Abstract

The EcoO109I restriction-modification system, which recognizes 5′-(A/G)GGNCC(C/T)-3′, has been cloned, and contains convergently transcribed endonuclease and methylase. The role and action mechanism of the gene product, C.EcoO109I, of a small open reading frame located upstream of ecoO109IR were investigated in vivo and in vitro. The results of deletion analysis suggested that C.EcoO109I acts as a positive regulator of ecoO109IR expression but has little effect on ecoO109IM expression. Assaying of promoter activity showed that the expression of ecoO109IC was regulated by its own gene product, C.EcoO109I. C.EcoO109I was overproduced as a His-tag fusion protein in recombinant Escherichia coli HB101 and purified to homogeneity. C.EcoO109I exists as a homodimer, and recognizes and binds to the DNA sequence 5′-CTAAG(N)5CTTAG-3′ upstream of the ecoO109IC translational start site. It was also shown that C.EcoO109I bent the target DNA by 54 ± 4°.

INTRODUCTION

A type II restriction endonuclease, R.EcoO109I, which recognizes and cleaves the nucleotide sequence 5′-(A/G)G↓ GNCC(C/T)-3′, has been isolated from Escherichia coli H709c, an anti-genetic tester strain of E.coli O109 (1). A DNA fragment carrying the genes for the EcoO109I restriction-modification (R-M) system has been cloned from chromosomal DNA, and the complete nucleotide sequence was determined (2). The R.EcoO109I and M.EcoO109I genes showed convergent alignment and were each expected to be regulated by their own autogeneous promoter. More than 3000 type II R-M systems have been identified and the nucleotide sequences have been determined for about 150 systems (3). In several R-M systems such as BamHI (4) and PvuII (5), a small protein is produced and acts in trans to stimulate the expression of R endonuclease. This protein has been named C (for controller), and its gene generally precedes and in some cases partially overlaps the R endonuclease gene. A small open reading frame (ORF) is located upstream of the R.EcoO109I gene and partially overlaps the gene. Although the deduced amino acid sequence of C.EcoO109I shows slight homology to those of the other control elements, which are associated with several type II R-M systems, the molecular mass (11 455 Da) was in good agreement with the predicted sizes of other control elements. The product of the ORF might be involved in regulation of the EcoO109I R-M system. In accordance with the accepted nomenclature (5), the putative protein was designated as C.EcoO109I. A conserved DNA sequence element termed a ‘C box’ was found immediately upstream of the C gene (6), and it was shown that the PvuII C box sequence was at least one target of C.PvuII binding (7). No ‘C box’ like sequence was found upstream of the ecoO109IC translational start site.

Because some R-M systems have been indicated to behave as mobile genetic elements, regulation of an R-M system is important for (i) establishment of the system, when it is transferred via a plasmid or phage to a new host with unprotected DNA by cognate or other appropriate methyltransferases, or (ii) maintenance of the system as a ‘selfish gene’, when competitive R-M systems invade and lead to competitive exclusion of the native one (8,9). We have obtained evidence that the EcoO109I R-M system was horizontally transferred to E.coli chromosomal DNA by the P4 phage, based on the nucleotide sequence surrounding the R-M gene. A cell’s DNA must be completely protected by M.EcoO109I before R.EcoO109I can act on the invading DNA, in other words, C.EcoO109I might generate a timing delay, allowing M.EcoO109I to appear before R.EcoO109I in a new host cell, e.g. E.coli H709c.

In this paper, we describe the regulation of both ecoO109IR and ecoO109IM by C.EcoO109I, and characterize C.EcoO109I as a DNA-binding protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and strains

Escherichia coli HB101 (10) and JM109 (11) were used as host strains. Plasmids pACYC184 and pBluescriptII SK were from our collection.

Plasmids p184CRM, p184dCRM and p184intCRM were constructed as follows: a 3.2-kb XbaI–AviII fragment that carried the genes for R.EcoO109I, M.EcoO109I, and a putative regulatory protein (C.EcoO109I) was excised from pKF3-1 (2), and then inserted into the XbaI and HincII sites of pACYC184 to construct p184CRM. A 0.5-kb SmaI–HpaI fragment was deleted from p184CRM, followed by self-ligation to construct p184dCRM. Oligonucleotides 5′-AAT TGATTCTTAA-3′ and 5′-TTAAGAATCAATT-3′ were annealed and then inserted into the HpaI site of p184CRM to construct p184intCRM, in which the ecoO109IC gene was disrupted.

