Abstract

Background

People in custody are more likely to die prematurely, especially of violent causes, than similar people not in custody. Some of these deaths may be preventable. In this study we examined causes of death (violent and natural) among people in custody in Ontario. We also compared the causes of deaths in 3 custodial systems (federal penitentiaries, provincial prisons and police cells).

Methods

We examined all available files of coroners' inquests into the deaths of people in custody in federal penitentiaries, provincial prisons and police cells in Ontario from 1990 to 1999. Data collected included age, cause of death, place of death, history of psychiatric illness and history of substance abuse. Causes of death were categorized as violent (accidental poisoning, suicide or homicide) or natural (cancer, cardiovascular disease or “other”). Crude death rates were estimated for male inmate populations in federal and provincial institutions. There were inadequate numbers for women and inadequate denominator estimates for police cells.

Results

A total of 308 inmates died in custody during the study period; data were available for 291 (283 men, 8 women). Of the 283 deaths involving men, over half (168 [59%]) were from violent causes: suicide by strangulation (n = 90), poisoning or toxic effect (n = 48) and homicide (n = 16). Natural causes accounted for 115 (41%) of the deaths among the men, cardiovascular disease being the most common (n = 62 cases) and cancer the second most common (n = 18). Most (137 [48%]) of the deaths among the men occurred in federal institutions; 88 (31%) and 58 (21%) respectively occurred in provincial institutions and police cells. The crude rate of death among male inmates was 420.1 per 100 000 in federal institutions and 211.5 per 100 000 in provincial institutions. Compared with the Canadian male population, male inmates in both federal and provincial institutions had much higher rates of death by poisoning and suicide; the same was true for the rate of death by homicide among male inmates in federal institutions. The rates of death from cardiovascular disease among male inmates in federal and provincial institutions — 102.7 and 51.7 per 100 000 respectively — were also higher than the national average.

Interpretation

Violent causes of death, especially suicide by strangulation and poisoning, predominate among people in custody. Compared with the Canadian male population, male inmates have a higher overall rate of death and a much higher rate of death from violent causes.

In recent years a few reports have looked at the causes of death among people in custody. Most concentrated on the high rates of suicide, especially around the time of arrest and sentencing, although in the 1990s other causes, such as AIDS, made an increasing contribution to overall mortality among inmates.1,2,3,4,5 We undertook this study to examine causes of death of people in custody in Ontario and to compare causes in populations in federal, provincial and police custodial settings.

It is useful to examine these 3 custodial settings separately as well as collectively, because there are differences in the populations and there may be differences in causes of death. For example, in the United States differences in suicide rates have been observed, with rates being significantly higher in short-term institutions (i.e., jails) than in prisons, which usually house individuals with long sentences.6 There has been little analysis of death rates among people in custody in Canada.7 In Ontario, as in most provinces, a coroner's inquest is mandatory for any death of a person in custody, to ensure a public examination of the circumstances leading to the death and to allow comparison of deaths in different settings. Beyond the coroner's inquest, however, there is no formal public scrutiny of in-prison deaths and no publicly reported examination of the causes. The Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, a branch of Statistics Canada, reports the number of deaths of people in custody; however, it has not undertaken a formal study of deaths among incarcerated people.

Our main objective was to classify the causes of all deaths of people in custody in the most populous province in Canada. Our other objectives were to compare the causes of death in federal penitentiaries (housing people sentenced to 2 or more years), provincial prisons (housing people sentenced to less than 2 years and, in some areas, serving as police cells) and police cells (holding people for short stays, usually around the time of arrest) and to compare rates among male inmates in federal and provincial institutions with the rate in the Canadian male population. When available, we examined other relevant factors, such as history of psychiatric illness and substance abuse, in order to determine whether any of the deaths associated with these factors could have been prevented.

Methods

We examined all available files of inquests into the deaths of people in custody (in federal and provincial institutions and in police cells) in Ontario from 1990 to 1999. Deaths occurring inside the institution and after transfer to a medical facility were included.

Deaths of people in all 3 custodial systems are subject to a mandatory coroner's inquest. The coroner presiding at the inquest is assigned by the Office of the Chief Coroner and is independent of the institution where the death occurred. The inquests are conducted with a jury of 5 citizens, who are responsible for making the findings of facts and recommendations. All factors related to the death, including the institutional medical files, psychiatric file and, if relevant, medical records generated outside of the institution, are examined. The records are seized under a coroner's warrant to ensure completeness of the medical evidence. The inquest verdict must answer the questions of who died, when, where, how and by what means the death occurred8 and may include recommendations to prevent avoidable deaths, which are then circulated to appropriate agencies.

