (D) Chromosomal constructs and probes (bold lines) used to measure telomere length. The diffuse dark end represents the telomeric (TG1-3)n repeat and is not drawn to scale.

Forced transcription through the telomeric TG1–3 repeat region decreases its length (45). It is therefore possible that a similar phenomenon could account for the single telomere lengthening in pbp2Δ hek2Δ mutant cells. For example, in the wild-type strains, there could be transcription through the TG1–3 repeat region initiated at the ectopic URA3 gene. If so, decreased URA3 transcription in pbp2Δ hek2Δ strains (Fig. 2D) could result in a longer telomere. To test this possibility, we searched for a transcript corresponding to the DNA region localized between the URA3 gene and TG1-3 telomeric repeat. When either RT-PCR (Fig. 4) or Northern blot analysis (not shown) was used, no such transcript was detected. These results suggest that there was no detectable transcription through the telomere initiated by the ectopic URA3.

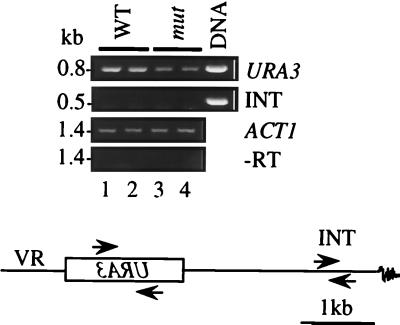

FIG. 4.

RT-PCR analysis of transcription of the subtelomeric region in pbp2Δ hek2Δ cells. After DNase treatment, RNA samples (1 μg each, same as shown in Fig. 2D) were reverse transcribed with random hexanucleotide mixture as a primer and then amplified by PCR with primers specific to ACT1, URA3, and the chromosomal region localized between the URA3 gene and the neighboring TG1-3 repeat (INT). −RT, no RT added, DNA, 1 μg of total DNA was used as a template in PCR. Strains used: 1 and 2, UCC509 (WT, PBP2 HEK2); and 3 and 4, DY16 (mut, pbp2Δ hek2Δ).

Lengthening of a telomere is associated with enhanced TPE in cis.