pBSCEcoO109I was constructed as follows: two primers, primer C109N (5′-CCTACCTCTAGAAAGAGGATTTTCG-3′), which was flanked by a XbaI site, and primer C109C (5′-TTTAAGTATAGGATCCTGCTTATTCATGAC-3′), which was flanked by a BamHI site, were used to subclone the ecoO109IC gene. Plasmid pKF3-1 was used as the template for PCR. The profile (30 s at 94°C, 1 min at 60°C and 1 min at 72°C) was repeated for 30 cycles. The PCR-generated DNA fragment was digested with XbaI and BamHI, ligated into pBluescriptII SK cleaved with XbaI and BamHI, and then transformed into E.coli JM109. pBSCEcoO109I–Hisx6 was constructed as follows: primers C109N and C109CH (5′-GGATCCTTAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGTTCATGACTTATAAATCCATCTG-3′), which was flanked by a BamHI site and added a six amino acid tag (Hisx6) to the C-terminal end of C.EcoO109I, were used to subclone the ecoO109IC–Hisx6 gene. Plasmid pBSCEcoO109I was used as the template for PCR. The profile (30 s at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C and 1 min at 72°C) was repeated for 30 cycles. The PCR-generated DNA fragment was digested with XbaI and BamHI, ligated into pBluescriptII SK cleaved with XbaI and BamHI, and then transformed into E.coli JM109.

The culture medium for recombinant E.coli was LB broth comprising 1% Bacto tryptone peptone, 0.5% Bacto yeast extract and 1% NaCl, pH 7.0. When necessary, ampicillin (100 µg/ml) and chloramphenicol (25 µg/ml) were added to the medium.

Purification of C.EcoO109I–Hisx6

For purification of C.EcoO109I–Hisx6, cells of E.coli HB101 carrying pBSCEcoO109I–Hisx6 were grown at 37°C in 500 ml of LB broth containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin and 1 mM IPTG for 20 h. Cells were harvested, washed with 0.15 M NaCl in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), and then stored at –20°C. Frozen cells were suspended in 20 ml of a buffer comprising 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM imidazole and 0.5 M NaCl. The cells were disrupted by sonication and cell debris was removed by centrifugation. The supernatant was applied to a His-Bind column (Novagen), washed with 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 12 mM imidazole, 0.5 M NaCl, and then eluted with a linear 0.012–1 M imidazole gradient with a simultaneous linear decrease in NaCl concentration from 0.5 to 0.25 M in 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0). The fraction containing C.EcoO109I was stored at –20°C. The molecular weight of C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 was measured on HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-100 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) using 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 0.325 M imidazole and 0.5 M NaCl as the elution buffer.

Measurement of promoter activity

Promoter assay vector pMCLTerAR was constructed as follows: to amplify the aldehyde reductase (AR1) gene from Sporobolomyces salmonicolor AKU4429 (12), two primers, primer ARN (5′-GGTACCGGAGGTATTATATGGTCGGCAC-3′), which contained a Shine–Dalgarno sequence (underlined nucleotides) (13) and a KpnI site, and primer ARC (5′-GGTACCCTACTTGATCTTCACGGCGTTCTTG-3′), which was flanked by a KpnI site, were used. Plasmid pKAR (12) was used as the template for PCR. The profile (30 s at 94°C, 1 min at 60°C and 2 min at 72°C) was repeated for 30 cycles. The PCR-generated DNA fragment was digested with KpnI, ligated into pMCL210 (14) cleaved with KpnI, and then transformed into E.coli JM109. Several clones were picked up and plasmid DNA was examined by restriction analysis to select the pMCLAR in which the AR1 gene was inserted in the same direction as the chloramphenicol acetyltranferase gene. The 0.5-kb fragment encoding rrnBT1T2 was excised from pKK232-8 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) with PvuII and EaeI, and then ligated to pMCLAR digested with NotI and Bst1107I to construct pMCLTerAR.

The DNA fragment to be assayed for promoter activity was amplified using PCR with selected primers and pKF3-1 as the template. The PCR products were ligated into the pGEM-T vector (Promega). The DNA fragments were excised with ApaI and SpeI, and then ligated into ApaI–SpeI-digested pMCLTerAR.

The activity of AR1 was determined at 37°C by measuring the rate of the decrease in the absorbance at 340 nm (12). The standard reaction mixture (1.0 ml) comprised 0.2 mM 4-chloro-3-oxobutanoate ethyl ester (4-COBE), 0.2 mM NADPH and 200 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzed the oxidation of 1 µmol of NADPH per minute.

DNA-binding assay

The DNA fragments isolated from a plasmid and synthetic oligoduplexes were labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and T4 polynucleotide kinase, and then used as substrates. The binding activity was assayed by incubation for 30 min at 37°C in 10 µl of a reaction mixture comprising 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT and 50 nM substrate DNA. Immediately after the addition of 2.4 µl of a loading solution (30% glycerol, 30 mM EDTA, 0.03% BPB and 0.03% Xylene cyanol), samples were electrophoresed on 8 or 12% polyacrylamide gels in 0.5× TBE. The protein–DNA complexes were detected by autoradiography.