We used a standard form to abstract data from the inquest files. Information collected included age, sex, type of institution and place of death (institution v. medical facility). If present, we extracted other relevant information such as history of psychiatric illness or history of substance abuse as well as suicide evaluation. Causes of death were categorized as either violent (presumed accidental poisoning or toxic effect; suicide by hanging; suicide by poisoning or toxic effect; or homicide) or natural (cancer, cardiovascular disease or “other”). The categorization was based on the inquest conclusion and review of the inquest file by 3 of us (W.L.W., J.D. and P.F.). Poisonings (drug overdoses) were assumed to be accidental unless clear evidence of suicidal intent was available.

Categorical variables (death type by institution, death type by substance abuse or psychiatric history, death type by place of death and suicide evaluation) were compared using the χ2 test, and continuous variables (age) were compared using Student's t-test. Rates of death by cause were calculated using whole average populations for federal and provincial inmates. In-custody populations for federal and provincial institutions for 1990–1999 were provided by the Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics.9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 The number of people in police cells was unavailable. Crude mortality rates and 95% confidence intervals were estimated for each cause of death among federal and provincial male inmates; deaths occurring in 1999 were excluded from the analysis of rates because data acquisition was incomplete for that year. Crude mortality rates among similarly aged Canadian men (25–49 years) were used for comparison, and rate ratios were calculated (75% of the federal inmate population falls into this age range; age estimates were unavailable for provincial inmates). Canadian mortality statistics for 1996 were accessed through Health Statistics at a Glance19 available from Health Canada.

Permission for this study was granted by the office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario. The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board at Queen's University, Kingston, Ont.

Results

A total of 308 inmates died from 1990 to 1999. Information from the inquest files was available for 291 deaths (283 men, 8 women). Five of the women died by suicide, and 3 died of natural causes (2 of cardiovascular disease and 1 of meningitis). Five of the women died in federal penitentiaries, 2 in provincial prisons and 1 in a police cell. All further analyses are for the male inmates only. We did not see any significant time trends within the data.

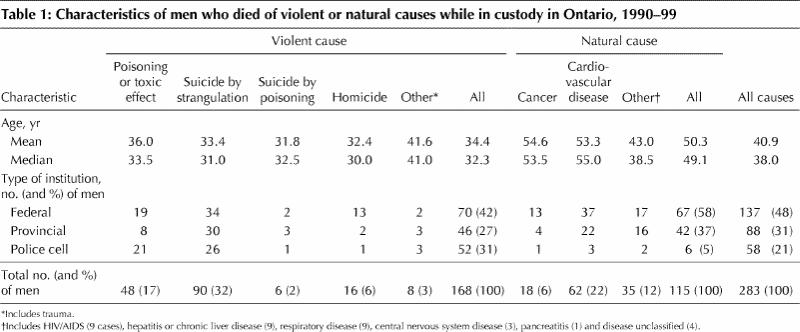

The causes of death of the 283 male inmates are reported in Table 1. The mean age at death was 40.9 years. Overall, 24% of the deaths involved inmates who were less than 30 years old (see online appendix available at www.cmaj.ca). Inmates who died of violent causes were significantly younger than those who died of natural causes (mean 34.4 v. 50.3 years, p < 0.001).

Table 1

Over half (168 [59%]) died of violent causes, the most common being suicide by strangulation (n = 90), poisoning or toxic effect (n = 48) and homicide (n = 16). The majority of suicide deaths were by strangulation (94% [90/96]); the remainder were by poisoning (drug overdose). Those who committed suicide were more likely than others to have a history of psychiatric illness or substance abuse (74% v. 39%) (p < 0.001). Suicide evaluation was documented in the files of 18 (19%) of the 96 inmates who committed suicide, as compared with 1 (0.5%) of the 187 who died of other causes (p < 0.001).

Poisoning accounted for 54 deaths, most of which were due to drug overdose. Six were classified as suicides; the remainder were assumed to be accidental. Deaths by poisoning were more frequent in police cells than in federal or provincial institutions (37% v. 15% and 13% respectively). Over half (55%) of the inmates who died by poisoning had a documented history of substance abuse, as compared with 19% of those who died of other causes (p < 0.01). There were 16 homicides (13 in federal penitentiaries, 2 in provincial prisons and 1 in a police cell).

Natural causes accounted for 115 (41%) of the deaths. Cardiovascular disease was the most common (n = 62) and cancer the next most common cause (n = 18). The majority of deaths from cardiovascular causes were due to ischemic heart disease, and the median age at death was 55 years. A disproportionate number of young individuals died of myocardial infarction (3 were in their 20s, 6 were in their 30s and 11 were in their 40s; the oldest was 79).

Deaths occurred more frequently in federal penitentiaries than in provincial prisons or police cells (137 [48%] v. 88 [31%] and 58 [21%] respectively). Deaths in police cells were more likely to be violent than those in federal or provincial institutions (90% v. 52% and 51% respectively, p < 0.001).