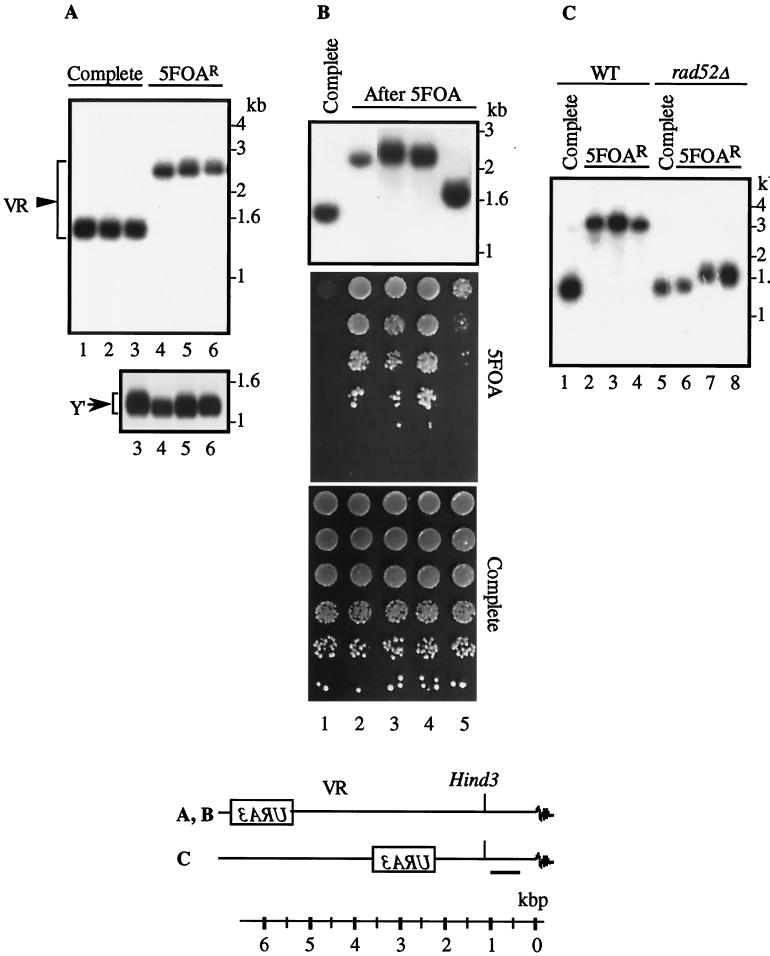

The telomeric TG1-3 repeat region contains binding sites for Rap1p and other TPE modifiers. Thus, lengthening of a single telomere could render it more competitive in recruiting limiting silencing complexes and could enhance TPE (22). To explore the relationship between the telomere length and silencing in cis, we applied the following approach. Cells were selected for the repressed state of the URA3 gene (5-FOAR), and their telomeres were measured. The URA3-proximal telomere was significantly longer in 5-FOAR cells than in unselected cells (Fig. 5A, compare lanes 1 to 3 and 4 to 6), and vice versa, in cells with the derepressed URA3 gene (selected on an uracil-lacking agar plate), the neighboring telomere was shorter (not shown). The length of Y′-type telomeres was not changed in the cells selected for the repressed state of URA3 (Fig. 5A, compare upper and lower panels), showing that the observed effects were specific to the URA3-modified telomere. These results reveal an association between the length of the telomere and the efficiency of silencing in cis. Similar correlation was reported for ADE2 inserted near telomere VIIL (27). After 5-FOA withdrawal, cells preselected on 5-FOA-supplemented medium could maintain a high frequency of URA3 silencing and an elongated telomere proximal to the URA3 gene (Fig. 5B). In some colonies, this telomere was shortened to nearly normal size, an alteration correlated with the decreased ability of cells to grow on a 5-FOA-supplemented plate (Fig. 5B, middle and lower panels). Shortening of the affected telomere was likely mediated by the telomeric rapid deletion (TRD) pathway (27).

FIG. 5.

Telomere length in 5-FOA-resistant cells. (A) The UCC523 strain (PBP2 HEK2 ppr1− [44]) that was used in these experiments contains the URA3 gene at the end of the VR chromosome. Cells were grown on either complete medium (Complete, lanes 1 to 3) or complete medium supplemented with 5-FOA (5FOAR, lanes 4 to 6), and the individual colonies were then grown overnight in corresponding liquid media. DNA purified from the overnight cultures was cut with HindIII (upper panel) or XhoI (lower panel) and was analyzed by the Southern method with VR (upper panel) or Y′ (lower panel) probes. Arrowheads mark fragments corresponding to the probes. (B) Cells (UCC523, PBP2 HEK2 ppr1−) were grown on either complete medium (Complete, lane 1) or complete medium supplemented with 5-FOA. Individual colonies from the 5-FOA plate were then consecutively passed on two plates without selection. Several colonies from the final plate were grown overnight in liquid medium (After 5FOA, lanes 2 to 5). To assess silencing of subtelomeric URA3, overnight cultures were plated as 10-fold serial dilutions of either complete medium without (lower panel, Complete) or with (middle panel, 5FOA) 5-FOA. DNA purified from the same cultures was cut with HindIII and was analyzed by the Southern method with VR probe (upper panel) to estimate the length of the VR telomere. (C) Wild-type (WT) (UCC509, PBP2 HEK2 PPR1 RAD52) and rad52Δ mutant (DY1000, PBP2 HEK2 PPR1 rad52Δ) strains were grown on either complete (Complete, lanes 1 and 5) or 5-FOA-supplemented (5FOAR, lanes 2 to 4 and 6 to 8) media, and the length of the VR telomere was analyzed as done for panel A. In contrast to RAD52 colonies, rad52Δ colonies were small and grew slowly on 5-FOA media. Chromosomal constructs and VR probe (bold line) are shown below.

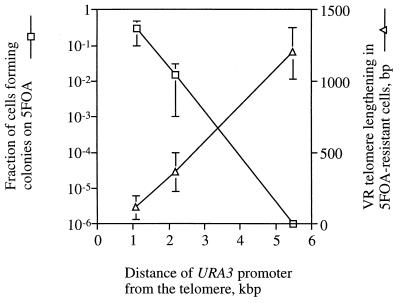

The relationship between gene silencing and telomere length in cis (Fig. 5) is further supported by the positive correlation between the extent of telomere lengthening in cells selected for the silenced URA3 (5-FOAR) and the distance between URA3 and the telomere (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

TPE and telomere lengthening depend on the distance between the ectopic URA3 and TG-repeat region. Strains (UCC519, UCC521, and UCC523, all PBP2 HEK2 ppr1− [44]) with URA3 introduced to the end of chromosome VR at distances 1.1, 2.4, and 5.2 kb from the TG1-3 repeat region were grown on either complete medium or complete medium supplemented with 5-FOA. The efficiency of URA3 silencing was measured as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The lengthening of the VR telomere in 5-FOAR cells was measured as the difference between the length of this telomere found in the cells growing in complete medium and the length found in 5-FOAR cells (VR telomere length was measured as described in the legend to Fig. 5). Results of two independent experiments with at least three individual colonies per point are shown.