DNA-bending assay

The synthetic oligonucleotides encoding the C.EcoO109I-binding site were ligated into the XbaI–SalI site of pBend2 (15) to construct pBend109. Different DNA fragments containing a single C.EcoO109I-binding site were isolated by digesting pBend109 with proper sets of restriction enzymes, and the resulting DNA fragments were isolated by gel electrophoresis and then labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. Binding of C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 to DNA was performed as described above.

Other methods

C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 from E.coli HB101 carrying pBSCEcoO109I– Hisx6 was blotted from an SDS–polyacrylamide gel to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane by the method of Matsudaira (16), and then subjected to N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis. Antibodies were raised against either R.EcoO109I or M.EcoO109I, which were purified almost homogeneously as described elsewhere (2,17). The western blots were probed first with a purified antibody and then anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G coupled to alkaline phosphatase. Blocking and probing with antibodies were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (18). Ni-NTA AP conjugates (Qiagen) were used for detection of the Hisx6-tagged protein according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein was assayed by the method of Bradford (19) using a kit from Bio-Rad with BSA as the standard. SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was performed by the method of Laemmli (20).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Effect of C.EcoO109I on production of R.EcoO109I and M.EcoO109I

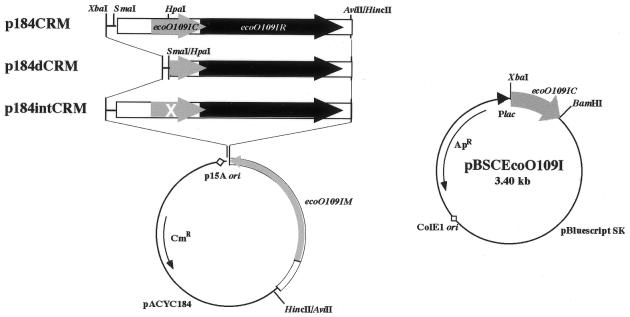

The effect of C.EcoO109I on the production of R.EcoO109I and M.EcoO109I was investigated by constructing a deletion mutant of the 5′-untranslated region and a frame-shift mutant of ecoO109IC. A DNA fragment carrying the complete EcoO109I R-M system was subcloned into pACYC184, p184CRM being generated, and then mutations were introduced into ecoO109IC: one (p184dCRM) by deleting the 0.5-kb DNA fragment carrying the gene encoding the N-terminal and 5′-untranslated regions of ecoO109IC, and the other (p184intCRM) by inserting a nonsense mutation at the HpaI site. As shown in Figure 1, we also put ecoO109IC under the control of the lac promoter of pBluescriptII SK to supply C.EcoO109I in trans.

Figure 1.

Structures of plasmids carrying the wild-type and mutant ecoO109IC. Construction of these plasmids is described in the Materials and Methods. ApR, β-lactamase gene; CmR, chloramphenicol acetyl transferase gene; Plac, lac promoter. X in p184intCRM indicates the stop codon.

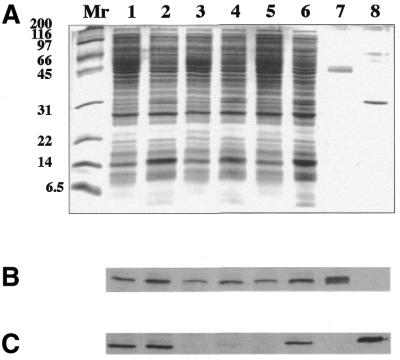

Cotransformants of E.coli HB101, carrying the plasmids derived from p184CRM and pBSCEcoO109I, were grown, and the R.EcoO109I and M.EcoO109I produced in cell-free extracts were examined by western blot analysis. Figure 2 shows that the production of M.EcoO109I appears to be unchanged whether ecoO109IC is mutated or not, or C.EcoO109I is provided in trans or not. It can be concluded that C.EcoO109I does not function as a specific regulator of ecoO109IM.

Figure 2.

Production of R.EcoO109I and M.EcoO109I in E.coli cells carrying the wild-type and mutant ecoO109IC. Escherichia coli HB101 cells carrying p184CRM (lanes 1 and 2), p184dCRM (lanes 3 and 4), and p184intCRM (lanes 5 and 6) were transformed with pBSCEcoO109I (lanes 2, 4 and 6) or not (lanes 1, 3 and 5), and then cultured at 37°C in LB broth containing 1 mM IPTG. Cell-free extracts prepared from recombinant E.coli HB101 cells were separated by 0.1% SDS–15% PAGE (A), and then analyzed by western blotting with antibodies raised against M.EcoO109I (B) and R.EcoO109I (C), respectively. The positions of molecular mass standards (Mr) are indicated (in kDa) on the left. Lanes 7 and 8 show purified M.EcoO109I and R.EcoO109I, respectively.