The overall death rate was higher among federal inmates than among provincial inmates (420.1 v. 211.5 per 100 000). The rate for each cause of death, violent (including suicide) and natural, was also higher among federal inmates (Table 2). Rates for prison cells were not calculated because of the lack of an estimate of population size.

Table 2

Interpretation

Premature deaths of people in custody are always tragic. There is a responsibility on the part of the custodial authorities and the public to regularly review causes and rates of death among people in custody and to look for ways to prevent deaths. Studies conducted outside Canada2,5 have shown that people in custody have a higher rate of death than those not in custody. Our findings support this evidence. The rate of death among male inmates in Ontario's federal penitentiaries and provincial prisons was significantly higher than the rate among Canadian men of a similar age distribution (rate among men aged 24–49 years in 1996 was 187.5 per 100 000). The rates for all custodial settings were higher than those in the Canadian male population for all causes except cancer. The most striking difference was with violent deaths, with overdose being 50 and 20 times more common in the federal and provincial inmate populations, respectively, than in the general male population. In addition, the rate of suicide by strangulation was 10 times higher than the national average for federal inmates and 4.5 times higher for provincial inmates. Some of the differences in rates of violent deaths between federal and provincial inmate populations may be explained by the fact that federal institutions house more violent inmates (with longer sentences). However, the federal setting is more stable and more amenable to preventive efforts. US data suggest that we should expect lower suicide rates in long-term (federal) than in short-term (provincial) settings.6 The difference in suicide rates between the federal and provincial inmate populations in our study is worrisome and suggests a lack of preventive effort in federal institutions in Ontario. The rates of death from cardiovascular disease among federal and provincial inmates were 3.5 and 1.7 times, respectively, higher than the rate in the Canadan male population. The deaths were often very premature, with 24% occurring in inmates less than 30 years of age.

Our study was limited by the lack of standard data available in the inquest files. Determination of important factors such as suicide evaluation was often difficult. Calculation of rates among inmates is complicated by high rates of movement both in and out of institutions. For the federal and provincial inmate populations, we used estimates collected by Statistics Canada. For people in police cells, although the raw numbers of certain types of death are worrisome, particularly pertaining to violent deaths, overall rates of these deaths are difficult to estimate given the difficulty in finding reliable estimates of the population size for this group.

Many of the deaths defined in the inquest verdict as being from natural causes seem to have been unavoidable. Exceptions included deaths from chronic liver disease associated with hepatitis and deaths from HIV/AIDS. The low number of deaths from HIV/AIDS differs from the numbers reported in some jurisdictions in the United States1,2 and probably reflects the later rise of HIV infection in Canadian inner cities. The low number of liver-related deaths despite the high rates of hepatitis C in Canadian prisons20 is likely due to the recent nature of the epidemic and the long natural history of the disease process. Of the inmates who died of cardiovascular disease, 9 were in their 20s and 30s. Their low age may relate in part to cocaine, known to cause both acute myocardial infarction and coronary artery disease with chronic use.21 This high burden of cardiovascular deaths requires further scrutiny.

The rate of suicide by strangulation, although similar to the rates reported in other prison studies,3,4,5,7,22,23 is well in excess of the Canadian average. Our estimated rate may be an underestimate because of a 1992 Ontario court ruling that provided that “the required standard of proof is proof to a high degree of probability in order to judge a death a suicide.”24 Indeed, it appears that the Ontario suicide rate has decreased since this ruling.19 Many of the suicides in our study population occurred shortly after arrest and around the time of sentencing, which is a well-documented danger period.5,8,25,26,27,28 Several people in custody had been identified as suicide risks and had killed themselves either while under “suicide watch” or shortly after such supervision had stopped. A study of suicides in federal penitentiaries in Canada concluded that “the vast majority of suicides were in fact not preventable,”7 although other studies suggest that system changes can result in a reduction of suicides.29 Although Correctional Services Canada claims a formal board review (by Correctional Services staff)7 of all suicides by federal inmates, we did not find evidence of this in the inquest files. It is particularly worrisome that suicide rates were higher federally than provincially, whereas one would expect the reverse.

Most of the deaths by poisoning appeared to be accidental and related to overdose by drugs of addiction. Ingestion of drugs before arrest or while out on a pass does occur. Police forces need to be alerted to the dangers of putting intoxicated people in cells and to watch for signs of physical illness. One individual in status epilepticus died after arrest. The arresting officers thought he was resisting arrest and failed to recognize the seizures. Overdose by drugs of addiction is likely to get worse as increasing numbers of people with substance addictions are incarcerated. Some of these deaths could possibly be prevented by the timely application of drug rehabilitation and methadone programs.