The RAD52-dependent system of homologous recombination is involved in telomere length control (19, 20, 25, 32, 40). We wondered if long telomeres found in 5-FOAR cells were generated through homologous recombination. Because we were not able to find the elongated VR telomere in 5-FOAR rad52Δ cells (Fig. 5C), the dramatic elongation of the URA3-proximal telomere is likely to represent a recombination-dependent event. Cells with a modestly elongated VR telomere could still be found in the 5-FOAR rad52Δ strain (Fig. 5C, lanes 7 and 8), supporting a previous observation that short-range telomere length variations are RAD52 independent (48).

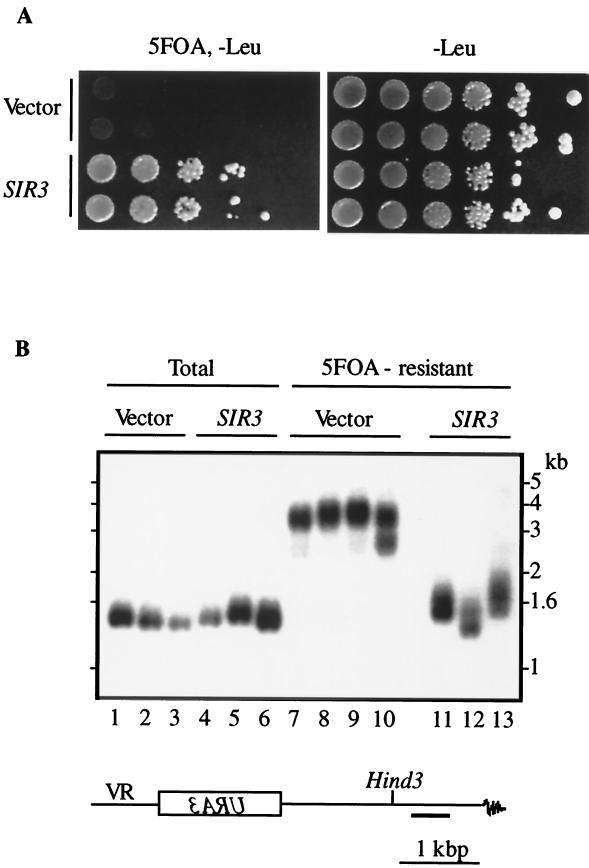

The observed lengthening of the URA3-proximal telomere in 5-FOAR cells could result from the enhanced silencing of URA3, or vice versa, lengthening of this telomere could cause enhanced silencing of the marker gene. To distinguish between the two possibilities, we increased the efficiency of URA3 silencing in the wild-type strain by overexpressing Sir3p (44) and measured the length of the neighboring telomere. The results show that the dramatically improved efficiency of URA3 silencing in the strain overexpressing Sir3p (Fig. 7A) was not associated with changes in the length of the URA3-proximal telomere (Fig. 7B, compare lanes 1 to 3 to lanes 4 to 6). Moreover, cells overexpressing Sir3p that were selected for the repressed state of URA3 (5-FOAR) have a nearly normal size for the URA3-proximal telomere (Fig. 7B, compare lanes 1 to 6 to lanes 11 to 13). In the control 5-FOAR cells, this telomere is 8 to 10 times longer than normal telomeres (Fig. 7B, compare lanes 1 to 3 to lanes 7 to 10). These results indicate that changes in the telomere length alter chromatin structure such that a longer telomere extends the chromosome region covered by silencing complexes.

FIG. 7.

Effect of SIR3 overexpression on length of telomeres. (A) UCC509 strain (PBP2 HEK2 PPR1) transformed with either pVP plasmid (2μm LEU2) (Vector) or the same plasmid containing the SIR3 gene (SIR3) was grown on agar plates lacking Leu (−Leu). Individual colonies were grown overnight in liquid −Leu medium, cells were counted, and 10-fold serial dilutions were plated on either −Leu or 5-FOA, −Leu agar plates. (B) DNA purified from the overnight cultures was cut with HindIII and analyzed by the Southern method with VR probe. Total, cells were grown on −Leu agar plates; and 5FOA-resistant, cells were grown on −Leu agar plates supplemented with 5-FOA. At least three colonies of each strain were analyzed; each lane corresponds to DNA purified from one colony. Chromosomal construct and VR-specific probe (bold line) are shown below gel.

Elongation of the telomere adjacent to the ectopic URA3 in the pbp2Δ hek2Δ cells (Fig. 3) could be a result of selection similar to the one described above for 5-FOA if, for example, URA3 expression was not favorable in the pbp2Δ hek2Δ background. However, this is not the case because there is no difference between the growth rates of PBP2 HEK2 URA3, pbp2Δ hek2Δ URA3, and pbp2Δ hek2Δ ura3-52 strains (not shown). Thus, in pbp2Δ hek2Δ cells, elongation of the telomere does not involve selection.