In contrast to M.EcoO109I, the production of R.EcoO109I decreased to below the limit of detection when ecoO109IC was disrupted, but returned to a normal level when ecoO109IC was supplied in trans. When a DNA fragment upstream of ecoO109IC was deleted, no restoration of production was observed on supplying ecoO109IC in trans. These results suggest that ecoO109IC and ecoO109IR are cotranscribed under the control of the ecoO109IC promoter, and that C.EcoO109I acts as a positive regulator of both ecoO109IC and ecoO109IR expression. In other words, the accumulation of C.EcoO109I in a cell is required for the production of R.EcoO109I.

Based on the nucleotide sequence surrounding the R-M gene, we have assumed that the EcoO109I R-M system is horizontally transferred to E.coli chromosomal DNA via P4 phage integration. Regulation of the R-M system is important, especially when the system is transferred to a new host with unprotected DNA, that is, the cellular DNA must be completely protected by the methylase before the endonuclease can act on invading DNA. It is assumed from our results that just after the EcoO109I R-M system is transferred to E.coli H709c, M.EcoO109I is synthesized but R.EcoO109I is not, because of the absence of C.EcoO109I; after a while, C.EcoO109I accumulates in the cell, and then triggers the synthesis of R.EcoO109I.

A protein that has been shown to play an important role in regulation of the R-M system has been discovered in some R-M systems, and is named C (5). Its gene generally precedes and in some cases partially overlaps the R gene. We demonstrated that in the EcoO109I R-M system as well as in the BamHI (4), PvuII (5) and EcoRV (9) systems, C protein acts in trans and is required for the production of cognate restriction endonuclease. A conserved DNA sequence element termed a ‘C box’ has been identified immediately upstream of bamHIC and pvuIIC (6), however, it was not found upstream of ecoO109IC or ecoO109IM. Moreover, no significant homology has been detected between C.EcoO109I and other C proteins. We assumed that the site of action of C.EcoO109I is distinct from those of C.BamHI and C.PvuII, and investigated the mechanism of C.EcoO109I action in vivo and in vitro.

Promoter activity of various DNA fragments upstream of ecoO109IC and ecoO109IM

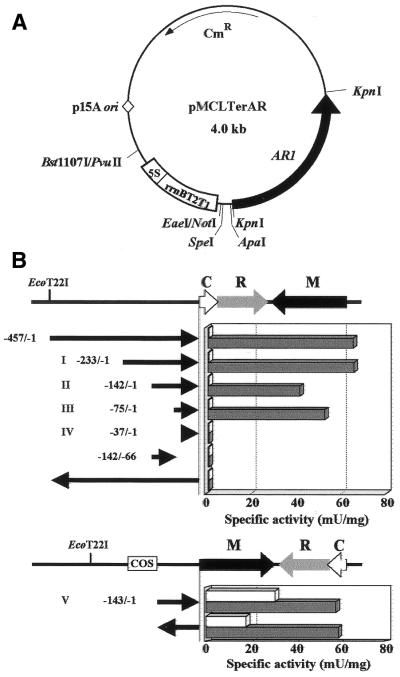

To determine the location and C.EcoO109I responsiveness of EcoO109I promoters, we cloned the putative promoter region for each of the genes upstream of the promoterless NADPH-dependent aldehyde reductase (AR1) (EC 1.1.1.2) gene in plasmid pMCLTerAR (Fig. 3A). Fragments to be assayed for promoter activity were PCR-amplified with selected oligonucleotide primers, and DNA products were inserted between the SpeI and ApaI sites of the promoter screening vector, pMCLTerAR, in both orientations. Bacterial cell extracts were prepared and enzyme assays were carried out using 4-COBE as a substrate (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

5′-Deletion analysis of the 5′-flanking regions of ecoO109IC and ecoO109IM. (A) Structure of the promoter assay vector. (B) Promoter activity associated with various DNA fragments. The segments were cloned upstream of a promoterless AR1 gene in vector pMCLTerAR. The arrows indicate the orientation of segments inserted between SpeI and ApaI sites. The nucleotide preceeding the translational start codon (ATG for ecoO109IC and TTG for ecoO109IM) is designated as –1. Each clone was assayed for AR1 activity in the presence (solid bars) or absence (open bars) of C.EcoO109I.

In the absence of C.EcoO109I, the promoter activity of a 143-bp fragment upstream of ecoO109IM was high enough, but that of a 457-bp fragment upstream of ecoO109IC was below the limit of detection. However, in the presence of C.EcoO109I, the promoter activity of the 143-bp fragment upstream of ecoO109IM increased to twice as much as in the absence of C.EcoO109I, and that of the 457-bp fragment upstream of ecoO109IC became comparable with the ecoO109IM promoter activity. We do not have any ideas to explain why C.EcoO109I induces a 2–3-fold increase of reporter gene expression when a DNA fragment which is originally located upstream of ecoO109IM is inserted in both orientations upstream of the reporter gene. Activation of the ecoO109IC promoter by C.EcoO109I required at least 75 bp upstream of the translational start site of ecoO109IC.