In Britain in the early 1800s the death rate among inmates was about 5 times higher that that in the general population.30,31 At the end of the 20th century we have shown an elevated death rate that is twice that of the general population. Violent deaths predominate across institutions, with an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease also evident. Coroners' inquests, conducted for all deaths of people in custody, are the only external and independent means of scrutiny available and the only way of obtaining the information needed to bring about change. Clearly we can do better to reduce the rate of deaths in inmate populations, but it will require more focused effort by custodial authorities and ongoing public scrutiny and concern.

β See related article page 1127

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of Dr. James G. Young, Chief Coroner of Ontario, who made this study possible, and Dr. Sally Ford, Queen's University, for initiating the study.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Dr. Wobeser contributed to the study design and data analysis and drafted the article. Mr. Datema designed the data abstraction form and performed data abstraction and analysis; he also critically revised the paper and gave final approval of the version to be published. Dr. Bechard conceptualized the study and contributed to data acquisition; he also critically revised the paper and gave final approval of the version to be published. Dr. Ford initiated and conceptualized the study and its design, contributed to data acquisition, critically revised the paper and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Wendy L. Wobeser, 3013 Etherington Hall, Queen's University, Kingston ON K7L 3N6; fax 613 533-6825

References

- 1.Amankwaa AA. Causes of death in Florida prisons: the dominance of AIDS. Am J Public Health 1995;85:1710-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Salive ME, Smith GS, Brewer TF. Death in prison: changing mortality patterns among male prisoners in Maryland 1979–1987. Am J Public Health 1990; 80: 1479–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Batten PJ. The descriptive epidemiology of unnatural deaths in Oregon's state institutions. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 1989;10:310-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Spinellis CD, Themeli O. Suicide in Greek prisons: 1977 to 1996. Crisis 1997; 18:152-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Dalton V. Death and dying in prison in Australia: national overview, 1980–98. J Law Med Ethics 1999;27:269-74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Hayes LM, Blaauw E. Prison suicide: a special issue. Crisis 1997;18:146-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Laishes J. Inmate suicides in the correctional service of Canada. Crisis 1997; 18: 157-62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Coroner's Act. RSO 1990, c C37, s 31(1), 31(2). Available: 192.75 .156.68 /DBLaws /Statutes/English/90c37_e.htm (accessed 2002 Sept 18).

- 9.Adult correctional services in Canada 1990-91. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada; 1992.

- 10.Adult correctional services in Canada 1991-92. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada; 1993.

- 11.Adult correctional services in Canada 1992-93. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada; 1994.

- 12.Adult correctional services in Canada 1993-94. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada; 1995.

- 13.Adult correctional services in Canada 1994-95. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada; 1996. Cat no 85-211.

- 14.Adult correctional services in Canada 1995-96. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada;1997. Cat no 85-002-XPE1997004.

- 15.Adult correctional services in Canada 1996-97. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada; 1998. Cat no 85-002-XPE1998003.

- 16.Adult correctional services in Canada 1997-98. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada; 1999. Cat no 85-002-XPE1999004.

- 17.Adult correctional services in Canada 1998-99. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada; 2000. Cat no 85-002-XPE2000003.

- 18.Adult correctional services in Canada 1999-00. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada; 2001. Cat no 85-002-XPE2001005.

- 19.Health statistics at a glance [CD-ROM]. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 1999. Cat no 82F0075XCB.

- 20.Ford PM, Pearson M, Sankar-Mistry P, Stevenson T, Bell D, Austin J. HIV, hepatitis C and risk behaviour in a Canadian medium-security federal penitentiary. Q J Med 2000;93(2):113-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Lange RA, Hillis LD. Cardiovascular complications of cocaine use. N Engl J Med 2001;345:351-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Salive ME, Smith GS, Brewer TF. Suicide mortality in the Maryland State prison system 1979 through 1987. JAMA 1989;262:365-9. [PubMed]

- 23.Report on the work of the prison department 1982. London: Home Office; 1983.

- 24.Beckon v. Young. 1992, 9 O.R. (3d series) 256.

- 25.Marcus P, Alcabes P. Characteristics of suicides by inmates in an urban jail. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1983;44:256-61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Joukamaa M. Prison suicide in Finland. Forensic Sci Int 1997;89:167-74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Backett SA. Suicide in Scottish prisons. Br J Psychiatry 1987;151:218-21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Hurley W. Suicides by prisoners. Med J Aust 1989;151:188-90. [PubMed]

- 29.Cox JF. Morschauser PC. A solution to the problem of jail suicide. Crisis 1997;18(4):178-84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Forbes TR. A mortality record for Coldbath Fields prison, London, in 1795–1829. Bull N Y Acad Med 1977;53:666-70. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Forbes TR. Coroners' inquisitions on the deaths of prisoners in the hulks at Portsmouth, England, in 1817–27. J Hist Med Allied Sci 1978;33:356-66. [DOI] [PubMed]