TRD pathway in pbp2Δ hek2Δ cells.

The length of a telomere reflects a balance between processes that elongate and shorten the TG1-3 repeat region. The pbp2Δ hek2Δ mutation could either increase the rate of telomere lengthening, decrease the rate of its shortening, or both. Next we used the following approach to test if the pbp2Δ hek2Δ mutation slowed the rate of shortening of the elongated telomere. To select cells containing elongated URA3-proximal telomere (VR), wild-type, pbp2Δ mutant, hek2Δ mutant, and pbp2Δ hek2Δ mutant cells were grown on media supplemented with 5-FOA. Selected 5-FOAR colonies were then consecutively passed three times on yeast-peptone-dextrose agar plates without selection. Individual colonies from each plate were collected, and the length of the VR telomere was measured (Fig. 8). The results show that, in the wild-type and pbp2Δ cells, the elongated VR telomere was efficiently processed to normal size, a process likely to be mediated by TRD. In contrast, hek2Δ and pbp2Δ hek2Δ mutant colonies showed delayed shortening of the VR telomere. Interestingly, a more complete reduction in the frequency of TRD occurs in the double pbp2Δ hek2Δ mutant compared to that in the single hek2Δ mutant, indicating a contribution of the pbp2Δ mutation. This observation is consistent with the finding that the double mutants display the greatest increase in telomeric silencing (Fig. 2). Thus, the pbp2Δ hek2Δ mutation inhibits TRD at the URA3-proximal telomere, an observation that could, at least in part, explain the mechanism of telomere lengthening in the mutant cells.

FIG. 8.

Effect of hek mutations on TRD. UCC509 (WT, PBP2 HEK2), DY14 (pbp2Δ HEK2), DY15 (PBP2 hek2Δ), and DY16 (pbp2Δ hek2Δ) strains carrying URA3 near the VR telomere were grown on yeast-peptone-dextrose agar plates (NS, lanes 1 and 10 in the upper panel and 1 and 9 in the lower panel) and then transferred on 5-FOA-supplemented plates. Individual 5-FOAR colonies (5FOAR, lanes 2 and 11 in the upper panel and 2 and 10 in the lower panel) were consecutively passed on three yeast-peptone-dextrose plates without selection (s1 to s3, lanes 3 to 9 and 12 to 18 in the upper panel and lanes 3 to 8 and 11 to 16 in the lower panel), with each round consisting of ∼25 generations of growth. Individual colonies from each plate were grown overnight in 2-ml cultures, DNA was isolated from each culture, and the length of the URA3-marked VR telomere was assayed as described in the legend to Fig. 3. The chromosomal construct and the position of the HindIII site used to cut DNA and the VR-specific probe (bold line) are shown below.

In vivo association of Hek2p with subtelomeric DNA.

To test the possibility that Pbp2p and Hek2p play a direct role in telomere length control, we tested if these proteins can be coprecipitated with telomeric chromatin from cellular extracts. A triple HA epitope was introduced to the 3′ ends of both ORFs. Tagging procedure abolished PBP2 function but had little effect on HEK2; therefore, we used only the HEK2-3HA construct in the chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (15, 41). We precipitated HEK2-3HA from cells cross-linked with formaldehyde in situ and analyzed coprecipitated DNA by PCR (Fig. 9). These studies demonstrate that HEK2-3HA is associated with VR subtelomeric sequences (Fig. 9A, lane 4). Other genomic loci, the Y′ box and TY1 transposable element, are bound only weakly to HEK2-3HA. The DNA-binding pattern of HEK2-3HA is clearly different from that of SIR3HA. For example, SIR3HA but not HEK2-3HA bound the subtelomeric Y′ box (Fig. 9A, compare lanes 4 and 6). This result suggests that Hek2p is not a structural constituent of telomeric chromatin. However, we found that the sir3Δ mutation decreased binding of HEK2-3HA to the VR telomere-proximal region (VR in Fig. 9A) but had little effect on binding to the telomere-distal region (VR-22kb in Fig. 9A). Densitometric analysis (Opti-Quant; Packard) showed that the VR/VR-22kb band intensity ratio was 1.35 ± 0.07 for HEK2-3HA SIR3 cells and 1.08 ± 0.11 for HEK2-3HA sir3Δ cells (mean ± standard deviation; n = 3 independent experiments). This result suggests that the binding of Hek2p to VR telomere-proximal DNA sequences is sensitive, at least in part, to alterations in telomeric chromatin. Although Hek2p DNA association could be mediated by other proteins and/or RNA, these data suggest that Hek2p plays a direct role in the observed telomeric effects.

FIG. 9.