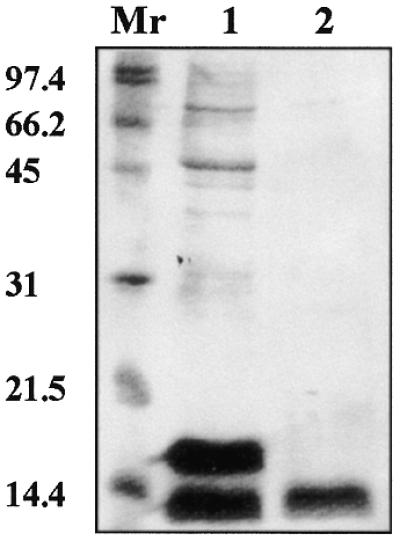

Purification of C.EcoO109I–Hisx6

In order to test the ability of C.EcoO109I to bind to DNA in a sequence-specific manner, we constructed a plasmid which expresses C.EcoO109I–Hisx6, a fusion protein consisting of C.EcoO109I and a hexahistidine affinity domain (Hisx6) at the C-terminus, and purified the protein from recombinant E.coli. Escherichia coli cells harboring pBSCEcoO109I–Hisx6 and pMCLTerAR457, which carries the 457-bp DNA upstream of ecoO109IC in the same direction as the AR1 gene, showed 70% AR1 activity compared with those carrying pBSCEcoO109I and pMCLTerAR457 (data not shown). This indicates that the addition of Hisx6-tag to the C-terminus does not significantly affect the action of C.EcoO109I in vivo. As shown in Figure 4, two major proteins were eluted from an Ni(II)-charged column with 0.3–0.35 M imidazole. After the solution had been frozen at –20°C followed by melting on ice, a protein with a molecular mass of 12.4 kDa (Fig. 4, lane 2) was recovered in the supernatant fraction on removal of a finely dispersed precipitate. The protein was blotted onto a membrane and then subjected to N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis. The first 10 amino acids of the protein were MLPIRLKKAR, which was identical to the sequence deduced from the nucleotide sequence. The presence of the Hisx6-tag was confirmed by western blot analysis using anti-Hisx6-tag antibodies (data not shown). The predicted mass of the fusion protein, 12 277, was close enough to the value estimated by SDS–PAGE. These results strongly suggest that the purified protein was C.EcoO109I–Hisx6. In contrast, the first 10 amino acids of a protein with a molecular mass of 15.6 kDa (Fig. 4, lane 1) were TMITPSAQLT, which was identical to the N-terminal amino acid sequence of β-galactosidase in pBluescriptII (21). In plasmid pBSCEcoO109I–Hisx6, the lac promoter directs transcription of the N-terminus of lacZ gene followed by an in-frame C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 gene. Consequently, induction of the lac promoter results in the production of two proteins, C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 and the fusion protein of β-galactosidase and C.EcoO109I–Hisx6.

Figure 4.

SDS–PAGE of the C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 obtained from E.coli HB101. Fractions containing C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 eluted from the His-Bind column were collected and stored at –20°C. A finely dispersed precipitate appearing on melting was removed by centrifugation, and the resulting clear solution (lane 2) and eluted fractions (lane 1) were separated on a 0.1% SDS–15% polyacrylamide gel. The positions of molecular mass standards (Mr) are indicated (in kDa) on the left.

Attempts to remove NaCl and imidazole from the protein solution by gel filtration or dialysis failed, because of the poor solubility of the protein in a low ionic strength solution. When purified C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 was stored at 4°C in the elution buffer used for Ni(II)-charged column chromatography for 5 months, neither precipitation nor loss of DNA-binding activity was observed. The molecular mass of the native protein, which was measured by HiTrap Sephacryl S-100 gel filtration using 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 0.5 M NaCl and 0.325 M imidazole as the elution buffer, was estimated to be 35 kDa. Although the determined molecular mass exceeds the deduced one three times, we assume that C.EcoO109I dimerizes but does not form a globular structure, and binds to a palindromic sequence.

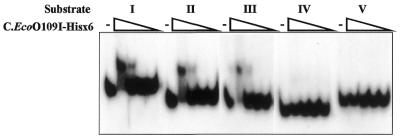

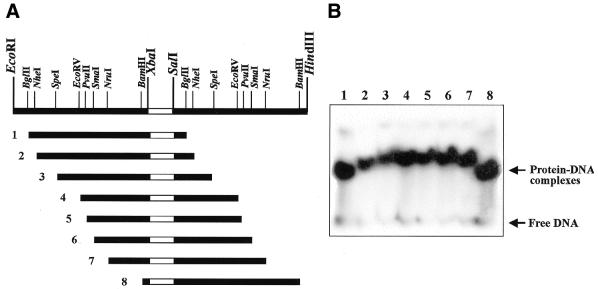

DNA-binding activity of C.EcoO109I–Hisx6

We have examined whether or not C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 binds to the DNA fragments which were examined for promoter activity by gel mobility shift assaying. DNA fragments I–V in Figure 3 were excised from each plasmid by digestion with SpeI and ApaI, and then incubated with C.EcoO109I–Hisx6. As shown in Figure 5, C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 bound to the DNA segments of longer than 75 bp but not to that of 37 bp upstream of ecoO109IC. In contrast, C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 did not bind to the 143-bp DNA segment upstream of ecoO109IM. These results indicate that the binding of C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 is correlated with stimulation of the promoter activity of ecoO109IC, and it is suggested that C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 binds to the –75 to –38 region upstream of the ecoO109IC translational start site. As indicated in Figure 6A, the –70 to –46 region consists of a 2-fold symmetrical sequence with an axis of symmetry at –58 and is expected to be the binding site of C.EcoO109I–Hisx6.

Figure 5.

Gel mobility shift assays with DNA fragments upstream of ecoO109IC and ecoO109IM. The substrate DNAs (I–V) indicated in Figure 3 were incubated with 9, 3, 1 and 0.33 pmol of purified C.EcoO109I–Hisx6, and then separated on a 8% polyacrylamide gel. The wedges indicate decreasing amounts of protein added.

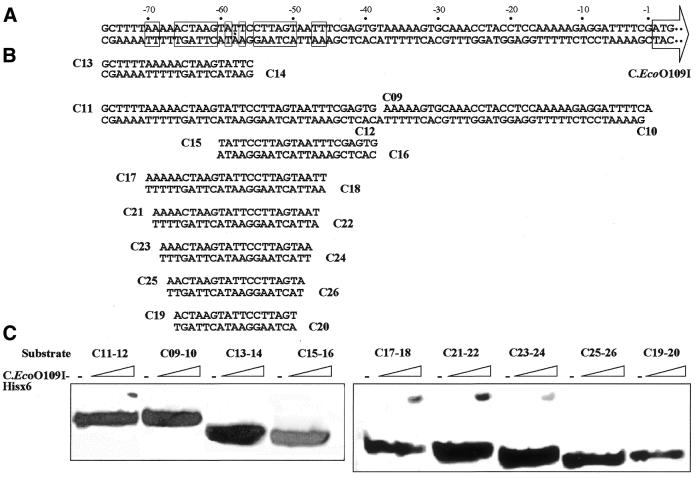

Figure 6.

Interaction of C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 with various oligoduplexes. (A) DNA sequence upstream of the ecoO109IC translational start site. The base pairs constituting the 2-fold symmetrical sequences are boxed. (B) Oligonucleotides used for assaying. (C) Gel mobility shift analysis with oligoduplexes. Oligoduplexes were incubated with 1, 3 and 9 pmol of purified C.EcoO109I–Hisx6, and separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel. The wedges indicate increasing amounts of protein added.

Oligonucleotides of various lengths with the DNA sequence upstream of ecoO109IC were synthesized and used for binding assays. C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 bound to oligoduplexes (C11–12) covering –76 to –39 but not to oligoduplexes (C09–10) covering –38 to –1, oligoduplexes (C13–14) covering –76 to –56, or oligoduplexes (C15–16) covering –60 to –39 (Fig. 6C). These results strongly suggested that C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 recognizes and binds to the 2-fold symmetrical sequence. In order to determine the minimum length to which C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 binds, substrate oligoduplexes containing 25–17 bp were synthesized and used for binding assays. C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 bound to oligoduplexes of longer than 21 bp but did not bind to oligoduplexes of shorter than 19 bp. This indicates that the outer two AT base pairs in the 25-bp symmetrical sequence shown in Figure 6A were not indispensable for binding to C.EcoO109I–Hisx6.