In vivo association of Hek2p with the VR subtelomeric region. (A) Whole-cell extracts were prepared from formaldehyde cross-linked strains, and chromatin was sonicated to an average DNA size of 0.5 to 1.0 kb. Immunoprecipitations (IP) were performed with anti-HA antibody 12CA5 (αHA). Precipitated DNA was analyzed by PCR with primers specific to the VR chromosomal (Chr.) end, shown schematically in the upper panel, and by primers designed to the Y′ locus or TY1 element. Thirty PCR cycles were carried out for the VR set of primers and 25 cycles for TY1 and the Y′ set of primers. PCR products were resolved in 1% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. The DNA size standard is shown in lane 1. PCR products of immunoprecipitated DNA are shown in lanes 2 to 6. PCR products from the respective input extracts are shown in lanes 7 to 11. A threefold dilution of DNA sample from lane 11 was used in PCR, and the products are shown in lane 12. The following strains were used: UCC509 (wild type, lanes 2 and 7), DY119 (wild type, HEK2-3HA, lanes 3 and 4 and 8 and 9), DY122 (sir3Δ, HEK2-3HA, lanes 5 and 10), and AYH2.45 (wild type, SIR3HA [56], lanes 6 and 11). (B) Western blot analysis of HEK2-3HA expression. UCC509 (HEK2), DY119 (HEK2HA), and DY122 (HEK2HA sir3Δ) strains were grown exponentially. Proteins were extracted with SDS loading buffer from equal number of cells, separated by SDS-gel electrophoresis, transferred on polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and stained with anti-HA antibody 12CA5.

DISCUSSION

In this study we exploited the S. cerevisiae model system to better understand the function of the hnRNP K family of proteins. We show that two yeast K-like genes, PBP2 and HEK2, act as suppressors of TPE and regulate telomere length. These observations identify the family of K-like proteins as regulators (modifiers) of chromatin-dependent processes.

HEK genes and telomere length control.

In yeast, the length of telomeres is maintained within the narrow distribution of sizes around ∼350 bp (48, 62). The median size of the telomeric TG1–3-repeat region is, at least in part, defined by the Rap1p-dependent system (35). There are several known systems of factors that elongate or shorten telomeres to maintain their size around this median. As the cells divide, telomeres are prone to shortening because of incomplete replication of DNA ends but their shortening is prevented by the specialized telomerase complex (7, 31, 52). Cells lacking telomerase activity show gradual telomere shortening and loss of viability after ∼70 cell divisions (26, 52). In telomerase-null survivors, telomeres are maintained by the RAD52-dependent system of homologous recombination and double-strand break repair (19, 20, 25, 32, 40). While shortened telomeres are corrected by the telomerase complex and the recombination system, elongated telomeres are processed down to median sizes by the TRD pathway (27).

We have found that disruption of HEK genes increased the length of the telomeric repeat proximal to the URA3 marker gene (Fig. 3). This increase was unique to the chromosomal end that contained the marker gene, because other Y′-type or X-type telomeres were not significantly altered (Fig. 3C). Regulation of telomeric processes by Hek2p most likely reflects the direct physical interaction of this protein with subtelomeric chromatin (Fig. 9). We have further shown that the hek2Δ mutation inhibited the TRD pathway (27) at the URA3-modified telomere (Fig. 8). Telomere lengths of individual chromosomes vary among clonal populations, and telomere length heterogeneity increases with additional rounds of cell division (48). Thus, blocking the pathway (TRD) responsible for shortening of elongated telomeres at the URA3-modified telomere will result in lengthening of this telomere. The reason why the URA3-modified telomere is more sensitive than the other telomeres to the deletion of HEK genes remains to be defined. This type of chromosome-specific effects are not unique to hek mutations, since other mutations specifically altered the length of either Y′- or X-type telomeres (9), suggesting that there are telomere maintenance systems able to discriminate between telomeres, depending on subtelomeric sequences.

TRD likely involves intra- and interchromatid interactions. This assumption is based on two observations: (i) TRD is stimulated by the hpr1 mutation, which is known to enhance intrachromatid excision events and (ii) the efficiency of TRD at one telomere depends on the length of other telomeres (27). We propose that the yeast K-like protein Hek2p, along with other chromatin factors, binds subtelomeric regions and facilitates long-range interactions within and/or between telomeres. Similarly, it was recently reported that the mammalian K protein increased the frequency of interaction between two nonadjacent chromosomal loci if they were separated by an array of K-binding sites (58). It was suggested that the two loci were brought together because K protein bound and facilitated bending of the CT-enriched DNA region that separates these loci. Thus, it is conceivable that the role of Hek2p in TRD is to facilitate intrachromatid long-range interactions. It is possible that Pbp2p assists Hek2p action, because the effect of the pbp2Δ hek2Δ mutation on TPE, telomere length, and TRD was reproducibly stronger than that of the single hek2Δ mutation (Fig. 2 and 8; data not shown).

Association between length of telomere and silencing in cis.

Known TPE modifiers could either increase or decrease the average length of telomeric TG1–3 repeats at most chromosomal ends (19, 63). These data suggest that telomere length reflects changes in the structure of telomeric chromatin. In contrast, in the experiments utilizing an alternative approach to elongate a fraction of telomeres in otherwise wild-type cells, it was concluded that an elongated telomere increased the frequency of inheritance of the repressed state in cis (22, 43). Similarly, long internal tracts of TG1-3 repeat were more efficient silencers than short tracts (55). Our observations also support an association between the length of a telomere and silencing in cis. (i) Cells selected for the repressed or derepressed state of subtelomeric URA3 contain elongated or shortened adjacent telomere respectively (Fig. 5 and data not shown). These results suggest that cells with a certain length of an individual telomere could be selected from the entire cell population, where the length of telomeres varies from cell to cell (48, 62). Long telomeres were generated through RAD52-dependent events (Fig. 5C). (ii) Elongation of the URA3-proximal telomere in 5-FOAR cells is proportional to the distance from the URA3 gene to the telomere (Fig. 6). (iii) In agreement with the observation that the URA3 transcription factor Ppr1p suppresses TPE (44), we found that elongation of the URA3-proximal telomere was more dramatic in ppr1+ 5-FOAR strains than in otherwise isogenic ppr1− 5-FOAR strains (compare Fig. 5A and B, 6, and 7). (iv) Importantly, the telomere elongation in 5-FOAR cells was alleviated by overexpressed SIR3 (Fig. 7). This result suggests that the elongated telomere is more competitive for the limiting Sir3p. Taken together with the studies published by others (22, 43), our data indicate that there is a direct link between the length of telomeric TG1-3 repeat and the efficiency of silencing of neighboring genes. According to this view, the hek2Δ mutation inhibits TRD at the URA3-modified telomere; this telomere becomes longer and enhances efficiency of silencing of the adjacent URA3. In addition, there might be other telomeric processes involved where PBP2 exerts its action.

In summary, the above studies identified two yeast hnRNP K-like genes, PBP2 and HEK2. We show that these genes are involved in regulation of TPE, telomere length, and TRD. We suggest that the yeast and mammalian K proteins play a direct role in chromatin-dependent gene-silencing processes.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Akhmanova, L. Breeden, D. Gottschling, S. Grigoryev, D. Schullery, M. Shnyreva, F. van Leeuwen, and T. Young for valuable suggestions; T. Young for critical reading of the manuscript; and L. Breeden, D. Gottschling and T. Davis for yeast strains and plasmids.