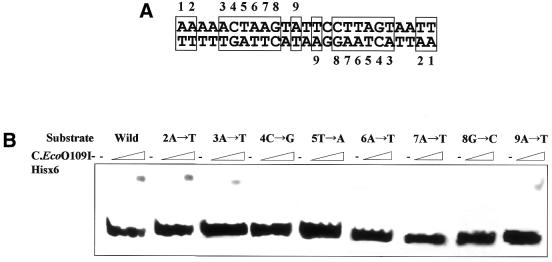

In order to identify the base pairs that play a control role in recognition of C.EcoO109I, oligoduplexes bearing base-pair substitutions at nine positions of the 25-bp symmetrical sequence shown in Figure 7A were examined for binding to C.EcoO109I–Hisx6. As expected from the results shown in Figure 6, substitution at the second position did not affect the binding. Substitutions at the third and ninth positions slightly decreased the C.EcoO109I binding, but ones at the fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh and eighth positions completely abolished the C.EcoO109I binding. We constructed a series of mutant oligoduplexes with different spacer lengths between the inverted repeat, and examined for binding of C.EcoO109I. As seen in Figure 8, C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 bound to neither the oligoduplexes with a 1-, 3- or 5-bp deletion nor those with a 1-, 3- or 5-bp insertion. These results demonstrate that C.EcoO109I recognizes and binds to the sequence 5′-CTAAG(N)5CTTAG-3′, composed of 5-bp inverted repeats at 5-bp intervals. DNA-binding activity has been examined for C.PvuII using 22-bp oligoduplexes containing the originally proposed PvuII C box sequence located –54 to –30 upstream of the pvuIIC translational start site, and the dyad consensus sequence GACT(N)3AGTC is at least one target of C.PvuII binding (7). The target sequence of C.EcoO109I is quite distinct from that of C.PvuII.

Figure 7.

Gel mobility shift analysis with oligoduplexes with base substitutions. (A) DNA sequences of oligonucleotides. The base pairs constituting the 2-fold symmetrical sequence are boxed, and are numbered from 1 to 9. (B) Oligoduplexes of the wild-type and mutant sequences were incubated with 1, 3 and 9 pmol of purified C.EcoO109I–Hisx6, and then separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel. The wedges indicate increasing amounts of protein added.

Figure 8.

Gel mobility shift analysis with oligoduplexes with deletion (A) and insertion (B) between the inverted repeat. DNA sequences of the upper strand of oligoduplexes are shown, and the inverted repeat is underlined. Oligoduplexes of the wild-type and mutant sequences were incubated with 9 pmol of purified C.EcoO109I–Hisx6, and then separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel.

DNA-bending by C.EcoO109I–Hisx6

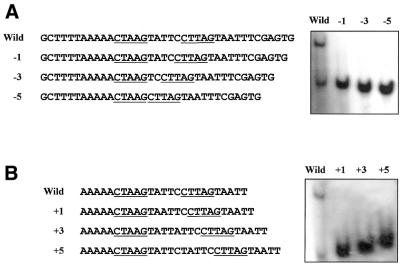

Sequence-specific binding of proteins to DNA is often accompanied by bending of the DNA. We have studied the ability of C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 to bend its recognition site. A synthetic DNA fragment that contained the C.EcoO109I binding sequence was cloned into the SalI–XbaI site of pBend2, and the electrophoretic mobilities of the DNA fragments generated on restriction digestion were monitored after the binding to C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 (Fig. 9A). The results are shown in Figure 9B. It is clear that although free fragments do not show any intrinsic curving, C.EcoO109I– Hisx6 induces bending in its recognition site. As was found with repressor-operator systems, such as Gal and Lac, and an activator-operator system, such as CRP (22), the degree of electrophoretic retardation of the C.EcoO109I recognition site was highest when the binding site was in the middle and lowest when the binding site was closer to either end of the 141-bp DNA fragment. We have estimated the apparent C.EcoO109I-induced bending angle by following an empirical relationship between the relative electrophoretic mobility retardation caused by bending and the bending angle (23). C.EcoO109I induced an angle of 54 ± 4° in the C.EcoO109I site. As described above, C.PvuII binds to the C box, but no C.PvuII-induced bending has been reported. We have shown here for the first time that a regulatory protein of R-M systems bends the target site.

Figure 9.

Gel electrophoresis of permutated fragments of C.EcoO109I-binding sites. (A) pBend109 constructs and DNA fragments used for assaying. Oligonucleotides with a C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 binding site (shown by open bars), 5′-TCGACAAAAACTAAGTATTCCTTAGTAATT-3′ and 5′-CTAGAATTACTAAGGAATACTTAGTTTTTG-3′, were annealed and then inserted between the XbaI and SalI sites in pBend2 to obtain pBend109. 141-bp DNA fragments were excised from pBend109 with the restriction enzymes indicated above and used for DNA-binding assays. (B) DNA fragments were incubated with C.EcoO109I–Hisx6 and separated on a 8% polyacrylamide gel.