This work was supported by NIH grants GM45134 and DK45978, a grant from the Northwest Kidney Foundation to K.B., and a grant from the American Heart Association, Northwest Affiliate, Inc. to O.D.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aparicio, O. M., B. L. Billington, and D. E. Gottschling. 1991. Modifiers of position effect are shared between telomeric and silent mating-type loci in S. cerevisiae. Cell 66:1279–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baber, J. L., D. Libutti, D. Levens, and N. Tjandra. 1999. High precision solution structure of the C-terminal KH domain of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K, a c-myc transcription factor. J. Mol. Biol. 289:949–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bomsztyk, K., I. Van Seuningen, H. Suzuki, O. Denisenko, and J. Ostrowski. 1997. Diverse molecular interactions of the hnRNP K protein. FEBS Lett. 403:113–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brachmann, C. B., A. Davies, G. J. Cost, E. Caputo, J. Li, P. Hieter, and J. D. Boeke. 1998. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14:115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burd, C. G., and G. Dreyfuss. 1994. Conserved structures and diversity of functions of RNA-binding proteins. Science 265:615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bustelo, X. R., K.-I. Suen, W. M. Michael, G. Dreyfuss, and M. Barbacid. 1995. Association of the vav proto-oncogene product with poly(rC)-specific RNA-binding proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:1324–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohn, M., and E. H. Blackburn. 1995. Telomerase in yeast. Science 269:396–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortes, A., D. Huertas, L. Fanti, S. Pimpinelli, F. X. Marsellach, B. Pina, and F. Azorin. 1999. DDP1, a single-stranded nucleic acid-binding protein of Drosophila, associates with pericentric heterochromatin and is functionally homologous to the yeast Scp160p, which is involved in the control of cell ploidy. EMBO J. 18:3820–3833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craven, R. J., and T. D. Petes. 1999. Dependence of the regulation of telomere length on the type of subtelomeric repeat in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 152:1531–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delling, U., M. Raymond, and E. Schurr. 1998. Identification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae genes conferring resistance to quinoline ring-containing antimalarial drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1034–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denisenko, O. N., and K. Bomsztyk. 1997. The product of the murine homolog of the Drosophila extra sex combs gene displays transcriptional repressor activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:4707–4717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denisenko, O. N., B. O’Neill, J. Ostrowski, I. Van Seuningen, and K. Bomsztyk. 1996. Zik, a transcriptional repressor that interacts with the heterogenous nuclear ribonuclear particle K protein. J. Biol. Chem. 271:27701–27706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottschling, D. E., O. M. Aparicio, B. L. Billington, and V. A. Zakian. 1990. Position effect at S. cerevisiae telomeres: reversible repression of Pol II transcription. Cell 63:751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greider, C. W. 1996. Telomere length regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65:337–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hecht, A., S. Strahl-Bolsinger, and M. Grunstein. 1996. Spreading of transcriptional repressor SIR3 from telomeric heterochromatin. Nature 383:92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hobert, O., B. Jallal, J. Schlessinger, and A. Ullrich. 1994. Novel signaling pathway suggested by SH3 domain-mediated p95vav/heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein K interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 269:20225–20228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman, C. S., and F. Winston. 1987. A ten-minute DNA preparation from yeast efficiently releases autonomous plasmids for transformation of Escherichia coli. Gene 57:267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh, T. Y., M. Matsumoto, H. C. Chou, R. Schneider, S. B. Hwang, A. S. Lee, and M. M. C. Lai. 1998. Hepatatis C virus core protein interacts with heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K. J. Biol. Chem. 273:17651–17659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kass-Eisler, A., and C. W. Greider. 2000. Recombination in telomere-length maintenance. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:200–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kironmai, K. M., and K. Muniyappa. 1997. Alteration of telomeric sequences and senescence caused by mutations in RAD50 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Cells 2:443–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konkel, L. M. C., S. Enomoto, E. M. Chamberlain, P. McCune-Zierath, S. J. P. Iyadurau, and J. Berman. 1995. A class of single-stranded telomeric DNA-binding proteins required for Rap1p localization in yeast nuclei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:5558–5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kyrion, G., K. Liu, C. Liu, and A. J. Lustig. 1993. RAP1 and telomere structure regulate telomere position effects in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 7:1146–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaBranche, H., S. Dupuis, Y. Ben-David, M. R. Bani, R. J. Wellinger, and B. Chabot. 1998. Telomere elongation by hnRNP A1 and a derivative that interacts with telomeric repeats and telomerase. Nat. Genet. 19:199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lacroix, L., H. Lienard, E. Labourier, M. Djavaheri-Mergny, J. Lacoste, H. Leffers, J. Tazi, C. Helene, and J. L. Mergny. 2000. Identification of two human nuclear proteins that recognise the cytosine-rich strand of human telomeres in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:1564–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le, S., J. K. Moore, J. E. Haber, and C. W. Greider. 1999. RAD50 and RAD51 define two pathways that collaborate to maintain telomeres in the absence of telomerase. Genetics 152:143–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lendvay, T. S., D. K. Morris, J. Sah, B. Balasubramanian, and V. Lundblad. 1996. Senescence mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with a defect in telomere replication identify three additional EST genes. Genetics 144:1399–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, B., and A. J. Lustig. 1996. A novel mechanism for telomere size control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 10:1310–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loison, G., R. Losson, and F. Lacroute. 1980. Constitutive mutants for orotidine-5-phosphate decarboxylase and dihydroorotic acid dehydrogenase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 2:39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowell, J. E., and L. Pillus. 1998. Telomere tales: chromatin, telomerase and telomere function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 54:32–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lue, N. F., and J. C. Wang. 1995. ATP-dependent processivity of a telomerase activity from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 270:21453–21456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lundblad, V., and E. H. Blackburn. 