DNA sequences on or near activation of transcription initiation are known to show activator-protein-induced bending. It was suggested that such contortions may be essential for the formation and activity of the DNA–protein transcription initiation complex. It is very likely that DNA bending facilitates additional protein–protein or protein–DNA contacts that involve the activation protein and RNA polymerase. In this study, we demonstrated that: (i) C.EcoO109I acts in trans to stimulate the expression of both the ecoO109IR and ecoO109IC genes; (ii) C.EcoO109I is a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein acting as a homodimer, which recognizes the sequence 5′-CTAAG(N)5CTTAG-3′, located upstream of ecoO109IC; (iii) C.EcoO109I bends its recognition site. The recognition sequence of C.EcoO109I was not found as far as 143 bp upstream of ecoO109IM, and C.EcoO109I did not bind upstream of ecoO109IM. These findings are compatible with the results of deletion analysis and the C.EcoO109I-induced ecoO109IM promoter activity. As there are 10 nt in each chain, at every turn of the helix, the recognition site for C.EcoO109I, CTAAG, faces the same side of the DNA. Therefore, it can be presumed that homodimeric C.EcoO109I interacts with its target DNA, located upstream of its translational start site, from one side of the DNA helix and induces bending, which facilitates the formation of the DNA–protein transcriptional initiation complex at the ecoO109IC promoter. Further analysis of the three-dimensional structures of the C.EcoO109I and C.EcoO109I–DNA complexes will provide us with useful information on interactions such as those between RNA polymerase and C.EcoO109I, subunits of C.EcoO109I, and C.EcoO109I and DNA.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are greatly indebted to Seiichi Yasuda for the gift of pBend2, and to Toshihiko Koga for the gift of pMCL210. This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (A) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mise K. and Nakajima,K. (1985) Restriction endonuclease EcoO109 from Escherichia coli H709c with heptanucleotide recognition site 5′-PuG/GNCCPy-3′. Gene, 36, 363–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kita K., Tsuda,J., Kato,T., Okamoto,K., Yanase,H. and Tanaka,M. (1999) Evidence of horizontal transfer of the EcoO109I restriction-modification gene to Escherichia coli chromosomal DNA. J. Bacteriol., 18, 6822–6827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts R.J. and Macelis,D. (2001) REBASE-restriction enzymes and methylases. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 268–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks J.E., Nathan,P.D., Landry,D., Sznyter,L.A., Waite-Rees,P., Ives,C.L., Moran,L.S., Slatko,B.E. and Benner,J.S. (1991) Characterization of the cloned BamHI restriction modification system: its nucleotide sequence, properties of the methylase, and expression in heterologous hosts. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 841–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tao T., Bourne,J.C. and Blumenthal,R.M. (1991) A family of regulatory genes associated with Type II restriction-modification systems. J. Bacteriol., 173, 1367–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rimseliene R., Vaisvila,R. and Janulaitis,A. (1995) The eco72IC gene specifies a trans-acting factor which influences expression of both DNA methyltransferase and endonuclease from Eco72I restriction-modification system. Gene, 157, 217–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vijesurier R.M., Carlock,L., Blumenthal,R.M. and Dunbar,J.C. (2000) Role and mechanism of action of C·PvuII, a regulatory protein conserved among restriction-modification systems. J. Bacteriol., 182, 477–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kobayashi I. (2001) Behavior of restriction-modification systems as selfish mobile elements and their impact on genome evolution. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 3742–3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakayama Y. and Kobayashi,I. (1998) Restriction-modification gene complexes as selfish entities: role of a regulatory system in their establishment, maintenance, and apoptotic mutual exclusion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 6442–6447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyer H.W. and Roulland-Dussoix,D. (1969) A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol., 41, 459–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yanish-Perron C., Vieiera,J. and Messing,J. (1985) Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene, 33, 103–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kita K., Matsuzaki,K., Hashimoto,T., Yanase,H., Kato,N., Chung,M.C.-M., Kataoka,M. and Shimizu,S. (1996) Cloning of the aldehyde reductase gene from a red yeast, Sporobolomyces salmonicolor, and characterization of the gene and its product. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 62, 2302–2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shine J. and Dalgarno,L. (1974) The 3′-terminal sequence of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA: complementary to nonsense triplets and ribosome binding sites. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 71, 1342–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakano Y., Yoshida,Y., Yamashita,Y. and Koga,T. (1995) Construction of a series of pACYC-derived plasmid vectors. Gene, 162, 157–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zwieb C., Kim,J. and Adhya,S. (1989) DNA bending by negative regulatory proteins: Gal and Lac repressors. Genes Dev., 3, 606–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsudaira P. (1987) Sequence from picomole quantities of proteins electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 10035–10038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kita K., Tsuda,J. and Nishigaki,R. (2001) Characterization and overproduction of EcoO109I methyltransferase. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem., 65, 2512–2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sambrook J., Fritch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 19.Bradford M.M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem., 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laemmli U.K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London), 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alting-Mees M.A. and Short,J.M. (1989) pBluescript II: gene mapping vectors. Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 9494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J., Zwieb,C., Wu,C. and Adhya,S. (1989) Bending of DNA by gene-regulatory proteins: construction and use of a DNA bending vector. Gene, 85, 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson J.F. and Landy,A. (1988) Empirical estimation of protein-induced DNA bending angles: applications to λ site-specific recombination complexes. Nucleic Acids Res., 16, 9687–9705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]