1993. An alternative pathway for yeast telomere maintenance rescues est1− senescence. Cell 73:347–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lundblad, V., and J. W. Szostak. 1989. A mutant with a defect in telomere elongation leads to senescence in yeast. Cell 57:633–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mangus, D. A., N. Amrani, and A. Jacobson. 1998. Pbp1p, a factor interacting with Saccharomyces cerevisiae poly(A)-binding protein, regulates polyadenylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:7383–7396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marcand, S., E. Gilson, and D. Shore. 1997. A protein-counting mechanism for telomere length regulation in yeast. Science 275:986–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matunis, M. J., W. M. Michael, and G. Dreyfuss. 1992. Characterization and primary structure of the poly(C)-binding heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex K protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matunis, M. J., J. Xing, and G. Dreyfuss. 1994. The hnRNP K protein: unique primary structure, nucleic acid-binding properties, and subcellular localization. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:1059–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michael, W. M., P. S. Eder, and G. Dreyfuss. 1997. The K nuclear shuttling domain: a novel signal for nuclear import and nuclear export in the hnRNP K protein. EMBO J. 16:3587–3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michelotti, E. F., G. A. Michelotti, A. I. Aronsohn, and D. Levens. 1996. Heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K is a transcription factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:2350–2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nugent, C. I., G. Bosco, L. O. Ross, S. K. Evans, A. P. Salinger, J. K. Moore, J. E. Haber, and V. Lundblad. 1998. Telomere maintenance is dependent on activities required for end repair of double-strand breaks. Curr. Biol. 8:657–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orlando, V., and R. Paro. 1993. Mapping polycomb-repressed domains in the bithorax complex using in vivo formaldehyde cross-linked chromatin. Cell 75:1187–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ostrowski, J., Y. Kawata, D. S. Schullery, O. N. Denisenko, Y. Higaki, C. K. Abrass, and K. Bomsztyk. 2001. Insulin alters heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K protein binding to DNA and RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:9044–9049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park, Y., and A. J. Lustig. 2000. Telomere structure regulates the heritability of repressed subtelomeric chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 154:587–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Renauld, H., O. M. Aparicio, P. D. Zierath, B. L. Billington, S. K. Chhablani, and D. E. Gottschling. 1993. Silent domains are assembled continuously from the telomere and are defined by promoter distance and strength, and by SIR3 dosage. Genes Dev. 7:1133–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sandell, L. L., D. E. Gottschling, and V. A. Zakian. 1994. Transcription of a yeast telomere alleviates telomere position effect without affecting chromosome stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:12061–12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmitt, M. E., T. A. Brown, and B. L. Trumpower. 1990. A rapid and simple method for preparation of RNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:3091–3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schullery, D. S., J. Ostrowski, O. N. Denisenko, L. Stempka, M. Shnyreva, H. Suzuki, M. Gschwendt, and K. Bomsztyk. 1999. Regulated interaction of protein kinase Cdelta with the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K protein. J. Biol. Chem. 274:15101–15109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shampay, J., and E. H. Blackburn. 1988. Generation of telomere-length heterogeneity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:534–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shampay, J., J. W. Szostak, and E. H. Blackburn. 1984. DNA sequences of telomeres maintained in yeast. Nature 310:154–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shnyreva, M., D. S. Schullery, H. Suzuki, Y. Higaki, and K. Bomsztyk. 2000. Interaction of two multifunctional proteins. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K and Y-box-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 275:15498–15503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122:19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singer, M. S., and D. E. Gottschling. 1994. TLC1: template RNA component of Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomerase. Science 266:404–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singer, M. S., A. Kahana, A. J. Wolf, L. L. Meisinger, S. E. Peterson, C. Goggin, M. Mahowald, and D. E. Gottschling. 1998. Identification of high-copy disruptors of telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 150:613–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siomi, H., M. J. Matunis, W. M. Michael, and G. Dreyfuss. 1993. The pre-mRNA binding protein contains a novel evolutionary conserved motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:1193–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stavenhagen, J. B., and V. A. Zakian. 1994. Internal tracts of telomeric DNA act as silencers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 8:1411–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strahl-Bolsinger, S., A. Hecht, K. Luo, and M. Grunstein. 1997. SIR2 and SIR4 interactions differ in core and extended telomeric chromatin in yeast. Genes Dev. 11:83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor, S. J., and D. Shalloway. 1994. An RNA-binding protein associated with Src through SH2 and SH3 domains in mytosis. Nature 368:867–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tomonaga, T., G. A. Michelotti, D. Libutti, A. Uy, B. Sauer, and D. Levens. 1998. Unrestraining genetic processes with a protein-DNA hinge. Mol. Cell 1:759–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van Seuningen, I., J. Ostrowski, X. Bustelo, P. Sleath, and K. Bomsztyk. 1995. The K protein domain that recruits the IL-1-responsive K protein kinase lies adjacent to a cluster of Src- and Vav-SH3-binding sites. Implications that K protein acts as a docking platform. J. Biol. Chem. 270:26976–26985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Venditti, S., M. A. Vega-Palas, G. Di Stefano, and E. Di Mauro. 1999. Imbalance in dosage of the genes for the heterochromatin components Sir3p and histone H4 results in changes in the length and sequence organization of yeast telomeres. Mol. Gen. Genet. 262:367–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vojtek, A. B., S. M. Hollenberg, and J. A. Cooper. 1993. Mammalian Ras interacts directly with the serine/threonine kinase Raf. Cell 74:205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walmsley, R. M., and T. D. Petes. 1985. Genetic control of chromosome length in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:506–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zakian, V. A. 1996. Structure, function, and replication of Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomeres. Annu. Rev. Genet. 30:141–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]